Healing Gardens:

Landscape Architects

Designing for Children’s Wellbeing

Shivani Kandalgaonkar (a1882768)

G4.1.1 St.2.

Designing Research 2024

The University of Adelaide

‘The architect was not seen just as a doctor but as a shrink, the house not just a medical device for the prevention of disease, but for providing psychological comfort.’1

-Beatriz Colomina & Mark Wigley

Summary

The implications of healing inspired by nature is a broad field of research that has given rise to the concept of healing gardens. Researchers have recognised importance of outdoor therapeutic recovery via healing gardens in children’s hospitals. I argue that healing gardens are influential spaces that positively impact children and help in determining how they are responding to an illness within the hospital. I conclude that landscape architects have a significant role to play with respect to the design of the healing garden and can consider the Lady Cilento Children’s Hospital as a successful case study for healing gardens.

Word Count- (99 words)

Healing Gardens: Addressing the Misapprehensions

Even though the subject of healing gardens is widely popular amongst architects and researchers, the assessment of healing gardens is often debated. It is a misconceived notion that every garden heals or provides a sense of mental restoration, therefore ealing gardens do not have any significant capacity with regards to curing its inhabiting patients. While children are too young to experience any mental stress as compared to adults, the purpose of a healing garden for children is questioned.

However, I strongly argue that healing gardens favourably reduce the stress and cortisol levels in children, in comparison to any other landscaped spaces, thereby impacting the recovery rate for curing the illness or any physical pain. I argue that healing gardens can potentially offer healthcare benefits in the most despairing cases or traumatic hospital environments, especially for children.

‘What distinguishes a therapeutic garden from all other gardens? It is the process of design.’2 In support of this statement by Marcus C. Cooper, I contend that landscape architects have the most challenging role in determining the success of a healing garden. An example of a children’s hospital demonstrates how healing gardens impact positively children, and why children need a healing garden within a hospital.

Lady Cilento Children’s Hospital: An Abundance of Healing Gardens.

A case study of The Lady Cilento Children’s Hospital corroborates the above-mentioned argument that healing gardens play an extremely vital role in promoting recovery, and must be provided in every children’s hospital. The Lady Cilento Children’s Hospital is a twelve-storied medical institution in Brisbane featuring eleven healing gardens. Designed by Conrad Garett, the hospital relies on the healing characteristics of nature, by providing multiple healing gardens and restorative outdoor spaces. One of the main reasons for the design’s success is because, more than 75% of the area is allocated for healing gardens, recreational and restorative activities.3 The healing gardens feature over 46,000 individual plants, eight garden shelters, 12 green monoliths, and 33 epiphyte columns.3

The landscape architects have relied on a salutogenic wellness approach that focuses more on the health of the patients rather than the disease. The intention was to establish a positive memory within children’s minds about hospitals and medical treatments.3 The healing gardens are designed for various purposes that cater to a specific type of children, their families and the medical staff. The massive landscaped plaza provides an inviting welcome into the building. The George Gregan Playground in front of the plaza creates a playful environment for children facilitating a positive mood before the treatment. Majority of the healing gardens are located above level five, thus giving a panoramic view of the city. The Secret Garden includes green walls, climbing vines, garden beds, lawns and a number of built features that promote wellbeing.3 The Adventure Garden located on level six has access to physical therapy accessories and tools for children requiring assistance with mobility and physiotherapy. Since the focus is to tackle physical immobility, and assistance with building coordination, the healing garden accommodates a wheelchair-enabled swing, trampoline, wheelchair training facility, outdoor exercise equipment, and a rock climbing wall. The Entertainment Garden features a Kids Zone, Stargazing Room, and fantasy play spaces like Radio Lolipop.3

Apart from the outdoor healing gardens, the interior of the hospital on this level has been intentionally animated for children with human-sized props of tropical birds and animals, suspended floral installations and themed hallways. The Staff Garden is located on level seven caters exclusively to the hospital staff and has fewer play areas, more breakout spaces, sheltered seatings, and outdoor dining spaces.3 The Shared garden is a healing garden with a planting strategy to promote horticulture therapy, enhance biodiversity, and provide a comforting space for its visitors and families. The Babies Garden is a dedicated space for toddlers and their families to engage in playgroup activities and socialising. The Visual Garden accommodates strategies that encourage the plantation of contrast/ accent trees, tactile pathways, and interactive water features. In addition, this garden provides acoustic diversity and visual appeal that nurtures children positively. In one of the healing gardens, the therapeutic benefits of wildlife therapy have been adopted for the benefit of the children. Some of the small interventions for wildlife therapy include planting for birds and creating butterfly gardens.3 In addition to the healing gardens, the hospital has a provision for educational assistance for children of all age groups. These facilities range from outdoor learning to various indoor programs so that the children do not miss out on their education during their stay at the hospital.3

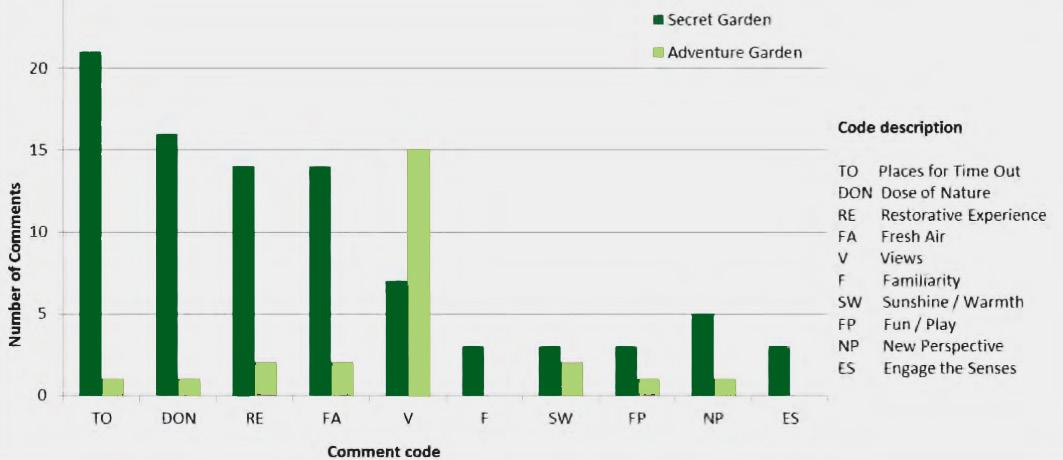

Landscape Architect Katharina Nieberler-Walker (Principal Architect at Conrad Garett Lyons) with Griffith University and Queensland University of Technology conducted a survey to record experiences at the Lady Cilento Children’s Hospital. The survey conducted by the researchers relied on benchmarking diaries/ feedback quotes written by patients, visitors, and staff across different levels within the hospital. This survey demonstrates positive feedback from patients who spent their time in the healing gardens during the treatment.4 The survey documents the responses by various children, visitors and staff recording their natural reaction to the healing gardens (Secret garden, Adventure garden, Staff garden and Babies garden) throughout their treatment.

Ninety percent of the adults (including doctors, hospital staff, and patient families) have recorded a sense of calmness and peace in the healing garden, which they didn’t expect in a conventional medical institution.4 Adults who were presented with a facility like a healing garden demonstrated higher levels of satisfaction with the hospital. The survey advocated that the gardens provide a wide range of visual stimuli, aid in recovery, facilitate fresh air and oxygen, elevate the endorphins hormones within children, and revive olfactory senses. Overall, the survey concluded that healing gardens at the Lady Cilento Children’s Hospital was successful in becoming a safe haven for children undergoing painful treatments or undergoing recovery.

In conclusion, the case study and the survey conducted at the hospital proves that landscape architects are solely responsible for designing efficient healing gardens that can in turn impact the children at the pediatric hospitals. It is also substantiated that access to nature via healing gardens accelerates the rate of recovery amongst children, thereby positively impacting their wellbeing.

The concept of man seeking comfort in nature dates back to many centuries. Dr. Roger S. Ulrich (Professor of Architecture at the Center for Healthcare Building Research at Chalmers University of Technology in Sweden) summarises the impact of nature on diseases and hospitalised patients.5 The research done by Dr. Ulrich in his journal article ‘View through a window may influence recovery’ provides scientific evidence that has proved that access to nature and green spaces has improved the health outcomes and wellbeing of patients within the hospitals.6

Marcus C. Cooper & Marni Barnes have discovered that residents of aged care and nursing homes who were in proximity to plants responded positively to their treatment.7 Marcus C. Cooper and Naomi Sachs present noteworthy literature in their book, ‘Therapeutic Landscapes: An evidence-based approach to designing Healing Gardens and restorative outdoor spaces’ the role of horticulture therapy, medicinal plants, and therapeutic healing gardens. According to Marcus C. Cooper, ‘The healing garden is both a process and a place. It is a concept at the meeting point of medicine and design’.8

Healing gardens for Children: An Essential space for Health

An issue published by the American Society of Landscape Architects in 1995 highlights that out of six healing gardens, only one was designed for children. This study contributes to the misconceived notion about healing gardens that children’s healing gardens aren’t as successful and do not demonstrate positive effects as proposed in theory. However, contemporary literature in the book ‘Children’s Hospice Gardens’ by Elizabeth Read, establishes with evidence that healing gardens immensely impact children and younger patients in a children’s hospital. It is observed that children who have access to healing gardens show a decrease in cortisol levels, quicker recovery, positive social behaviour, and possess active movements.9

Healing gardens are required for children to experience nature as restorative and recreational spaces.10 Samira Pasha in her article ‘Research Note: Physical Activity in Paediatric Healing Gardens’ elaborates that healing gardens for adults and the elderly predominantly cater to spaces that can offer maximum relaxation, comfort and recollection. Children’s healing gardens comprise more playscapes, interactive elements and a different anthropometric altogether.11

The literature by Sandra A. Sherman (affiliated with the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center) summarises that children’s anxieties and imagination can be studied through their behaviour at a themed playscape or via fantasy play. Her article ‘Post-occupancy Evaluation of Healing Gardens in a Paediatric Cancer Centre’, describes how healing gardens in pediatric hospitals have been designed to engage children with exercises and playful equipment that makes hospital visits memorial for them.12

The possibility to ‘play’ within a stressful environment of a hospital or medical institution differentiates a children’s healing garden from other traditional healing gardens. Healing gardens for children facilitate expression and exploration which is vital for their cerebral development particularly in daunting hospital environments and operational wards. Hence proving the argument, that healing gardens provide a wide range of restorative benefits.

Healing gardens for children are spaces where their personalities are meant to participate in the physical world, where recovering children can discover a sense of solace, and response to stimuli. British child psychiatrist and pediatrician Donald Winnicott emphasises that through play, a child can navigate its inner turmoil, fears, and express its desires.13 This notion reinforces my argument that a playful landscape has the potential to perform as a therapeutic space for children, their families, and hospital employees.

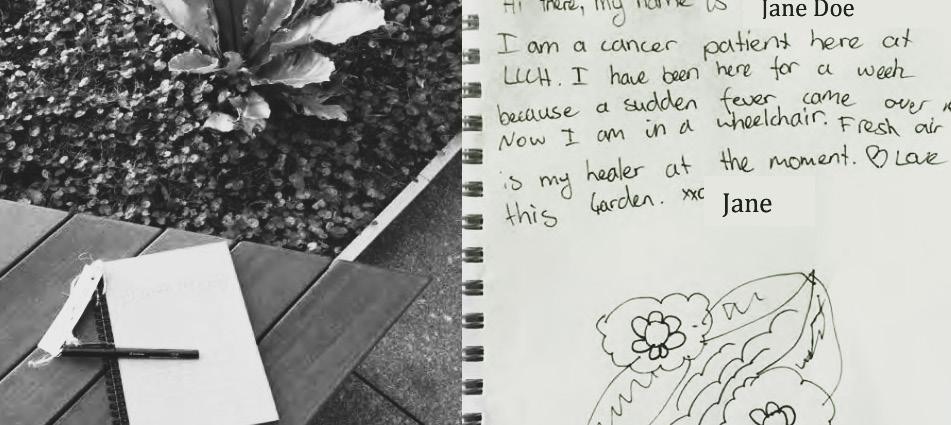

Figure 6: Survey via Bench Diary Records of a cancer patientMarcus C. Cooper emphasises that play therapy, horticultural therapy, wildlife therapy, and nature as therapy are some of the restorative therapies that add value to the healing garden. Through playscapes at the healing gardens, children can reframe hospitalisation as a pleasant experience rather than a painful one, giving them a sense of comfort and control in an unfamiliar environment.14 Since children associate reality through fantasy play, play is a form of action adopted by the child to initiate relationships, and engage with their surroundings. Healing Gardens provide these children with a wide scale of sensory action, activating their responses to stimuli.15

A significant strategy associated with play therapy is to allow children to have a sense of control within the healing garden. Healing gardens have a positive impact on children when they are exposed to situations where the child can control their environment and thus seek restoration from their stressful medical treatments.16 This strategy in landscape planning is extremely important as healing gardens are the only spaces within the medical institutions that provide this kind of freedom for the children, as against to the dreadful hospital wards where they have no control over things that are done to them.

Conclusion

Healing gardens is a rather contemporary concept within the field of medical research. Healing Gardens are the spaces that distract the children, and restore their innocence. Thus, after being surrounded by healing gardens within hospitals, children feel significantly positive and recover/ regain the health that has been impacted due to their illness, or medical condition.17 Therefore, healing gardens are essential spaces that should be considered for children as well. In conclusion, the Healing Gardens at the Lady Cilento Children’s Hospital are regarded as successful due to their generous scale, varied landscaped spaces, recreation activities, and strategic planning. The Bench Diaries and surveys are useful in identifying the different activities taking place in the gardens, and understanding how children are responding to their treatments.

Although there is a limited research available on the design considerations and requirements for healing gardens, insights into the Lady Cilento Children Hospital can aid the architects and medical practitioners on how to design impact worthy healing gardens. An extensive survey on horticulture therapy and planting strategies can help in understanding the spatial setting of a healing garden. Therefore landscape architects have to recognise that their role in designing the healing gardens directly impacts the recovery of children. It is crucial to acknowledge such kind of positive environments for children, not just within medical hospitals, but also around our immediate surroundings.

Word count- 2599 words

1. Beatriz Colomina & Mark Wigley, 2016, Are We Human? Notes on the Archaeology of Design (Zurich:Lars Müller Publishers).

2. Jenny Donovan, 2013, Designing to heal (Collingwood, Vic: CSIRO Publication).

3. ‘Children’s Health Queensland,’ 2022, Queensland Government, <https://www.childrens.health.qld.gov.au/going-to-hospital>.

4. A. Reeve, K. Walker-Nieberler & C. Desha, 2017, ‘Healing gardens in children’s hospitals: Reflections on benefits, preferences and design from visitors’ books’, Urban forestry & urban greening 26, 48–56.

5. Roger S. Ulrich, 1981, ‘Natural Versus Urban Scenes: Some Psychophysiological Effects’, Environment and Behaviour 13 (5), 523-553.

6. Roger S. Ulrich, 1984, ‘View through a window may influence recovery,’ Science 224 (4647), 420–421.

7. Marcus C. Cooper & Marni Barnes, 1999, Healing gardens : Therapeutic benefits and design recommendations (New York: John Wiley & Sons).

8. Marcus C. Cooper & Naomi Sachs, 2013, Therapeutic landscapes : an evidence-based approach to designing healing gardens and restorative outdoor spaces (Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons).

9. Elizabeth Read, 2019, Children’s Hospice Gardens: Using Nature to Enhance Well-Being (Llangibby, UK: Elizabeth Read).

10. Marcus C. Cooper & T. Hartig, 2006, ‘Essay: Healing gardens—places for nature in health care’, The Lancet (British edition) 368(1), S36–37.

11. Samira Pasha and Mardelle M. Shepley, 2013, ‘Research Note: Physical Activity in Paediatric Healing Gardens’, Landscape and Urban Planning 118, 53–58.

12. Sandra A. Sherman, James W. Varni, Roger S. Ulrich & Vanessa L. Malcarne, 2005, ‘Post-occupancy Evaluation of Healing Gardens in a Paediatric Cancer Centre’, Landscape and Urban Planning 73(2), 167–183.

13. Marcus C. Cooper & Marni Barnes, 1995, Gardens in Healthcare Facilities: Uses, Therapeutic Benefits, and Design Recommendations (Concord, CA, USA: The Centre for Health Design, Inc.).

14. Marcus C. Cooper, 2016, ‘The Future of Healing Gardens’, HERD 9(2), 172–174.

15. Roger S. Ulrich, 1991, ‘Stress recovery during exposure to natural and urban environments’, Journal of Environmental Psychology 11, 210-230.

16. Catherine Ward Thompson, 2011, ‘Linking Landscape and Health: The Recurring Theme’, Landscape and Urban Planning 99 (3), 187–195.

17. Marcus C. Cooper, 2001, ‘Hospital Oasis’, Landscape Architecture 91(10), 36-39.

Bibliography

1. Colomina, B., W. M. 2016. Are we human? Notes on an archaeology of design. Zürich:Lars Mülller Publishers.

2. Cooper, M. 2001. ‘Hospital Oasis.’ Landscape Architecture 91(10): 36-39.

3. Cooper, M. 2016. ‘The Future of Healing Gardens.’ HERD 9(2): 172-174.

4. Cooper, M., B. M. 1999. Healing gardens: therapeutic benefits and design recommendations. New York: John Wiley & Sons.

5. Cooper, M., M. B. 1995. Gardens in Healthcare Facilities: Uses, Therapeutic Benefits, and Design Recommendations. Concord, CA, USA: The Center for Health Design.

6. Cooper, M., S. N. 2013. Therapeutic landscapes : an evidence-based approach to designing healing gardens and restorative outdoor spaces. Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons.

7. Cooper, M. H. T. 2006. ‘Essay: Healing gardens—places for nature in health care.’ The Lancet (British edition) 368(1): S36–7.

8. Donovan, J. 2013. Designing to heal. Collingwood, Vic: CSIRO Pub.

9. Pasha, S., Shepley, M.M. 2013. ‘Research Note: Physical Activity in Pediatric Healing Gardens.’ Landscape and Urban Planning 118: 53-58.

10. Read, E. 2019. Children’s Hospice Gardens: Using Nature to Enhance Well-Being. UK: Llangibby.

11. Reeve, A., K. N.-W. C. D. 2017. ‘Healing gardens in children’s hospitals: Reflections on benefits, preferences and design from visitors’ books.’ Urban forestry & urban greening 26: 48–56.

12. Sherman S., J. W. V., R. S. U., V. L. M. 2005. ‘Post-occupancy Evaluation of Healing Gardens in a Pediatric Cancer Center.’ Landscape and Urban Planning 73(2): 167–183.

13. Thompson, C. W. 2011. ‘Linking Landscape and Health: The Recurring Theme.’ Landscape and Urban Planning 99(3): 187–195.

14. Ulrich, R.S. 1981. ‘Natural Versus Urban Scenes: Some Psychophysiological Effects.’ Environment and Behavior 13(5): 523-553.

15. Ulrich, R.S. 1991. ‘Stress recovery during exposure to natural and urban environments.’ Journal of environmental psychology 11: 210-230.

16. Ulrich, R.S. 1984. ‘View through a window may influence recovery.’ Science 224(4647): 420–421.

17. ‘Children’s Health Queensland.’2022. Queensland Government. <https://www.childrens.health.qld.gov.au/going-to-hospital>

07

Figure 1: Christopher Frederick Jones, 2024, ‘Lady Cilento Children’s Hospital landscapes’, https://architectureau.com/articles/lady-cilento-landscapes/, accessed 23rd April 20024

Figure 2: Christopher Frederick Jones, 2024, ‘Lady Cilento Children’s Hospital landscapes’, https://architectureau.com/articles/lady-cilento-landscapes/, accessed 23rd April 20024

Figure 3: A. Reeve, K. Walker-Nieberler & C. Desha, 2017, ‘Healing gardens in children’s hospitals: Reflections on benefits, preferences and design from visitors’ books’, Urban forestry & urban greening 26, 48–56.

Figure 4: Christopher Frederick Jones, 2024, ‘Lady Cilento Children’s Hospital landscapes’, https://architectureau.com/articles/lady-cilento-landscapes/, accessed 23rd April 20024

Figure 5: Christopher Frederick Jones, 2024, ‘Lady Cilento Children’s Hospital landscapes’, https://architectureau.com/articles/lady-cilento-landscapes/, accessed 23rd April 20024

Figure 6: A. Reeve, K. Walker-Nieberler & C. Desha, 2017, ‘Healing gardens in children’s hospitals: Reflections on benefits, preferences and design from visitors’ books’, Urban forestry & urban greening 26, 48–56.

Word count of Article_______2598 Word count of Summary_____99 words

Checklist

• Adhered to the word limit in the summary and the article.

• Inserted the main quote by C+W on the inside of the front cover.

• Followed the 5-sentence template in writing of the summary.

• Inserted word count of the summary.

• Inserted word count of the article.

• Adhered to the prescribed number of spreads.

• Adhered to the prescribed number of images.

• Researched and cited the required number of sources.

• Uploaded PDF file on issuu.com and provided active link on the from cover.

• Inserted the checklist on the back cover.

• Uploaded final PDF file on MyUni and Box.

• Uploaded final Black+Blue word file on MyUni and Box. (N/A)