14 minute read

Craymer’s Counsel | Robert Craymer B1 Insights | National Agricultural Aviation Association B4 Regina’s Perspective | Regina Farmer B6 Low and Slow | Mabry I. Anderson B14 20 Years Ago | Thrash Aviation meets community PR challenge B34 Wing and a Prayer | Carlin Lawrence

CRAYMER’S COUNSEL

Robert Craymer - robertc@covingtonaircraft.com

Wash Your Engine

Please wash your hands. Our parents made this request when we were young children. We are also hearing and seeing signs about washing our hands in our current situation—something so simple but can have a profound effect. Washing can work wonders.

When we talk about washing your engine, it has that same positive result. A clean engine is a happy engine. Pratt & Whitney Canada gives us insight into the maintenance manual on types of engine washes, guidelines for washing, and why they are essential. The item the maintenance manual does not explicitly tell us is when to wash. My question for you is, when do you wash your PT6 engine?

Time to discuss the types of engine washes that you should be doing and my thoughts on how often you might do each type. If you have sat through an engine discussion, washing almost always comes up as a topic of conversation. The maintenance manual defines three internal types of washes: Desalinization, Power Recovery and Turbine. I also remind folks not to neglect the external engine wash. Not only does it give you a chance to look your engine over, but it also provides an opportunity to make sure you have cables and components lubricated. Not cleaning these components and caring for their proper lubrication can lead to premature wear and failure. You want to be looking for early signs of corrosion as well. The earlier you catch corrosion, the better.

All internal engine washes are performed while motoring the engine. This provides two additional things to watch; first, make sure not to overheat your starter/generator, allow for a proper cool down in between cycles of motoring. The second concern is the potential to siphon the oil from the oil tank and flood the accessory gearbox. This is much more prominent in large PT6 engines. An indicator that shows up is oil coming out of the inlet case. When washing a large PT6 engine, we try and do as few motoring runs as possible. Begin your internal washes by engaging your starter. When the Ng is between 10% to 25%, water or cleaning fluid is injected into the engine at 2 to 3 gal/minute. Make sure and read your maintenance manual to see the complete washing instructions. All internal engine washes are performed while the engine is turning. Let’s define the washes now to make the best choice as to what type of wash you need.

The first internal wash is the desalinization wash. This wash is performed to remove salts, deposits and light dirt. This wash is performed with drinking quality water, provided minimum standards are met. I suggest to people who live in areas with a high mineral content in the water to use demineralized water. Desalinization wash can be a daily or weekly wash dependent upon the atmosphere you fly in. We talk about salt air, pollution, dust, and sand, but what about products being delivered with ag aircraft that are corrosive? Can these materials make it through the air filtration? My suggestion is to check the cleanliness of your compressor during your 100-hour inspection. This will let you know if you need to increase the frequency of your desalinization (plain water) washes. If you are doing a lot of fertilizer, make sure and run some water through your engine. We have seen some of the chemicals cause significant corrosion quickly on and in the engine when not taken care of. ➤

The second internal wash is the performance recovery wash. Pratt & Whitney Canada recommends this level of washing if there is a noticeable difference in engine performance. I would add that if you are doing regular desalinization washes and the compressor is still showing signs of dirt/salt/chemicals; then you should add a performance recovery wash to your regular schedule. This wash is like the desalination wash with the addition of a cleaning solution. Important note: ONLY use approved chemicals in the cleaning solution. There are several options available, and they are listed in the engine maintenance manual along with the proper mix ratios.

The final internal wash is the compressor turbine desalinization wash. This wash sprays clean water directly on the compressor turbine blades. A tool is required to perform the compressor turbine desalinization wash. A water rinse of the turbine is recommended when doing a performance recovery wash as the final step. This wash is used to remove residue from the CT blades and limit the opportunity for sulphidation to attack blade coating and or parent material. If you notice dirt or other things “sticking” to your compressor turbine (CT) blades, you need to perform this wash. The blades are being inspected at each nozzle interval via borescope, so you will be keeping an eye on how they are doing. If anyone has had to replace CT blades, you know just how valuable this small amount of preventative maintenance can be.

I encourage everyone to do washes based upon what you are seeing in and on your engine. Make sure you reference the manual for all the proper steps. Make sure all the drains are open and draining. Ensure to disconnect the air system going to the fuel control from the engine. Cleanliness can make a world of difference not only to the performance of your engine but also provide an opportunity to save you money as a preventative step.

Everyone wash your hands, wash your engine, stay safe, and let’s have a great season!

Please reach out to me at robertc@ covingtonaircraft.com if you have any questions, and I’ll be glad to assist.

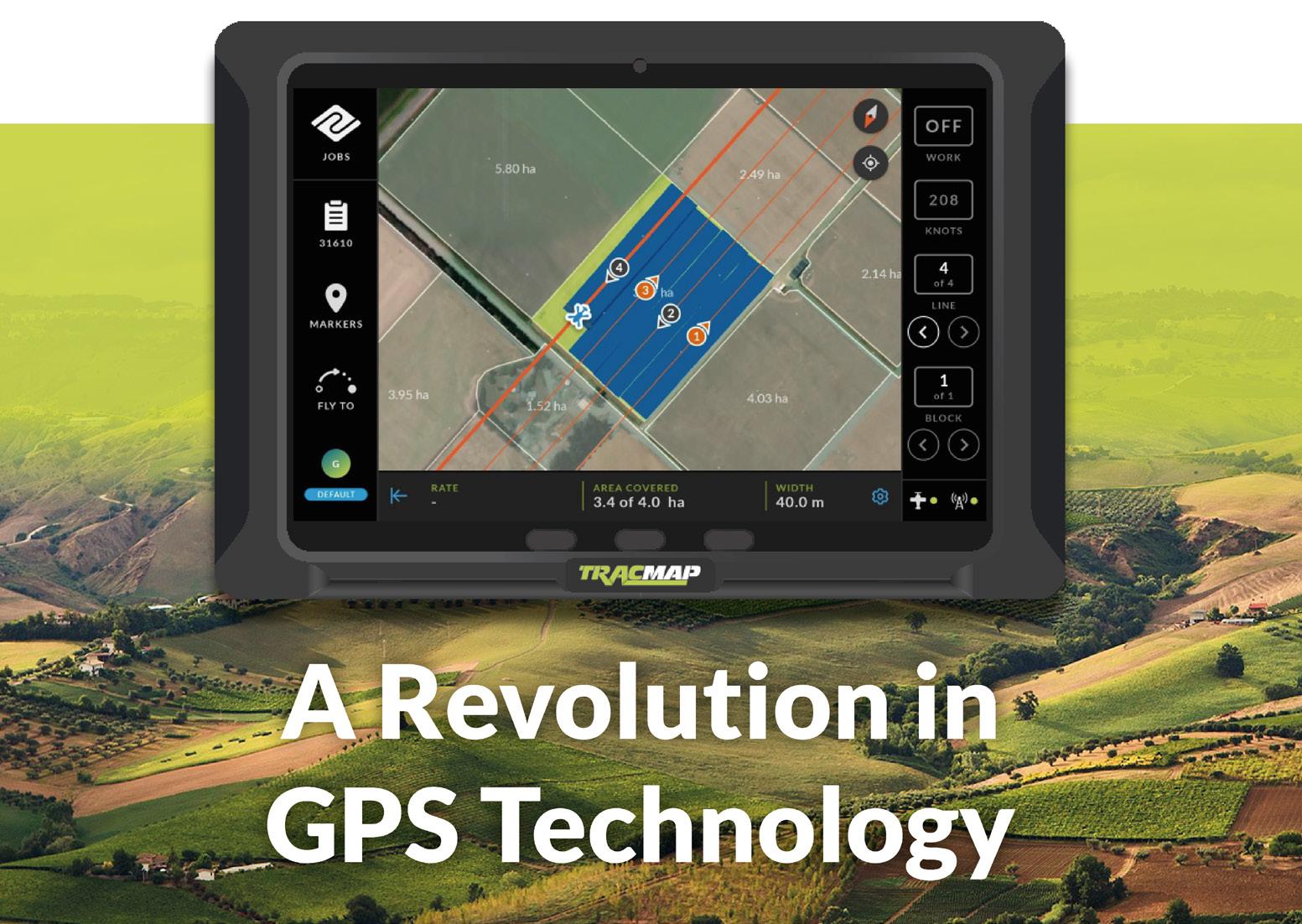

“TracMap’s flawless system helps pilots get as close to perfection as a farmer could ever want”

– Justin Watson, HeliTribe

Real time coverage sharing

Lightbar hazard warnings

Sync all settings with Pilot Profiles

Satellite and Topo maps

Fully operate device from the stick

Make contact today for limited time launch pricing

Bill Thomas Ben Duncan Support

Paraclete Aviation Life Support Announces International Expansions and North American Agreement in Wireless Communications for Helmets

Paraclete Aviation Life Support further strengthens its global presence in the rotor and fixed-wing helmet market, extending the company’s international footprint with the recent expansions into South Korea, Brazil and Australia, as well as its continued relationships in Europe, South America and Asia.

Paraclete is emerging as a global provider of aviation helmets building strategic partnerships in 28 countries throughout the world in commercial and military markets throughout 49 of the U.S. states since its launch in 2014.

Paraclete has secured certifications for its entire product line of Type 1 and 2 helmet models: the Aegis [ee-jis] D Type 1, the Aspida-D [a-speed-a], and most recently, the Aspida Carbon-D, as set forth by the U.S. Department of Interior [DOI] /U.S. Forestry Services [USFS] civilian helmet aviation standard. Paraclete is the only manufacturer to offer DOI-certified helmets in every size, S-XXL. Paraclete is committed to the safety and protection through our continuous innovations through evidence-based research science and technology.

Paraclete’s increasing presence into new markets with new distributors and partners [end users], continues to broaden its services into diverse markets with respect to air ambulance/HEMS, law enforcement, and federal agencies, as well as expanding its distributor relationships throughout the world. The company also announces its entryway to the global aviation communications market with the recent North American agreement with the wireless communications solutions manufacturer, GlobalSys, based in France. GlobalSys is a wireless voice communication solution featuring audio clarity, noise reduction, sound quality, with the mobility and adaptability of reconfiguration options for civilian and military aviation.

“As a primary driver in most businesses today, innovation must be qualified to confirm its overall value and efficiency,” said Paraclete CEO and Founder Scott Hedges. “While we continue to enhance the value of our helmet product line, we look for those relationships that support our core tenets - comfort, innovation and safety. We found that value with GlobalSys and the expanding wireless communications technology delivering an asset that crews need to ensure efficient operations.” GlobalSys CEO Dominique Retali, said, “We design our wireless solutions with adaptability and flexibility in mind. Our systems have the highest sound quality, which is of great importance for all operators. The advanced technology with our mobile unit Airlink 3085 provides the option to reconfigure to adapt to multiple aircraft and mission types in less than five minutes. The on- board network blocks out noise to ensure clear communications and without the wires obstructing movement in the aircraft, whether in the pilot’s seat or conducting a rescue mission 50 feet below the aircraft.”

“Mission work is all about teamwork, and effective communication is essential,” said Anthony Economos, Paraclete’s Vice President. “GlobalSys allows crews to replace the traditional hard-wired helicopter intercom with a wireless communications onboard network that provides a lifesaving service that links our helmets out to 300 meters simultaneously. Our entire mission is designing aviation helmets based on our three pillars without sacrificing safety and comfort. We also know that ‘comfort’ can be subjective, but we’ve also advanced our designs with innovative technology, which is experiential the first time a pilot dons one of our helmets.”

Paraclete is an ISO 9001:2015 certified manufacturer providing design, development, and manufacture of Aviation Life Support Equipment [ALSE], as well as education and training services. For more information about Paraclete products and training, contact www.paracleteaviationlifesupport.com | 931.274.7947 | sales@paracletelifesupport.com | 1792 Alpine Dr. Clarksville, TN 37040.

Decisions, Decisions, Decisions

By Ted Delanghe

Another ‘trick of the trade’ when faced with critical decision-making is to imagine six months in the future. What would people remember of the day when you decided to cease flying operations instead of continuing in marginal conditions with a resultant accident, incident, or non-effective application.

You’ve just returned from finishing a load on what you thought was your last flight of the morning. The temperature is rising, the winds are coming up, and you’ve already treated 3,000 acres. You reach the loading area and are just about to shut down when the mixer/loader hands you a last-minute worksheet. It’s got “high priority” stamped all over as it’s a canola crop being decimated by Bertha armyworms.

You take a quick look at the worksheet. Just one load with a short ferry. Decision time! While both winds and temps are coming up, they are still within limits, so you give the signal to load.

You tap the GPS coordinates into your nav program and look at the farmer’s map attached to the worksheet—big red barn in the northeast corner, stone piles in the south end. No obstacles indicated, so there shouldn’t be any issues.

Load is completed, and off you go, climbing to 500 feet AGL enroute. You notice in the climb it’s getting bumpy, starting at 300 feet. Probably wind shear. A couple of miles to go, and you see the big red barn and the stone miles. Good to go!

But wait! At the north end, you see the large towers of a 230 kV power line running through the field. Big surprise as it wasn’t on the farmer’s map! A decision has to be made to go over or under. If over, you’ll have to contend with wind shear on pullup to clear the towers, as well as having to run quite a few trim runs parallel to and on both sides of the line. If under, the line is sagging a bit with the increased temperature and bears a close look to ensure it is safe to do so. Decision time again! After a close inspection, you decide the best option is to go under.

One last review of the farmer’s map, and you notice a susceptible field marked to the east. With the westerly flow that makes it downwind. Is it far enough away to ensure no drift issues? Winds are still within limits, but you decide to leave a sizeable buffer zone just to make sure. One last decision: racetrack or back-to-back? If the powerline weren’t there, racetrack would be best, but the powerline is there. You decide that back-to-back would be the better option and give the field one last survey while setting up the first swath. Beyond the power line at the north end is a paved road, so you’ll have to keep an eye out for traffic. Another decision to make; it shouldn’t be a problem.

That’s when you note you will be flying into the sun towards the powerline. Is glare going to be a factor? One quick test run, and you decide it won’t be a problem. Decision: it’s a go! You run your first pass and, in due time, complete the application safely and effectively.

That scenario is typical of day-to-day ag operations, where sometimes it seems as if your helmet is on fire with decision after decision to make. Considering the serious consequences of making a bad decision – something which we’ve all done and hopefully have gotten away with – a review of the many factors that can contribute to good decision making is always a fruitful topic.

I have been very fortunate in my early career as an ag pilot to have met several individuals who were not only highly experienced but were willing to share that knowledge with the greenhorn that I was. A seasoned Kiwi ag pilot told me that good decision-making starts the moment you wake up and begin preparing for the day’s flights. Your attitude should be shifted into “Safety First” mode, which should form the cornerstone of all the decisions you will have to make that day.

When deciding whether a trip is a go or nogo, you need to answer two questions: will it be safe, and will it be effective. If the answer to both is not an immediate “Yes!” instead of a lot of humming and hawing, the trip should be left until you get that resounding “Yes!” answer. ➤

When things are going smoothly, the workload light, and there isn’t a pressing need to complete a trip, it’s easy to make good decisions, one of which is saying “No, this trip can wait!” when conditions so dictate. But once you get into a scenario where distressed farmers are lined up at the office because a sudden infestation of pests is destroying their crop, the weather limits are marginal, and you’ve already flown 23 trips (or was that 24 or 25) and fatigue is beginning to creep in, it’s a lot harder to make the correct decision to say “No.”

This is especially true when you are new to the business and feel the onus is on you to get the job done, even if it means pressing the many factors that go into making treatments safe and effective.

An interesting approach I’ve used to assist in the correct decision-making process started when my friend and I were working together off the same strip. We both carried a box of Cigarillos, even though neither of us was a smoker. Whenever it looked like conditions were getting to where a “Go/No Go” decision had to be made, one or the other would say over the radios, “time for a smoke.” We would both shut down and get together to discuss things rather than continue until it was really obvious operations needed to cease.

In most cases, just taking that little break was enough to put things in the right perspective and make the decision to stop flying until conditions improved. Whether it’s a smoke break, coffee break, or water break, make sure taking a break is SOP for your operation.

Another ‘trick of the trade’ when faced with critical decisionmaking is to imagine six months in the future. What would people remember of the day when you decided to cease flying operations instead of continuing in marginal conditions with a resultant accident, incident, or non-effective application. As with many things, when you’re right, no one remembers, but when you’re wrong, no one forgets.

NOTE: FAA’s “Aeronautical Decision Making” and Transport Canada’s “Human Factors for Aviation – Basic Handbook” are both excellent resources for learning more about the decision-making process specific to aviation.