19 minute read

SOCIALITE

Socialite 4

Beyond Budapest: Dispatches From Lake Balaton

In a recent interview, quoted on the Guardian website, Budapest city mayor Gergely Karácsony said, “We want to spread out the spots in the city that are touristically interesting, and change the type of people who come. It shouldn’t only be bachelor parties and booze – we want to rebrand ourselves a bit.”

DAVID HOLZER

I’ve just spent several days at Siófok on Lake Balaton, a tourist destination that’s easy to reach from Budapest and has an entire tourist infrastructure already in place.

With that in mind, I’d suggest that promoting awareness of “spots” right across Hungary that are touristically interesting could be stepped up a little.

Before I came to Hungary, I had no idea the Balaton even existed. A Hungarian friend of mine has met groups of British lads at the lake; they rent a car at Budapest Airport and head up for a short break. But they’re in the minority.

What struck me about my few days in Siófok (about 105 km southwest from central Budapest) was just how different the Balaton sun, lake and fun vacation experience is from the British seaside or Mediterranean equivalent.

We’ll get the lake bit out of the way first, shall we? I wasn’t quite prepared for how far I’d have to walk to get into comfortably swimmable water. It felt like I was in the middle of the lake before it was chest high. Apparently, the water’s much deeper on the less obviously touristic northern side of the lake.

This shallowness makes the lake pretty safe for children, I’d guess. It also means that there aren’t strong currents to whisk the SUPpers (the increasingly numerous stand up paddle boarders) out into dangerous waters.

If a storm blows up, as it did on our last day, it’s easy to see it coming from across the lake, which leaves ample time to haul out your kids. But, even in the height of the storm, there were still people in the lake optimistically throwing balls to each other.

Wet or Warm

Although we’re having the wettest summer I’ve yet experienced in Hungary, the sun bit is normally a breeze. Hungary tends to get hot in May and, apart from summer storms, stay that way until October.

But, unlike the Med, there’s a strange softness to the Hungarian summer sun. Perhaps it’s because the landscape seems to remain green throughout and never really looks bone dry and parched.

Now to the fun, which is 100% Hungarian. Although I love Budapest, its center does have an air of “any-city-inEurope” blandness about it. This isn’t just down to the Starbucks and McDonald’s joints. Or the retail brands being the same as those on any shopping street anywhere in the developed world.

It’s also to do with the fact that what passes for hipster in Budapest is a pale version of what you’d find in London, Berlin, Amsterdam or Madrid. If you really want to get a sense of what Budapest is about, you have to head away from the area around Király utca and pretty much the entire District VII.

Cross a bridge over to the Buda side and the streets immediately feel more authentically Hungarian. Or head out to a

Siófok lies on the southern shore of Lake Balaton. Photo by Geza Kurka Photos / Shutterstock.

district like the 10th, home of Budapest’s Chinatown at the Monori Center in Kőbánya, about 30 minutes by bus from Deák Ferenc tér, and you are really in another world.

But unless, like me, you like to drift aimlessly around cities and, ideally, get lost, you really need a reason to visit off the beaten track Budapest. How many tourists are going to come to Budapest to taste authentic Chinese food, for instance?

Unless Karácsony is thinking about reviving long-lost secret Budapest attractions or creating them – a House of Terror theme park perhaps – it’s hard to know where he plans to direct tourists for wholesome family fun. (Mind you, there is that bizarre structure you see to the right just before you enter Nyugati station which, I’m told, was once a zoo. That has potential, I’m sure.)

Fun for All

Fun on Siófok’s main drag, Petőfi sétány (promenade), is certainly nagyon Hungarian and pretty much for all the family. This is the case even after midnight, when the street is jumping and thronged with bronzed young Hungarians: men with arms the size of legs, and women spilling out of glittery handkerchiefs.

At this time of night, the atmosphere on a street in the United Kingdom or somewhere like Magaluf in Mallorca, where young Brits congregate, would, in my experience, be pretty tense.

If violence hasn’t already erupted, it’s a constant threat. People are staggering or passed out drunk and you’re in constant danger of stepping into pavement pizza.

On Petőfi stny at midnight, there was all the good stuff and none of the horror. Music blared out of bars, the bleep and whoosh of techno indistinguishable from the sounds made by the machines in the amusement arcades. The air was so thick with the aroma of frying food it was probably hardening our arteries without us eating a thing.

What was left of that atmosphere was good-humored and friendly, despite the colossal amounts of alcohol being consumed. I assume there was a Slow Screw On The Lake cocktail on offer somewhere but, sadly, I didn’t see it.

I must admit I was surprised to discover that some overseas “bachelor parties and booze” tourists do head for the Balaton. But, if they behave like decent young Hungarians, it’s a good sign.

Perhaps an enterprising tour operator could offer a bus service from Budapest Airport out to the Balaton. Such a service could also venture out to other places of interest in the Hungarian countryside.

Because, in my experience, one of the deterrents to traveling more widely in Hungary is navigating the rail network if you speak only a few words of the language. Something else for Hungary’s tourist experts to ponder.

The Best Rosé now a Wine for all Seasons

Hungary is currently awash with rosé, a wine style in which the country’s vintners generally excel, often by skillfully channeling the crispy acidity and succulent red fruit of the indigenous Kékfrankos grape into the glass.

ROBERT SMYTH

For many years Hungary has pumped out millions of hectoliters of well-made, easy to drink, fruity rosé that’s at its peak pretty much as it hits the shelves and is meant to be sipped during the spring and summer following its harvest and vinification. More recently, increasingly sophisticated rosés are being made that can be enjoyed any time in the year of their release, and for another year or two beyond that.

From the Mátra wine region, near the town of Hatvan, the Nagygombos winery, which cultivates 90 hectares in one contiguous vineyard block, describes itself as a rosé specialist.

It cites factors that are prime for making the pink stuff, such as the cool northern climate that allows the grapes to ripen gradually over the growing season, slowly acquiring flavors while preserving their substantial acidity (essential for rosé), and the lime nyirok clay bedrock with sandy loess soils that also encourage fruitiness, as well as the choice of grape varieties.

Nagygombos, where the wines are made by Anna Barta (her father, Károly, is the owner of Tokaj’s prestigious Barta winery), has released a trio of rosés from the 2019 vintage that all show nice nuances of the wine style, with the first two being ideal for imbibing on hot summer days, and vinified fully in stainless steel.

The pale salmon-colored Nagygombos Játékos Rosé 2019, is a blend of Merlot and Cabernet Franc, with thirst-quenching citrus fruit, especially grapefruit, to go alongside the cherry, raspberry, plus those small red berries with a sour twist, and watermelon. Its lively acidity is counterbalanced by a touch of residual sugar. It is playful as its name (in Hungarian) implies and a refreshing tipple for hot nights (and days).

The bright salmon-colored Nagygombos Mosoly Rosé 2019, made solely from Kékfrankos, positively oozes ripe strawberry, then raspberry and cherry, and is a good showcase of the grape variety regarding its capacity to convey its fabulous fruit to rosé, with that mouth-watering, tongue tingling acidity keeping it fresh.

These two, which are fun to taste alongside each other (though I prefer the fresh red fruitiness of the latter) cost a very reasonable HUF 1,150-1,200 from Auchan, CBA, Reál and Artizan webshop.

More Sophisticated

The Mátra-based winery also has a more sophisticated rosé up its sleeve. Nagygombos Borászat Barta Anna Gamay Noir Rosé 2019 is made from the Gamay Noir grape, the French grape that hails from Burgundy and is most widely associated with Beaujolais. It is aged both in stainless steel and oak, with the oak bringing considerable texture and spicy flavors.

More like an oaked white wine in terms of texture than a rosé, but also with a touch of red wine tannin, this layered wine has raspberry and sour cherry, accompanied by complex pomegranate, caramel and yeasty notes. It costs HUF 1,690 from matraiborokhaza.hu.

There are also some rewarding rosé finds to be made around Lake Balaton. From Balatonfüred, the Figula winery serves up a light and suitably zesty Rosé Cuvée 2019 (Cabernets Sauvignon and Franc, plus Kélfrankos and Zweigelt), but it is the 100% Cabernet Sauvignon Bella Róza Rozé 2019 (HUF 4,250 from Bortársaság), made from grapes from Balatonszőlős, which raises the rosé stakes.

Spontaneously fermented; half in oak (steamed, not toasted, in order to avoid woody notes but still enhance the texture), half in tanks. An onion skin color, with orange peel and marmalade notes, it is complex and spicy with great mouth-feel.

From just a few kilometers away, on the Tihany Peninsula (which juts out into Lake Balaton, giving it a unique mesoclimate, while it also has volcanic basalt soils), comes Tihany Rozé 2019, a co-production between local winemaker Dávid Bökő and Gellavilla, the winery of Bortársaság head/ part-owner Attila Tálos.

It’s made from Kékfrankos and Zweigelt grapes, with a bit more of the former, harvested on two separate dates from a remarkable spot between Sajkod Bay and Tihany’s reedy Külső-tó (Outer Lake), about 200 meters from Lake Balaton.

The grapes underwent whole-bunch pressing and brief settling, then were fermented spontaneously (but separately) in temperature-controlled tanks. After lengthy ageing on lees, blending was carried out in February.

The final wine was bottled in mid-May. It is light and airy, but also really elegant with good mouthfeel and length, and a lovely balance between ripeness and acidity. Expect to pay HUF 3,750 from Bortársaság.

Contemporary

It’s also available in the Szőlősi Kocsma, the now cool and contemporary Balatonszőlős pub (you’ll find it in that town at Fő utca 10), fabulously renewed by Attila Tálos. This is a great place for eating as well. While on that theme, Tihanyi Vinarius is a strikingly restored winethemed restaurant overlooking Tihany’s Inner Lake, at Kiserdőtelepi út 15. It was originally built in 1820 by the Tihany Abbey to house its wine cellar and press house.

Franz Reinhard Weninger, an Austrian winemaker who makes wine following biodynamic principles in Balf, in the Sopron wine region on the Hungarian side, and in Horitschon in the Burgenland, on the Austrian side, makes Rózsa Petsovits Rosé; a tribute to his grandmother, who had Hungarian origins.

It comprises Pinot Noir and St. Laurent from the Burgenland and Syrah from Sopron. After a little skin contact, it underwent slow and spontaneous fermentation in concrete vats and used barrels.

This exciting, edgy wine is unfined and unfiltered, very dark for rosé, approaching pale ruby in color, really earthy with juicy sour cherry and raspberry notes, with a wild, untamed feel, almost on the edge of refermenting as Weninger uses very little sulfur. The 2019 costs HUF 3,850 from Bortársaság.

From Szekszárd, the Dúzsi winery has a six pack of wild-yeast fermented rosés (Fajta-Rozé Válogatás 2019), made by Bence Dúzsi, the son of Tamás Dúzsi (also known as “The Prince of Rosé”) from six different varieties and gives the winery’s classic Kékfrankos rosé free as the seventh (HUF 13,900 from Bortársaság). The grapes for the six come from plots that are being transitioned over to organic cultivation. It is always a joy to sniff out the subtleties of each variety.

30 YEARS OF FREEDOM

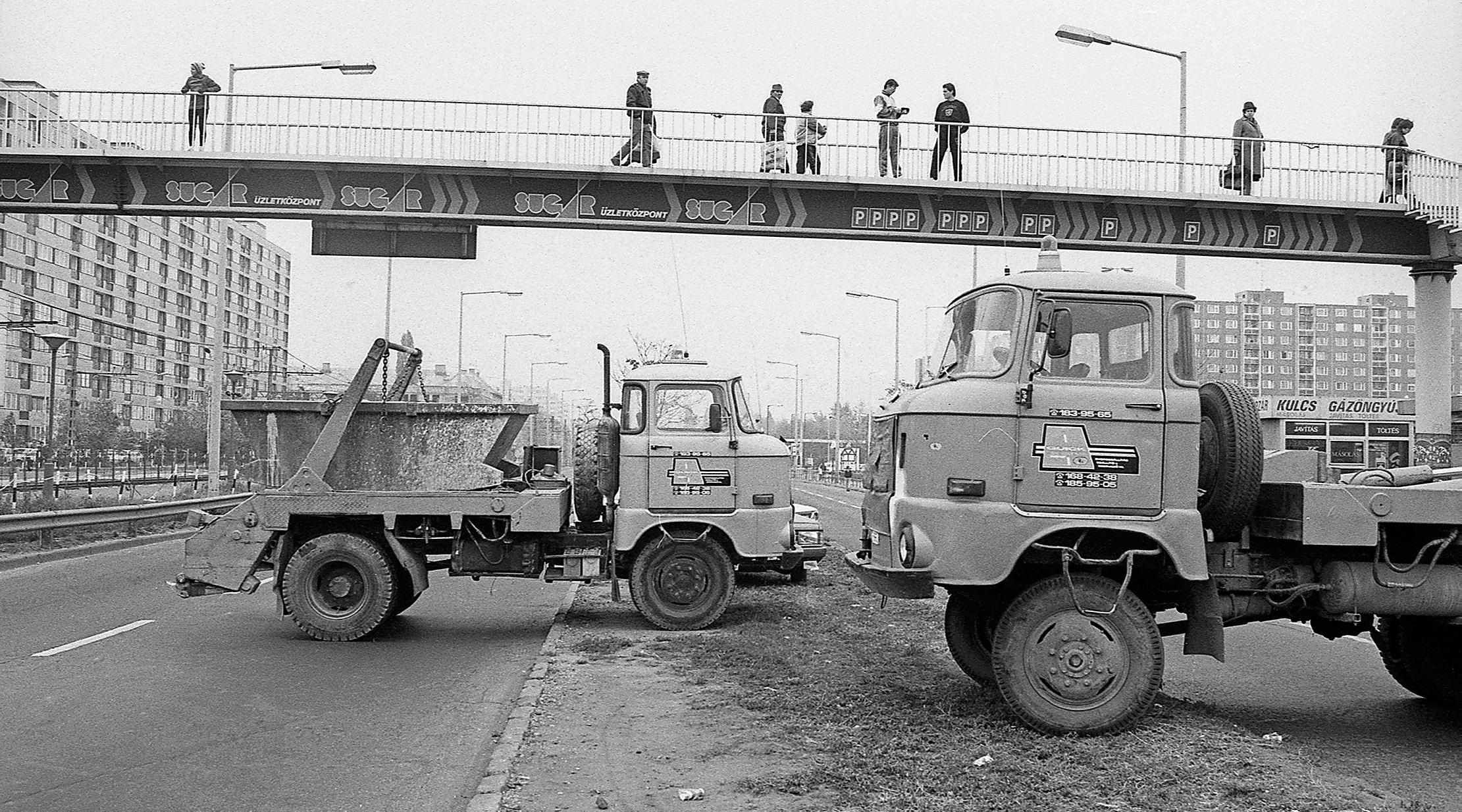

Aerial photo of the intersection of Budaörsi út and the M1-M7, with Beregszász út on the left, and an auto car service on Boldizsár utca on the right (Budapest, District XI). Photo by Fortepan/Zoltán Szalay.

Taxi Blockade: A Chronicle of Four Remarkable Days

In the last days of October 1990, the price of petrol in Hungary soared overnight by about 65%. Protesting against the increase, taxi drivers and private carriers first blocked roads in Budapest, then nationwide, paralyzing traffic for days. It was serious enough that Prime Minister József Antall was forced to work from his hospital bed to find a solution for what became known as the “taxi blockade.”

BBJ STAFF

In doing its best to reduce the huge public debt inherited from the previous regime, the Antall government has had to deal with a series of serious conflicts and conflicts of interest. Thirty years on, the October 1990 taxi blockade still divides politicians and public alike: many recall it as the first mass demonstration in democratic Hungary; others see it as an arbitrary action by a group of entrepreneurs that paralyzed others.

The price increase was officially announced on October 25, but had been preceded by controversial rumors. On October 19, the first news item about the possible price increase appeared in Népszava entitled “Betrayal: HUF 56-62 Gasoline is Coming”, while Magyar Hírlap reported on October 24 that petrol would become more expensive from October 29.

State news agency MTI reported that gasoline price increases were not on the agenda of the government’s October 25 meeting. Nevertheless, a 65% increase in fuel prices was announced at a parliamentary press conference that afternoon. According to the government, the price increase was triggered by the decline in Soviet oil supplies and by the First Gulf War, which had begun on August 2.

Outraged taxi drivers gathered on October 25 at Hősök tere in Budapest and then at Kossuth tér, in front of the Parliament, where they met with Minister of Transport Csaba Siklós, although he refused to receive their petition.

The taxi drivers decided to widen their protest: keeping in touch with each other via their radio network, they blocked all the bridges in Budapest, crippling the city’s traffic flow. From midnight, the blockade went nationwide, joined by both private and freight carriers.

The next day, October 26, movement was almost impossible on the country’s main roads and in larger cities, with traffic also building up at the borders. Budapest Ferenc Liszt International Airport, then known as Ferihegy Airport, could not be reached from the capital, only the metro ran in the inner areas of the city. Demonstrators, however, did let ambulances and other emergency vehicles and lorries transporting food through their blockades.

Government spokesman Balázs László described the action of taxi drivers as illegal on the morning of October 26, citing the fact that it had not been announced 72 hours earlier in accordance with the provisions of the Assembly Act.

The government had certainly been caught unawares by the protest; four of the 11 ministers were abroad, and Prime Minister József Antall was hospitalized. (As is now well known, but was not at the time, the prime minister had been diagnosed with non-Hodgkin lymphoma in the summer of 1990. He had undergone an operation just two days before the blockade, and would not see out his term in office: he died on December 12, 1993.)

Order by All Means

In his absence, the Minister of the Interior, Balázs Horváth, performed the duties of the Prime Minister, and announced that the government would restore order by all legal means. In a speech broadcast on radio and television, he justified the government’s action and announced that three crisis teams had been set up.

President Árpád Göncz made a public address on television that evening,

Margit híd (Margaret Bridge) during the blockade. Photo by Fortepan/Zoltán Szalay.

proposing that the government suspend the increase in petrol prices and, in response, that the taxi drivers end their blockade.

On October 27, Hungary awoke to a complete blockade of its roads. Taxi drivers and haulers, along with members of the public who joined them, paralyzed the country. Road barricades were erected in an estimated 600 locations, affecting a total of 105 settlements. In Budapest, with the exception of the Chain Bridge, all Danube bridges were closed and 25 major junctions were blocked. German Chancellor Helmut Kohl and Austrian Chancellor Franz Vranitzky both offered to help.

Negotiations between the carriers and the government lasted all day. In the evening, it was agreed to publish a joint statement. In this, the government announced that it would present a solution to a meeting of the Conciliation Council to be held on October 28, through which a discount of HUF 10 per liter could be envisaged under certain conditions. The agreement was made conditional on the lifting of the blockade.

Based on a preliminary agreement between the government and the carriers, at midnight, National Chief of Police Győző Szabó called on the protesters to remove the barriers.

By the morning of October 28, the blockade had eased somewhat, though it was far from universally lifted. At noon, the meeting of the Conciliation Council began at the Ministry of Social Affairs and Labor and was broadcast live on television at the request of the carriers.

On behalf of the government, Minister of Industry and Trade Ákos Péter Bod and Minister of Finance Ferenc Rabár led the negotiations, the workers’ delegation was headed by Pál Forgács, President of the Trade Union Roundtable and the Democratic League of Independent Trade Unions (FSZDL), and Sándor Nagy, National Association of Hungarian Trade Unions, while the employers were represented by János Palotás, President of the National Association of Entrepreneurs (VOSZ).

The meeting was chaired by István Orbán, vice president of the Hungarian Chamber of Commerce.

According to the agreement reached that evening, the increased petrol prices were to be reduced by HUF 12 from midnight on October 29, and the new prices would be valid until laws related to price liberalization come into force. lifted throughout the country, and traffic was restored.

After signing the agreement, Prime Minister József Antall made a television statement to the television from his hospital bed. In what perhaps inevitably became known as his “pajama interview”, Antall analyzed the situation in the country, evaluated the compromise that had resolved the crisis, and acknowledged that his government had made mistakes in preparing for the announcement of the gas price increase.

He said there were no losers or winners in the situation and promised that the government would not act against those involved in the “civil dissatisfaction movement”.

Viewed from this distance, it would be easy to regard the taxi drivers’ blockade simply as an example of mass industrial unrest, but not everyone agrees with that assessment. In 2016, the Institute and Archive for the History of Regime Change (Retörki) analyzed the events and background of the blockade in a twovolume, 700 page summary.

“Here, the program was the overthrow of the government,” remarked Zoltán Bíró, the general director of Retörki, at the time of the presentation of the dissertation. According to him “this is how the SZDSZ wanted to achieve what it did not succeed in the elections.”

He added that the country had been close to a civil war situation developing in those days.

Subsequently, at the spring session of Parliament, President Árpád Göncz submitted a bill offering an amnesty. The taxi blockade had resulted in hundreds of thousands of participants nationwide committing crimes because the demonstration was not announced 72 hours before it began and had paralyzed the operation of public utility plants. With the enactment of the Public Amnesty Act, the state dropped charges.

Political parties had also joined the argument: opposition SZDSZ politicians spoke at the barricades, and the ruling Hungarian Democratic Forum tried to win sympathy for its cause. Viktor Orbán, the young leader of the then liberal opposition Fidesz party, said in a speech to parliament after the three-day crisis that the government had lied because it denied that it was preparing to raise prices before the announcement.

Dented Prestige

The blockade severely damaged the prestige of the Antall government, which had proclaimed a “social market economy.” Minister of the Interior Balázs Horváth was unable to handle the situation in place of the ailing Antall; President Árpád Göncz had managed to take some of the heat out of the situation by stating that, as the head of state and commander-in-chief of the army, he would forbid its deployment. Plenty of simple sympathizers took the side of the taxi drivers, offering food and drink to those manning the barricades.

The four-day blockade can be seen as the beginning of the end for the first freely-elected post-communist Hungarian government, but also the first serious test of the country’s fledgling democracy. Ironically, though, rather than the highly active Free Democrats (SZDSZ), it was the reborn Socialist Party (MSZP) under Gyula Horn that was to reap the laurels of dissatisfaction by winning the 1994 general election.

The success of the taxi blockade was basically down to two things: in 1990, there were more taxi drivers in Budapest than in New York, according to an Origo article from 2005, which claimed nearly 20,000 drivers held a license and another estimated 5,000 worked illegally. As regulations were tightened through the ‘90s and subsequent decades, more and more gave up the profession.

Kossuth Lajos tér (Budapest, District V), in the background the MTESZ house on the left. At center right is one of the main organizers of the taxi blockade, Pál Horváth. Photo by Fortepan/Zoltán Szalay.

(Editor’s note: If that number makes it seem everyone must have been a taxi driver, perhaps they were. Certainly, I was told when I first arrived in Hungary in 1998 that Gábor Demszky, the SZDSZ Mayor of Budapest from 1990-2010, had fought his first election partly on a campaign of knowing the problems of the city’s streets better than other candidates from his time as a taxi driver.)

Another factor in the success was that the taxi drivers had a communication network that was only available to the police, ambulance service and the army at the time. In a time before widely available cell phones, CB radio provided a system that allowed the demonstration to paralyze the country.

At the same time, it is thoughtprovoking to note that CB communications are not encrypted, so anyone with a handset (including law enforcement units) could easily listen in, yet the organization was successful. According to some, this was another reason for the introduction of the so-called CEPT standard, which practically buried CB radio alive.

New ZOE

100% ELECTRIC