into the blazes of the lowest of hells, are forced to climb mountains of swords, are boiled alive in iron cauldrons, crushed between massive rocks, engulfed in the flames of burning chariots, impaled with iron spikes, bound to posts to have their tongues extracted with iron pincers, attacked by giant birds of prey, strangled by serpents, ground in mortars, and their skulls and bones winnowed like grain (fig. 3). Other scenes reveal that hell is but one of a number of possible lower realms of rebirth. Wounded men attacking each other with swords, urged on by demons with drums, gongs, and battle flags, represent the realm of fighting titans: violent beings forever engaged in warfare. Another group, with bowls of rice engulfed in flames, represents the realm of hungry ghosts whose perpetual cravings can never find satisfaction. Yet another grouping of figures, with animal bodies and human heads, represents rebirth in the animal realm. Not only hell but the entire chain of being is on display.

Whereas most of these unfortunate fates are enumer ated in Indian Buddhist texts, others have a distinctively East Asian provenance. In the lower left corner of the painting, for example, is the Blood Pool Hell to which all women, solely because they have shed menstrual blood, are condemned to suffer (fig. 4). The Blood Bowl Sutra (Japanese: Ketsubon kyō), a brief text of Chinese origin that gained wide popularity in Japan from the fifteenth century onward, states that

the blood women shed during menstruation and child birth pollutes the deity of the earth and that, further more, when they washed their polluted garments in the river, the water was gathered up by virtuous men and women and used to make tea to serve to holy men.

Fig. 3. Detail of figure 1, sinners undergoing a range of tortures in the various hells

Fig. 4. Detail of figure 1, women in the Blood Pool Hell

50

Above left: Fig. 5. Detail of figure 1, women using candle wicks to dig up bamboo shoots in the Hell for Childless Women

Above right: Fig. 6. Detail of figure 1, Datsueba taking the outer garments of the deceased by the River of Three Crossings

Because of these acts of uncleanliness, the women are now forced to undergo sufferings.7

A bamboo grove surrounds another gender-specific hell, the Hell for Childless Women, in which wives who failed to produce offspring are forced to dig up deeply rooted bamboo shoots (known as “bamboo children” in Japanese) with nothing but a limp candle wick (fig. 5). Although wives alone are condemned for this crime, the telling detail of the limp wick may suggest that a lack of children is not entirely their fault. The special condemnation of women in East Asian hells is underscored further by the scene of Maudgalyayana, the disciple of Shakyamuni (the historical buddha) foremost in supernormal powers, visiting the underworld in search of his condemned mother. Descending on a wisp of cloud, he is overcome by tears as he sees the black ened body of his mother impaled on a demon’s trident above a boiling cauldron. Unable to extinguish the sins of his mother alone, he can only improve her fate by sponsoring a ritual feast for the entire assembly of monks. It is the suffering of the damned that pays for the well-being of the monastic community.

The wizened Hag of Hell, known in Japanese as Datsueba, seated by a barren tree beside a river in Scenes of Hell and Paradise, is another female fixture of the otherworld (fig. 6). With textual and iconographic sources in Indian and Chinese traditions, the cult of Datsueba was developed fully only in Japan. She strips the dead of their outer clothing (or, in some traditions, of their skin) before they are allowed to cross the River of Three Crossings, which flows through the intermediary stage between death and rebirth. As with the Scale of Karma in Yama’s court, Datsueba weighs the clothes of the deceased to estimate the gravity of each person’s deeds. Like Yama, with whom she often is paired, Datsueba is a liminal figure at the boundary between worlds, and as such, like Yama as well, both judge and savior in the passage between life and death.

51

Michelle Yun Mapplethorpe

Michelle Yun Mapplethorpe

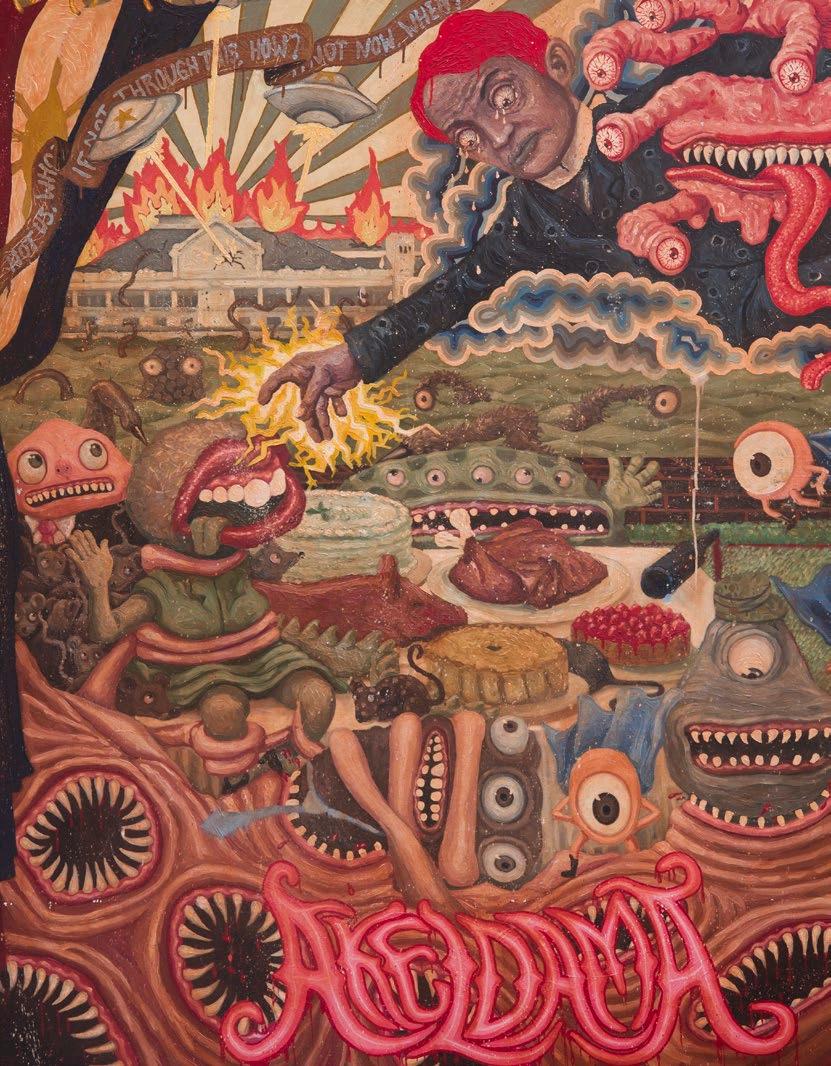

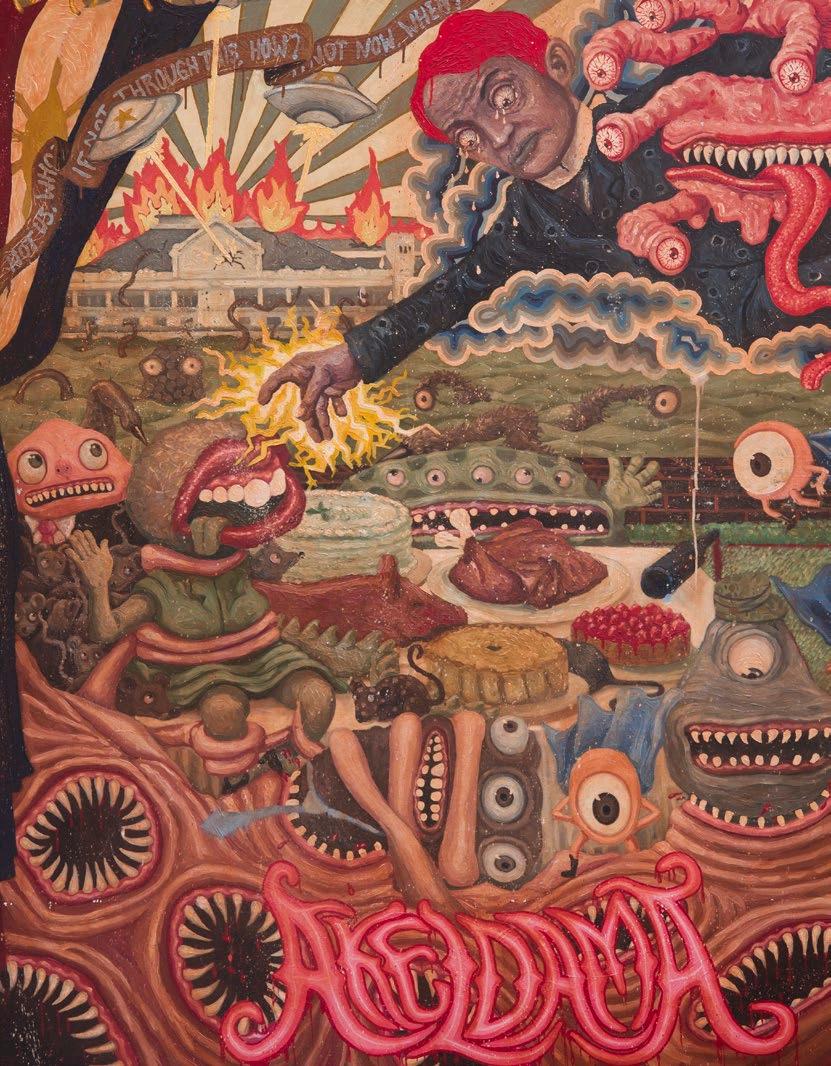

Apocalypse Now: Conceptions of Hell in Contemporary Asian Art

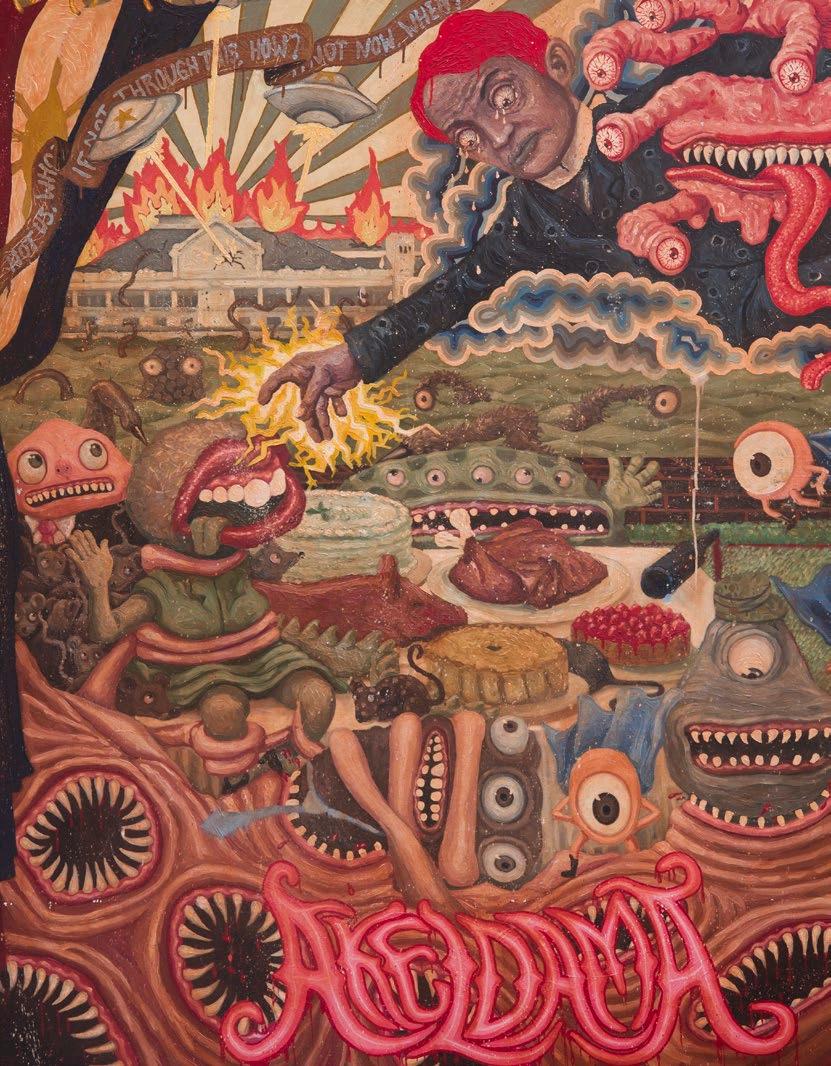

The subject of hell within the art-historical canon has served as a compelling and illustrative vehicle for conveying the consequences, often dire, of defying the religious, social, and moral standards of the time. In our contemporary moment, in which reli gious authority has yielded to secularism and social norms have become more relaxed in many urban centers, hell imagery in the visual arts has evolved to evoke war, material excess and conspicuous consumption, anthropogenic and natural disasters, and other horrific atrocities that signal to the viewer that, in fact, we are already in the midst of a self-made hell on earth. This essay will examine how contemporary artists are using their artistic platforms to create cautionary tales. Case studies from across Asia and the diaspora are used as a means to illustrate how the concept of hell has been trans posed from a punitive destination in the afterlife to a metaphor for the sociopolitical, economic, and environmental ills of contemporary society, and how the co- option of this trope reflects Asian cultures today. The detrimental physical and psychological impacts of lethal weapons like Agent Orange and the atom bomb, along with atrocities like the Sewol ferry accident (2014) and the Tōhoku earthquake and tsunami that resulted in the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear disaster (2011), have created an opportunity for Asian artists to invoke the concept of hell to encompass war, strife, and calamities both anthropogenic and environmental. Many of the artists discussed in this context merge western aesthetics and new media with traditional Asian art techniques, imag ery, and cultural connotations to deconstruct and exorcise social anxieties and shifting values relating to history, politics, identity, science, and spirituality.

Religion and Contemporary Life

By presenting concepts of hell and the afterlife through the prism of contemporary science, technology, and popular culture, artists provide insights into evolving atti tudes towards religion and divine enlightenment within twenty-first- century society. Lu Yang (born 1984) attempts to reconcile the gap between the mysticism of religious practice and rational, scientific thought. His multifaceted, multimedia practice entwines elements of Buddhism, neuroscience, gender, and physiology with pop- culture tropes including manga, science fiction, and video games as a means to deconstruct states of consciousness and enlightenment in contemporary society. Many of his works, like TMS Exorcism (2017), a video installation that alludes to disturbing historical

67

silhouette to painting edges

silhouette to painting edges

Bhavachakra (Wheel of Life) Tibet 18th century

Mineral pigments on linen, silk brocade mount H. 401/4 x W. 611/4 in. (102.2 x 61.3 cm)

Tibet House US Collection

References

Jacqueline Dunnington, The Tibetan Wheel of Existence (New York: Tibet House New York, 2000), 13, 39, 118.

Himalayan Art Resources, “Wheel of Life,” https://www .himalayanart.org/items/591 (accessed January 12, 2020).

The Bhavachakra, or Wheel of Life, is a graphic teaching device used in Buddhism, a visual representation of suffering and the escape from that suffering. The important elements of the graphic, including hell, are clearly visible in this large Tibetan example. The wrathful figure that surrounds the wheel is a personification of the cycle of rebirths, or samsara. While this figure is sometimes identified as Yama (god of the hell realms) or Mara (an evil being inhabiting the god realm) the figure is known in Tibetan Buddhist traditions as the “Demon of Impermanence.” On this specific piece, the figure tramples a human body under each foot; at the corners of the painting, near his hands and feet, are the four protectors: the dragon, snow leopard, tiger, and garuda (a mythical bird-like creature), representing the corresponding bodhisattva qualities of gentle power, clear awareness, confidence, and fearlessness. At the very center of the wheel, the three poisons circle in the form of a black pig for ignorance, a snake for anger, and a rooster for desire. The ring around this is filled with beings collecting merit (karma) and moving upward on the left, and exhausting merit and moving downward, tied together with a rope, on a black background on the right. The larger sections of the wheel are dedicated to the six realms of existence: the realm of gods, asuras (warlike demigods), humans, animals, hungry ghosts (pretas), and hell. In this Bhavachakra, each of these sections includes figures and architecture within landscape settings. The realm of pretas, to the lower right, is filled with hungry ghosts punished for their greed in past lives. Suffering perpetually from hunger and thirst, only fire passes through their lips.

Hell is designated by the wide section at the bottom of the wheel. In the upper portion of this section, Yama Dharmaraja, the Lord of the Dead and King of Judgment, grasps a stick in his right hand and holds a mirror in his left. The latter reflects the actions of those presented to him for judgment. Before him, lively, cartoonish animalheaded demons mete out the tortures of the various hells. At the center, many sad souls are boiled in a huge cauldron; others are pierced by blades protruding from a mountain, sawed in half, stabbed, and burned within the walls of the hottest hell, while some have their tongues run over by oxen pulling a plow driven by a demon.

The ring that forms the rim of the wheel consists of twelve cartouches with scenes representing the components of the doctrine of dependent origination: ignorance (a blind man guided by a stick); mental formations (a potter); consciousness based on causality (a monkey); name and form (travel in a boat); the six senses (an empty house with windows); contact (a couple about to embrace); sensation (an arrow in an eye); craving (the drinking of alcohol); grasping (a monkey picking fruit); becoming (a couple joined in intercourse); birth (a woman with her newborn child); and old age and death (a figure carrying a bundled corpse to a funeral pyre). AP

87

2

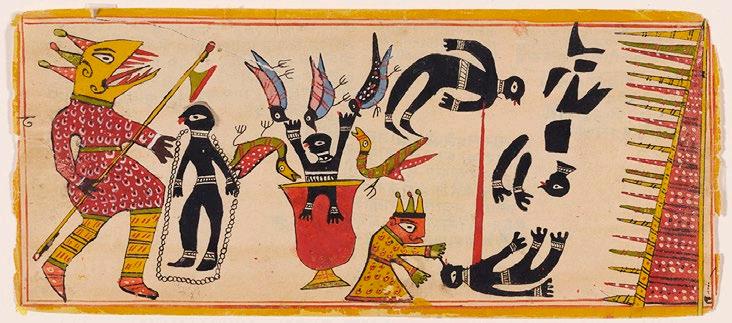

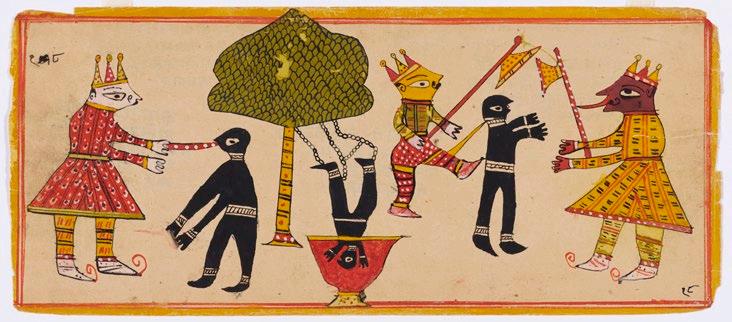

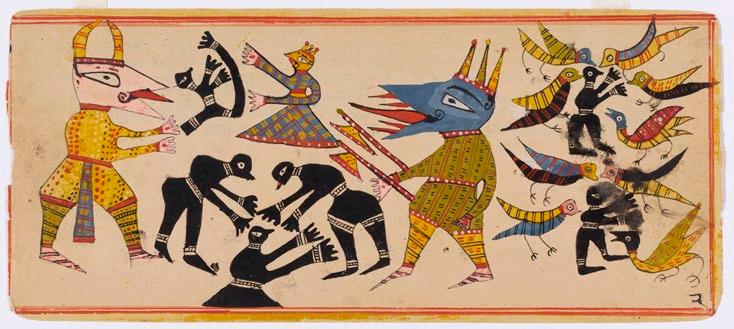

Jain Cosmological Manuscript

India, Gujarat/southwestern Rajasthan 19th century

Eight of twenty-three manuscript leaves; pigment on paper Each leaf: H. 411/16 x W. 1011/16 in. (11.9 x 27.1 cm) Museum Rietberg, Zurich, donated by Eberhard Fischer, 2014.157

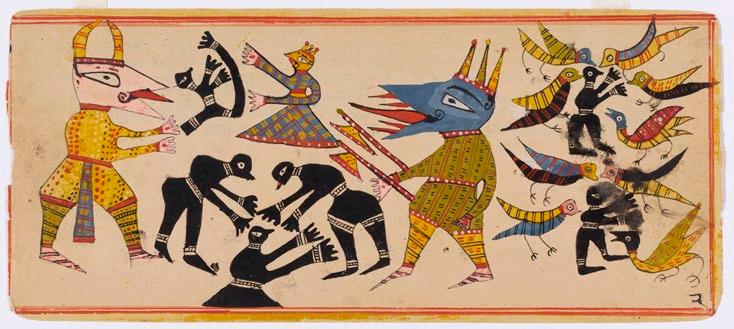

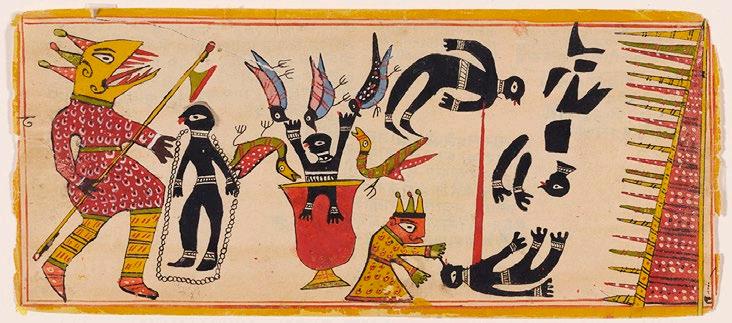

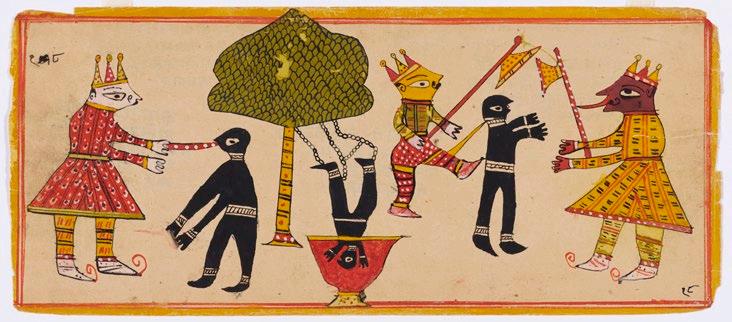

These folios in traditional loose-leaf (pothi) format illustrated with scenes of hell come from a larger group of leaves with text, now in the collection of the Museum Rietberg, Zurich. One of the folios depicts hell situated in the Jain universe, which takes an anthropomorphic form (Lokapurusha). Three planes of existence known as the Upper World, Middle World, and Lower World comprise this diagram in the form of the body of a cosmic man. All of the representations of hell in this set are painted within a yellow and red border on a blank ground. The somewhat abstract, cunning, and lively depictions appear to have been created from stencils. Shapes were outlined first and then painted in. The torturers, whether demon or animal, are enhanced with colorful, textile-like patterns. In contrast, the condemned souls are black and bound with chains around their ankles, wrists, waists, and necks. A wide range of cruelty is meted out upon the damned, from dismemberment to being cooked in cauldrons and pecked by birds. AP

References

Museum Rietberg, Kosmos. Weltentwürfe im Vergleich (Zürich: Scheidegger & Spiess, 2014), 54.

164

37

silhouette silhouette silhouette

silhouette silhouette silhouette

Enma-ō, King and Judge of Hell Japan

Muromachi period (1392–1573), 16th century

Wood with gesso and traces of polychrome, inlaid glass eyes H. 19 x W. 181/4 x D. 131/4 in. (48.3 x 46.4 x 33.7 cm) Brooklyn Museum, Gift of Mr. and Mrs. H. George Mann, 79.277

Yama, the King of Hell, is known in Japan as Enma. The influence of Chinese Buddhism, Daoism, and popular stories had transformed the Indian king of the underworld into a well-known deity in East Asia. In Japan, he is recognized individually and also as one of the Ten Kings of Hell. Wooden figures like this example often appear in temples together with sculptures of the other Kings of Hell. The traces of gesso and polychrome on this seated wooden image of Enma indicate that bright paint once adorned the figure. Enma here wears the tall hat and the long, wide-sleeved, and once- colorful robes of a Chinese judge. His furrowed brow and scowl are typical characteristics of this figure, who usually is depicted with a red face. Enma must impart penalties of harsh retribution as well as beneficent judgments. The faithful appeal to this severe figure for clemency not only for themselves but also on behalf of their recently deceased relatives. AP

References

Japanese Architecture and Art Net Users System (JAANUS), “Enmaou,” http://www.aisf.or .jp/~jaanus/deta/e/enmaou.htm (accessed April 17, 2020).

Sano et al., Heaven and Hell, 34, 81, cat. no. 28.

118

17

Lu Yang (born 1984, China) Delusional Crime and Punishment China

2016 Single-channel video with sound Duration: 14 minutes, 37 seconds Courtesy of the artist

Lu Yang was born in 1984 in Shanghai, China, where he continues to live and work. He studied under Zhang Peili at the China Academy of Art, where he received a BFA in new media in 2007 and an MFA in new media in 2010. Lu Yang’s multimedia practice explores issues related to gender, physiology, neuroscience, religion, and popular culture through the genres of gaming technology and Japanese manga popular within youth culture. The resulting pastiche of imagery and ideas attempts to reconcile the

206

55

References

1. UterusMan Game is an interac tive video game based on the adventures of the transgender superhero “UterusMan,” created by the artist, whose costume is modeled after the female uterus.

relationship between religion and rationality within contemporary society. Many of his works, like UterusMan Game (2014), have an interactive component and often intentionally push the limits of taste and social acceptability.1 Delusional Crime and Punishment is an animated video that explores existential questions about the origins of the world and the nature of divine punishment through the multifocal lens of Buddhist and Christian theology as well as science. The artist situates himself as the protagonist of a journey to the underworld that can be likened to a contemporary counterpoint to the Inferno by Dante Alighieri (1265–1321). His androgynized image first is replicated endlessly by a 3-D printer, and then shipped off to a series of torture chambers in hell. The techno-music soundtrack heightens the frenzy of the chaos and violence that ensues, while the slick graphics of Delusional Crime and Punishment con jure associations with video games found throughout popular culture. The artist’s dark humor provides keen insights into the relationship between the mysticism of religious practice and rational, scientific thought within contemporary society. MYM

207

Michelle Yun Mapplethorpe

Michelle Yun Mapplethorpe

silhouette to painting edges

silhouette to painting edges

silhouette silhouette silhouette

silhouette silhouette silhouette