8 minute read

Speaking Out For Freedom

from Marin May 2023

by 270 Media

Artwork by Laila Rezai

Speaking Out for Freedom

Three local Iranian women use their art to fight discrimination overseas.

BY JASMIN DARZNIK

On a Saturday afternoon in October, in a place that feels, just then, like a kind of country, I join a group of other Iranians in an alley in San Francisco. They haven’t traveled far — physically at least. Most have walked from their homes in the city or driven in for the day from the nearby suburbs to Clarion Alley, in the scruffy, vibrant heart of the Mission.

I shoulder my way past the crowd to where a woman in a blood-red gown stands bound to a chain link fence. She’s crying, I think, only to realize I’m wrong.

She’s singing.

At heart, this performance is meant to mark the recent death of Mahsa Zhina Amini, a young Iranian woman who died while in the custody of Iran’s brutal morality police. What it will become — part of a pulsing network between local women artists and the Bay Area’s Iranian American community — I can’t yet see on that Saturday afternoon.

A lot has happened in the months since that performance in Clarion Alley. Protests in Iran grew and reached a fever-pitch in the last months of 2022. The ensuing brutal government crackdown has taken over five hundred lives, most of them young people and children.

In Marin’s Iranian immigrant community, as in all Iranian immigrant communities around the world, grief and hope now exist in an uneasy mix. Even as the world’s attention has turned elsewhere, we remain besieged by the heartrending images of our homeland streaming on our social media accounts.

If there’s one thing for which I’m grateful, it’s that the events of the last year have introduced me to many remarkable Iranian women artists right here in the San Francisco Bay Area. Amidst so much heartbreak, fear and worry, these women and their art have become a bolstering, empowering force.

The Mirror” by Katayoun Bahrami

I can pinpoint the moment I first became aware of what would eventually take the shape of a global movement. It was the moment I encountered the Instagram page of artist Katayoun Bahrami. Under a grainy photograph of a young woman lying in a hospital bed, she’d written a simple plea: Don’t look away.

Not looking away has long been Bahrami’s ethos as an artist.

After completing her university degree in Tehran, Bahrami lived in Los Angeles before moving with her husband to San Francisco to attend graduate school at California College of the Arts. Her multimedia artworks are riddled with love for the country of her birth.

That profound love for Iran and a desire to amplify its fight for human rights are foremost in Bahrami’s mind when she flicks on her iPhone to connect with an engaged community of followers around the world.

“I have always had this question, ‘Why do women need to cover their hair and their bodies?” Bahrami reflects on her journey to becoming an artist in Iran. "Why do the strictest rules focus on women and their bodies? I have been looking for answers, but little by little, it's become clear that these rules and laws are there for us to obey. Schools and the educational system also have a great role [in insisting women] must remain weak. I always asked this simple question, ‘Why?’”

The performance I attended last fall in the Mission was Bahrami’s brainchild. Presented in collaboration with the Clarion Alley Mural Project and California College of the Art’s Center for the Arts and Public Life in San Francisco, the multimedia event was created to show solidarity with the Iranian protesters. The title, borrowed from exiled activist Masih Alinejad’s book The Wind in My Hair, encapsulates Bahrami’s dreams for the women of Iran.

What struck me as especially powerful about the event was how it brought together not just a diverse range of artists, but also a broad cross-section of Iranian Americans, reminding us how art can create and hold a space for a community splintered by grief.

Mobina Nouri

Mobina Nouri cuts an unforgettable figure. A multidisciplinary artist based in San Francisco, Nouri’s practice reflects her personal history as an Iranian immigrant woman. She received her BA in performance art and MA in art and design from Tehran University of Art in Iran and her PhD in creativity from City University of London. Working across a variety of media, she mines Iranian traditions of music and storytelling, often turning to philosophy and mysticism to probe the contemporary Iranian moment.

When Mahsa Amini died last summer, Nouri’s work came to a sudden standstill. She felt her then-existing practice, which drew on traditional Persian calligraphy and iconography to tell the stories of immigrant women, felt inadequate. Eventually, she turned to AI-generated art, creating digital renderings that weave together the beauty of Iranian culture and the violence so long inflicted on its women. They’re hard images to look at — to which Nouri replies that beholding such violence is nothing next to living it.

In the wake of Mahsa Amini’s death, chopped hair and discarded hijabs quickly became worldwide symbols for Iranian women’s liberation. Nouri seized on this imagery.

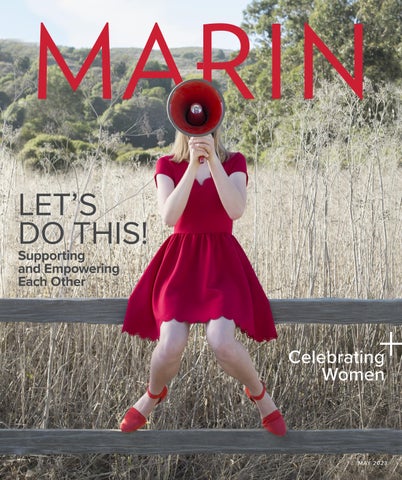

As part of her performance at Clarion Alley, she sectioned off locks from her long, dark hair. Each bore the picture and name of an imprisoned protester. She attached dozens of pairs of tiny scissors to her red gown and stood with strands of her long black hair tied to a gate. In a stirring gesture, she then invited people to cut her hair and keep the pictures as sobering reminders of the individuals’ fates.

“Art creates reality for all of us," says Nouri. "This awareness empowers women and society, and more importantly, the hope and the future that we are creating collectively for girls and females around the world.”

As the crackdown against protestors in Iran continues, Nouri’s performance, which has since been repeated at the Legion of Honor, grows more poignant.

shaghayegh cyrous Women. Life. Freedom. It’s the slogan that has defined the movement for human rights in the wake of Mahsa Amini’s death. Thanks to one Iranian-American woman, this past autumn these three words were emblazoned on the San Francisco skyline.

On a clear night, the crown of Salesforce Tower is impossible to miss. Illuminated by 11,000 LED lights, the top eight floors of the tower are the site of "Day for Night," a stunning public light sculpture created by artist Jim Campbell and launched in 2018.

When local Iranian-American artist Shaghayegh Cyrous collaborated with Campbell last fall, Salesforce Tower was transformed into a beacon of human rights.

Cyrous dedicated “When the Sun Rotates” to all dancers who have been arrested in Iran, as dancing in public is illegal there. In the piece, the sun represents the light that dances and rises throughout the night, beating back darkness.

The Farsi writing on the tower read , “In Honor of Iranian Women,” to honor women of Iran’s continued fighting in April 2022, and was projected again right at the beginning of the movement in September 2022 in memory of Mahsa Amini, as well as the Woman, Life, Freedom movement in Iran.

“It has been tough being away from Iran for the past 10 years, but it has been empowering to witness the movement by women is continuing in Iran and the world is finally listening," says Cyrous. "I would do anything to use my privilege of freedom of speech to amplify voices of women, and all Iranians who keep getting muted, but never give up.”

Giving up is not an option anymore — not for Cyrous and not for Katayoun Bahrami or Mobina Nouri. They’re too busy collapsing time and distance, bringing Iran into bright relief for the world.

In her own way, each artist is recasting the image of one of the most demonized countries in the world and opening a lens onto how Iranian women actually live today. Their work is also about stepping away from stereotypes that have defined Iranian women for too long — women who seem impossibly foreign and who must be forever pitied.

One painting, film and performance at a time, they’re offering a new story about what Iran and its women are and might yet become.