REFRACTED GEOGRAPHIES

ARCHITECTURAL HISTORY MA THE BARTLETT SCHOOL OF ARCHITECTURE, UCL

ARCHITECTURAL HISTORY MA THE BARTLETT SCHOOL OF ARCHITECTURE, UCL

The graphics for this publication are inspired by the theme of the symposium, taking Richard Buckminster Fuller’s Dymaxion Map as the basis. Based on an unfolded icosahedron, the map presents an unfamiliar view of the planet and its

The Bartlett School of Architecture, UCL

22 Gordon Street

London

WC1H 0QB

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, distributed or transmitted in any form or by any means, including photocopying, recording or other electronic or mechanical methods, without the prior written permission of the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical reviews and certain other noncommercial uses permitted by copyright law.

Individual essays © 2024 by their respective authors

Symposium Organisers:

Yanqi Huang, Secretary

Catherine Cull Thomas

Ed Davison

Rodney von Daffer-Jordan

Radhika Jhamaria

Publication & Graphics:

Rodney von Daffer-Jordan, Executive Editor

Ed Davison, Editor

Radhika Jhamaria, Graphics & Website

Pimachok Na Patalung, Graphics

Bashayer Kadhim, Graphics

Symposium Supervisors & Architectural History MA Co-Directors:

Professor Barbara Penner

Dr Robin Wilson

Teaching Staff:

Professor Iain Borden

Professor Ben Campkin

Professor Mario Carpo

Professor Murray Fraser

Dr Sam Grinsell

Professor Jane Rendell

Dr Tania Sengupta

Contributing Staff:

Professor Eva Branscome

Professor Edward Denison

Dr Polly Gould

Ievgeniia Gubkina

Dr Emily Mann

Professor Peg Rawes

Guang Yu Ren

Dr David Roberts

Colin Thom

Dr Azadeh Zaferani

Dr Stamatis Zografos

Course Administrator: Drew Pessoa

With special thanks to:

Dr Deborah Saunt

Dr Sam Grinsell

Professor Peg Rawes

Dr Tania Sengupta

This publication is a collation of papers submitted by the 2023-24 Architectural History MA cohort, published in conjunction with a symposium held on 9 November 2024.

The Keynote Speaker was Dr Deborah Saunt: Deborah is one of the founding directors of DSDHA. She established the Jane Drew Prize in Architecture. She regularly talks and writes on issues of diversity and innovation in the built environment.

11

‘The Esher Report’: Architect-Planner Lionel Brett, 4th Viscount Esher and the Architectural Culture of Conservation in Post-War Britain, 1964-71

Yanqi Huang

The Architecture of Jean-Michel Folon: An Artist’s Contribution to the (Post)modern Architectural Discourse

Inigo Custers

17 Covent Garden is for the People: The Emotional Experience of Covent Garden’s Redevelopment (19711980) and Its Legacy

Elise Enthoven

23 Interspecies Oceanic Colonialism at the Hektor Whaling Station, Antarctica

Becki Hills

29 ‘Vernacular’ Architecture and Embodied Knowledge: On Indigeneity, Development and Climate Change

Ed Davison 33 Digital Aura of Generative AI in the Built Environment: A Brief History from Generative Adversarial Networks to Generative Pre-trained Transformers

Haoxing Xu

45 A Foray into the Criticism of the Covert House by the Imagined Critic, Perry F. Allwright

Stella Saunt Hills

49

Interiorising the Faith Within: The Role of Architecture in the Diasporic Identity and Religious Adaptation of Fo Guang Shan London

Pimchanok Na Patalung

55 Depicting A Heterogenous Story of Shanghai Longtang: An Intergenerational Memory Study of Four Women Connected to Xingye Fang

Qinwen Ding

61 The Property of the Nation: Exploring the Democracy of the Public Spaces of the National Theatre

69 Orienting Schloss Schönbrunn: Phantasms and Orientalism in the 18th Century Court of Maria Theresa

Rodney von Daffer-Jordan

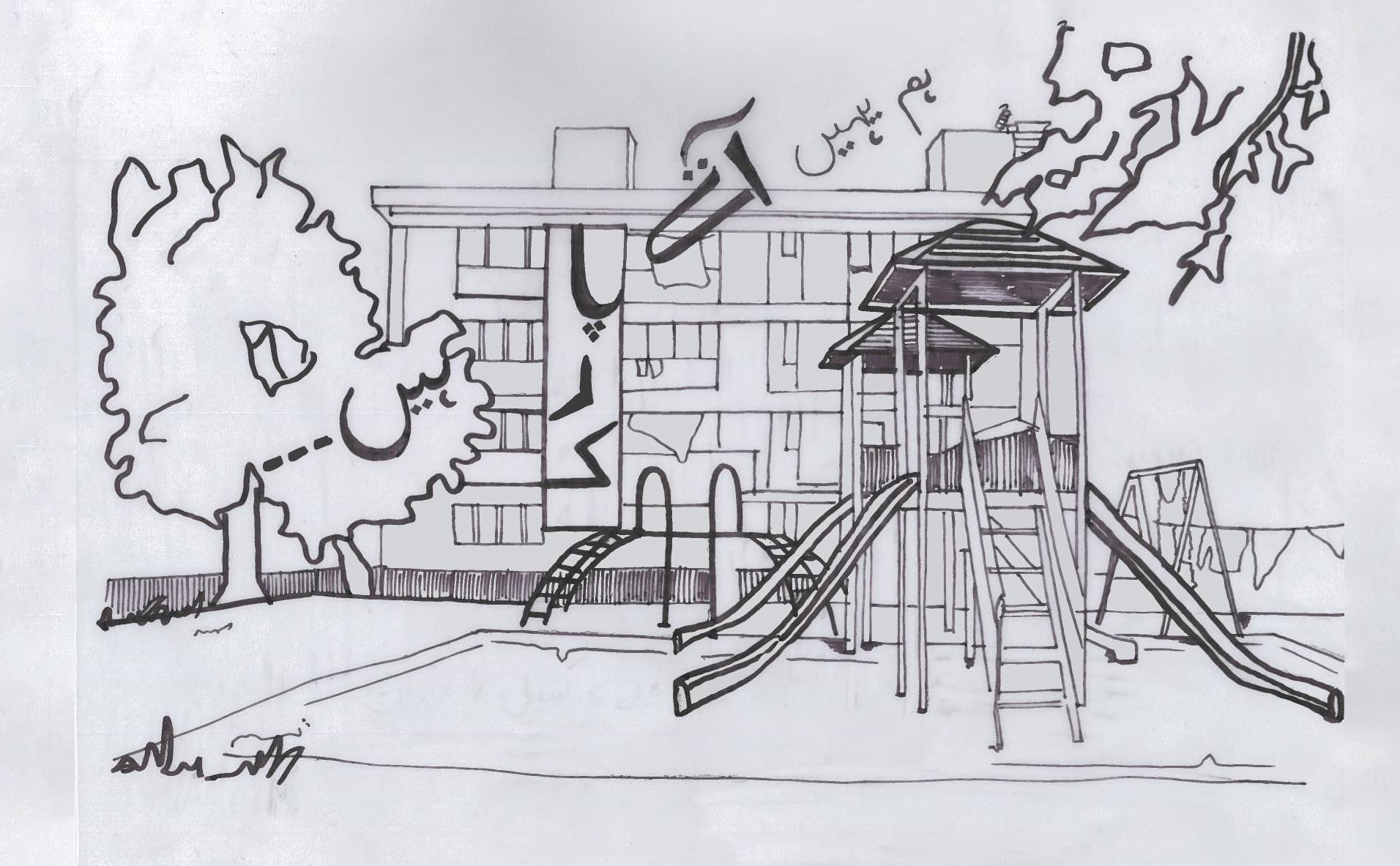

75 A Critical Ethnographic of Ziddi Feminist Socio-Spatial Practices in a Modern-Mohalla of Islamabad

Sidra Khokhar

83

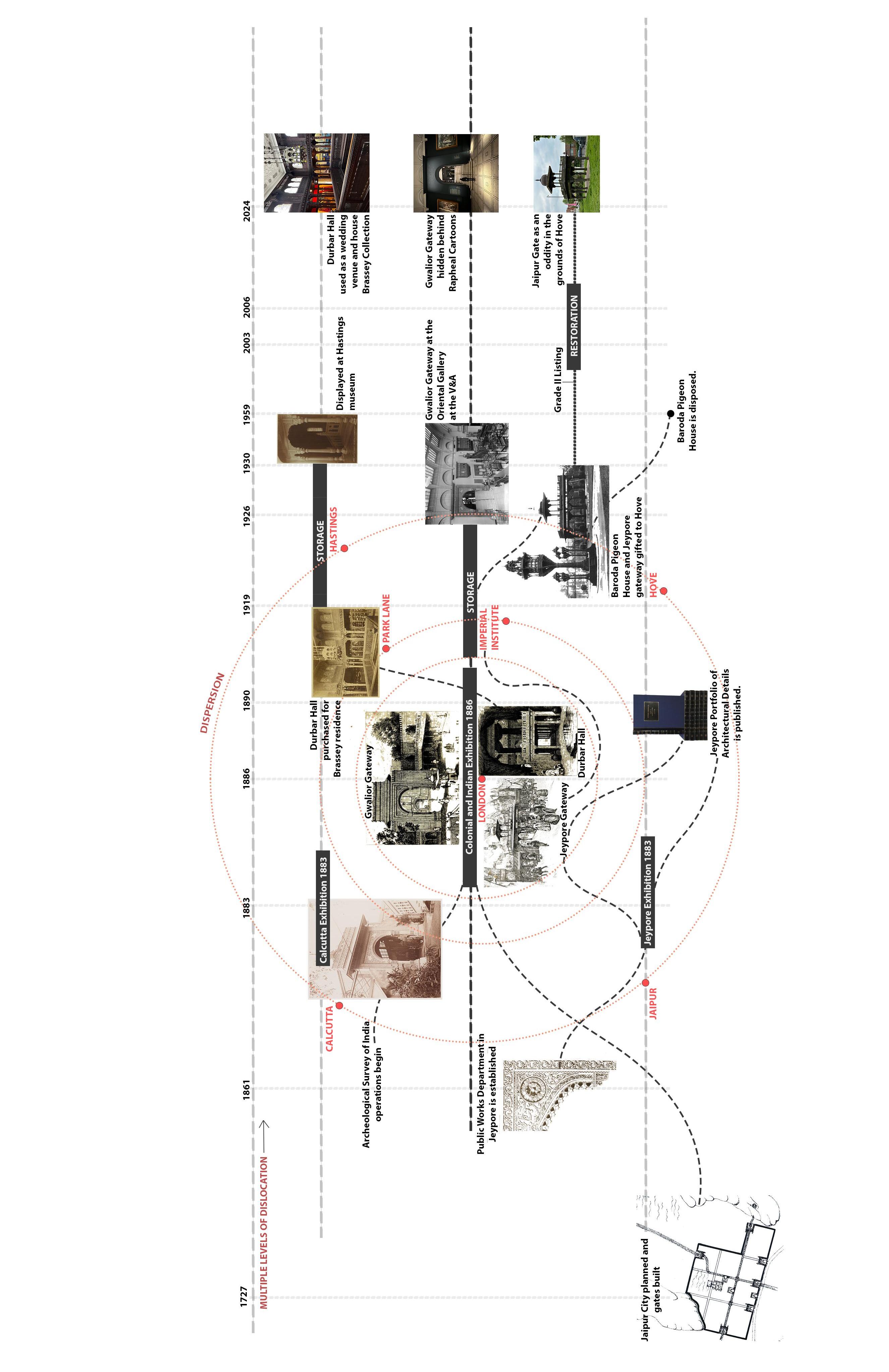

Disentangling: Dislocation, Dispersion and Disassembly in the Surviving Fragments of the Colonial and Indian Exhibition of 1886

Radhika Jhamaria

89 Hang-A-Li on the Pedestal: Constructed Narratives in the Museums of Imperial Japan

Leah Cho

Rodney von Daffer-Jordan

Refracted Geographies reflects the global scope of the research projects by the 2023-24 cohort of the Architectural History MA at The Bartlett School of Architecture and the diverse approaches brought to the programme. Beginning at 22 Gordon Street, our research spans across disciplinary and geographical boundaries, with subjects ranging from colonial anthropologies of Antarctica to constructed images of Asia within Europe. Collectively, we challenge the established canons of architecture, along with its histories and theories, and propose new perspectives for thinking and writing.

The theming is opportune bearing the recent ‘identity crisis’ with the role of the architect and architectural educator. This is reflected within the ongoing debates and internal reflections of the professions, as indicated by the 2024 Decolonising Architecture Symposium at the Royal Institute of British Architects and The Bartlett’s ongoing pedagogical reforms with its new Just Environments cluster. With these developments, the symposium contributes to the current discussion regarding the increased import placed upon architectural dialogues and viewpoints from – and about – the historically marginalised. Thus, by presenting experiments with disparate and hitherto unmapped positions, our cohort brings new outlooks into the light.

In Part I – Architectural Humanities, authors focus on the numerous methodologies for composing histories around the built environment. In Part II – Affective Architectures, authors focus on the intangible connections between spaces and the people who inhabit them. And in Part III – Fragmented Histories, authors focus on rethinking representations of the global majority and their relationship to power.

In Part I, Yanqi Huang analyses the culture of conservation in architecture in postwar Britain with a focus on the contributions of the fourth Viscount Esher in York; Inigo Custers paints a picture of Jean-Michel Folon, a Belgian artist who engaged in modern and postmodern architectural discourses; Elise Enthoven wanders about Covent Garden as she explores its redevelopment in the 1970s and the emotional impact of the changes on its residents; Becki Hills sails to Antarctica to explore Oceanic Colonialism and the impact of human upon nature at Hektor Whaling Station; Ed Davison rethinks ‘vernacular’ architecture and the use of indigenous building methods and their relationship to Modernism and climate change; and Haoqing Xu analyses the uses of Artificial Intelligence within architecture.

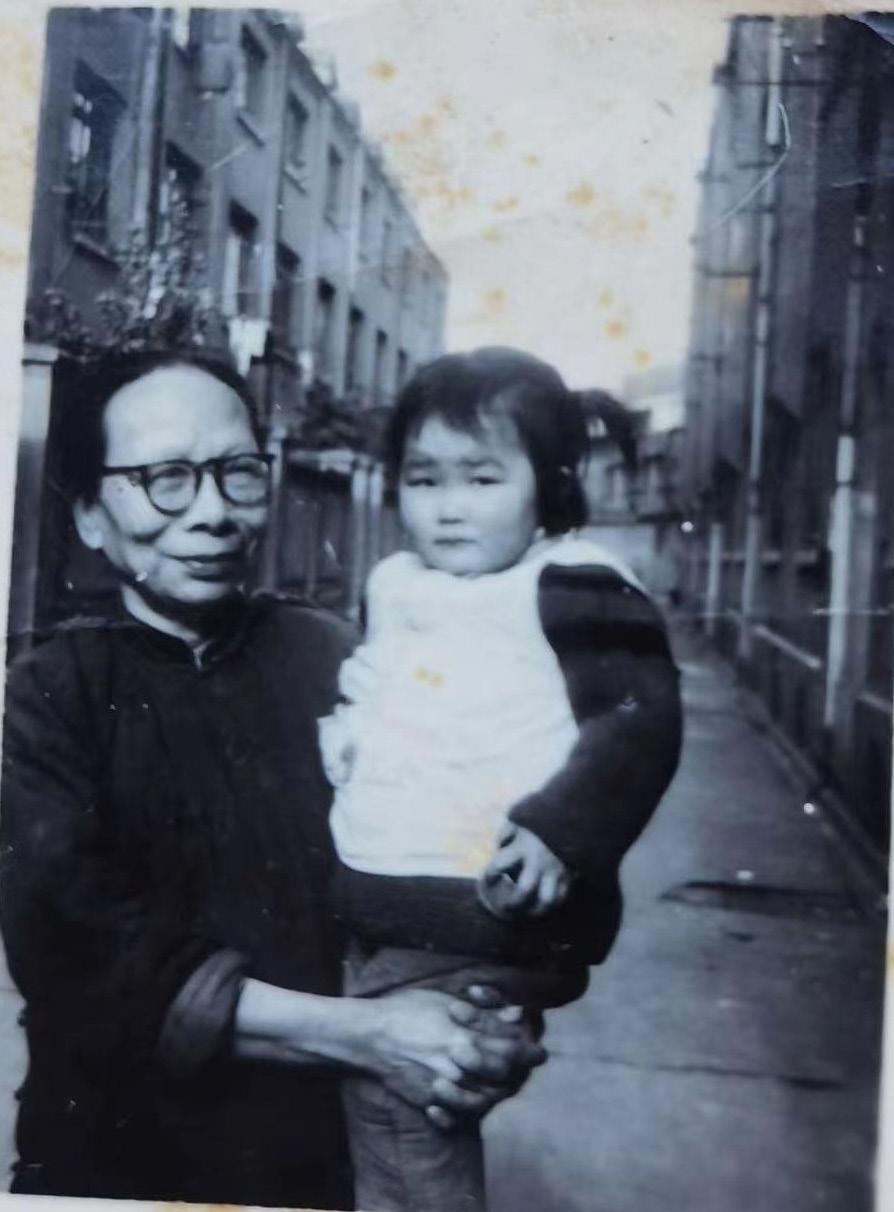

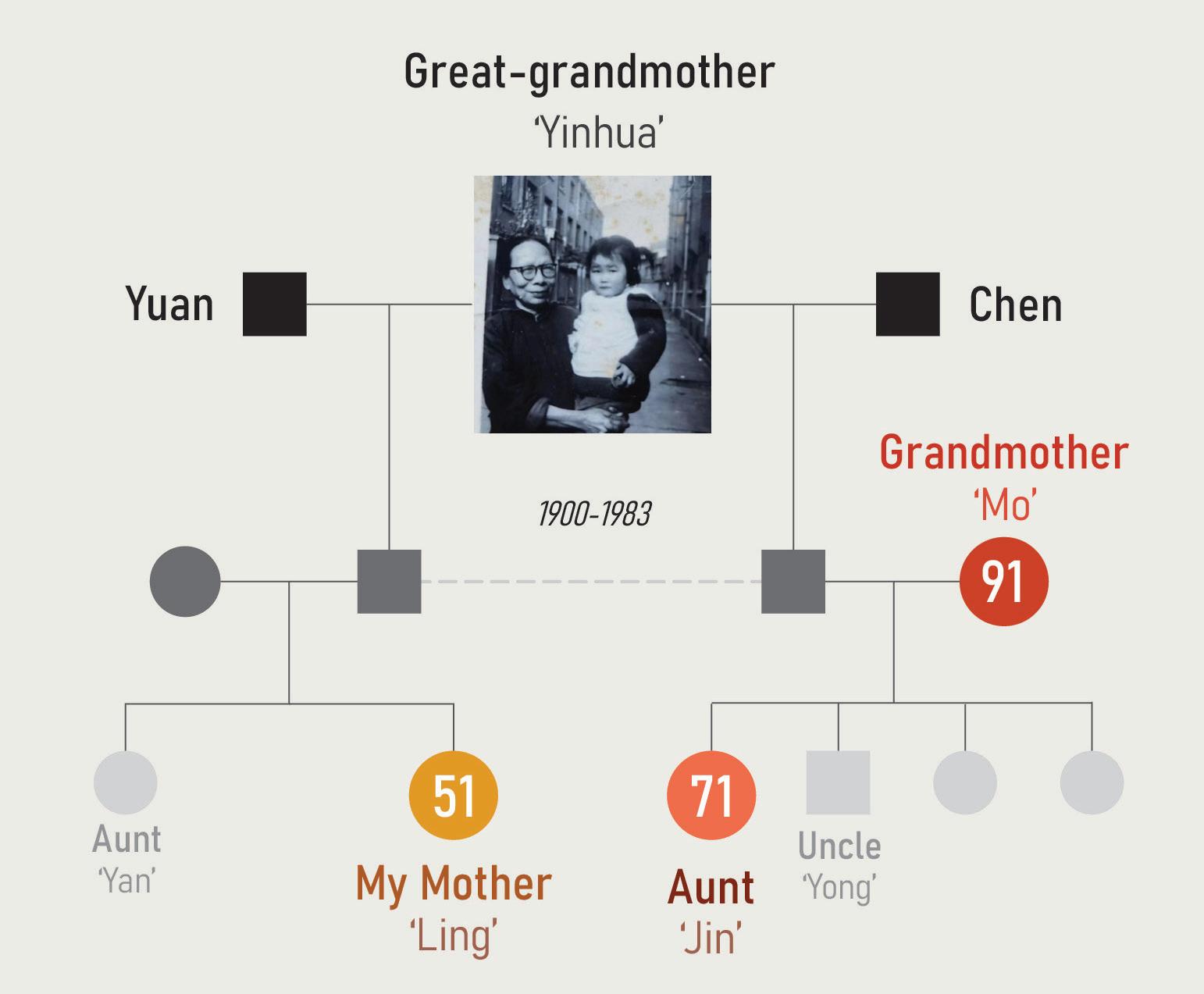

In Part II, Stella Saunt Hills is undercover in their exploration of DSDHA’s Covert House in London through the voice of an imagined critic; Pimchanok Na Patalung opens up Fo Guang Shan London Temple to understand Architectural adaptation and its relationship with identity and religion; Qinwen Ding traces the Shanghai Longtang through the viewpoints of four women from her family; and Catherine Cull Thomas goes backstage to explore the public space of the National Theatre and the role of everyday people in its success.

In Part III, I imagine constructed realities of East Asia through phantasms and Orientalism in Schloss Schönbrunn; Sidra Khokhar traces Mohallas in Islamabad and the practices of women within them; Radhika Jhamaria journeys across the British Empire to explore the present state of artefacts from the Colonial and Indian Exhibition in 1886; and Leah Cho curates a discussion on how artefacts from states conquered by Japan were presented in Imperial museums.

While we have collated these essays into specific categories, each writing holds a nuanced position influenced by the author’s background and influences, highlighting the vast geographical and theoretical spaces we inhabit within the realm of architecture and architectural history.

Yanqi first studied History of Art at the University of York. Following his collaboration on the York C20 Architectural Gazetteer, he wrote his undergraduate dissertation on the post-war operation and professional network of the York City Architect’s Department (1951-96). His research – often inspired by forgotten archives – sheds light on the bygone heroisms in the British twentiethcentury built environment, foregrounding its ‘public-service’ culture and the contested politics between architectural education and professionalism. Yanqi is currently a volunteer caseworker at the Twentieth-Century Society and a selected member of the sixth cohort of New Architecture Writers. He has contributed to the Association for Art History, the Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art and the re:arc institute, among others. He was born and raised in Shanghai.

Elise was born and raised in Antwerp, Belgium. She studied architecture at the University of Antwerp, where she discovered her affinity for architectural history and theory. Additionally, her time in practice at AWG Architects confirmed her interest in exploring the existing urban fabric and its social implications rather than adding new structures to it. As a result of this, she conducted architectural history research for her master’s dissertation, which focused on the 20th-century expansions of the Heritage Library in Antwerp. This experience inspired her to pursue a second master’s degree in Architectural History at the Bartlett School of Architecture. In her dissertation about Covent Garden’s redevelopment, she explored the social implications of architecture, particularly the emotional and psychological experience of space. Right now Elise is active as a pre-doctoral researcher and teaching assistant and wishes to continue to explore her passions for architectural research and education.

Ed Davison

Ed studied architecture at the University of Bath and uncovered a passion for architectural history, before moving to London to study at the Bartlett. Ed’s research has been interested in decolonising canons to challenge dominant architectural paradigms. Particularly, Ed has explored the operation of ‘vernacular architecture’ as a category within architecture culture, tracing the (colonial) Modern legacies of the term. Ed’s work includes architectural design and research, with experience in heritage conservation. Ed intends to continue working as an architectural designer, writer and researcher, aiming to eventually undertake a PhD from his MA research, while developing his practice within the built-environment sector.

Inigo received a degree in Architecture from Ghent University. She first began to research architectural history whilst writing her master’s thesis on Flemish architectural culture in the 1980s and 90s, leading her to pursue the Architectural History MA at the Bartlett. She enjoys discovering untold stories through archival research, especially that of Belgian architectural history. She previously worked as a part-time researcher at Ghent University and is currently a practicing architect in Brussels, where she works on public projects and social housing. She intends to continue working to combine architectural practice and research as the two fields compliment one another.

Haoqing Xu

Becki is a Trainee Assistant Producer at Goalhanger, the UK’s top podcast production company (The Rest Is Politics, The Rest is History, etc.). Becki completed her MA in Architectural History at UCL’s Bartlett School of Architecture, while working as a freelance podcast producer and researcher. Her interests sit at the intersection of climate and social justice, international relations and post-colonial history. Becki also holds an undergraduate degree in International Relations and Politics, achieved in 2019. Becki was the producer and editor of the Nature-based Solutions podcast, a six-part series released by Savills in 2023 focused on making the field of natural capital more accessible, and platforming those working at the forefront of the sector. She also previously worked as a freelance journalist, with articles and short documentaries published by the BBC, The Independent, The Telegraph, TalkRADIO, Holland & Barrett Magazine, The Tab Sheffield, HuffPost and Graduate Recruitment Bureau.

Haoqing completed her BA (Hons) in Architecture at Manchester School of Architecture, where she gained experience in urban renewal projects. Her practical proposal involves designing a secret garden and urban recreational facilities where visitors can escape from busy traffic and commune with nature. Studying architectural history and theory has taught her about wider frameworks of humanities. When centering seas with an oceanic viewpoint in her previous thesis, Hong Kong is depicted as a global transit port in which Chungking Mansion is seen as a heterotopia with entangled relationships across the time and space. Furthermore, technology offers an alternative approach to architectural design and contributes to an anonymous historical narrative. In her dissertation, Haoqing provides an overview of the evolution of Generative Artificial Intelligence technology and critiques some representative AI-based image-making technologies available today.

‘The

Yanqi Huang

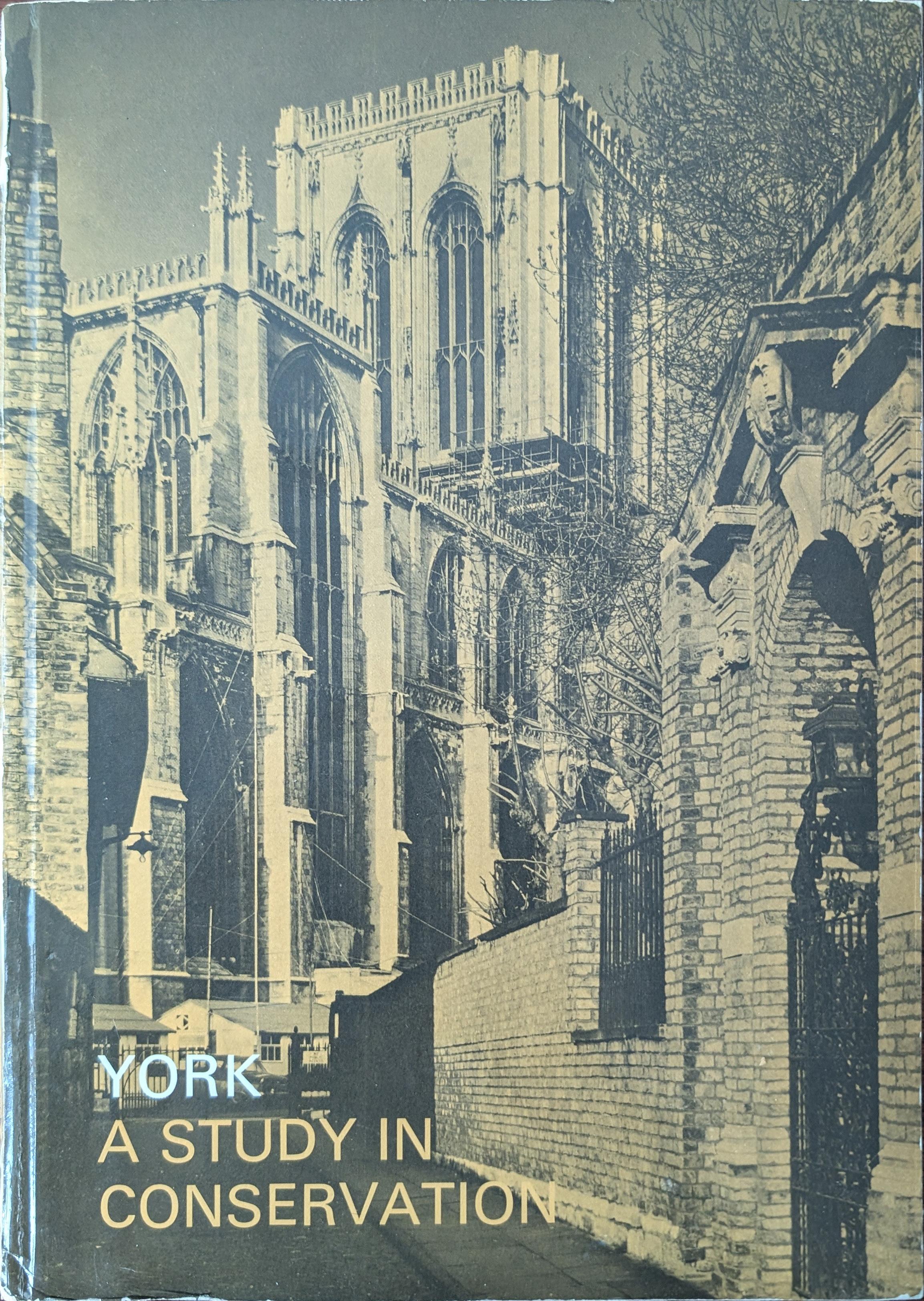

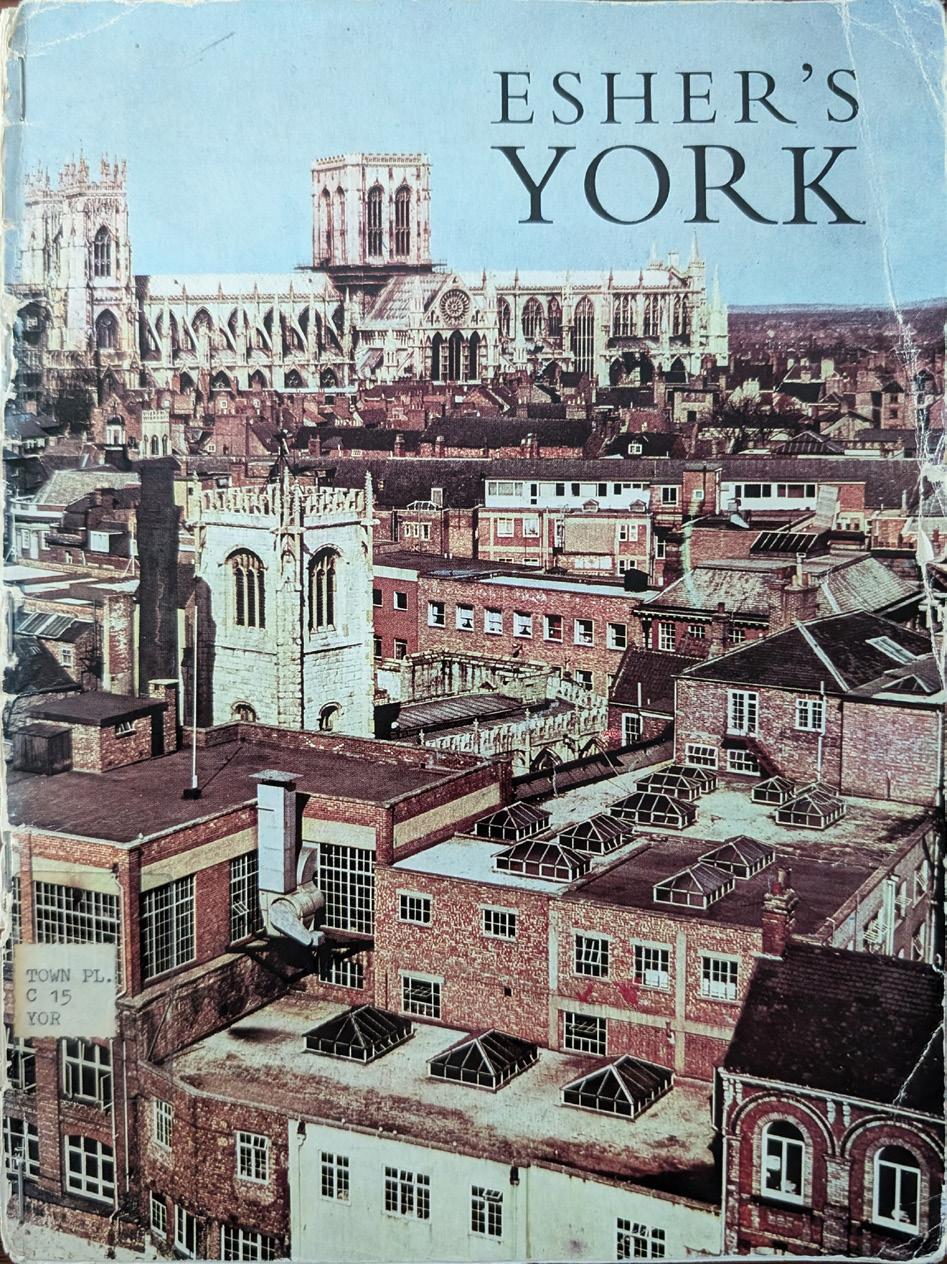

‘The Esher Report’ is the iconic nickname of the architect-planner Lord Esher’s York: A Study in Conservation given by the York Civic Trust, one of its prime local supporters.1 It was one of the four government implication studies on the recent planning legislations in the conservation of historic towns, commissioned in 1966 jointly by Richard Crossman’s Ministry of Housing and Local Government (MoHLG, 1951-70) and the relevant local Councils. The four pilot studies (on Bath, Chester, Chichester and York), officially known as the ‘Studies in Historic Towns’, were initiated in response to perceptions of planning distress in redevelopment schemes of historic town centres across the country. Led by Crossman’s diligent junior minister, Lord Kennet, and advised by a purpose-built Preservation Policy Group at the MoHLG, the ‘Studies’ were ambitious in their conception. The intention – with each of the four towns’ varied and complex conditions (both physical and political) – was to bring together different tendencies of thought in conservation to inform future legislation.2

Nonetheless, after its successful publication in 1969, the Esher Report has long been a missing chapter in the architectural historiography. It was primarily due to the Report’s unfortunate fate at the end of the 1960s, when the majority of its recommendations were rejected by the stubborn York City Council, with the promised Government aid revoked amid bureaucratic changes. Therefore, the Esher Report has been read and omitted as a story of ‘disappointment and failure’, but as this history unfolds, it shall be a charming one.3 First, Esher, whose life mobilised between architecture and a prescribed public life, was inherently an alluring topic: as put by Otto Saumarez Smith, Esher’s dual identity made him ‘one of the central cogs in the prosopographical machine of post-war architectural culture’.4 Second, the story of the Esher Report is not wholly characterised by the ‘heroism’ of the 1960s conservation movement – as chronicled by Alan Powers in

Twentieth-Century Architecture (2004) – but multiple protagonists’ resilient belief in conservation as public service, which was later translated into Esher’s nuanced method for York and the local amenity societies’ collective desire to regenerate their walled city.5

This dissertation approaches the story with a biographical lens. Through the personal history of Esher – evidenced by his architectural criticism and multiple written memories – and his local and national intellectual network, this study aims to situate the intellectual processes of the Esher Report from 1964 to 1971 (marked by the beginning and end his personal involvement in York) within the architectural culture of modernism and conservation in post-war Britain, and to expose the intricate relationship between architecture and public service, modernism and conservation, local and national politics. Meanwhile, it draws from a strong base in archival and oral histories, in excavating numerous overlooked collections at the Borthwick Institute, City of York Council, John Rylands Library, Royal College of Art, York Civic Archive and York Civic Trust, and mining unmapped personal tales from the former oral history interviews with three protagonists of this story, conducted by John Gold in 2003.

Endnotes

1 Chris Brayne and Vivian Brooks, ed., Esher’s York (York: Yorkshire Evening Press, 1969). Lord Esher was born as Lionel Brett in Watlington Park. During his long tenure as an architect-writer, he had signed different names, including Lionel Brett, for architectural criticism and personal accounts; Viscount Esher, for public works before 1963; Lord Esher, for public works after 1963 and works as the Rector of the Royal College of Art (1971-78); and, finally, Lionel Esher for his history A Broken Wave: The Rebuilding of England, 1940-1980 (London: Allen Lane, 1981), as a combination of his architectural and public role. While the footnotes respect his different signatures, the main body of this excerpt of the long dissertation will hereinafter refer to him as ‘Esher’.

2 Harry Teggin, interviewed by John R. Gold, 21 Lansdowne Crescent, Glasgow, 21 May 2003.

3 For other tales alike, see Timothy Brittain-Catlin, Bleak Houses: Disappointment and Failure in Architecture (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2014).

4 Otto Saumarez Smith, Boom Cities: Architect-Planners and the Politics of Radical Urban Renewal in 1960s Britain (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2019), 125.

5 Alan Powers, ‘The Heroic Period of Conservation’, Twentieth-Century Architecture, no. 7 (2004): 8-18. It shall be noted: while aspects of the planning history of twentieth-century York (especially in relation to the Inner Ring Road plan) is discussed in this dissertation at times, a comprehensive study of this subject is well beyond the scope of this essay. Only materials in direct relation to the Esher report will be examined and hereinafter cited. Albeit a worthwhile study, no attempt has been made to chronicle the planning history of York further to Bill Fawcett, ‘A Plan for the City of York (1948)’, York Historian 30 (2013): 25-42.

Illustrations

Figure 1. Cover matter, York: A Study in Conservation, 1969. Photographed from a copy of the original (London: HMSO, 1968).

Figure 2. Cover matter, Esher’s York, 1969. Photographed from a copy of the original (York: Yorkshire Evening Press, 1969) held at the University College London Library, London.

Figure 3. Lord Esher at the Opening Ceremony of Bregate Housing, with June Hargreaves, Senior Planning Officer, York City Engineer’s Department (right to Esher, in shades) and John Shannon, Chairman, York Civic Trust (left to Hargreaves, in glasses), 1981. Photographed by David Foster. Courtesy of David Fraser and the York Civic Trust. Bregate Housing was the first phase of the Walmgate Rehabilitation project (1978-83) led by the York Housing Association following the Esher Report. It was designed by the York University Design Unit, a subsidiary of the Institute of Advanced Architectural Studies, York, one of the key local supporters of the research and implementation of the Esher Report.

Figure 4. Lord Esher and Harry Teggin (centre) at the Platform Party after the Public Presentation of the Esher Report at Tempest Anderson Hall, with, from left to right, Honor Jackson (left) and John Shannon (right), 1969. Photographed from a copy of Yorkshire Evening Press (6 Mar 1969) held at the York Explore Archives, York. Harry Teggin, Partner at Esher’s architectural practice Brett & Pollen (1959-71), managed the production of the Esher Report.

In 1971, the Belgian artist Jean-Michel Folon (1934-2005) published an article in the French magazine Preuves, reflecting on his artistic influences. Interestingly, he did not begin his article with a reflection on art, but on architecture. He wrote: ‘Architecture appealed to me. Even today, I think it’s the most important, the most complete, the most necessary art’.1 Although architecture was – as this dissertation will further reveal – a significant factor in the artist’s personal life as well as in his oeuvre, this has not been previously addressed, nor investigated. This dissertation aims to make a start to that investigation.

Folon, a Belgian artist who spent his life living in France, was mostly known for his drawings, watercolour paintings screenprints and – later in his life – his sculptures. Although he was an internationally renowned artist, with monographic exhibitions in the United States, Japan, Italy and other countries, the academic discourse on the artist today remains rather limited. Most posthumous publications so far are published by the monographic museum in La Hulpe, today known as the Fondation Folon, which Folon established himself in 2000. Examples are Folon. Sculpture (2020), Folon and Olivetti (2024), published for an exhibition on his collaborative projects with the Italian Olivetti company and Folon/Magritte (2024), the exhibition catalogue for a temporary exhibition on the similarities between both artists in the Magritte Museum in Brussels. From the field of academia, there are not many publications on the artist thus far. There is the publication L’etica della poesia, published for an exhibition on Folon in The Vatican which has contributions by art critics such as Claudio Strinati and Micol Forti. Furthermore, the Italian art historian Marilena Pasquali has covered the work of Folon in a few publications. Since Folon was a Belgian living in France, mostly successful in the United States, Italy and Japan, it’s difficult to root his legacy in just one specific country. Consequently, –and probably also due to the remoteness of the Fondation Folon, only reachable by car – not all Belgians today have heard of the artist. Although his work definitely relates to the earlier Belgian surrealist movement, Folon remains more widely celebrated abroad, such as in Japan, where a large retrospective exhibition is travelling from Tokyo to Nagoya and Osaka in 2024 and 2025.

Born on the outskirts of Brussels, Folon moved to Paris when he was 21 years old. Interestingly, he studied architecture in high school. He did not enjoy the rigid and conservative way architecture was taught at the school. After graduating high school, he decided to study the newly established degree in Industrial Design at La Cambre Superior Institute of Decorative Arts, founded by renowned art nouveau and modernist architect Henry Van de Velde. Ultimately, Folon would stay at La Cambre for no longer than six months. In March 1955 he packed his bags and hitchhiked to Paris, hoping to make it as an artist in the glorious Ville Lumière Folon thus never became an architect. He did not hold a degree in architecture and he never practiced the profession. However, throughout his artistic career, he presented himself as an architect. Although he only studied at La Cambre for six months, in multiple interviews over the years he claimed he held an architecture degree from the school.2 This is a falsehood. Folon, not an architect, wanted everyone to think he had enjoyed a respected modernist architectural education.

As the archival research in this dissertation will reveal, his relationship with architecture resurfaces in many forms in his life and work. Yet, this has never been addressed. The field of investigation thus still lies wide open, with the archives at the Fondation Folon as the main lead. On the one hand, being the first is a luxury, on the other it poses the challenge of limitation. The aim of this dissertation is therefore twofold. Firstly, Folon’s peculiar personal relationship with architecture and the architectural profession is revealed, arguing that architecture is a major incentive behind the artist’s career, whilst examining his views on architecture through the archival research conducted at the Fondation Folon. This will reveal that next to his identity as an artist, Folon carried with him a second, more hidden identity as an architect. Secondly, a selection of works is examined from an architectural perspective. All works selected testify of a relationship with a specific architectural context, whether that is an architect, a built project, a publication or something else. The comparative cases explore the work of Henri Lefebvre, Saul Steinberg, Ayn Rand, Madelon Vriesendorp, Jacques Tati and Bernard Lassus. Since this is the first piece of writing to be written on the topic of Folon and architecture, the selected works are used as a framework and as a necessary boundary. Together, these associations with the existing canon of architectural history frame the bigger picture of Folon’s (critique of) architecture.

All works discussed here are dated between 1966 and 1986. This means that the historical context of this analysis is that of late modernism, modernist critique and the postmodern turn. The geographical focus is France, although, in the footsteps of Folon, a necessary excursion to New York is also made. France knew rapid modernization and industrialization in the years after the Second World War. With the rise of heavy industries and the consequential migration from the countryside to

the industrial and economic centres, the housing crisis, induced by bomb damage and lack of real estate development during the war, became acute. Consequently, numerous large scale collective housing projects were rolled out on the outskirts of France’s metropolitan areas in the 1950s. These projects, also known as Grands Ensembles, referred to the ideas of the pre-war Modern Movement and the Athens Charter. Quickly however, concerns were raised about the dehumanizing consequences of large-scale building culture. Therefore, although the Grands Ensembles remained the primary form of housing construction during the 1960s and 1970s, their architectural and urban qualities were constantly re-evaluated as the importance of humanism and sociology intensified.3 Regardless, the substantial scale, monotony and rationality of the Grands Ensembles remained the urban paradigm for more than two decades, until they were finally rejected in the midst of the 1970s. Folon often depicted these modern cityscapes – their beauty as well as their alienation – in his artistic oeuvre. The critical themes this dissertation thus touches upon are the ‘americanisation’ of France in the 1960s and 1970s, the social and mental consequences of large-scale modernist urbanisation, the consequential rise in critique of modernism and its rationality and uniformity, as well as the emergence of 20th century starchitecture.

When analyzing Folon’s oeuvre against its historical architectural context, it becomes clear that his works manage to grasp the ambivalences – the ideals, as well as the concerns – present in the French architectural debates. An example is his 1985 mural titled La Porte, which was painted on a Grands Ensembles building block in the thirteenth arrondissement of Paris (figure 1). The building block was part of a large scale regeneration project in the 1960s and 1970s, titled Italie 13. Although Folon often critiqued the alienating effects of large-scale modernist building culture in the works he produced – such as in his covers for The New Yorker – the mural illustrates the discrepancies in Folon’s architectural critique, as, in reality, it embodies the atmosphere of the Grands Ensembles and does not compensate, but rather seems to reinforce the alienating effects of the built environment to which it is applied. In fact, the enormous door seems to replicate the Grands Ensembles’ own megalomania, functioning almost as a billboard for commuters coming from the south, visible from afar. As previously discussed, the ideals of the Grands Ensembles projects were not rejected until well into the 1970s, rather concerns were raised about their psychological and sociological impact, and attention to these issues rose early on. The public opinion rather accepted these new ways of living, whilst also critically evaluating their sociological consequences. It is exactly these public concerns that Folon managed to visualise in his art, without rejecting the fundamental ideals of high-rise modern building culture, representing the ambivalences present in the public debates.

This thesis starts with the emphasis on the fact that Folon was not an architect. But, as this analysis has shown, in a different way, he was. He did not like the type of architecture he saw being constructed in France in the decades after the war, so, disappointed in the state of the architecture of his time, he decided that he did not want to be a contributor. Alternatively, he became an architect outside of the discipline of architecture, producing work which was emblematic for the architectural debates of his time and geographical context. He thus carried with him a second identity, an architectural one, next to his artistic one. It is this architectural identity that resurfaces in many forms in his oeuvre, as well as in his personal life.

Endnotes

1 Quote translated by author : ‘ L’architecture me plaisait. Encore aujourd’hui je pense que c’est l’art le plus important, le plus complet, le plus nécessaire. ‘ Jean-Michel Folon, ‘ Des dessins qui signifient danger ‘ Preuves no. 5 (1971): 136.

2 Example: ‘Folon, who for four years studied at the Higher Institute of Architecture in Brussels, founded by Van de Velde [...]’, Fabienne Deval, ‘ Folon. L’architecte de l’humour. ‘ Les arts graphiques (1972): 19. Quote translated by author : ‘ Folon qui pendant quattre années étudia à l’institut supérieur d’architecture de Bruxelles, fondé par Van de Velde […]. ‘

3 Kenny Cupers, ‘The Expertise of Participation: Mass Housing and Urban Planning in Post-War France’, Planning Perspectives 26, 1 (2011): 29-53.

Illustrations

Figure 1. Photographed by Inigo Custers.

Elise Enthoven

Introduction

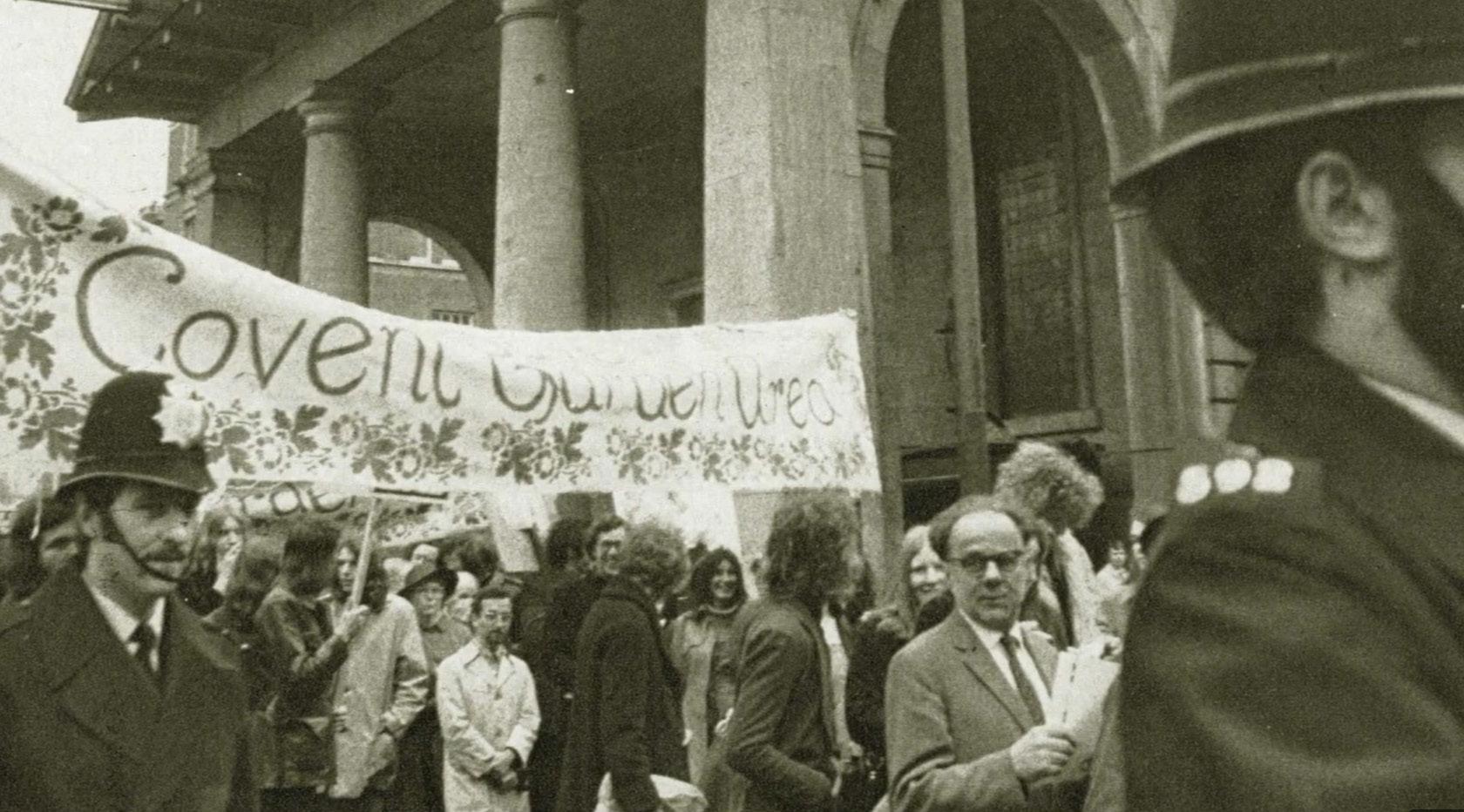

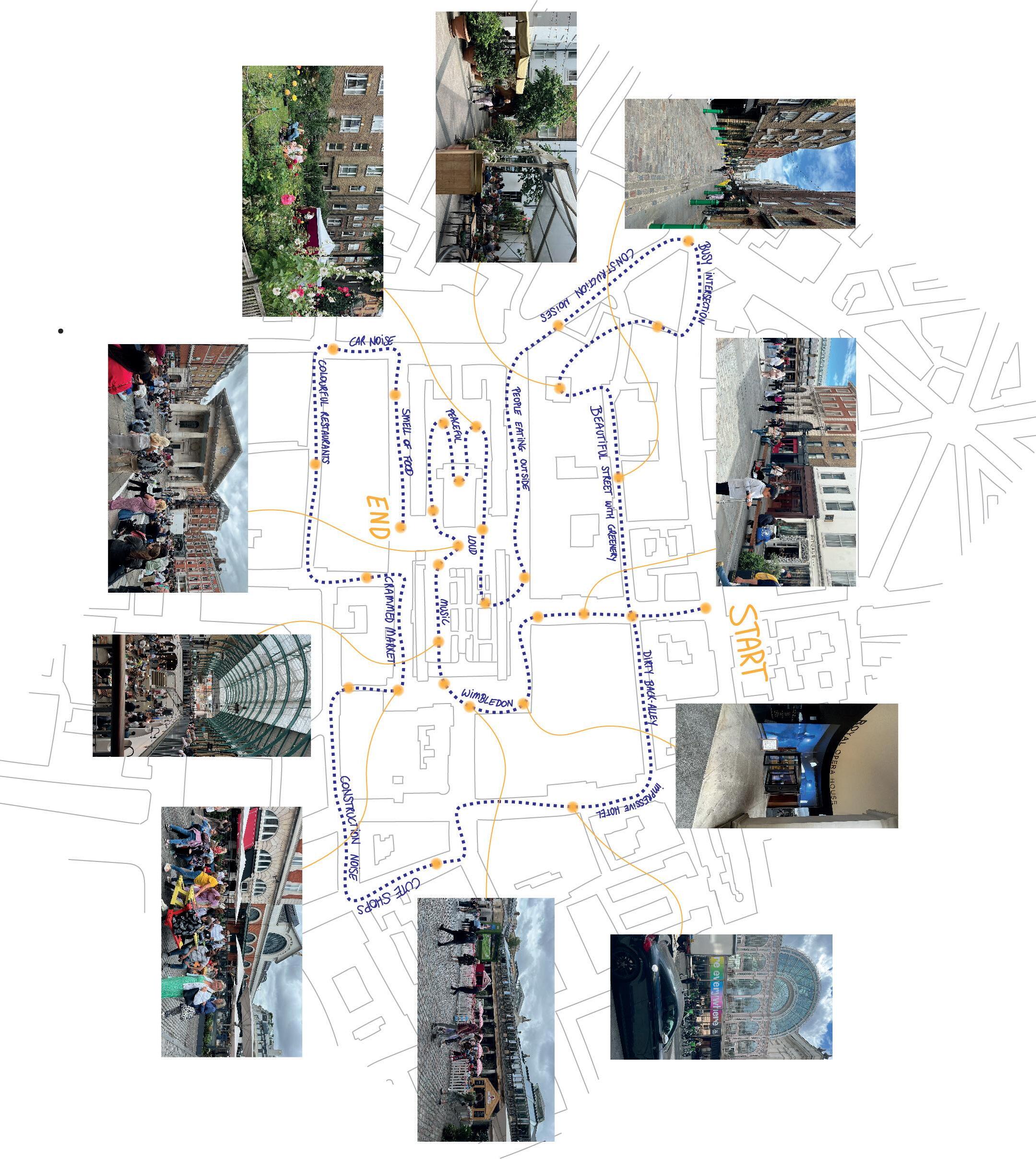

This dissertation explores the emotional experience of the architecture of Covent Garden during its redevelopment between 1971 and 1980, analysing how emotion and sentiment drove protests held against the Greater London Council’s plans.

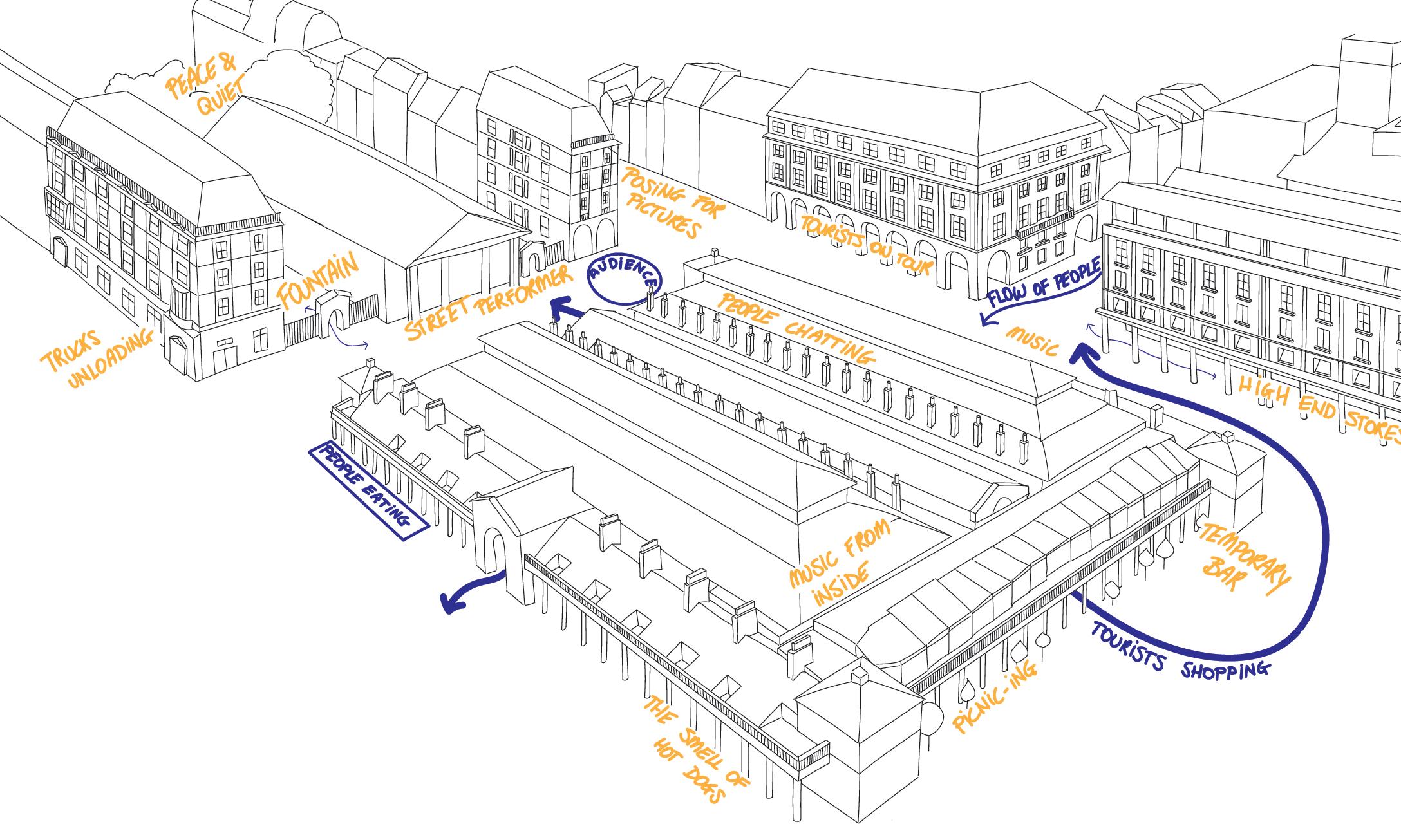

The study began with a psychogeographical analysis of Covent Garden’s presentday state, using the dérive as a research tool to gain a deeper experiential understanding of the area.1 Afterwards, a literature review, oral history and drawing techniques were combined to investigate the interplay between design and human emotions. A first important source includes life writing articles written by King’s College students in 2013, based on interviews they conducted with figures of the Covent Garden protests.2 A second key source is the The Battle for Covent Garden film, also from 2013 and the full recordings of interviews conducted for this film.3 These personal accounts provided insight on the community’s emotional responses to the redevelopment. These testimonies underscore the importance of Covent Garden’s architectural space in shaping social behaviour and public sentiment. The Covent Garden protests illustrate how architecture can influence a community, which in turn actively worked to preserve and shape its architectural environment.

Ultimately, this dissertation explores the importance of considering emotional and psychological factors in urban planning and architectural design. By unveiling how Covent Garden’s architecture affected its inhabitants in the past, the study provides valuable insights for future urban developments, emphasising the need for a more human-centred approach.

The dérive, or drift, from psychogeography was used to gain a deeper understanding about the emotional and psychological effects of the urban environment on its users. By wandering around aimlessly, the attractive or repulsive aspects of the neighbourhood could be identified. Moreover, this approach also

served as a critical lens to compare current issues of the area with the community’s original aspirations in the 1970s.4

The dérive revealed there is a lively atmosphere around Covent Garden, especially in the pedestrianised streets. This atmosphere depends heavily on its image as a tourist attraction. The appeal to both international and domestic tourists has to do with the range of different types of culture on offer, from high arts such as ballet and opera to street performers and popular culture.5 Additionally, global brands such as Apple and Shake Shack bring in a lot of different people. However, the presence of these major brands has also created a homogenised experience of any high street, which threatens the unique local experience.6 Their presence thus also causes some dissatisfaction with the local residents.7 Although the local community agrees that development is good and has even helped certain businesses such as chips shops and pubs, the general consensus among the neighbours is the fact that a lot of the area’s previous character has been lost.8

The second part of the dissertation focused on the redevelopment period between 1971 and 1980. Primary research involved collecting and analysing personal testimonies from individuals who lived and worked in Covent Garden during the 1970s. Sources included literature, such as I’ll fight you for it: behind the struggle for Covent Garden by Brian Anson,9 archival material, such as life writings found in the City of Westminster Archives10 and interview recordings provided by Digital Works, who were partners on the The battle for Covent Garden film from 2013.11

In the 1960s, the Covent Garden fruit- and vegetable market was bursting out of it seams, causing major traffic jams in the centre of London. Consequently, in 1966, it was decided that the market would move to a new building in Nine Elms. As a result, a team was formed between the Greater London Council, the Westminster City Council and Camden to design a redevelopment for the whole area, stretching 96 acres.12 A first plan was published in 1968; it suggested monumental developments rising from the sites of demolished terraced buildings. The ground level would be given over to the car, including a four-lane highway parallel to the Strand. Public transport would be elevated above the ground level and the whole structure itself would become a tourist attraction.13

People were appalled by the idea that the GLC could just swipe in and demolish their neighbourhood. They were scared to lose their homes14 and that the ‘whole area would have been decimated’.15 However, Covent Garden benefited from the fact that the area had curated such a strong community already. Generations

of families had lived in the area and all knew each other; ‘walking around the neighbourhood unnoticed was an impossibility.’16 The amount of council housing and the presence of the market resulted in a kind of ‘village atmosphere’17 where doors were kept unlocked and neighbours would just walk in for a chat.

Under the leadership of a young architect, Jim Monahan, and a former GLC architect who had worked on the redevelopment plans, Brian Anson, the Covent Garden Community Association was formed. Together, people found the strength to stand up for the little guy, determined to fight for the area’s and the community’s preservation.18 They organised marches and demonstrations, printed posters, squatted in buildings, and so on. Eventually, a Public Inquiry was held on the 7th of July, 1971. It took almost two years to reach a decision but eventually, 250 buildings in the area were added to the list of historical and architectural merit. This put a stop to the most radical GLC plans.19 The move of the market however, could not be stopped and in 1974 the area was left ‘dreadful, awful, like a ghost town’.20

After this initial battle had been won, the CGCA set up the Covent Garden Forum, a team that would work together with the GLC to redesign the redevelopment plans. They reached an agreement where the market building would be transformed into a galleria, where retail spaces were provided for small, independent shops in order to keep the unique character of the area.21 However, in the early 2000s, Covent Garden changed ownership.22 Since then, big brands have slowly taken over from the quirky shops, turning the area into a typical high street, much to the dissatisfaction of some members of the Covent Garden community.23

Conclusion

This dissertation wished to demonstrate the importance of considering emotional and psychological factors in urban planning and architectural design. As proven by the Covent Garden case, architecture always influences emotions, behaviour and social interaction.24 The built environment of Covent Garden, with its history and identity, curated a strong sense of community for local residents, workers in the theatre trade and the market vendors. Thanks to this communal experience of the architecture and atmosphere it created, they also felt a sense of communal rage when the GLC published their plans to demolish this precious area. Together, they were strong enough to stand up to the bureaucracy; they were led by ‘youthful ignorance’,25 even when they weren’t always confident that their campaign would be successful.26 Their battle illustrates the importance of resisting economic and aesthetic pursuits with no consideration for the experiential consequences. This case has implications for the wider field of urban design and proves the need for inclusive, community-centred approaches.

1 Guy Debord, ‘Theory of the dérive’, Les Lèvres Lues, 1956.

2 Life writing, 2013, 2976. City of Westminster Archives, London.

3 Digital Works, The battle for Covent Garden film, Covent Garden Memories, 2013 http://www. coventgardenmemories.org.uk/page_id__114.aspx?path=0p40p.

4 Debord, ‘Theory of the dérive.’

5 Adrian Guachalla, ‘Perception and experience of urban areas for cultural tourism: A social constructivist approach in Covent Garden’, Sage Publications 18, no. 3 (2018): 299.

6 Karen Kice, GLOBAL vs. LOCAL: Exploring Architecture as a Local Brand for Covent Garden (Los Angeles, CA: University of California, 2011), 6.

7 Life writing of Harry Goody, 2013, 2976/8, City of Westminster Archives, London. https://archives. westminster.gov.uk/Record.aspx?src=CalmView.Catalog&id=2796&pos=1.

8 Harry Goody, interviewed by St Clement Danes pupils, 2013, interview 5C, recording, Digital Works, London.

9 Brian Anson, I’ll fight you for it: behind the struggle for Covent Garden (Suffolk: The Chaucer Press, 1981).

10 Life writing, 2013, 2976. City of Westminster Archives, London.

11 Interview by St Clement Danes pupils, 2013, recording, Digital Works, London.

12 Anson, I’ll fight you for it, 17-20.

13 Judy Hillman, The rebirth of Covent Garden: a place for the people (London: Greater London Council, 1986), 15-17.

14 Harry Goody, interviewed by St Clement Danes pupils.

15 Lynn Barker, interviewed by St Clement Danes pupils, 2013, interview 8A, recording, Digital Works, London.

16 Life writing Lyn Barker, 2013. Finding number 2976, Lyn Barker 2976/4, City of Westminster Archives https://archives.westminster.gov.uk/Record.aspx?src=CalmView.Catalog&id=2796&pos=1

17 Life Writing Bernard O’Connor, 2013. Finding number 2976, Bernard O’Connor 2976/13, City of Westminster Archives https://archives.westminster.gov.uk/Record.aspx?src=CalmView. Catalog&id=2796&pos=1

18 George Skeggs, interviewed by St Clement Danes pupils, 2013, interview 11A, recording, DigitalWorks, London.

19 Anson, I’ll fight you for it, 71-73, 90.

20 Barker, interview.

21 Hillman, The rebirth of Covent Garden, 23.

22 ‘About us’, Covent Garden London, n.d. https://web.archive.org/web/20120923202808/http:// www.coventgardenlondonuk.com/about.

23 Life writing of Harry Goody, 2976/8.

24 Tricia Austin, Narrative Environment and Experience Design: space as a medium for communication (Oxford: Routledge, 2020), 112-113.

25 Jim Monahan, interviewed by St Clement Danes pupils, 2013, interview 12A, recording, DigitalWorks, London, 17:44-17:50.

26 David Bieda, interviewed by St Clement Danes pupils, 2013, interview 1A, recording, DigitalWorks, London, 5:53-6:33.

Illustrations

Figure 1. The community marches, 1972, in Brian Anson, I’ll fight you for it: behind the struggle for Covent Garden, (Suffolk: The Chaucer Press, 1981) 112.

Figure 2. Covent Garden present-day state. 2024. Drawing by Elise Enthoven.

Figure 3. Psychogeographical walk. 2024. Drawing by Elise Enthoven.

Becki Hills

‘There is a fine line between acknowledging the extent and seriousness of the troubles and succumbing to abstract futurism and its effects of sublime despair and its politics of sublime indifference.’1

Marine ecosystems are governed by circulations. From the currents which transport nutrients across the globe to the more-than-human species responsible for maintaining oceanic food chains, any disruption to these millennia-old cycles can precipitate ecological collapse. Yet, as a result of the Antarctic commercial whaling industry during the twentieth century, this is precisely what happened to cetaceans and their co-dependent aquatic worlds. Whaling has taken many forms over the past thousand years, from local subsistence whale hunting in the eleventh century to industrial pelagic whaling at the end of the nineteenth century. However, following the invention of the exploding harpoon by Svend Foyn in 1870 and the erection of land stations across the Antarctic continent, the whaling landscape monumentally shifted, and cetaceans risked total annihilation at a genocidal scale. When the northern waters of the Atlantic and Arctic became depleted, attention shifted south, to Antarctica, where millions of whales spend the summer feeding before migrating to warmer climates to breed.

The Antarctic commercial whaling industry decimated cetacean populations across the Southern Ocean, with scientists estimating ‘that nearly 2.9 million large whales were killed and processed during the period 1900–99. Of this total … 2,053,956 [were killed] in the Southern Hemisphere.’2 Within this figure, we can estimate that over half a million whales were processed at the Hektor Whaling Station on Deception Island.3 Alongside the decimation of cetacean pods, the main food group of countless polar species – Antarctic Krill – was dramatically depleted due to the sudden scarcity of whale excrement which had once fertilised the waters of the

Southern Ocean and sustained the Krill. Here, the power of ecological circulations and entanglements in maintaining an aquatic equilibrium are painfully evident. Amid the escalating planetary crisis, understanding how anthropogenic actions unravel ecosystems is crucial for the prevention of future interspecies genocide.

Without the development of the modern whaling station, however, this oceanic genocide would not have been possible. While the invention of the exploding harpoon in 1870 revolutionised the number of cetaceans factory ships were able to catch, the development of mass aquatic abattoirs across the Antarctic peninsula sustained the burgeoning industry, ensuring its profitability and commercial success. Prior to the erection of whaling stations across Antarctica, whalers were forced to conduct their operations from factory ships with limited processing space for more than two to three whales. This meant that any additional whales were often rendered abject, left to decay in the waters in which they were captured. Upon the arrival of materials to build whalers accommodation, large copper boilers for the melting of whale blubber into oil, and ports from which to moor whaling ships, the industry boomed, and whaling became one of the most profitable industries on the planet. Across the Antarctic continent, several whaling stations were erected by British, Norwegian, Chilean and Argentinian whaling companies; however, very little research has been conducted into the role of such necropolitical architecture in advancing the industry. While numerous architectural histories focus on abattoirs and other material sites of interspecies violence and extermination4 across the world, there is little evidence of any architectural histories pertaining to Antarctic whaling stations. Therefore, this dissertation aims to occupy this space, depicting the Hektor Whaling Station on Deception Island as a material example of interspecies oceanic colonialism.

I began developing the theory of interspecies oceanic colonialism within a previous piece of work focused on the whaling station ruins of the Shetland Islands in Scotland.5 The framework seeks to move beyond the human and land-based boundaries of traditional definitions of colonialism, instead foregrounding the terms ‘interspecies’ and ‘oceanic’ as lenses through which to view the oppression and subjugation of more-than-human species by human actors at sea, as well as on land. More specifically, interspecies oceanic colonialism involves the domination and exploitation of marine species through methods such as occupying aquatic and terrestrial environments, acts of violence against more-than-human species by human actors, and engaging in practices of extractivism which are tantamount to genocide. An interspecies approach is inclusive of the impact of humans upon more-than-human species, moving beyond anthropocentric histories. Similarly, an oceanic perspective serves to broaden generally accepted terracentric

understandings of colonialism, seeking to include acts of colonial violence, extractivism and occupation which occur within the aquatic realm. The whaling station ruins on Deception Island, this dissertation argues, serve as one of the clearest material examples of interspecies oceanic colonialism in the Antarctic. Due to the perilous and expensive nature of Antarctic travel, along with the damaging environmental impacts of tourism in the region, I was not able to visit Deception Island to undertake a first-hand spatial analysis of the former whaling station site. I was, however, able to make a trip to the former ‘the center of international whaling’, Sandefjord in southern Norway. Having gleaned from Dibbern’s commercial history of Deception Island that, at its height, ‘The concentration of whaling activity at Deception was so dense that the anchorage also gained the nickname of “New Sandefjord”’, I travelled to the town to gain a first-hand perspective on the extent of whaling activity once undertaken and overseen from its shores.6 The history of the twentieth century whaling industry is memorialised in architectural and artistic iconography throughout the town, with sculptures, museums and memorabilia at every turn. Comparing the whaling operations at Deception Island to those of Sandefjord, therefore, brings to life the extent of the architectural apparatus erected on Deception Island during the early twentieth century. In occupying Deception Island’s terrestrial space through the Hektor Whaling Station and using it as a base from which to exploit the surrounding marine ecosystems, human actors were able to engage in violence, extractivism and genocide against cetacean populations, leading to the site becoming exemplary of interspecies oceanic colonialism and paving the way for the decimation of cetacean species.

This dissertation seeks to delve into and examine the entangled stories of interspecies oceanic colonialism on Deception Island throughout the past one hundred years, with the ambition of warning against future acts of anthropogenic violence and the dangerous attitudes of human exceptionalism. Beginning with the history of the Hektor Whaling Station on Deception Island, I will construct an architectural history of the site through a critique of terra- and anthropocentric definitions of colonialism. Following this, this dissertation will develop the theoretical framework for interspecies oceanic colonialism, using the Hektor Whaling Station as an archetypal site of anthropogenic violence. The theory will also be constructed through a critique of Raphäel Lemkin’s 1944 definition of genocide, arguing that the ensuing Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide serves to exclude more-than-human species from legal protection against acts of slaughter. This will be exemplified through an analysis of the practices carried out by Antarctic whalers on Deception Island during the early twentieth century. Violence, territorial occupation and extractivism sit at the heart

of the theory of interspecies oceanic colonialism, with the Hektor Whaling Station offering illustrative material examples of each of these necropolitical acts. Building upon Achille Mbembe’s theory of necropolitics, this dissertation will extend his theoretical framework in order to move beyond the original concept’s terra- and anthropo-centric limitations. I will also draw upon theories of extractive capitalism and Donna Haraway’s notion of the Chthulucene later in this dissertation to bring the concept of interspecies oceanic colonialism into the present day. This approach seeks to shed light on the long-term exploitation of cetaceans and other marine life by humans in the Antarctic. Ultimately, this dissertation aims to develop an interspecies architectural history of the Hektor Whaling Station, arguing that acts of genocidal colonialism and extractivism do not belong merely in the realm of interhuman violence. Rather, by developing an understanding of the multispecies entanglements which underpin the very existence and continuation of our planet, we can ensure that more-than-human species are granted the legal and ideological protection they deserve in a time of planetary crisis.

Endnotes

1 Donna J. Haraway, ‘Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene’ (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2016): 55.

2 J. R. C. Rocha, P. J. Clapham and Y. Ivashchenko, ‘Emptying the Oceans: A Summary of Industrial Whaling Catches in the 20th Century’, in Marine Fisheries Review, 76, no. 4 (2015): 37.

3 Einar Abrahamsen, ‘Whaling Station, Prince Olaf Harbour, South Georgia’, accessed via National Archives CO 78/196/5, Hector Whaling Ltd.: new lease of land at Deception Island (1935), https:// discovery.nationalarchives.gov.uk/details/r/C3317680, accessed 12 Jun 2024.

4 See José María Fuentes et al., ‘Public Abattoirs in Spain: History, Construction Characteristics and the Possibility of Their Reuse’, Journal of Cultural Heritage 16, no. 5 (2015): 632–39 and Yi-Wen Wang and John Pendlebury, ‘The Modern Abattoir as a Machine for Killing: The Municipal Abattoir of the Shanghai International Settlement, 1933’. Architectural Research Quarterly 20, no. 2 (2016): 131–44.

5 Becki Hills, Silenced Songs: The Erosion of Former Whaling Stations on the Shetland Isles, (The Bartlett School of Architecture, University College London, 2024).

6 Visit Norway. ‘The Whaling Monument’, Visit Norway (n.d.), https://www.visitnorway.com/listings/ the-whaling-monument/3303/, accessed 14 Jun 2024.

Illustrations

Figure 1. Photographed by Becki Hills.

Figure 2. Adolf van der Laan, The harpooned whale turns and tosses while being stabbed, 1725.

Ed Davison

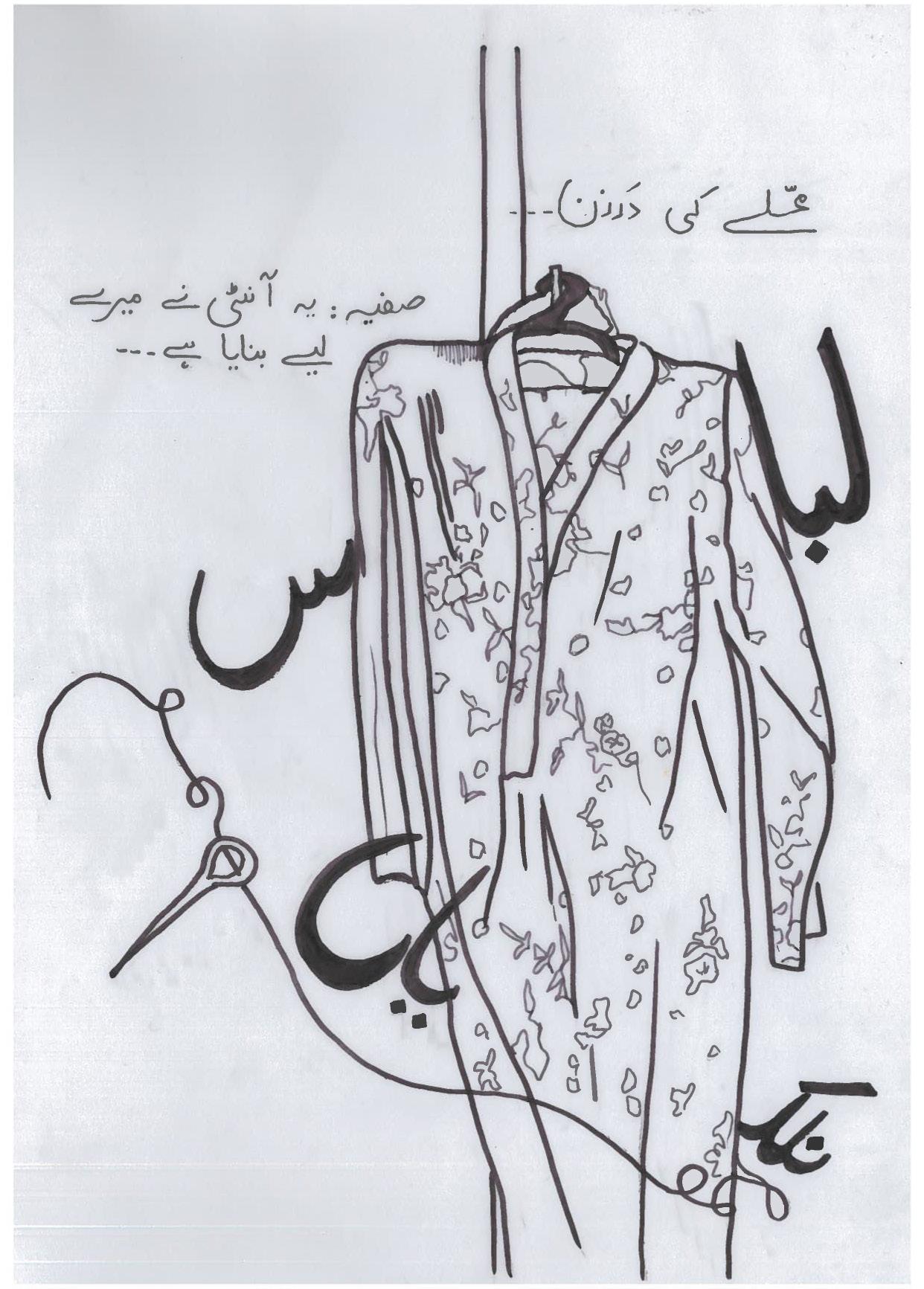

My research is concerned with discourses on ‘vernacular’ architecture in Western architectural history. The term ‘vernacular’ architecture is generally understood to mean buildings built using local knowledge with local materials by people without formal professional training. From its earliest coinage, it was associated with the architecture of the ‘Other’, constructed as a category to define those outside of the mainstream architectural culture. The value of ‘vernacular’ lay in its perceived timelessness and its availability for architects to claim, and its association with sustainability has contributed to a renewed relevance in the age of climate crisis. My research takes three key moments in the history of ‘vernacular’ architecture, starting with writings by Maxwell Fry (1946, 1982)1 and Bernard Rudofsky (1947, 1964),2 and concludes with contemporary publications on ‘Vernacular’.3 My analysis charts the uncanny proximity of racialised bodies within representations of the ‘vernacular’ while tracing categorical slippages surrounding ‘vernacular’ architecture, including associations with the non-western (geographic), the tropical (geo-climatic), the racialised (bodily), the primitive or timeless (temporal), closer to/ utilising natural resource (natural), growing naturally (organic), of indigenous peoples (anthropological).

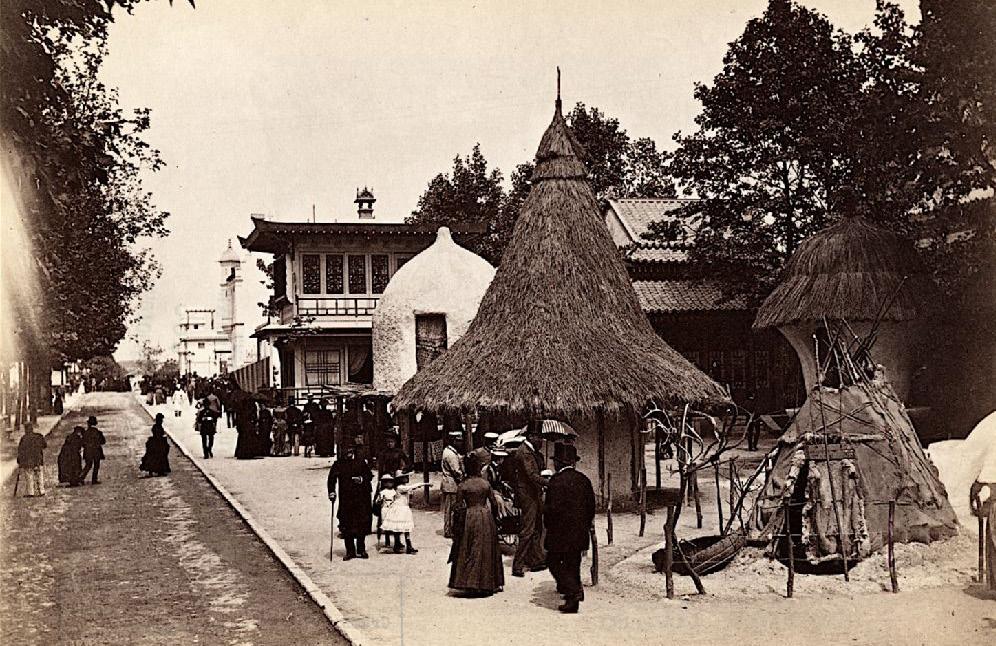

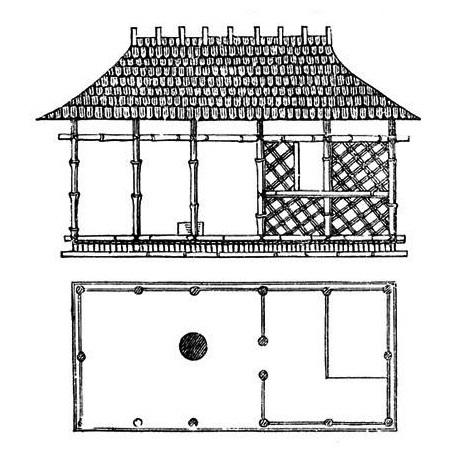

Discussions of ‘origins’ and the mythic ‘primitive hut’ are familiar in architectural history.4 For Gottfried Semper, clothing and architecture developed alongside oneanother through the tectonics of weaving. Architecture becomes an extension of clothing in his principle of ‘bekleidung’. Semper saw confirmation of his theories in a Caribbean hut present at the Great Exhibition of 1851. The importance of the Caribbean hut was in its availability for representation, in confirmation of his own preconceived ideas, and not in its concrete reality.5 Laying out a genealogy

of ‘primitive’ in architecture, Adrian Forty outlines its influence on Modernism and describes the prevailing interest amongst architects in uncovering the essential character of things.6 As early as Vitruvius’ writings on the ‘primitive hut’, ideas of the ‘vernacular’ were being invoked as articulation of difference and the search for authenticity.7 Caught precariously within this nexus, but seldom discussed, is the ‘native’ body. Often presented alongside the Adamic hut is the question of nudity and clothing.8 The colonial study of anthropology, exemplified by L’Habitation humaine exhibition at the 1889 Universal Exposition in Paris9 (Fig. 1) underpinned many influential works, including Charles Darwin’s.10 The ‘native’ body appears in the significant, racist architecture treatises of Adolf Loos and Eugene-Emmanuel Viollet le Duc. Philippa Levine writes that the colonial obsession with the native body surrounded its nakedness, as indication of either savagery or childlike innocence, as well as its erotic potential.11 The ‘native’ architecture of the colonies was placed upon display within ‘native villages’,12 which included colonised subject dressed in ‘native costume’. To quote Anne A Cheng, the notion of ‘Western modern personhood as inherited from the Enlightenment [is] generally understood to be organic, individualistic, masculine, and white. […] [T]hat ideal has always been deeply embroiled with, not just opposed to, a history of nonpersons.’ 13

The Modernist cultural milieu in which Jane Drew and Maxwell Fry worked absorbs and perpetuates many colonial-era positions including its underlying racialism.14 While their built work drew superficial inspiration from local craft cultures, their oeuvre is firmly Modernist, with Fry noting there was little architecture to be found in West Africa, where they were working.15 They attained authority to write about the tropics through their reputation as Empire architects, and their work at the Department of Tropical Architecture at the AA in the 1950s.16 Fry wrote a paper on Vernacular Architecture at the 1982 Passive and Low Energy Conference in Bermuda, laying out a racialised development timeline with European ideas at the leading edge, consigning tropical and desert regions to developmental stagnation.17 Jiat-Hwee Chang notes that notions of climatic design in the tropics in this period were based on a ‘mechanistic and reductive understanding of thermal comfort’, which contributed to the belief that thermal stress hindered socio-economic development.18 Standing apart from Jane Drew’s writing, Fry’s written oeuvre demonstrates an unchanging position from the beginning of his career, when he wrote Architecture for Children, and the end. Recent interest in Tropical Modernism, including the 2024 exhibition at the V+A museum, focuses upon techniques of passive ventilation in Fry and Drew’s architecture, and asks what lessons can be applied today.19

Bernard Rudofsky’s career, while ostensibly reacting against the culture of Modernism as he saw it, continued to operate through key mainstream practices, while seeking to re-invigorate it through invocations of ‘other’. His first exhibition at MOMA, entitled Are Clothes Modern? (1944-45),20 came after an unsuccessful proposal for an exhibition on Vernacular Architecture. When Architecture without Architects opened in 1964, Aldo van Eyck and Team 10 had been exploring similar themes for years21 Architecture without Architects22 continues to influence the world of architecture, particularly within early years of architectural training,23 yet he anthropological and ethnographic content of the earlier Clothes Modern? forms an integral subtext to Architecture without Architects. He draws heavily upon colonial tropes of the racialised other to illustrate his points, finding notable precedent in the writings of Adolf Loos. Rudofsky’s obsession with pre-industrial, ‘unmodern’ cultures involved continual essentialisation and ‘othering’, stripping them –often literally through visual imagery – of any veneer of modernity. The native in ‘vernacular’ for Rudofsky, is not allowed to be modern and definitely not on their own terms, represented through colonial imagery on ‘native’, ‘primitive’ cultures.

‘Vernacular’ architecture and a changing planet

‘Vernacular’ architecture is invoked with renewed relevance in recent publications as a solution to Anthropocenic climate change.24 Following the logics of the development industry and the business of the Global aid-funded knowledge economy,25 highly charged details from the intertwined histories of colonialism and the Anthropocene are omitted. Appropriating ‘indigenous’ knowledge into the structures of the Global aid-funded knowledge economy, the white western expert is positioned as an authority in humanity’s need to work together against climate change. Kathryn Yusoff’s A Billion Black Anthropocenes or None draws close attention to the collective amnesia in accounts of the Anthropocene, a weaponised innocence and ignorance to the influence of the past.26 Through the impetus of a ‘growing demand for resources’, the urgency of climate change and the moral authority of sustainability, cultural difference and critical histories are flattened and denied. Through the editorial framing and organising structure, which follows the Köppen-Geiger climate classification, a division is created between the global North and South. This is reinforced by choice of visual content, which reveals an underlying pattern of racialisation. Reflecting a broader cultural trend, the familiar racialised development timeline, with European ideas at the leading edge, has become absorbed into an ostensibly post-race and post-colonial world.

In the early examples presented, the racialised logics underlying the author’s position are apparent: ‘primitive’ people are compared directly against modernity,

which invariably is seen as the domain of the West. In recent publications, the legacy of these logics remains through subtle and uncanny associations. ‘Vernacular’ architecture retains an association with ‘primitive’, and the nonWest, only now it is not made explicit, but instead is indexed through the uncanny presence of racialised bodies in photographs, the logics of Development and a humanistic view on climate change. These notions build upon the historic conflation between the non-West and civilisational backwardness, well as a flawed sociotechnical notion of thermal comfort, dating from the mid-twentieth century,27 in which climate is held as key determinant of development. These positions fail to account for the history of colonisation, neo-colonial development schemes which placed newly independent countries under loans designed to be extractive, or the ongoing operations of cultural hegemony which privilege the white metropolitan expert. Such ambivalence to global histories normalises and legitimise the logics and violences of colonialism.

I suggest vernacular architecture is invoked in two differing but concomitant ways – that of being an available technological resource for the purpose of environmental regulation and control, while simultaneously being presented as belonging to an atavistic other. It is presented on one hand as the living, timeless tradition of the un-enlightened masses, and on the other, as a historic, originary stage of the evolution of European architecture. With the continuation of the easy association between indigeneity and ‘vernacular’, the phrase ‘vernacular’ remains charged with historic racialisation, reinforced by its opposition with the white, masculine products of modernism. Of course, these impacts are greatly increased by a relative lack of up-to-date, critical scholarship on non-Western architecture, when compared with the West. Through this, it becomes clear that ‘vernacular’ architecture cannot be analysed without an intersectional framework which critically engages with the assumptions and the epistemic violences taking place. Without sufficient acknowledgement of the historic epistemic violences of this position, it is all too possible for it to be interpreted and appropriated for this end.

Endnotes

1 Jane Drew and Maxwell Fry, Architecture for Children (London: George Allen & Unwin Ltd, 1946) and ‘Mankind’s early dwellings and settlements’, in Passive and Low Energy Alternatives 1, eds. Arthur Bowen and Robert Vagner (New York, Pergamon Press Inc., 1982), 3-8 – 3-11.

2 Bernard Rudofsky, Are clothes modern? An essay on contemporary apparel (Chicago, IL: Paul Theobald, 1947) and Architecture without Architects: An Introduction to Non-Pedigreed Architecture (New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 1964).

3 Sandra Piesik, ed., Habitat: Vernacular Architecture for a Changing Climate (London: Thames and

Hudson, 2017), Christian Schittich, ed., Vernacular architecture: Atlas for Living Throughout the World (Basel: Birkhauser, 2019) and Mark Steven Smoot, Huts: The vanishing rural traditions and vernacular architecture found in 1980s Southern Africa (2022).

4 Joseph Rykwert, On Adam’s house in paradise: the idea of the primitive hut in architectural history (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 1972).

5 Adrian Forty, ‘Primitive’, in Primitive: Original Matters in Architecture, ed. Jo Odgers, Flora Samuel and Adam Sharr (Abingdon: Routledge, 2006), 9.

6 Ibid., 4.

7 Robert Brown and Daniel Maudlin, ‘Concepts of Vernacular Architecture’, in The SAGE Handbook of Architectural Theory, eds. C. Greig Crysler, Stephen Cairns and Hilde Heynen (London: SAGE Publications Ltd, 2012), 346.

8 Philippa Levine, ‘States of Undress: Nakedness and the Colonial Imagination’, Victorian Studies 50, no. 2 (Winter 2008): 191.

9 Irene Cheng, ‘Structural Racialism in Modern Architectural Theory’, in Race and Modern Architecture, eds. Irene Cheng, Charles L. Davis and Mabel O. Wilson (Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 2020), 147.

10 Jimena Canales and Andrew Herscher, ‘Criminal Skins: Tattoos and Modern Architecture in the Work of Adolf Loos’, Architectural History 48 (2005):237.

11 Philippa Levine, ‘States of Undress: Nakedness and the Colonial Imagination’, Victorian Studies 50, no. 2 (Winter 2008): 191.

12 Ibid.

13 Anne A. Cheng, Ornamentalism (New York: Oxford University Press, 2019), 4, EBSCOhost.

14 Cheng, ‘Structural Racialism in Modern Architectural Theory’, 134-152.

15 ‘What is Tropical Modernism?’ V&A, https://www.vam.ac.uk/articles/what-is-tropical-modernism, accessed 31 Jul 2024.

16 Jane Drew and Maxwell Fry, Village Housing in the Tropics (London: Lund Humphries, 1947).

17 Jane Drew and Maxwell Fry, ‘Mankind’s early dwellings and settlements’, in Passive and Low Energy Alternatives 1, eds. Arthur Bowen and Robert Vagner (New York: Pergamon Press Inc., 1982), 3-8 – 3-11.

18 Jiat-Hwee Chang, ‘Thermal comfort and climatic design in the tropics: an historical critique’, The Journal of Architecture 21, no. 8 (December 2016), 1171.

19 Christopher Turner, ‘An architecture school for a new nation’, V&A Magazine (Spring 2024), 39.

20 Bernard Rudofsky, Are clothes modern? An essay on contemporary apparel.

21 Forty, ‘Primitive’, in Primitive: Original Matters in Architecture, 9.

22 Rudofsky, Architecture without Architects.

23 Yasemin Aysan and Necdet Teymur, ‘“Vernacularism” in architectural education’, in Vernacular Architecture, ed. Mete Turan (Aldershot: Gower Publishing, 1990), 302-371 and Wayne Forster, Amanda Heal and Caroline Paradise, ‘The vernacular as a model for sustainable design’, in Lessons from Vernacular Architecture, ed. Willi Weber and Simos Yannas (Oxford: Taylor and Francis, 2013), 203-211.

24 Piesik, Habitat

25 Sebastian Loosen, Erik Sigge and Helena Mattsson, ‘Introduction’, ABE Journal, no. 22 (2023): 4.

26 Kathryn Yusoff, A Billion Black Anthropocenes or None (Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 2018), 16-18.

27 Jiat-Hwee Chang, ‘Thermal comfort and climatic design in the tropics: an historical critique’, The Journal of Architecture 21, no. 8 (December 2016): 1171-1197.

Illustrations

Figure 1. Charles Garnier and A. Ammann, L’Habitation humaine exhibition at the 1889 Universal Exposition in Paris. National Gallery of Art, Washington DC.

Figure 2. Gottfried Semper, Caribbean hut. Der Stil, 2, p. 276.

Haoqing Xu

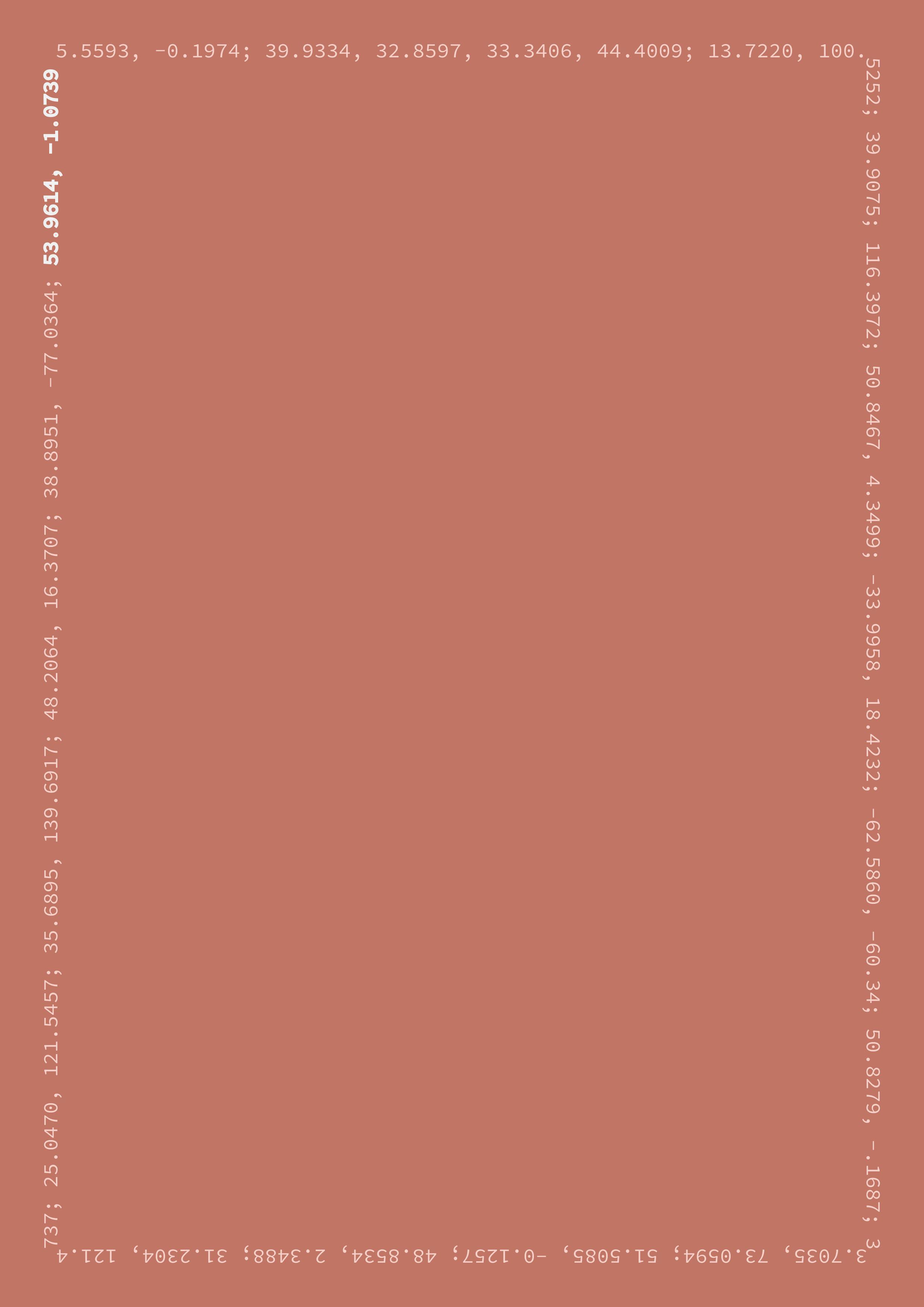

In the mid-2010s, the machine-learning revolution entered the field of visual arts. Later artists discovered the generative adversarial networks (GANs) was particularly suitable for image manipulation. GAN is a new mode of generative AI which demonstrates the capability of manipulating images based on pixels. The emergence of deep learning based generative artificial intelligence (AI) began in the summer of 2022, with the groundbreaking Generative Pre-trained transformers (GPTs) such as Dall-E that create pictures from language prompts.

In the architecture industry, generation of digital AI images has become an indispensable phenomenon, driven by the development of generative AI models. By illustrating the evolutionary painting tools and the modes of production in the historic perspective, the thesis challenges traditional methods of creating art and calls for a new vision and understanding of generative AI as a creative tool in the fields of design and art.

The thesis will express the changing styles and methods of digital generative AI that have shaped architecture over the past decades. There are two ways to analyse generative AI in architectural content, from the aesthetics and productive modes in the order of historic timeline.

The history of painting tools evaluated from traditional painting equipment to digital design applications, which roots in the changing productive relationships. Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels discussed the term ‘reproduction’,1 whereby he believed the time and labour of humans can be reproduced in the form of capital. Walter Benjamin’s concept of ‘the work of art designed for reproducibility’2 reminds the future mode of production in terms of art where ‘mechanical reproduction of art changes the reaction of the masses towards art.’3 In the mechanisation mode of

production, Sigfried Giedion innovatively argues that the mechanisation contributes to the ‘anonymous history’, where on the broader, often anonymous forces that shaped technological and social change. Technology, as a central discourse, form historic memories, produce innovative perspectives.

In light of the contemporary situations of evolving forms of digital art and evolutionary digital technologies, particularly AI and machine learning, an evaluation of the form of Benjamin’s ‘aura’4 in the machine-learning production of art is necessary. However, generative AI imitates artwork from the originals, derivates artistic styles from the dataset, and creative processed content via transformers. In contrast to the era of industrialisation where unidentifiable copies are massproduced, AI algorithms can produce art in seconds. In Carpo’s essay Imitation Game, a critical awareness of invention from AI is predicated on some form of assimilation or imitation.5 Drawing on Benjamin’s ‘aura’6 is a means to understand the phenomenon of mass reproduction in the era of mass customisation where each reproducible product can be identifiable and unique.

The motivation to explore generative models as a design technique for architecture could be the desire to find an alternative design methodology. Before the emergence of diffusion models, AttnGAN has shown an attempt to use text to image neural networks aiding in design process in architecture.7 This approach to architecture design relies not on images but on languages as a starting point, as stated by Matias del Campo in Ontology of Diffusion Models published in 2024.8 Moreover, ControlNet was invented in 2023, which revealed the veil of the potential of diffusion models.9 ControlNet can effectively control stable diffusion with single or multiple conditions, with or without prompts, therefore, diffusion model is a progressive model being able to evolve itself.

Challenging traditional dualism, tools are the only cultural products designed to produce something else. The adaptation of emerging techniques and technologies in the progress of civilisation has been crucial, as gleaned from the historic discourse on technologies. However, in the end, it is the human mind that decodes the various meanings, and cultural products present in the imagery produced by diffusion models because machines do not understand the underlying meanings in images.

To parallelise cultural reproduction and mechanical reproduction, Pierre Bourdieu introduced the concept of culture reproduction. Art has become a cultural capital in Bourdieu’s discourse. He carries on Marx’s historical materialist viewpoints from the Frankfurt School, where artworks belong to the superstructure of a culture.

Similarly, Benjamin examined the capacity of mass production, especially in the era of photography and film, to contribute to aesthetics and politicising art. Benjamin’s The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction, which can be enlarged and therefore extends the ideas of the Frankfurt School, fills the gap to remind us that there is still optimism among the masses and thus positivism in mass culture.

The conclusion of this image testament via ControlNet acts as an experiment and to test the hypothesis that there is the continuity from GAN to GPT, and from 2D to 3D, with a users’ end starting point to reveal the veil of the algorithms. The team lead by Ulyanov et al. separated the digital ‘style’ and ‘content’ of one image, they found an even better solution that successfully transferred styles.10 Here the notion of ‘style’ recalls the reference to the styles of architecture created no matter by different architects or times. As the deeply analysed logics and scientific reasons behind an image, the generated images have a solid foundation to be believed they are reliable and meaningful.

AI can handle the rhythm and poetic sections of video production. Sora uses a diffusion model to create realistic and imaginative scenes from text instructions, demonstrating processes at a higher level with consistent characters and realistic elements. The character in Air Head features a man with a balloon for a face who is walking in a cactus store, which is created by imitation and modification of the original balloons and suits. The transformation and the mix of the originals are like surrealist painting skills that magnificent contrasts among the elements. The essential elements and their textures bring up resonance in an imagined scene. Referring to the gestures of modernism, Zumthor mentioned, the feeling of the door handle in his home is the most memorable memory. ‘What the use of a particular material could mean in a specific architectural context’ asked by him, ‘[…] throw new light onto both the way in which the material is generally used and its own inherent sensuous qualities.’11 The composition of textures and materials brings up the unique existence of the space and time, which is the missing aura in mechanical reproduction.

The aesthetic evaluation of AI-generated artefacts in Tim Fu’s Studio influences the viewers’ perception. This may lead to decreased credits for the human artist and the increased credits for the technological creators. Future works are needed in ways to quantify and diversify the outputs, in terms of understanding generative AI’s influence on aesthetics. The value of generative AI lies not only in its ability to create artistic works but also in its potential to democratise video creation, making it accessible and inclusive for everyone.

The present research tested the hypothesis that digital style and content have been imitated by generative AI. Traditional artworks have an aura that has been lost in the era of mechanical reproduction, in photos and films, but the aura is back in generative AI images. The limitation of the present research is that there is already an aura in many architects’ drawings and creations, and the research lacks a comparison between the aura created by humans and that created by generative AI. However, these two kinds of auras have minimal differences because they are like two artists using different painting tools.

Regarding the relationship between human labour and machines, there is a question of whether humans should adapt tools or whether tools should be invented to meet humans’ needs. As the answer is neither of these, painting tools—as tools of cultural production, a top superstructure above the modes of production, a significant opposite of the mechanical reproduction—will be the tendency of Generative AI models such as GANs and GPTs to boost creativity and possibility in artworks, which helps generate identities and self-recognition and reconnect the lost humanity in nature in the previous era of digital manual drawings to the light of AI and deep learning in almost every industry.12

Endnotes

1 Karl Marx, Capital Volume III: The Process of Capitalist Production as a Whole, ed. Friedrich Engels (New York: International Publishers, 1999), chap. 15.

2 Walter Benjamin, ‘The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction’, in Illuminations, ed. Hannah Arendt, trans. Harry Zorn (London: Pimlico, 1999), 218.

3 Ibid., 227.

4 Ibid., 214.

5 Mario Carpo, ‘Imitation Games’, Artforum 61, 10 (Summer 2023): 185.

6 Benjamin, ‘The Work’, 218.

7 See Matias Del Campo, ‘Ontology of Diffusion Model’, in Diffusions in Architecture: AI and Image Generators (London: Wiley, 2024), 44-54.

8 Matias Del Campo and Sandra Manninger, ‘Strange, But Familiar Enough: The Design Ecology of Neural Architecture’, Architectural Design 92, no. 3 (May 2022): 38–45.

9 Lvmin Zhang, Anyi Rao and Maneesh Agrawala, ‘Adding Conditional Control to Text-to-Image Diffusion Models’ (Preprint, submitted on 26 November 2023),

10 Dmitry Ulyanov et al., ‘Texture Networks: Feed-forward Synthesis of Textures and Stylized Images’ (Preprint, submitted on 10 Mar 2016).

11 Peter Zumthor, Thninking Architecture (Baden: Lars Muller, 1998), 11.

12 Haoging Xu was unable to present at the 2024 MAAH Symposium, but has been included within the accompanying publication per her request.

Illustrations

Figure 1. Created by Haoqing Xu. The Timeline of AI Development. Sep 6, 2024.

Figure 2. OpenAI. Air Head • Made by Shy Kids with Sora. 5 Apr 2024. Youtube Video. https://www. youtube.com/watch?v=9oryIMNVtto.

Figure 3. OpenAI. Tim Fu • Sora Showcase. 18 Jul 2024. Youtube Video. https://www.youtube.com/ watch?v=y_4Kv_Xy7vs

Stella Saunt Hills

Stella received a degree in History of Art and Architectural History from the University of Edinburgh where their dissertation analysed lesbian urban histories in London. Their work at the Bartlett continued this theme, producing a dissertation on lesbian gravesites as portals connecting us to the past. They are interested in urban histories and historical representations of marginalised groups. Stella intends to continue developing their phenomenological and affective research methods in the pursuit of challenging conventional methods of architectural criticism and the dissemination of spatial analysis.

Pimchanok has one strength, and perhaps a challenge: she has a broad interest in everything related to architecture, art, communities and books. This has made it difficult for her to define herself, as she continually develops a diverse background working as an interior designer, writer, content creator, researcher and communicator. In addition to these roles, she is also a keen reader, artist, traveller and fortune-teller. Pim has published articles on her home city, Bangkok, as well as on design and Japanese temples, for magazines like Dsign Something and House Hub. Her life is best lived when driving social change and working with communities and organisations to tackle housing insecurity. A crucial part of Pim’s academic identity is her passion for religious spaces. Building on this, she founded Wadsabi, a blog on Japanese temples and gardens, which led to her first book, set to be published next year.

Qinwen Ding

Catherine Cull Thomas

Qinwen studied architecture at the University of Toronto, Daniels Faculty of Architecture. Having worked at an architecture firm where she gained experience in design, modeling and construction plans, she was drawn to the Architectural History MA as a means of bridging the divide between her intellectual interests and professional training. She believes that interpreting architecture through a combined anthropological, sociological and political science lens allows for a deeper understanding of a building’s connection to human life. She also believes that architecture is fundamentally about people as it is always the people who use a space that gives building meaning. In future, Qinwen intends to research vernacular architecture, domestic spaces and the overlooked episodes in China’s architectural development.