Design Anthology PG24

Architecture MArch (ARB/RIBA Part 2)

Compiled from Bartlett Summer Show Books

Architecture MArch (ARB/RIBA Part 2)

Compiled from Bartlett Summer Show Books

At The Bartlett School of Architecture, we have been publishing annual exhibition catalogues for each of our design-based programmes for more than a decade. These catalogues, amounting to thousands of pages, illustrate the best of our students’ extraordinary work. Our Design Anthology series brings together the annual catalogue pages for each of our renowned units, clusters, and labs, to give an overview of how their practice and research has evolved.

Throughout this time some teaching partnerships have remained constant, others have changed. Students have also progressed from one programme to another. Nevertheless, the way in which design is taught and explored at The Bartlett School of Architecture is in our DNA. Now with almost 50 units, clusters and labs in the school across our programmes, the Design Anthology series shows how we define, progress and reinvent our agendas and themes from year to year.

2024 Adaptation

Penelope Haralambidou, Michael Tite

2023 It’s About Time

Penelope Haralambidou, Michael Tite

2022 Vibrant Matter

Penelope Haralambidou, Michael Tite

2021 Wanderlust

Penelope Haralambidou, Michael Tite

2020 Guilt Free

Penelope Haralambidou, Michael Tite

2019 Redrawing the Rural

Penelope Haralambidou, Michael Tite

2018 Sculpting in Time

Penelope Haralambidou, Michael Tite

2017 Make-Believe

Penelope Haralambidou, Michael Tite

2016 Against the Flow

Penelope Haralambidou, Simon Kennedy, Michael Tite

2015 Forty Second Island

Penelope Haralambidou, Simon Kennedy, Michael Tite

2014 Remember the Future

Penelope Haralambidou, Simon Kennedy, Michael Tite

2013 Collisions

Michael Chadwick, Simon Kennedy

2010 Possibilities of Exchange: Poetic Transference

Uwe Schmidt-Hess, Michael Wihart

2009 Migrating Thresholds

Uwe Schmidt-Hess, Michael Wihart

2006 Phenomenal Noumena: extreme PHENOuMENA

Steve Hardy, Jonas Lundberg with Ken Faulkner

2005 Effectual Formalisms

Steve Hardy, Jonas Lundberg

2004 [Bosphorus] Drifts [Caspian] Shifts

Peter Hasdell, Patrick Weber

Penelope Haralambidou, Michael Tite

PG24 is a group of architectural storytellers employing film, animation, VR/AR and physical modelling techniques to explore architecture’s relationship with time. We are in search of bold new narratives to help us make sense of the complexity of today’s world.

Adaptation is a term with a multiplicity of meanings. A key term in evolutionary theory, biological adaptation describes the mutations necessary for creatures to adapt to their environment. Adaptation in the arts has a long tradition of converting one type of work to another, from a novel to a screenplay. In architecture, it has gained prominence in the growing need for adaptive reuse of existing buildings, as a combination of urgent crises like climate change and resource scarcity makes building anew a thing of the past. Furthermore, developments in digital technology and AI demand a post-human, lightning-speed adaptation to a new hybrid physical/digital spatial order.

This year we made ‘adaptation’ our primary focus. We explored the material, philosophical and sociopolitical dimensions of adaptive reuse, by grafting new designs into the long history of older buildings and employing the storytelling potential of all other forms of adaptation in architectural design.

Our work was informed by three designer strategies: ‘Defining a Host’, a building, structure or urban spatial condition (existing, demolished or fictional) which was surveyed, filmed, occupied and subjected to a deep material and historical analysis; ‘Developing a Graft’, the introduction of a new programme, narrative, community or material into the host; and ‘Composing an Evolution’, combining traits of the host and the graft into a holistic design through long-term thinking and duration, allowing them to mutate into new adaptations unfolding in time.

From Eugène Viollet-le-Duc to Lacaton & Vassal, architecture in the Francophone regions of Northern Europe has a deep tradition of reuse and reinvention. In January, we travelled to Paris to examine historically important adaptive reuse buildings and their legacy.

Notions of adaptation eschew the idea of a single central master designer, requiring generosity and a willingness to engage with found conditions in a negotiation with the past. The ability to adapt could be the hallmark of all future architects.

Year 4

Daniel Collier, Joel Gallery, Tristan Hubbard, Jason Lai, Daniel Langstaff, Yuchen Wang

Year 5

Maciej Adaszewski, Jean Jacques Bell, Weiting (Terry) Chen, Zixi (Vito) Chen, Ryan Darius, Beatrice Frant, Yixuan (Aurelia) Lu, Joshua Nicholas, Ewan Sleath, Mārtiņš Starks

Technical tutors and consultants: Matthew Lucraft, Bola Ogunmefun, Julia Torrubia

Thesis supervisors: Alessandro Ayuso, Camillo Boano, Gillian Darley, Paul Dobraszczyk, Oliver Domeisen, Luke Pearson, Rokia Raslan, Oliver Wilton, Guang Yu Ren

Critics: Matthew Butcher, Krina Christopoulou, Marjan Colletti, Camille Dunlop, Paris Gazzola, Gabriele Grassi, Kostas Grigoriadis, Jan Kattein, Jakub Klaska, Greg Kythreotis, Tony Le, Stefan Lengen, Matthew Lucraft, Yeoryia Manolopoulou, Sonia Magdziarz, Loukis Menelaou, Matei Mitrache, Luke Pearson, Joshua Richardson, Javier Ruiz, Matthew Simpson, Sayan Skandarajah, Jasper Stevens, Jonathan Tyrrell, Tom Ushakov, Nasios Varnavas, Tom Ushakov

24.1 Maciej Adaszewski, Y5 ‘The Testimony of Huaraz Valley’. The project explores legally representing non-human Andean entities – specifically the sacred Palcaraju glacier in Peru – through embodying local mythologies and architecture as magical realism. It examines the profound ecological impacts of land exploitation on communities facing environmental crises like global warming, glacier retreat, dangerous lake formation and water scarcity affecting the Huaraz Valley. By researching the history of Andean land extraction and translating insights into a fictional film across timelines, the project amplifies these communities’ scenarios and contributes to the discourse on pluralism and environmental reciprocity. The magical realist approach blends myth with the built environment to advocate for the legal rights and protection of sacred non-human entities.

24.2 Ryan Darius, Y5 ‘Batam’s Data Centre’. The exponential growth of digital data worldwide has driven an increasing global demand for digital data storage, leading to the construction of data centres in developing countries. Within the framework of a neoliberal economy, the intricacies of data storage manifest as a territorial dispute, hinging on the evaluation of which regions are deemed less valuable in terms of economic development.

Acknowledging the inevitability of globalisation, this project explores an innovative approach to modern data centre design by proposing a typological merging of traditional fishermen’s dwellings with modern data centres in Batam, Indonesia. By closely studying vernacular architecture and utilising simulation modelling to generate geometries based on the local climate, this project rethinks data centre design with a focus on local culture and passive design principles.

24.3–24.5 Jean Jacques Bell, Y5 ‘The Stewartby Printworks’. The project mourns the loss of the last four iconic chimneys of Stewartby Brickworks in Bedfordshire. Instead of demolishing the chimneys, the project proposes a new legacy for the site where developers, the community and the architect come together to create something meaningful for the adjoining model village of Stewartby. Critiquing current development methods and utilising emerging additive manufacturing technologies, a 3D-printed housing test bed is proposed to address the current challenges facing the UK housing sector. To facilitate this demand, the unique local clay was tested and printed to realign the site’s rich material culture with the modern age and develop a site-specific hierarchical block construction method.

24.6 Zixi (Vito) Chen, Y5 ‘Wuhan Archaeology for Revolution’. The future of Wuhan, China, lies in its ignorance of the world hidden beneath it. The scenes seen there today reside between reality and delusion; they are all built upon the ruins of the past. Soon, they will become part of it. Defining a Chinese city is a difficult task, but in this project, the adaptation to the history of Wuhan began by searching for lost memories. It has undergone demolition, just like the fate of the city. A revolution once reduced Wuhan to ashes. Whether such destruction will happen again in the future, the answer is hidden in the story that the final film of this project unfolds.

24.7–24.9 Weiting (Terry) Chen, Y5 ‘Finding Formosa’. This innovative architectural project, was developed as a ‘graft’ to both support and challenge the historic buildings on Dihua Street, Taipei. As preservation issues with the currently repurposed heritage site emerged, the architecture was redesigned to decolonise and safeguard Taiwan’s history. This is achieved by preserving and showcasing architectural remnants from various eras of Taiwanese history through diverse methods that enhance appreciation and interaction with the heritage.

The film chronicles a journey over the past year to learn more about Taipei and Taiwan, the birthplace of the protagonist. It takes place in the protagonist’s dream, where he is guided through the building by various voices corresponding to the spaces, each representing a distinct period of Taiwanese history.

24.10 Ewan Sleath, Y5 ‘IDEGO’. This isometric roleplaying game is set in a scavenger settlement built over a drifting oil platform after a global climate collapse. The player explores two realms within the game: the ‘Above’, a ruined reality of planetary flooding and scavenged architecture, and the ‘Below’, an ephemeral space embodying a psychic reflection of characters. Through in-game design and construction, the player’s creation of a salvagepunk vessel aboard the rig can be enhanced through a sequence of quests, leading them to the labyrinthine architecture below. There, they find clues about their fellow survivors, helping them to understand them better and ultimately earning their trust and help. The project reflects on the convergence of video game design with architecture and mixes handcrafted character creation with procedural generation.

24.11–24.13 Yixuan (Aurelia) Lu, Y5 ‘Kyoto’s Adaptive Reverie’. In response to the endangered status of Kyoto’s iconic timber townhouses, the project redefines the architectural typology of machiya (traditional Japanese wooden townhouses) and their dual role as both cultural heritage and residential dwellings. The housing initiative delves into the essence of machiya, while acknowledging modern-day challenges, and transforms these traditional structures into adaptable, sustainable and flexible solutions for urban living. The design narrative is steered by a fictional Japanese character in the year 2054, who spearheads a housing cooperative scheme in honour of her lost childhood home. By purposefully setting the timeline in the future, the programme is conceptualised retrospectively, with the narrative designed to revitalise machiya and ensure the typology remains relevant.

24.14 Beatrice Frant, Y5 ‘The Domestic Alien’. Developed as a three-act play set between Bucharest and London, the theatrical set defines the female psyche as a tangible way to inhabit domestic architecture. The project addresses the lack of belonging in familiar spaces, using ficto-critical narratives to visualise the alienating experience. It analyses sociopolitical situations in which women felt confined by their homes, combining transformative structures with accurate site portrayals. Additionally, the project proposes a visual reinterpretation of the female body as an othered ‘alien’ through the use of inflatables. By choosing the kitchen, the bedroom and the bathroom to depict the stage set, it questions whether buildings can respond to the specific psychological needs of a woman/alien.

24.15–24.18 Mārtiņš Starks, Y5 ‘An Ark of Us’. The project is an inquiry into architectural worldbuilding as a tool for weaving between local and global narratives. It traces the birth and decay of a fictional cosmic dream, emerging from Latvia on the fringes of the Western world. Navigating themes of Soviet heritage and post-Communist optimism, the Baltic Space Laboratory unfolds across both its Earth and lunar sites. Steeped in local folklore, the imagined moon base inscribes traces of its ecological and cultural origins into the barren landscape. The project envisions six lunar habitats, each centred around a totem symbolising the Earth’s essence, blending practical functions with spiritual elements. The mission focuses on preservation, reflecting the human drive for memorialisation and storytelling.

Penelope

PG24 is a group of architectural storytellers employing film, animation, VR/AR and physical modelling techniques to explore architecture’s relationship with time. We are in search of bold new narratives to help us make sense of the complexity of today’s world. Despite its omnipresence, time is often sidelined in design thought – overlooked by more prominent questions of aesthetics, budget and risk. Introducing time as a fundamental agent in design thinking can unfold a chronicle of assembly; predict a structure’s response to weather; calculate future patterns of occupation; introduce sound and relink architectural composition with music; offer an amplified sense of inhabitation and empathy; and connect with history and imagine the future. Long-term thinking helps us to consider the entire lifecycle of a building, from its conception to its death. Moreover, our highly mediated and interconnected world appears to accelerate the need for urgent social and environmental action. A sense of crisis looms daily: we are too ‘slow’ in our response to the climate emergency; our ‘fast-paced’ lives are overly dependent on carbon-intensive activity; inequalities seem to be deepening ever more quickly. Are we simply running out of time?

This year PG24 questioned time and its scientific, philosophical, psychological and political constitution. Are our global conventions of measuring time entrapping us? Can we escape international time and the hegemony of the clock? Can we find alternative temporal systems and different ways of being in time? Can design help us become better attuned to planetary movements and the circadian rhythms of our bodies? What is the architecture of uchronia, the temporal utopia?

This year’s brief stops to reflect on how a deeper consideration of time, duration and speed might trigger bolder and more effective solutions to problems that confront our bodies, cities, landscapes and technosphere. In November we took a field trip to the Netherlands and visited the 10th Architecture Biennale Rotterdam, titled It’s About Time, from which we took our inspiration. The students’ work was informed by the exhibition’s formulation of three main designer strategies based on different velocities of change: the Ancestor, the Activist and the Accelerator. The unit defined 2072, 50 years from now, as a chronological orientation point that united all our projects.

Year 4

Maciej Adaszewski, Jean Bell, Weiting Chen, Zixi Chen, Ryan Darius, Beatrice Frant, Rachel Livesey, Yixuan Lu, Joshua Nicholas, Nikoleta Petrova, Ewan Sleath, Mārtiņš Starks

Year 5

Loukis Menelaou, Cira Oller Tovar, Joshua Richardson, Matthew Semião Carmo Simpson, Chak Ming Anthony Tai

Technical tutor and consultant: Matthew Lucraft

Thesis supervisors: Alessandro Ayuso, Tim Lucas, Sophia Psarra, Oliver Wilton, Stamatis Zografos

Critics: Vitika Agarwal, Laura Allen, Uday Berry, Matthew Butcher, Nat Chard, Marjan Colletti, John Cruwys, Edward Denison, Camille Dunlop, Jack Holmes, Pedro Gil, Kostas Grigoriadis, Will Jefferies, Daniel Johnston, Matthew Lucraft, Emma-Kate Matthews, Matei Mitrache, Giles Nartey, Caireen O’Hagan, George Proud, Sophia Psarra, Elly Selby, Jonathan Tyrrell, Tom Ushakov, Sandra Youkhana, Fiona Zisch

24.1–24.2

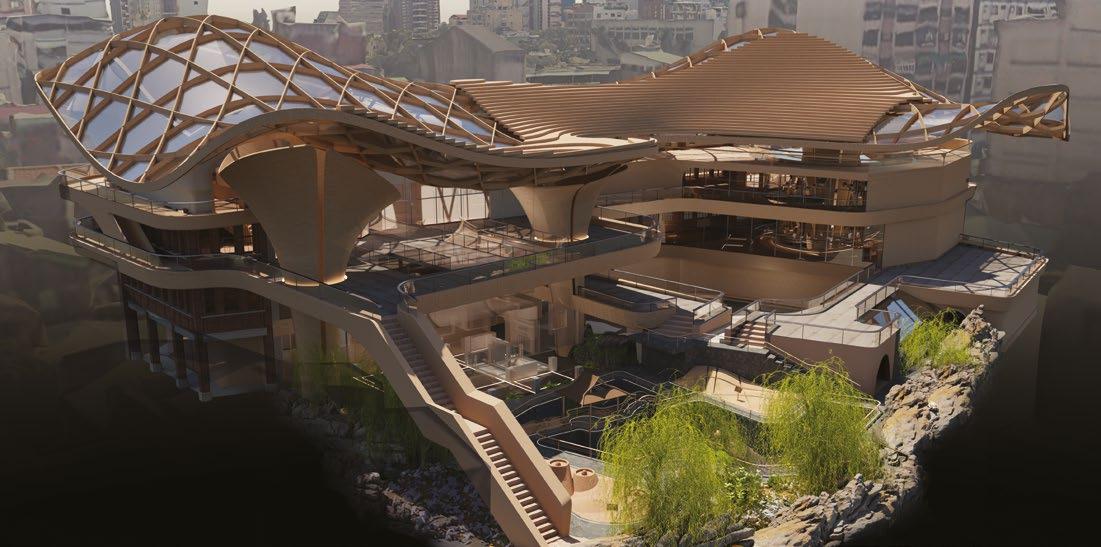

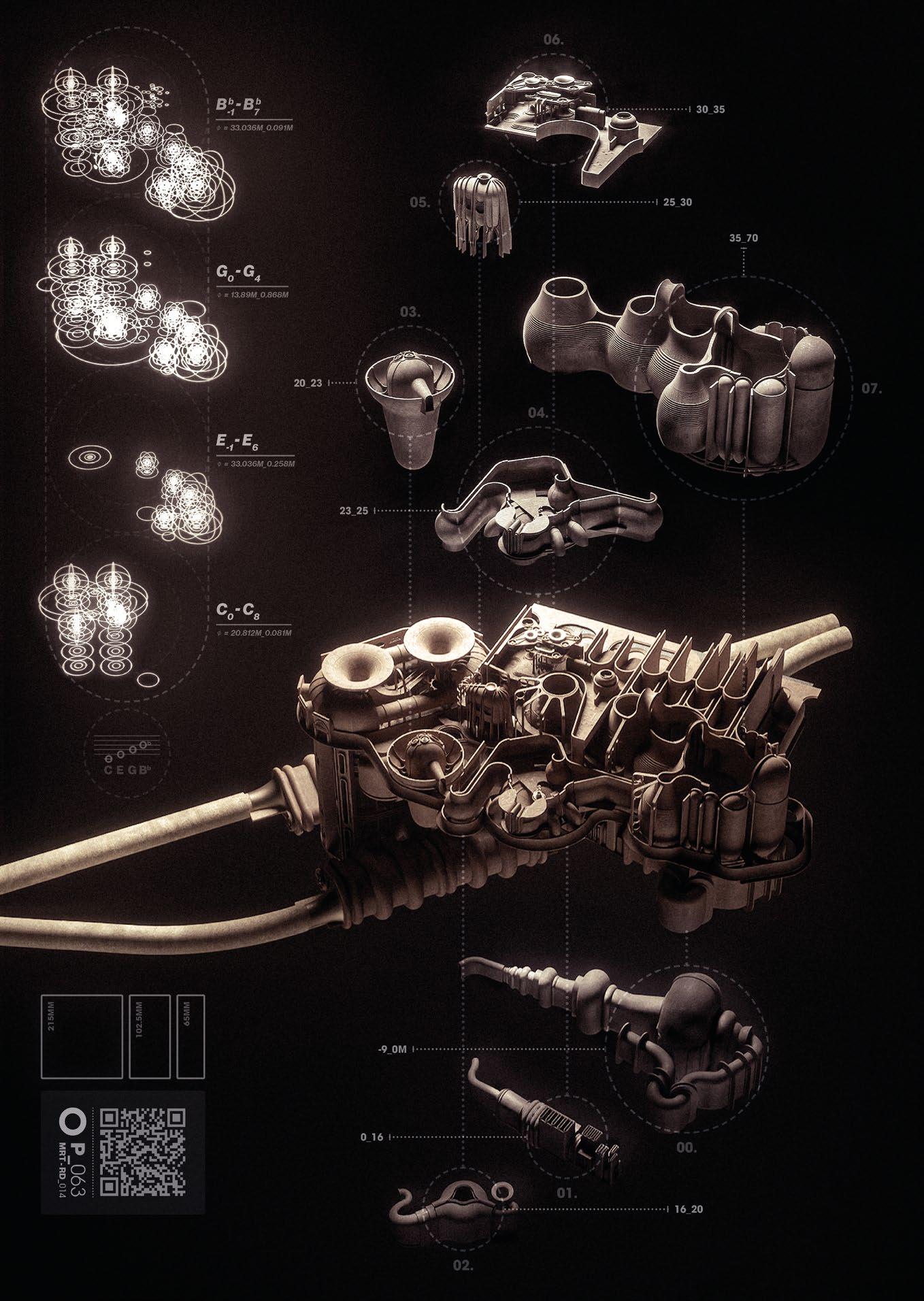

Chak Ming Anthony Tai, Y5 ‘Kowloon Reimagined: Bridging Hong Kong’s Past and Future’. This research project explores the preservation of Hong Kong’s identity through the sustainable redevelopment and regeneration of 1950s tenement buildings. The city has faced a loss of identity due to increasingly largescale redevelopment and gentrification in local areas. These practices, accompanied by the constant demolition and profit-driven culture, have hindered the development of a distinct architectural identity for Hong Kong. The investigated district of Kowloon City was a vibrant neighbourhood where multicultural communities gathered. Currently, the area faces the imminent displacement of its ageing community to make way for large-scale housing developments. The project offers an alternative vision that prioritises local communities over corporate profits and develops a typology that conserves Hong Kong’s culture and identity through adaptive reuse. By exploring strategies that establish a symbiotic relationship with the existing fabric, this research revives materials associated with local traditions and history. Notably, timber emerges as a forgotten material with the potential to bridge Hong Kong’s future architectural identity with its pre-colonial past. By exploring new technologies in timber, this project ultimately develops a range of regenerative strategies across various scales. 24.3–24.6 Loukis Menelaou, Y5 ‘The Future Is in the Past’. The Palmscape Hotel has everything to ensure the most relaxing of holidays: seaside views, an infinity pool, a meze restaurant and direct access to the beach. Or so it seems... ‘The Future Is in the Past’ is an allegorical exploration of narrative-driven architecture, virtual world-building and the reinterpretation of history to shape our future. The narrative is led by the oral stories of displaced Cypriot people who in July of 1974 were forced to move away from their hometown and can now only access it through their minds and memories. The architectural intention manifests itself as a resort, located in the ghost town of Varosha in Cyprus. The design and materiality of the spaces are informed by the metaphors they carry and the actors in Cypriot history they represent. As an allegory of the displaced person’s mind, the Palmscape Hotel exists as a projection, haunted by the trauma of war. It serves as a reminder that history is a construction, urging the audience to embrace alternative readings and break away from a linear understanding of the past to shape a progressive future. 24.7–24.10 Matthew Semião Carmo Simpson, Y5 ‘The Devil You Don’t’. Drawing inspiration from Bergsonian theories of time and memory, the proposal examines the relationship between architecture, music and memory through the lens of dementia. Parasitising the infrastructure of the abandoned York Road tube station, the project creates an architectural promenade. The programme combines and spatialises the premises of patient-specific music playlists and sensory gardens, deploying virtual space to stimulate the senses and evoke specific memories of a fictional protagonist’s life. Brick, known for its nostalgic connection to British architectural heritage, was chosen as the primary material. Claybased ornamentation complements the brickwork, bridging tradition and innovation. The proposal introduces a proportional system based on musical notes and harmonies, translating musical form into architecture. The entire scheme’s development, from arrangement to detailing, was governed by this musical process. The interdisciplinary methodology incorporated hand drawing, digital modelling, rendering, film and musical composition. The film deploys music, moving images and architecture to depict the process of mental deterioration. What is being proposed is less the building itself and more a system for generating space – virtual or

otherwise – and a new niche in spatial practice. At the highest level, the proposal serves as a call for the profession to embrace its greatest good and essential purpose – its ability to bridge the disconnected. 24.11–24.14 Joshua Richardson, Y5 ‘Ontario, Archipelago’. 01 July 2067: Toronto, a city of 13 million people, becomes the host city for an international World’s Fair to commemorate and critique its own bicentennial. Five years after the 2067 expo, Toronto has cemented its status as the testbed for subversive and dynamic aquatic architectures. New ways of inhabiting the city emerge to reconcile past misdeeds with a new-found optimism for the future. The project concept is positioned as a housing commune born from this future Canadian expo, whereby aquatic architectures are explored and developed in tandem with a speculative future national identity. Akin to Montreal’s Habitat ‘67, the project addresses the challenges of a rapidly changing world. In response to a growing housing crisis in the Greater Toronto area as well as centuries-long tensions involving indigenous communities, these new homes propose an ‘ethical’ alternative to private landownership across Canadian cities. The ‘House Hippo’ and its associated extensions, accessories and pavilions exist to critique the widespread and popular models of suburban living for future generations while tacitly indulging the habits of an increasingly consumer-driven world. These aquatic architectures, modular both in their construction and symbolism, posit a unique architecture of ‘kit-Canadiana’ that organically multiplies across Canadian coastlines with cult-like influence and exuberance. Altogether, the project remains suspended between context-driven practice and satire to generate a series of regionally and culturally informed, joyfully humorous architectures fitted to re-envision the ‘Great White North’ of tomorrow. 24.15–24.18 Cira Oller Tovar, Y5 ‘ Cosmorama’. This project comprises an innovative research centre and museum dedicated to the study of architecture for endangered landscapes. Its name, derived from the Greek words kosmos meaning ‘world’ and orama meaning ‘scene’, aptly captures the essence and objective of this endeavour. Serving as a focal point for architects and scientists alike, the structure offers a distinct and immersive educational experience that transcends physical limitations. By harnessing state-ofthe-art technologies, it seamlessly unites remote locations within one captivating space. Beyond its capacity to generate and replicate extreme climates, the edifice assumes an instrumental role in disseminating real-time information by reporting on the prevailing conditions of the selected environments. Through the integration of live data feeds, monitoring systems and visual displays, it provides up-to-date climate parameters. This approach underscores the significance of faithfully representing the unspoiled magnificence of landscapes and presenting them within their rightful context, nurturing a profound understanding and appreciation for natural environments while emphasising the imperative of their conservation. In alignment with this ethos, the architectural design incorporates local materials, effectively mirroring the surrounding environment and engendering a harmonious coexistence with the site. The project transcends conventional notions of a museum or research centre, assuming the character of an ever-evolving landscape in its own right.

Penelope Haralambidou,

PG24 is a group of architectural storytellers who employ film, animation, VR/AR and physical modelling techniques to help make sense of the complexity of today’s world. Inspired by philosophy, this year we questioned our relationship with matter.

In Vibrant Matter, political philosopher Jane Bennett theorises a vital materiality that runs through and across human and non-human entities. Furthermore, thinkers such as Graham Harman and Timothy Morton propose an ‘object-oriented ontology’ that perceives material things as alive and multi-scaled, sentient even. They insist that we are made of, and are surrounded by, a vibrant world of correlated habitats and non-human conscience: a steel column, a hurricane, a cup of tea, a microbe – all belong to a universal material sameness that created us.

The climate emergency is seen as the result of human activity. Solutions often use the same technological thinking that has led to the crisis in the first place. But what if we firstly (and urgently) reconsider our understanding of the world of things? Instead of shaping matter, can we allow matter to shape our sensibility as designers?

We considered these ideas like sculptors obsessing over raw materials or philosophers engaging intellectually with the concept of matter itself. How is time embedded in matter? How do we define value in materials? What about edible matter and architecture’s relationship to food? When does material become waste?

In the process we invented new types of physical and digital hybrid matter, tethering ethereal new behaviours to tangible material. We reflected on how this new hybrid matter can influence not only our manufacturing, design and entertainment industries, but also our everyday, helping to form new local and global communities. To support this material awakening we explored the historical, social and industrial heritage of diverse sites, portraying the stories embedded in the life of their material resources and the communities that these create. In so doing we moved towards an architecture of vibrant matter.

Year 4

Loukis Menelaou, Cira Oller Tovar, Joshua Richardson, Matthew Semião Carmo Simpson, Chak (Anthony) Tai

Year 5

Vitika Agarwal, Jatiphak Boonmun, Kalliopi Bosini, Paris Gazzola, Gabriele Grassi, Holly Harbour, Daniel Johnston, Carlota Nuñez-Barranco Vallejo, Tom Ushakov, David Wood

Technical tutor and consultant: Matthew Lucraft

Thesis supervisors: Camilo Boano, Amica Dall, Oliver Domeisen, Claire McAndrew, Harry Parr, Tania Sengupta, Robin Wilson, Oliver Wilton, Fiona Zisch, Stamatis Zografos

Critics: Laura Allen, Mark Breeze, Rhys Cannon, Barbara-Ann Campbell-Lange, Marjan Colletti, John Cruwys, Claude Dutson, Pedro Gil, Matt Lucraft, Matei Mitrache, Caireen

O’Hagan, George Proud, Javier Ruiz Rodriguez, Mark Smout, Jasper Stevens, Jonathan Tyrrell

24.1 Paris Gazzola, Y5 ‘My Land, Mine Land’. The project is an investigation into the gold-mining towns of Western Australia. It critiques imported colonial knowledge and imagines a new future for the settlement of Leonora. The settlement is composed of an archipelago of residential islands on the surface that extend into social, commercial and industrial spaces underground. A new kind of desert living is proposed that sits in contrast to the resource-hungry models of the recent past – one based on local resources and knowledge, remediation and the coexistence of different societies. The film explores this interconnected underground realm as a cinematic love letter playing backwards – a hopeful, resilient and optimistic future for a once-scorched Earth.

24.2 Kalliopi Bosini, Y5 ‘Mani Stone Kneaded’. The Greek peninsula of Mani is facing increasingly difficult environmental and social challenges as younger generations move to bigger cities. This internal migration is leading to the gradual abandonment of the region, resulting in the loss of equilibrium between heritage, identity and socio-economic growth. The new settlement in the village of Kardamyli traces the timeless reciprocal relationship between the land, extracted materials and the shaped architecture. A rebirth of the families’ domestic and labour needs is enabled through the exclusive production of olive oil and soap. A new socially, economically and environmentally sustainable Maniotian vernacular is imagined, matching the village’s origins and its true historic identity.

24.3–24.5 Carlota Nuñez-Barranco Vallejo, Y5 ‘Queens of the Desert Age’. Located in southern Spain at a point in the near future, a female-led settlement survives in an incredibly hostile environment. Three primary technological powers (wind, solar and organic matter) are harnessed and sit alongside residential dwellings. Research into the science-fiction genre generated a positive future vision, where climate change is a force for active development. Three mystical ‘queens’ emerge from the desert terrain, each responsible for controlling and channelling their regions’ power, each with an amorphous identity that translates into their respective architectures. Building on utopian visions of agrarian societies, the project comments on the uneven city-centric population distribution in Spanish society.

24.6 Gabriele Grassi, Y5 ‘Wast\ed’. The project explores food production, consumption and waste systems. An unconventional material palette is proposed, fusing traditional building materials with food: an architecture of chocolate, milk, vegetables, plastic, cardboard and wood. A storytelling dining table capable of blurring scales and material conditions, morphs between the fictional and the informational, the real and the virtual. The final film borrows narrative elements of Lewis Carroll’s Alice in Wonderland to tell a contemporary story of consumption and waste. The result is a surreal communal dining hall with a sobering wake-up call to our contemporary state of gluttony.

24.7–24.9 Tom Ushakov, Y5 ‘Gatekeepers of Memory’. The project translates idiosyncratic metaphysical concepts into space and takes the form of pavilions nestled in a speculative landscape. Readings of Pallasmaa, Yates and Plutchik’s ‘Wheel of Emotion’ underpin the layout of this imaginary realm, depicted in a large-scale model/table/mindscape masterplan. Each pavilion is assigned an emotion and a memory which, when combined, create a central edifice –the ‘House of Emotion’. A semi-autobiographical protagonist sets out on a hero’s journey to explore these internal monochromatic landscapes, reflecting on past experience and searching out new forms. Upon his return to reality, he builds the table as a cathartic act, to give an external grounding to his internal world.

24.10 Jatiphak Boonmun, Y5 ‘Performances of Authenticity’. A series of performative architectures reveal the indigenous truths of the Republic of Formosa. Reacting to the fictitious histories presented to the West by George Psalmanazar in the 1740s, the project foregrounds the islanders’ true heritage while also forging new spatial possibilities. Exploring how aboriginal performativity navigates architecture against the backdrop of nuclear waste storage, this filmic architecture exposes and critiques various forms of cadastral land interpretation. The proposal is a quasi-theatre nuclear waste facility that follows a crafted itinerary. It describes a surreal world that sits between performance, theatre and historical storytelling.

24.11–24.13 Holly Harbour, Y5 ‘The Beautiful and the Dammed’. In the mountains of Guatemala, megainfrastructure projects lead to the forced displacement of local Mayan farming communities, with protestations claiming the lives of indigenous activists. The project imagines a new future for a hydroelectric dam that is reclaimed by local people as a site of pilgrimage and a memorial to lives lost. The structure provides a stage for the performance of rituals and festivities whose degree of transience relates to the Mayan calendar, taking inspiration from ancient mythology and the magic realist writings of Miguel Ángel Asturias. The building is shaped by time, water and human activity in a manner that contrasts the traditionally immutable structure of a dam.

24.14 Daniel Johnston, Y5 ‘The Para-Nominal (e)State’. The project explores contemporary ideas of value, which have become eroded as technology has progressed. It asks whether an alternative digital valuation system can create new commodities, typologies and emergent programmes, and how it might alter everyday physical spaces. Responding to London’s housing crisis, a new kind of dwelling is prototyped within the Barking Riverside masterplan, including 19 residential units, a corner shop, bin store and courtyard. Unrestricted by screens, the form and content of the home become warped and twisted. A universal digital overlay is designed within the estate, offering residents the chance to customise their homes and link to the wider community.

24.15–24.17 David Wood, Y5 ‘Capturing the Arctic’. The project describes an expedition, a yearly ritual of capturing, transporting and reconfiguring Arctic ice. Arriving in London, an ice harvester is met by a small flotilla that journeys down the Thames, transforming the ice into a water fountain, an ice rink and an Arctic temple. Mirroring the otherworldliness of remote, extreme landscapes, the film explores the fragility between preservation and loss on a human scale through a part-drawn, part-digital architecture. The ceremonial proposal addresses the overwhelming enormity of shifts that are occurring in the Arctic and the memory of landscapes that are disappearing from sight. 24.18 Vitika Agarwal, Y5 ‘Inhabiting Hybridity’. The project responds to the postcolonial theory of cultural hybridity through a combination of British and Indian culture. The film depicts the migrant experience of being rooted in many places at once. Located at the prime meridian line in Greenwich Park, the proposal obscures the symbolic division between East and West, creating a fertile third space. Stone, a material used in both cultures as a signifier of permanence, is imagined as an amorphous, transcendental material. Through a digital time-based refiguring, it carries the potential to be constantly reshaped by addition and subtraction. The resulting architecture is a hybrid reforming of Britain and India, the past and present, the real and imagined.

Penelope Haralambidou, Michael Tite

PG24 is a group of architectural storytellers employing film, animation, VR and XR and physical modelling techniques to explore architecture’s relationship with time.

This year we continued to address issues of climate change, by reconnecting the body with one of its most basic functions –walking. As the global pandemic upended our lives, we used walking as a primary method of engaging with and reclaiming the city and landscape.

Wanderlust has long been the source of inspiration of many writers and philosophers: Friedrich Nietzsche, Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Virginia Woolf, W.G. Sebald and Rebecca Solnit, amongst others. But, beyond poetry, walking is also linked to abstract mathematical thought, intrinsically related with gauging distance – by measuring units based on the size of the human (male) foot – and the origin of arithmetic calculation itself. Recently, walking itself has become intensely quantified, in number of steps, as an indicator of wellbeing.

We asked, how does wanderlust inform architectural design but also film? Architecture is not experienced as a static contemplation from a single point of view but as a cinematic journey that unfolds in time. A well-designed amble, e.g. the Guggenheim Museum in New York, or the bridging of an impossible passage, e.g. Tintagel Castle Bridge in Cornwall, can be the sole purpose of architecture, which can fulfill dreams of walking on water, e.g. Christo and Jean-Claude’s Floating Piers (2016), or walking on air, e.g. Tomas Saraceno’s On Space Time Foam (2012). Architecture itself can be taken out for a walk. In traditional Japanese festivals, Mikoshi shrines are transported within a district, activating collective space. Archigram’s influential Walking City (c. 1960) can be seen in modern fables such as Howl’s Moving Castle (2004) and Mortal Engines (2018). Furthermore, the representation of walking in the built environment led to inventions such as the dolly system and the Steadicam, which were key to the development of cinema. Advancements in immersive film, VR and XR are allowing this to evolve further; we can now construct a digital spatial overlay around the moving body that can be inhabited in real time.

Between wandering, marching and rambling we questioned issues of mobility, age, gender, race and disability, and studied architecture through the romantic exploratory hike, the habitual daily commute, the purposeful personal quest, the meandering flânerie, the protest, the adventurous expedition and the dedicated pilgrimage.

All of our projects built a new and dynamic design vocabulary, proposing new ecological modes of occupation that can foresee and withstand the needs of our dramatically changing world.

Year 4

Vitika Agarwal, Jatiphak Boonmun, Kalliopi Bosini, Paris Gazzola, Gabriele Grassi, Holly Harbour, Carlota Nuñez-Barranco Vallejo, Tom Ushakov

Year 5

Camille Dunlop, Viktoria Fenyes, Alexander Fox, Maxim Goldau, Yee (Enoch) Liang, Elissavet Manou, Lingyun Qian, Issui Shioura, Matthew Taylor

Thank you to our design realisation tutor Kairo Baden-Powell

Thank you to our consultants: Krina Christopoulou, John Cruwys, Matt Lucraft, Sonia Magdziarz, Jerome Ng, Kevin Pollard, George Proud

Thesis supervisors: Edward Denison, Stephen Gage, Elise Hunchuck, Richard Martin, Niall McLaughlin, Guang Yu Ren, Oliver Wilton

Thank you to our critics: Kairo Baden-Powell, Nat Chard, Krina Christopoulou, John Cruwys, Kate Davies, Pedro Gil-Quintero, Jessica In, Suzanne Isa, Chee-Kit Lai, Stefan Lengen, Matt Lucraft, Keiichi Matsuda, Kevin Pollard, Sophia Psarra, Nick Shackleton, Sayan Skandarajah, Jasper Stevens, Jerry Tate, Manuel Toledo, Stefania Tsigkouni, Tim Waterman, Fiona Zisch

24.1 Yee (Enoch) Liang, Y5 ‘A New New Town’. The allegorical film narrates Hong Kong’s collective consciousness through the city’s New Town Plaza mall. The film follows a boy who enters a surreal parallel dimension of New Town Plaza and wanders through its three spaces. These spaces explore remembering the past, savouring the present and building towards the future. The three spaces act as architectural characters that spatially guide the boy to rediscover his lost childhood and innocence, as a kind of coming-of-age journey in reverse. Allegorically, the boy’s journey represents Hong Konger’s rediscovery of their love towards the city and their perishing dream to preserve an expiring identity and reclaim a right to the city. Universally, it is a story that encourages one to break free from worldly social expectations and forge a future according to your beliefs.

24.2 Lingyun Qian, Y5 ‘Hundred Year Forest Wall’. Addressing China’s commitment to be carbon neutral by 2060, the project is a radical proposal for Beijing –a slow transformation of the old, now lost, city wall site, from the current ring road into a vibrant ‘forest wall’. Conceived as an enormous piece of ecological infrastructure, the proposal reorders the city over a long time period, to send a message of how seriously China takes the environmental crisis. The project’s main theme is creating nature through human intervention within a multi-scale, cross-generational planning framework. Adaptable, mobile and elevated structures are designed to allow the forest and the road to morph, and to form a ceremonial architecture that resembles the old gates and city wall. As we stand at the precipice of environmental failure, the project is a call-to-arms that levers political power and the will of the collective, for the benefit of future generations.

24.3–24.5 Issui Shioura, Y5 ‘Ephemeral Preservation’. The film depicts the world of Sampo, a real-life mobile living unit collective that explores a method for disaster preparation in Japan. The project introduces a series of interconnected interventions that operate on a variety of scales: from the ‘Tact’ mobile expandable kit to the ‘MoC’ mobile cell, and the kura (storehouse) to the mikoshi (portable shrine), each one resists the idea of fixity, drawing on the idea of the void space and historic Japanese architectural modes. Influenced by slacker culture and Mike Figgis’ Timecode (2000), the film is realised as a lo-fi, countercultural rallying cry, where the collective acts of making, gathering, building, remembering (and partying) try to flow with the natural world, rather than create resistive structures. The film is part documentary, part music video; a freestyle rap drives the form of the film. It takes an optimistic attitude and approach to community, rather than built hardware, and offers a new kind of anticipatory, participatory, free-flowing architecture.

24.6 Matthew Taylor, Y5 ‘Bathhouse of Spiritual Purity’. Located in and around the Hie Shrine in the Chiyodo ward of Tokyo, the bathhouse is conceived as a bridge between the real and the divine – an ecological realm where time and gravity play to different rules. Influenced through a personal affiliation with Japan and Shintoism, the project seeks out a new eco-animistic inhabitation for the 21st century and beyond. The design lies between architecture and mythical storytelling, utilising the boundless potentials of animistic values to form an alternative architecture of co-existence. The project gives partial design control to procedural software, conceived as ‘digital spirits’ that guide us on a sacred design journey. From the animations of Studio Ghibli to the paintings of Hieronymus Bosch, and decay simulations to Kami iconography, the final film promotes messages of environmentalism and animistic co-existence.

24.7–24.9 Maxim Goldau, Y5 ‘Matryoshka Tempelhof’. By applying concepts of ‘Shearing Layers’ and ‘Support & Infills’ this housing project inhabits the hangars of the former Tempelhof Airport in Berlin, creating the necessary shelter for a participatory architecture. The project examines how better quality, low-tech, inclusive environments might benefit us all. By questioning the humble functions and elements in our homes, it explores to what extent services and furniture can take on architectural roles by activating a mobile form of construction. The design is realised through a series of inventive installation-like objects that are gradually adapted and changed until they become occupiable interiors. The film gives voice to the disembodied view of the articulated service infrastructure, which together with the occupant become collaborators in a reusable and adaptive architecture.

24.10 Alexander Fox, Y5 ‘Harbouring the Exoskeleton’. This science fiction allegory calls for the preservation of biodiversity, while challenging human interference. Learning from insect life cycles, the architecture takes three forms. In the first, a land train of experimental laboratories, resembling larva or a caterpillar, roams across terrains before decoupling and expanding into inflated biomes, similar to pupa, creating an idyllic habitat, safe from predators, for the reproduction of insects and providing opportunity for scientists to observe. Secondly, the building’s AI system, HIVE (Holistic Insect Vehicular Experiment), controls the architecture to create monolithic structures that house insects, while also tethering the inflatables in place. In the final phase, the building goes through a process of ecdysis – the shedding of old skin – and rebirth. The building rejects the human operators it houses and becomes sentient; a catalyst for environmental regeneration.

24.11–24.14 Camille Dunlop, Y5 ‘Arboreal’. The project operates at the intersection of body, forest and city. ‘Arboreal’ has two sites: the dance is digitally recorded in the Swedish Tyresta National Park forest and is then translated into a dedicated dance hall in Stockholm. The body-in-motion conducts an architectural act between the wilderness and the city, and the choreography becomes a constituent part of a performing architecture. The building also performs through an adaptable, dynamic and ever-shifting system controlled by the performers. Sited in the centre of the city, tree-like columns host swaying translucent fabrics that blend the building into the urban environment. Motion-capture technology is a key part of the research methodology and the programme. While mobility entangles all living beings within the Anthropocene, digital measures of movement create architectural dualities that challenge humancentric space.

24.15 Elissavet Manou, Y5 ‘Not Set in Stone’. The project imagines the establishment of a multi-generational settlement on the windy Greek island of Tinos. ‘Not Set in Stone’ explores the concept of a ‘palindromic’ construction process that results in a dual green marble architecture. One is a positive, additive construction that relates to the intimate and humdrum everyday life through the creation of a notional settlement, the other is a negative, subtractive carving-out of a rock temple in the quarry that reflects the ‘sublime’ essence of Tinos. The dialogue between the two programmes and sites explores an alternative way of living – one that harnesses the wind, and questions the nuclear family typology, the traditional role of women and ideas of the sublime. Exploring ideas of longevity, handcraft, technological advancements and the Tinian vernacular, the scheme creates a tension between the everyday and the extraordinary.

Penelope Haralambidou, Michael Tite

PG24 employs film, animation, virtual and augmented reality, and physical modelling techniques to nurture free thinking and architectural storytelling, and to explore and expand architecture’s relationship with time. As we emerge from a recent ice age, Earth’s atmosphere continues to heat up. Scientists protest that mankind is directly responsible, but the word of climate change is still not accepted as gospel. We must reduce, give up, fast and exercise self-control. We are guilty and our guilt makes us fallible. In the grey areas of doubt, a new kind of faith has emerged, unchallenged by fanatics and dismissed by heretics. Has climate change become a new religion?

While the male-dominated, white, proto-religious debates swell, global inequality grows and the planet pays the price. Within this febrile territory, what is the role and responsibility of architecture? The built environment’s 40% contribution to our total carbon footprint is eye-watering, but it also presents a huge design opportunity. Can the looming catastrophe of climate change be switched into a positive creative force? Can technology really save us? Can we design guilt-free?

As a direct response to the Architecture Education Declares open letter, this year we engaged with a deep study of the cultural and geo-scientific parameters of climate change. We questioned identity: How do we situate ourselves when we design and for whose benefit? Can we think from a ‘post-human’ position, seeking radical new approaches that are more effective and inclusive, outside the guilty conscience of the ‘humanity’ that created the problem?

We redefined matter: Can we transform the current linear thinking of take/make/consume/discard, into a circular ecology of materials and building parts? Often in architecture we design perfect births, but this year we used long-term thinking to design perfect deaths and planned ahead for the end of life of buildings. We employed technology: While the atmosphere deteriorates, another digital atmosphere, a digital twin of the Earth, has emerged, able to computationally monitor, predict and address future change. How can we future-proof sustainable buildings by designing them in parallel to their intelligent and responsive digital twins?

We visited the swamps, cities and low-lying terrains of Florida, to explore a region that has both exacerbated the problems of, and is catastrophically threatened by, climate change. Here, retirement communities and ghettos coalesce where the flooded marshlands swell and huge metropolitan complexes sprawl; terrains of space exploration and luxury golf courses meet hurricane warnings, digital magic, fried food and voodoo. We explored this conflicted identity of culprit, victim and saviour to form our own design manifestos and propose new parables of evolving ecologies.

Year 4

Camille Dunlop, Viktoria Fenyes, Alexander Fox, Maxim Goldau, Yee (Enoch) Liang, Elissavet Manou, Lingyun Qian, Matthew Taylor, David Wood

Year 5

Krina Christopoulou, Lucca Ferrarese, Hanna Idziak, Maria Konstantopoulou, Afrodite Moustroufi, George Proud, James White

Thanks to our technical tutor Kairo Baden-Powell

Thank you to our thesis supervisors Alessandro Ayuso, Ben Campkin, Murray Fraser, Stephen Gage, Tasos Varoudis, Simon Withers, Stamatis Zografos

Thanks to our critics Ollie Alsop, Nat Chard, Kate Davies, Egmontas Geras, Alex Holloway, Jessica In, Greg Kythreotis, Sonia Magdziarz, Tim Norman, Nick Shackleton, Sayan Skandarajah, Jasper Stevens, Tasos Varoudis, Izabela Wieczorek, Simon Withers, Fiona Zisch

24.1 Maria Konstantopoulou, Y5 ‘The Spirit of the Liquid Marshes’. Sited in Bayou Tortillon, a vast swamp region in Southern Louisiana, the project imagines a partsubmerged world, inhabited by low-tech hydroengineered infrastructures and peculiar humanlike scavengers called ‘Lossans’. In response to the mythic power of this threatened landscape and inspired by Donna Harraway’s ‘Chthulucene’, JG Ballard’s ‘Drowned World’ and the writings of Jorge Luis Borges, Mary orchestrates an ambitious magical realist intervention, part poem, part architecture. A pair of ambiguous creatures emerge as cavernous inhabitable structures that relate to ancient mythological orders and straddle our middle world and the realm of the spirits. They are intended as pieces of infrastructure operating outside of human time perception, capable of healing, yet with unpredictable and potentially destructive behaviours. Slippery interior worlds of mysterious organ-like forms give way to large animalistic exteriors with plasto-reptilian skins that finally merge into the swamp itself.

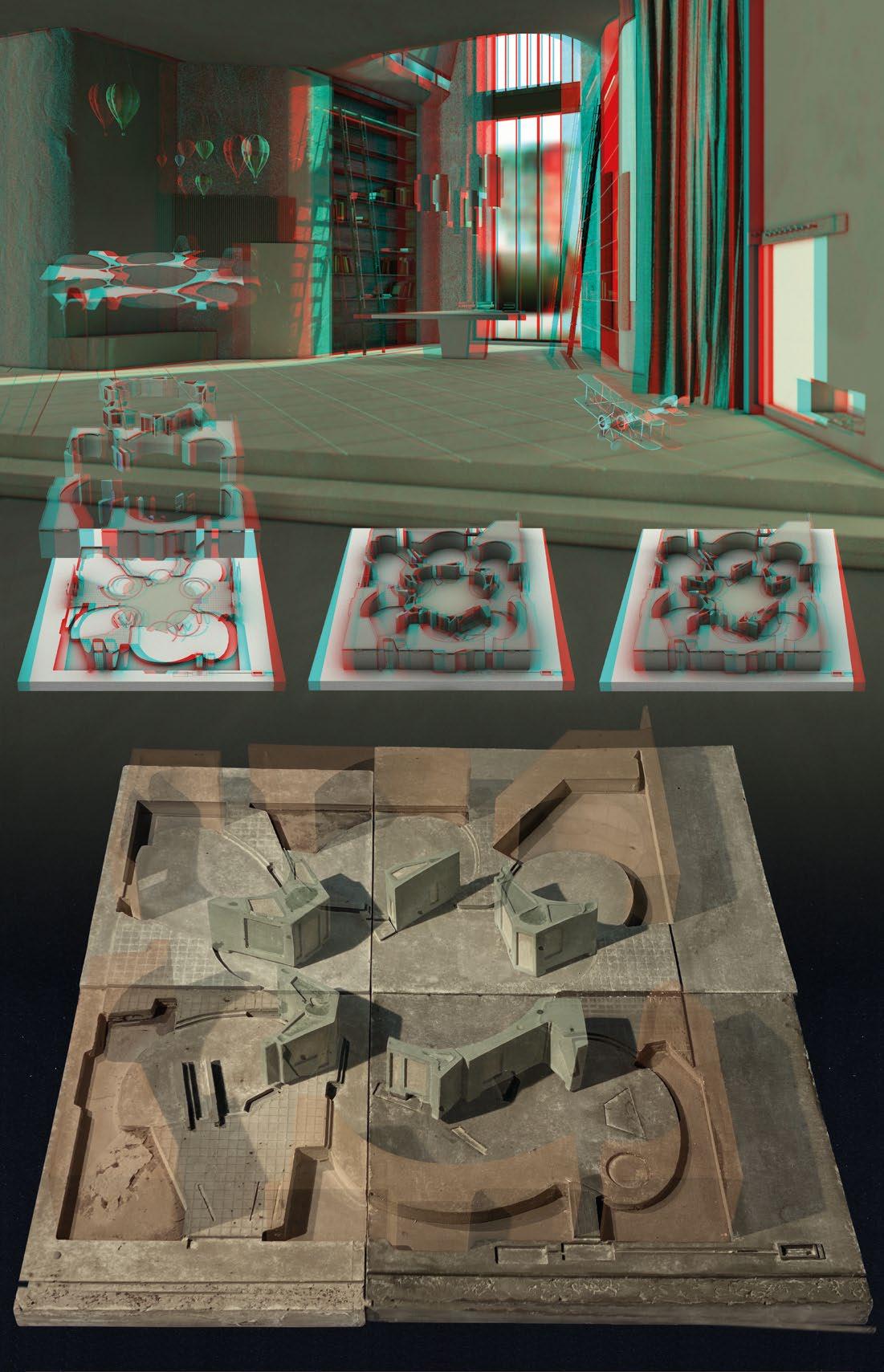

24.2 Afrodite Moustroufi, Y5 ‘Projections on Learning’. Through a series of playful and immersive investigations with projections, this project developed a vocabulary of tools that allow an occupancy of illusory stereoscopic space as a working extension to the physical space that frames it. Using stereoscopy both as a design method and as programmatic catalyst, the proposal for an experimental school in Silvertown is capable of recording and then three-dimensionally projecting parts of the building onto itself, allowing the school to expand virtually. The three-dimensional projective design method is coupled with precise physical modelling in coloured plaster inspired by Isamu Noguchi’s landscape models. As a ‘machine for learning’ that exists in both physical and projected form the school occupies a realm of extra dimensions, where moving elements rotate and redeploy to form different teaching environments. The film becomes a promotional video for the school, including first-person experiences and the voices of the children, conveying a childlike sense of wonder that challenges our embedded ideas of space and time.

24.3–24.7 Hanna Idziak, Y5 ‘Garden of (Im)permanence’. This project explores the past of Gdansk shipyard, as a tool for understanding the wider politics and history of Poland and imagines a redevelopment of the postindustrial site into a women’s centre. The architectural film acts as a protest against the patriarchal attitudes of the current conservative government, which uses architectural preservation and demolition to distort history. Drawing from UNESCO’s definitions of tangible and intangible heritage; the notion of Anti-Monument by architects Zofia and Oscar Hansen; and the undulating brickwork techniques of Eladio Dieste, the project commemorates the forgotten histories of the women working on the shipyard, which the heroine describes as a ‘mother’. Architecture becomes a collective act, where the women disassemble the brick warehouse onsite to create a new form, which is slowly taken over by nature, becoming a time-conscious monument to the past, present and future. 24.8–24.11 Lucca Ferrarese, Y5 ‘Vauxhall Pleasure Palace’. Set in Vauxhall in the near future, in a postCovid-19 world, where the virus has been completely eradicated and local lockdowns have ended, this film sees two lovers reunited for the first time since their government-imposed hiatus. The project investigates the links between social technology, gender identity, performance, public space and the state. The work extrapolates the consequences of the pandemic into the future, but also tunes into the wider undercurrents that are seeing disenfranchised sections of society seek out new modes of occupancy within the city. Ideas of

reclaiming public space through reclaiming the body and fusing fashion with architecture are imagined within a reinvigorated nocturnal realm for the city. The project draws on the rebellious art/performance/fashion practices of Lee Bowery, Oscar Schlemer and Issey Miyake. The carnivalesque neon-lit world, the nervous behaviours of its occupants and the semi-automated glossy movements of the machine-building, are depicted with a nudge, a wink and gentle tongue-in-cheek wit. 24.12–24.15

James White, Y5 ‘Guilt-Free Homes’. Guilt-Free Homes explores the increasingly intrusive role of Mega-Cap US technology companies in the domestic realm and speculates on the future commodifying effect they will have on housing. Located in Somers Town, the residential scheme encourages us to accept the experimental intertwining of virtual and physical realms, where we might be free from labour, engaged with local urban identity and where environmental responsibility is offset on our behalf. The work is grounded in a series of observations about our evolving relationship with consumption and technology and ‘feels for the beating pulse’ of what defines living in the 2020s. The project draws on a wide range of historical, theoretical and technical influences, including Harlow’s destroyed heroic modernism, Adrian Forty’s 1986 book Objects of Desire and contemporary object-oriented interior design. The film is an Orwellian ‘cat-and-mouse detective thriller’, immersing us in a disorientating and menacing 360° narrative.

24.16–24.19 George Proud, Y5 ‘The AR-k’. The AR-k is a long-term oral history archive located on the Somerset Levels, which is also composed as the architectural equivalent of a love letter to the author’s homeland. Rooted in the rich mythical history and contemporary local culture of Somerset and Glastonbury the proposal takes on a monastic/sound recording and producing arrangement that imagines an innovative use of augmented reality. Head archaeologist, Dr Fouracres, is our guide in the far future setting of 2442, describing the gradual discovery of a mixed physical/digital ruin. The project considers the material and immaterial aspects of architectural heritage, playing with scale and deep time to depict a warning for the future. Architecture becomes a reliquary, hosting the lost sounds of the past through audio as well as visual augmentation coded in matter. An ode to both the relationship between physical space and its digital extensions, but also to the design process itself, the film is a feat of architectural storytelling.

24.20 Krina Christopoulou, Y3 ‘The Third Space’. The Third Space investigates the evolution of the domestic realm, where 2D ‘point-and-click’ computer interfaces transition into intuitively operated 3D inhabitable digital environments. By designing both the physical home of the future and the virtual spaces it can host, this project speculates on a post-Covid-19 world where houses do not have computers in them, but are computers themselves. The home becomes responsively robotic and rearranges itself to accommodate the resident’s virtual inhabitation, but also becomes a realm for global exploration, entertainment and deep-thought. This haptic installation, where physical anchors tether us to the ‘real world’, acts in tandem with dream-like explorations into what might constitute ‘everyday living’. Architecture’s role in learning, working, socialising and living communally online is redefined and spatial distance collapses, forming new worlds within worlds. With ‘George XP’ as our sassy virtual companion, we dive headlong into an ever-expanding architectural universe, without ever having to open our front door.

Penelope Haralambidou, Michael Tite

In PG24, we employ film, animation, virtual reality (VR), augmented reality (AR) and physical modelling techniques to explore architecture’s relationship with time. We nurture free thinkers and storytellers who find inspiration in both film and architecture, studying their intertwined histories and seeking the myriad possibilities arising from their merger.

This year, we turned our attention to the fast-changing nature of architectural drawing. Time charges and enlivens space in drawing. It can reveal the process of assembly, predict responses to weather, calculate future patterns of occupation, connect with the past, imagine the future, unfold a narrative, build atmosphere, engage with sound and light, and relink architectural composition with the senses. Filmic drawings lead to empathetic design. At the same time, ubiquitous computer-aided design (CAD), building information modelling (BIM) and artificial intelligence (AI) have the potential to eradicate the need for drawing entirely. If a building can draw itself, what is the role of the architect? Has the digital mechanised the hand? Can we draw 1:1 and inhabit the drawing whilst it is being drawn? Can we close the loop between drawing, manufacture and inhabitation by allowing instantaneous feedback between the three? Can digitally disseminated drawings democratise architecture, expand the impact and reach of architectural ideas, and bring communities together? According to Rem Koolhaas, 50% of the global population now lives in cities and, as a result, we tend to ignore 98% of land: the countryside. Economically and socially overlooked, the rural is the realm of the most rapid and radical change, and the testbed for the future of the world. A colossal ‘back-of-house’ that feeds, maintains and entertains ever-growing cities, the countryside has historically been the site of utopic visions, centres for study and contemplation, labs for testing new building paradigms, spiritual retreats, sanctuaries for healing and art collections. It can be dreamed up as paradise and idyll, but also demonised as the location of existential horror.

Inspired by our visit to Niall Hobhouse’s remarkable Drawing Matter archive at Shatwell Farm in Somerset and our road trip through Europe, we cast off our urban predilections and ventured into the rural. Beyond farmed land, we looked for sites in the wilderness – forests, mountains, oceans and even the atmosphere –and used digital drawing and cutting-edge technologies to narrate new architectural prototypes that change the way we conceive and inhabit space.

Year 4

Krina Christopoulou, Lucca Ferrarese, Alex Haines, Hanna Idziak, Maria Konstantopoulou, Maria Afrodite Moustroufi, George Proud, James White

Year 5

Alexander Ball, Flavian Berar, Uday Berry, Lee Kelemen, Pascal Loschetter, Jerome (Xin) Ng, Sylwia Poltorak, Marie Walker-Smith

Special thanks to Keiichi Matsuda. Thank you also to our Design Realisation tutor Matt Lucraft; our consultants Kevin Pollard, Ali Shaw and Ben Sheterline; workshop/ seminar leaders Finbar Fallon and Jack Holme; and Niall Hobhouse and Susie Dowding at Drawing Matter, Somerset

Thank you to our critics: Laura Allen, Ollie Alsop, Barbara-Ann CampbellLange, Rhys Cannon, Nat Chard, Nigel Coates, John Cruwys, Elizabeth Dow, Ava Fatah gen. Schieck, Maria Fedorchenko, Maria Fulford, Pedro Gil, Kate Goodwin, Stefania Gradinariu, Kevin Green, Sean Griffiths, Colin Herperger, Niall Hobhouse, Jack Holmes, Jessica In, Chee-Kit Lai, Matt Lucraft, Abel Maciel, Thomas Millar, Matei Mitrache, Caireen O’Hagan Houx, Sophia Psarra, Nick Shackleton, Jasper Stevens, Stefania Tsigkouni, Nimrod Vardi, Kevin Walker, Tim Waterman, Simon Withers

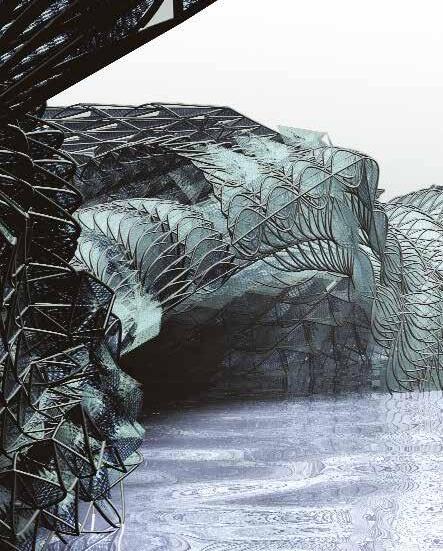

24.1 Flavian Berar, Y5 ‘Engines of Creation’. In response to existential threats posed by climate change, artificial intelligence and nanotechnology, ‘Engines of Creation’ explores potential new directions that architecture might take, reacting to and against these potent forces. Located in the heart of Europe, within the neutral, yet hostile, territories of the Swiss Alps, the project begins as an alternative Future of Humanity Institute. Conceived as a mythical research laboratory, where ‘Citizens of Nowhere’ gather to shape our Post-Anthropocentric interplanetary future, the building slowly evolves over a long time period in response. A radical landscape of the sublime, this is a visionary regenerative architecture born out of the merger of art, nature and technology.

24.2 Lee Chew Kelemen, Y5 ‘Proxima Estacion: Via (De)Colonial’. Over the last four decades, the Argentinean railway network has slowly fallen into ruin, leaving many rural communities disconnected and struggling for survival. The crumbling town of Mechita – once home to the largest railway workshop in South America – finds itself hollowed out: its citizens, having long since migrated away to urban areas, have left behind the carcasses of thousands of disused trains. A new ‘De-Colonial Line’ emerges from these ashes; a line that will awaken the spirit of the trains once more. Wearing ‘architectural masks’ given to them by the remaining community, the train carriages house new mutating programmes such as micro-banks, Pulperia, football pitches, protest walls and carnival floats. The trains act nomadically, not knowing when they will leave or return, bringing with them a dynamic exchange of civil disobedience as well as cultural, economic and social events according to the needs of the rural population.

24.3–24.5 Pascal Loschetter, Y5 ‘The Unnatural History Museum’. Emerging from a coastal landfill site on the Thames Estuary and telling the story of a landscape of waste, ‘The Unnatural History Museum’ is a new kind of building that is part-museum, part-monument, part-land art. The museum exhibits markers of our time which contribute to the geology of the future. The architecture itself acts as a monument to the current age of excess by displaying petrified ‘memories’ of landfill objects within the building’s skin. The process carried out to create the building – whereby material is excavated and transformed into plasma rock – remediates the entire landscape, recreating a habitat of salt marshes for the local fauna and flora. Gradually constructed as a remnant of the transformed landscape, the building draws value from the materials found on the site, whilst mitigating against the environmental damage associated with the archaic processing of landfill.

24.6 Marie Walker-Smith, Y5 ‘The Last Forest: Rothiemurchus 2098’. The year is 2098. The Rothiemurchus Project in the Scottish Cairngorms stands as the ‘Last Forest’, the final remnant of a doomed UN experiment to protect global biodiversity. A central ‘ark’ building, designed initially to protect plant life in perpetuity, has been left to ruin. Yet, against the odds and for better or worse, the intelligent robotic infrastructure, designed to maintain the forest, appears to have adapted and grown. As an inquisitive biologist infiltrates the Last Forest, we accompany him to discover how corruption and disorder might be forces for survival. The mysterious world we find there asks us to consider who its architecture is for, how custodianship might shape space and how the idea of ‘nature‘ itself might evolve in time.

24.7–24.9 Alexander Ball, Y5 ‘Dreaming in the Shadows’. Streaming services such as Netflix and Disney+ are not only transforming the way that films are produced and distributed, but are also threatening the film theatre as an urban artefact. Inspired by the horror genre, 1950s visions of domesticity and The Twilight Zone, a strange installation is imagined on the sacred ground of the recently demolished Marble Arch Odeon. Blurring the boundaries between the architectural home and architectural cinema, the film charts the slow disintegration of the central protagonist. Where is his identity centred? In the home or the cinema? Or an uncomfortable strange place belonging to neither?

24.10–24.12 Sylwia Poltorak, Y5 ‘The Independent State of Melanfolly’. What is architecture? How long can it last? Can it help us endure time itself? The answer is definitively, yes it can! The Independent State of Melanfolly is a secretive cultish island state, lying somewhere in the South Pacific. The rebellious insiders, who refer to themselves as ‘lobsters’ have developed a mysterious bio-scientific system to extend their existence through the cryogenic growth of artificial organs. Trees twitch with gossip, walls flow with mysterious red liquid and all is watched over by the mysterious ‘banner girl’. Give in to this wild, noxious, moonlit party-architecture; you cannot escape it.

24.13–24.16 Uday Berry, Y5 ‘The Tower of a Forgotten India’. Exploring the politics, cultural forces and power struggles underlying architectural heritage and conservation in India, this project proposes an extraordinary tower that acts as a living museum, protecting the nation’s threatened and under-valued buildings. Threats come from every direction: religious fundamentalism, rampant modernisation, the culture of collectability and political corruption. In a rapidly developing and ever-changing nation, heritage is seen here as a living part of the city, rather than a site for displaying museum pieces. The tower breathes life back into these forgotten building fragments, reintegrating them into the city’s urban fabric. Firing us into the heart of the sprawling chaos of Delhi, ‘The Tower of a Forgotten India’ is a modern parable spanning decades that seems to suggest that taking control of a city’s past is, in the end, a fool’s paradise.

24.17 Jerome Ng Xin Hao, Y5 ‘Metabolist Regeneration of a Dementia Nation’. Singapore’s Golden Mile Complex is celebrated in many countries as an important icon of 1970’s Metabolist urbanism, yet, in its home city, it faces imminent demolition. More than 80 similar sites have already been destroyed, as part of a progressive nation-building programme. More will follow. This project speculates on an alternative vision for this huge residential block, that not only saves the building, but allows it to absorb physical artefacts from Singapore’s threatened urban infrastructure. It acts as a prototype for an alternative pattern for future development, allowing residents to forge new memories, whilst giving space for the past to breathe. The animated film documents the lives of a series of Golden Mile residents, urging us all to resist the power structures that see our urban memories so readily erased.

Year 4

Alexander Ball, Flavian Berar, Uday Berry, Thomas Cubitt, Lee Kelemen, Pascal Loschetter, Jerome (Xin) Ng, Sylwia Poltorak, Marie Walker-Smith

Year 5

John Cruwys, Tom James, Sonia Magdziarz, Matei Mitrache, Masahiro Nakamura, Rosemary Shaw, Paula Strunden, Stefania Tsigkouni

Special thanks to Keiichi Matsuda, Leap Motion, for digital film, animation and interactive media teaching

Workshops/seminars: Grand Gee, Jack Holmes, Shedworks, Jasper Stevens

Thank you to our consultants: Kevin Pollard, Ali Shaw, Ben Sheterline

Thank you to Carl-Dag Lige, Sille Pihlak and Harri Taskinen for their help during our fieldtrip to Estonia and Finland.

Thank you to our critics: Ollie Alsop, Anna Ulrikke Andersen, Ruth Bernatek, Tom Brown, Nat Chard, Nigel Coates, James Craig, Elizabeth Dow, Grant Gee, Christophe Gérard, Pedro Gil, Kevin Green, Gonzalo Herrero Delicado, Joanna Karatzas, Chee-Kit Lai, Ifigeneia Liangi, Matt Lucraft, Martyna Marciniak, Tomas Millar, Phuong-Trâm Nguyen, Caireen O’Hagan Houx, Luke Pearson, Sille Pihlak, Fleur Praetorius , Sophia Psarra, Nick Shackleton, Sayan

Skandarajah, Amalia

Skoufoglou, Jasper Stevens, Kevin Walker, Fiona Zisch

Unit 24 is a group of architectural storytellers employing design, film, animation, drawing, virtual and augmented reality and physical modelling to explore architecture’s relationship with time. We nurture free thinkers, who are prepared to explore novel ideas and techniques. We find inspiration in the dialogue between film and architecture, study their intertwined histories and seek the magical possibilities arising from their merger.

This year we turned our attention to the evolving notion of craft. A renewed attention to craft – and its related values of authenticity, engagement with materials, personalisation, skill, care, time and provenance – has recently emerged. The popularity of Etsy, Minecraft, BrewDog and The Great British Bake-Off attest to craft’s resurrection in unexpected forms that respond to, and harness, the post-digital economy.

Today, when new digital technologies are rendering the nineteenthcentury dichotomy between the hand and the machine obsolete, where does craft lie in architecture and film? How does it manifest itself in brick, stone and celluloid, or in drawing, editing and cinematography?

To find out, in November we headed north on a road trip to the lands that shaped the work of two modern master craftsmen: an architect and a filmmaker. In Helsinki, we visited celebrated buildings by Finnish architect Alvar Aalto. He pioneered a design ideology rooted in craft, nature and technology and forged a productive relationship with industry, which allowed the hand of the studio to remain close to built artefacts: from vases to staircases and chairs to roofscapes. We then took the boat across the Gulf of Finland to Tallinn, the city whose fringes acted as the backdrop for the film Stalker by Russian director Andrei Tarkovsky. Obsessed with craft, Tarkovsky saw film as a poetic act of making: a sculpting in time. One of the best-preserved, UNESCO-listed, medieval cities, Tallinn is also dubbed ‘the Silicon Valley of Europe’, with the highest number of start-ups, a digital economy driven by blockchain and e-residency.

Our projects searched for a redefinition of craft beyond digital form-finding, using narrative and storytelling to address place, memory and performance. We defined hybrid practices between architecture and filmmaking that also blur the boundaries between design and experience. And we asked: What is the relationship between materiality and craft? Or craft and ethics? Is craft still grounded in local, individual skill, or can it be dispersed between many in the cloud, crowd-sourced and spread globally? And how can we overcome ‘the handmade versus the machine’ in an era when the human hand has been softly mechanised by immersive digital technologies?

Year 4 students proposed time-crafted architectures within the modern economies of Finland and Estonia and Year 5 students created architectural ‘essay-films’ that sculpt time. A series of specialist workshops with filmmakers, videogame designers, visualisers, Virtual Reality developers, musicians and sound technologists supported our work.

Fig. 24.1 John Cruwys Y5, ‘Festival of Fulfilment’. The project explores how contemporary ideas of work, craft and ritual can shape perceptions of value in the built environment. The tripartite essay film follows the delivery of twin public buildings – a Town Hall and a Festival Hall – as part of an indefinitely prolonged Festival of Fulfilment in the town of Rugeley, Staffordshire. Incorporating the skills and techniques of the post-digital workforce, the festival is ambivalent to form, material, tradition, and scale. It seeks to embed a meaningful practice of building for the sake of building, to create a lasting civic presence and ultimately appease the mind and soul. Fig. 24.2 Matei Mitrache Y5, ‘Edenic Polyphony’.

The project brings together historical research into Dante’s Divina Commedia with acoustic design to form a new kind of

operatic landscape within a charged site in Tartu, Estonia. Preserving the imposing presence of the ruined manor, yet revitalising the site, it proposes an episodic journey through a sonic terrain. The film explores the architecture of hell, purgatory and paradise through the eyes of its subjective protagonist and its omniscient narrator. Fig. 24.3 Masahiro Nakamura Y5, ‘Imaginarium of a Legacy’. The film is an architectural polemic exploring the implications of the physical annexing of Hong Kong into a new Chinese-funded sovereign city state. It follows the journey of a young protagonist through ‘The Emancipated State of Hong Kong’ an island suspended above the ocean, as a perfect utopian version of the original city. Inspired by the role of identity in Anime, a series of dream-sequences help re-awaken the subdued democratic spirit.

Figs. 24.4 – 24.5 Tom James Y5, ‘(Re)Creation: Constructing the Zone’. Influenced by the central thematic device of Andrey Tarkovsky’s Stalker (1979), the Zone is a proposal for a sculpture park containing recovered digital fragments of Manchester’s lost built heritage. Captured from film, using slit-scanning and photogrammetry techniques, the fragments are overlaid into the parklands of Nutsford Vale in East Manchester. The project explores themes of preservation and memorialisation and provides a platform of resistance for a city undergoing transformative waves of speculative development. Fig. 24.6 Stefania Tsigkouni Y5, ‘Silk Tales’. An architectural fable studies the complex dynamics of Athens, focusing on the interweaving lives of a community within the working-class neighbourhood of Metaxourgeio. The project

plays with cyclical time as a way of drawing out relationships between humans and the forgotten natural world within the city. Magical elements nurture the themes of displacement, labour, craftsmanship and explore mobility within the social ecology. Reality acts as a trickster and consequently, causality as an illusion. The buildings become characters in themselves, engrained with the city’s mythology, and its ongoing history. Figs. 24.7 – 24.8 Rose Shaw Y5, ‘Ebbsfleet Town Square’. If urban space is played rather than planned can it give rise to more creative uses? Located at the epicentre of a planned Garden City at Ebbsfleet, the proposal is a speculative framework for public space ownership, re-inventing the town square for post-Brexit Britain. An illuminated game-board is placed at the centre of the process, which links to a full-scale

immersive projection environment. Within a structured system of rules, the kit of parts can be re-configured by different stakeholder groups. A world where lateral thinking, negotiation skills and even a little gamesmanship are the highest forms of influence. Fig. 24.9 Paula Strunden Y5, ‘Micro-Utopia’. The project proposes an immersive and interactive version of the home, where space is born from the finely-tuned sensorial interplay between the body and the physical/virtual objects connected to the Internet of Things. A chair invites us to stay with it for a moment; we crawl through a demanding fireplace; our hands are washed in a bowl of digital liquid. Drawing on radical art practice, interiors in historical painting and contemporary product design, Micro-Utopia is the dream of a house that is nothing but the parameters of our perception,

triggered by the metaphorical dimension of the objects we interact with on a daily basis. Fig. 24.10 Sonia Magdziarz Y5, ‘How to Carve a Giant’. Inspired by the mystical Finnish poem ‘Kalevala’ the project proposes an architecture capable of keeping knowledge safe for millennia. Building on the granite boom of the Romantic era, it carves a folk story directly into the solid rock outcrops of the Pasila region in Helsinki over a very long period of time. A mysterious giant emerges sitting under an earthly blanket, protecting the knowledge of Finland and setting in motion the future stories of stone-crafted guardians: the blacksmith, the bear and the fox. This epic folk tale brings together a range of cosmic forces into a fabricated urban topography – from the mineral to the mythical and the mortal to the timeless.

Year 4

John Cruwys, Tom James, Matei Mitrache, Masahiro Nakamura, Rose Shaw, Paula Strunden, Stefania Tsigkouni

Year 5

Sabina Berariu, Thomas Brown, Clare Dallimore, Matthew Lucraft, Martyna Marciniak, Gergana Popova, Nick Shackleton, Jasper Stevens

Special thanks for digital film, animation and interactive media teaching to Keiichi Matsuda

Workshops:

Angeliki Vasileiou, Kevin Pollard, Neutral Digital, Shed-Works, Studio Archetype

Thank you to:

Jack Holmes, Sergio Irigoyen, Rashed Khandker, Greg Kythreotis, Brook Lin, Sam McGill, Dan Scoulding, Ben Sheterline

Thank you to our critics: Ollie Alsop, Anna Ulrikke Andersen, Nat Chard, Patrick Chen, Daniel Cotton, Nico Czyz, Max Dewdney, Stephen Gage, Tamsin Hanke, Colin Herperger, Ifigeneia Liangi, Chris Pierce, Merijn Royaards, Sayan Skandarajah, Henrietta Williams

Unit 24 is a group of architectural storytellers employing film, animation, drawing, VR/AR and physical modelling in pursuit of spatial propositions that harness the potential of time-based media. We nurture freethinkers who investigate ideas and techniques in collaboration with other likeminded experts. We find inspiration in the dialogue between film and architecture and their intertwined histories; film has the power to construct the psyche of a city while architectural ideas are changing the way that film is generated and understood.

This year we turned our attention to the growing frictions between urban bubbles of overabundance and post-urban pockets of debilitating scarcity. We asked whether a cinematic architecture of ‘make-believe’ can address this dichotomy with proposals that marry fact and fiction.

In November, in the immediate aftermath of the US Presidential Election, we explored the contrasting territories of LA and Arizona, tracing a path across the underlying geographic, social and fictional fault lines that separate these neighbouring, yet deeply diverse regions. Since it first swelled out of the Californian desert in the late 1800s, the growth of LA has been inextricably linked to the business of making moving images and storytelling. Conversely, the cinematic landscapes of Arizona have provided the outward gaze for America to reflect upon its history. This sense of emptiness breeds the mythical and surreal, triggering sightings of unexpected objects and the birth of conspiracy theories.