BIRDCONSERVATION

The Magazine of American Bird Conservancy

ABC is dedicated to conserving wild birds and their habitats throughout the Americas. With an emphasis on achieving results and working in partnership, we take on the greatest threats facing birds today, innovating and building on rapid advancements in science to halt extinctions, protect habitats, eliminate threats, and build capacity for bird conservation.

abcbirds.org

A copy of the current financial statement and registration filed by the organization may be obtained by contacting: ABC, P.O. Box 249, The Plains, VA 20198. 540-253-5780, or by contacting the following state agencies:

Florida: Division of Consumer Services, toll-free number within the state: 800-435-7352.

Maryland: For the cost of copies and postage: Office of the Secretary of State, Statehouse, Annapolis, MD 21401.

New Jersey: Attorney General, State of New Jersey: 201-504-6259.

New York: Office of the Attorney General, Department of Law, Charities Bureau, 120 Broadway, New York, NY 10271.

Pennsylvania: Department of State, toll-free number within the state: 800-732-0999.

Virginia: State Division of Consumer Affairs, Dept. of Agriculture and Consumer Services, P.O. Box 1163, Richmond, VA 23209.

West Virginia: Secretary of State, State Capitol, Charleston, WV 25305.

Registration does not imply endorsement, approval, or recommendation by any state.

BirdConservationis the member magazine of ABC and is published three times yearly

Managing Editor: Matt Mendenhall

Graphic Design: Maria de Lourdes Muñoz

VP of Communications & Marketing: Clare Nielsen

Contributors: Erin Chen, Jennifer Davis, Annie Hawkinson, Bennett Hennessey, Hardy Kern, Lara Long, Jack Morrison, Michael J. Parr, Steve Roels, Jordan Rutter, Rebekah Rylander, Amy Upgren, George Wallace, Kelly Wood

For more information contact: American Bird Conservancy P.O. Box 249

The Plains, VA 20198

540-253-5780 • info@abcbirds.org

Find

ABC

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Spring 2024

FEATURES

Return of the Millerbird

Decades of research, planning, and action by ABC and partners led to a big win for this little-known Hawaiian songbird. p. 18

Search On!

Just over two years since the Search for Lost Birds began, the initiative has rediscovered species, formed partnerships for conservation and research, and renewed interest in the world’s most elusive birds. p. 28

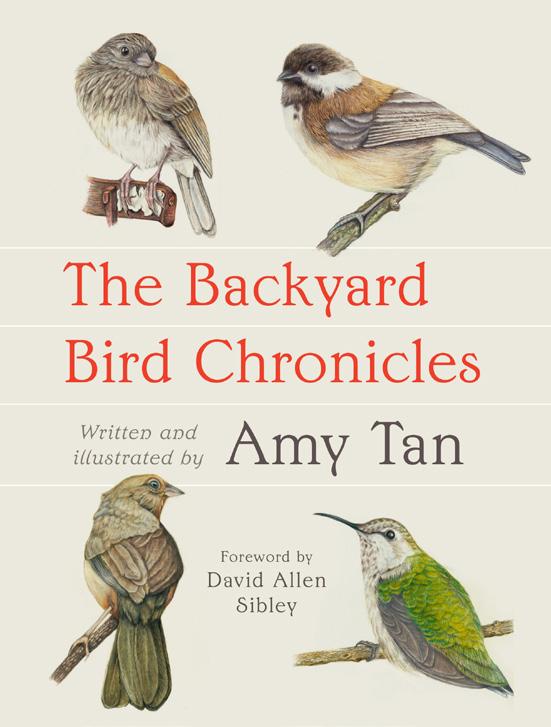

Amy Tan’s Bird Chronicles

A sneak peek at the celebrated author's new book about birds. p. 34

DEPARTMENTS

BIRD’S EYE VIEW

Kicking off our 30th anniversary year! p. 4

ON THE WIRE p. 8

BIRDS IN BRIEF p. 16

ABC BIRDING

Serra Bonita Reserve, Brazil p. 39

BIRD HERO

Meet the leader of conservation efforts for the stunning Araripe Manakin. p. 42

Celebrating ABC’s 30 Years of Successes for Birds

by Michael J. ParrHere at American Bird Conservancy, we’re celebrating our 30th anniversary! Milestones like this one are a wonderful opportunity to share highlights of our work over the last three decades — and celebrate the people who have had a hand in our success.

ABC specializes in conserving wild birds and their habitats throughout the Americas, and to date this has included providing habitat for more than 3,000 bird species — around 30 percent of the world’s total — that have been recorded at sites conserved by ABC and our partners.

I have worked for bird conservation at ABC since 1996, and I believe that ABC’s steady focus on our mission — conserving wild birds and their habitats throughout the Americas — and our focus on delivering results, has helped ensure that the funds we receive are used to really make a positive difference for birds and their habitats on the ground. Dedicated supporters, an expert staff, a strong and diverse network of partners, and an independent, experienced Board of Directors have provided us with a powerful formula for success.

I’m also incredibly proud of how this organization operates with integrity and respect, even in the face of tough situations, and how we welcome everyone who wants to make a difference for birds. Focusing on ends is important, but only if you are also reaching these ends by fair, equitable, and inclusive means.

I extend a special thank you to ABC’s dedicated staff and Board members, who play a critical role in our success. And of course, all of us at ABC are grateful to our members and supporters for their generous financial support over the last three decades. By believing in and backing ABC’s mission and approach, you have made our results for birds possible. Thank you!

‘I’m incredibly proud of how this organization operates with integrity and respect, even in the face of tough situations, and how we welcome everyone who wants to make a difference for birds.’

Results for Birds and Their Habitats

Our 30th anniversary is a great occasion to take a look at how we have delivered on our mission. I’ve summarized a selection of ABC’s highest-impact accomplishments here, and as a supporter, I hope you will also feel proud in what we’ve accomplished collectively, working with hundreds of partners.

• Establishing and building a 1.1 million-acre network of 100-plus protected areas in 15 countries. The Latin American Reserve Network — supported by ABC and managed by 59 on-theground partners — provides protected habitat for more than 80 of the most endangered birds in the Americas, including the Antioquia Brushfinch, Blue-throated Macaw, and Short-crested Coquette. Many migratory birds, including thrushes and warblers, also use the habitat in these protected areas. In addition to providing vital habitat for birds, these and many other ABC conservation efforts support the well-being of local communities and make an important contribution to combating climate change by keeping carbon on the landscape.

• Planting more than 7.7 million trees in bird reserves and buffer areas in countries such as the Dominican Republic, Ecuador, and Peru — resulting in improved habitat for birds and a range of benefits to people, from carbon sequestration to water conservation.

• Taking bold action with partners to prevent the extinction of birds in Hawai‘i, including translocations of ‘Ua‘u (Hawaiian Petrel) and ‘A‘o (Newell’s Shearwater) to a predator-free enclosure at Kilauea National Wildlife Refuge, where they can safely breed; and the establishment of a thriving new population of Millerbirds on Laysan Island (see page 18). We are also playing a key role in the critically important Birds, Not Mosquitoes project to save the state’s 17 remaining honeycreeper species (see page 11). This multiagency partnership is dedicated to decreasing the incidence of deadly avian malaria by reducing populations of disease-carrying mosquitoes.

• Improving management of more than 9.3 million acres of habitat to reverse population declines of migratory birds, much of which was accomplished by working with Migratory Bird Joint Ventures — networks of partners including federal and state agencies, other nonprofit groups, tribes, and private landowners. ABC’s habitat work, increasingly focused in priority geographies called BirdScapes, is part of our response to the groundbreaking 2019 study (co-authored by ABC) showing that nearly 3 billion birds have been lost from U.S. and Canadian breeding populations since 1970. A few examples of species that are benefiting from ABC-led efforts to improve their

habitats are Kirtland’s, Cerulean, and Goldenwinged Warblers, Long-billed Curlew, Northern Bobwhite, Snowy Plover, and Western Meadowlark.

• Addressing the top human-caused threats to birds in habitats across the Americas. ABC programs have played a key role in passing bird-friendly building ordinances in 24 municipalities; in encouraging millions of cat owners to keep their cats indoors; in the cancellation or restriction of 15 different pesticides that are toxic to birds; and the halting or mitigation of wind-energy projects in at least 17 locations where risks to birds were unacceptably high — in keeping with our philosophy that renewable energy is essential in the fight against climate change, yet must be sited in areas where impacts on birds will be minimized.

I want to acknowledge my predecessor, founding President Dr. George H. Fenwick, who led ABC through its fledgling years and, along with Rita Fenwick, built the firm foundation the organization has today. Since 1994, we’ve grown from a handful of staff to more than 140; and our annual budget has increased from around $250,000 to $35 million. This incredible growth means more results for birds — with still bigger plans to come.

People Made It Possible

Many great people have contributed to ABC’s success. While listing them all is unfortunately not possible in this message, I do want to acknowledge a few individuals and groups who have made outsized contributions over these 30 years.

• Dedicated Staff: ABC would not be here today without the leadership and dedication of George and Rita Fenwick. I’m grateful to both of them for the strong foundation they built for ABC. Several other former ABC staff members contributed immensely to our long-term success, with tenure starting in our early years and continuing over 20 or more years: Jane Fitzgerald, Merrie Morrison, David Pashley, and George Wallace. I’m also grateful to the many staff who have been with us for 15-plus years (or will reach that milestone this year): Jenna Chenoweth, Chris Farmer, Todd Fearer, Jim Giocomo, Steve Holmer, Dan Lebbin, Jack Morrison, Gemma Radko, Chris Sheppard, Beth Wallace, David Wiedenfeld, and Dariusz Zdziekbowski. Thanks for your commitment to ABC!

The 10 Million Acre Challenge

Looking beyond 2024, ABC is implementing a largescale vision to conserve the next 10 million acres of bird habitat, which we’re calling “The 10 Million Acre Challenge.” Through this ambitious campaign, we will secure protected habitat for “gap” species — endangered birds whose ranges fall outside of any existing protected area in Latin America and the Caribbean, as well as improving habitat for many Neotropical migrants. In North America, we will prioritize healthy habitat for all bird species whose populations are in steep decline. As we’ve done since the beginning, ABC will use rigorous science to prioritize birds of highest concern — ensuring conservation of the most important habitats and sites to prevent extinctions and bring back populations of dwindling species. This challenge includes making habitat safe for birds by, for example, removing feral cats, wind turbines, and pesticides that may impact critical sites and landscapes.

Bird conservation is my life’s work, and I am extremely lucky and proud to have been given the chance to lead ABC. I’m excited about what the future holds and what this organization will achieve over the next 30 years. I believe that, by staying

• Board Leadership: ABC continues to be governed by a remarkable Board of Directors, and I’m grateful to all of them. Most of all, I’d like to acknowledge those who served as Board Chair, providing extraordinary leadership to the organization over the years: Howard Brokaw, Ken Berlin, Jim Brumm, Warren Cooke (the first to break the line of “B” surnames!), and our current Chair, Larry Selzer.

• Partners across the Americas: ABC works with hundreds of partners across the Americas to achieve results for birds. Each one has made a difference. Although space precludes a full listing here, I want to send my gratitude to all who work with us across the hemisphere. Please see our 2023 Impact Report for a full list of partners (link at right).

I want to especially acknowledge the strong, long-lasting partnerships built in Latin America and the Caribbean. These six groups have worked with us for more than 20 years, helping to prevent extinctions of some of the world’s rarest bird

focused on our mission and true to our principles — including welcoming diverse perspectives and honoring differences through our Together for Birds initiative — we will reach the ultimate milestone: a turning point where bird declines turn to increases, and where bird extinctions are a thing of the past. Working together, we can ensure that the future abounds with birds and nature. We can only accomplish this, however, by finding ways to be much more inclusive in terms of the people we engage in bird conservation, by ensuring expanded access, and by providing ways to engage people with birds and nature that have not existed before. I look forward to working with you to make this happen.

Sincerely,

Michael J. Parr, President American Bird Conservancy

Michael J. Parr, President American Bird Conservancy

species: Fundação Biodiversitas (Brazil), Asociación Ecosistemas Andinos – ECOAN (Peru), Fundación de Conservación Jocotoco (Ecuador), Fundación ProAves (Colombia), Asociación Armonía (Bolivia), and Sociedade para a Conservação das Aves do Brasil - SAVE Brasil (Brazil).

I'd also like to send gratitude to the Migratory Bird Joint Ventures (JVs) — cooperative, regional partnerships that work to conserve habitat for the benefit of birds, other wildlife, and people. We’ve partnered with JVs for more than 25 years and celebrate the millions of acres improved for birds across the U.S. and Mexico.

• Members and Supporters: And of course, people like you! Thousands of people have made ABC’s results possible, including nearly 30,000 ABC members who support our day-to-day operations. I’m grateful to each one of our members and donors for their sustained support. Please see our 2023 Impact Report for more about the people and organizations behind ABC’s remarkable success: abcbirds.org/annual-reports

Almost 22,000 Acres Protected for the Tiny Short-crested Coquette

One of the rarest and most spectacular hummingbirds in Mexico, found only in a small area of mountainous woodlands, is the focus of an ambitious conservation project that includes ABC, the Universidad Autónoma de Guerrero (Autonomous University of Guerrero), and local communities, as well as Mexico’s National Commission of Protected Natural Areas (Comisión Nacional de Áreas Naturales Protegidas, or CONANP).

Six protected areas, totaling nearly 22,000 acres in the southern state of Guerrero, are being established to help prevent the extinction of the tiny Short-crested Coquette. The Critically Endangered species has an estimated population of fewer than 1,000 adults.

Four of the protected areas were declared in 2023 — the first ever created for the species — and two more are expected to be created this year. Ranging in size from about 2,800 acres to nearly 5,000, the conservation reserves provide a network of preserved forest habitat. The properties are administered by

the ejidos (communally owned and farmed lands) and local communities and are included in Mexico’s Protected Areas Network coordinated by CONANP.

For about five years, ABC has been working on the coquette project with ecologist Roberto Carlos Almazán-Núñez, the coordinator of research and conservation for the bird at the Autonomous University of Guerrero.

The Short-crested is the northernmost of the 11 coquette species in the genus Lophornis, and it is by far the most endangered. The majority of sightings occur along a road dotted by villages in the Sierra de Atoyac, where the coquette inhabits an area of about 44 square miles between 2,300 and 4,900 feet elevation.

Habitat loss is the main driver behind the species’ decline. About one-fourth of its woodland habitat in the Sierra de Atoyac has been lost to agriculture and livestock uses; what remains is threatened by forest fires and climate change.

“We needed to take action to reduce threats to this hummingbird,” explained Almazán-Núñez. “To ensure greater success, we partnered with local communities, taught them to monitor wildlife, and involved them in government programs that provide financial support for the sustainability of the new protected areas. Currently, there is great interest from other communities where the coquette occurs to join efforts to protect their forests, which began with this project developed in coordination with ABC.”

Almazán-Núñez partners with local residents to help them manage the new protected areas. In addition to wildlife monitoring, community members work to prevent forest fires, place camera traps to watch the movements of wild cats and other mammals, manage native conifer trees, and complete other tasks.

“It is wonderful to see a small project, started by ABC to better understand the basic ecology of this Critically Endangered species, grow into a community-based conservation program,” said Amy Upgren, ABC’s Director of International Programs. “Each of the six communities voted to set aside part of their communal lands to create reserves for the coquette and other species, and they are now managing these reserves to ensure their continued conservation.”

Almazán-Núñez and Upgren will explain more about conservation of the coquette at a future ABC webinar. In addition, the university recently produced a 20-minute documentary about the bird and the Sierra de Atoyac. Scan the QR code below or visit bit.ly/coquette-doc to learn more.

ABC thanks Patricia Davidson, the Marshall-Reynolds Foundation, the Weeden Foundation, George Powell, the Estate of William Belton, the Estate of Mary Janvrin, Lawrence Thompson, and Dr. Janice D. Barry for their support of work on behalf of the coquette.

Flaco’s Death Reflects Familiar Threats to Raptors

Flaco, the famous Eurasian EagleOwl that captivated people nationwide during the year that he lived in and around New York’s Central Park, died in late February due to two all-too-common threats to birds: window collisions and poisoning.

Postmortem testing on his body revealed traumatic injuries from a window collision as well as two underlying conditions. “He had a severe pigeon herpesvirus from eating feral pigeons that had become part of his diet, and exposure to four different anticoagulant rodenticides that are commonly used for rat control in New York City,” the Central Park Zoo reported. “These factors would have been debilitating and ultimately fatal, even without a traumatic injury, and may have predisposed him to flying into or falling from the building.”

For over a year, Flaco had survived outside of the Central Park Zoo after his enclosure was vandalized and he got out.

Anticoagulant rodenticides work by thinning the blood and preventing coagulation. At low levels, a bird that has ingested rodenticide may appear sluggish, weak, and disoriented. Higher levels of exposure can cause bleeding and lead to shock and death in animals. The effects of rodenticide can linger in the body for months and compound over time as the animal ingests more poison. They can cause seizures, kidney failure, muscle weakness, and eventually, death.

“Flaco’s death tells a story all too familiar for raptors: habitat loss drives adaptation to urbanized areas, and urbanized areas attract rodents,

which people want to control with chemicals,” said Hardy Kern, ABC’s Director of Government Relations. “Flaco’s death is indicative of the unintended consequences of rampant overuse of these chemicals.”

The widespread use of pesticides (the umbrella term encompassing insecticides, rodenticides, and other related products), whether used to control mice or combat weeds, has profound and cascading effects. The consequences of these poisons can ripple out far beyond their intended targets. Rats and mice that have ingested rodenticides tend to move sluggishly, making them easy targets for birds of prey.

For a bird of Flaco’s size — the Eurasian Eagle-Owl is one of the world’s largest owl species, with a wingspan that can reach an impressive 6 feet — one poisoned rat may not have killed him, but the accumulation over time can be deadly. Pigeon herpesvirus, a virus carried by healthy feral pigeons, can be harmful to birds of prey, causing inflammation and damaging tissue.

“When four different anticoagulants are found in the same bird, we can't ask for a clearer need for action,” said Kern. “Sadly, this illustrates the impacts these chemicals have on native birds of prey like Redtailed Hawks and screech-owls. We need to reduce our dependence on anticoagulant rodenticides. Viable alternatives exist and numerous strategies are possible.”

Flaco’s toxicology testing also showed the presence of a substance that has been banned in the U.S. since the 1970s: DDE, a breakdown of the agricultural pesticide, DDT. DDT weakened the eggshells of birds like the Brown Pelican and Peregrine Falcon, leading to precipitous declines for some species that are still recovering today. The presence of this DDT breakdown product in Flaco’s blood decades later is a chilling reminder of the long-lasting effects of human actions on wildlife and the environment.

ABC thanks the Raines Family Fund and the Carroll Petrie Foundation for their support of our Pesticides program.

ON the WIRE

Red List Updates Include Hawaiian Birds

In late 2023, the International Union for Conservation of Nature announced reassessments of the threat categories for more than 200 of the world’s 11,000-plus bird species.

In the Western Hemisphere, where ABC’s work is focused, 80 species were downlisted to lower threat levels while six were uplisted. Two of the six are found only on the Hawaiian island of Kaua‘i: the ‘Anianiau and the Kaua‘i ‘Amakihi, both of which were moved from Vulnerable to Endangered. The two species suffered population declines exceeding 60 percent from 2008-2018, and the threat of avian malaria hangs over each of them. (ABC and several partners recently made significant progress in our yearslong project to reduce the mosquito-borne disease in hopes of restoring songbird populations in Hawai‘i; see page 11 for more.)

The other four uplisted species are:

• Magellanic Plover. This shorebird of southern Argentina and southern Chile was moved from

Reserve Established for Rare Antpitta

On the eastern slope of the Andes Mountains, southeast of Bogotá, Colombia, lies a newly established nature sanctuary: Reserva Natural Refugio Tororoi, a 446-acre (180.52-hectare) expanse of misty, highland cloud forest. The site, created through a partnership between ABC, Fundación Camaná Conservación y Territorio, the direct investment funds of the Conserva Aves initiative, and a family whose property borders the reserve, protects critical habitat for the

Near Threatened to Vulnerable. Recent surveys of large parts of the breeding and nonbreeding ranges suggest the population numbers only 330 adults.

• Citron-throated Toucan. This colorful species of forests in Colombia and Venezuela was uplisted from Least Concern to Near Threatened because habitat loss in its range appears to have accelerated since 2016.

• Red-faced Parrot. The assessment of this Andean parrot of southern Ecuador and northwestern Peru changed to Endangered. Recent field surveys suggest its population is rapidly declining due to habitat destruction and

Endangered Cundinamarca Antpitta, which numbers only 330 to 800 individuals.

The small olive-brown bird has a white throat and gray underparts marked by thin, white streaks. It was documented for the first time in 1989 by American birder Peter Kaestner, who is now an ABC Ambassador. While birding one day, he had heard an unfamiliar fuit foh feer call coming from the understory, recorded the sound, played it back, and waited. After about 45 minutes, out popped an antpitta that was unlike any antpitta Kaestner

fragmentation. The population is estimated at 1,200 to 1,600 adults.

• Juan Fernandez Tit-Tyrant. This bird occurs only on Robinson Crusoe Island west of Chile. The loss of native vegetation and introduced plants and animals have led to an ongoing decline for the bird, which now is estimated at 780 individuals. Its status was changed from Near Threatened to Endangered.

Of the 80 downlisted species, two are now Endangered; eight changed to Vulnerable; 22 moved to Near Threatened; and 48 shifted to Least Concern. Most of these reassessments occurred due to improved knowledge about the species or its habitat or because incorrect data had been used for previous assessments. One bird whose status genuinely improved thanks to conservation work, however, is the Millerbird of the Northwestern Hawaiian islands. ABC played a large role in its recovery; you can read the hopeful story of its downlisting — from Critically Endangered to Endangered — on page 18.

(or any other birder or ornithologist) had ever seen. A few years later, it was scientifically described and given the name Grallaria kaestneri. (This year, Kaestner made headlines when he became the first birder to tally 10,000 bird species on his life list.)

Today, the antpitta faces pressure from deforestation that could decimate the habitat of the rangerestricted species. “Much has changed in this area since the species was first documented in 1989, and the small range of habitat where Cundinamarca Antpittas

Mosquito Control Project Launched to Save Honeycreepers

Following years of rigorous study and analysis, a multi-agency partnership in Hawai‘i called Birds, Not Mosquitoes (BNM) began releasing non-biting male Southern House Mosquitoes on Maui and Kaua‘i in November 2023 after regulatory approval from state and federal agencies. The goal is to reduce invasive mosquito reproduction and cause the insect’s populations to decrease. When that happens, BNM believes, mosquito-borne avian malaria will become less of a threat to the state’s native honeycreepers.

The work is part of the U.S. Department of Interior’s Strategy to Prevent the Extinction of Hawaiian Forest Birds, and it is urgent: Hawai‘i’s forest birds have declined from more than 50 different native honeycreepers to just 17 species remaining today.

Mosquitoes are rapidly moving to higher elevations as the climate changes and native forests get warmer and drier. Without significantly reducing mosquito populations, multiple native bird species are likely to go extinct in the wild in less than

10 years, including the Kiwikiu and ‘Ākohekohe on Maui, and ‘Akikiki and ‘Akeke‘e on Kaua‘i.

“After decades without the tools to solve this problem, this project is our best chance to save the birds and native forests for future generations,” said Chris Farmer, Hawai‘i Program Director for ABC. “I am excited and honored to be part of this historic collaboration to address difficult, previously intractable conservation problems and commit to long-term solutions.”

The male Southern House Mosquitoes, which do not bite or transmit disease, carry a strain of the common, naturally occurring Wolbachia bacteria. When they mate with females in the wild, which carry a different strain of this bacteria, their eggs don’t hatch, causing mosquito numbers to decline.

Learn more at birdsnotmosquitoes.org.

ABC thanks the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, the BAND Foundation, John andBayardCobb,theAditiFundof theHawai‘iCommunityFoundation, theLemmonFoundation,andmany othersfortheirsupportofBirds,Not Mosquitoes.

are found is at risk of shrinking further,” said Eliana Fierro-Calderón, International Conservation Project Officer for ABC. “The Reserva Natural Refugio Tororoi provides a safe haven and hope for the future of this species, about which we still have so much to learn.”

The Reserva Natural Refugio Tororoi is the first protected area dedicated to the species. Besides the antpitta, it supports endemic birds like the Sickle-winged Guan and the Slaty Brushfinch and migratory species including the Blackburnian Warbler

and the Swainson’s Thrush.

With the reserve secured, a habitat management plan is being designed and implemented, and ABC is supporting prioritized activities in the plan, including trail improvement, signage installation, and infrastructure to welcome more visitors.

ABC and our partners acknowledge the Bezos Earth Fund, BirdLife International, and Bobolink Foundation for their support on this project.

Watch our February webinar with Kaestner, Fierro-Calderón, and others discussing the antpitta and the new reserve at abcbirds.org/ AntpittaWebinar

Record Reddish Egret Flock Found Near SpaceX Site

In mid-December 2023, biologists conducting a Christmas Bird Count near Brownsville, Texas, tallied 739 Reddish Egrets — the largest flock ever recorded for the species away from breeding colonies. The birds were foraging in shallow mudflats of the Lower Rio Grande Valley National Wildlife Refuge, which is near Boca Chica State Park on the Gulf of Mexico shoreline.

Justin LeClaire, an avian conservation biologist with Coastal Bend Bays & Estuaries Program, was among the observers and posted the sighting on eBird, the world‘s largest biodiversityrelated citizen science project. LeClaire had a similar but smaller sighting of more than 500 Reddish Egrets in the same area during the 2019 Christmas Bird Count.

LeClaire and his colleagues estimate that 17-20 percent of the Reddish Egret population in Texas and the bordering Mexican state Tamaulipas was present. Moreover, the flock represented up to 10 percent of the egret’s global population (7,000-10,000 individuals). The International Union for the Conservation of Nature classifies the bird as Near Threatened. In Texas,

it is listed as Threatened and as a Species of Greatest Conservation Need, whereas in Mexico it is listed as an Endangered species.

The mudflats where the flock was reported are not far from the SpaceX launchpad in Boca Chica, raising additional concerns about the company’s rocket launches. SpaceX activity permitted by the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) is the subject of a lawsuit that ABC and other organizations filed last year, alleging that the FAA failed to fully analyze and mitigate environmental harms inflicted by SpaceX on the region’s sensitive habitats. (Read more in our Fall 2023 issue, page 8.)

“There is no doubt the coastal habitats around Boca Chica area in both the U.S. and Mexico are critical for all kinds of birds — waterbirds, shorebirds, waterfowl, and upland birds — as well as other wildlife that use them year-round or during migration,” said Jesús Franco, Assistant Coordinator of the Rio Grande Joint Venture, a binational

migratory bird and habitat alliance that ABC supports. “Because of this, there is also no doubt that man-made disturbance in the area can have significant negative effects for those habitats and wildlife, particularly for a coastal habitat-obligate species like the Reddish Egret.”

Rebekah Rylander, Science Coordinator of the Rio Grande Joint Venture, added: “Reddish Egrets have a very unique foraging behavior, and they require tidal flats with certain water depths and water clarity to catch their prey. They don’t usually forage in deeper water, like Great Blue Herons and Great Egrets often do. Thus, they are highly dependent on these specific foraging grounds that are dwindling due to habitat conversion/degradation, anthropogenic disturbance (such as that caused by SpaceX), and sea-level rise, among other things. For the tidal flats at Boca Chica to support 700-plus Reddish Egrets at a time deems it an incredibly important area for this species for both the U.S. and Mexico.”

Making a New Home for Kirtland’s Warblers in Wisconsin

Atimber harvest that began last fall on a tract of land in central Wisconsin is one of the first steps in a long-term plan to create new habitat for the rare Kirtland’s Warbler.

The harvest of Red Pine is taking place on one-third of a 400-acre property in Adams County that The Nature Conservancy (TNC) acquired in 2022. Last summer, TNC staff began controlling invasive buckthorn, honeysuckle, and spotted knapweed on the land. This fall, a prescribed fire will replicate the effects of a natural fire by clearing the land and preparing the soil bed for the project’s next step: the planting of more than 100,000 Jack Pine seedlings in spring 2025. Grants to ABC from the federal Regional Conservation Partnership Program are supporting the work.

The Kirtland’s Warbler, which was removed from the endangered species list in 2019 after a decades-long recovery from a brush with extinction, continues to rely on the conservation work of state and federal agencies, nongovernmental organizations, and other partners. The species breeds primarily among stands of Jack Pine trees that are 6 to 20 years old, meaning that once the seedlings are in the ground, the waiting begins.

Steve Roels, the Director of ABC’s Kirtland’s Warbler program, said male warblers are expected to turn up five

All About Forests

years after the planting, and females likely would join them a year or two later to nest on the tract. If all goes well, that section of the property would remain reliable breeding habitat for the warblers until 2045, when the trees would be harvested and the process would begin again.

Meanwhile, the partners involved in the project, which is led by Hannah Butkiewicz, TNC’s Central Sands Project Manager, plan to implement the harvesting, prescribed fire, and Jack Pine planting process on the remaining two-thirds of the property over the next 10 to 20 years. The goal is to create a shifting mosaic of Kirtland’s Warbler habitat as well as pine and oak barrens on the property.

More than 95 percent of the warbler’s population breeds in Michigan, but in 2007, the species began nesting in Wisconsin and Ontario as well. Wisconsin’s current breeding population has about 40-60 birds, and Adams County hosts 30-40 of them. Roels noted that the species has “an uncanny ability to find habitat, which makes sense since the habitat is ephemeral. So we are confident that the birds will be able to find the new habitat when it is ready.

“Expanding the breeding range of Kirtland’s Warbler is a top goal for the Kirtland’s Warbler Conservation Team, where ABC plays a lead role,” Roels said. “Having birds breeding outside the core range in Michigan’s Lower Peninsula is a key insurance policy for a species that remains one of the rarest songbirds in North America.”

The decades-long work plan on behalf of the bird is invigorating, said Butkiewicz. “I’m happy to be part of it,” she said. “I’m really looking forward to watching things develop. This project will be an exciting part of my career.”

ABCthankstheWeedenFoundation, Persevere Fund, Harry A. and Margaret D. Towsley Foundation, and many others for their support of our Kirtland’s Warbler program.

F or the first few months of 2024, ABC’s blog is featuring special content about one of the most important habitats for birds: forests! (Later in the year, we’ll focus on other habitats.) Recent forest-focused stories include profiles of tropical and temperate forests, as well as a spotlight on the Swallow-tailed Kite of southeastern forests. Scan the QR code or visit abcbirds.org/blog to read these and other stories about forests!

Bring Habitat Back

Each spring, as they journey north, migratory birds search for safe places to rest, refuel, and ultimately build a nest. At each point in their migratory journey, and once they reach their breeding grounds, birds need healthy habitat best suited for them. Kirtland’s Warblers need Jack Pine trees, Hermit Thrushes need deciduous and coniferous forests, Bobolinks need damp meadows and natural prairies, Marbled Murrelets need old-growth forests, and Least Terns need sandy beaches. Wherever they go, and wherever they are, birds need healthy habitats to survive and thrive.

Over the past 30 years, thanks to dedicated members and supporters like you, American Bird Con-

in the Andes for birds such as Colombia's Critically Endangered Gorgeted Puffleg, restoring grasslands in the central region of the United States for birds like the Northern Bobwhite, cleaning up beaches for coastal birds like the Piping Plover, or preventing bird collisions with glass in big cities and your neighborhood, we’ve worked together to bring habitat back.

Your support is what makes it possible to deliver these significant conservation results.

There is no doubt that habitat loss is the greatest threat to birds, which is why ABC has set the challenge to protect and conserve the next 10 million acres for birds across the Americas. We can’t do this without your help.

Right now, thanks to a dedicated group of supporters, ABC has launched a special Bring Habitat Back 1:1 Match with a goal of raising $500,000 for bird conservation by June 30.

Please support us in this critical work with your gift to our Bring Habitat Back 1:1 Match Campaign.

Conserving birds is only possible if we are also able to conserve the habitat they need to survive. When we bring back habitat, we bring back birds.

Please respond with your most generous gift today. Thank you for your support for bird conservation.

Will you help us bring habitat back?

Please respond with a gift by June 30!

Use the enclosed envelope, scan the code, or abcbirds.org/BringBackHabitat

ABOVE: Northern Bobwhite by Walter Eastland, Shutterstock RIGHT: Hermit Thrush by Joshua Galicki

ABOVE: Northern Bobwhite by Walter Eastland, Shutterstock RIGHT: Hermit Thrush by Joshua Galicki

BIRDS in BRIEF

ABC: Protect the Eastern Golden Eagle

In late 2023, ABC petitioned the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service to request a Threatened or Endangered listing for the Eastern Golden Eagle under the Endangered Species Act. Persistent threats and a slow reproductive rate coupled with a population of only about 5,000 individuals are raising red flags for conservationists.

“The Golden Eagle is a widely recognized icon of North America's western landscapes. Many people are surprised to learn that there is also a subpopulation of Golden Eagles in the East,” said Michael J. Parr, President of ABC. “But this population is threatened. With a host of hazards, including the growing threat of improperly sited wind-energy development, the Eastern Golden Eagle needs immediate attention.”

More Local Bird-Friendly Laws on the Books

Two local laws requiring birdfriendly building designs made headlines recently.

In Wisconsin, conservation groups including ABC won a yearslong legal battle in Madison when that city’s bird-friendly design ordinance survived a court challenge from developers. The city’s Common Council had supported the law unanimously in 2020. It requires new large construction and expansion projects to use modern bird-safe strategies and materials that allow birds to see and avoid glass.

And Newark, the largest city in New Jersey, recently adopted a mandatory bird-friendly materials requirement as part of a land-use and zoning ordinance passed in November. The new rules are based on ABC’s

New Bird Atlas Benefits ABC

ABC is the sponsor of the newly published book Birds of North America: A Photographic Atlas, and we are partnering with the publisher, Johns Hopkins University Press, to offer ABC Members an exclusive discount on orders from its website, press.jhu.edu. Use code HBIRDS24 at checkout for 30% off your order. Scan the QR code below to purchase the book! The code is valid through 2025, and a third of the proceeds from the book will support ABC.

The 560-page hardcover atlas features accounts describing 1,144 bird species recorded in the United States and Canada, including Hawai‘i and Alaska. Author Bruce M. Beehler covers all of the expected North American birds as well as rarities and vagrants from the neotropics, Europe, Asia, and the oceans. ABC President Michael J. Parr wrote the foreword.

model ordinance for bird-friendly construction.

Rare Seabird Listed as Endangered

In January, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service listed the Black-capped Petrel as Endangered under the Endangered Species Act. The seabird, which is found in the Caribbean and the North Atlantic, numbers about 1,000 breeding pairs. Its only known breeding sites are on the island of Hispaniola, in both Haiti and the Dominican Republic.

Recently, ABC and several partner organizations have been attempting to locate a possible breeding site on Dominica, about 750 miles southeast of Hispaniola. (See our

Fall 2023 issue, page 9.) And, we are working with the Caribbean National Wildlife Refuge and other partners to attempt to attract petrels to breed on Desecheo Island, which lies between Hispaniola and Puerto Rico. Learn more at abcbirds.org/ desecheo-trip-2023.

Investment in Motus Fills

‘Critical Research Infrastructure Needs’

In March, the Canadian Foundation for Innovation announced it would invest $3.1 million in the Motus Wildlife Tracking System, the program led by Birds Canada that studies migratory birds, bats, and insects. ABC is helping to lead the expansion of Motus with partners across the United States and the Caribbean through regional, national, and international coordination efforts. (Read more in our Winter 2023 issue, p. 11.)

“This funding will be the single greatest expansion of the Motus initiative, filling critical research infrastructure needs across Canada and elsewhere in the hemisphere,” said Stuart Mackenzie, Director of Strategic Assets, Birds Canada. “This will give us the ability to track and monitor migratory animals throughout

their lives, ensuring we have more scientific evidence available to inform conservation decisions.”

SupportforABC’sMotusprojects comes from Birds Canada, The VolgenauFoundation,thestatesofAlabama,NorthCarolina,andOregon, andtheTareenFilgasFoundation.

Habitat Protection Underway through Conserva Aves Project

In mid-February, ABC and our partners in the Conserva Aves initiative met for two days in Colombia with the Bezos Earth Fund, which established the initiative with a $12 million investment in 2022. Conserva Aves is currently supporting 46 projects in Colombia, Peru, and Bolivia, and it will soon seek proposals from Ecuador. The goal is to conserve nearly 5 million acres in Latin America and the Caribbean by creating or expanding 100 or more strategic protected areas between 2022 and 2028.

Nature Reserve Guide Available in Three Languages

In 2022, ABC and IUCN National Committee of the Netherlands released a manual in English with nine steps to successfully start and maintain privately protected areas (PPAs), which can be a powerful way for communities to conserve local biodiversity. Now, the 108-page

manual, titled Sustainable Nature Reserves: Guidelines to Create Privately Protected Areas, is also available in Spanish and Portuguese.

Find links to all three versions at abcbirds.org/SustainableReserves

Study: Redstart Breeding Range Moves South

Climate change is driving the breeding ranges of many bird species north due to rising temperatures, but that’s not necessarily the impact on all species. Bryant Dossman, a postdoctoral fellow at Georgetown University, and four co-authors recently reported in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences that American Redstarts that winter in Jamaica are experiencing a southward shift in their breeding range in the Upper Midwest.

Over the last 30 years, the redstart breeding range has moved about 310 miles (500 km) south, and the researchers say a long-term drying trend throughout the Caribbean is the likely cause. They found that after long dry nonbreeding seasons, the birds are less likely to survive their northbound migration in spring. But after wet seasons, when insects are more abundant, migration distance had no effect on survival rates. After three decades of these impacts, the range of the redstarts in their study has shifted from a stretch covering northern

Ohio.

‘Alalā Release Planned on Maui

This spring, conservation agencies intend to release the ‘Alalā (Hawaiian Crow) in native forest on the eastern part of Maui after the completion of a federal and state Environmental Assessment.

The bird, which has been extinct in the wild since 2002, is listed as Endangered under the Endangered Species Act. Around 115 ‘Alalā survive at captive breeding centers on Maui and Hawai‘i Island. In the last decade, two attempts to establish wild populations of the species on Hawai‘i Island failed, largely because the ‘Io (Hawaiian Hawk) preyed on the crows. While the forest habitat on Maui is similar to that found on Hawai‘i Island, the ‘Io isn’t present on Maui, offering the crows a better survival chance.

The reintroduction is the work of the ‘Alalā Project, a partnership between the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, two state agencies, and San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance. The team expects to release five to seven birds this spring at the Kipahulu Forest Reserve. Up to 15 individuals may be released over five years, according to the Environmental Assessment.

RETURN OF THE MILLERBIRD

Decades of research, planning, and action by ABC and partners led to a big win for this littleknown Hawaiian songbird.

By George E. Wallace and Chris FarmerSeptember 2011 was a momentous time in the history of the Millerbird, a songbird at risk of extinction and at that time found only in one place in the world: Nihoa Island in the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands. On September 10, we and the rest of our conservation team celebrated as we released 24 Millerbirds on their new home, Laysan Island (Kauō). This was an essential first step toward creating a second “insurance” population for the Endangered species. But three days earlier, on September 7, the journey was off to a slippery start, and our biggest challenge had yet to be overcome.

Precious Cargo

It was one of the most dramatic moments of the expedition: Team member Daniel Tsukayama balanced on slick rocks at the landing site on Nihoa, battling the surf surge. Even worse, he was holding a transport cage containing four of the 24 precious Millerbirds above the swells. As he tried to pass the cage to teammates waiting on the inflatable Zodiac raft, bobbing a few feet away, a swell pushed turbulent, foamy seas up and over Daniel’s waist, threatening to drag him off the rocks. It was seriously hairy!

Thankfully all 24 birds were transferred to our ship, the Searcher, without incident. But the 12 members of the team were wondering: What would the 650mile sea voyage to Laysan bring? If it was rough, would the birds feed? Would they survive? It was one of the greatest unknowns of the whole venture. So, it was like something out of a dream when our passage to Laysan was over the flattest, most breathless seas imaginable — mirror-calm water punctuated only by the occasional flying fish skittering away from the ship, Bottlenose Dolphins surfing our bow wave, or a Black-winged Petrel vaulting by. Below deck, the Millerbirds did well; some even gained weight! It looked like we might actually pull this off. (Spoiler alert: We did!)

More than a decade later, in December 2023, the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) downlisted the Millerbird from Critically Endangered to Endangered due to the ongoing success of the species on Laysan Island. That success was never guaranteed, though. In fact, given the long history of extinctions in Hawai‘i, the odds were not in our favor.

Bird Extinction Capital of the World

The Hawaiian Islands are one of the world’s most isolated archipelagos, an island chain 1,500 miles long strewn across the northern Pacific approximately 2,000 miles from North America and 4,000 miles from Asia. Over millions of years, Hawai‘i was colonized by plants and animals that evolved into a diverse array of species found nowhere else in the world. Unfortunately, the remoteness of the Hawaiian Islands also led to the vulnerability of its bird populations. Humans brought non-native mammals as the islands were colonized, first by Polynesians starting in the 4th century CE and later by Europeans starting in the late 1700s. With people also came many species of non-native plants, insects, birds, and microorganisms. Having evolved in isolation, with no land mammals and without many other common continental species, the native birds were not adapted to living with mammalian predators, such as rats, cats, and mongooses. The plants were not resistant to non-native sheep, goats, cattle, and pigs, or introduced plant pathogens. Many native bird species, especially the Hawaiian honeycreepers, lacked resistance to avian malaria and avian pox virus. Hawai‘i is now known as the “Bird Extinction Capital of the World.” At least 106 species have gone extinct, and most of the remaining 35 species survive in greatly reduced fragments of their former ranges; the majority are listed under the U.S. Endangered Species Act (ESA).

Like most island systems across the world, the main Hawaiian Islands suffered catastrophic losses when continental or more cosmopolitan species invaded. The even more remote Northwestern Hawaiian Islands were not spared, and their delicate ecosystems were even more vulnerable. Until the late 1800s, tiny Laysan, approximately 1,000 acres and over 900 miles from Honolulu, was virtually unknown, but by the 1920s it had been completely degraded. Home to vast numbers of seabirds, Laysan was exploited for its guano during 1896-1909, when Maximilian Schlemmer, a German immigrant, leased it from the Hawaiian territorial government.

Schlemmer introduced rabbits and guinea pigs in hopes of establishing a canned meat business, and he allowed feather hunters to illegally harvest seabirds, removing tons of feathers. The rabbits defoliated the island. Laysan was home to a subspecies of the Millerbird, which was first reported in 1891, but only two decades later, in 1911, researchers visiting to assess damage to the seabird populations suggested that the Laysan Millerbird might need to be moved to other islands because Laysan’s vegetation had been so devastated by the rabbits.

A 1912-13 expedition to eradicate the rabbits on Laysan failed, and it was not until 1923 that the last rabbits were finally eliminated. However, by then, the Laysan Millerbird, Laysan Honeycreeper, and Laysan Rail were all extinct. The Laysan Finch and Laysan Teal survived. Both are now listed

as Endangered under the ESA, and the teal has been the subject of intensive conservation efforts, including its translocation to Midway Atoll and Kure Atoll to establish additional populations. Coincidentally, also in 1923, another subspecies of Millerbird was discovered on Nihoa. Ironically, Laysan eventually would hold the best hope for fending off the potential extinction of the Nihoa Millerbird and restoring a lost element of the Laysan ecosystem.

A Plan Comes Together

Fast forward to 2007: Hawai‘i’s avifauna had never been in a more precarious situation, and ABC, then only 14 years old, was modestly involved in conservation work in the state. We had campaigned to reduce bycatch of albatrosses in Hawaiian fisheries and poisoning of albatross chicks by lead paint peeling from Midway’s World War II-era buildings, but we had not engaged on the conservation of Hawai‘i’s many endangered forest birds or on the equally threatened seabirds nesting on the main Hawaiian Islands. We knew we should do more, and we set about identifying ways to add value to the work being carried out by Hawai‘i’s small but dedicated cadre of state and federal agency biologists, university scientists, and nongovernmental organizations.

Two things leapt out: ABC could increase its fundraising for conservation efforts in the islands and raise awareness about the plight of Hawaiian

birds. Along with colleagues at the Hawai‘i Division of Forestry and Wildlife (DOFAW) and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS), we approached the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation (NFWF), one of the most important conservation donors in the U.S. This outreach led to NFWF developing its Hawai‘i Keystone Initiative. This would not satisfy all of Hawai‘i’s funding needs — estimates of the cost of recovering just ESA-listed forest birds run into the billions of dollars — but it would be a huge step in the right direction. With guidance from Hawaiian conservation experts at DOFAW, FWS, and the U.S. Geological Survey, NFWF and ABC developed a 10-year business plan for the Keystone Initiative centered around raising awareness about Hawaiian birds and three species-specific projects, including translocating Nihoa Millerbirds to Laysan. The goal: to reduce the extinction risk by creating a second Millerbird population and restoring ecosystem function on Laysan by re-establishing Millerbirds there.

A single, isolated small population is at high risk of extinction. Worse, monitoring of Millerbird populations on Nihoa indicated that their populations fluctuated dramatically from year to year, ranging from approximately 194 individuals to 513. These population swings were apparently due to periods of drought and defoliation by non-native Gray Bird Grasshoppers. Due to these drastic swings in population, Nihoa Millerbirds are genetically very homogenous, probably limiting their longterm ability to adapt to environmental changes. A

risk also existed that rats or other invasive species could accidentally be introduced to the island at some point in the future.

‘Introducing Nihoa Millerbirds would represent a continuation of Laysan’s restoration by bringing back a lost member of its bird community.’

The science and ecology underpinning the Millerbird translocation had been completed, and NFWF and ABC’s support combined with additional FWS funding and regulatory approvals allowed the project to kick into high gear. Importantly, Sheila Conant, professor emeritus at the University of Hawai‘i-M ā noa, and her students and collaborators had already conducted much of the critical background research that was needed to plan a translocation, including studies of the ecology of the Nihoa Millerbird and assessment of habitat differences and similarities between Nihoa and Laysan that would inform a translocation. Based on museum specimens, they had assessed the genetic differences between Laysan and Nihoa Millerbirds and found that they were sufficiently similar to each other to justify introducing the Nihoa birds to Laysan. Conant and her former student, Marie Morin, had also analyzed translocation options for passerine birds in the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands that identified Laysan as the best option for the Nihoa Millerbird. And Mark MacDonald had just finished his thesis at the University of New Brunswick comparing invertebrate availability between the two islands and how to determine the sex of Millerbirds in the field (allowing us to select an even sex ratio in the translocation cohort).

A Lost Bird’s Return

In addition, Laysan was ready to receive Millerbirds. FWS had spent over 20 years eradicating invasive, non-native plant species and planting native plants. The area of suitable habitat on Laysan was now several times larger than what existed on Nihoa, and introducing Nihoa Millerbirds would represent a continuation of Laysan’s restoration by bringing back a lost member of its bird community.

The conservation project required a great deal of planning. The logistics of voyages to and from islands hundreds of miles from Honolulu were

continues on p. 24

A Magical Island

Seabirds dominate the land- and seascape of Laysan Island, a special place among the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands. Shorebirds and endemic ducks and songbirds round out the avian wonderland.

Bonin Petrel

Fast Facts: Millerbird

Scientific name: Acrocephalus familiaris

Hawaiian name: The Nihoa Millerbird received Hawaiian names created by the Papahānaumokuākea Marine National Monument Native Hawaiian Cultural Working Group in 2014. Ulūlu is for the Nihoa Millerbird on Nihoa and means “growing things,” in hopes that its population will grow in the coming years. The Nihoa Millerbird population on Laysan is named ulūlu niau, meaning “moving smoothly, swiftly, silently, and peacefully; flowing or sailing thus,” in memory of the calm seas during their translocation to Laysan.

Population: The Nihoa population fluctuates from roughly 200-500 birds; the most recent estimate for Laysan’s population is approximately 300 birds.

Taxonomy and related species: The Millerbird is in the genus Acrocephalus, or Old World reed warblers, of which there are 42 species across Europe, Asia, Africa, and the tropical Atlantic, Indian, and Pacific Oceans. Among the continental species, most have large ranges and populations whereas the 22 island species are mostly confined to single islands, many of them extremely remote. Consistent with many other island bird species, island Acrocephalus, like the Millerbird, are nearly all threatened by invasive, non-native species. Nine island Acrocephalus species (41%) are threatened, and an additional five are extinct. Two subspecies of Millerbird are recognized: the extinct Laysan Millerbird ( A. familiaris familiaris), which was discovered and

described in 1891, and the Nihoa Millerbird (A.f.kingi), which was discovered in 1923. No evidence exists that Millerbirds ever occurred on any other Hawaiian island, although we cannot rule out the possibility that other Millerbird populations went extinct, leaving only the Nihoa and Laysan populations. The nearest other Acrocephalus to the Millerbird, in this case the Nihoa Millerbird, is the Kiritimati Reed Warbler, nearly 1,500 miles to the south in the island nation of Kiribati.

Habitat: Dense, scrubby vegetation near the ground. On Nihoa, it favors ‘ilima ( Sida fallax) and pōpolo (Solanum nelsonii), and on Laysan, naupaka (Scaevola taccada) and kawelu (Eragrostis variabilis), a grass.

Nesting: Both males and females participate in nest building. On Nihoa, nests are constructed low in a shrub and composed of dead grass and Millerbird and seabird feathers. The Laysan Millerbird’s nests are composed of fine rootlets, grass, twigs, and seabird feathers. While the extinct subspecies apparently nested low in tall clumps of kawelu, translocated Nihoa Millerbirds are generally choosing to nest low in naupaka shrubs. Both sexes incubate the clutch of 2-3 eggs for approximately 16 days and care for young during the nestling and fledging stages. The translocated Millerbirds on Laysan can have multiple nests in a breeding season.

Prey: The Millerbird is apparently completely insectivorous, consuming insects and their larvae, including moths, caterpillars, flies, grasshoppers, and small beetles. It is called the Millerbird for feeding on all life stages of the miller moth.

continued from p. 21

considerable. Permits for the project could only be granted after extensive agency review of our plans. And Nihoa and Laysan have strict quarantine regulations to prevent the accidental introduction of non-native organisms, so all our equipment had to be frozen to kill any insects that might be trying to join us; no fresh fruit or vegetables were allowed on either island; and we needed different clothing and equipment for each island.

We conducted two rehearsal trips to Nihoa in 2009 and 2010 to capture test groups of Millerbirds and house and feed them in specially designed cages. Millerbirds eat live insects, so we had to make

Appearance: Like all Acrocephalus reed warblers, the Millerbird is small (averaging 18 g, or a little over a half-ounce), drab, and rather nondescript. Males and females are similar; both are brown to olive brown above and grayish-white below, tinged cream on the lower belly. The bill is dark with a pale base to the lower mandible. The legs are gray. The Nihoa Millerbird is darker and slightly larger than the extinct Laysan subspecies.

Song: No recordings exist of the extinct Laysan Millerbird. The Nihoa Millerbird makes harsh chip notes while the song is two introductory chip notes, followed by a series of chips, squeaks, and churring sounds lasting roughly five seconds. To hear the song, visit abcbirds.org/bird/millerbird

Can traveling birders observe the Millerbird?

Unfortunately, no. Both Nihoa and Laysan are part of the Hawaiian Islands National Wildlife Refuge within the Papahānaumokuākea Marine National Monument and are protected and managed jointly by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, Hawai‘i Department of Lands and Natural Resources, and Office of Hawaiian Affairs. Visitation to the refuge islands is by permit only and is restricted to agency managers, researchers, and cultural practitioners. Furthermore, the islands are extremely remote and accessible only by boat. It is 300 miles from Honolulu to Nihoa and another 650 miles from Nihoa to Laysan.

a bank of Millerbird cages. We distributed traps to capture flies to supplement the captive birds’ diet. We were constantly surrounded by the traffic and din of seabirds including noddies, frigatebirds, terns, petrels, and shearwaters. Nihoa Finches fluttered by on stubby wings and nosed about in the soil. In short — it was magical.

sure we could keep them healthy on frozen and dried foods for up to 10 days — the maximum amount of time we thought we would need to capture the birds on Nihoa, transport them to Laysan, and prepare them for release. Landing at Nihoa was half the battle, since the island is rocky with tall cliffs and has only one suitable landing site. Everything we needed to house Millerbirds and ourselves had to be ferried to the landing site by Zodiac. Getting on the island is a matter of timing the swells and jumping, and sometimes falling, onto slick rocks. A steep, but short, climb up leads to a hollow in the rocks where we established a shaded camp and a site for

We found Millerbirds in dense ‘ilima and pōpolo shrubs and coaxed them into short, very fine, nearly invisible mist nets about 8 feet long using playback of their song. We then disentangled them and brought them to the holding cages in individual transport boxes where aviculturalists Peter Luscomb of Pacific Bird Conservation and Robby Kohley of ABC looked after their care and feeding. Millerbirds are very plain and the sexes resemble each other, but they can be distinguished by subtle differences in their wing and tail measurements. It was common for birds to lose weight during their first 24 hours in captivity and then to rapidly gain it back as they became accustomed to receiving fresh flies trapped on Nihoa and the frozen waxworms we had brought with us. The trials were highly successful and gave us confidence that we could keep the Millerbirds alive. The lingering concern was the nearly 650mile voyage to Laysan. The birds would be in a cabin below deck for over three days. We had no idea how they would respond to the confinement, lighting, air flow, and, above all, motion, which

could be considerable if seas were rough. We timed the translocations for the calmest months of August and September, but nothing was assured.

With some practice under our belts, permits in hand, and gear organized, we departed Honolulu on September 2, 2011, for the first translocation. We arrived at Nihoa after a 300-mile, 31-hour voyage late on September 3. The next day, we set up camp and got to work capturing Millerbirds using the same techniques employed during our rehearsal trips. During September 4-6, we captured 33 Millerbirds and selected 24 for translocation, 13 males and 11 females, all of which were banded with a unique combination of colored leg bands. On September 7, we made a human chain to pass the holding cages down the steep trail to the awaiting Zodiac, bringing us back to where this story began.

Our ethereal voyage concluded late on September 9, when we arrived at Laysan, just as tens of thousands of Bonin Petrels were converging on the island. The next day, we got to do what we had been working toward and visualizing for years. The Millerbirds had all survived and were transferred to their Laysan holding cages, transported by Zodiac to the FWS camp on the island (a much easier landing on gentle sand!), and prepared for release. Laysan is a completely different island from

Part of the 2011 translocation team celebrates the Millerbird release, including (left to right):George Wallace, ABC; Thierry Work, USGSNational Wildlife Health Center; Rachel Rounds, USFWS-Pacific Islands Fish and Wildlife Office; Michelle Cuter, USFWS-Hawaiian Islands NWR; Peter Luscomb, Pacific Bird Conservation; Holly Freifeld, USFWS-Pacific Islands Fish and Wildlife Office; Chris Farmer, ABC; Robby Kohley, ABC; Cameron Rutt, ABC; Tawn Speetjens, USFWS-Hawaiian Islands NWR; Matt Stelmach, USFWS-Hawaiian Islands NWR; and Lauren Greig, USFWS-Hawaiian Islands NWR.

Nihoa — no less magical, but strikingly different. Laysan is flat and sandy with a central saline lake surrounded by a halo of vegetation and low dunes. Like Nihoa, seabirds dominate the scene, but unlike Nihoa, delicate seabird burrows pockmark the landscape, making walking extremely tricky and incredibly stressful. Laysan has its own finch, and they are bolder and more inquisitive than the Nihoa Finches.

A Momentous, Inspiring Accomplishment

Laysan is teeming with flies. Their loud hum across the entire island is the first thing you hear in the morning before the seabirds wake up. A person’s body is always covered with flies as they explore every patch of exposed skin, including lips, eyes, nose, ears — nothing is spared. As 12 Millerbirds were fitted with radio transmitters for post-release monitoring, they captured flies right off our hands. The birds were definitely not going to have any trouble finding food! We carried the birds in special cages and released them into the wild in a large patch of dense naupaka, a native shrub, at the northern end of the island.

Patterned after the first translocation, we conducted a second journey with 26 birds in August 2012,

bringing the total released to 50. On the second translocation, Conant, who had devoted so much of her career to the study of Millerbirds, was able to join the expedition and release birds onto Laysan — literally a dream come true. The new Laysan population of Millerbirds was monitored continuously through fall 2014. Almost immediately, it was apparent that this new population was destined to succeed as the birds started breeding less than a month after the initial 2011 release. Monitoring has been difficult in recent years due to reduced funding, but the last full survey in 2019 found Millerbirds have expanded across the island with an estimate of over 300 birds, and quicker spot trips have confirmed the birds are continuing to thrive on Laysan.

It’s difficult to overstate how momentous the successful establishment of a Millerbird population on Laysan is among Hawaiian and global conservation efforts. Its success is testament to the value of deep background preparation and planning and a passionate team with diverse expertise. In the context of Hawaiian bird conservation, it is inspiring at a time when so many Hawaiian birds are teetering on the brink, and it provides a template for future translocations that could be undertaken for other species, such as the Nihoa and Laysan Finches.

In the global context, it stands out as among the most logistically complex avian translocations

ever attempted, and our experiences could aid in translocations of other island species, in particular other threatened birds closely related to the Millerbird (Acrocephalus reed warblers). IUCN’s downlisting is an acknowledgment that the risk of extinction has been significantly reduced. Sadly though, we realize that the new Laysan population may not be enough to safeguard the Millerbird indefinitely into the future. Laysan will be relatively safe from sea-level rise for over 100 years, but it is still a low island and therefore vulnerable to catastrophic weather, including hurricanes or overwash by ocean waves due to climate change. For this reason, the Millerbird’s status under the ESA is not likely to change for the better anytime soon. However, our team’s work has restored a critical component of the Laysan ecosystem and given the Millerbird time and hope for the future.

George E. Wallace recently retired after 18 years with ABC; in that time, he served as Vice President for International Programs, Vice President for Oceans and Islands, Chief Conservation Officer, and Director of International Programs and Partnerships. He is now an ABC Ambassador.

Chris Farmer, ABC’s Hawai‘i Program Director, has worked on bird conservation in the state for 20 years.

The Millerbird translocation project was led by FWS, co-manager of the Papahānaumokuākea Marine National Monument, in collaboration with ABC. We are grateful for the participation and support of the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation, the University of New Brunswick, University of Hawai‘i, Pacific Bird Conservation, Pacific Rim Conservation, the USGS National Wildlife Health Center, and the Office of Hawaiian Affairs. The following 26 people (listed with their affiliations in 2011-12) made up the translocation crews: George Wallace, Chris Farmer, Robby Kohley, Cameron Rutt, Daniel Tsukayama, John Vetter, and Michelle Wilcox of ABC; Rachel Rounds, Holly Freifeld, Sheldon Plentovich, Annie Marshall, and Fred Amidon of the USFWS-Pacific Islands Fish and Wildlife Office; Thierry Work of the USGS-National Wildlife Health Center; Sheila Conant of the University of Hawai‘i; Peter Luscomb and Eric VanderWerf of Pacific Rim Conservation; Michelle Cuter, Tawn Speetjens, Matt Stelmach, Lauren Greig, Toni Caldwell, Claudia Mischler, and Amy Munes of the USFWS-Hawaiian Islands NWR; Walterbea Aldeguer of the Office of Hawaiian Affairs; Ryan Hagerty of the USFWS National Conservation Training Center; and Kevin Brinck of the USGS-Hawaiian Cooperative Studies Unit.

SEARCH ON!

Just over two years since the Search for Lost Birds began, the initiative has rediscovered species, formed partnerships for conservation and research, and renewed interest in the world’s most elusive birds.

By Matt Mendenhall

When John Mittermeier was 15 years old, he received the book Threatened Birds of the World, a large volume published in 2000 covering more than 1,200 species at risk of extinction. “I saw a distribution map for a bird in the South Pacific that was nothing but question marks, and that just completely captivated my imagination,” he says. “I have never looked back since.”

Indeed, he has not. Not only does Mittermeier hold a Master’s in ornithology from Louisiana State University and a PhD in biodiversity conservation from the University of Oxford, but he also has observed more than 6,000 bird species in 120 countries. And he has co-authored more than 30 papers, articles, and other publications about birds and conservation.

Today, Mittermeier has followed the path that captured his imagination more than 20 years ago. As the Director of the Search for Lost Birds, a collaboration between ABC, Re:wild, and BirdLife International, he is laser-focused on Earth’s most poorly known birds and the rarest of the rare. His position has enabled him and many colleagues to replace question marks on range maps by locating species that had eluded searchers for at least 10 years. And the most exciting aspect of the Search for Lost Birds is that it’s just getting started.

A 25-Year Legacy

The Search for Lost Birds initiative was founded in 2021, but ABC first got involved in looking for lost species about 25 years ago. In the late 1990s, the colorful Yellow-eared Parrot of Colombia’s High Andes was considered by many to be lost and possibly extinct. But in April 1999, a group of researchers sponsored by ABC and Fundación Loro Parque discovered a group of 81 of the spectacular birds.

The species relies on the wax palm for food and nest and roost sites, but the tree was becoming scarce due to its use in Palm Sunday celebrations as well as unsustainable logging. Soon, the organization Fundación ProAves was founded in part to protect the parrot, and it organized a campaign to save the wax palm. Now, after more than 20 years of conservation work, the parrot’s population exceeds 2,600 individuals.

Similarly, in 2016, ABC and the William Belton Conservation Fund provided financial support to a

conservation partnership between the Smithsonian Institution and several scientific organizations in Venezuela for its search for the Táchira Antpitta. The plump brown forest bird had been missing since ornithologists first described it in the mid-1950s.

The five-person search team located the antpitta in June 2016 at the same location it had been discovered decades earlier in a remote part of what is now El Tamá National Park in western Venezuela. The team took the first ever photos of a living Táchira Antpitta and made the first recordings of its sounds. The species, classified by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) as Critically Endangered, is believed to number no more than 50 individuals.

After the success of these projects and the rediscoveries of other lost species, ABC looked for ways to formalize future searches. Soon, the Search for Lost Birds was established; its model was Re:wild’s Search for Lost Species, an effort that has rediscovered 12 species of plants and animals around the world since 2017.

“We’ve applied Re:wild’s clear criteria for what ‘lost’ means to birds,” Mittermeier says. “It’s 10 or more years with no independently verifiable documentation. The species are not declared extinct by the IUCN, and nobody’s definitely photographed, soundrecorded, or collected genetic material of them in the past 10 years.”

Quick Successes

When the Search for Lost Birds was announced in December 2021, the partners created a top-10 list of lost bird species to target for searches. In just over two years, two of the 10 have been located: Colombia’s Santa Marta Sabrewing and Madagascar’s Dusky Tetraka, as well as one that wasn’t on the list: the Black-naped Pheasant-Pigeon of Papua New Guinea.

The sabrewing is a large green-backed hummingbird found only in the Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta mountains of northern Colombia. Males have a stunning iridescent blue throat and breast, and females have grayish-white underparts.

The species was lost to science for 64 years before being photographed once in 2010, only to become lost again before its rediscovery in 2022. Yurgen Vega, an experienced local birdwatcher, was the

first to spot the bird that July. “The moment when I first found the Santa Marta Sabrewing was very emotional, I really couldn’t believe it,” he says. “The adrenaline, the thrill of that moment of rediscovery, it’s hard to fully describe just how exciting it was.”

Seven months later, professors Carlos Esteban Lara and Andrés M. Cuervo of Universidad Nacional de Colombia independently found other individuals in additional locations within the same area. This prompted ABC and other collaborators to immediately begin monitoring and studying the extremely rare population.

The researchers have focused on the birds ever since, and in March, they published a preprint of a new study of their findings about the sabrewing’s behaviors, habitat, and range. Esteban BoteroDelgadillo, lead author of the study and Director of Conservation Science with SELVA: Research for Conservation in the Neotropics, says the species appears to be “an example of microendemism, as it seems to be restricted to a limited area within the world’s most important continental center of endemism. We are excited to have the opportunity to continue studying this bird because there are still huge knowledge gaps regarding its biology and distribution. Filling these gaps will help achieve our ultimate goal of finding long-lasting conservation solutions.”

Led by Professor Lara, the partners have worked closely with the Indigenous communities in the region since the sabrewing’s rediscovery. That work

will continue, including discussions with local communities about further research, conservation measures, and if and how to arrange access for birdwatchers. While ecotourism has been an effective tool for supporting conservation in parts of the Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta, it also has the potential to create challenges for endangered species and people living in the region if not managed carefully.

“It feels like we have cracked the code behind this amazing species and understand, for the first time, something about it and how it managed to disappear from science for most of the past hundred years,” Mittermeier says. “From a Lost Birds perspective, this is just about the most exciting result you can hope for.”

for 15 years. As a student in the 1990s, he was on Peregrine Fund teams that found the lost Madagascar Serpent-Eagle and Red Owl.

Two teams of biologists set out just before Christmas 2022 toward places they hoped to find the tetraka. René de Roland and Mittermeier’s group went toward the site where the last tetraka had been documented more than 20 years earlier. The trip took 40 hours of driving on “terrible roads,” Mittermeier says. And after a half-day hike into the mountains, “we got to the spot and all the forest was burned and destroyed.”

The searchers spent 10 days “going up and down brutally steep mountains hoping to find this bird but not being sure whether it was there and not knowing what it sounded like. It’s a cryptic understory bird. I remember thinking it felt like playing outfield in a baseball game in the pitch-black hoping that you’re going to catch a fly ball when you can’t see anything.”

The other team, led by Peregrine Fund biologists Armand Benjara and Yverlin Pruvot, struck paydirt first, capturing a single tetraka in a mist net on the Masoala Peninsula on December 22. Then, on January 1, 2023, the second-to-last day of the expedition, Mittermeier found a tetraka near Andapa, more than 100 miles north of the first sighting. “I was walking along a really loud, rushing river in the mountains, and I was exhausted after all this field work. I had seen virtually no birds the entire morning and was thinking, ‘we’re probably not going to find this bird.’ I started walking back and just in that moment, this little bird started scooting up from the understory by my feet. It was the Dusky Tetraka.”

Tallying Lost Birds

In addition to mounting expeditions for missing species and follow-up conservation projects, Mittermeirer and his colleagues at ABC, Re:wild, BirdLife, and the Cornell Lab of Ornithology recently conducted a study to determine how many bird species around the globe qualify as “lost.” The answer: 125 out of more than 11,000.