3 minute read

In Retrospect: The Artist in His Own Words

from Bruce Beasley

Bruce Beasley

When I look back on 60 plus years, I realize what a fortunate person I am to be able to spend my life engaged in one of mankind’s oldest endeavors— turning material into human feelings.

I have devoted a career to engaging in the emotional language of shape; I say the emotional language of shape, because that is what sculpture is to me. Geometry is the intellectual language of shape, and sculpture is the emotional language of shape—much the same way that acoustics is the intellectual language of sound, and music is the emotional language of sound.

I found my calling as a sculptor early. It was at Dartmouth College in 1958, and I was 19. I had been pushed by college counselors to pursue a career in rocket engineering. This was based on my having built hot rods in high school, the idea being that a rocket program was the assumed professional extrapolation for a college-bound lad who built race cars; but in truth, I was looking for a path in life for myself.

I had always built things, ever since I was just a kid, and that connection to the manual, and to the work of the hand, was deeply important to me. I had enthusiastically taken shop classes throughout junior and senior high school. These courses were considered “trade track,” even though I was officially on the college track. I saw that the world that I was expected to enter was divided into those who made things and got their hands dirty, but didn’t decide what was made, and those who were educated, wore clean clothes, and didn’t make things, but told others what to make. I didn’t like that separation of the hand and the mind, and it didn’t address another element that was missing: what I call the emotional or spiritual side. I didn’t see a place for myself in that world.

So when I discovered sculpture at 19, it was an absolute epiphany. It was the first time that the three elements of using the hand, the head, and the heart came together in one activity. There was no question about it. That was the path I was going to take.

From the beginning, I realized that I did not previsualize sculptures and I didn’t find that drawing was a way to explore sculptural ideas—it was two-dimensional and lacked the opportunity for real engagement with tangible form. I had to just start working with three-dimensional shapes directly and hope something came of it. At first, I thought that was a serious limitation. But I did find that although I did not previsualize a sculpture and had to play around with shapes to jump-start my creative process, I did have a very strong and almost physical sensation when a composition was “right.” I realized that my way of working was really a process of exploring relationships of various shapes where, along the way, I might “find a sculpture.” I consider it exploring versus preconceived creativity.

From the very beginning, I was interested in exploring arrangements of existing shapes, but I was only interested in the shapes themselves and how they interacted with each other. I was not interested in any context or feeling associated with the original use of the object. That was the genesis of the broken cast iron pieces like Horae, Tree House and Lemures (figs. 1, 2, 3).

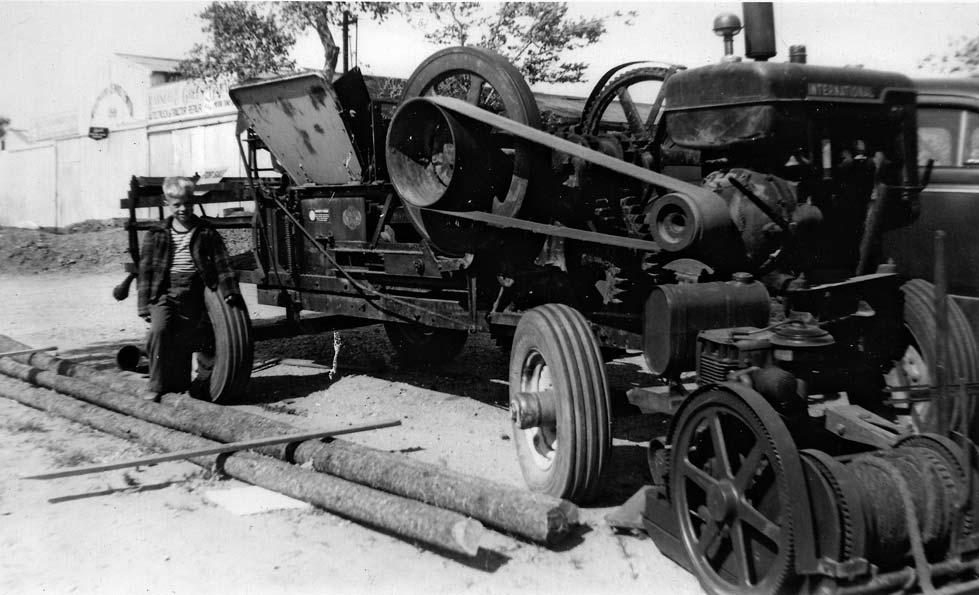

It was 1960 and I was at a scrapyard in West Oakland, where I had gone to buy some steel to make a welding table. A large pile of used, cast iron sewer pipe from dismantled houses was being broken up. I had not realized that there was a form of iron that would fracture and break rather than bend. I saw that each of those broken pieces had two voices. One was its original cast shape, which was curved and controlled, and the other was the broken edge that meandered randomly across the curved shapes. In addition, there was a color difference. The curved cast surfaces were aged and dark, while the broken edges had exposed new iron that rusted to a bright orange. It was as though the dark curved shapes were the base notes and the orange rusty edges were the high notes. Could some visual poetry result from the interplay of these two voices?

Another thing I learned from this early series was that the variety of possible arrangements I had to play around with was greatly enhanced by virtue of the pieces having been broken. A pile of broken pieces of cast iron pipe had much more potential for me than a pile of unbroken pipe. But along with the visual interest that the cast iron fragments inherently possessed was a downside, in that the thin, fragile cast iron was difficult to weld, limiting the range of possible configurations. But this was the first process of working that had resulted in sculptures that I felt were really mine, so I knew I was on to something.

The first really important exhibition I was in was The Art of Assemblage in 1961 at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. It was important to me for many reasons. This was a seminal exhibition