Design Anthology UG6

Architecture BSc (ARB/RIBA Part 1)

Compiled from Bartlett Summer Show Books

Architecture BSc (ARB/RIBA Part 1)

Compiled from Bartlett Summer Show Books

At The Bartlett School of Architecture, we have been publishing annual exhibition catalogues for each of our design-based programmes for more than a decade. These catalogues, amounting to thousands of pages, illustrate the best of our students’ extraordinary work. Our Design Anthology series brings together the annual catalogue pages for each of our renowned units, clusters, and labs, to give an overview of how their practice and research has evolved.

Throughout this time some teaching partnerships have remained constant, others have changed. Students have also progressed from one programme to another. Nevertheless, the way in which design is taught and explored at The Bartlett School of Architecture is in our DNA. Now with almost 50 units, clusters and labs in the school across our programmes, the Design Anthology series shows how we define, progress and reinvent our agendas and themes from year to year.

2024 Registration

Stefan Lengen, Ben Spong

2023 Calibrating

Stefan Lengen, Ben Spong

2022 The Gravel is the Place for Me

Stefan Lengen, Jane Wong

2020 Material Cultures

Paloma Gormley, Summer Islam

2019 Tilt-Shift: Long Views Across the Edo

Farlie Reynolds, Paolo Zaide

2018 Gravesbury: 4IR

Charlotte Reynolds, Paolo Zaide

2017 Drifting Cityscapes

Tim Norman, Paolo Zaide

2016 Indian Nose Reconstruction

Christine Hawley, Paolo Zaide

2015 Hong Kong Reconsidered

Christine Hawley, Paolo Zaide

2014 Edge: Fragile Landscapes

Christine Hawley, Paolo Zaide

2013 The Peckham Experiment

Christine Hawley, Paolo Zaide

2012 Schools for Tomorrowland

Sabine Storp, Paolo Zaide

2011 Housing 192060

Christine Hawley, Paolo Zaide

2010 Foods and Excess

Christine Hawley, Paolo Zaide

2009 Altered States

Liam Young, Paolo Zaide

2008 Landscape

Ben Addy, Stuart Piercy

2007

Ben Addy, Stuart Piercy

2006 Ebb + Flow

Ben Addy, Stuart Piercy

2005 Trigger Mechanisms

Bernd Felsinger, Stuart Piercy

Stefan Lengen, Ben Spong

UG6 is fascinated by the reciprocity between methods of architectural design and production and the worlds they give rise to. By engaging the poetic with the practical, and the conceptual with the constructed, we seek to discover a wider range of spatial, material and temporal possibilities for architecture that are more attuned to the sensibilities of our ecological condition.

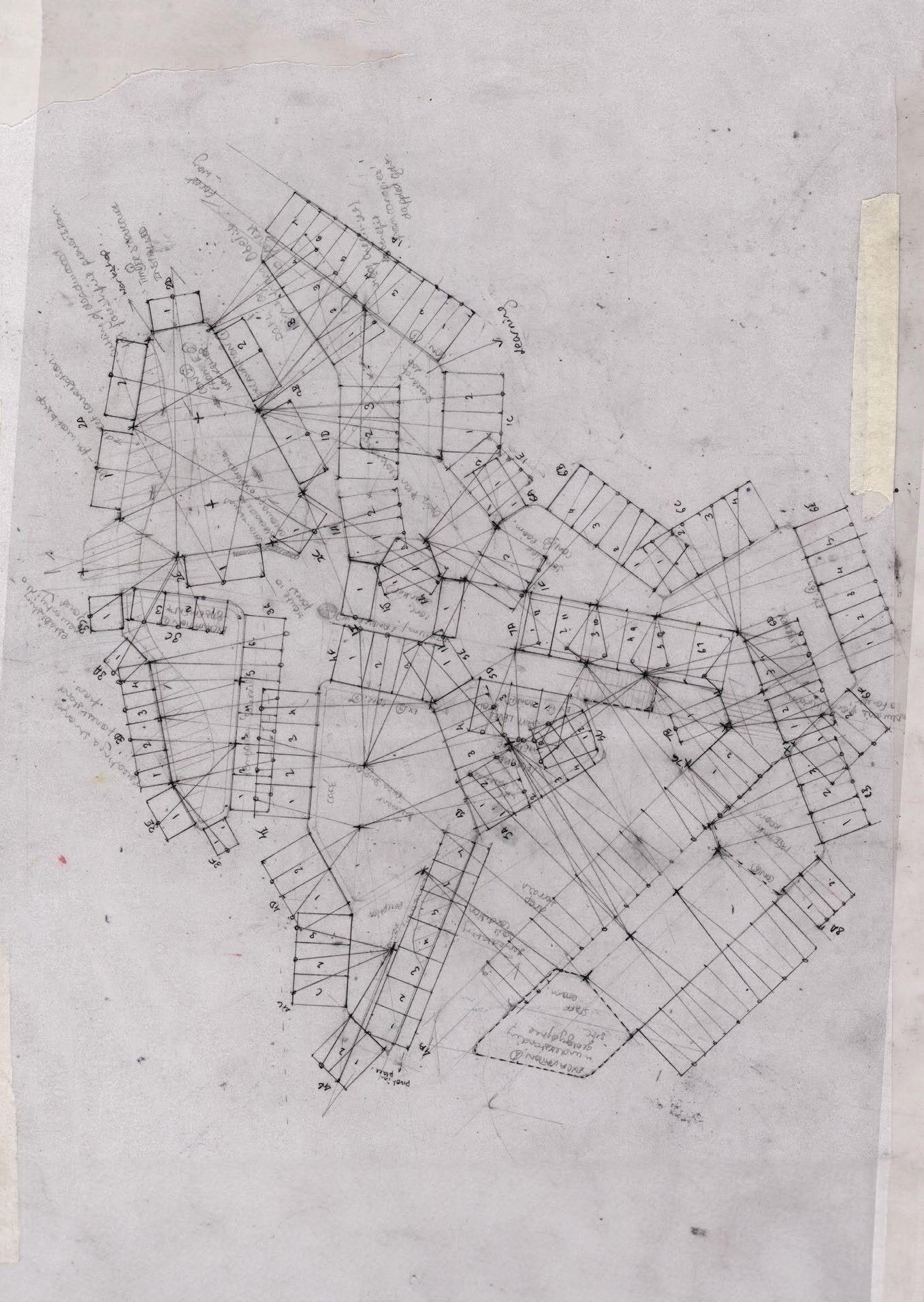

Our theme for the year was ‘Registration’, a process for determining the relativity of things. Consider an artist who performs a form of geometric registration by marking the surface of their drawing to determine the spatial difference between features in a landscape. This type of registration attempts to offer certainty over an otherwise changing landscape by figuratively clamping it in place. The impact of this reductive form of registration is felt across architectural production, from the site survey through the design process to the placement of materials in the form of a building and its eventual occupation.

While recognising this utility, this year UG6 was captivated by the idea of registration as a form of enquiry that can draw out worlds rather than impose order upon them. By recognising the unique position the register holds – it is explicitly between things – we developed tools, methods and processes that acted as intermediaries between us and the agencies, environments and materials we wished to engage. In this light, the act of registration doesn’t cull differences, but provides the ground for differences to play out, which in turn holds the potential to produce radically new ways of practising, building and occupying architecture.

At the beginning we acted on hunches to build digital and physical instruments that speculatively probed at our site for the year, the Epping Forest District in Essex. As the work progressed these were translated, transformed and extended into sensitive building proposals that were acutely aware of the ecology in which they are situated and participate.

Our field trip this year was to Copenhagen and Aarhus where we learned about the intersections of our research with the Aarhus School of Architecture, Royal Danish Academy (CITA and the Architecture and Extreme Environments programme) and the Danish architecture practices Vandkunsten and pihlmann architects.

Year 2

Sora Aoki, Jacob Dumon, Yang Huang, Min (Kristine) Huang, Jiahe (Ryan) Shao

Year 3

Thomas Butterworth, Diego Carreras, Pacharamon (Myla) Danwachira, Rhiannon Howes, Aryan Kaul, Laura Noble, Sean Ow, Eden Robertson, Jerzy (George) Szczerba, Shuheng Wang, Zhi Qi (Tina) Wu, Peiyan Zou

Technical tutors and consultants: Ivan Chan, Alex Fox, James Della Valle, Nicolas Pauwels, Lynn Qian, Eoin Shaw

Critics: Abigail Ashton, Mark Bagguley, Laurence Blackwell-Thale, William Victor Camilleri, AnaMaria Cazan, Nat Chard, Peter Cook, James Della Valle, Florence Hemmings, Joe Johnson, Nikoletta Karastathi, Kyriakos Katsaros, Chee-Kit Lai, Isac Leung, Nicolas Pauwels, Lynn Qian, Farlie Reynolds, Luke Ryuichi Saito Koper, Eoin Shaw, Colin Smith, Sarah Stevens, Kate Taylor, William Tindall

Special thanks to B-made, Alicia Lazzaroni and Chris Thurlbourne (Aarhus School of Architecture), David Garcia and Tom Svilans (Royal Danish Academy), Thais Espersen and Søren Nielsen (Vandkunsten Architects), Søren Pihlmann and Isabella Priddle (pihlmann architects)

6.1, 6.17 Aryan Kaul, Y3 ‘Hyper-localising the Tilt’. The project explores the production and demonstration of cast-in-ground, in-situ tilt-up architectural components, using materials that are hyper-local to the context. The architecture is established for a perpetual feedback loop between silvicultural research and intervention, bespoke component fabrication and spatial assemblies.

6.2, 6.13 Shuheng Wang, Y3 ‘Time Magnificents’. The term ‘architectural scale’ assumes that a building will inevitably impact its site. This project re-examines the interaction between a building and its surroundings in an ‘aggressive’ manner. Wind, a significant natural phenomenon, serves as a crucial medium for this project to achieve its goal of interacting with nature. It also provides the means of the programme: a geological research centre.

6.3–6.4 Zhi Qi (Tina) Wu, Y3 ‘The Stretch Lab’. The project, situated in the outer ring of Epping Forest, London, explores the potential of applying inflatable soft robotics technologies in architecture to enhance the relationship between the body and architecture. Given that the building serves as a physiotherapy rehabilitation centre, the theme of recovery is central. In the context of recovery and the body, inflatable soft robots are integrated into the architecture as soft machines, actively participating in the recovery process.

6.5, 6.8 Laura Noble, Y3 ‘Can You See the Birdsong?’. Sited in Epping Forest, this project embeds a postoperation rehabilitation centre organised around the concept of sonic spatiality for the benefits of recovery. Using form (from diffusive to directive) and materiality (from absorptive to reflective) to create a variety of sonic conditions, the project amplifies the soundscape of the forest.

6.6 Yang Huang, Y2 ‘Vocal Library’. This project is located in Loughton, Essex, in a disused parking lot. The project proposes a sonically charged library with several functions to improve the relationship between different generation groups in the local area.

6.7, 6.9 Pacharamon (Myla) Danwachira, Y3

‘Choreography of the Rewilding’. Situated on Chingford Plain, the project attempts to blur the boundary between the community and the woodland, proposing an invitation to reimagine the cohabitation of cattle, forest and humans. Drawing on the lost ancient tradition of Epping Forest and its 21st-century ecological consequences, the project rewilds the ecological mosaic while reviving its ancient traditions.

6.10–6.12 Peiyan Zou, Y3 ‘Digital Penumbra’. The project was designed through the ‘inappropriate’ use of 3D scanning, iterating the design based on voids and glitches in the scans. The indeterminate elements of everyday life captured in the scans are where the designer’s authorship is integrated with the hyper-precise scanner. This approach synthesises perception, memory and time, proposing an unprecedented architectural conservation technique in response to the consultation between the residents of Waltham Abbey and the council over the refurbishment of the area.

6.14 Min (Kristine) Huang, Y2 ‘The Shape of Light’. Situated on a lakeside plain within Epping Forest, the sculpture museum celebrates Isamu Noguchi’s legacy by exploring the interplay of light and sculpture. Inspired by the philosophy of ‘giving shapes to light’, its architecture allows light to emanate from and shape spaces, turning them into sculptural forms.

6.15 Thomas Butterworth, Y3 ‘The Epping Commons: A Centre for Regenerative Deliberation’. The Epping Commons is an exploration of the architectural mediation of people, politics and time. The project proposes design strategies that anticipate change over time, establishing the cyclical ritual upkeep of the architecture through collective participation.

It uses hyperlocal materials, contributing to the regeneration of the surrounding natural environments.

6.16 Jacob Dumon, Y2 ‘Under the Knife’. This project explores the role of boundaries, examining their different scales within a plastic surgery clinic. Understanding the uncertain boundary of a tree burl has led to a developed interest in how manipulated bodily boundaries can extend to and alter experienced architecture.

6.18 Rhiannon Howes, Y3 ‘Broaching Boundaries: Reframing the Stewardship of Allhallows Marshes’. The project serves as a settlement on a tidal Allhallows Marshes, redefining boundaries historically shaped by industry and perception, negotiating and curating the site’s inherent liminality. Ground conditions inform form, while function serves stewardship, as herders, thatchers and builders manage the marshy landscape of their surroundings.

6.19 Eden Robertson, Y3 ‘Vanitas: Women’s Health Centre’. Set adjacent to the border of Epping Forest, this project investigates the extent to which architecture can be used as a medical tool for healing and caring for women’s bodies. It activates the art-historical term ‘vanitas’ to explore women’s symbolic relationship with morality and architecture’s discomfort with degradation.

6.20 Jiahe (Ryan) Shao, Y2 ‘A Momentary Retreat at Connaught Water’. This project stemmed from an interest in the space that drawing occupies during its creation. The spatiality of drawing was investigated through a drawing board charged with the topography and water movement on site, interpreted intuitively by the drawing hand. This established a ‘momentary retreat’ that hosts dialogues between visitors and the landscape.

6.21 Sora Aoki, Y2 ‘From the Ground Up’. Situated on the edge of Walthamstow Wetlands, this project serves as an urban extension of Epping Forest, accommodating a community of artists and their sculptural creations. An earthy architecture, camouflaged in the manipulated landscape, evokes a thematic experience where the movement of terrain manipulation is palpable.

6.22 Diego Carreras, Y3 ‘Echoes of the Silver Screen’. Through the lens of a film school, visitors to Epping Forest reframe their understanding of the forest’s landscapes. The film school acts as a theatre for multiple spatial experiences to simultaneously unfold. Visitors explore stage sets in which they navigate roles of acting and viewing the performance taking place. Metal surfaces are treated as actors in the scene, as their tailored finish dynamically transforms the spatial boundaries of the landscape.

6.23–6.25 Sean Ow, Y3 ‘Generative Morphologies’. Under the guise of a field centre for Natural England, the project situates itself within a peri-urbanisation masterplan that stretches across Epping Forest. Inspired by the design practice of ruination, the building forms the backdrop of an architecture that ‘humanises nature’. It embodies and registers the calibrated and arbitrary nuances of weathering and habitation through the poetics of additive decay.

Stefan Lengen, Ben Spong

This year UG6 explored the notion of calibration and pursued our interest in the latent qualities of London’s intermediate space, between rural and urban landscapes. We considered our architectures as ‘tuning instruments’ – responsive constructs that ask questions of our environment rather than seek to impose answers upon them. As such, our approaches were necessarily experimental, constructing the means to provoke and listen, suggest and adjust, posit and mutate, as we perpetually rediscovered the questions we asked. We also considered their relationship to the broader ecology of our site of Rainham and Wennington Marshes, just off the Thames Estuary. This held us throughout the year in the captivity and productivity of the uncertain as we created worlds that calibrated from, and towards, multiple origins.

We began the year by dissecting the site. To do so we built digital and physical instruments that aimed to reveal, accentuate and measure a site phenomenon. As we delved through layers of history, geology and environmental change, we repeatedly tested and refined both instruments and methods. Our instruments developed a specificity and precision that stored and produced knowledge through speculative interjection, experimenting with local materials and sensitive recording.

In the building project, our term one instruments were translated and developed into building proposals that adopted equally innovative, local and experimental construction methods and material choices for a range of diverse communities. While each project addresses its own specific context, they share a common ground in acknowledging the open-ended nature of something in the act of calibrating. Such a state is receptive and responsive to change and imaginative opportunities, pointing towards a more diverse and pluralistic built environment.

Our field trip this year was to Copenhagen and Aarhus. In these cities we shared, discussed and learned about the intersections of our research with the Aarhus School of Architecture, the Royal Danish Academy (CITA and Architecture and Extreme Environments) and the Danish architecture practice Vandkunsten.

Year 2

Clive Burgess, Ilia Cleanthous, Andrew Fan, Hsiang-Yu (Sean) Fan, Serena Haddon, Duncan McAllister, Bryan Png Yiliang

Year 3

Ana-Maria Cazan, Shouryan Kapoor, Zofia Lipowska, Alexandria Pattison, Nicolas Pauwels, Luke Saito Koper, Eoin Shaw, Thananan (Orm) Sivapiromrat, Jerzy (George) Szczerba, Kate Taylor, William Tindall

Technical tutors and consultants: Ivan Chang, James Della Valle

Critics: Jenna Alali De Leon, Dimitris Argyros, Joseph Augustin, Cephas Bhaskar, Theo Brader-Tan, Christopher Burman, William Victor Camilleri, Ivan Chang, Nat Chard, Peter Cook, Pedro Gil, Jessica In, Luke Jones, Kyriakos Katsaros, Paul Kohlhaussen, Chee-Kit Lai, Emma-Kate Matthews, Ana Monrabal-Cook, Ho-Yin Ng, Farlie Reynolds, David Shanks, Colin Smith, Greg Storrar, Isaac Palimiere-Szabo, Ivana Wingham

Special thanks to UCL Here East and the team at B-made, Alicia Lazzaroni and Chris Thurlbourne from the Aarhus School of Architecture, David Garcia and Tom Svilans from the Royal Danish Academy, and Thais Espersen and Søren Nielsen from Vandkunsten Architects

6.1, 6.18–6.19 Ana-Maria Cazan, Y3 ‘Embracing the Flood’. Water is the core design element in this therapy centre that is reactive, responsive and open to the natural tidal movement in Rainham Marshes. As tides reveal and flood the building and surrounding landscape, the building experiences dramatic transformation multiple times a day, blurring the boundary between the architecture and its environment.

6.2–6.3 Kate Taylor, Y3 ‘Laying the Groundworks: Designing the Unfinished’. Through a detailed exploration of mistranslated manufacturing processes, this project proposes the groundwork for an architectural testing site. Set in a desolate marshland, the manipulated landscape provides cues for locating permanence: at any one time there exists just enough design to enable future architectures but not enough to shut down potential.

6.4–6.6 Nicolas Pauwels , Y3 ‘Rainham ’40 from Pavilion2pix’. Situated on Rainham Marshes, a site soon to change, the project places a bid for Rainham Festival. Set to inaugurate the new phase of its development, it draws on the former structures along Coldharbour Lane and the Rainham landfill. Through live CGAN image-to-image conversion, the pavilions and constructions offer digital outputs through the navigation of physical inputs.

6.7–6.9 Zofia Lipowska, Y3 ‘Space Between’. In a place where a sunny landscape infused with a sweet rosehip smell can turn into grey, foggy scenery scented with algae stands a lonely building. Here architecture is a mise-en-scène for the play of shadows, based on film noir aesthetics and theatrical techniques tested through the material context of the marshes. It accommodates the surreal sensation of being in between two spaces: the space one is physically present in and the space in one’s memory evoked by scent.

6.10, 6.26 Shouryan Kapoor, Y3 ‘The Cacophonous Lies of the Sonic Realm at Rainham’. Through the creation of devices that augment sound waves from Rainham, the project is an investigation into acoustic control and transformation, and the sonic potential of architecture. An ‘impossible’ hotel is proposed where spaces accommodate visitors’ emotions through the use of sound and noise.

6.11–6.12 William Tindall, Y3 ‘Earthen Deliberation: A Tellurist’s Manifesto’. A prospective vision of architectural education is proposed. Achieved as a consequence of a profound understanding of material culture, the relationships created between material palettes and the building fabric they exist within, the project outlines the preparation and development of an extension to The Bartlett School of Architecture situated in Rainham Marshes.

6.13 Andrew Fan, Y2 ‘The Nestled Gallery’. Acting as a convergence point between the marsh and the River Thames, the building is enveloped in thick earth walls. It creates an enclosure that opens up spaces for lighting conditions and is calibrated to allow light to activate elements of art pieces.

6.14 Bryan Png Yiliang , Y2 ‘The Secular Burial Ground’. To deal with the rising demand for burial grounds in London, the project presents itself as a secular space that accommodates both secular and religious funeral practices. The project acts not just as a landscape for remembrance, but as a landscape that invites visitors to dwell within it.

6.15 Clive Burgess, Y2 ‘Prep: Optimistic Design for Degradation’. The project begins with performancebased research into stability on the foreshore. This provokes the design of an archive of subjective and objective readings of the site, designed to be forgotten and misremembered by a series of occupants over a long period of time. The building is an artefact, configured to take on new forms for new functions.

6.16–6.17 Eoin Shaw, Y3 ‘Are You Bewildered Yet?’. Approaching architecture from the position of unknowing bewilderment, an arrangement of stones topped with spiky and floppy metal hats sat on carbon fibre cushions is created. Clear classification is avoided. The architecture instead encourages users to embrace bewilderment, so the forms, spaces and constellations created can be enjoyed with minimal definition and therefore exclusion of what they are or are not.

6.20 Duncan McAllister, Y2 ‘Monument to a River Pebble’. The river pebble finds its resting place on the tidal beaches of Rainham. The building is a spatial transition from the mundane to the sacred, finding refuge in a sanctuary, where the river pebble is presented as a deity of the River Thames. The project emphasises the interplay between the grand scale of the Thames and the intimate scale of a pebble.

6.21 Jerzy (George) Szczerba, Y3 ‘Illusion of Site’. The work combines views of scenes around arbitrary axes on Rainham Marshes to test how alternative perspectives can reveal different parts of observed situations. Every constructed scene appears complete but, at the same time, can never provide total certainty about what is happening. These ideas are played out across the design for a music school and theatre.

6.22 Thananan (Orm) Sivapiromrat, Y3 ‘Junkology’. Landscape crafted by the act of child’s play. A collage of trained AI-studied images emerges from pattern and texture recognition based on children’s drawings of playscapes.

6.23–6.25 Alexandria Pattison, Y3 ‘A Ceramic Scape: The Anodyne Effect of Rainham Marshes’. In a picturesque aquascape beneath Rainham Marshes lies an abundance of London clay. The vernacular material inspires the programme, with its malleability offering a natural geometry which sits alongside robotic choreography. The project proposes an art therapy space for the locals of Rainham to immerse themselves in the healing nature of the marshland’s beauty.

6.27 Luke Saito Koper, Y3 ‘RNLI-239 Rainham Lifeboat Station’. A buoyant self-righting deployable for coastal and estuarine operation, calibrated to extremes in remembrance of the 1953 flood. Anchored to a turbulent history of defence, security and conservation yet erasing its presence among the fog and ever-changing waterline, the aluminium assembly acts as a sentinel to the portents of tidal cut-off and rising sea levels.

6.28 Ilia Cleanthous, Y2 ‘The Stage and The Staged’. Situated amid an industrial landscape, a landfill and the picturesque Rainham Marshes, the building assumes the role of a stage where the dynamics between the audience, actors and structure are continuously negotiated. Through an open-ended making methodology, the project embraces the process, allowing for the exploration and uncovering of hidden potential beyond its initial design intentions.

6.29 Hsiang-Yu (Sean) Fan, Y2 ‘Rainham’s Choreographed Dialogue’. This project proposes an architecture with moving systems integrated within its fabric to constantly calibrate to scenarios of various activities and occupations. It achieves this by choreographing meaningful relationships and dialogue between spaces, users and the Rainham landscape, resulting in an architecture that always responds with a purposeful outcome.

6.30 Serena Haddon, Y2 ‘Reedhouse’. The fundamental idea of the project was to design a well-crafted and appropriable timber framework that calls for continuous reinterpretation by the occupant with the use of reeds. This project imagines a meaningful vernacular for Rainham Marshes that behaves as an operable, outward-looking tool rather than an envelope.

Stefan Lengen, Jane Wong

UG6 conceives new spatial experiences and experimental typologies. We encourage rigorous dialogue between drawing and making, the real and the fantastical. This year we sought ‘third landscapes’ across the British Isles and beyond as sites for a year-long research and design enquiry. The notion of the ‘third landscape’, first coined by the French designer, botanist and writer Gilles Clément, was articulated largely in the context of urbanism and ecology, referring to the liminal spatial conditions in the built environment and the exceptionally diverse biological communities they harbour.

UG6 posits that when these ‘third landscapes’ are understood in relation to the conditions of their abandonment – whether this be political, economic or social – they can be reimagined as spaces for new forms of use and exchange that challenge the market-driven processes shaping much of the built environment.

From the fragile peatlands of the Flow Country, Scotland to the abandoned salt pans of Molentargius, Sardinia, sites were selected by each student based on a deep and personal interest.

Building upon precise site analysis, students speculated on a new reading of these ‘third landscapes’, reimagining human and non-human relationships with respect to history, culture and contemporary networks of communities, infrastructure and public amenities.

These manifested as spatial strategies and imaginative, site-specific programmes such as new post-contamination social infrastructures, the repurposing of salt production ruins for a new bathing culture and the introduction of cradle-to-cradle grazing settlements for marshland rehabilitation.

Through experimentations in making, digital fabrication and testing, projects were developed through intuitive design and tacit knowledge. These informed alternative architectural visions, creating precise spatial armatures and an architectural presence that celebrates the idiosyncrasies of each place while responding to precise environmental conditions, from open-air boggy courtyards to typhoon-adaptive kinetic roofs.

Based on rigorous investigations and a field trip to Flimwell Park and Dungeness, UG6 students discovered and experienced a plethora of experimental construction methodologies. These sparked an array of projects, from reframing views of an at-risk habitat to relocating the first UK climate refugees, all serving to reveal, augment and cherish neglected qualities and communities. Together they reimagine ‘third landscapes’ as sites of alternative ecological and socio-political relationships.

Year 2

Shujian (Bob) Bao, Adam Butcher, Sofia Forni, Magdalena Gauden, Luke Gifford, Claudiu-Liciniu Horsia, Julia Rzaca, Julia Specht, Sidre Sulevani, Nicole Zhao

Year 3

Pui (Benson) Chan, Rhiannon Howes, Minhe Li, Mufeng Shi, Henry Williams

Thanks to all the structural and environmental consultants who have worked with individual students to realise their projects. Special thanks to Maria Fulford and Sal Wilson

Thanks to our workshop tutors for their remarkable commitment and dedication: Carlota Nuñez-Barranco Vallejo, Ben Spong, William Victor Camilleri

Critics: Nat Chard, Zachary Fluker, Ocian Hamel-Smith, Steve Johnson, Margit Kraft, Perry Kulper, Ifigeneia Liangi, Ana MonrabalCook, Toby O’Connor, Luke Pearson, Joel Saldeck, Daniel Wilkinson, Ivana Wingham

6.1 Julia Specht, Y2 ‘History Is in the Mud: A Community Research Centre for Tollesbury Wick’. The project addresses and negotiates the tensions between archaeological activities, habitat preservation and public access at Tollesbury. It proposes a community research centre that treads and rests lightly on the ground, providing space for multidisciplinary research that engages the local community and visitors in active fieldwork, nurturing a wider cultural consciousness of the environmental and historical value of the territory. 6.2–6.3 Adam Butcher, Y2 ‘The Dance between Land and Sea: Residence for a Coastal Custodian’. The project challenges the notion of defence in the context of erosion and rising sea levels, and poses an alternative approach to negotiating the constant state of flux found along the littoral edge of Benacre Broad. It puts forward the character of a coastal custodian who develops a deep understanding of and engagement with nature.

6.4 Luke Gifford, Y2 ‘The Natural Museum: A Peatland Rehabilitation Centre for the Flow Country’. The project investigates the fragile ecosystem of the Flow Country in Scotland and its rich archaeology. It addresses the misguided perception of peatscape as wasteland and highlights its significance as a major carbon sink. The project proposes a new reading of the territory as a natural museum. A research facility is envisioned for scientific fieldwork and peat rehabilitation, engendering a new form of care and appreciation for the region 6.5–6.6 Minhe Li, Y3 ‘Mining Culture: A Cultural Park for Wheal Coates Mine’. The project speculates an alternative post-industrial vision for the mining district of St Agnes to transform the industrial ensemble into a park with cultural programming. Architectural fragments are repurposed and reinterpreted for projections, animation and other forms of cultural activity. Through these interventions, a conservation strategy is developed to stabilise the industry’s remains while facilitating new use.

6.7 Claudiu-Liciniu Horsia, Y2 ‘Harvesting at the Delta: Poetics and Functions of the Danube’. Throughout the centuries, the Danube Delta has been a place for those seeking refuge from hostile social and political conditions elsewhere. The project focuses on the Dobrogea region of Romania and responds to Lipovan traditions, beliefs and ways of living. The project proposes a design that focuses on the Lipovans’ main trades in reeds, grains, fish and clay as a network of resources that is continually evolving.

6.8–6.9 Nicole Zhao, Y2 ‘The World It Comes From: A Tidal Boat-to-Plate Restaurant’. The project develops an analysis and reinterpretation of landscape devices created by humans – from fish traps to oyster pits –based on deep knowledge of the local conditions of the Blackwater Estuary. Reflecting on the environmental consciousness embedded in those devices, a restaurant is proposed to celebrate the gifts of the estuary and embrace the forces and cycles of nature.

6.10 Shujian (Bob) Bao, Y2 ‘Carving an Inhabitable Landscape: An Excavated House and Workplace’. The project proposes a post-industrial vision for the remaining terraces of Shoreham Cement Quarry to nurture the emerging ‘third landscape’ and provide a home for a gardener and a sculptor, so as to slowly rejuvenate the entire quarry over decades.

6.11–6.12 Mufeng Shi, Y3 ‘Negotiating Precarity: A Communal Typhoon Refuge for Yantian’. The project investigates the topographical and environmental conditions that transformed Yantian into one of the most productive landscapes in the world. These same conditions render the port and its community vulnerable to forceful typhoons, extreme weather conditions and flooding. Recognising the precarious conditions of port

workers and the lack of community infrastructure, the project proposes a reactive typhoon refuge for the local community.

6.13 Pui (Benson) Chan, Y3 ‘Gruinard’s Redemption: Rehabilitating Contaminated Landscapes’. The project investigates the processes of contamination of Gruinard Island in Scotland. It challenges the exclusionary nature of conventional decontamination operations, and puts forward an alternative strategy of rehabilitating the territory through a socially inclusive process of construction. The project proposes a community research centre that embodies the contaminated earth, which over time neutralises and transforms into a memorial to the island’s history.

6.14–6.15 Julia Rzaca, Y2 ‘Out There in the Darkness: New Landscape Rituals for Dartmoor’. The building proposes a revival of the ancient Dartmoor druidical myths and their relationship to territory at large. With a dual programme, it revolves around two main ideas of reclaiming the landscape: the physical act of walking and the ritual of potion-making.

6.16, 6.18 Henry Williams, Y3 ‘A Village Being Abandoned: A Socially Inclusive Spatial Strategy for Fairbourne’. Against the imminent threat of sea-level rise and acceleration of coastal erosion, the project analyses and critiques the UK’s decommissioning process for the village of Fairbourne. It speculates a nuanced and inclusive strategy that negotiates the tensions between resistance and retreat, and creates new conditions for an intergenerational community.

6.17 Sidre Sulevani, Y2 ‘The Afterlife of the Royal Docks’. The project charts the transformation of the site of the Royal Docks from marshland to the service yard of the British Empire, and speculates alternative visions for its post-empire future. Responding to the lack of community amenities and leisure facilities for the inhabitants of the neighbourhood, it proposes a kayaking leisure centre with spaces for all ages and abilities.

6.19–6.20 Sofia Forni, Y2 ‘Choreographies in Bodies of Salt Water: A Communal Bathhouse for Molentargius’. The project develops a careful analysis of Molentargius’ relationship to salt, from its history of prolific salt production to its modern-day recreational use and tourism in the salt works. Addressing the contemporary social gap between locals and visitors, the project reimagines the vestiges of salt basins as a communal bathhouse, where the boundaries of public and private life blur, providing space for social exchange and relaxation.

6.21 Rhiannon Howes, Y3 ‘Nationalising Saltmarshes: A Spatial and Political Strategy for the Estuaries of the South-East’. The project challenges the political shortsightedness and ecological illiteracy that have led to the misunderstanding and mismanagement of the UK’s estuaries and their intertidal marshes. These habitats have been gradually disappearing due to human terraforming of the shoreline, accelerated by climate change and rising sea levels in what has become known as the ‘coastal squeeze’. Stretching across the coastline between the Thames and Orwell rivers, the project reframes the saltmarsh as a national infrastructure.

6.22–6.23 Magdalena Gauden, Y2 ‘Cradle to Cradle: Regenerative Futures for Toruń’s Fortified Landscapes’. The project develops a radical reading of Toruń through the analysis of its ground conditions, which were dramatically transformed by geomorphological and human forces. Focusing on one of the city’s fortresses, the project proposes a permaculture centre that harnesses the lay of the land and its associated ecological and social networks. It nurtures a circular economy of production that reconnects the local community with its unique ecosystem and topography.

UG6 begins from the position that in order to halt the progress of ecological breakdown we need to radically rethink the logic of current construction methods, the materials we use, our approach to growth and our understanding of both value and time. In doing so, it is likely that we will need to both recover some of our forgotten technologies and develop entirely new forms of architectural language.

We are interested in developing qualitative prototypical buildings, which are ecologically founded, economically viable, and positively impact their inhabitants’ lives through considered design and accessible adaptability. In a climate in which warranties dictate design, and the nature of construction contracts limit quality, we seek to redistribute the priorities of the construction process in favour of design and sustainability.

Our proposals are designed to be factory made, involving different forms of prefabrication and drawing on the material resources and infrastructure of the surrounding contexts. They combine the efficiencies, improved labour conditions and precision of the factory with ancient building technologies and materials. Each building is a model, a design that can be reproduced and reconfigured many times and in many different contexts.

Students’ proposals are sited as part of the Aylesbury ‘Garden Town’, a government housing initiative drawing on the principles of Ebenezer Howard’s Garden Cities. The site is intended to be at once specific and generic, to enable the propositions to be tested against context and in relation to each other. Together the buildings form a broader urban proposition that constitutes a self-sufficient town with its own housing, community buildings and productive spaces.

Along the way, we have been modelling and testing at different scales, with an emphasis on the direct use of materials and 1:1 fabrication. We began our year with a trip to the brick factory HG Matthews, where each student designed and made a chair. We ended our time on campus at Here East, midway through the fabrication of a pavilion for the New Art Centre in Salisbury, for which the unit collaboratively designed a pavilion building using prefabricated timber cassettes with an innovative clay and hemp infill. Making brought us into contact with the tactility of these processes and enabled us to learn with our hands. We have interrogated how material and industrial cultures shape the world, and creatively challenged regulations, supply chains and processes in order to produce proposals that offer a radical yet viable alternative to the status quo.

Year 2

Nasra Abdullahi, Marius Balan, Sophia Brummendorf Malsch, Latisha Chan, Thomas Keeling, Sara Mahmud, Yerkin Wilbrandt

Year 3

Maria De Salvador, Bengisu Demir, Christina Economides, Evelyn Salt, William Zeng

Thanks to our consultants

Simon Herron, Luke Olsen, Peter Laidler, Will Stanwix

Thank you to our critics Barbara-Ann CampbellLange, Mollie Claypool, Amica Dall, Lettice Drake, Sam Little, Bob Sheil, Richard Wentworth

6.1 UG6 ‘One-Day Chair Project’. Using hand tools and palette timber, over the course of a single day each student designed and made a chair which reflected the structural principles of a different timber-framed building case study. These were built and photographed at HG Matthews Brickworks.

6.2, 6.8 Christina Economides, Y3 ‘The Homegrown Agora’ is a project which speculates on the possibilities which emerge from an integration of nature and architecture. Reframing agricultural waste and the growth of fungi as valuable resources for the production of biomaterials, the proposal explores how we can build with locally produced bio-based materials as substitutes for the high-embodied carbon products prevalent in the building industry. It is both a building and a system which incorporates growing, producing, using and decomposing materials.

6.3 Evelyn Salt, Y3 ‘New Urban Plan for Aylesbury Garden Town’. This site plan shows a cooperative housing proposal in the context of an urban plan developed collaboratively by the unit, with a number of different prototypical housing models arranged in organic clusters around communal green spaces. The project is situated within the new ‘garden town’ development of Aylesbury, the masterplan of which UG6 have redesigned in order to create community-centred spaces, where the programme, position and design of the buildings gives the town a distinct sense of place.

6.4, 6.9, 6.18 Maria De Salvador, Y3 ‘Mass Timber High Rise’. This proposal explores the use of mass timber frame structures in high-rise residential towers, and the potential role of the column in this system as both a structural and a spatial device. The mass timber structural columns free up the internal walls to vary from storey to storey, forming a series of dynamic private and public spaces. The plan leaves room for potential change and unprogrammed activities to take place, anticipating but not prescribing its future uses.

6.5 William Zheng, Y3 ‘The Chill Garden’. This project addresses the complexities of societal stress, and the desire to be both part of and apart from, the group. The proposal is for a densely occupied residential block with a carefully curated gradient of space, which navigates from the public social to the private realm. The design was developed through the interrogation of viewpoints and the experiences of the viewer and the viewed. The enclosures and openings that define the spaces have been calibrated materially and formally to recognise inherent social choreographies and promote social ease.

6.6–6.7 Thomas Keeling, Y2 ‘Earthside Terrace’. In this project, conversations between residents over light, land and space are resolved in negotiation between the hills and the walls. The outcome is a 43% reduction in basic construction costs; and an affordable, tailored neighbourhood which is embossed into the hillside. Construction techniques are exposed and celebrated: encouraging inhabitants to repair, retrofit and expand their homes as their relationship with the typology develops. This proposal aims to impact beyond the single instance of this development, shaping attitudes towards construction and reimagining our historically imbalanced relationship with nature.

6.10–6.12 Evelyn Salt, Y3 ‘The Bathhouse’. This project addresses how spatial and material decisions can help create the conditions for intimacy in an increasingly isolated society, explored through a prototypical co-operative housing typology composed of a primary in-situ timber frame and prefabricated hempcrete infill cassettes. Inward-facing openings are privileged over outward-facing ones, with large pivoting windows creating moments of connection across a courtyard allowing for relationships to be established at a distance and

generating an experience of togetherness. The ground floor of the building provides flexible social, communal and commercial space. In this instance it is shown occupied by a bathhouse, the communal spaces of which provide moments of encounter and interaction, places where relationships are formed and that foster a sense of community.

6.13, 6.15 Sophia Brummendorf Malsch, Y2 ‘Redefining the Rural’ investigates how our relationship to landscape and agriculture can define what living rurally looks like. It is a response to the unavoidable tension between enforced control over landscape through traditional agricultural practices, at the expense of complex forest ecosystems. The project proposes a provocative strategy of densification of agriculture and housing as a way of liberating arable land for reforestation. The building is designed for reconfiguration as well as disassembly, using prefabricated components that sit within a larger timber frame, which allows residents to customise their living space to their current and future needs.

6.14 Sara Mahmud, Y2 ‘Revolutionising Post-Factory Culture’. In the context of a growing disconnect between the places where things are bought and the places where things are made, this project advocates the reintroduction of manufacturing spaces into residential neighbourhoods, where communities can better understand the impact of their choices on the environments in which they live. The proposal is a series of small-scale fabrication workshops which coexist with one- and two-bedroom flats, exploring the interconnection of domestic and productive space and the potential for shared spaces between these two programmes.

6.16 Bengisu Demir, Y3 ‘The Talking Laundrette’. This project investigates how natural materials and passive systems can help create low embodied energy solutions for everyday life. The proposal is a series of apartment blocks, joined together by a communal laundrette where the residential community can gather, interacting with one another in the processing of carrying out often unacknowledged domestic labour. In exploring the social and ecological potential of rethinking the way we wash and dry our clothes, the building addresses both the material and cultural shifts necessary in a low carbon future.

6.17 Latisha Chan, Y2 ‘Healthcare at Home’. This project explores the notion of care, and the extent to which a building’s material palette and programme can positively impact the lives of its inhabitants. The proposal is a sustainable housing model, which integrates a series of social spaces promoting both physical and mental wellbeing. Natural and low embodied carbon materials were carefully chosen for the structure and finishes, and a central hanging garden creates a microclimate of purified air. Prefabricated systems allow the building to be constructed quickly. The project envisions a future where housing developments across the country incorporate this new typology.

Tilt-Shift: Long Views Across the Edo

Farlie Reynolds, Paolo Zaide

Farlie Reynolds, Paolo Zaide

Japanese ukiyo-e – meaning ‘pictures of the floating world’ –are woodblock prints that were intended to provide escapism from everyday 17th-century life in Japan during the Edo period. Stitching together stories of people, spaces in nature and the changing of the seasons, ukiyo-e depicted imagined societies where folklore, erotica and wild landscapes were in abundance. Today, Tokyo’s dazzling neon backdrop is a dramatic shift from these dreamlike floating worlds. But between the subtle transience of the old capital and the digitally enhanced frenzy of Tokyo remains a culture inherently bound by tradition, craft and nature.

This dialogue between tradition and modernity is embodied in the tactility of the moss garden, the diffuse light of the shoji –traditional Japanese doors made with translucent paper – and the engawa – a narrow Japanese veranda that forms an ambiguous passageway between dwelling and garden. Caught between shoji screens and the outer storm shutters, the engawa exists as a blurred threshold – a space that is neither inside nor out – and is a space for conversation or for observation of the slow passing of the seasons. This space reflects Japan’s traditional reverence for natural life and the environment. Originally absent from the Japanese language, ‘nature’ was considered so integrated with the everyday experience that there was no impetus to conceptualise it as its own entity. Technology was embraced as a means to adapt to the natural world and to passively extract resources, establishing a symbiosis between traditional Japanese craft and nature. Architecture, thus, became dependent upon its context rather than an artificial imposition within it.

Today, the paradox between Eastern and Western approaches in Japan typifies the tension between nature and culture: both are in constant motion, slowly tilting between extremes, forcing us to speculate on how our environment might recalibrate when one radically shifts. This year, UG6 confronted this changing environment. We negotiated small tilts and big shifts – shocks caused by abrupt changes in nature or culture – and questioned how everyday spaces and urban landscapes can adapt to accommodate environmental uncertainty. Our focus was Tokyo Metropolis, a model ‘disasterresistant city’ that has undergone a number of changes to withstand potential environmental impacts over the years. Searching beyond the pragmatic, we interpreted the notion of ‘shocks’ and the ‘environment’ from a cultural perspective. This year’s brief was an invitation to journey through Japan’s traditional and contemporary narratives, to stitch into the rhythmic tempo of Tokyo and to bind age-old techniques and materials with new technological inventions.

Year 2

Renee (Soraya) Ammann, Tengku (Sharil) Bin Tengku Abdul Kadir, Cira Oller Tovar, Ewa Roztocka, Natalia Sykorova, Chak (Anthony) Tai, Milon Thomsen, Long (Ron) Tse, Suzhi Xu

Year 3

Chun (Jason) Chan, Hiu (Victor) Chow, Migena Hadziu, Zhongliang (Abraham) Huang, Yuen (Peter) Kei, Kit Lee-Smith, Owen Mellett

UG6 would like to thank our guest critics: Laura Allen, Barbara-Ann Campbell-Lange, Edward Denison, Christine Hawley, Ness Lafoy, Inigo Minns, Caspar Rodgers, Gregory Ross, Emory Smith, Kit Stiby Harris, Sabine Storp, Jessie Turnbull; and friends of the unit, Theo Clarke, Maxim Goldau, Kerry Lan, Shiyin Ling, Jerome Ng, Yip Wing Siu

Thank you to Robert Newcombe for our photography workshops, to our computing tutor Jack Holmes and our technical tutors Clyde Watson and Dimitris Argyros

For their warm hospitality we would like to thank Toshiki Hirano from the Kengo Kuma Lab, Kaz Yoneda and Momoyo Kaijima for introducing Tokyo from the Atelier Bow Wow Terrace. Finally, we would like to thank the Daiwa Foundation and the Great Britain Sasakawa Foundation for their generous support this year

6.1 Migena Hadziu, Y3 ‘Archipelago/Dichotomy’.

This project proposes a DNA research and archive facility for the ex-military Daiba Park island in Tokyo Bay. The architecture bridges the gap between time and materiality by reacting to the conditions set out by the process of preservation and manipulation of the site, allowing the building to keep evolving in parallel to the research development.

6.2 Natalia Sykorova, Y2 ‘Museum of Forgotten Territories’. This project accesses the inaccessible through reconstruction of a non-existent village. A territory of the Burakumin – an outcast community considered to be at the bottom of Japanese society –the village has been left and consciously forgotten to suppress discrimination. The proposed building communicates collisions and disassociations within Japanese society through the process of leather-making.

6.3–6.5 Kit Lee-Smith, Y3 ‘Anthropogenic Tectonics’. The UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage programme promotes education and preservation, adopting traditional Japanese attitudes, rather than Western material archiving. The design for a ‘seismic proving ground’ within Tokyo Bay aims to celebrate new technologies, investigates seismic activity around liquefaction – whereby the strength of soil is affected through an earthquake or similar force – and searches for a future treatment for design on reclaimed land.

6.6 Long (Ron) Tse, Y2 ‘Juku with the Falling Eggs’.

In response to the rigid yet inefficient Japanese education system, the project explores the new typologies of learning environment for students aged between 3 and 13. Inspired by Bruno Munari’s ‘Tactile Workshops’, the scheme proposes a learning landscape and chicken farm that encourages children to learn through physical interaction, play and creativity.

6.7 Hiu (Victor) Chow, Y3 ‘Hesei Shrine Complex’. This project looks at the deconstruction and desecularisation of the traditional Japanese religion Shinto, with the aim of creating shrines with metaphysical boundaries, in contrast to traditional walls and gates, where enshrined objects have been closed-off and people have been forgotten. The project reminisces on the memories of the Tsukiji Fish Market and Heisei era, whilst looking forward to the revitalisation of Shinto and the future of the new emperor.

6.8–6.9 Suzhi Xu, Y2 ‘Kyo no Shiki – Four Seasons of Kyoto’. By studying the daily rituals of geisha, the tradition of ‘revealing and concealing’ is reinterpreted in this project through the redesign of a kimono and in a performance. The performance became the foundation of an installation on Tokyo’s streets, revealing and concealing fragments of Kyoto and the dying beauty of geisha culture.

6.10 Owen Mellett, Y3 ‘The Flooding Japanese Garden’. This landscape intervention sets a precedent for the further development of Tokyo, integrating flood control with the creation of new public garden spaces. By inhabiting and reconstituting the bottom floors of buildings close to important flood points, the project creates an ever-shifting garden space. Surrounded by a forest of support columns, among which the inhabited structures sit, the garden retreats, shifts and unfolds as the water level changes to ensure this public space is always inhabitable, regardless of the changing environmental conditions around it.

6.11–6.12 Tengku (Sharil) Bin Tengku Abdul Kadir, Y2 ‘Nha – Home for the Vietnamese Immigrant’. A proposal for a co-housing scheme for the new Vietnamese immigrant and the Japanese university student, designed in response to a controversial immigration bill by the Japanese government. Learning and exchange are facilitated onsite through the use of adapted vernaculars and myths from both cultures.

6.13 Chak (Anthony) Tai, Y2 ‘Salaryman’s Genkan’. Inspired by social problems relating to harsh working conditions in Japan, this project investigates extensions to the home that help people to de-stress after work. Using the engawa spaces commonly found in traditional Japanese homes, a series of scripted, organic landscapes in the form of ‘plug-ins’ create a new conversation around the conventional daily routine.

6.14 Yuen (Peter) Kei, Y3 ‘Mikoshi Lion Festival’. Due to the redevelopment of Tsukiji Fish Market in Tokyo, the annual matsuri (festival) is disappearing. This project incorporates public and private spaces allocated to the festival’s parade route and, also, workshop facilities for building celebratory structures. A mikoshi lion head is constructed above the workshop area as a symbolic display of Tokyo’s dynamic cityscape.

6.15 Renee (Soraya) Ammann, Y2 ‘A Night-time Retreat’. Situated in Dogenzaka, Tokyo – where the night is always young, and the drinks never stop coming –this programme offers a place of rest for those wanting to escape it. Designed for the average party-goer and worker, it incorporates laundry, bathing and sleeping facilities packaged in the format of a deconstructed Katsura Imperial Villa.

6.16 Milon Thomsen, Y2 ‘Towards a ‘Bonsai’ Architecture: Multigenerational Living in Tokyo 2090’. With Tokyo’s ageing population set to halve by the end of the century, this project seeks new strategies that might preserve the city’s vitality through subtle subtractions and additions to existing building typologies. By connecting the disjointed urban structure and breaking with the unsustainable ‘demolish and rebuild’ philosophy, insertions of hanging gardens create new common ground for social interaction, learning and care between the young, working and elderly populations.

6.17 Zhongliang (Abraham) Huang, Y3 ‘Arrow to the Sea’. This project counters the ecological damage caused by the Tokyo 2020 Olympics in the form of a traditional Japanese martial arts centre, located in Tsukiji. In order to bring tranquillity back to the site, bamboo forests will be planted in and around the main architecture, where people can practice martial arts and Japanese archery, and enjoy the peaceful view of the bamboo forest and Tokyo Bay.

6.18 Ewa Roztocka, Y2 ‘Renewal of Shitamachi’. This project is set on the historical border between the Yamanote and Shitamachi areas in Tokyo, constructing a bridge on the border for contrasting social and urban patterns to meet. In it, lost personal memories and belongings of the forgotten lowland Shitamachi cultures are celebrated through craft. The design seeks to revive the Shitamachi area, in particular its housing, and promotes local Shitamachi craft.

6.19 Cira Oller Tovar, Y2 ‘The Streetscape of Asakusa’. In contrast with the civic squares seen in Europe, villages and districts in Japan have an axial organisation. This village structure, with no visual endpoints, would appear to signify the lack of importance placed on spatial limits. The project explores how different elements merge interior and exterior, and private with public spaces in contemporary Japan.

6.20 Chun (Jason) Chan, Y3 ‘Aqua-Vitality Retirement Centre’. This proposal uses architecture to retain the memory of the Tsukiji Fish Market. The building redefines the memory of existing shops, structures and functions. An intersection between Tokyo’s old and new, prefabricated building elements were designed to combine with the existing structure, creating a sustainable Japanese garden and an atmosphere of delight for the older and younger generations.

Gravesbury: 4IR Charlotte Reynolds, Paolo Zaide

Year 2

Amy Kempa, Zakariya Miah, Indran Miranda Duraisingham, Marcus Mohan, Imogen Ruthven-Taggart, Annabelle Tan Kai Lin, Tini Hau Tang, Arina Viazenkina

Year 3

Theo Clarke, Maxim Goldau, Yo Hosoyamada, Tsz (Victor) Leung, Lingyun (Lynn) Qian, Kenji Tang, Ching (Cherie) Wong

UG6 would like to thank our guest critics: Will Armstrong, Peter Bishop, Barbara Campbell-Lange, Andy Friend, Christine Hawley, CJ Lim, Joe Paxton, David Roberts, Sabine Storp, Patrick Weber and friends of the unit George Courtauld, Jin Kuo, Kerry Lan, Enoch Liang, Yiki Liong, Jerome Ng, Max Shen, Sam Tan, Gordon Yip

Thank you to Lynne Goulding and Matthew Carreau from Arup Foresight for the Emerging Futures workshop

Thank you also to Emma Kitley, Robert Newcombe and Yip Wing Siu for running various media workshops, to our computing tutor Jack Holmes and our technical tutors Dimitris Argyros and Clyde Watson

We are on the brink of 4IR – the fourth industrial revolution. Building on the momentum of last century’s digital revolution, 4IR is beginning to merge our cyber networks with our physical infrastructure at an accelerating rate, creating new hybridised environments. With every mile of optic fibre laid and each new artificially intelligent device embedded in the Internet of Things, the ways in which we interface with our physical environment are modified and the ways we interact with one and other are shaped. In this technological storm our culture and economy will be forged. How will these advances fundamentally alter and ultimately challenge our way of life? Intrigued by this fragile tension between cultural tradition and technological progression, this year’s brief was an invitation to enter tomorrow’s brave new worlds.

This year’s programme was sited on the city’s edge, a suburban landscape that will be reinvented with 4IR. Gravesend, once a naval and shipbuilding town, is now a commuter zone that maintains only a small proportion of industrial activity. Across the water, Tilbury remains the principle port of London with a rich industrial history. East Tilbury’s 1932 Bata factory provided a unique model of a company town. Unique to the architecture of Bata Town was its utopian vision of community living that offered a farm to supply the eggs and milk for the guests at the Bata Hotel, tennis courts, football pitches and a swimming pool for the workers’ leisure, and a local cafe complete with an espresso bar and jukebox. Thriving sites of production and manufacturing in previous industrial revolutions, these forgotten factory townscapes are now promised a new lease of life, set to boom with new creative and cultural economies. The factory typology is now being optimised through automation, but how do we picture our homes and neighbourhoods will be? In a digitally oversaturated world, what kinds of spaces do we design in which we can live, learn or simply do nothing?

The connection between these towns was the focus for our main building project: to reimagine the impact of technology on the production, spaces and communities along the Thames Corridor. What will be important for these towns’ communities? How will the hybrid of technology and space support our lifestyles beyond the functional and pragmatic? How will it help to reconnect to its historic past, the societies of today and the ecologies and architecture of tomorrow? With a focus on the community over technology, what types of programmes and forms of living will cater for the welfare, ambitions and dreams of these neighbourhoods? 4IR provides an opportunity to think about how we can connect and reconnect with these virtual and physical realities. Still untested, ‘Gravesbury’ presents a site for sensitive experimentation, wonder and a taste for the unknown.

Fig.6.1 Theo Clarke Y3, ‘Philharmonic for Relics’. Cliffe Marshes, a landscape of decoys, becomes a wetland reserve hiding behind the guise of a controversial proposal for a new London airport. The project immerses itself within this political debate, creating a Potemkin airport to appease political demands, whilst simultaneously preserving the ecological diversity of the Thames Estuary. Fig. 6.2 Arina Viazenkina Y2, ‘Tollesbury Slowscape’. The sanctuary is embedded in the undulating marshlands of Tollesbury, exploiting the natural resources to create a unique environment for palliative care and physical wellbeing. Fig. 6.3 Victor Tsz Leung Y3, ‘Tilbury Future Climates Academy’. Powered by the neighbouring Tilbury Power Station, the school serves as an agricultural education facility for the local communities of Gravesbury whilst hosting

a number of smaller satellite campuses within the cityscape of London. Water serves as the protagonist of the building as it works to heat, cool and irrigate the agricultural production of a controlled, projected future climate to reflect impending climatic extremes. Fig. 6.4 Yo Hosoyamada Y3, ‘Supermarket Collective’. In a society of overconsumption and production, ‘degrowth’ proposes a counter-thesis focusing on cooperation, self-sufficiency, and ‘bottom-up' approaches. The project is a model for a cooperative community which sets itself on top of a supermarket. Parasitically attaching itself to the existing facility, the scheme imagines a landscaped intervention of symbiotic exchange systems between the existing and the new.

Fig. 6.5 Amy Kempa Y2, ‘Resorting to Malt’. Following the degeneration of Gravesend into a commuter town, the project aims to revitalise the area through the reintroduction of lost traditions and community. Malt production drives the building, recycling and reusing waste industrial water to provide a more public aspect of bathing to the otherwise private, industrial processes. Fig. 6.6 Imogen Ruthven-Taggart Y2, ‘Gravesend Pier: A Crafted Intervention’. The project introduces an open creative hub into the shoreline of Gravesend. The language of the interventions aims to bridge the gap between the surrounding industrial landscape and the developing residential town, introducing a place for the community to work, explore and interact. Fig. 6.7 Ching (Cherie) Wong Y3, ‘Gravesend Maritime Academy’. The academy is a critical commentary

on today’s cruise ship industry. The school provides training to local youths whilst exposing the wider community to the unique working environments of the cruise ship by repurposing dismantled parts of the iconic QE2. These typically less visible conditions of the cruise ship industry are highlighted to the public through a series of reconstructed theatrical sets.

Figs. 6.8 & 6.10

Annabelle Tan Kai Lin Y2, ‘Condensed City’. Responding to different industry-centric social models, the proposal explores a new live/work typology to revitalise post-industrial Gravesbury. The scheme harnesses special moments in the landscape to construct a narrative attracting youths, entrepreneurs and digital nomads to create alternative communities along the Thames estuary. Fig. 6.9 Tini Hau Tang Y2, ‘Kitchen Follies’. The project explores the interstice between public and private through a series of suspended kitchens designed to act as common public platforms. A series of digital curtains form a softer interface between the virtual and the real to encourage community interaction. Fig. 6.11 Marcus Mohan Y2, ‘The Maritime Childcare Centre’. Carved out of the existing industrial landscape along the River Thames,

the centre is a playful riverside workroom focusing on experiential learning. The proposal examines the current trends in early childhood education and suggests an alternative way of learning through play, the environment and tinkering. Fig. 6.12 Lingyun (Lynn) Qian Y3, ‘Ama-zone’. Ama-zone depicts a dystopian future in which Amazon builds a giant fort of relocated facilities around its largest UK fulfilment centre in Tilbury. As part of its imagined Tax Avoidance Scheme and Apprenticeship Programme, Amazon offers the residents of Tilbury free training at the Amazon Training Centre and leisure activities in the Amazon Sports Hall to offset its tax bills. The crane-like infrastructure continues to grow over the years and disguises the enormity of the logistical space behind.

Fig. 6.13 Kenji Tang Y3, ‘Butcher by the Bay’. A lab-grown meat production plant and dining experience are embedded within Gravesend’s riverside leisure area and parkland, where the public can actively learn about the scientific processes behind the clean, environmentally responsible food produced onsite. In response to the growing concerns around meat consumption, the project combines two emerging bio-technologies – in-vitro meat and mycelium cell cultivation – to bring a feasible and appetising substitute to dinner tables. Visitors travel along a ‘blood vessel dining route’ within the building whilst enjoying a four-course gastro experience within suspended ‘dining cells’.

Fig. 6.14 Maxim Goldau Y3, ‘Homo Faber’. A growing community of craftsmen revive a barren plot between Tilbury and East Tilbury that has been violated for decades, used for landfill:

this land becomes a ground for industrial tree farming, revitalising local skills and manufacturing in timber production. The new forestry community explores the qualities of inhabiting the woodland, living symbiotically with its cyclical growth in the form of community-built slender modular tower structures, linked by elevated roads, constructed from harvested wood. The tree becomes a keystone of the architecture which forms the village’s constructed and natural fabric.

Year 2

Xavier De La Roche, Yee (Enoch) Liang, Gabriel Pavlides, Max Hanmo Shen, Negar Taatizadeh, Olivia Trinder, Gordon Yuk Yips

Year 3

Nikhil (Isaac) Cherian, Wing (Melody) Chu, Nichole Qi Ho, Kaizer Hud, Shi Yin Ling, Carolina Mondragon-Bayarri, Rosie Murphy, Fola-Sade (Victoria) Oshinusi

Thank you to:

Christine Hawley, CJ Lim, David Roberts, Mike Tite, Patrick Weber, Peter Bishop, Sabine Storp, Stephen Gage, as well as friends of the unit: Emily Priest, George Courtauld, Ivan Hung, Jin Kuo, Joe Travers-Jones, Max Butler, Sam Tan, Yiki Liong, Yip-Wing Siu

Thank you also to our computing tutors Jack Holmes and Joerg Majer and our technical tutors Clyde Watson and Dimitris Argyros

Tim Norman, Paolo Zaide

With today’s fragile borders being redrawn by identity politics, migrationrelated challenges are increasingly something architects must understand and respond to. Just last summer, we watched Rio de Janeiro open the 31st Summer Olympics to welcome athletes from across 207 nations. While the Games presented an opportunity to celebrate the coming together of the global community, other forms of migration today present far greater challenges: in the Mediterranean, the unfolding refugee crisis continues to strain both political and race relations across Europe, while in the US, the newly elected 45th president leads a populist campaign that promises to build an 3,100 kilometre-long “impenetrable, physical, tall, powerful, beautiful, southern border wall” to separate Mexico from the Land of the Free. Back in Britain, after a vote to leave the European Union, businesses begin to relax, as the grey-cloud prophecies of the end to free movement of labour have not yet come true – Brexit, of course, is still to come.

The question of migration might be a complex one, but this year’s theme was an invitation for our imagination to drift and to speculate. This century will see a dramatic rise in different types of migration, from communities escaping from the political or environmental conditions of their home to mobile people who choose to live in other parts of the world simply because they can. With the question of how future migrants will integrate, live and operate in their new host environments the unit continued to consider the organisation of communities, and to explore the architectural design of the individual and shared programmes, spaces and infrastructures. This year’s brief took the optimistic tone of Doug Sanders’ ‘Arrival City’, in which migration, and its inherent goal of resettling people, is presented as one of the great opportunities of our time. The brief was an invitation to explore this theme from the abstract to the poetic – and from the pragmatic to the fantastic. Where do these journeys begin? How do they unfold? Do they end, propagate or simply continue to drift?

The main brief for the year was a challenge to consider the Arrival City beyond the merely pragmatic – what is desirable? What levels of functionality would actually improve the quality of living in our city in fifty years’ time? And how do we integrate qualities of transience, flexibility and adaptation? In a cityscape with shifting territories and ecologies, mobile and settling communities, how do we design spaces that have practical, social and cultural value? What stories can future communities share? The work from the unit is filled equally with optimism, provocation and wonder.

Fig. 6.1 Kaizer Hud Y3, ‘Stepney Hydrosensitive School’. The school aims to stimulate urban water sensitivity by positioning itself as a water recycling interface. Taking cues from Islamic architecture via the local Bangladeshi population, the water system is exposed to incite students’ curiosity. Captured rainwater and grey water from surrounding houses is filtered and used as a resource for play, learning and spiritual reflection. Fig. 6.2 Gabriel Pavlides Y2, ‘School of Landscape Design’. By placing the building along the canal in Mile End Park, students are encouraged to interact with gardens and greenhouses to influence the way people experience nature.

Fig. 6.3 Olivia Trinder Y2, ‘East End Azulejos’. With old Arts and Crafts techniques re-emerging, the project encourages local communities to come together in artisan workshops and

studios for the production of glazed ceramic tiles. Fig. 6.4 Wing (Melody) Chu Y3, ‘The Dunstan Elderly Centre’. The project redevelops two Victorian dwellings in Stepney Green into a mixed-use centre for the elderly, serving the existing residents in the context of the ageing population of 50 years’ time. Fig. 6.5 Nikhil (Isaac) Cherian Y3, ‘Whitechapel Craft Arcade’. As the Whitechapel Bell Foundry announces its departure, the project rejuvenates the future of craft by housing workshop spaces and yearly fairs as a twist on London’s affluent arcade shopping experience. Fig. 6.6 Nichole Qi Ho Y3, ‘Theatre for Storytellers’. A community theatre created as a space for stories to be told through performances and conversations, providing a shared experience to empower the voices of both immigrants and

Fig. 6.7 Carolina Mondragon-Bayarri Y3, ‘Women’s Refuge’. An urban secret garden that assists newly-immigrated women to integrate into their new environment through blurring exterior and interior boundaries by manipulating light, sound and views.

Fig. 6.8 Negar Taatizadeh Y2, ‘Theatre and Performance Spaces’. The project investigates the concept of the building acting as a theatre stage itself, creating surprising moments for visitors as they become part of the act. Fig. 6.9 Xavier De La Roche Y2, ‘Trading Archive’. Reoccupation of a 17th-century almshouse originally built for travelling seamen, and redefining its interior as a network of highly sculptural spaces to provoke a critique of the East India Company’s controversial history.

Fig. 6.10 Max Hanmo Shen Y2, ‘City Farm of the Future’. An alternative city farm typology which also functions as a market

and a playscape that is woven through the stepped pastures of the market roof. Figs. 6.11 – 6.12 Fola-Sade (Victoria) Oshinusi Y3, ‘The Stepney Green Landscape of Transient Accommodation’. Providing three guest accommodation typologies existing alongside current residents, this project focuses on the spatial requirements needed to accommodate residents who will be staying on different timescales: from the long-term comfort and adaptability of existing residents to the short-term needs of overnight residents.

Figs. 6.13 – 6.14 Shi Yin Ling Y3, ‘Anchor Park Mixed Development’. The issue of migration pushes the city of London to grow outwards and upwards. The project instead proposes a low-rise, high-density residential development that integrates ecological density through an interweave of green courtyards and pockets. Fig. 6.15 Rosie Murphy Y3, ‘Intergenerational Agri(Culture)’. The project nurtures the passing on of traditions and knowledge of different cultures, and encourages intergenerational connections by incorporating greenhouses of varying climates that celebrate universally significant activities of growing, cooking and eating. Fig. 6.16 Yee (Enoch) Liang Y2, ‘Whitechapel Carpentry Guild’. The Whitechapel Carpentry Guild looks to revive the fading crafting culture by providing

a testing ground for woodwork that will eventually be constructed around London. Fig. 6.17 Gordon Yip Y2, ‘Adaptive Communal Housing’. A housing scheme focusing on adaptability for individual and communal interests.

Year 2

Alex Desov, Ashleigh-Paige Fielding, Dustin May, Edward Sear, Fan (Lisa) Wu

Year 3

Lester Tian-Lang Cheung, Deedee Pun Tik Chung, Ching Kuo, Xin Hao (Jerome) Ng, Hoi Lai (Kerry) Ngan, Yuchen Pan, Calvin Po, Yip Wing Siu, York Tsing (Nerissa) Yeung

UG6 would like to thank our friends and critics: Bartek Arendt, Abigail Ashton, Paul Bailey, Peter Bishop, Max Butler, Stephen Gage, Jamie Hignett, Alex Julyan, Jens Kongstad, CJ Lim, Anu and Shilpa Mridul, Tim Norman, Emily Priest, Sabine Storp, Joe Travers-Jones, Patrick Weber, Ivor Williams

Special thanks to our technical tutors Matt Springett and Clyde Watson

This year UG6 approached the issue of health from a cultural perspective, looking at both the clinical models of the West and the natural ‘life balance’, which is the more popular alternative across Asian continents. Health is currently a topical subject that, within the UK, can make or destroy political parties as current NHS provision becomes increasingly inadequate. A demographic change will challenge our understanding of conventional medicine and perhaps raise interesting discussions about alternative approaches.

This subject is not just an issue for politicians and the medical community but also for designers; history has shown that groundbreaking design can provide innovative care decades ahead of its time. In 1926 the holistic medical philosophy pioneered by Drs George Scott Williamson and Innes Hope Pearse was offered at the Peckham Health Centre. Both the building and the clinical support radically challenged the tradition of reactive medicine; it emphasised the importance of a socially, mentally and physically balanced lifestyle; it is only now that the wisdom and efficacy of their approach offers a concept that we should consider, if contrasted against the costly science of modern medicine.

In November the Unit travelled to India where we observed attitudes to health and traditional medicine that promote certain similarities to the Peckham Experiment through ideas of holistic well-being, where the body, the mind and lifestyle have to be in balance. Joseph Carpue, born in 1764 in London, studied plastic surgery in India for twenty years and was the first to perform ‘rhinoplasty’ or, as it was known then, ‘Indian nose reconstruction’. What do these medical cultures share and what might they offer us today? And is some of this thinking relevant to the health provision of the future?

The brief challenges concepts of collective and civic health and its place in the contemporary city. The students explored an alternative to the modern primary care centre, currently offering a service that responds only to illness and not to well-being. Why and when do we need medical advice and prescription and how can this be minimised? Set in future Peckham, the projects explored ideas about health and lifestyle that comments on all aspects of what we do, whether it be work, recreation or simply doing nothing.

Fig. 6.1 Deedee Pun Tik Chung Y3, ‘Hydro-Rehabilitation Centre’. This project incorporates hydrotherapy as a remedial treatment for both sports injury prevention and rehabilitation. Situated adjacent to the Peckham Library, the project offers a platform to host events and celebrations in Peckham. It includes diverse suspended water elements which promote mental and social wellbeing. Fig. 6.2 Dustin May Y2, ‘Peckham Food Centre’. Society has become disconnected with the food it eats. The project educates Peckham’s community on the food industry; from cultivation and growing to culinary classes and wider environmental impacts. Fig. 6.3 Fan (Lisa) Wu Y2, Peckham Convalescent Home’. The NHS is under high pressure due to the lack of continuity in social care facilities. Many argue that the current hospital environment is disempowering

for patients, resulting in a slower recovery time. Therefore an intermediary recovery centre is crucial for the community of Peckham. Figs. 6.4 – 6.5 Ashleigh-Paige Fielding Y2, ‘Peckham Hydro-Health Centre’. Over the next fifty years, London will increasingly become a stressful environment. This project aims to weave in moments of tranquility into the urban fabric. The Peckham Hydro-Health Centre becomes the extension of Peckham Square, exposing the forgotten Surrey Canal. The issue of mental health is approached by a series of sensory moments suspended above a sculpted landscape, connected through the overarching theme of water.

Ensure image ‘bleeds’ 3mm beyond the trim edge.

congue pulvinar. Duis consectetur semper gravida. Lorem ipsum

Fig. 6.6 Calvin Po Y3, ‘Peckham Health Common’. This project re-examines the contemporary relevance of ‘common land’ as an intersection of communities and a common site for the shared concern for health. It reinterprets the Peckham Experiment’s holistic, preventative approach in the context of healthcare’s present and future, combining sport, community life, leisure and medicine, acknowledging health as not only an absence of illness but a consequence of all aspects of living.

Fig. 6.7 Xin Hao (Jerome) Ng Y3, ‘Peckham Hospice Care Home’. Situated in a Grade II listed building, the Hospice home provides care for people, enabling them to live the remainder of their lives to the full. Each unit offers views of the garden through the use of periscopes and movable façades and includes an additional room for family members.

Figs. 6.8 – 6.9 York Tsing (Nerissa) Yeung Y3, ‘Peckham Wellbeing Sports Centre’. Situated within the existing multi-storey carpark in Peckham, this project is an interpretation of the 1930s Peckham Experiment with additional cultural and recreation facilities. The building consists of transformable catalysts at varying scales which incrementally change this urban site into a vibrant centre for the community. Figs. 6.10 – 6.11 Lester Tian-Lang Cheung Y3, ‘Blind Community Centre’. The proposal aims to enrich the lives of the visually impaired by providing an environment for social integration and personal growth. The use of tactile surfaces and sound devices become the guiding principles to navigate through the building.