Design Anthology PG12

Architecture MArch (ARB/RIBA Part 2)

Compiled from Bartlett Summer Show Books

Architecture MArch (ARB/RIBA Part 2)

Compiled from Bartlett Summer Show Books

At The Bartlett School of Architecture, we have been publishing annual exhibition catalogues for each of our design-based programmes for more than a decade. These catalogues, amounting to thousands of pages, illustrate the best of our students’ extraordinary work. Our Design Anthology series brings together the annual catalogue pages for each of our renowned units, clusters, and labs, to give an overview of how their practice and research has evolved.

Throughout this time some teaching partnerships have remained constant, others have changed. Students have also progressed from one programme to another. Nevertheless, the way in which design is taught and explored at The Bartlett School of Architecture is in our DNA. Now with almost 50 units, clusters and labs in the school across our programmes, the Design Anthology series shows how we define, progress and reinvent our agendas and themes from year to year.

2024 Continuous Construction

Jonathan Hill, Elizabeth Dow, Barbara Campbell-Lange

2023 Architecture is a Time Traveller

Elizabeth Dow, Jonathan Hill

2022 Architect as Storyteller: Forest City

Elizabeth Dow, Jonathan Hill

2021 Rewilding London

Elizabeth Dow, Jonathan Hill

2020 Cultivating the Future and the Past

Elizabeth Dow, Jonathan Hill

2019 Designs on the Past, Present and Future

Elizabeth Dow, Jonathan Hill

2018 A City in a Building in a City

Elizabeth Dow, Jonathan Hill

2017 What is New?

Matthew Butcher, Jonathan Hill

2016 The Public Private House

Matthew Butcher, Elizabeth Dow, Jonathan Hill

2015 Occupying the City of London

Matthew Butcher, Elizabeth Dow, Jonathan Hill

2014 The Shock of the Old and the Shock of the New

Matthew Butcher, Elizabeth Dow, Jonathan Hill

2013 Factual Fictions

Matthew Butcher, Elizabeth Dow, Jonathan Hill

2012 A New Creative Myth

Matthew Butcher, Elizabeth Dow, Jonathan Hill

2011 Hybridisation and the Air and Industry of London

Matthew Butcher, Elizabeth Dow, Jonathan Hill

2010 Time, Motion, Energy

Matthew Butcher, Elizabeth Dow, Jonathan Hill

2009

Matthew Butcher, Elizabeth Dow, Jonathan Hill

2008 Hubbert Curve

Matthew Butcher, Elizabeth Dow, Jonathan Hill

2007 Making History

Elizabeth Dow, Jonathan Hill

2006 City within a City, the Independent Quarter

Elizabeth Dow, Jonathan Hill

2005 About Time

Elizabeth Dow, Jonathan Hill

2004 The Public Private House

Elizabeth Dow, Jonathan Hill

Jonathan Hill, Elizabeth

The climate has stimulated architectural, artistic and literary imaginations for centuries. In response to climate change and the need to creatively reuse scarce material resources and to consider how our buildings age, our premise this year is that buildings are always in continuous construction. Building sites often appear ruinous; excavation and demolition are essential to construction. Buildings are most fascinating when they are building sites, offering material, social, environmental, aesthetic and poetic potential. Rather than occurring in a linear sequence, PG12 has been considering how design, construction, maintenance, repair, ruin and demolition can occur simultaneously while a building is in use.

Our unit trip this year was to Venice, where we visited and were inspired by the 18th International Venice Architecture Biennale, ‘The Laboratory of the Future’, a theme which coupled decolonisation with decarbonisation. It was curated by Lesley Lokko, a graduate and a former tutor of PG12. Venice has been the site for many of the unit’s projects this year and has acted as an initial inspiration for others. We explored a certain irony in imagining the future in Venice, a city that is dominated by visions and narratives of its past and forecasts of its doomed future. By connecting the past, present and future, the PG12 students proposed varied, relevant and enjoyable design projects throughout the year. They designed buildings that thoughtfully explore the idea of continuous construction, with the ambition of providing their location with a new future – or even, new evolving futures.

We started the academic year with our dear friend and tutor, Professor Jonathan Hill, but tragically ended it without him. His guiding hand and indomitable spirit has nonetheless been with us along the way.

Year 4

Karolina Adamiec, Hoi Long (Adrian) Lai, Lok Yan (Ryan) Leung, Jordan Panayi, Anna Pang, Hanlin (Finn) Shi

Year 5

Maria Chiocci, Isobel Currie, James Hepper, Edwin Maliakkal, Alastair Manley, Heba Mohsen, Naomi Powell, Alice Shanahan, Jiayi (Silver) Wang, Yuen-Wah Williams

Design Realisation

Practice Tutor: James Hampton

Design Realisation

Structural Engineer: James Nevin

Thesis supervisors: Peter Bishop, Daniel Dream, Murray Fraser, Polly Gould, Jane Hall, Robin Wilson, Oliver Wilton

Critics: Kirsty Badenoch, Laurence Blackwell-Thale, Matthew Butcher, Nat Chard, Marjan Colletti, Sam Coulton, Max Dewdney, James Hampton, Luke Jones, Jan Kattein, Amy Kulper, Chee-Kit Lai, Constance Lau, Yeoryia Manolopoulou, Lesley McFagyen, Sophia Psarra, Rahesh Ram, David Shanks, Ro Spankie, Oliver Wilton

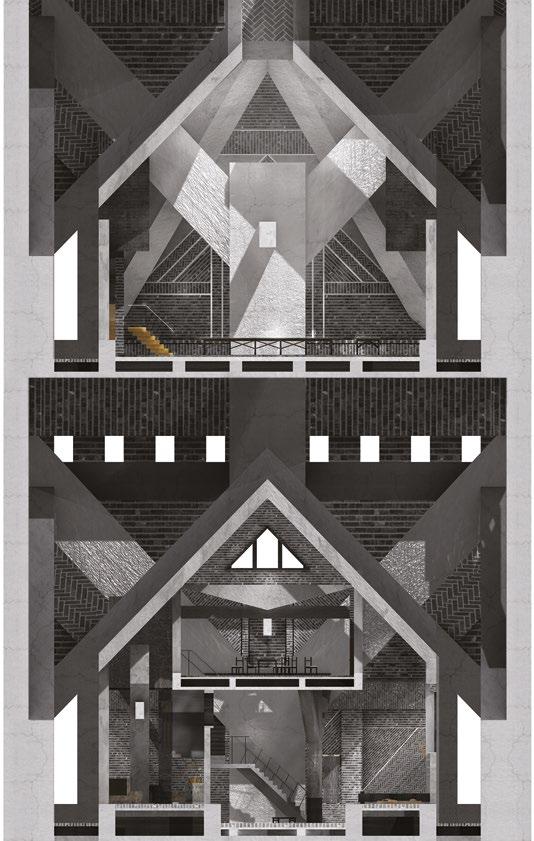

12.1 Jiayi (Silver) Wang, Y5 ‘The People’s Opera: Subdivision, Resistance, Resilience’. ‘Life as an opera’ is a profound cultural metaphor in China. This project evaluates the significance, evolution and meaning of Sichuan opera within an interdisciplinary context of art, collective memory, local mythology and history in Sichuan over generations. By proposing landscape theatres in both urban and rural Sichuan, the opera presents itself as a template that frames the daily practices and rituals of the people across the past, present and future.

12.2 Edwin Maliakkal, Y5 ‘The Story Untold’. Influenced by Adrian Forty’s The Art of Forgetting, this project records and narrates the culture and heritage of Fort Kochi in Kerala, India. Situated in a disused 18th-century warehouse, the architecture captures momentary glimpses of the city’s rich cultural narrative. It inspires a new approach to preserving and regenerating abandoned warehouses in Fort Kochi.

12.3, 12.5 James Hepper, Y5 ‘Taking Time: For an Island of Reciprocity’. Embedded in waste-dredged sediment, The School of Tresse Island stays with the trouble. By listening to the landscape and aligning the process of construction with the gradual accretion of sediments, it celebrates slowness in its shifting earthen spaces. Allying with phyto-remedial plants, colour blooms in ash glazes, revealing contamination as much as remediating it.

12.4, 12.7 Isobel Currie, Y5 ‘The Arctic Landscape Assembly’. This project is a reimagining of anthropocentric governance models emerging in the Arctic’s most vulnerable regions, enabling political actors to engage directly with the landscapes and communities they impact. The assembly aligns with the slow, unpredictable rhythms of the seasons and melting ice as parliamentary chambers stage, measure and remediate ecological dynamics across the landscape.

12.6 Lok Yan (Ryan) Leung, Y4 ‘The Venetian Compost Garden’. This memorial is a terramation necropolis that encapsulates the material transformation of human bodies into the ever-changing tidal landscape. The project proposes a new set of funerary rituals that work alongside the burial process of human composting, creating a collective living memorial that evolves with the tides. It redefines the distance and connection between the living and the departed.

12.8 Karolina Adamiec, Y4 ‘Teatro del Popolo’. This project is a theatre assembled by residents using waste materials produced by the Venice Biennale. It serves as temporary storage for the waste and creates a flexible space for the residents. It is also used for existing events and holiday celebrations. At the end of its lifespan, the materials are reused by the residents and become embedded in Venice.

12.9–12.10 Alice Shanahan, Y5 ‘A Gallery of Paint and C(aer)’. Through an atmospheric garden that caters to both people and architecture, this project is an act of care towards the overlooked constituents of architectural space. These include the caretakers who meticulously maintain and care for buildings, alongside the architectural surface and its treatment. The garden is defined by protection and enclosure, while gardening activities are a curatorial act of care.

12.11–12.12 Naomi Powell, Y5 ‘Piccola Scuola di Cinema: School of Composition’. In this polycentric film school, students are invited to imagine multiple futures for Venice. These consist of spaces ranging from the ephemeral to the more permanent, where filming and education are staged. They are intended to act as a catalyst for change while reframing the sustainability of the Venetian social fabric. Set design students construct follies and host a film festival, capturing an archive of its inhabitants and the city’s fading glory.

12.13 Jordan Panayi, Y4 ‘Theatre of Maintenance: An Act of Acqua Alta’. This project celebrates the slow process of a multigenerational stone construction. Acting in accordance with the good neighbour principle, the craftsmen of Venice Backstage supplement the proposed Biennale’s materials to aid in the management of high waters. In reciprocity with the maintenance of Venice, the local Venetians rebuild their diminished societal presence from its very foundations through the act of making.

12.14, 12.20 Yuen-Wah Williams , Y5 ‘Docklands Heronry’. Today Canary Wharf’s tenants are choosing not to renew their 25-year leases, and it is likely that their office blocks will become obsolete, forcing the Docklands into a second dereliction. This project is a fantastical redevelopment of Canary Wharf, focusing on several strategies for regeneration. It repairs the relationship between residents and the wharf, while also future-proofing it.

12.15 Hoi Long (Adrian) Lai, Y4 ‘Legacy of Neglect: Waste Paper Preservation’. This project explores overlooked elements in Venice, including the vanishing art of papercraft, abandoned islands and discarded waste. Drawing inspiration from the principles of bookbinding – protection, unification and restoration – the project intertwines the cultural and historic fabric with wastepaper architecture. It fosters a new community through the production and preservation of paper, celebrating the once-flourishing practice of papercraft.

12.16 Alastair Manley, Y5 ‘Burgess Park Peposo’. In this project, food and social infrastructure pieces are spread across strips of Burgess Park in South London. This helps alleviate the crises of food deprivation and loneliness in the city by enabling commensality (the social practice of eating together) while also promoting civic participation.

12.17, 12.19 Maria Chiocci, Y5 ‘Staging Nostalgia’. This project is an exploration of nostalgia, memory, identity and place. It reclaims Venice’s essence, offering solace to those estranged by the city’s transformation. Using two productions, cinema and theatre, it restores the identity of Venice through a transformative journey across time and scale. Both its function and structure are intricately scenographic and theatrical.

12.18, 12.21 Heba Mohsen, Y5 ‘Tuáth: A New Irish Corpus’. This project creates community-driven infrastructural solutions in rural Ireland by establishing alternative organisational structures. Focusing on autonomy with connection, its spaces enhance local knowledge and practices. Deterritorialising governance and merging oral histories and written policy, the project draws on the Irish language to find new relationships between rural and urban conditions, thinking and operating between Ireland’s split cultural identities.

12.22 Anna Pang, Y4 ‘The Tales of Liminality; Strands of Venetian Red’. This project revives the Scuola Grandi di Misericordia as a Venetian craft school, highlighting the endangered nature of velvet-weaving at Tessitura Luigi Bevilacqua. Past and present narratives are intertwined through structures of red silk to envision a place of productive liminality, teetering between the heritage of East and West.

Elizabeth Dow, Jonathan Hill

Elizabeth Dow, Jonathan Hill

Assembled from materials of diverse ages, from the newly formed to those centuries or millions of years old, and incorporating varied rates of transformation and decay, a building can curate the past, inform the present and imagine the future, transporting us simultaneously to many different times. The stones of a building belong to the geological time they were wrought, the time they were quarried, the time they were integrated into a construction site, the ever-progressing time of subsequent environmental change, and the varied times they are experienced. We may seem to travel back in time, even as architectural materials and components have literally travelled forward to meet us.

A building does not just exist in time: it creates time, travelling forward as a message to the future. However, there is nothing as old-fashioned as a past vision of the future. We have all experienced the sense that time has reversed. An era that seemed to be in the past becomes the future. In the 21st century the environmental catastrophe of 20th century agricultural overproduction now sees hedgerows replanted, industrial pesticides discarded and farms rewilded. The low tolerance of complex building systems sees thermal comfort reassessed and traditional technologies revived. This year students in PG12 have designed for a future time and place, and creatively considered their relations with both past and present. Flowing incessantly back and forth but never remaining the same, the river is a metaphor for the passage of time. We began the year at the strategic regeneration site of Gravesham Borough Council at the mouth of the Thames Estuary. For our field trip we studied past visions of the future and imagined future visions of the past in Edinburgh and Glasgow along the Forth and Clyde rivers. Students have subsequently designed a new civic architecture, in a time and place of their choice, with the ambition that their building is inventive and bold, considering both the need for longevity and the ability to anticipate and respond to change.

Year 4

Maria Chiocci, James Hepper, Edwin Maliakkal, Naomi Powell, Alice Shanahan, Jiayi (Silver) Wang, Yuen-Wah Williams

Year 5

Ted Bosy Maury, Xinhao Chen, Giorgios Christofi, Bryn Davies, Silvia Galofaro, Pierson Hopgood, James (Kai) McLaughlin, Kwan Yau (April) Soo, Joe Watton, Yunshu (Chloe) Ye

Technical tutors and consultants: James Hampton, James Nevin

Thesis supervisors: Camillo Boano, Eva Branscome, Murray Fraser, Sophia Psarra, Guang Yu Ren, David Rudlin, Robin Wilson, Fiona Zisch

Critics: Sabina Andron, Felicity Atekpe, Kirsty Badenoch, Sabina Blassiotti, Barbara-Ann Campbell-Lange, Ana Monrabal-Cook, Penelope Haralambidou, Jan Kattein, Constance Lau, Elliot Nash, Rahesh Ram, Tom Reynolds, Isaac Nanabeyin Simpson, Dom Walker, Tim Waterman, Alessandro Zambelli

12.1 Giorgos Christofi, Y5 ’Aphrodism: (Re)forming Cypriot Heritage, The Parliament of Social Affairs’. The project assesses the Cypriot buffer zone as an infrastructure of segregation between the two communities inhabiting the island. The project proposes transforming the buffer zone into a social affairs parliament, resolving frictions and promoting symbiosis between Turkish Cypriots and Greek Cypriots by enforcing a cultural merger through the cultivation of the Cypriot landscape.

12.2 Kwan Yau (April) Soo, Y5 ‘Architecture as the Guardian of Collective Memory’. Swimming is a seemingly innocent and mundane activity that is familiar yet cleverly allows for the congregation of people. The project takes the approach of being apolitically political and proposes peaceful collaboration to build an urban pool. It engages with significant buildings and explores previously unconsidered ways of interacting with water.

12.3 Alice Shanahan, Y4 ‘Playing Politics: A People’s Parliament’. The North Yorkshire coastline is being pushed to breaking point: environmentally, socially and politically. Realised through political, material and seasonal transitional timelines, the architecture responds accordingly. Community and the need for radical change are re-embedded into the landscape, redefining connections between land, sea and people.

12.4 James Hepper, Y4 ‘Building [Dwelling]: The Slow Build’. In the era of the instant, this project looks instead to wider timescales: tidal rhythms, seasonal cycles and the gradual accretion of the salt marsh. In the postindustrial waterfront of Gravesend, The School of Earthworks and Ecology celebrates slowness in its shifting, slip-cast spaces and remedial planting strategies.

12.5 Edwin Maliakkal, Y4 ‘An Architectural Palimpsest’. Mumbai has a remarkable history interwoven with the textile industry and its mills, many of which are now derelict. The proposal aims to capture the essence of Mumbai, demonstrating an admiration for its identity and cultural heritage. In doing so it evokes a sense of familiarity by encouraging memories of Mumbai to be inscribed and erased over time.

12.6 James (Kai) McLaughlin, Y5 ‘A Paper Architecture for Messy Hybrids’. The project tackles the fixed understanding of hybridity, investigating different types of cultural intersection and their manifestations. A squatting Paper School in the former Imperial Paper Mill becomes a site for messy, diverse identity production, usurping the imperialistic provenance of the mill. Paper’s material capacity is expanded to serve the processes of learning, testing, negotiating, building and rebuilding in a dialogue of collective cultural production.

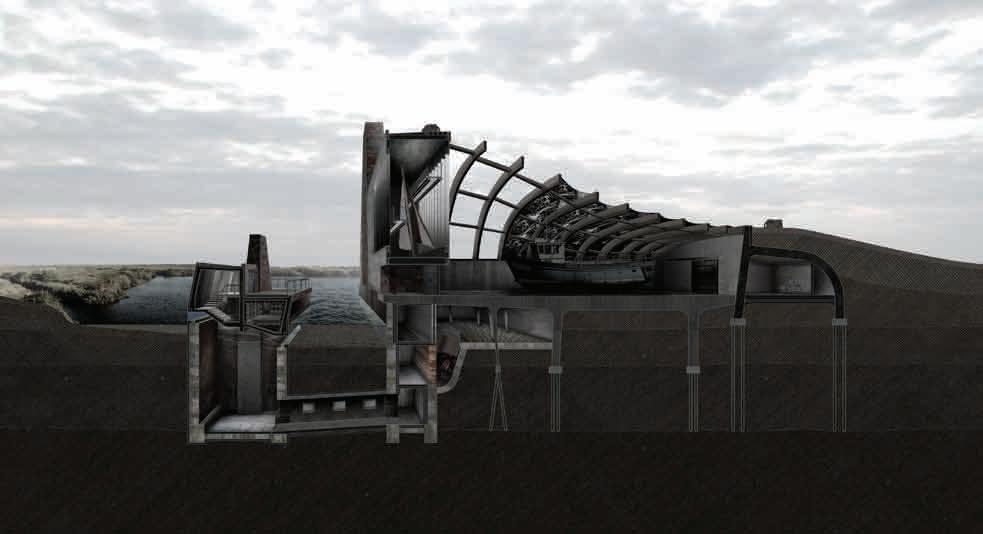

12.7–12.8 Silvia Galofaro, Y5 ‘The Mud Dredger: Muddy Waters and the Unloved Spolia’. The proposal challenges the forgotten relationship between the City of London and the River Thames. A mud-dredging building is proposed that carefully selects and curates the river’s leftovers. The building contributes to improving the river’s health by simultaneously reconnecting the city to some of its lost or overlooked accounts.

12.9 Yuen-Wah Williams, Y4 ‘Coalhouse, Stiltbury: A Collaged Architecture’. Severe weather anticipated as a result of climate change means that much of Tilbury, Essex is at risk of flooding. This project collages together local architectures that are vulnerable to flooding and raises them on a reclaimed steel frame that sits over Coalhouse Fort. Tilbury’s large unemployed population will be offered the opportunity to retrain and learn construction trades to form the workforce that will carry out the project.

12.10 Naomi Powell, Y4 ‘Regenerating the Hoo: Creating a Symbiotic Relationship with the Thames Estuary’. Taking the stance that we must learn to live with flooding, climate

researchers and citizen scientists act as guardians of the river, establishing a hybridised wetlands centre. Through the cultivation of oysters and seagrass, and the harnessing and amplification of natural regenerative processes they learn and share vernacular construction skills to create an architecture designed to deteriorate.

12.11 Maria Chiocci, Y4 ‘Monumental Arcadia’. Based in Rousham House and Gardens, the project considers the construction of a monumental arcadia – a poeticshaped space associated with natural splendour in which animals and humans live in harmony. The proposal uses a scenographic approach to encourage moments of rest and contemplation, creating an architecture of Otium

12.12 Jiayi (Silver) Wang, Y4 ‘In the Presence of Absence’. Within their absence lies a reminder of the former prosperity of the River Thames’ downstream towns and the artistic finesse of Chinese artistic techniques. Inspired by the journey of a museum conservator, the project’s design unveils a silk painting restoration, transforming this hidden craftsmanship into a performance for all.

12.13 Ted Bosy Maury, Y5 ‘A Cornish Pixie: Reading the Witches of Boscastle’. The project embodies the theatricality of tarot readings. This is realised through performing a ‘reading’ of the North Cornish site of Boscastle; its attendant climate-precarity, history of salvage and magic, coastal liminality; and the collection of the existing Museum of Witchcraft and Magic.

12.14 Bryn Davies, Y5 ‘The Metamorphosis of St Luke’s: Resplendence, Ruination, Renaissance’. The project charts the inhabitation of St Luke’s Gravesend from its 1960s inception as a non-denominational place of worship on the banks of the Thames, through a steep period of decline and ruination due to dwindling passenger numbers, to its current day renaissance as a new school of fine art.

12.15 Pierson Hopgood, Y5 ‘White Mountain College: A Research and Rehearsal Library for the Dyslexic Arts’. This project imagines a Library for the Dyslexic Arts set in 1960s Ash, Kent. The library is an educational facility for painting, sculpture and architecture that utilises dyslexic thinking to further the art world and to drive research. The library’s collection continually evolves creating a dynamic interplay between artworks and architecture.

12.16–12.18 Xinhao Chen, Y5 ‘House of Spirits’. The project reflects on worship and ritual, questioning how spirits and the living might interact without the involvement of religion. Proposing an alternative worship ritual, centred on the harvest of sorghum, a set of built forms for human occupation are proposed, dedicated to the spirits of Dachuan, China.

12.19 Joe Watton, Y5 ‘Cliffe Fort: An Adaptable Monument’. The project imagines an alternative history for Cliffe Fort, an abandoned Victorian military site near Gravesend. Questioning Silkin’s post-war rehousing programme, the site is reappropriated as an experimental ninth new town for the capital; built interventions serve as monuments to the longlost qualities of life in the slums of wartime London.

Elizabeth Dow, Jonathan Hill

Elizabeth Dow, Jonathan Hill

We expect a story to be written in words, but it can also be delineated in drawing, cast in concrete or sown in soil. Such tales have special significance when they resonate back and forth between private inspiration and public narrative. Conceiving the architect as a storyteller places architecture at the centre of cultural production, stimulating ideas, strategies and emotions. Exceptional architects are also exceptional storytellers.

While a prospect of the future is implicit in many novels, it is explicit in many designs. Some architects conceive for the present; others imagine for a mythical past, while yet others design for a future time and place. Alternatively, an architect can envisage all three in a single structure. To understand what is new, we need to consider the present, the past and the future: we need to think historically. Our concern is the relevance of the past – recent or distant – to the present and future, even as we speculate on the question: how and why might this happen now?

As well as history in its broader sense, we are interested in personal history. PG12 encourages students to develop a personal collection of ideas, values and techniques that reflects their unique outlook.

Our project brief for the year was the Forest City. We considered the city as a place of nature and growth, and the forest as a state that connects air to earth, climate to geology. We observed how each forest, city or building is a complex ecosystem, teeming with creatures and subject to their rhythms, intertwined in a network of relations with other life forms, including humanity.

The Forest City, being analogous to an ever-changing ecosystem, should be more temporally aware than other architectures. It requires constant re-evaluation, encouraging and questioning the creative relations between objects, spaces and occupants at varied dimensions, scales and times. Multiple iterations of the Forest City were designed and redesigned, both literally and allegorically. With the forest journey acting as a metaphor of the imagination, each project was founded upon the stories that students conceived, the research that they undertook and the architectural languages that they developed and honed across the year.

Year 4

Theodosia (Ted) BosyMaury, Giorgos Christofi, Silvia Galoforo, Pierson Hopgood, James (Kai) McLaughlin, Joe Watton

Year 5

Caitlin Davies, Lola Haines, Theodore Lawless Jones, Jaqlin Lyon, Sijie Lyu, James Robinson, Felix Sagar, Gabrielle Wellon, Tianzhou Yang, Yunshu (Chloe) Ye

Technical tutors and consultants: James Hampton, Chloe Hurley, James Nevin

Thesis supervisors: Gillian Darley, Stephen Gage, Christophe Gérard, Stelios Giamarelos, Polly Gould, Elise Hunchuck, Thomas Pearce, Guang Yu Ren, Oliver Wilton, Stamatios Zografos

Critics: Alessandro Ayuso, David Buck, Carolyn Butterworth, Barbara-Ann Campbell-Lange, Kate Cheyne, James Hampton, Penelope Haralambidou, Jessica In, Chee-Kit Lai, Constance Lau, Thandi Loewenson, Artemis Papachristou, Barbara Penner, Rahesh Ram, Elin Söderberg, Jonathan Tyrrell, María Venegas Raba, Dominic Walker, Dan Wilkinson, Fiona Zisch

12.1 James Robinson, Y5 ‘Martian Migrators: The Non-Essential Essentials of Thriving on Mars’. The project examines how humans might flourish on Mars. The notion of thriving is explored through the development and success of humans and architecture in the inhospitable environment of Mars. Components of Martian thriving are questioned through individual and large-scale studies.

12.2, 12.3 Caitlin Davies, Y5 ‘For Peat’s Sake: A DEFRA Institute of Agricultural & Architectural Research’. Proposed as the new seventh division of the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (DEFRA), the institute acts as a site where agricultural and architectural research can be developed in tandem. By moving government offices to the remote peat bogs of the Yorkshire Dales, the project reframes nature as the building’s primary occupant and explores how architecture can be an active participant in the conservation of these damaged landscapes.

12.4, 12.5 Tianzhou Yang, Y5 ‘A Sanctuary for Chinese Calligraphy in the Desert’. This project explores ways to preserve the art of calligraphy and its spirit of independence in an ever-changing political and cultural environment. Located in the harsh environment of the Gobi Desert in north-west China, the sanctuary is far from the political and urban madding crowd, in the hope that unwanted hands are kept away from the masterpieces of calligraphy. The centre allows calligraphers to study these masterpieces in peace, so that recognisable versions can continually contribute to the preservation of cultural heritage.

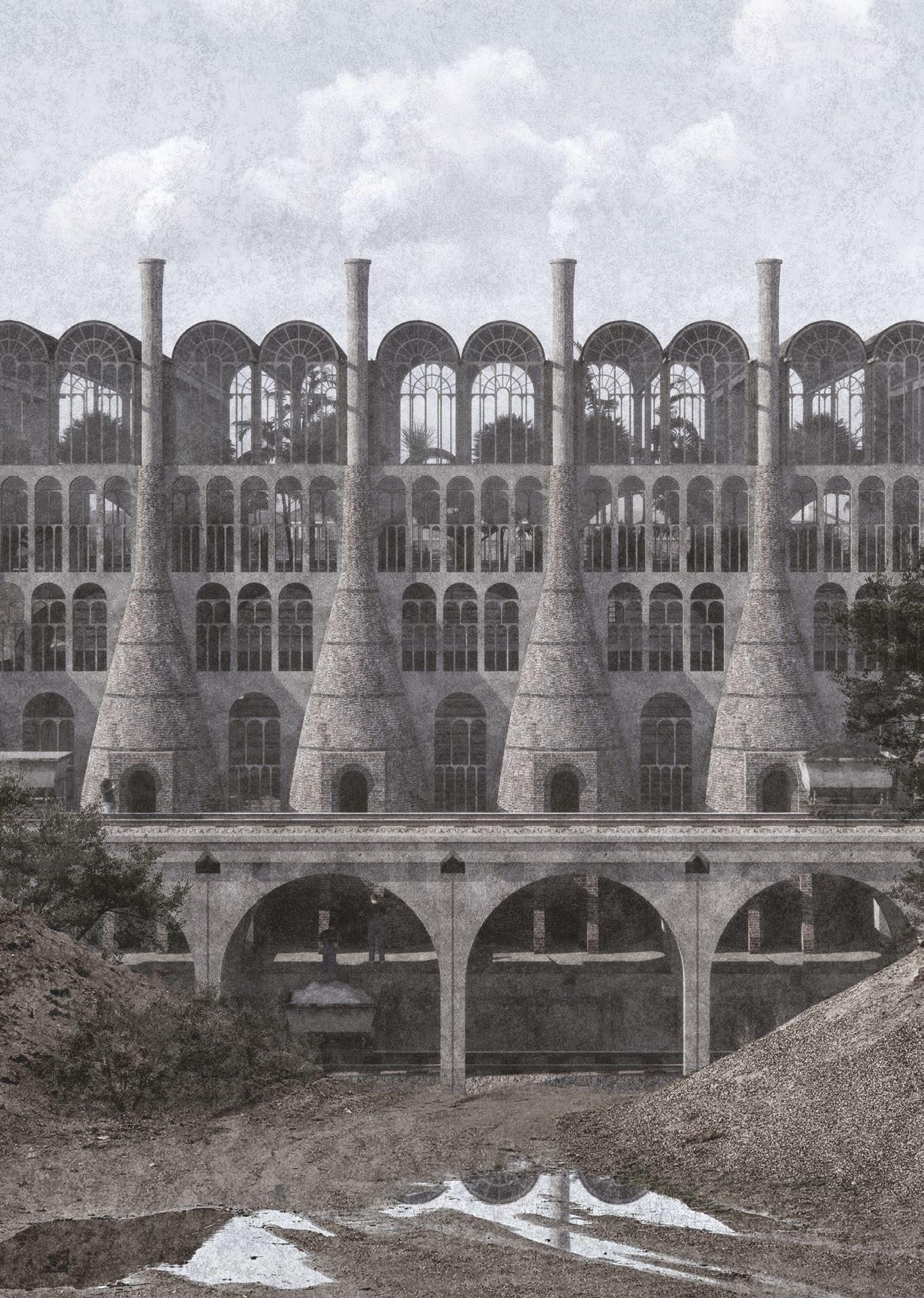

12.6, 12.7 Felix Sagar, Y5 ‘The Chalk Works: Chalk-Based Renovation, Remediation and Regeneration’. Through establishing wider systems of material industrial symbiosis and methods of tailored chalk-based renovation, this project proposes the use of waste chalk ‘filter cake’ to renovate, remediate and regenerate the derelict Shoreham Cement Works, converting it into a ‘Chalk Works’ – a construction school which offers an alternative material-driven curriculum.

12.8 James (Kai) McLaughlin, Y4 ‘Staging Liminality’. The project explores ways in which effective cultural hybridisation can mobilise direct forms of productive ecological and societal change. It proposes the construction of a Japanese Noh theatre on the site of a recently demolished lighthouse on the shingle spit of Orford Ness. The scheme uses reconstruction as a ritually resilient practice to act alongside this dynamic landscape of coastal erosion. These rituals of construction are superimposed onto a wider shingle restoration scheme, blurring the boundaries between performance, restoration, participation and construction.

12.9–12.11 Lola Haines, Y5 ‘A Debate in the Dark’. How can we have more accessible ways of seeing and sharing our riverscapes? This project provides an alternative way of engaging with our riverscapes. An eco-political initiative of dark sky river corridors addresses distinct yet overlapping subjects: water and light pollution, climate change and flooding, and social and economic migration.

12.12 Jaqlin Lyon, Y5 ‘Cold Comforts and Savoury Air: A Hospital for Bodies and Buildings’. Through the dialectic of illness and repair, the project explores notions of care at the scales of body and building. Treating an array of illnesses which at times overlap in surreal and theatrical operations, the hospital conflates past, present and future narratives within the crumbling city of Kiruna in northern Sweden.

12.13, 12.15 Theodore Lawless Jones , Y5 ‘A Weird Pub in the Middle of Nowhere’. Bizarre carvings on the King Stone monolith on Stanton Moor posit a pictorial and literary conundrum in which Charles Dickens’s imaginary

realm enters the actual. Both the real and fictitious worlds exist as vignettes in an inverted presentation of the mundane to deliver a body of junctures and phenomena celebrating the mystery.

12.14 Joe Watton, Y4 ‘Of Sheep, Stone & Hedgerows’. The project responds to the recent developer-led expansion of Axminster, a historic agricultural market town in East Devon. The current masterplan is used as a testbed to develop a more socially and ecologically responsive vernacular derived from the centuries-old network of Devon hedgerows which currently occupy the site.

12.16–12.18 Sijie Lyu, Y5 ‘Getting Lost in the Woods’. We are obsessed with the undistorted quality of glass but overlook its magical potential. The project challenges the limited range of applications glass is currently afforded within the built environment. Material choices in the proposal often counter building conventions, demonstrating the performative and theatrical side to a new architecture located in the Black Forest, Germany.

12.19 Giorgos Christofi, Y4 ‘Re-Fertilising Gaia’. The Temple of Gaia (goddess of the Earth) is located between the city of Kalambaka and the Meteora forest in Greece. The Ancient Greek ritual of Thesmophoria is revived in the temple in an effort to encourage the regrowth of the forest in exchange for human fertility.

12.20 Pierson Hopgood, Y4 ‘Lore of the Land’. The New Epping Commune, an evolving school of craft and construction, explores the long-lasting metaphorical connection between storytelling and craft. The project focuses on the importance of using one’s hands and building a deeper spiritual connection with the process of making.

12.21 Theodosia (Ted) Bosy Maury, Y4 ‘Spinning Ruins’. This is an alternative history in which the Crescent Wool Warehouse in Wapping is adapted and added to by two artists in alternation. Over the course of several decades, the pair make an accretive theatre, constructed of salvaged materials, castings, rubble aggregates and wool, which filters and stores storm surge water.

12.22 Silvia Galofaro, Y4 ‘San Siro: Destroying and (Re)building an Icon’. The project reimagines the iconic San Siro Stadium in Milan, scheduled for demolition in 2026, by reanalysing the contemporary notion of iconoclasm. By referencing the Duomo Cathedral of Milan and the Veneranda Fabbrica del Duomo guild, the project explores the process of reverse quarrying through the Roman technique of spolia

12.23 Gabrielle Wellon, Y5 ‘Freedom to Roam’. The project presents a proposal for a more progressive right to roam in England that encourages greater inclusivity and access to open space. By extending the right to a wider variety of landscapes and designated openaccess buildings, the proposal intends to encourage roaming, both internally and externally. Situated in the context of Wiltshire’s private estates, the constructed spatial narrative is based on the allegorical Wiltshire ‘everywoman’, Ruby.

Elizabeth Dow, Jonathan Hill

Elizabeth Dow, Jonathan Hill

Exceptional architects are exceptional storytellers. Such tales have special significance when they resonate back-and-forth between private inspiration and public narrative. When everybody else is looking at one time and place, it is always good to look elsewhere as a discovery may be yours alone, and thus more surprising.

In PG12, we learn from the past and stimulate radical solutions for the future. Our project this year was ‘Rewilding London’, from which new architectures, landscapes, ways of living and cities emerged. The source of inspiration might be a person, place or event. Equally, it could be a construction technique or material language. The inevitability of change – whether of climate, ethics or architecture – requires us to utilise it, notably as a design may take years to complete. Conceiving design, construction, maintenance and ruination as simultaneous ongoing processes that occur while a building is occupied, we encourage designs that are drawn in multiple times and states. Assembled from materials of diverse ages, from the newly formed to centuries or millennia old, and incorporating varied rates of transformation and decay, a building is a time machine that curates the past and imagines the future.

The last ten years have witnessed significant changes that will influence our education, jobs and national identities: the 2008 worldwide financial crash, 2016 Brexit vote and the target for net-zero carbon emissions by 2050. Furthermore, 2020 and 2021 were momentous years as a result of the Covid-19 pandemic.

Ideas about climate change express wider societal values, including attitudes to nature, governance and design. The dangers of global warming are real and need to be addressed when and where possible, notably because their effects are unequal, often causing greater harm to disadvantaged communities. Awareness of climate change may also encourage cultural, social and environmental innovations and benefits, whether at a local, regional or global scale, stimulating more thoughtful and exciting designs. Architects must have the courage to ask awkward questions. We need to look deeper into the past and further into the future.

Rewilding usually entails transforming land into a self-conserving system with minimal human intervention, but the term has greater relevance when it is applied to the urban as well as the rural. It is understood as a means to acknowledge the interdependent coproduction of the human and non-human in all aspects of a shared Earth.

Year 4

Caitlin Davies, Lola Haines, Theodore Lawless Jones, Jaqlin Lyon, James Robinson, Felix Sagar, Gabrielle Wellon, Tianzhou Yang

Year 5

Sabina Blasiotti, James Bradford, Jean-Baptiste Gilles, Elliot Nash, Callum Rae, Arinjoy Sen, Benjamin Sykes-Thompson, Chuxiao Wang, Yunshu (Chloe) Ye

Technical tutors and consultants: James Hampton, James Nevin

Thesis supervisors: Alesandro Ayuso, Edward Denison, Murray Fraser, Daisy Froud, Stelios Giamarelos, Elise Hunchuck, Zoe Laughlin, Tania Sengupta, Iulia Statica

Critics: Kirsty Badenoch, Carolyn Butterworth, Blanche Cameron, Barbara-Ann CampbellLange, Adrian Hawker, Jan Kattein, Toni Kauppila, Constance Lau, Igor Marjanovic, Jason O’Shaughnessy, Franco Pisani, David Shanks, Tim Waterman, Alex Zambelli, Fiona Zisch

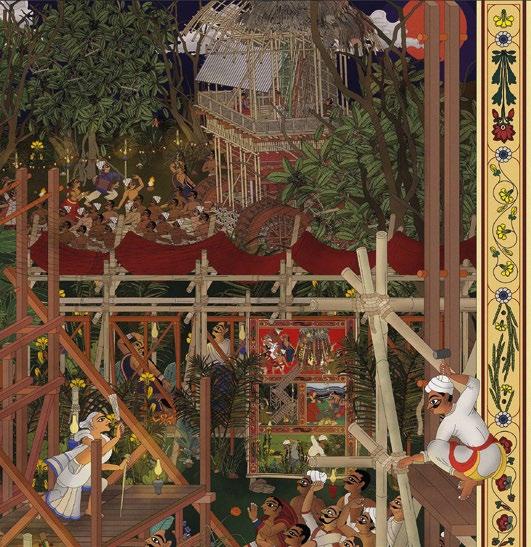

12.1 Callum Rae, Y5 ‘The Olive Morris Institute for Drawing, Building and Squatting’. The project provides an alternate proposal for the site formerly occupied by Olive Morris House: the Lambeth Council housing office in Brixton and named after the housing activist Olive Morris. The proposal is a new educational institution that teaches hand-drawing and construction skills as constituent parts of an architectural education that combine in the embodied act of squatting. 12.2–12.4 Arinjoy Sen, Y5 ‘Rituals of Resistance: Narratives of critical inhabitation’. The project addresses the contested inhabitation of fragile ecosystems in the Sundarbans, situated in the borderlands of Bangladesh and India. It proposes a self-sustained productive settlement that fosters a construction of spatial identity, while elevating the significance of indigenous land stewardship. Additionally, the settlement seeks to increase the ritual narrative practices of marginalised and hybridised identities, as a means to resist erasure, through the apparatus of a travelling theatre.

12.5 Jean-Baptiste Gilles, Y5 ‘The Bricks, the Stucco and the Air’. Before we can propose a less-damaging way of living in which isolation of the building is reduced, air must be considered as an architectural material. The project is a series of bedrooms for guests of the Royal Institution. An architecture is created that can be appreciated through the bricks, stucco and the air.

12.6–12.8 Chuxiao Wang , Y5 ‘Lost in London’. The project is an enigmatic book describing the lives of monsters in London. The monsters struggle to adapt to city life and carry out their purpose of freeing the ravens in the Tower of London. By telling their stories and experiences, the book explores a non-anthropocentric city life involving history, mythology, legend and literature, interweaving the real with the unreal and history with the future.

12.9 Jaqlin Lyon, Y4 ‘The Embassy for Dirty Things, Messy Ideas & Unfinished Endeavours’. Dirt denotes difference; using its power to disrupt, the project proposes a reconfiguration of cultural attitudes, bureaucratic order and objective values. Exploring the transgressive potential of programmatic hybrids and formal paradoxes to overcome binaries within social, cultural and political operations, the Embassy combines a laundromat, debate chamber and printing press in London’s bureaucratic district. This creates space for public exchange in the margins of hegemonic structures.

12.10 Felix Sagar, Y4 ‘The Aldgate Chalkland School of Special Scientific Interest’. The proposal explores wilding the un-wild city child using chalk as a ‘bonding material’. By using atmospheric phenomena, human and non-human occupants establish new urban dialogues. The project explores how an existing building and curriculum might be altered to support a wild and non-didactic learning model. Inspired by biological mutualism, the method links the process of play to biological and geological cycles that create new learning landscapes.

12.11 Lola Haines, Y4 ‘A Theatre for ‘Lesser’ Creatures’. The theatre addresses urban society’s disconnect with nature. Learning from and giving agency to the environment creates a dialogue of exchange with humans. The theatre’s function is linked to natural and seasonal events, like insect migration and behaviour, to stimulate greater change across the city. As insects disperse pollen, a wandering theatre festival seeds the ground for future growth.

12.12–12.14 Sabina Blasiotti, Y5 ‘The Village Inside the Nuclear Power Plant’. The design narrates the future of a decommissioned nuclear power plant and the surrounding village Mihama in Japan. The narrative generates and is generated by an interminable dialogue between nuclear forms and heritage, recycled nuclear

waste and traditional customs in the coastal town. This dialectic is further reflected in the construction of a Shinto sanctuary, integrating ceremonial and commercial activities such as fishing, rice farming and sake brewing.

12.15 Benjamin Sykes-Thompson, Y5 ‘Barking Sands & Borough Bells: The London sound authority’. The project is informed by Japanese sound culture that does not resonate with architectural acoustics and reintroduces the overlapping aural communities that once made up London’s population. Architecturally, spaces mimic the aural spaces of old Whitehall – areas of rumour, declamation and democratic ‘transparency’ – while also exploring the phantom sounds that exist between ourselves and the perceived built environment.

12.16–12.17 Theodore Lawless Jones, Y4 ‘The New HM Liberty of the Clink’. A contrived shimmering neon microclimate, where darkness reveals lost rhythms in sedentary human existences, stimulates behaviour to rewild London. Condemned prisoners, guilty of environmental wrongdoing by the Court of the Clink, lead a primitive existence in their communal and autonomous garden complex. The objectives are personal desistance, the empowerment of synanthropic birds within their delicate urban-ecosystem and the consequent realisation of mutual fulfilment and natural affinity.

12.18 James Robinson, Y4 ‘Martian Miners of Portland’. Having settled on Mars for the past 30 years, the first Martian miners have come back to Earth. Residing on the Isle of Portland, Dorset, within the Coombefield Quarry, the practice of a New Stone Age is formed. Fabricated from the history of Portland and future Martian regolith mines, the Portland-Martian vernacular is created.

12.19 Tianzhou Yang , Y4 ‘Ode to Life: A natural process’. This project is designed for gradual and pain-soothing organic burials where both fallen leaves and deceased human bodies integrate with nature to nurture new life. Fallen leaves are collected and memorialised through the construction and reconstruction of the cemetery. Human bodies are composted to further contribute to the prosperity of plants, accentuating that life is not linear but circular.

12.20 Caitlin Davies, Y4 ‘The Worshipful Company of Dismantlers’. The 111th guild within the City of London promotes the reuse of the city’s architecture through the act of dismantling and remantling. The new guild reflects the role the built environment plays within the environmental crisis and how we might change the practices and reasons for building as we do.

12.21 Gabrielle Wellon, Y4 ‘News from Nowhere’. Rendering the fantastical commons-based world of cooperation, sketched out by William Morris in his utopian novel News from Nowhere, or, an Epoch of Rest (1890), the project proposes a community in Gospel Oak, London, that is self-governed, managed and developed by the residents. Morris’ conceptualisation still retains the potential to stimulate a democratic dialogue between work, art, nature and society.

12.22 Elliot Nash, Y5 ‘Forgetting Whitehall; Casting Blackhall’. The project proposes a building that subverts methods of physical and non-physical preservation, to fold time through Whitehall in pursuit of a kind of rewilded London. It moves through themes of redaction and transience, and the idea of the counter monument to arrive at an architecture that challenges contemporary thought and practice around conservation.

Elizabeth Dow, Jonathan Hill

Elizabeth Dow, Jonathan Hill

A building can be designed for the present, in response to contemporary contexts, needs and desires. A design can be a selective, critical and creative response to the past. Equally, a prospect of the future can be implicit in a design, which is always imagined before it is built and may take years to complete. Some architects conceive a design for the present, some imagine for a mythical past, while others design for a future time and place. Alternatively, an architect can envisage the past, the present and the future in a single architecture.

Architectural time incorporates design, construction, use, maintenance and ruin. Rather than a temporal sequence, each stage can occur simultaneously. Demolition is essential to construction and building sites often appear ruinous. Ruination does not only occur once a building is without a function: it is a continuous process that develops at differing speeds in differing spaces while a building is constructed and occupied. Assembled from materials of diverse ages, from the newly formed to those centuries or millions of years old, a building incorporates varied rates and states of transformation and decay.

Our increasing appreciation of sustainability and limited resources can lead us to recognise that maintenance might be where some of the most impressive and challenging innovations are found. Fluctuating according to the needs of specific spaces and components, maintenance and repair may delay ruination, while accepting and accommodating partial ruination can question the recurring cycles of production, obsolescence and waste that feed consumption in a capitalist society.

The inevitability of change – whether of use, climate, or governance – requires us to consider the future as well as the present. How should a building react to climate change when, for example, it is predicted that London will have the climate of Barcelona by 2050? How long should a building last? 100 years? 200 years? 1000 years? In response to anthropogenic climate change and in support of sustainable development, we propose that buildings should be designed to endure and adapt, emphasising longevity not obsolescence. Construction, maintenance and ruination are conceived as simultaneous and ongoing processes. Our designs are drawn in varied times and states.

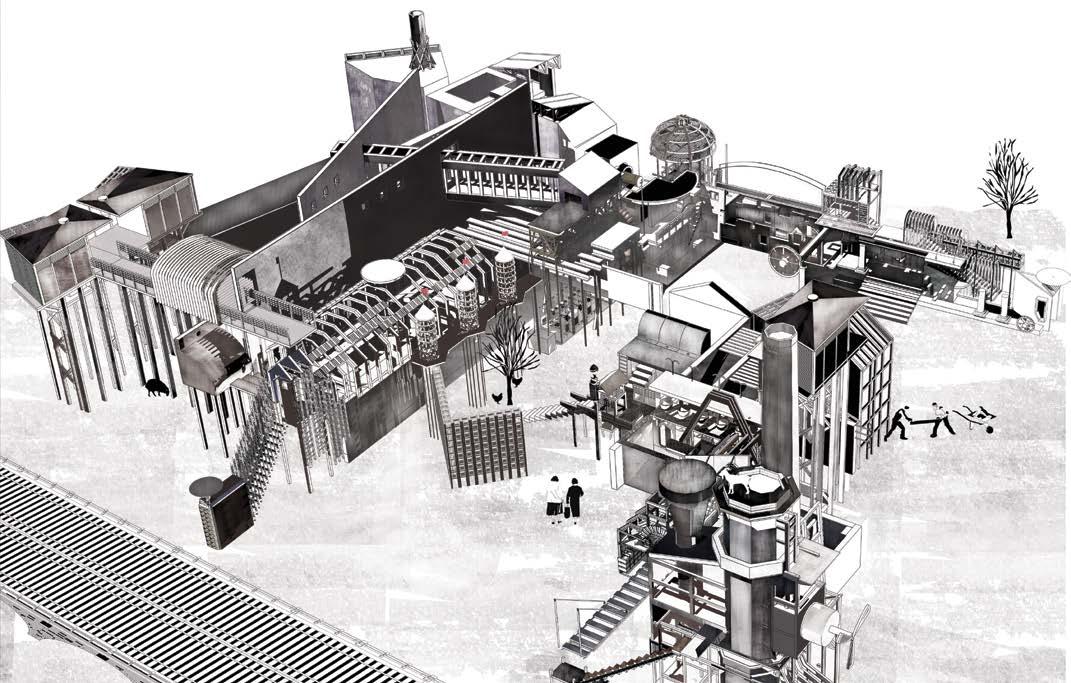

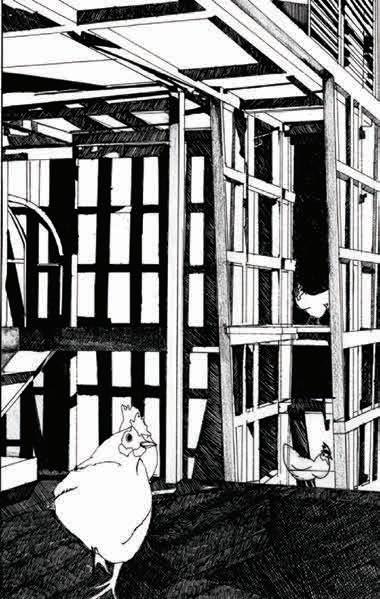

In PG12 this year, the farm is a metaphor for a design project. Combining construction and maintenance, growth and decay, a farm is always specific to the qualities of a place – its climate, topography, material and social conditions – and what is best cultivated there, whether that is food, wind, stories, health, architecture, community or ideas. A farm can build upon its past and cultivate the future.

Year 5

Amelia Black, Jonathon Howard, Laura Keay, Przemyslaw Rylko, Isaac Simpson, Serhan Ahmet Tekbas

Year 4

Sabina Blasiotti, James Bradford, Jean-Baptiste Gilles, Elliot Nash, Callum Rae, Arinjoy Sen, Aryan Tehrani, Benjamin Sykes-Thompson, Chuxiao Wang, Yunshu (Chloe) Ye

Thank you to our Design Realisation tutor James Hampton and structural consultant James Nevin

Thesis supervisors: Stylianos Giamarelos, Anne Hultzsch, Sophia Psarra, Tania Sengupta, Oliver Wilton

Thank you to our critics Alessandro Ayuso, Barbara-Ann CampbellLange, Ben Clement, Sam Coulton, Sebastian de la Cour, Stelios Giamarelos, Mary Vaughan Johnson, Jan Kattein, Perry Kulper, Constance Lau, Igor Marjanovic, Ganit Mayslits Kassif, Mario Pilla, Elin Soderberg, Eva Sopeoglou, Sumayya Vally, Dominic Walker, Izabela Wieczorek

12.1 Isaac Simpson, Y5 ‘An Architecture Between Cultures: the Highland Council’. This project is an imagination of the African gaze mapped onto the British landscape. The project’s ambition is to challenge existing landownership boundaries by constructing a ‘radical’ vessel that roams across the Scottish Highlands, rehabilitating the land and cultivating conversations in a way that requires communities’ cultural diversity and appreciation.

12.2 Amelia Black, Y5 ‘St Just State’. The landscape of Land’s End was forever changed by the human endeavour to extract tin and copper from the earth. St Just State is a micro-nation striving to re-industrialise, rejuvenate and re-establish the local economy. A new vernacular of industrial buildings reclaim the tin mines of a now deprived area of West Cornwall. Sculpted from the landscape, they are constructed by the community that inhabit them. Forever evolving, St Just State not only produces goods, but a skilled construction workforce.

12.3–12.4 Laura Keay, Y5 ‘The New English Rural’. This project is essentially the development of a code for living that proposes new and/or refined approaches to how we might construct a rural architecture, and how we might reuse and repair. This is applied to a somewhat counter-intuitive testbed site to what we might judge to be rural – a brownfield site in Rochester, that is struggling both socially and economically. The main outcome deals with the issues of unemployment, education and income, exploring whether a rural life can contribute to an urban community’s wellbeing and future development.

12.5 James Bradford, Y4 ‘Westminster Arboretum’. The Westminster Arboretum is an architectural response to the threat of global warming, seeking to protect native British species of tree from extinction. Constructed and grown from the trees themselves using traditional horticultural methods, the project suggests a necessity that cities must adopt a hybrid between an architectural and a reforested landscape.

12.6 Yunshu (Chloe) Ye, Y4 ‘Operation Hide and Seek: The Ministry of (Anti)-surveillance’. As the UK hurtles towards a surveillance state during the Covid-19 crisis, this project seeks to create an anti-surveillance government body that is ‘hidden in plain sight’ by being temporarily ‘blinded’, ‘muted’, or ‘deafened’ with the help of a series of playful mechanisms inspired by children’s games.

12.7 Chuxiao Wang, Y4 ‘The Rebirth of Peng’. All things have spirits. This project narates a space as a living creature, recalling a spiritual connection among monster (shelters), nature (the local environment) and mankind (users). Born as a half-fish half-bird monster, ‘Peng’ uses its talent to guide the poet to sense the wind, creating an intimate dialogue between the poet and nature. This bond evokes the poetry of life.

12.8 Callum Rae, Y4 ‘The House They Left Behind’. Consisting of a public house, a town hall and a private residence, this project is a reassertion of the political and social qualities of publicly owned social spaces and a reimagining of Victorian bar spaces and thresholds.

12.9 Sabina Blasiotti, Y4 ‘The Death, the Vine and the Soil’. This project introduces a human composting facility and biodynamic winery in the abandoned island of Poveglia in the Venetian lagoon. Poised between the notion of the ‘terroir’, phenomenology and Gothic architecture, the design rises from the ground where it will return in the fullness of time.

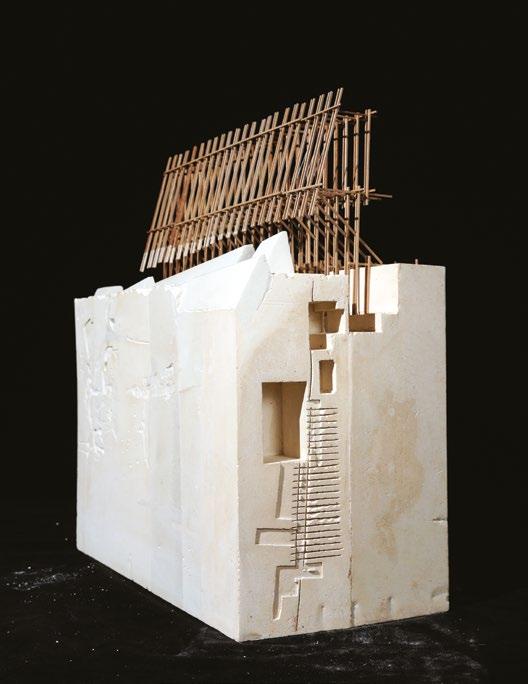

12.10–12.12 Jonathon Howard, Y5 ‘A Liminal Place: the (Re)construction of Kilmahew’. This project considers the role of the architect and archaeologist in uncovering the peculiar past, present and future of St Peter’s Cardross, Scotland. Students of a hybrid school of architecture and archaeology propose and test new forms of construction

through the reconstruction of the forgotten Kilmahew house, exercising tectonic, archaeological and architectural palimpsest.

12.13 Serhan Ahmet Tekbas, Y5 ‘The Ruins of the Woodland Library’. Found within Sherrardspark Woodland in Welwyn Garden City, this project is inspired by the literary principles of Umberto Eco’s Six Walks in the Fictional Woods. Framed as a parafiction, the project explores fertile ground to find meaning between principles of literary fiction and the architectural imagination. It is a venture into a realm of dichotomies between architecture and literature, architecture and landscape, architecture and the wilderness.

12.14–12.15 Arinjoy Sen, Y4 ‘Productive Insurgence: Towards the Autonomous (Re)production of Common(s) Within and Against the State’. This project seeks to question the ways in which the people of Kashmir, India produce and reproduce themselves in order to create an apparatus for (re)production towards a circular economy independent of State-Capitalist systems, facilitated by the continuous construction, maintenance and development of built infrastructure. The project situates itself within the ongoing political crisis and conflict in Kashmir to propose a productive network of commons within and against State control, towards a form of emancipation and sustenance for the community in this struggle.

12.16 Elliot Nash, Y4 ‘The Imitation Custom House’. This project proposes an architecture whose construction is rooted in the poetic. The Imitation Custom House is cast from the existing neo-classical Custom House, from which it derives its ‘copied’ physical character. The Thames is employed as both the building’s site and the medium of its construction; the concrete mix is cast with the rise and fall of the river’s tides.

12.17–12.18 Jean-Baptiste Gilles, Y4 ‘The School of Architectural Ignorance’. In the face of a climate emergency, this project rests upon the idea that sustainability can no longer be a step in the architectural process, but rather should become fundamental to its creation. In order to do so, a fundamental rethink of our relationship to the building, and our methods for creating buildings should happen. At the School of Architectural Ignorance, the curriculum turns academics specialising in climate research into teachers of students of architecture. Their ignorance of architecture is turned into an advantage, allowing for inventive and unprejudiced thinking, influenced by the constant mutations of the clay-constructed school as it reacts to its immediate environment.

12.19 Benjamin Sykes-Thompson, Y4 ‘Re-flooding the East Anglian Saltmarsh’. The government’s new Environmental Land Management System (ELMS) programme is used to fund four architectural insertions, dwarfed in size by the expanse they form, which breach existing sea walls and curate tidal flows. These insertions return drained land to sea and reframe societal notions of landscape ‘stewardship’ and the role of architecture in mediating this conversation.

12.20 Przemyslaw Rylko, Y5 ‘The British Library North’. This project investigates the relationship between ever-expanding knowledge and the physical experience of accessing it. Looking at the role of the library in the 21st century, the British Library North mixes the analogue and digital, the extraordinary and everyday, the monumental and intimate. Past and future exist together in a single building.

Elizabeth Dow, Jonathan Hill

Elizabeth Dow, Jonathan Hill

The architect will ‘always be dealing with historical problems –with the past and, a function of the past, with the future. So, the architect should be regarded as a kind of physical historian… the architect builds visible history’,1 wrote art historian Vincent Scully (1920-2017). The architect, therefore, is a ‘physical novelist’, as well as a ‘physical historian’. Histories and novels both need to be convincing but in different ways. The historian acknowledges that the past is not the same as the present, whilst the novelist inserts the reader in a time and a place that feels very present, even if they are not. Although no history is completely objective, to have validity it must appear truthful to the past. A novel may be believable but not true. As a history is a reinterpretation of the past that is meaningful to the present, each design is a new history. Equally, a design is equivalent to a fiction, convincing users to suspend disbelief. We expect a history or a novel to be written in words, but they can also be delineated in drawing, cast in concrete or seeded in soil.

A building can be designed for the present in acknowledgement of contemporary contexts, needs and desires. A design can also be a selective, critical and creative response to the past. Equally, a prospect of the future can be implicit in a design, which is always imagined before it is built and may take years to complete. Some architects design for the present, some imagine for a mythical past, whilst others create for a future time and place. In many eras, the most fruitful innovations have occurred when ideas and forms have migrated from one time and place to another by a translation process that is stimulating and inventive. Thus, a design can be understood as specific to a time and a place, and also a compound of other times and other places. In conceiving a design as a history and a fiction, we encourage a simultaneous and creative envisaging of the past, present and future in a single architecture.

We began the year by studying unrealised architectures to understand how politics, economics and aesthetics undermined their construction. We wanted to understand the stories – some fact and others fiction – that surround their histories, and to speculate upon the question: ‘How and why might this happen now?’ Our project was to design a public building that imagined the past, present and future in a single architecture, representing and stimulating the values and practices of two interdependent organisations – national and international – and multiple populaces – local, regional, national and international – that collaborate and prosper for mutual benefit.

Year 4

Amelia Black, Jonathon Howard, Laura Keay, Przemyslaw Rylko, Isaac Simpson, Aryan Tehrani

Year 5

George Entwistle, Tasnim Eshraqi Najafabadi, Niki-Marie Jansson, Francesca Savvides, Yu (Nicole) Teh, Yat Chi (Eugene) Tse, Dominic Walker, Yushi Zhang

Thank you to our Design Realisation tutor James Hampton and structural consultant James Nevin

Thank you to our critics: Ana Araujo, Alessandro Ayuso, Matthew Blunderfield, BarbaraAnn Campbell-Lange, Sam Coulton, Mark Dorrian, Adrian Forty, Murray Fraser, Stylianos Giamarelos, Niamh Grace, Penelope Haralambidou, Bill Hodgson, Mary Vaughan Johnson, Brian Kelly, Perry Kulper, Chee-Kit Lai, Constance Lau, Ifigeneia Liangi, Lesley McFadyen, Barbara Penner, Rahesh Ram, Sophie Read, David Shanks, Sayan Skandarajah, Tania Sengupta, Dan Wilkinson, Alex Zambelli

1. Vincent Scully, American Architecture and Urbanism, (London: Thames and Hudson, 1969), pp221, 257

12.1 Tasnim Eshraqi Najafabadi, Y5 ‘Transforming Coryton Refinery to a Post-Petroleum Garden Town’. This project is a critique of oil culture and envisages post-petroleum imaginaries for a former refinery in south Essex. An experimental garden town in a refinery, the proposal oscillates between poetic and practical, suggesting gardening as an agency and a way of life to provide for society and rehabilitate the dilapidated ecology. Composed according to available resources, it comprises infrastructural interventions and architectural typologies which blend the land’s past and future.

12.2 Niki-Marie Jansson, Y5 ‘The Ally Pally Annex: A masonry megastructure’. This project seeks to connect and dismantle established social and financial boundaries between London boroughs, in an attempt to address a group of urban, environmental, sociological and psychological problems. The design proposal manifests as a series of elevated and subterranean load-bearing masonry infrastructures that integrate themselves on a masterplan scale within London. They converege at a proposed megastructure undercroft at Alexandra Palace in north London. The infrastructure utilises the structural typology of the vault as a flexible building strategy.

12.3 Przemyslaw Rylko, Y4 ‘House of Leave and Remain’. This project reflects on the poor quality of discussion between so-called ‘Brexiteers’ and ‘Remainers’.

A sequence of acoustic, tactile and visual links attempts to connect people who might have different political opinions by establishing them as partners in conversation, instead of opponents to be defeated. The project is a response to the condition of Brexit, but is not ‘for’ or ‘against’ it; instead its primary aim is to foster principles of mutual understanding and respect.

12.4 Amelia Black, Y4 ‘The People’s Republic of Foundlings’. A critique of the Garden City Plan, ‘The People’s Republic of Foundlings’ is a micronation that uses the development of construction skills and community building to create a new egalitarian community typology. Each resident is fundamentally involved in both the material and immaterial construction of the community, utilising a systematic division of domestic and physical labour, as well as shared spaces, to alleviate pressures of a traditional ‘female’ caregiver role.

12.5–12.6 Jonathon Howard, Y4 ‘Sh*tHouse to Penthouse’. The project chronicles a selected sequence of domestic built interventions in unoccupied buildings in Hackney Wick that transfer from site to site and progressively accumulate into a complete building that recalls the memories of all the previous sites. The project narrates a renewal of current housing conditions through a variation of transformative processes that incorporate memories of the past and present, and that can be a suggestion for a potential future.

12.7–12.8 Laura A Keay, Y4 ‘Leyhalmode – The Fisheries Courthouse’. This project explores how a country might choose to rethink how it draws upon its own natural resources to build, govern and trade. It is set within a satirical Britain, in post-Brexit 2029, after a no-deal vote within parliament has led to to a halt in trade between the UK and EU. The architecture harks back to ‘older’ construction techniques, as the building industry is constrained by materials only produced and manufactured within the UK.

12.9 Isaac Simpson, Y4 ‘Terra Nullius: A vast land belonging to no-one’. The project’s ambition is to challenge the national borders of West Africa with another border, in order to redefine the term ‘border’; not as a line that splits cultures but as a line that connects. The West African institute of agroforestry will walk across the sub-Saharan lands planting rows of tree fields creating a reforestation border that re-fertilises the arid land for future agriculture. The locals decide the direction of these tree fields, in turn describing a new border mapped by the people, for the people.

12.10–12.12 Dominic Walker, Y5 ‘The Orkney Island Re-Forestry Commission’. This project seeks to understand the role of ‘origins’ and ‘endings’ in the production of architecture. The idea of ‘endings’ has become a growing theme in our comprehension of climate change, yet our minds are still captivated by the idea of salvation through technology. This project instead considers the idea that perhaps we have, as a species, reached a natural ending within the deep cycles of the world?

12.13 Francesca Savvides, Y5 ‘The Case for a New Architect’. The project is inspired by the recent movement to re-establish architecture departments in the public sector, and studies previous models of practice, such as the London County Council, to gauge what opportunities and capabilities would be afforded to architects in these new cross-boundary roles. The project proposes the ‘Bishopsgate School of Building’, a holistic school where architects, planners and construction workers would train together to develop a new age of ‘civicness’.

12.14 Yat Chi (Eugene) Tse, Y5 ‘A Museum of Hong Kong, by Hong Kong, for Hong Kong’. The Museum of Hong Kong sets out an approach for Hong Kong’s future in China. The result is a new reality of Hong Kong that contains China. The idea of reality in the architecture is expressed through symbolism. The project addresses the struggle of Hong Kong architects to retain a sense of their own cultural identity in modern international contexts by posing the questions: ‘What is Hong Kong?’, ‘What should be remembered?’ and ‘What should be forgotten?’

12.15–12.16 Yushi Zhang , Y5 ‘The National Agricultural College 2028’. The project proposes a new model for the future of farming and rural dwelling under a ‘no-deal’ Brexit scenario. Taking the form of an agricultural college, the project proposes the possibility of a more democratic, cooperative-owned farm, with a new ‘national agricultural conscription’. This is in order to regenerate a new attitude towards farming and making farming a life skill rather than a profession.

12.17–12.18 Yu (Nicole) Teh, Y5 ‘Institute for International Summit Negotiations’. As a reaction to the current de-globalisation movement, the project proposes an Institute for International Summit Negotiations, providing a space for press conference talks and private discussions. Sited in Singapore, a place seen as a neutral territory, it is a critique of the over-conditioned environment (both in terms of light and air) that itself seems to reveals a fear of darkness and disorder. The project focuses on the uses of darkness and natural ventilation, questioning how these ‘fears’ have brought about detrimental environmental consequences that should be addressed.

12.19–12.21 George Entwistle, Y5 ‘Wilding the City of London’. The project outlines a proposal for a town hall, set within a new forest planted in the heart of the City of London, replacing Guildhall as the seat of power. Covering ten acres of the Square Mile, the forest plays on historic precedent and folklore, and represents a place of liberty. The project is the antithesis of the current spatial conditions within the city and is divorced from its social, economic, and political hierarchies. Instead, it represents a more primal, natural order of governance.

Elizabeth Dow, Jonathan Hill

Year 4

George Entwistle, Niki-Marie Jansson, Francesca Savvides, Serhan Ahmet Tekbas, Yu (Nicole) Teh, Yat Chi (Eugene) Tse, Dominic Walker, Yushi Zhang

Year 5

Sophie Barks, Boon Yik Chung, Samuel Coulton, Iga Martynow, Daniel Meredith, Elin Soderberg, Eleni Zygogianni

Thank you to our Design Realisation tutor James Hampton and our DR structural consultant James Nevin

Thank you to our critics: Ana Araujo, Alessandro Ayuso, Roo Bernatek, Nicholas Boyarsky, Eva Branscome, Tom Coward, Edward Denison, Max Dewdney, Ben Ferns, Jan Kattein, Constance Lau, Ifi Liangi, Thandi Loewenson, Hugh McEwen, Tom Noonan, Samir Pandya, Rahesh Ram, Peg Rawes, Sophie Read, David Roberts, Tania Sengupta, Takero Shimazaki, Sayan Skandarajah, Eva Sopeoglou, Ro Spankie, Catrina Stewart, Michiko Sumi, Dan Wilkinson

Elizabeth Dow, Jonathan Hill

The Roman god Janus looked two ways simultaneously: to the past and to the future. The most creative architects have also looked to the past and to the future in order to reimagine the present. In many eras, the most fruitful architectural innovations have occurred when ideas and forms have migrated from one time and place to another, by a process of translation that has proved to be as stimulating and inventive as the initial conception. Twenty-first-century architects need to appreciate the shock of the old as well as the shock of the new.

According to Vincent Scully, the architect will ‘always be dealing with historical problems – with the past and, a function of the past, with the future. So the architect should be regarded as a kind of physical historian…the architect builds visible history’. The architect is a ‘physical novelist’ as well as a ‘physical historian’. As a history is a reinterpretation of the past that is meaningful to the present, each design is a new history. Equally, a design is equivalent to a fiction, convincing users to suspend disbelief. We expect a history or a novel to be written in words, but they can also be delineated in drawing, cast in concrete or seeded in soil.

As well as being tangible and physical, a city may exist in our memories and in our imaginations, and no-one shares the exact same knowledge or experience. Architects from the Renaissance to the present day have repeatedly emphasised the analogy of a house to a city, which is notably expressed in Andrea Palladio’s remark that ‘the city is nothing more or less than some great house and, contrariwise, the house is a small city’. The house he refers to is not the private house that we know today, but a house that combines private and public lives, whether a farm, a business or a workshop. Precedents for such a megastructure – that incorporates multiple functions in a single form – include Old London Bridge, Kowloon Walled City, and the welfare state universities of the 1960s. In response to climate change and the need to create a compact, sustainable and seasonal city, Unit 12 proposes that all the programmes – houses, schools, farms, cinemas, businesses, industries – necessary to sustain a rich and varied urban life should once again be integrated into a single complex –a city in a building in a city – an intimate megastructure.

Fig. 12.1 Elin Soderberg Y5, ‘The Woodland Parliament’. The Swedish Riksdagshus (eng: Parliament) is in need of renovation. The project proposes an alternative seat for the Riksdag, relocated from central Stockholm to the depths of the Royal National City Park forests at the fringes of the city, and speculates on a revived Swedish timber architecture that continues to draw upon the primitive memories of the forest.

Figs. 12.2 – 12.4 Eleni Zygogianni Y5, ‘The Village of the Two Rivers: A New Hope for the Future of Greece’. The project is a believable utopia, a modern myth and hypothesis on how Greece could be transformed in the future by repatriating the emigrated ‘Generation G’ that left the country after the economic crisis. The project reconstructs and revives the public ‘heart’ of the Cretan village in a surreal and symbolic

dialogue with the culture, history and stories of the island. Fig. 12.5 Sophie Barks Y5, ‘The Central Civil Registration Bureau’. The project reddresses the mandatory civil registration integral to the underpinning of our status within society and the key life events of birth, marriage and death. It considers the process as moments of civil celebration and reflection. Furthermore, the project examines architectural language and historical ‘styles’ with the hybridisation of the image of history within modern design.

Figs. 12.6 – 12.8 Iga Martynow Y5, ‘Slavic Free Theatre’. Inspired by the Belarus Free Theatre and designed with the aim of becoming its main performance space, this open-air theatre combines the aesthetics of Soviet Modernism with traditional North Slavonic architecture. Set within an artificially-created tidal meadow, the building explores notions of modern Slavic identity through symbolic ornament. Fig. 12.9 Boon Yik Chung Y5, ‘A Portrait of London’. A tragicomedy, this project explores the potential of architecture as a commentary on the human condition through designing spaces that reveal social tensions and existential angst, represented in paintings, embedded with political, social, cultural and art historical allusions, mirroring the grandeur and grotesque of contemporary urban living.

Fig. 12.10 Yu (Nicole) Teh Y4, ‘City of Darkness’. The City of Darkness is a critique of the over-conditioned environment of Singapore, from the excessive use of artificial lighting to air-conditioning. The proposal focuses on the design of the first building of the city, the house of the Mayor – a place of work and display for architecture and art of the dark.

Fig. 12.11 Francesca Savvides Y4, ‘The Green Line Parliament’. The project is sited in Cyprus in the Nicosia buffer zone and is a new parliamentary building to be used in the event of a solution to the ‘Cyprus problem’. Until that day the building stands as a monument and as a space for ongoing peace talks and communal projects. Fig. 12.12 Dominic Walker Y4, ‘The Monastic School of Architecture’. One might see architecture itself as a sort of quasi-religion, rich with tradition and myth.

Its practices have long been associated with ideas that stretch beyond economics and utility. This proposal seeks to celebrate such a mythic notion of architecture, through the implementation of a lifelong hermetic educational model.

Fig. 12.13 Niki-Marie Jansson Y4, ‘The Independent Province of Angel’. The Slow City responds to the erratic and fast paced nature of urban redevelopment prevalent in today’s society, and aims to exploit brick as London’s default material. The project manifests itself as an incremental infrastructural development within Angel, Islington, reintroducing brick manufacture as a local productive industry, in order to provide a catalyst for integrated social development.

Fig. 12.14 Yushi Zhang Y4, ‘An Art Academy for the Forgotten Coal Miners’. The project responds to the closure of the largest open pit coal mine in Fushun, China. It seeks to re-imagine the life within the coal mine after its industrial life span. The project explores the process in finding a new architectural language and identity for the abandoned site and its forgotten people. Fig. 12.15 Serhan Ahmet Tekbas Y4, ‘The Monument To The Lovers of Famagusta’. Sited within the contested grounds of Famagusta in Northern Cyprus, the monument and performative architectural characters are constructed of social, cultural and political stories that propose a future for the ghostly Salamis Ruins. The project investigates the role of the storyteller architect and explores dichotomies that include written/oral stories, human/machine and human/architecture.

Fig. 12.16 Yat Chi (Eugene) Tse Y4, ‘The Guild of Bitcoin Miners’. The project outlines the disarray and ugliness of the capitalist society in the UK by using the rise of Bitcoin to pose the question ‘what is the most valuable?’. The Guild would develop a new Gothic language for the 21st century and offer a school to re-educate unemployed Welsh coal miners with a new craft. Fig. 12.17 George Entwistle Y4, ‘Transactions of the Ancient Monuments Society’. The project takes the form of a design for the headquarters of a new and alternative planning authority for London. A subverted spatial sequence and curious detailing in the design of the headquarters aims to assist in tackling the corruption that is currently present within the planning process.

Fig. 12.18 Daniel Meredith Y5, ‘HMYOI Hutton’. The project is a young offenders institution, sited near Torridon in the Western Highlands of Scotland. The institution is located directly over the Lewisian Complex, the oldest bedrock geology in the UK. Through building with such ancient materials, excavated from the site, the institution aims to instil an appreciation of the present. Fig. 12.19 Samuel Coulton Y5, ‘London Resomation and Physic Garden’. Inspired by Derek Jarman, and Yves Klein’s blue monochromes, the project is a proposal to introduce a resomation necropolis and physic garden; in which our relationship with death is readdressed through the implementation of a botanical garden on the site, fed by the nutrient rich effluent water, generated through resomation.

Matthew Butcher, Jonathan Hill

Year 4

Sophie Barks, Boon Yik Chung, Samuel Coulton, Iga Martynow, Dan Meredith, Elin Soderberg

Year 5

Christia Angelidou, Mariya Badeva, Emma De Haan, Mihail Dinu, Clare Hawes, Rawan Hussin, Raphae Memon, Meya Tazi, Ioana Vierita

Thank you to our Design Realisation tutor James Hampton of Periscope, and DR structural consultant James Nevin of Blue Engineering

Thank you to Ben Clement and Sebastian de la Cour of benandsebastian

Thank you to our critics: Ana Araujo, Alessandro Ayuso, Shumi Bose, Eva Branscome, Barbara-Ann Campbell-Lange, Tom Coward, Oliver Domeisen, Ben Ferns, Paul Fineberg, Omar Ghazal, Sean Griffiths, Jessica In, Chee-Kit Lai, Constance Lau, Lesley McFadyen, Tom Noonan, Luke Pearson, Peg Rawes, Gilles Retsin, Tania Sengupta, Ana Vale, Nina Vollenbröker, Dan Wilkinson

Matthew Butcher, Jonathan Hill

The desire for the new is seen in our need to consume the latest fashions, technologies, artworks and ideas. The promise of the new stimulates the recurring cycles of production and obsolescence that feed consumption in a capitalist society. But it is also a creative and critical stimulus to cultural, social and technological innovation. This year, our aim is to explore how this informs the ways we conceive and produce architecture.

Often, what is presented as new is not new at all, but a revival of an earlier form, idea or practice. To ask ‘What is new?’ involves other questions: why is it new, how is it new, and where is it new? Alongside cultural and social investigations into notions of newness, we ask what is really new in any subject that concerns us.

The 20th century avant-garde were the quintessential advocates of the new. They sought to discover art forms that would question bourgeois traditions and transform society culturally, socially and politically. Their influence was profound even though they were assimilated into the cultural establishment. To explore the possibilities for a better world, we ask what is a new avant-garde today, what should it propose, what values and systems should it question and why.

To understand what is new, we investigate the present, the past and the future: we think historically. Defining something as new is an inherently historical act because it requires an awareness of what is old. We are not interested in unquestioning newness for its own sake, and we do not wish to reject the past or negate its value. Sometimes the old is even more radical than the new. Rather than the modernist tabula rasa in which the new destroys the old, we propose an evolving dialogue between the new and the old in which one informs the other.

Thomas More’s Utopia celebrated its 500-year anniversary in 2016, reviving questions of its present relevance. One possible translation of its full title ‘De optimo rei publicae deque nova insula Utopia’ is ‘Of a republic's best state and of the new island Utopia’. More was reputed to have refused to translate his Utopia from Latin, but we look at translation as a means to imagine the new.

Our site is Berlin. More than any other European city, Berlin offers a cavalcade of buildings that were once really new. Continually reinventing itself, Berlin offers a historically and politically fecund environment in which our students proposed a state, an island or a quarter of considered newness. Initially this new state was remotely imagined from London. In Berlin we set its foundations, and on our return to London this ‘city within a city’ was brought to fruition.

Fig. 12.1 Raphae Memon Y5, ‘Tierwald: Berlin’s City-ArchitectScenographer’. The project is a landscape of buildings-aspublic-squares, deep in a constructed forest within Berlin’s Tiergarten. In the centre is the city-architect-scenographer, a yearly appointed artistic director of the city who coordinates the fragmented architectures so that they transform during the interstices between sunrise and sunset. The design facilitates scenographic proposals for the city, which are designed, built, tested, performed and stored. Light creates perceptive conditions of darkness and provokes scenographic occupations for the future. Fig 12.2 Iga Martynow Y4, ‘Museum for Dada Art’. The museum is located on the exact site of a 1920s exhibition. It plays on ideas of the nonsensical and absurd, recreating the original gallery as a labyrinth of

interconnected rooms, inhabiting the spaces between the white, superfluous grid. Fig. 12.3 Elin Soderberg Y4, ‘The New Friedrichshain Bank’. Addressing themes of financial speculation and time, the project positions itself within the recurring property cycle. Set within a geological and seasonal timescale, it discusses the possibility of a new model for slow banking. Fig. 12.4 Boon Yik Chung Y4, ‘Museum for 20th Century Arts’. A fix for Herzog & de Meuron’s botched attempt, the project employs creative strategies associated with artistic practice in the synthesis of idea and physical production of architecture, to create gallery spaces truly representative of 20th century arts: radical, humorous and subversive. The alternative proposal tests the limit of architecture as a creative practice, and personal and societal