Design Anthology PG17

Architecture MArch (ARB/RIBA Part 2)

Compiled from Bartlett Summer Show Books

Architecture MArch (ARB/RIBA Part 2)

Compiled from Bartlett Summer Show Books

At The Bartlett School of Architecture, we have been publishing annual exhibition catalogues for each of our design-based programmes for more than a decade. These catalogues, amounting to thousands of pages, illustrate the best of our students’ extraordinary work. Our Design Anthology series brings together the annual catalogue pages for each of our renowned units, clusters, and labs, to give an overview of how their practice and research has evolved.

Throughout this time some teaching partnerships have remained constant, others have changed. Students have also progressed from one programme to another. Nevertheless, the way in which design is taught and explored at The Bartlett School of Architecture is in our DNA. Now with almost 50 units, clusters and labs in the school across our programmes, the Design Anthology series shows how we define, progress and reinvent our agendas and themes from year to year.

2024 For Things to Remain the Same, Everything Must Change

Yeoryia Manolopoulou, Nasios Varnavas, Tamsin Hanke

2023 The Dialogical Architect

Yeoryia Manolopoulou, Thomas Parker

2022 Between

Yeoryia Manolopoulou, Thomas Parker

2021 Extended Mind

Yeoryia Manolopoulou, Thomas Parker

2020 Prompt Score Ensemble

Yeoryia Manolopoulou, Thomas Parker

2019 Deep Future, Deep Past

Yeoryia Manolopoulou, Níall McLaughlin

2018 The Protagonist

Yeoryia Manolopoulou, Níall McLaughlin

2017 2 3 5 7 11 13 17

Yeoryia Manolopoulou, Níall McLaughlin, Michiko Sumi

2016 Taking Time

Níall McLaughlin, Michiko Sumi

2015 Devo Max

Yeoryia Manolopoulou, Níall McLaughlin, Michiko Sumi

2014 The Open Work

Yeoryia Manolopoulou, Níall McLaughlin, Michiko Sumi

2013 Materials: Ideas

Yeoryia Manolopoulou, Níall McLaughlin, Michiko Sumi

2012 Take It from the Top

Yeoryia Manolopoulou, Níall McLaughlin, Michiko Sumi

2011 Do Undo Do

Yeoryia Manolopoulou, Níall McLaughlin

2010 Decay and Emergence – The Becoming of Cities

Adam Cole, Tilo Guenther, Níall McLaughlin

2009 The Recovery of the Real

Yeoryia Manolopoulou, Níall McLaughlin

2008 The Absence of the Architectural Object

Yeoryia Manolopoulou, Níall McLaughlin

2007 Migrations

Yeoryia Manolopoulou, Níall McLaughlin, Bev Dockray

2006 Unreal Constructions

Yeoryia Manolopoulou, Níall McLaughlin

2005 Emerging and Dissolving Places

Yeoryia Manolopoulou, Níall McLaughlin

2004 Ground-Horizon

Yeoryia Manolopoulou, Níall McLaughlin

Yeoryia Manolopoulou, Nasios Varnavas, Tamsin Hanke

While buildings are rooted in place, they are planetary creations, embedded in a global tangle of relations. Architecture can no longer be conceived as purely site-specific. It intertwines with the local, yet it must evoke a planetary imagination and set planetary boundaries to care for the Earth as our client. Ultimately, buildings need to be gentle with the places they belong to and the Earth system as a whole.

The Earth’s crust is the thickest physical palimpsest of time, accumulating fossils, minerals and natural resources while also tracing an overpowering Anthropocene. Most importantly, this ‘underland’ stores the sediments of human creations, our memories and hopes, and the secrets and failures of our ancestors. As architects, we are in the midst of making ‘the palaeontology of our present’. 2

This year we considered how our creations weigh and form strata for the future. We questioned the relationships between contemporary life and the passage of a longer time, entombed beneath our feet and released by building processes. We imagined buildings as vessels for living and, at the same time, thought of them and the tools of their making as fossils-to-be.

Our field trip to Sicily raised opportunities for an architecture that engages with contemporary forms of cohabitation, history, myth, migration and settlement, resources, the climate and a magnificent natural world. We created projects that are based on a deeper understanding of doing and undoing architecture, the rise and fall of cities and infrastructures, village depopulation and development, temporality, ecology and adaptation, plant and animal habitats.

For PG17 the architect mediates and works dialogically in an emergent culture. Dialogical architects develop processes of design rather than single products. They weave together a creative web of connections so that architecture can benefit from chance encounters, negotiations, and the shared proximity between materials, ideas, social realities and desires.

Year 4

Panagiota Grivea, Peter Holmes, Sarah Kay, Richard Kirk, Ying Tung (Ruby) Ng, Eleanor Pavier, Amy Peacock, Georgie Stephenson, Zekun Tong, Giacomo Francesco Vinti

Year 5

Basil Babichev, Rory Browne, Tessa Lewes, Jeff Qu Liu, Kevin Poon, Thibault Seiji Ryba Quinn, Ben Smallwood

Technical tutors and consultants: James Daykin, Sophia McCracken, Ioannis Rizos, Michael Woodrow

Thesis supervisors: Hector Altamirano, Kelly Alvarez Doran, Jane Hall, Joshua Mardell, Oliver Wilton, Stamatis Zografos

Critics: Jessam Al-Jawad, Felicity Atekpe, Kirsty Badenoch, Colin Herperger, Madhav Kidao, Guan Lee, Francesco Moncada, Will McLean, Thomas Parker, Lorenzo Perri, Sophia Psarra, Mafalda Rangel, Edoardo Tibuzzi, Mike Tonkin, Victoria Watson, Mika Zacharias

Partners: Drawing Matter, Lucia Pierro

1. This title is from Giuseppe Tomasi di Lampedusa, The Leopard (London: Vintage, 1958).

2. Robert Macfarlane, Underland: A Deep Time Journey (London: Hamish Hamilton, 2019).

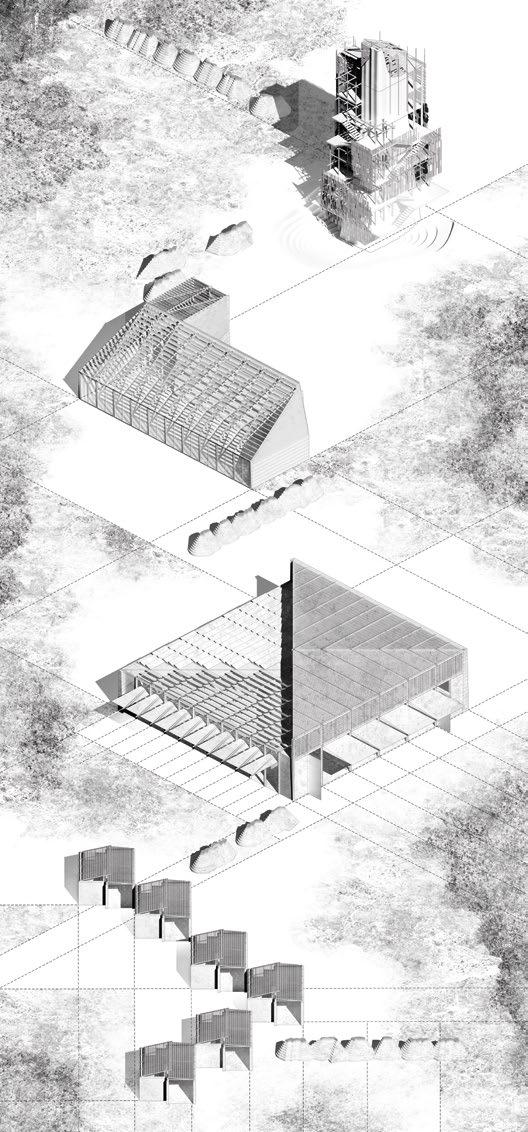

17.1 Jeff Qu Liu, Y5 ‘Engraved Cycles’. Inspired by Sicily’s interdependent scales and geology, the project weaves the life cycles of a marine, human and regenerative lithosphere using local limestone and granite. Located in Addaura, the proposed design features a marina complex and a civil registry, revitalising the old port’s industrial remains. The proposal integrates Sicilian human and material timescales into a sustainable architectural possibility.

17.2 Thibault Seiji Ryba Quinn, Y5 ‘Fragmenting and Condensing Civic Space’. This project reinterprets civic space in the context of dynamic sociopolitical and geological forces shaping Palermo. The revealing of hidden underground waterways and railway tracks overlaps with the connection between institutional power and local people. The fragments of the jigsaw of diverse public spaces are condensed as a common ground for the multicultural people of Palermo.

17.3 Zekun Tong, Y4 ‘Water Field Islands’. An open kindergarten is proposed within a public landscape on a reclaimed coastal habitat in Palermo. The landscape negotiates digital scripting and physical modelling in the abstraction of water. The buildings provide various children’s learning spaces for the nearby marginalised community. A playful, light and airy environment is created through the use of wooden trusses and waterreed cladding, locally sourced.

17.4 Peter Holmes, Y4 ‘All That’s Left Behind’. Many buildings in Prizzi stand abandoned due to depopulation. Should we preserve the hill town as an edifice, or extract its stone to build anew? Prizzi is carved up, exploited for its material resources and renewed to meet the challenges of its reduced population. What is justified when all gains are tied to a material loss?

17.5 Eleanor Pavier, Y4 ‘Welfare Island Hostel’. This project explores the retrofit and reclamation of Giarre’s 1985 abandoned Olympic Polo and Athletics Stadium. Addressing unprecedented environmental and agricultural challenges, this hostel sits on a key migratory path for tourists, refugees and job seekers, and uses the stadium’s foundations to emerge as a testbed for radical agrotourism and revolutionary education.

17.6 Ying Tung (Ruby) Ng, Y4 ‘Casting, Imprinting and Constructing’. The project explores material contingencies through the construction of physical models. The collection of models demonstrates the experimentation process of a new casting method that uses an elastic membrane to enhance material performance and capture the expression of materials as they transition from a liquid to a solid state.

17.7 Ben Smallwood, Y5 ‘The Notifier of the Anthropocene’. The project is located in Sicily, specifically at the island’s largest landfill. The building serves as an archive that interacts with the worsening conditions of flooding, material extraction and waste. The structure adopts the haphazard Sicilian tiled roofs to house proxy records and apparatus that naturally scar, stain and erode the building, recording the worsening climate.

17.8 Tessa Lewes, Y5 ‘Hades and Persephone’. This project is a spatial manifestation of the Sicilian myth of Hades and Persephone. The architecture is an extension of the landscape, offering a poetic spatial journey through a landscape of divine ritual. A farm adapted to a future climate sits above an excavated myth-telling theatre. The project preserves the divine, dramatic and eternal narratives of Sicily’s mythical past.

17.9 Sarah Kay, Y4 ‘Incompiuto’. This project engages with an incomplete building, ‘the palace of concrete’, in the unfinished town of Librino. It explores material reuse through processes of carving and demolition, allowing light, air and space for gathering. The building builds and unbuilds itself, mirroring the cycles of construction and demolition seen in many of Sicily’s cities today.

17.10 Richard Kirk, Y4 ‘The Hill of Shame’. In Pizzo Sella, a mountainside is scarred by illegal mafia construction. Imagined in phases, temporary architectural installations of a living herbarium provide infrastructure for both the demolition of politicised ruins and a simultaneous cultivation of restorative gardens. Grounded in a culture of site-specific reuse, material reclamation defines the architecture, allowing the materials by which the mountain was defaced to enact its restitution.

17.11–17.12 Rory Browne, Y5 ‘Towards Slow Heritage’. The project proposes minimal landscape infrastructure within the Necropolis of Pantalica’s UNESCO buffer zone. A typology of platforms and plinths enhances visits to the site while small-scale archaeological, film and music festivals activate it seasonally. The phased proposal nurtures a slower connection to the land, offering a temporal recognition of the site and the dynamic rhythms that drive it.

17.13 Georgie Stephenson, Y4 ‘Born From Ashes’. Influenced by recent effects of deforestation, Sicily‘s dramatic climate has led to numerous wildfires spreading across the region. At the heart of Monte Pellegrino, the project bridges the often blurred boundaries between architecture, landscape and fire. Reflecting the revival of the fire-damaged forest, the project illuminates the potential timber architecture can have in wildfire-prone areas, reimagining the fire to protect and preserve.

17.14 Basil Babichev, Y5 ‘The Proportional Path: Sowing Seeds of Coexistence’. In Sicily, the borghi are villages built in the early 20th century to politically indoctrinate rural populations. Today, many remain in ruins due to decolonisation, tourism and rural marginalisation. This project addresses attempts at reviving these villages as tourist centres by occupying an incomplete viaduct and using salvaged borgo materials that are consolidated to liberate areas of land.

17.15 Panagiota Grivea, Y4 ‘Life in Common: Past and Future Realities of a Ruin’. This project approaches Western Sicily’s fragmented context through the life of Poggioreale, an abandoned town. The proposed re-inhabitation uses urban collaboration, cooperative structures and reconstruction as strategies for communal living in a cooperative housing scheme. The project recognises the cyclical nature of human migration by using movie-making to communicate the town’s past and present realities, as well as alternative futures.

17.16 Giacomo Francesco Vinti, Y4 ‘La Pescheria’. The project entails the design of a fish-storing unit in Palermo’s traditional market. A 1:5 sectional model of La Pescheria’s fish-storing unit demonstrates the key mechanisms and systems involved in fish preservation. At this scale, the elements showcase the true materiality and construction processes involved in a 1:1 structure. The model featured has thus been used to illustrate functionality in real life.

17.17 Amy Peacock, Y4 ‘Palermo Citizen’s Advice Bureau’. This project investigates the potential of knitting as an architectural response to the urban neglect of the Albergheria neighbourhood of Palermo. Using the skeleton of an existing building, knitted structures and enclosures form a centre to help local inhabitants in navigating the legal and bureaucratic systems of Palermo.

17.18 Kevin Poon, Y5 ‘Beyond Surface’. The project investigates the reuse of discarded marble, utilising marble ‘waste’ as a primary building material, and embracing the raw and unrefined qualities of stone. Inspired by photographic work of marble quarries, the design uses remnants and ongoing construction processes to add layers to the architecture. It is presented as timeless groundwork that resembles geological formations.

Yeoryia Manolopoulou, Thomas Parker

This year PG17 explored Mikhail Bakhtin’s concept of dialogism and the potential of his philosophy of language and ethics in architecture. Dialogism is determined by the capacity of an author to integrate other positions of self and unresolvable dialogues in their work. Many of our limitations in making a caring, enjoyable and sustainable world, both as architects and as citizens, can be overcome by developing and using creative processes that are truly dialogic.

Architects engage with a vast spectrum of environments and are asked to accommodate an unending array of different desires and needs. Responding to this complex reality, we have become sceptical of monologues and the monologic design narratives that dominate our discipline and profession; instead, we aim to practice as dialogical architects. The dialogical architect fosters an empathic self who attends to manifold perspectives, cultures and histories, even when these are contradictory, and who embodies multiple positions and counter-positions within a single project.

We have sited our projects in Porto and the Douro Valley, responding to a range of individual interests: prehistory and the fossil fuel age; river and coast ecologies; stone assemblages; architectural ceramics; purification in housing; migrating communities; scripting histories; sound in architecture; unfinished building; mental health and the representation of multiple realities; mobile structures; and the life cycles of materials. Each project is research-based and constructs an architectural thesis that is explicitly manifested in the design proposition. The proposed buildings are contextual and interplay with the social and political facets of place. Iteration, experimentation and improvisation are balanced by traditions and continuities.

In addition, this year we developed a one-day drawing project together with students and staff from the Porto School of Architecture, also known as FAUP. Our shared work, called ‘Drawing in Dialogue’, explored how the buildings and landscapes of FAUP, designed by Álvaro Siza, have been populated by multiple intentions and experiences during the last 40 years. We responded to FAUP’s stories – told by the gardener, the carpenter, the engineer, the historian, the architect, the teacher and the student – with numerous hand drawings, the making of a collaborative intersectional topography and a machine learning drawing process.

Year 4

Patricia Bob, Jeff Qu Liu, Heba Mohsen, Nicholas Phillips, Kevin Kai Yin Poon, Thibault Quinn

Year 5

Daeyong Bae, Ceren Erten, Matthew King, Desire Lubwama, Karin Kei Nagano, Vilius Petraitis, Malgorzata Rutkowska, Anton Schwingen, Tia-Angelie Vijh

Technical tutors and consultants: James Daykin, Sophie McCracken, Ioannis Rizos, Jose Torero Cullen

Thesis supervisors: Hector Altamirano, Matthew Barnett Howland, Brent Carnell, Jane Hall, Guang Yu Ren, Tim Waterman, Oliver Wilton, Fiona Zisch

Critics: Jessam Al-Jawad, Nat Chard, Malina Dabrowska, Mary Duggan, Fernando Da Silva Ferreira, Anne Marie Galmstrup, Jonathan Hill, Clara Kraft Isono, Nikoletta Karastathi, Chee-Kit Lai, Alex Pillen, Sophia Psarra, Jonathan Tyrrell, Tim Waterman, Victoria Watson, Izabela Wieczorek

Workshop collaborators: Noémia Herdade Gomes with FAUP staff and students

Additional workshop support: Jose Pedro Sousa, Tim Waterman

Field trip collaborator: Fernando Da Silva Ferreira

Invited speakers: Joanne Chen, Ben Hayes

17.1 Group Work, Y5 ‘Dialogic Cube’. Sixty-four cubes carved to represent stories around Vila Nova de Foz Côa, where the palaeolithic open-air rock art is located.

17.2–17.3 Anton Schwingen, Y5 ‘Stone Operations’. The project investigates stone as a building material and as a vessel of collective memory. Porto is built from stone and rests on a solid granite massif. A new living quarter is constructed by quarrying space into the rock and rebalancing stone on the site. Stone forms an inhabitable geological stratum, serving as the foundation for multi-sited constructions in an ongoing assemblage. It combines inert local geology with nomadic light structures.

17.4 Vilius Petraitis, Y5 ‘Public Works: Performing the Backstage’. The project transforms construction and reconstruction processes into spatial experiences. It features three key elements – the backstage, reuse looms and a cork mason yard – existing at different timescales. The project reimagines the architect as a playwright, crafting dynamic performances of design that respond to the evolving needs of Porto. Through the project, we experience the city as a living, breathing assemblage undergoing perpetual change.

17.5 Matthew King , Y5 ‘Resonating Deep’. The Port of Leixões is expanding and its interests are diverging from those of adjacent communities and ecologies. How can architecture look to dismantle the monologic nature of the port, generating a dialogue between marine life, people and coastal infrastructure? This project looks at the convergence of coastal voices, stitching them together through a language of monolithic spaces and fractal surfaces. Beneath the tide, benthic life is encrusting and sediment is accumulating – processes that the architecture makes visible and explorable. 17.6–17.7 Tia-Angelie Vijh, Y5 ‘You Don’t Live to Work, You Work to Live’. The project intends to create a new and improved way of living for the people of Porto. It explores healthy living conditions through Portuguese textile heritage in conjunction with the current housing crisis. The project takes place in Porto along the banks of the Douro River, focusing on implementing a new housing scheme of white, biomorphic architecture designed as an extension of Porto’s industrial worker housing typology. 17.8, 17.10–17.11 Daeyong Bae, Y5 ‘Traces: Realisation of Deep Time’. The project explores traces in artefacts and architecture as a dialogue between the past, present and future. Inspired by palaeolithic engravings, it focuses on the Matosinhos oil refinery’s regeneration in Porto. During a four-year decontamination phase, the proposed architecture utilises cleaned soil for temporary buildings. These architectures symbolise the end of the fossil fuel era and mark the site’s history. Over time, the fragments of these buildings will remain, reminding us of the site’s past and the transition away from fossil fuels.

17.9 Jeff Qu Liu, Y4 ‘The Bonfim Detachment’. The project builds upon Claude Parent’s theory of the ‘oblique’ to create a dynamically unstable building. It incorporates an oblique economy of materials, promoting decay on the building components’ lifecycles, while perished materials are recycled into new components. The project, situated in the old industrial district of Porto, addresses housing shortages and conflict between locals and tourists through urbanism-centred workshops and repurposing what remains into a new living reality. 17.12–17.14 Ceren Erten, Y5 ‘Self/Other’. The project proposes a wellbeing facility run by a mental health charity in Porto. Catering to people in different zones of the cognitive spectrum, the scheme questions the perceived superiority of the shared reality of everyday life. Exploring societal tensions of experiencing otherness, the project creates a space for interaction between the perceived self and the other. It promotes openness and

acceptance, instead of avoidance and neglect in the context of mental health.

17.15 Kevin Kai Yin Poon, Y4 ‘The River Foundation’. The project challenges the existing large-scale river infrastructure, highlighting the irreversible damage caused by human intervention. Located in Foz Côa, Portugal, the proposal restores the scarred landscape and supports water-quality research. Utilising local materials and traditional techniques, the architecture sits in harmony with its surroundings. The site harnesses energy from the river through a decentralised, microrenewable approach. The project preserves the site’s significance, empowers the community and raises awareness around climate change and water management.

17.16, 17.19 Desire Lubwama, Y5 ‘Fabrica, Porto’. Fabrica takes the methodologies of both architecture and textile design in parallel to create a space with its own specific programme, fitted to its urban context. The project uses the graphical language of garment patterns, symbols and processes from both North African and Portuguese textiles, with space being transformed into structural garments. The dialogue between design control and losing control is explored through tailoring and surface dressing, which play as communicative capacities that inform the identity of the body.

17.17–17.18 Karin Kei Nagano, Y5 ‘Landscape of Excessive Labour’. The autonomous housing intervention in Campanhã celebrates non-standardised building tradition, emphasising expression, improvisation and agency. Situated in an abandoned industrial site, it reclaims embedded labour history. Addressing the global housing shortage, it provides a sustainable, affordable housing scheme for residents, challenging the rigid rhythms of working-class homes under the Estado Novo regime. Through the introduction of flexible fabric formwork and casting, it revolutionises construction methods.

17.20 Heba Mohsen, Y4 ‘Sit Tibi Terra Levis’. The project proposes a settlement and open-air museum on a rural Portuguese hillside. Using schema as a tool and representation as a strategy, architectural forms created from forgotten histories are recontextualised, distorting linearity and carrying characteristics from the original source to a new time. Ideas of singular authorship and the ‘definite’ hand of the architect are questioned as we examine what might happen to architectural practice if we allow self-organising worlds to bloom.

17.21–17.22 Thibault Quinn, Y4 ‘Mind the Gap’. This project proposes the reinstatement of Porto’s abandoned customs railway as a moving market, transporting goods and people in mobile carts which inhabit a framework perched on the Douro cliffside. Transcultural trade is reintroduced to an area where it has been forced out, with a system that also brings the market to new neighbourhoods along the line. An artery of import and export is reimagined with a migratory and reconfigurable architecture that adapts to the city’s social and geological flows.

17.23–17.24 Malgorzata Rutkowska, Y5 ‘The Part and the Whole: Layering Climate Conditions’. The project investigates the preconception of controlling thermal comfort through ceramic material innovations. It proposes a work/live community in a post-industrial site hidden in a backyard behind a bourgeois townhouse in the district of Bonfim, Porto. The city’s forgotten ceramic manufacturing past intertwines with communal living. The residents and visitors can explore spaces –private and public, indoor and outdoor – that create layers of intermediate climatic characteristics.

Yeoryia Manolopoulou, Thomas Parker

Architecture connects. It makes myriad interconnections between physical matter, systems of knowledge, cultures and experiences – entities that are never fixed but in constant dialogue. Architecture also separates. Yet neat oppositions no longer exist, so our concept of ‘between’ aims to challenge common dichotomies maintained in our discipline: nature and things, local and global, the individual and the collective, the settler and the nomad. To produce a sustainable, fairer and more inclusive architecture, we need to rethink such distinctions.

‘Between’ suggests a spatial and temporal transition, as well as liminality. What happens at thresholds, on borders, in the interval between before and after? An in-between situation can cause friction and discontinuity, but can also be the source of enormous creative potential for new kinds of architecture and new kinds of connection.

We are interested in intermediate structures, hybrid objects and processes. We understand buildings as environments that entangle human conditions, as well as components and services that are themselves in flux. Buildings are physical continuities of matter changing at different rates. What exists beneath them is multifaceted, so our foundations are both literally and metaphorically compromised. Lands, oceans and communities are in transformation. Migration, social health and environmental ethics concern us urgently.

Our projects are always works of adaptation. Learning to design with the material and conceptual remains of situations will prepare us for working sensitively with residues of conditions in the future.

We started the year by living and making at Grymsdyke Farm. This collaborative work required scaffolding the size of our team configurations from two to four and ultimately to 16 students. We drew on and collectively glazed more than 360 ceramic tiles. Together we built a large-scale landscape installation involving found materials on the site and the spatial unravelling of three kilometres of rope. Drawing upon this initial performative work, we then developed individual design proposals on sites of our choice in Milton Keynes. In addition, all fourth year students assembled the Milton Keynes Collective, a collaborative manifesto with pilot design projects, expertise and ideas for the future of a sustainable and dynamic city.

Year 4

Ceren Erten, Matthew King, Desire Lubwama, Karin (Kei) Nagano, Vilius Petraitis, Anton Schwingen, Tia-Angelie Vijh

Year 5

Zhongliang Huang, Rebecca Lim, Polina Morova, Kaye Song, Negar Taatizadeh, Ella Thorns, Alexander Venditti, Janet Vutcheva, Qingyuan (Rubin) Zhou

Technical tutors and consultants: James Daykin, Lidia Guerra, Guan Lee, Jessie Lee, Rachel Pattison

Critics: Barbara-Ann Campbell-Lange, Nat Chard, Hannah Corlett, Murray Fraser, Kostas Grigoriadis, Perry Kulper, Chee-Kit Lai, Constance Lau, Guan Lee, Anna Liu, Petra Marko, Emma-Kate Matthews, Michiko Sumi, Jonathan Tyrrell, Oliver Wilton, Simon Withers

17.1 Group Project, Y4&5 ‘Sixteen’. Collaborative installation and performance carried out in the first term with materials found at Grymsdyke Farm, Buckinghamshire.

17.2 Group Work, Y4&5 ‘An Archaeology of Making’. This assemblage gathers some of the physical work produced by PG17 during this academic year, highlighting a studio ethos that is based on coexistence and the supportive experience of making and doing.

17.3 Ceren Erten, Y4 ‘Waste + Value’. The project proposes a new residential expansion strategy for Milton Keynes using a recycled plastic-block construction system. Critiquing the current cultural misuse of plastic –an extremely long-lasting material – as throwaway, the project explores tensions between disposability and permanence.

17.4 Qingyuan (Rubin) Zhou, Y5 ‘Land Graffiti’. Located at a Roman archaeological site at Stantonbury, a small village in Milton Keynes, the project challenges the public to understand the past as having multiple narratives by designing methods of excavation and reinterpretation. This proposal responds to the authorised heritage discourse that cements the area’s rich archaeological significance and invites the local community to manifest and craft the multiplicity of their history.

17.5 Karin Kei Nagano, Y4 ‘Finding Counterpoint’.

This project offers a counternarrative to the initial 1960s plan of Milton Keynes which, by muffling urban noise, resulted in the absence of interaction between its different communities. Reclaiming rare remaining pockets of public space, the project brings sound to the forefront and envisions its function as an instrument, giving the community a voice and enabling it to evolve.

17.6 Negar Taatizadeh, Y5 ‘Housing Reciprocity’.

The project anchors itself in three thematic subjects: rebuilding, reconnecting and revealing. It proposes a systematic approach towards rebuilding to reconnect the community across generations while revealing the clay material context of this location. The project is fascinated with the liminality of materials and celebrates their impermanence. A transitory architecture is formed, one that promotes connection, reciprocity and care above all.

17.7 Kaye Song, Y5 ‘Double Edged’. A design for a porous and accessible edge to Milton Keynes emphasises its position as a thoroughfare city. A proposal for a green, populated and community-owned distribution park bridges the utilitarian and industrial with the wild and organic, welcoming hybridity and fluidity as essential to the contemporary experience of the English landscape.

17.8 Anton Schwingen, Y4 ‘Theatre of Matters’.

The construction industry is responsible for a large proportion of global CO2 emissions, necessitating a radical change in the way we build. The theatre is a storage and inventory facilitating the shift to reusing building components. It also becomes a space to debate, observe juxtaposition and negotiate the city of the past and the future.

17.9 Zhongliang Huang, Y5 ‘Wayward Growth’. This proposal reinvigorates the industrial ruins of the Wolverton railway works by adapting and reusing the derelict building material while growing a new communal garden. The proposal also contains a workshop and accommodation units for lifelong learning in the arts and sciences.

17.10 Vilius Petraitis , Y4 ‘Between Estate’. The project establishes a shared playing field, which lays the groundwork for a temporary cohousing scheme, weaving communities together while their homes undergo vital repairs. With doubt and delight as design parameters, the project looks at creating an architecture where the building is not an end in itself. Instead, the constructions encourage the continual need for change.

17.11 Matthew King, Polina Morova, Anton Schwingen, Ella Thorns, Y4&5 ‘Quartet’. A device that connects four people by joining couples through an interdependent junction.

17.12 Alexander Venditti, Y5 ‘A Point in Time’. The Point cinema multiplex has been slated for demolition. Rejecting a tabula rasa restart, an alternative future inspired by its cinematic history is proposed, which sees the iconic site transformed into an open-air film stage. The oscillating states of set demolition and reconstruction strip back the veil of cinema and reveal the secrets behind its production, all while filling a gap of cultural identity within the city.

17.13–17.14 Polina Morova, Y5 ‘Softening Milton Keynes’. The centre of Milton Keynes offers an experiential example of rigid living where urban components of the city feel solitary and separate, and where life becomes a series of discrete experiences, clear-cut roles and identities. Within this context, the proposed park becomes a respite from daily life, offering a change of scene where the alienation one feels in the city becomes the poetic alienation one feels in nature.

17.15 Ella Thorns , Y5 ‘Consequential Cognition’. This project designs and interrogates a new foodbased masterplan for the neighbourhood of Oldbrook, Milton Keynes. Criticising the dissonance of our current food system, the architecture processes food and consumption by-products around its users, resulting in consequential awareness.

17.16 Janet Vutcheva, Y5 ‘Quarrying Fluidity’. The project investigates river valley quarrying and proposes a new quarrying technique through which an inhabited hydrocommon is constructed over time. The project offers a new model for inhabiting wet environments, which brings human and ‘more-than-human’ inhabitants together.

17.17 Desire Lubwama, Y4 ‘The Wedding House’. Addressing issues of cultural, historical and ecological sustainability, the proposal is an adaptive space that explores applications of waste plastic, earth and clay to create temporally stable structures in the Tree Cathedral, Milton Keynes. The value of ritual is combined with material processing to re-engage the public and influence the design of these spaces.

17.18 Tia-Angelie Vijh, Y4 ‘MUR MUR’. Set within Bletchley Park, Milton Keynes, the project proposes to retrofit and restore the abandoned Block D – once home to the original codebreakers of World War II – into a quantum computer laboratory with exposed dilapidated courtyards. Through the use of historical and fictional text in relation to Block D and Alan Turing, the project proposes a series of adaptations, with the insertion of new courtyards and chambers.

17.19 Rebecca Lim , Y5 ‘Tempered and Timed Minimum Dwellings for Maximum Social Living’. Minimum dwellings, anchored by kilns and ovens for heating, making and sharing, extend Cosgrove Lakes holiday park in Milton Keynes. The post-digital architectural practice of drawing and machine learning critically reconfigures the notion of the conventional dwelling by seeing time and temperature as agents of social interaction. The dwelling is minimised through multiplicities of space but maximised for social exchange.

17.20 Matthew King , Y4 ‘Traces of Rhythm’. The scheme nestles where techno, Neolithic tradition and woodland management converge. By exploring these themes through the notation of cyclical processes, the scheme looks to uncover natural rhythms that bind us to the landscape. By cross-programming a timber yard with a rave site, the architecture becomes a vessel for reassociating young people in Milton Keynes with the landscape, instilling a sense of care.

Mind, body and environment is a shared continuum: an integrated reality in which architecture plays a transformative role.

PG17 started the year by visiting the astonishing landscape of Avebury, Wiltshire, with an aim to think about the value of largescale architectural events, human movement, earthen construction, sustainability and longevity. Avebury physically manifests 5,000 years of continuous human history: it includes the biggest man-made prehistoric mound in Europe and the world’s largest prehistoric stone circle, which encompasses a living village. These monumental earthworks were constructed collectively as public theatres for ceremonies. The act of building brought communities together and gave physical expression to their ideas.

PG17 promotes a collaborative understanding of architecture and seeks to nurture future generations of architects who will influence the world differently, precisely because of the pluralistic underpinning of their practices. Creative autonomy is vital but how do we nest it in collective purpose? We seek to amplify the role of the individual in a collective but also the role of collaboration in one’s own imagination and critical thought process.

We have a profound interest in the spaces and experiences we create when we become immersed in the act of design. As an embodied and extended action, design is able to diffuse and transform individual thought: it can distribute the mind to body and hands, offload it to tools and materials and, through these, continuously energise itself, making new and reciprocal connections with other minds, actions and technologies in the world. Design, in this way, becomes shared world-building.

Ethical values cannot be separated by aesthetic values. It would be unfortunate if the potential of mythos (story and mood) was weakened under the instrumentalism of logos (reasoning). In The Periodic Table (1975), the chemist and novelist Primo Levi interweaves materials and human events in a sequence of 21 short stories, each one dedicated to a chemical element, including ‘Carbon’, ‘Gold’, ‘Iron’ and ‘Uranium’. It is in a similar way that this year we all tried to explore the limits and altering states of different resources and the continual interdependence between material and cultural events in time. In accordance with Herman Hertzberger’s view that ‘the world is tired of all that architecture on steroids’,1 many of us chose to work purposefully with fewer means.

Year 4

Daeyong Bae, Zhongliang Huang, Rebecca Lim, Kaye Song, Negar Taatizadeh, Ella Thorns, Janet Vutcheva

Year 5

Pravin Abraham, Ross Burns, Ho (Jackie) Cheung, Thomas Dobbins, Naysan Foroudi, Nikolina Georgieva, Yangzi (Cherry) Guo, Hyesung Lee, George Newton, Benedicte Zorde Rahbek

Technical tutors and consultants: James Daykin, Sophia McCracken, Sal Wilson

Critics: Anthony Boulanger, Barbara-Ann CampbellLange, Nat Chard, Sandra Coppin, Kate Davies, Beverley Dockray, Elizabeth Dow, Murray Fraser, Maria Fulford, Clara Kraft, Perry Kulper, Chee-Kit Lai, Guan Lee, Anna Liu, Emma-Kate Matthews, Ana MonrabalCook, Shaun Murray, Stuart Piercy, Michiko Sumi, Phil Tabor, Peter Thomas, Robert Thum, Sumayya Vally, Victoria Watson, Oliver Wilton, Fiona Zisch

Circle of Friends: Malina Dabrowska, Nefeli Eforakopoulou, Katherine Hegab, Andreas Müllertz, Jack Newton, Danielle Purkiss, Julia Schütz

Guest Speakers: Alice Brownfield, Matthew Barnett Howland, Joshua Pollard, DJERNES & BELL, Local Works Studio, Studio Elements, THISS

B-Made: William Victor Camilleri, Tom Davies, Donat Fatet

1. Herman Hertzberger (17 September 2020), ‘Letter to a Young Architect’, The Architectural Review

17.1 PG17 ‘Circle’. A collaboration between all 17 students within the unit, where machine-carved oak blocks are brought together to form a single circle. Building upon the idea of community, which has given the Neolithic stones of Avebury, Wiltshire, such presence and importance throughout millennia, each piece denotes the essence and context of our projects. While their sites are scattered across the world, they are all brought together through the act of collaboration, creating a shared continuum. The work embodies our belief that the individual author finds significance and value within a collective purpose, expanded and remembered through time.

17.2 Hyesung Lee, Y5 ‘Extended Heritage’. Exploring a community’s relationship with architecture, ritual and fire, the project proposes a festival within the Avebury Stone Circles, held on the summer solstice, at which temporary structures and human activity revive the circle’s periphery. Repeated acts of burning and re-building challenge the popular, passive understanding of heritage.

17.3 Benedicte Zorde Rahbek, Y5 ‘Tower of Women’. Bringing a new agenda to the London skyline, the project is shaped and informed by historical and present-day female makers of society, arts and architecture. The design is experienced through shifts in time and light, creating an ever-changing scene where women collaborators continue to evolve and impact the design of the building.

17.4 Thomas Dobbins, Y5 ‘Time in Elmet’. A temporal study of the Upper Calder Valley, West Yorkshire, undertaken across three scales of understanding: human, material and industrial. Using a performative design methodology inspired by the processes of three local artists, a series of scored landscape explorations suggests a new civic infrastructure and writer’s retreat along the boundary of a village churchyard.

17.5 Nikolina Georgieva, Y5 ‘Of Fells and Thwaites’. The project develops a deep understanding of the anthropogenic landscape, interrogating its formative human and ecological practices. Located within the glacial, volcanic terrain of the Lake District, a wellness retreat distils qualities of the climatological, geological and worked taskscape and the mentally navigated landscape of the region.

17.6, 17.12 Negar Taatizadeh & Kaye Song , Y4 ‘The Fyfield School of Land’. Advocating for a re-engagement with our land, the project proposes a campus for hands-onlearning set within an area of Wiltshire’s farmland, with a 6,000-year history of cultivation. A purposeful system of collaboration creates a dialogue between two designers and their respective buildings, promoting a mindful approach to a landscape and its surroundings.

17.7 Janet Vutcheva, Y4 ‘New Water Meadow’. Responding to the continued ecological degradation of England’s chalk streams, due to the climate crisis, the project proposes an infrastructural water network for restoring their health. It does so by harvesting, storing and draining rainwater, which helps support the ecology’s intricate webs of life.

17.8 Zhongliang Huang , Y4 ‘Garden Uranus’. Located in Dungeness – a former nuclear site on the coast of Kent – the project seeks to support the area’s rich ecology through the establishment of a bird sanctuary. Small buildings and low-rise walls made of local materials establish playful boundaries amongst pools of water and garden equipment, striving to confront the ecological decline caused by human and nuclear power at an architectural level.

17.9 Daeyong Bae, Y4 ‘With the Traces’. The project focusses on how traces of human activity left on built environments commemorate the everyday acts of those

who occupy them. Situated in Avebury, Wiltshire, the proposal redevelops an existing park home to accommodate a more social way of living, attuned to the temporal rhythms of life and death that are so present within the stones of its neighbouring Neolithic stone circle.

17.10–17.11 Ho (Jackie) Cheung , Y5 ‘Duologue Between Islands’. Revealing the lost cultural, social and political connections between a small quarrying village and the metropolitan city of Hong Kong, the scheme examines colonial practices of making and incorporates a material history that is found engraved upon its stoney site, it proposes a sculpting school and space for discussion that hopes to empower its local population.

17.13–17.14 Ross Burns, Y5 ‘Re-peating the Highlands’. This project investigates the potential for a system of environmental stewardship through practical and architectural interventions into the Class 5 blanket peat bog surrounding Corrour Station in the Central Highlands. It seeks to maximise the health of the bog by choreographing the relationship between peat, sphagnum moss, water, sound and human occupation.

17.15 George Newton, Y5 ‘The Public House’. Sited in Palmers Green, London, the project suggests an alternative future for The Fox – a now-deserted pub on Green Lanes, one of London’s longest and busiest roads. Once a key building within the community, a radical idea for urban living is proposed to break away from cellular systems of housing and work, dissolving the binary conditions of privacy within the suburb.

17.16 Pravin Abraham, Y5 ‘Revitalisation of Wisma Damansara’. Found within an affluent neighbourhood of central Kuala Lumpur, the project repurposes an existing concrete office block to create a series of transient shelters and spaces for teaching that serve the city’s marginalised homeless community. The project becomes part of a sustainable solution that promotes public dialogue and interaction.

17.17 Ella Thorns , Y4 ‘Growing Phrontistery’. A transitory space between early learning institutions and the forest, which responds to existing ecological and human cycles in symbiosis with each other. The structure and its population grow as time passes. The building augments the trees’ growth and enables inhabitation between branches, a choreography that follows the harmonies of the forest in correspondence with learning.

17.18 Rebecca Lim, Y4 ‘Avebury Seed Barrow’. Set within the Neolithic and agricultural context of Avebury, Wiltshire, the project proposes a seed bank that re-appropriates the preservative notions of the Neolithic long barrow. It uses a dialogue of design practices between human and machine minds to question the generative potentials of drawing and visual media, highlighting the importance of interpretation within architecture.

17.19 Naysan Foroudi, Y5 ‘The Quad’. Positioned in a single field at the intersection of four competing worlds, the project negotiates the often complex, juxtaposed realities of the Salisbury Plain, Wiltshire. The design of a new civic space creates a dialogue between military, historic, residential and agricultural communities, working within the confines of a square to create an integrated approach allowing for the landscape’s diverse multiplicity.

17.20 Yangzi (Cherry) Guo, Y5 ‘Snowdonia Nocturne’. The project focusses on the transient journey of ascent from the Welsh town of Blaenau Ffestiniog to the site of slate ruins on the mountaintop plateau within a Dark Sky Reserve. It operates around diurnal and nocturnal cycles, and provides retreats for those who wish to restore their circadian rhythm and sensitivity to natural light.

PG17 is an experience-based learning and design environment which fosters the role of autonomy and collaboration equally in architecture, encouraging our students to produce work inside and outside the university, both as individuals and as groups. For us, the connection between architecture and experience not only exists in the relationship between building and life, but is also played out within the process of design itself. The Latin word experimentum reminds us that experiment and experience are twinned: to experiment is to experience through practice.

We are inspired by the ethos of Black Mountain College, where architect Buckminster Fuller, artists Anni and Josef Albers, composer John Cage and choreographer Merce Cunningham developed highly influential practices within a non-hierarchical and experimental learning community. We attempt to find an equivalent form of architectural pedagogy today.

While the unit supports individual whole-year projects, we also encourage working in ensembles. ‘Ensemble’ means a mix of separate things, actions and people, together forming a shared whole. For example, this year we stayed in La Tourette, where we produced a large collaborative drawing responding to Le Corbusier and Xenakis’ breathtaking building. Collectively, we turned drawing into an embodied action of site performance.

Accepting that no single governing author or approach can handle the complex environmental and social conditions we face, and recognising that architecture is a composing act, able to synthesise different considerations, we ask what role can an ‘architectural score’ play in enabling design ensembles and polyphonic structures? Scores aim to describe a process; they are works in themselves but also preparatory pieces for influencing further work. Time is the essential element of the score, through which relationships between parts are constructed. Open scores allow us to invent and adapt relations, both temporally and spatially. Just as a musical score can organise sonic space in time, so an architectural score can structure time, materials and relations in space.

The architectural score can unlock new methods of communication, production and inhabitation in architecture, encouraging much-needed slippages between people, materials, tools and ideas. It can mix times past with times future, and human skill with other forms of intelligence, in unexpected ways. Through open scoring, we can associate and disassociate the parts of an ensemble, to create an architecture that while evoking oneness and inclusivity, may also be contradictory.

Year 4

Pravin (Richard) Abraham, Ross Burns, Hoyin (Jackie) Cheung, Thomas Dobbins, Naysan Foroudi, Nikolina Georgieva, Cherry Guo, Hyesung Lee, George Newton, Benedicte Zorde Rahbek

Year 5

Eleni Efstathia Eforakopoulou, Veljko Mladenovic, Iman Mohd Hadzhalie, Ioannis Saravelos, Philip Springall, Harriet Walton

Thanks to our Design Realisation tutor James Daykin and to our consultants Nathan Blades, Sarah Earney, Sophia McCracken, Richard Mildiner, Eric Nascimento

Many thanks to our critics Kirsty Badenoch, Ruth Bernatek, Peter Bertram, Anthony Boulanger, Barbara-Ann CampbellLange, Nat Chard, Hannah Corlett, Sebastian Crutch, James Daykin, Sean Griffiths, Perry Kulper, Emma-Kate Matthews, Jörg Mayer, Niall McLaughlin, Thomas Pearce, Alex Pillen, Bob Sheil, Emmanouil Stavrakakis, Timothy Waterman, Victoria Watson, Patrick Weber, Simon Withers

Thanks to Laura Mark and Matei Mitrache

17.1–17.2 PG17 ‘Drawing La Tourette’. In January PG17 joined the Dominican community in La Tourette where students drew individually and collectively. This large inhabitable drawing was done collectively on the floor of the dining hall, and measures 3 metres x 5 metres.

17.3 Veljko Mladenovic, Y5 ‘Plum Puddin Island’. In this project, the found object and the landscape are pertinent to the understanding of architecture. Low-lying buildings and playfully-swept roofs are in play with flat field and windswept trees. Historically popular with artists and craftsmen, Thanet is once more attracting creative thinkers. Imagined as a crafts retreat, the programme is comprised of textile and woodworking workshops, a gallery, a tea room and nine residences.

17.4 Philip Springall, Y5 ‘Carlisle Alzheimer’s Foundation’. This project proposes a network which connects individuals in creative practice with individuals at various stages of Alzheimer’s disease. By developing creative partnerships, the pair can engage in meaningful activities to respond to the challenges of personal identity, occupation, responsibility and inclusion faced by those with Alzheimer’s. Situated in the centre of Carlisle, the proposed scheme is designed through creative activities of making, constructing, performing, eating, cooking, wandering, conversing and socialising.

17.5 Cherry Guo, Y4 ‘The Inland Pier’. Located on the seafront of Pegwell Bay, Thanet, this project proposes an ‘inland pier’ with a school that celebrates the craft of stone masonry, whilst exploring the possibilities of stereotomic assemblage. Serving as a mediator between the land and the sea, the scheme aims to create a continuous geology with a series of interconnected chalk passageways and projective spaces.

17.6 Hoyin (Jackie) Cheung, Y4 ‘Reconciling the Terroir: Inhabiting Seaweed’. This project challenges the role of nature in the urban context of Margate. It uses seaweed as a natural material, and integrates it into both the programme and the architectural tectonics to create dynamic interactions between the coast, the building and our sensory experiences within it.

17.7 Eleni Efstathia Eforakopoulou, Y5 ‘Winds of Marseille’. At a time of climate crisis, this project aims to understand the invisible choreography of the natural world as a basis for architecture. The proposal reuses the site of a disused acid factory, situated amongst the limestone foothills to the south of Marseille. It establishes a new settlement for a wave of people forced to leave their homes due to the effects of desertification in North Africa. It follows the site’s logic, organised around the prevailing winds, the sea, and the land contours.

17.8 Ioannis Saravelos, Y5 ‘The Walking School of Stackpole’. This project addresses the sociodemographic issues that face the dispersed communities of Pembrokeshire. It proposes a framework of interconnected walking schools that seek to re-establish the connections between the communities and the landscape. Through the use of novel digital media, the project provides translocational connections between the schools themselves and their local context.

17.9 Benedicte Zorde Rahbek, Y4 ‘The Lido’. The old abandoned lido on the edge between land and sea tells the story of the heyday of Margate as a traditional holiday destination, and the decline which so quickly struck and demolished the town’s livelihood. It holds great emotional value for the people of Margate. This project experiments with a way of developing a transformational language embodying the emotional content to come.

17.10 Iman Mohd Hadzhalie, Y5 ‘Towards the Sea: A Refugee and Conservation Centre for Cliftonville’. This project is set in the Northdown Road conservation area, exceptional for its poverty and population of migrant business owners. The proposal encourages

the further integration of refugees, teaching the skills of conservation of historic shopfronts. Through framing the sea, it gives a sense of nostalgia to the landscape by which refugees have crossed to their new community.

17.11 Nikolina Georgieva, Y4 ‘Mosaic of Earthworks’. By establishing an understanding of everlasting translation in the practices of archaeology and geology, this project proposes alternative ways of reading the land on which we built. The proposal for an archaeological centre on the coast of Stonar Lake, Thanet, engages with processes of soil pigmentation and ground excavations, to shape cultural landscape, growing as a mosaic of earthworks.

17.12 Ross Burns, Y4 ‘The Xenakis Institute’. This project celebrates the multidisciplinary techniques of the prolific architect, composer and polymath Iannis Xenakis. Inspired by his scoring methods and investigations into sound and experience through drawing, the proposal for a research, education and performance facility in the tranquil setting of Domaine de la Tourette, France, is a result of the role of music in its design process.

17.13 Hyesung Lee, Y4 ‘The Waste Archipelago’. This proposal aims to revive a once-ludic Margate by restoring its forgotten spaces. Abandoned buildings of the city become material quarries and the collected waste is reused to manufacture new objects that slot into neglected spaces, creating an archipelago of expanded public islands. Not only playful installations, but resourceful places where further material dérive creates the vibrant network of the Magic Circle of Margate.

17.14 Harriet Walton, Y5 ‘The Village’. This proposal is set in the rural community of Pembrokeshire village of Little Haven. Although tourism provides a large economic boost to the area, the village is losing its heritage and stories. The project proposes an integrated film studio and set of theatre spaces, in which the performance documents the lives of the village. The stories of the settlement become the plot, and the villagers the actors.

17.15 Pravin (Richard) Abraham, Y4 ‘The Chalk Amphitheatre’. Drawing upon Kent’s rich history of quarrying, the idea of excavating the remnants of an abandoned Lime Quarry in the village of Peene was pursued. The project looks at quarrying of chalk as process for shaping the landscape. Resulting in a unique musical ground, excavated into the earth, the proposal pushes Folkestone’s musical endeavours forward.

17.16 George Newton, Y4 ‘Manual’. The Cliftonville Lido is a lost centre of faded tourist industry in the heart of Margate. The resuscitation of this landmark is both an educational and political opportunity. By involving the community in the process of architectural conception, construction, inhabitation, and obsolescence, locals can acquire key trades and design skills, and forge their own space within the shell of the Lido.

17.17 Thomas Dobbins, Y4 ‘The Wantsum Assembly’. Confronting the complex relationship between the ecological and the human, the Wantsum Assembly is a transient citizens’ assembly for the people of Kent, where local environmental policies are created and debated. Funded by the drying of its timber-stacked walls, and disassembled after 15 years, the architecture becomes a physical and temporal embodiment of the discussions that have occurred within it.

17.18 Naysan Foroudi, Y4 ‘The Wantsum Common House’. A new form of architecture, inspired by the process of slip-casting and in tune with the natural rhythm of material accumulation, provides a place of collective gathering and shelter as the region changes. Spaces for conversation and meeting are formed around a series of baked in-situ hearths. Over time, the architecture gives way to a wider community participation, as new heritage trails, village fêtes and practices begin to take form.

Yeoryia Manolopoulou, Níall McLaughlin

Our ‘deep past’ is inscribed on our consciousness and holds the key to our modes of perceiving, reasoning and acting within social settings. Even as we wonder about the challenges and possibilities of the far future, we are using cognitive tools which evolved over millions of years. PG17 is interested in the experience of design itself: that is, the design of the activity of design as an embodied action evolving in time and place. It is the very event of drawing and making, whilst being in the midst of it, that we interrogate, enrich and celebrate. Lines tell stories and cross each other as we strive to produce architecture with public meaning.

Mind and environment have evolved side-by-side for millennia. Architecture has not only emerged from this dynamic partnership but, to different extents, has influenced and determined the relationship between our consciousness and surroundings. If architecture is a mediator between a community and its buildings, how can it flourish in a new post-digital social condition? The human mind has not been devised as a discrete, logical computational apparatus, instead, it is an evolved biological network fully immersed in its physical and social environment. To understand our opportunities and needs as architects, we must fully explore this distinction.

This year, the unit investigated mind, community and land within time extremes. Our research and design processes were influenced by prehistory, anthropology, cognitive psychology, geology and emerging climate sciences. We considered animal and plant life, climatic uncertainty, the politics of land and artificial intelligence.

We visited the Orkney Islands – an archipelago of over 70 islands in the north of Scotland – which have been inhabited for at least 8,500 years and were, several thousand years ago, Britain’s centre of innovation. We visited a vast hill covering more than six acres of land, which was thought to be made of glacial debris until, recently, it was discovered to have been made over 5,000 years ago by humans. Such enormous and timeless constructions on the Orkney Islands sit side-by-side with the newest facilities of wind and marine energy resources, stimulating a revived population of people who choose to live there. We worked intimately with this place, organising collective walks and drawing events.

Collaboration can break habits of mind, allowing other ways of seeing to influence our consciousness. Our drawing processes borrowed from modes of collaboration, performance, improvisation and chance in the aleatoric arts.

Year 4 Eleni Efstathia Eforakopoulou, Veljko Mladenovic, Iman Mohd Hadzhalie, Philip Springall, Harriet Walton

Year 5

Nathan Back-Chamness, Luke Bryant, Ossama Elkholy, Grace Fletcher, George Goldsmith, Hanrui Jiang, Rikard Kahn, Cheuk Ko, Alkisti Anastasia Mikelatou Tselenti, Andreas Müllertz

Thank you to Design Realisation tutors James Daykin and Maria Fulford

A special thanks to our critics: Barbara-Ann Campbell-Lange, Nat Chard, Hannah Corlett, Murray Fraser, Anne Marie Galmstrup, Pedro Gil, Agnieszka Glowacka, William Haggard, Tamsin Hanke, Chris Hildrey, Will Hunter, Susanne Isa, Sarah Izod, Matthew Leung, Anna Liu, Emma-Kate Matthews, Dean Pike, Sophia Psarra, Chenhan Wang, Tim Waterman, Victoria Watson, Izabela Wieczorek

17.1 PG17 Collaborative Drawing, Y4 and Y5 ‘Experiencing Landscapes’.

17.2 Nathan Back-Chamness, Y5 ‘Untitled’. Throughout this year-long project, the acts of doing and observing became a working method whereby architecture can be continually conceived and challenged, over thousands of years and within a single drawing.

17.3 Hanrui Jiang, Y5 ‘Fluidity between Land and Sea’. This project is based on the reading of Selkie – mythological ‘seal folk’ in Scotland – tales, which explore ‘fluidity’ within coastal regions. The site – the abandoned island of ‘Eynhallow’ – is investigated through its geographical features and the analogy that sealskin can be regarded as a transition between the land and the sea, and humans and seals. This study of ‘fluidity’ shapes the morphology of the island, reading the sea as a continuation of the land, with the water as only a thin membrane that separates the two.

17.4 Luke Bryant, Y5 ‘A Piece of Landscape’. This new intervention creates connections between isolated Neolithic monuments that were originally part of a processional path 5,000 years ago. ‘A Piece of Landscape’ seeks to interpret the historical sites, as well as engaging with the surrounding environment. Stones from Stromness –a nearby town at risk of flooding – are used to create a new structure; applying Neolithic principles to transport stones from previous communities across the landscape.

17.5 Alkisti Anastasia Tselenti Mikelatou Tselenti, Y5 ‘Orkney Tourism Association’. A series of archaeological studies of the scattered chambered cairns – Neolithic burial monuments – of the Orkney archipelago challenges the conventional understanding of ‘archives’. This project argues that in order to envisage an archive for the islands, the only honest representation is the archipelago itself. The proposal aims to bridge the fragmented temporal and spatial gaps of Orkney, as well as to shed light on its marginalised past.

17.6 Veljko Mladenovic, Y4 ‘Temporal Strata’. Located directly on top of the Ness of Brodgar – a key Neolithic site currently under investigation – this project is a ‘living archive’, and explores architecture as a continual process without an end. ‘Making in time’ is a key theme where, through a dialogue of chance and intent, unpredictability is replicated to manifest an open-ended architecture.

17.7 Eleni Efstathia Eforakopoulou, Y4 ‘Living Geologies’. The romantic and picturesque sceneries that we see today are not static but, rather, are the result of a slow-motion car crash. This project interrogates this violent choreography and has sought to reimagine the landscape as in a perpetual state of change.

17.8–17.9 Ossama Elkholy, Y5 ‘Copinsay’s Dark Uncanny’. Assuming landscape is a living process, this proposal plays out the impact of an imposed quarrying process, using a speculative quarrying tool that surveys Copinsay island’s geological, meteorological, economic and ecological data to inform its movement and digging. It proposes that people manually carve the remaining stone, responding to what has already been excavated, simultaneously observing the unfamiliar ecologies that emerge.

17.10 Rikard Kahn, Y5 ‘Birsay Refuge’. This project seeks to provide a place for visitors to stay on the island of Birsay, accessible at only the lowest point of the tidal cycle. Interweaving itself with the archaeological remains of earlier Pictish and Viking settlements, the proposal provides a place for longing, contemplation and communal living whilst taking refuge on the historic site.

17.11 Harriet Walton, Y4 ‘Bog Queen’. Set in the landscape of Hoy, the sub-function provides a refuge for walkers on the island, made though the excavation of the peat bogs that cut through the landscape. The building hosts a seasonal music festival, whereby material removed from the subterranean peat chambers is assembled into structures above the cuts. The seasonal awakening of the structure is carried out by island residents and visitors during the summer to form a music chamber. In autumn the structure is disassembled and repacked into the main chamber and is preserved for another year in the peat.

17.12 Iman Mohd Hadzhalie, Y4 ‘Slowly Dyeing’. Natural purple dye in Orkney has become increasingly scarce due to the scarcity of the endangered purple flora from which it is made. In response, this proposed mill produces natural dye using a traditional process of fermenting lichen, as an alternative, sustainable solution to using purple flora. The building rejuvenates the abandoned ruin of the Earl’s Palace, Birsay, connecting with the rich heritage of the Orkney archipelago whilst also creating a new future.

17.13 George Goldsmith, Y5 ‘Scapa Flow: An In-Situ Exhibition of Historical Knowledge’. This project explores ideas of exposing the unseen information stored within the islandscape of Orkney, and the amplification of nature and historical knowledge in the landscape. The project suggests a way of combining a museum and habitation with the need to generate renewable energy. The speculative proposal puts forward the idea that the exhibition of historical knowledge in-situ is superior to the removal of items from their context.

17.14 Grace Fletcher, Y5 ‘Stroma Salt Station’. This proposal seeks to regenerate the abandoned island of Stroma through the surrounding sea water and tidal energy of the Pentland Firth. The island has a dichotomous condition whereby the east is dry and fertile and the west is inhospitable and salty. A permeable membrane is constructed along the divide to enhance the existing differences, in turn setting up the island as a salt water battery for tidal energy. The battery accumulates in the centre of the island, in a power station built of salt and gypsum residue.

17.15 Philip Springall, Y4 ‘Leviathan’. The Stromness Maritime University reconnects the people of Stromness with the sea. Stranded whales, which are otherwise thrown into landfill, are transformed from raw material into building components, with each part of the whale utilised for its unique qualities. This whale tectonic combines bone, blubber, baleen, blood and oil into an inhabitable architecture.

17.16 Cheuk Ko, Y5 ‘Dynamic Body as a Measure and Projector for Architecture’. This project explores the conceptual relationship between the body and space, which is not necessarily recognisable on a daily basis unless intentionally examined. Actions, movements and processes are studied to design a farmhouse in Orkney, aiming to reintroduce pleasurable farming that reconnects the body and landscape.

17.17 Andreas Müllertz, Y5 ‘The Sea as a Room’. In this project, the Scapa Flow – a landlocked sea at the heart of the Orkney Islands – has been dammed and drained to reveal a vast landscape of shipwrecks, archaeological sites and scarred terrain. Timber infrastructure emerges from the practice of forestry under the previous water line, carrying boats and timber across the sea of trees.

Year 4

Nathan Back-Chamness, Luke Bryant, Grace Fletcher, George Goldsmith, Hanrui Jiang, Rikard Kahn, Alkisti Anastasia Mikelatou Tselenti, Andreas Mullertz, Cheuk Ko

Year 5

Jinman Choi, Ashley Hinchcliffe, James William Greig, Julia Schutz, Rebecca Sturgess, Sam Eu Tan, Krystal Ting Tsai

Thank you to our Design Tutors: James Daykin, Maria Fulford

Thank you to our critics: Jessam Al-Jawad, Peter Besley, Alastair Browning, Barbara-Ann Campbell-Lange, Joanne Chen, Hannah Corlett, Will Hunter, Jan Kattein, David Kohn, Anna Liu, Jack Newton, Stuart Piercy, Sophia Psarra, Sabine Storp, Michiko Sumi, Victoria Watson

We are grateful to our sponsors:

Allies and Morrison

James Latham

Stanton Williams

Architectural education is not merely a preparation for professional practice, in which skills and techniques are acquired in anticipation of the challenges of the working world. It constitutes a form of practice in its own right.

We believe that the concept of a seven-year warming-up period is untenable and that it is essential for students to put themselves forward as protagonists in the architectural discussions of their time. They should create experimental forms of practice that stand in a critical and enhancing relationship to the world of building. The teaching studio can test propositions in a critical culture that allows for flexible thinking, inventiveness and openness to failure, in a way which is impossible in professional practice. For this process to be effective, the studio practice must understand the realities of social, political and financial mechanisms, without necessarily accepting them. It is this discourse between the possible and the conceivable that is fertile ground for architectural speculation.

In order to act ambitiously, an architecture student would need to acquire a formidable range of skills from inside the discipline of architecture. A profound literacy in the architecture of the past and its continuing relevance to the future is a cornerstone of our discipline. Architectural plans and sections, for example, embody a way of thinking that belongs only to architecture. They give us our potency and authority among other languages and forms of production.

Unit 17 engages directly in issues that are relevant to the public life of our city now. In London, there has been a looming sense of crisis about the role of the architect and the relationship between construction expertise and public life. The mainstream media have openly questioned the role of architects in the creation of just and well-integrated urban communities. Architects are often seen as the cowed servants and tools of a dominant and predatory capitalist mode of production. They are equally accused of unrealistic forms of idealistic or liberal thinking, at odds with the realities of contemporary economy and construction culture. This alleged balance of powerlessness and impracticality is deeply corrosive to the discipline of architecture. Developers speculate that architecture might die out as a discipline, while architecture schools look to teach new specialisations, often undermining the expert knowledge of architecture itself.

Architecture in London has a fight on its hands. Our students have seen themselves as protagonists in this battle for relevance and influence. They have produced proposals for the area that stretches between Euston Station and Mornington Crescent, each student designing one building while considering the relationships between the site’s housing stock, public buildings, infrastructure, landscape and public space. How can different voices intermix successfully? How can architecture help create a just and equitable neighbourhood?

Fig. 17.1 James William Greig Y5, ‘Euston Terminus’. This project questions the HS2-led widening of the existing Euston Station, proposing instead a dual layer, 24-platform subterranean station, freeing the ground level to provide a large public space back to the city. The station takes on a phantasmagoric quality, creating poignance and significance at the point of arrival and departure into and out of London. Fig. 17.2 Rikard Kahn Y4, ‘Higher School’. The project seeks to define a new vertical school typology for the London Borough of Camden raised above the railway. Publicly shared functions are located at ground level, forming adjacent a new square, whilst private spaces, such as classrooms, are arranged above. The strategy allows the structure to be utilised beyond the typical school hours; a mere 14% of the calendar year.

Fig. 17.3 Nathan Back-Chamness Y4, ‘Euston Train Station’. The station is reimagined as a series of gridded streets with the concourse removed. Instead of going to the platform, the traveller finds an address within a piece of city, entering at street level and descending to the train carriage below ground. The node gives rise to an exploration of subterranean architecture. Fig. 17.4 Julia Schütz Y5, ‘The Drummond Street Weave’. This community proposal seeks to reconnect the people of Drummond Street. Lightweight, transformable timber components and tensile elements form a framework that is inhabited by a variation of spatial qualities. An architecture of changes offers flexibility and non-prescribed space. The principle of opposites acts as an underlying order.

Fig. 17.5 Krystal Ting Tsai Y5, ‘Institute of Behavioural Neuroscience: A Semi-Naturalistic Rat Lab’. The chosen brief is to design a new model habitat concerned with the welfare of rats in a neuroscience laboratory. The proposed research facility design focuses on the development of an evolving rat wall habitat providing a semi-naturalistic environment, around which human laboratory spaces conform. Fig. 17.6 Ashley Hinchcliffe Y5, ‘Ampthill Place: A Co-Housing Model for London’. A model for high-density co-housing alongside the train tracks. Offering a solution for the vast removal of earth by HS2, the housing rises out of clay to form a network of courtyards, intimate paths and flexible modules. Internally, it removes the corridor, proposing split-level circulation interweaving private and communal.

Fig. 17.7 Jinman Choi Y5, ‘Euston Cloud’. Above Euston Station, an adaptable system produces and contains a new model of shared economy, driven by interactive feedback from its inhabitants. Building elements, appliances and furniture are distributed to a range of accommodating spaces by the protagonist. The temporary occupation of these spaces forms a kaleidoscopic field of structure, system and use - a cloud.

Fig. 17.8 Grace Fletcher Y4, ‘Refurbishing the Towers at Ampthill Square’. Architecture is too often used as a scapegoat for political failure; demolished and replaced at great loss to the community. Instead, 240 residents will return to their homes to find interior courtyards, double-height spaces and collective vertical streets. Fig. 17.9 Cheuk Ko Y4, ‘Innerworlds’. The project reconsiders non-medical spaces in a cancer treatment centre, such as waiting rooms and healing gardens, as part of the healing process. Creating calmness and comfort through thresholds allows patients to temporarily forget what they are going through. Fig. 17.10 Hanrui Jiang Y4, ‘Existent Nonplace’. The project is located on the site of a historic burial ground that has developed rapidly due to its proximity to Euston Station. The proposed HS2 development offers an

opportunity to explore a mixed programme of transport infrastructure and housing, embracing natural light.

Fig. 17.11 Andreas Müllertz Y4, ‘Re-Establishing Euston Grove’. The Euston terminus is re-imagined as a green set-piece in a Nashian promenade extending north from Somerset House. The physical infrastructure takes the shape of a vaulted circus cloister, acting as a threshold between the subterranean platform spaces and a daylit pine forest at ground level.

Figs. 17.12 – 17.13 Rebecca Sturgess Y5, ‘Life of the Tolmers Tower’. On a site with a history of conflict between the community and developers, the provision of a new public square becomes the catalyst for the sequential construction of an incremental tower. The architect resides within the tower to orchestrate an iterative amalgamation of fragments.

Fig. 17.14 Luke Bryant Y4, ‘Past Best Before’. The project aims to provide a positive new identity for the residents of Ampthill Estate, who experience uncertainty about their future due to the HS2 expansion. The creation of a ‘past best before’ market, selling food that is still good for consumption, offers a cheaper alternative whilst responding to London’s food waste.

Fig. 17.15 Alkisti Anastasia Mikelatou Tselenti Y4, ‘The New Secondary School for Deaf Students in Euston’. The secondary school aims to create an educational environment with internal spaces designed to enhance visual communication through vertical openings and diagonal connections, while an alternative learning method - the peripatetic - is employed to shape the journey through the building. Fig. 17.16 George Goldsmith Y4, ‘A Reinvention of UCL Central Campus’. The proposal suggests

an alphabet of small architectural interventions which extrude through the heavy, domineering façades of UCL’s central campus, creating a dialogue between the faculties and increasing spaces of shared programmes. The new interventions and thresholds establish a coherent material and tectonic identity. Fig. 17.17 Sam Eu Tan Y5, ‘The Euston Ravine’. In challenging the decontextualised spatiality of the London Underground, The Euston Ravine offers the commuter an alternative route down to their platform, emphasising instead the deep physical earth one must traverse through, the transient condition of travelling, and the heurism it has the potential to incur, conflating the daily commute with larger arcs of movement in nature.

Year 4

Naomi Au, Jinman Choi, James Greig, Julia Scheutz, Mai Que Ta, Sam Tan, Esha Thapar, Krystal Tsai Ting, Torris Kaul Varoystrand, Alexander Wood, Eleni Zygogianni

Year 5

Malina Dabrowska, Juwhan Han, Carl Inder, Vasilis Marcou Ilchuck, Oscar Plastow, Henry Svendsen, Christie Yeung

Thank you to our Design Realisation Tutors James Daykin and Simon Tonks

Thank you to our invited speakers who introduced us to mathematical concepts related to philosophy, design and computation: Adam Beck, Mario Carpo, Sean Hanna

Thank you to Maciej Czarnecki, Edward Denison, Joanna Leman and Gdynia’s Foreign Relations Department for their support during our field trip in Poland

Thank you to our critics: Alessandro Ayuso, Julia Backhaus, Anthony Boulanger, Gillian Brady, Barbara-Ann Campbell-Lange, Nat Chard, Claire Chawke, Sophie Cole, Marjan Colletti, James Daykin, Lily Jencks, Anna Liu, Jack Newton, Jessica Reynolds, Henning Stummel, Peter Thomas, Mike Tite, Simon Tonks, St John Walsh, Victoria Watson, Mika Zacharias.

Consultants: William Whitby (ARUP), Hareth Pochee (Max Fordham)

2 3 5 7 11 13 17

Unit 17 takes a progressive and experimental approach to architecture that is specific to place and culture. Our work develops through open inquiry. It is founded on the recognition that the architect works both as scientist and poet, being equally engaged in empirical analysis, abstraction, speculation and invention.