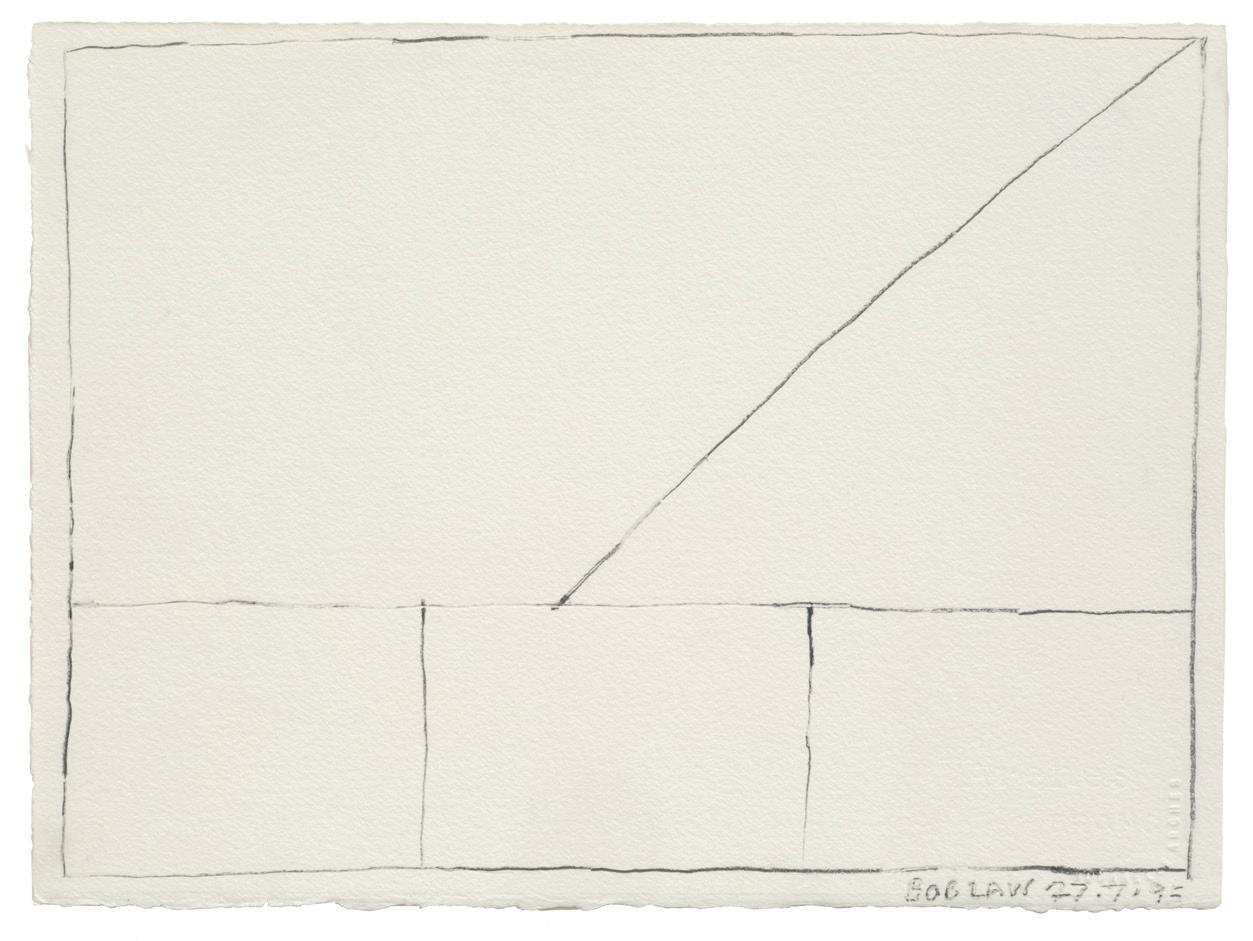

Drawing 10.5.59 1959

Pencil on paper

25.3 x 35.5 cm | 10 x 14 in

Drawing 25.5.59 1959

Pencil on paper

Drawing 10.5.59 1959

Pencil on paper

25.3 x 35.5 cm | 10 x 14 in

Drawing 25.5.59 1959

Pencil on paper

The man who seems to me to have travelled furthest down the avant-garde road to nothing and nowhere is Bob l aw.

–Fyfe Robertson1all I know about method is that when I am not working I sometimes think I know something, but when I am working, it is quite clear that I know nothing.

–John Cage2This is a story about nothing. or more precisely, about the paradoxical process whereby nothing can in fact become something. It begins with a piece of paper and an eraser. The year is 1953 and a young Robert Rauschenberg has just returned to New York from an eight-month-long-trip to Italy and North africa with his friend, Cy Twombly. getting back to work in the wake of his White Paintings (1951) and Black Paintings (1951–53), Rauschenberg looked for a way to extend what he called ‘the monochrome no-image’ into the realm of drawing. He came upon the idea of erasure as a continuation of his search for a zero degree of artistic production. after ruling out the idea of erasing one of his own works, Rauschenberg approached the more senior artist, Willem de Kooning, in order to obtain a drawing that he might use in his aesthetic experiment. after extracting a drawing from the reluctant artist, Rauschenberg began the laborious process of using a large number of erasers to remove De Kooning’s crayon markings from the surface of the sheet of paper. The result was Rauschenberg’s Erased de Kooning Drawing (1953; p.7), a work that is now heralded as one of the more important conceptual and aesthetic milestones in the trajectory of postwar contemporary art.

Rauschenberg’s gestural erasure of De Kooning’s drawing was not simply a neo-Dadaist negation of a more established artist’s overpowering aura, as is commonly discussed (after all, De Kooning wittingly gave him the drawing). In painstakingly removing the expressive traces of the original artist’s hand through the concrete friction generated by his own bodily movements, Rauschenberg enacted a kind of reverse archaeology. By rubbing the material evidence of De Kooning’s presence away, he revealed the blank surface of the paper to be a receptive screen on which one could project anything. This physical social history sits upon the surface of Erased de Kooning Drawing as much as it does on any surface that has been worked on over and over again, emphasising the fact that this erasure was as much a phenomenological act as it was an aesthetic one. The transformative character of Rauschenberg’s radical gesture is that it turned something into nothing. This was, however, a nothingness pregnant with endless possibilities, since any erasure always leaves behind the traces and ghosts of past incidents, chance encounters and conversations as much as it does a purportedly ‘blank’ receptive surface.

Famously John Cage emphasised this aspect of Rauschenberg’s work in 1961 by referring to the painter’s White Paintings (which he had much admired when Rauschenberg produced them in summer 1951 at Black Mountain College, Black Mountain, NC) as ‘airports for lights, shadows, and particles’. In this sense, the matte monochrome uniformity of Rauschenberg’s white panels, devoid of any kind of painterly affect, created a kind of receptive nothingness that in Cage’s mind allowed them to become landing sites for all kinds of enunciative phenomena. These mute projection screens would play the same role as Cage’s revolutionary score

for his work 4’ 33” (1952), in which three completely silent musical movements allow the world to make its own ambient music. In both of these historically pivotal works, the artists’ deployed their reductive aesthetic structures in order to frame the plenitude of the world around us. In doing so, they ushered in a revolution of meaningful nothingness that went far beyond the confines of the New York art world.

as an american who has come to know Bob l aw’s work only recently, it is hard for me not to imagine the artist sitting in the fields around st Ives in the late 1950s with sheaves of blank drawing paper – his ‘airports’ for recording what the philosopher gaston Bachelard would call the ‘intimate immensity’ of the world that surrounded him.3 Neither simply a Minimalist, nor completely grounded in the iconoclasm of Conceptualism, l aw seems to have occupied a unique middle position within the constellation of postwar international contemporary artists. although it is unclear whether or not he was consciously aware of the ground-clearing experiments of Rauschenberg and Cage, it is certain that l aw was fuelled by his own unique and enthusiastic embrace of the fecund potential of nothingness. Taking up pencil, pen and brush in the pursuit of getting ‘closer to the truth instead of the illusions’, as he put it, l aw would embark upon a parallel artistic trajectory to that of Rauschenberg, Cage and many others, in which he would become a willing participant in an oncoming revolution that would celebrate the transformative value of nothing and nowhere. 4

The irony of Fyfe Robertson’s ‘everyman’ critique of l aw’s participation in the Hayward Annual: Current British Art at the Hayward gallery, london, was the

populist television critic’s inability to see that l aw’s ‘road to nothing and nowhere’ was in fact a path marked by the artist’s fervent desire to produce something and to get somewhere – albeit with a reductive set of means. l aw was a searcher who was not only trying to find his way in the world of contemporary art but was also attempting to orient and ground himself in the world at large. In his earliest extant works such as his Field drawings, for example, the artist threw himself into the countryside around st Ives with the task of locating himself physically and psychically in the world around him, without resorting to the clichéd conventions of traditional figurative representation or the genre of landscape painting. as l aw put it in a conversation with the critic Richard Cork in 1974:

The early Field drawings were about the position of myself on the face of the earth and the environmental conditions around me: the position of the sun, the moon and the stars, the direction of the wind, the way in which the trees grew, an awareness of nature’s elements, an awareness of nature itself and my position in nature on earth in a particular position in time. I was finding myself, and the map that went with myself. I was transcribing it graphically into charts.5

Having rejected his own earlier and more conventionally figurative landscape drawings, l aw set out in 1958 to clear the ground by employing a new economy of representational means that were notational – almost hieroglyphic – markers of his phenomenological position in space and time. In order

Robert Rauschenberg

erased de Kooning Drawing 1953

Traces of drawing media on paper with label and gilded frame

Robert Rauschenberg

erased de Kooning Drawing 1953

Traces of drawing media on paper with label and gilded frame

to situate himself within the landscape of the natural world around him through the practice of drawing, he developed a set of highly reductive and formally coded ideograms that he would use repeatedly to denote the sun, the moon, clouds and trees. Comparable to the Paleolithic cave pictograms that l aw was fond of citing in his talks as the zero degree of human representation, his evolving lexicon of forms bounced around the surface of his paper from drawing to drawing depending upon the environmental factors of the particular day.

In each case, these carefully positioned icons inhabited a blank visual field delimited by a rectangular framing device that the artist drew with a single line just inside the edges of the rectangular paper. as much a proscenium as a boundary, these slightly off-kilter and unabashedly freehand framing lines would appear over and over again in these drawings. graphically reiterating the convention of the picture frame – albeit with a deliberately handmade sensibility – this conventional representational boundary had the effect of providing a provisional field of protective containment or a talisman, holding at bay the sublime terror evoked by the expansiveness of the void, whilst also emphasising the receptive emptiness of the blank piece of paper. In a sense, these framing lines became projection screens on which the intimate and transitory theatre of the everyday would play itself out. Clouds would move across his field of vision; the wind would blow; stars would make their appearance in the dusky sky; and the sun and moon would trace their celestial trajectories across the arc of the visible world. all of these movements would find themselves recorded, one after another, within the field of drawing defined by l aw’s graphite boundary and in doing so the artist would find himself.

Comparable to the compulsively repetitive and highly personal drawn notations of Conceptual artists of the 1960s – such as Hanne Darboven, whose signature collection of linear constructions of numbers, lines and markings would cover pages of graph paper in an attempt to systematically record the passage of time – l aw would execute tens of these Field drawings each day, after which he would ruthlessly edit his output and resolve upon a handful of finished works. While Darboven called herself a writer rather than an artist or a draughtsman, l aw would similarly attempt to trace his movement through space and time with his own idiosyncratic graphic vocabulary. some of these drawings included obviously erased and workedover lines, emphasising a certain ephemeral quality to his observations as if to give a knowing nod to the constantly shifting motion of the natural forces surrounding us. With their seemingly provisional execution and their serial production, l aw’s Field drawings were both acknowledging the transient nature of the world that we inhabit while also celebrating the profound uncertainty that this transience engendered. In the world of the Field drawings, tomorrow would bring another day with another set of unique conditions that would be equally beautiful and no less fleeting than those that came before. Despite their conceptual rigour and their minimal means, these drawings would paradoxically become fragile, poetic records of the passage of a highly subjective and ruthlessly personal non-historical time.

as l aw’s Field drawings progressed, they would become more and more minimal. and as they started to disappear, they would leave in their wake the ghostly emptied-out theatre of white nothingness that would

be defined by his irregular graphite passepartouts. These deceptively simple rectangles would come to be the definitive gestures of what were known as his ‘open’ drawings with everything that the term implies: an open window onto the world; open-ended meaning; open to interpretation; open for business. These works would become perfect receptors for the subjective projections of their viewers while also being antennae exquisitely tuned to the subtle vibrations of the surrounding world. While confrontational in their emptiness – as populist critics such as Robertson would gleefully point out – the inescapable humanity of their wavering lines speaks to a deeper interrogation of the world at large and the artist’s place in it. as l aw put it when discussing his drawings:

The ‘essence’ of this work is the same as in Paleolithic cave painting. The hunter artists drew the beast so that it could be seen and meditated upon when it was not actually present. In the same way we write a book or make an equation because we are not yet advanced enough to hold it in our heads. That means once you draw a line around your hand and then take your hand away the mark where your hand was exists even though your hand is no longer there. What does exist is an imprint and that is the beginning of art, in there being nothing which is something. art is the result of thousands of years of thinking how to think.6

l aw’s exposition on the origins of Paleolithic art would seem to suggest that the lines of his ‘open’ drawings were in fact summoning something rather than nothing. In this case, the something that is called into

being is the direct result of the all too human movements of the artist’s hand – or what he refers to as the artist’s ‘imprint’ – which he attributes to the foundational moment of artistic endeavour. In the case of l aw’s ‘open’ drawings, his graphite boundary would become a framing device comparable to the open structure of Cage’s score for 4’ 33” Within the confines of l aw’s lines, as with the delineating structure of Cage’s three silent movements, worlds full of multiple possibilities would emerge. This is the revolution of nothingness giving birth to a new way of seeing that did not involve representing the world but rather allowing the world to imprint itself on our individual and collective consciousness. What is contained within the boundaries of l aw’s lines in his ‘open’ drawings, or within the silent structure of Cage’s composition, was not a cynical or ironic rejection of the experience of the viewer but rather a deepening of vision in a call for a new kind of perceptual openness. standing in symbiotic relationship to l aw’s ‘open’ drawings was another group of simultaneously produced works known as his ‘closed’ or Black drawings. In these works, the same irregular linear line following the contours of the inside edge of the paper would define a field that would be completely filled with dense and feverishly rendered crosshatched pencil marks. With the artist’s hand visibly present on the surface of these works, their darkened fullness constitutes a necessary inversion of the spatial inclusiveness of his ‘open’ drawings. Maintaining the uneven and imperfect rendering of the listing internal infrastructure of his framing line, the complete overall density of the ‘closed’ drawings appears, at first glance, to close off the infinite possibilities of the ‘open’ drawings. When one looks at them, however, while taking into account the phenomenological aspect of

these works that the artist himself emphasised, one can begin to see their dark emptiness in a new light. Taken as a window or a perceptual aperture, the ‘closed’ drawings merely show the inverse of the ‘open’ drawings, in effect pointing to the diurnal rhythms of our own bodily system of perception. looking through a window after dark in order to survey the descent of night upon the landscape, we are offered up a kind of visual silence that is equally replete with possibility as the negative space of the ‘open’ drawings.

l aw would continue this pursuit of the poetic possibilities of the void, in a related body of works begun in the late 1960s that are referred to as the Black Paintings. If the blackness of his ‘closed’ drawings was frenetic and emphasised the movement of the artist’s hand through space and time, in these works l aw would try to remove his own hand from the equation as much as possible, by painstakingly depositing numerous completely uniform and affectless layers of different coloured acrylic paints in an attempt to negate any traces of his own presence. Day after day he would paint his canvases with perfectly flat monochrome coats of violet, blue, indigo, purple and black – letting each one fully dry before moving on to the next. This meticulous reapplication of paint was reminiscent of geological sedimentation. sitting one on top of the other, these painterly strata would come together to create highly complicated and richly populated versions of the colour black, giving a startlingly evocative texture and multivocal quality to the purported nothingness of the void. although l aw would go on to produce many other series of works over the course of his nearly five-decade career, it is instructive to note that this play between lightness and darkness, something and nothing, being

and the void – that was already at work in his earlier drawings – would find its continuation and culmination in a series of 14 large canvases grouped under the titles Mister Paranoia and Nothing to be Afraid of, that the artist completed between 1969 and 1972. The irregular rhomboidal framing lines that first appeared in his Field drawings – which went on to define the surfaces of his ‘open’ and ‘closed’ drawings – would then migrate onto the surfaces of these paintings, defining the picture frame along with a handwritten date in the lower righthand corner. Rendered at first with a laundry marker and then subsequently with oil paint on canvas, their scale seems to be monumental: a colossal shift up from the intimacy of his drawings. These are indeed extremely large canvases that dwarf the viewer. What is striking about them though is that there is an endearing humility in their execution that undermines any kind of heroic reading of the works.

In Mister Paranoia IV 20.11.70 (No. 95) (1970; pp.32–33), for example, its expansive dimensions (240 x 418 cm) suggest not so much a painting as a portal that could physically engulf the viewer, offering a passage to another space, time or dimension. all the while, however, these works radiate a decidedly human modesty with their assertive celebration of the handmade quality of their rendering. although they seem to mimic the imposing scale of american colour field painting that had captured l aw’s interest at the time, they shy away from the grandiose pronunciations of existential angst so dear to the purveyors of abstract expressionism.

To the contrary, these paintings emanate from a place of profound intimacy as the artist strains to find his position physically and psychically within the immensity of the world, while their titles undermine the tired

n othing to be a frai D of V 22.8.69 1969

l aundry marker on cotton duck canvas

274.3 x 213.4 cm | 108 x 84 1/8 in

Private collection

heroic narrative of postwar painting with their playful invocation of ‘paranoia’ and ‘fear’. Nothingness, the void, zero degree, null set: far from directing us to a situation of complete negativity – of paranoia and fear – these terms speak productively to the untapped potential energy radiating from l aw’s canvases and drawings. If the respiration between lightness and darkness and between nothing and something in l aw’s work suggests that a kind of Heisenbergian uncertainty is at play, we need to see this not as a problem but as a virtue.7 In his drawings and paintings, l aw submits that we are neither here nor there but somewhere in-between being and nothingness, or rather, a nothingness that is the guarantor of being. one might say that there is a quantum model at work here; a cosmological model; an anthropological model; or certainly a phenomenological model. all of these would be correct. l aw’s work is neither Minimal nor Conceptual but is, rather, open and searching. although he produced his work in the context of the revolutionary artistic upheavals of the 1950 to 70s, his journey was very much his own. In this light, we have to acknowledge that there is an obvious kernel of truth in Robertson’s criticism. l aw indeed travelled far down the road to ‘nothing and nowhere’, but what the critic failed to grasp was that this was a good thing. as Cage said in his ‘lecture on Nothing’ (1959) when referring to the resistance to his advocacy of silence and nothingness: ‘We need not fear these silences – we may love them.’8 We might say the same thing about l aw’s road to nothing and nowhere.

1 ‘Fyfe Robertson at the Hayward gallery’, Robbie, BBC 1, 15 august 1977; transcript of television interview published in Art Monthly, no.11, october 1977.

2 John Cage, ‘lecture on Nothing’ (1959), in Silence, Wesleyan university Press, Middletown, CT, 1973, p.126.

3 see gaston Bachelard, The Poetics of Space, Beacon Press, Boston, M a , 1969, p.203. The first edition of this book appeared in French in 1958, at the same time that l aw was undertaking his early Field drawings. Bachelard’s book was a ground-breaking phenomenological study of the poetic imagination. His discussion of poetic images of the immensity of the world are bound together with a consideration of the intimate space of the phenomenological subject. ‘It would seem, then, that these two kinds of space – the space of intimacy and world space – blend. When human solitude deepens, then the two immensities touch and become identical’. In one of Rilke’s letters, we see him straining toward ‘the unlimited solitude that makes a lifetime of each day, toward communion with the universe, in a word, space, the invisible space that man can live in nevertheless, and which surrounds him with countless presences.’ This seems to be an apt description of l aw’s practice as well.

4 ‘Bob l aw in conversation with Richard Cork, april 1974’, in Bob Law: 10 Black Paintings 1965–70, Museum of Modern art, oxford, 1974; reprinted in Bob Law: A Retrospective, Ridinghouse, london, 2009, p.33.

5 Ibid.

6 Bob l aw, artist’s statement first published in the catalogue for his 1967 exhibition at the grabowski gallery, london and later included as a loose-leaf insert in the artist book Bob Law: 16 Drawings that accompanied his exhibition, Bob Law: Paintings, at lisson gallery, london, in 1971. Reprinted in ibid., p.78.

7 For more on the subject, see Bob l aw, ‘The Necessity for Magic in art’, unpublished lecture at the university of sussex (1964), Bob l aw archive, london.

8 Cage, op.cit., p.109.

Drawing 29.4.59 1959

Drawing 29.4.59 1959

on the occasion of Bob Law: Field Works 1959–1999

9 october – 7 November 2015

Thomas Dane gallery

3 & 11 Duke street st James’s london sw 1 y 6 bn

united Kingdom

thomasdanegallery.com

In association with Richard saltoun gallery 111 great Titchfield street

london w 1 w 6 ry

united Kingdom richardsaltoun.com

Karsten schubert

46 lexington street

london w 1f 0 lp

united Kingdom

karstenschubert.com

Ridinghouse

46 lexington street

london w 1f 0 lp

united Kingdom ridinghouse.co.uk

Publisher: Doro globus Publishing Manager: louisa green Publishing a ssociate: Daniel griffiths Publishing a ssistant: Jay Drinkall

Distributed in the uK and europe by Cornerhouse Publications HoMe

2 Tony Wilson Place Manchester m15 4 fn united Kingdom cornerhousepublications.org

Distributed in the us by R a M Publications + Distribution, Inc. 2525 Michigan avenue Building a 2 santa Monica, ca 90404 united states rampub.com

special thanks to Vanessa and Daniel l aw, Thomas Dane, Richard saltoun, Karsten schubert, elli Resvanis, southampton City art gallery and all the lenders to the exhibition.

Copyedited by Melissa l arner

Proofread by english editions

Designed by Marit Münzberg

Printed in the Netherlands by NPN Drukkers

IsBN 978 1 909932 18 0

RICHARD SALTOUN

Karsten Schubert

all rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or any other information storage or retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher.

British library Cataloguing-in-Publication

Data: a full catalogue record of this book is available from the British library.

Images © and courtesy 2015 estate of Bob l aw, unless noted below

Text © the author

For the book in this form © Ridinghouse

Photography credits:

Bob l aw archive: pp.2, 14–15

Noah Da Costa: pp.11–12, 32–33, 37–40, 45 FXP, london: pp.19–20, 22–29, 36

Works by other artists:

Robert Rauschenberg (american, 1925–2008). © Robert Rauschenberg Foundation/DaCs, london/Vaga , New York 2015. san Fransisco Museum of Modern art. Purchase through a gift of Phyllis C Wattis: p.7

great care has been taken to identify all copyright holders correctly. In cases of errors or omissions please contact the publisher so that we can make corrections in future editions.

p.2

The artist at home, london, c.1969

pp.14–15

The artist in his studio with paintings from his series Mister Paranoia/Nothing to be afraid of (c.1969–72), c.1970