13 minute read

5.1 Introduction

98

z0 ε μ

Advertisement

μt μeff ρ

σk

Aerodynamic roughness length [m] Turbulent energy dissipation rate Dynamic viscosity Turbulent viscosity Effective viscosity Density Turbulent constant, 1.0 σε Turbulent constant, 1.3 Cε1, Turbulent constant, 1.44 Cε2 Turbulent constant, 1.92 Cμ, Turbulent constant, 0.09

gi Gravitational acceleration in the i axis

I y*

z0 k Average turbulence intensity Dimensionless wall distance Aerodynamic roughness length [m] Turbulent kinetic energy

κ

von Karman constant

L Turbulence length scale [m]

p Pressure

P

Turbulent production term ui Velocity component in the i axis ABL Atmospheric boundary layer BCT Bank of China Tower BIM Building information modeling CIM City information modeling CKC Cheung Kong Center CTBUH Council on Tall Buildings and Urban Habitat ES Exchange Square ET Edinburgh Tower FSP Four Seasons Place GT Gloucester Tower HOMER Hybrid Optimization Model for Electric Renewables IFC International Finance Centre JH Jardine House OIFC One International Finance Centre RANS Reynolds-averaged Navier–Stokes SMO Survey and Mapping Office TI Turbulence intensity WPD Wind power density WRA Wind resource assessment Chapter 5

Wind power, and associated harnessing technologies, have become an imperative part of the renewable energy industry and the move towards a sustainable economy [4, 157-159]. Power that can be generated by harvesting wind within urban environments (hereafter, ‘urban wind energy’) is a promising energy source. However, it is currently not exploited because the wind speed distributions around buildings are highly complicated with great turbulence intensities (TIs) [8, 9, 160], and no studies have attempted to determine the optimal locations for wind turbines in such environments. Severe turbulence can make it very difficult to capture good-quality wind.

Urban wind energy potential for a realistic high-rise urban area 99

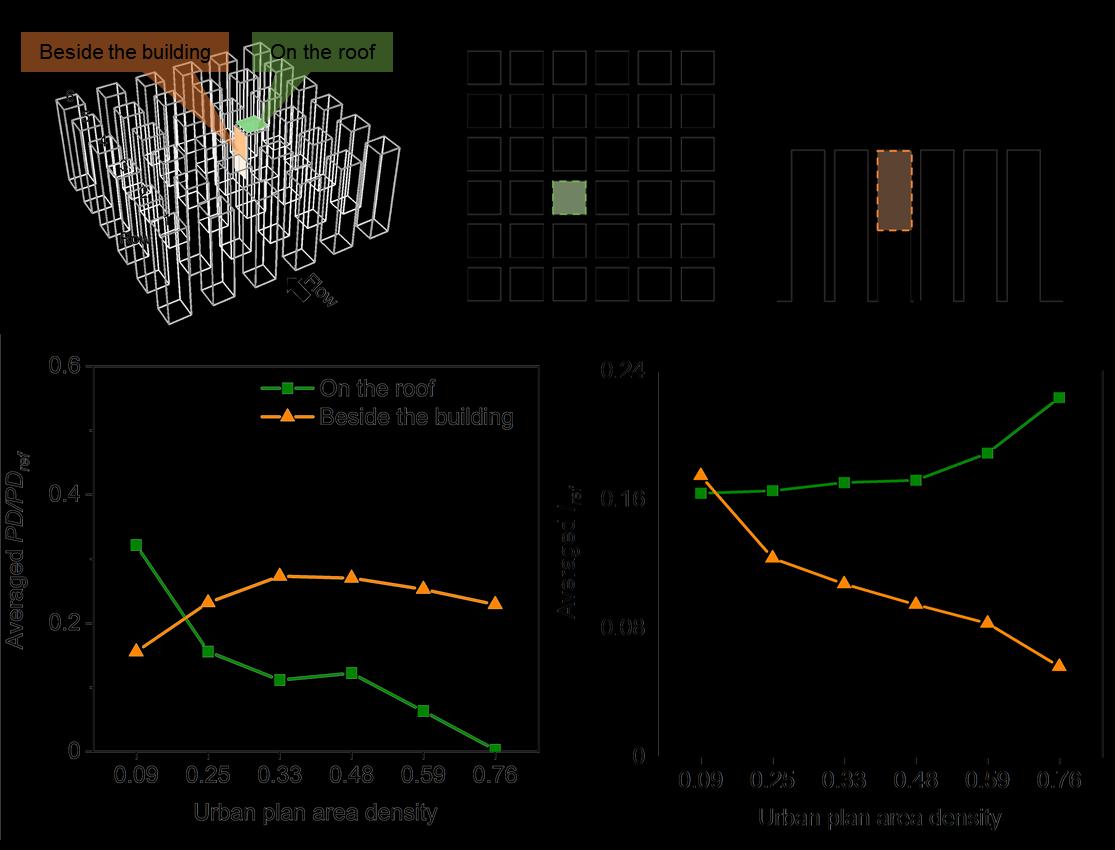

However, at the same time, in complex, dense urban areas, disturbed flows around high-rise buildings tend to be locally accelerated, and in theory such areas of high airflow speeds could be exploited for power extraction. Indeed, buildings themselves can be purposely designed to augment such high-speed wind flow. Therefore, it is becoming increasingly necessary to be able to pinpoint suitable installation sites for deploying wind turbines in urban areas. Assessments to this end should consider the urban terrain in conjunction with local wind characteristics around buildings.

Some general guidelines related to wind turbine deployment on buildings have been published, which include installing each turbine as high as possible [161], as close as possible to the center of the rooftop [161] or the sidewall between two adjacent buildings [78], and a sufficient distance away from other turbines [161], and the implementation of tall building-integrated wind turbines [150]. However, these conventional guidelines were established without considering the interference of surrounding structures and the airflow over an entire site. In our recent paper [17], the effects of adjoining constructions on the wind environment around the subject buildings may be important in resolving prospective mounting sites in convoluted urban terrains. It is also advantageous to determine the optimized hub height of wind turbine installation around the buildings for realizing better wind power capacity.

There are a variety of methods for estimating the wind resources at a site, including the use of meteorological data [162-166], field measurements for measure-correlate-predict (MCP) methods [51, 167-169] or Sound Detection and Ranging (SODAR) [170], and modeled resource data [17, 171]. In order to appraise the available wind energy for power generation from micrometeorological data, Gunturu et al. [172] inspected the shape parameters for the Weibull velocity distribution of wind across the United States to identify the locations with high power densities; however, the Weibull model is merely an approximation of the wind speed, whose value is usually small, and thus the results of wind power density (WPD) cannot be accurate. Khan et al. [173] used Weibull analyses and the Hybrid Optimization Model for Electric Renewables (HOMER) to attain applicable hybrid energy systems in Newfoundland. Despite that, HOMER simulates a list of current technologies as available tools; it requires very detailed meteorological data and time to analyze specific energy sources. As mentioned above, a number of overly simplified methods via local micrometeorology data, the Weibull analysis or HOMER were conducted to evaluate wind resources, which cannot be utilized to establish the prospective sites for turbine installation. Normally, the long-term meteorological wind data are few or don’t exist at 50+ meters above the ground level for a particular area referred to as observed data sets. Even the wind data from the nearest weather stations or locale airports can be still far away from the target site, which may produce significant errors in wind energy estimation in complex terrains. Thus, it requires that the field measurement must be recent enough in order to describe better the current wind conditions [174]. Ideally, long time field measurements at the target site are considered the most reliable but can be costly and time consuming, taking up to over a 10year period [174, 175] or a least for one year [176] to collect data. One alternative way to low-cost wind resource assessment is to conduct short-term measurements at a prespecified location with MCP approaches for at least three months [177-179]. The gathered short-term data can be correlated with these measurements with an overlapping time series of another site utilizing the statistical models. Veeramachaneni et al. [177] collected the wind data as minimal data as possible for wind resource assessment. The minimal data of 3 months is still available to attain the good capability of accurate estimations of wind power. Weekes and Tomlin [178] carried out 3 months on-site wind measurements combined with MCP-predicted wind resources and accurately predicted the available wind power density at three viable sites. Bechrakis et al. [179] conducted the study offering a reliable indication of the annual wind energy potential of a target area using only short time period concurrent measurements (1-month from target site and 2-month from

100 Chapter 5

reference site) to quickly and satisfactorily estimate the energy yield. However, none of the aforementioned results employed any topographical detail in wind energy assessments. Considering the serious deficiencies of those simplified methods, the influences of realistic urban configuration and arrangement on the fields of wind power density and turbulence level in a specific area is therefore an imperative determinant of the most favorable locations and installation heights of wind turbines. In summary, all methods currently available for wind resource assessment (WRA) face major hurdles in practical application. The main challenges are summarized below [180]: a) Since wind is a type of weather phenomena, there is inherent uncertainty in forecasting the long-term wind resource. b) It is lack of high-quality, long-term meteorological measurements at enough height in areas of particular interest. c) For the long-standing average records, such as on a monthly or yearly basis, WRA can underestimate the WPD because higher speed records that contribute the most to calculated wind power densities tend to be smoothed out. d) Wind speeds can be affected by the terrain and building shapes, leading to an approximate deviation of ±10% between the measurements and actual turbine installation sites. e) WRAs require sufficient, critical data on wind velocity distributions, wind direction and turbulence intensity, to resolve or adjust the installation site and height. f) The accuracy, location, and even orientation of measurement instruments can affect wind measurement data and validation results.

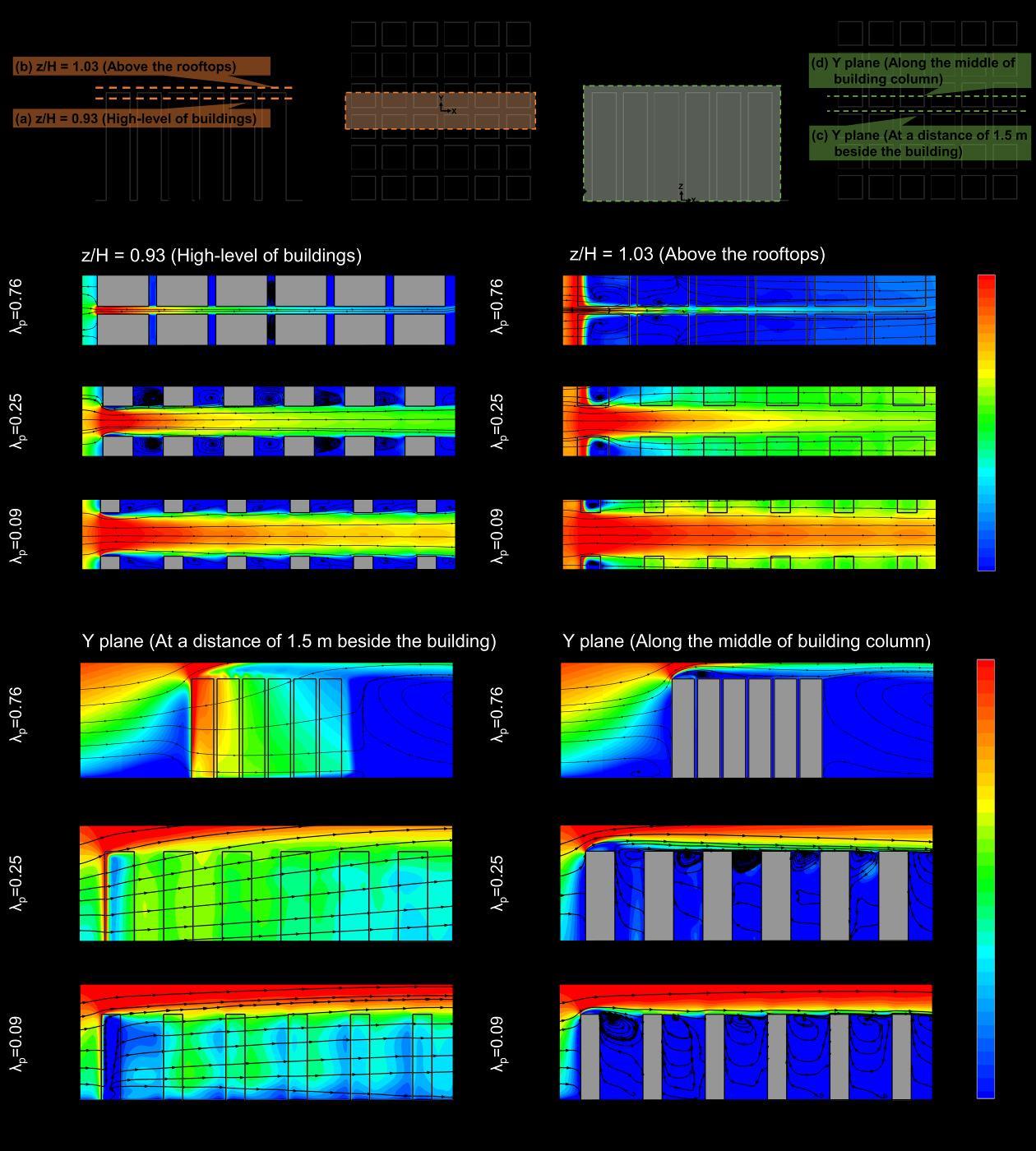

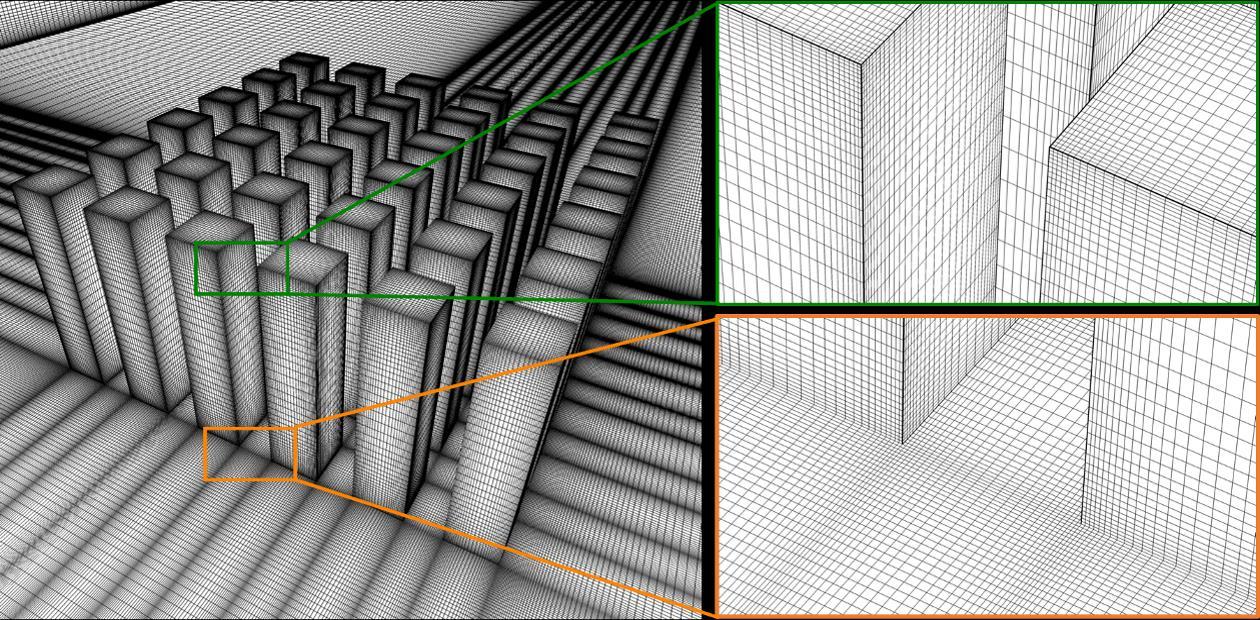

The task of modeling urban wind motion is difficult in essence. Each urban environment with particular surface roughness describing the height change of building blocks has its local characteristics, and this affects the airflow circulation in and around it and thus the harvestable wind resources. Computer modeling provides large-scale numerical meteorological models produced to extrapolate wind states at a specified site from the chronological data. It validates the detailed wind field at the site via a combination of on-site wind measurements coupled with computer models from long-lasting weather data. Without collecting the microclimate data from the CFD-based analysis for the definite locations, it may cause serious miscalculations to assess the wind power from the weather conditions [181, 182]. CFD simulations can be used to optimize turbine orientation, building designs, and installation locations. In addition, it can be incorporated into models of airflow across urban open spaces, which is known as building information modeling (BIM) or city information modeling (CIM) at a city scale. In earlier researches, CFD simulations have been shown to be useful for obtaining detailed urban characteristics employing fine-scale topography of computational models. Besides, to reflect the actual complexity of the problem, field measurements are needed to validate against the results of wind tunnel experiment and CFD simulation for urban environments [183]. However, with the major attention on evaluating urban wind power, the studies of examining the CFD models by field measurements [71, 77] are rarer than those by wind tunnel experiments [36, 37, 64-66, 75, 79, 109].

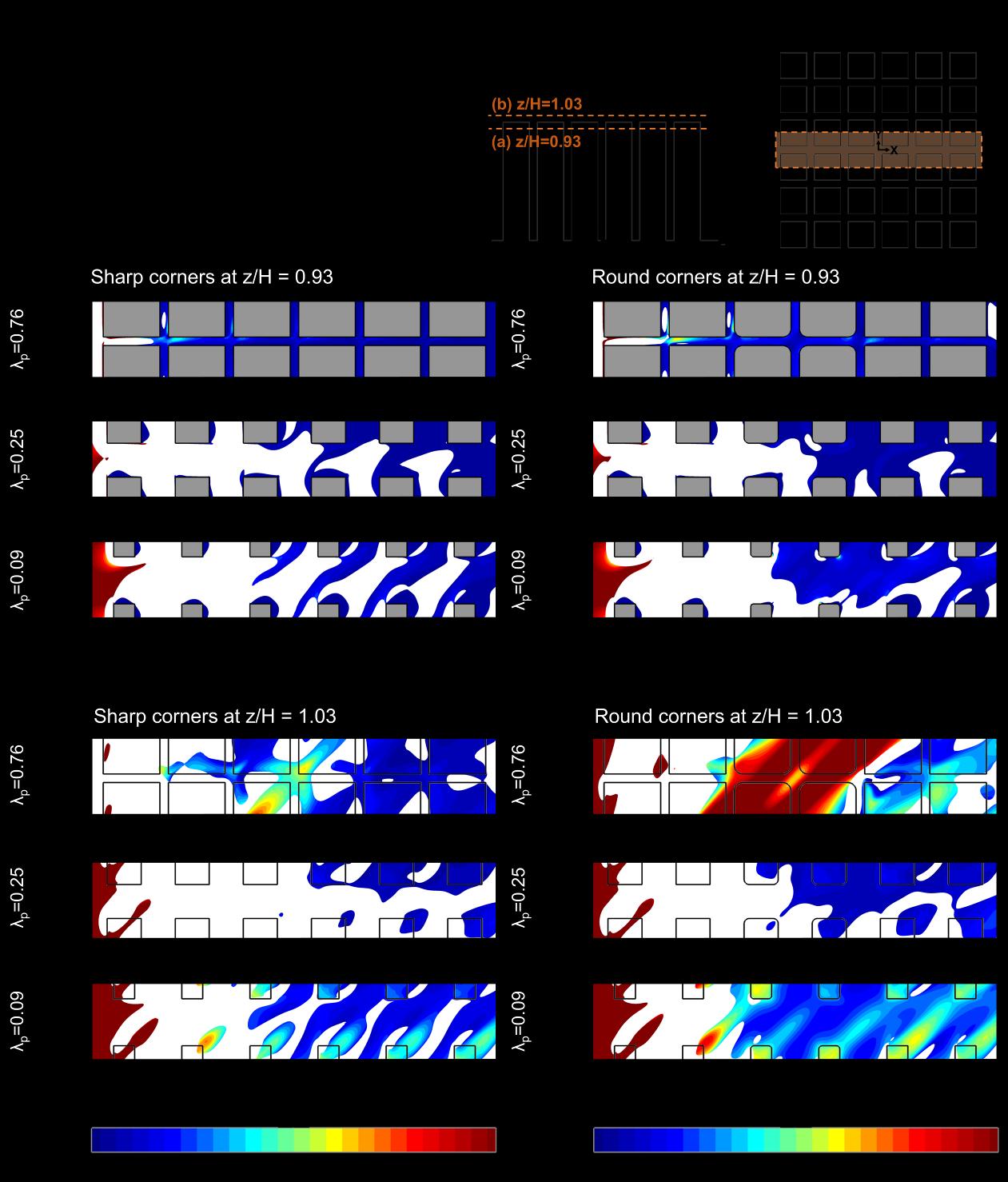

The wind features around buildings can be substantially influenced by complicated urban morphologies. Accordingly, prior studies have struggled to produce realistic results [75]. Some studies have assessed wind power using wind power with simple generic architect models, thereby neglecting the complex structures of an urban city, and have analyzed potential wind power based on interactions between airflow and a single building [8, 64, 65, 70, 72, 184, 185] or several parallel buildings [66, 69, 78, 109] without considering the surrounding structures. Other studies have modeled cities with rectangular buildings of the same height [36, 37, 79] or with different types of roof shapes[36, 37, 79] and pitch angles [75, 185]. Some studies have explored the influence of generic buildings with various shapes on the wind power production [69, 70,

Urban wind energy potential for a realistic high-rise urban area 101

186]. Few studies have addressed wind estimations in actual urban areas. Those that have are summarized in Table 5.1. Dilimulati et al. [53] modeled a study site as a 500 m radius open area surrounding a commercial region to probe the performance of various types of various wind turbine designs and quantify the urban wind resources. Wang et al. [187] performed CFD simulations to evaluate the utilization of wind energy with turbines mounted on the roof on a campus. Wang et al. [188] compared and analyzed the wind resource characteristics of 7 varied urban tissues to estimate the wind power potential. Zhou et al. [189] simulated the wind across identified buildings from an urban residential community to explore the available wind energy resource. Yang et al. [17] performed the on-site full-scale measurements coupled with CFD simulations to resolve the power densities and turbulence intensities of the integrated technology complex building (ITCB) with a surrounding area of 500 m radius to evaluate the wind energy. Chaudhry et al. [69] analyzed the wind distribution around the Bahrain Trade Centre, the first wind turbines integrated skyscraper in the world, to determine the power generation of this highrise building. Lu et al. [70] applied the concentration effects to enhance wind energy at different heights of a high-rise building on campus. Taking several representative urban district categories into account, Beller [190] examined the inherent airflow phenomena around obstacles to inspect wind energy potential. Kalmikov et al. [191] carried out the advanced simulation with the complicated urban terrain to appraise the actual wind resources on campus. For the aforementioned CFD studies of wind resource assessment in realistic urban areas, it is common to find the situations lacking to include the multiple effects together. For instance, most of the publications present the wind resource assessment, but: 1) simply discuss the wind speed without considering the effect of the turbulence intensity; 2) only estimate wind power of several simplified buildings and hardly contemplate the associated surrounding area; 3) merely perform simulations without any measurement to validate the accuracy of CFD predictions. Hence, this study considers the surrounding area with a radius of 1 km, including all details of actual highrise buildings; accordingly, the wind flow can be modeled with detailed topography and roughness. We also conduct more comprehensive on-site measurements in an actual urban environment to validate our CFD model, leading to reasonable WRAs for accurate estimates of annual energy production.

Table 5.1. Literature review of computational studies carried on wind resource assessment in realistic urban layouts

Publication Ref. Configuration Range of surrounding area Turbulence modeling Validation

This study 3D / Realistic high-rise urban area Radius of 1000m

Dilimulati et al. (2018) [53] 3D/ A commercial area Radius of 500m Steady RANS/ RLZ Steady RANS/ SST & RKE Field

Wind tunnel

Wang et al. (2018) Wang et al. (2018) Zhou et al. (2017)

Soebiyan et al. (2017) [187 ] [188 ] [189 ]

[192 ] 3D/ Single simply building from a campus None Steady RANS/ RKE Field

3D/ 7 different urban tissues Radius of 800m No Field

3D/ Residential areas with the designed building shape in sample building(s) 3D/ A Campus consists of two buildings 1000m* 1000m No No

25,000 m2 Steady RANS/ SKE No

102 Chapter 5

Yang et al. (2016) Chaudhry et al. (2015) Lu et al. (2014) Beller (2011) Kalmikov et al. (2010) [17] 3D/ A campus with surrounding area Radius of 500m

Steady RANS/ RKE [77] 3D/ Two high-rise towers None Steady RANS/ SKE Field

No

[70] 3D/ Two simplified buildings from studied campus

[190 ] 3D/ Building configurations from 4 different studied sites

[191 ] 3D/ A campus with idealized smoothed buildings 200m*500m Steady RANS/ RNG No

None Steady RANS Field

None Steady RANS Field

SKE= Standard k-ɛ model; RNG= Renormalization group k-ɛ model; RLZ= Realizable k-ɛ model; SST =Shear Stress Transport k-ω model.

Wind turbines cannot be installed effectively without knowing the details of local wind characteristics [53], and previous studies on generic buildings or over-simplified urban areas may produce unreliable results due to the neglect of realistic situations of surrounding buildings. This paper aims to illustrate an improved method for evaluating wind resources in highly urbanized areas. We conducted the CFD simulations of the wind over high-rise buildings in Central, Hong Kong, to identify the places with higher wind speeds and lower turbulence levels, which are greatly affected by the intricate topography of surrounding high-rise buildings and urban layouts. The turbulent flow characteristics and wind speed distributions can be quite different from the free stream in the proximity of high-rise buildings. Accordingly, there is a need to verify CFD calculations of detailed flow characteristics with the on-site measured data. The wind measurement and CFD simulation results around the subject buildings can provide a much more accurate and detailed wind environment data, including the airflow velocity and turbulence distributions, to facilitate the feasibility analysis for installation of wind turbines on the rooftops of high-rise buildings in urbanized areas. This study conducts CFD validations via the simulations of two cases in the summertime and wintertime. The predicted wind flow velocity, direction, and turbulence intensity (TI) are validated with the on-site wind measurement results using ultrasonic anemometers and a heat ball probe. The WRA is primarily based on the CFD results by the yearly wind data. Considering the prevailing wind past the buildings in the highly urbanized areas to exploit the available wind resources, the distributions of WPD and TI are assessed at the favored apposite locations for turbine installation. This investigation also fully analyzes the impacts of the building geometry, the roof shape, and upstream obstacles of a single high-rise buildings, the gap distance between integrated building complexes and the deep street canyon of parallel high-rise buildings on wind power characteristics. The outcomes of local WRA can be used to suggest the probable mounting sites and orientations for the wind power development and maximum use of urban wind energy in highly urbanized areas. Various market and technical factors, consisting of the government support policy, environmental effect/urban planning, market demand condition, financial mechanism, geographical influence and wind turbine efficiency, can significantly affect the long-term development and competitiveness of urban wind power applications. Without analyzing the aforementioned factors, this investigation mainly applied the detailed topography and boundary conditions of an urban microenvironment to improve the accuracy of estimating wind power potential in realistic highly urbanized areas to put forward for the sustainable development of future essential policy recommendations.

The remainder of the paper is divided into six sections. Previous studies of wind energy resources in Hong Kong are described in Section 5.2., as are the details of local meteorological data of the study site. Section 5.3. introduces the on-site wind measurements utilized for CFD validation. Section 5.4. reports the features of a complex urban topography are considered in the