fromInsideandOutside

FERRARI HAS BEEN EVER-PRESENT IN FORMULA ONE; THE only team competing today to have taken part in the first F1 World Championship in 1950. During that time, the team, its leaders and drivers have created an enduring legend and won millions of fans all over the world. But the myth has not been based on winning. Indeed, over 75 years of competition, the team has had far longer periods of not winning.

This has not, however, had a negative impact on the fortunes of the road car company, whose value as a business has soared, especially during the last 30 years, whether Ferrari was winning or not.

Nevertheless, winning is the ultimate goal of everyone who enters F1 and there is a lot of expectation heaped on Ferrari from the Italian fans, the tifosi. It takes a strong person to lead the Ferrari F1 team and to cope with the external pressures from fans and the Italian media, as well as internal pressures from shareholders. While this can manifest itself as a positive pressure, giving extra energy to the team, it can also quickly turn into something negative.

Former driver, Gerhard Berger, once said of the Ferrari F1 facility in Maranello, ‘Stand outside it and you wonder why they don’t win every race. Stand inside and you wonder how they manage to win any!’

This was in the early 1990s, the days before Jean Todt arrived, got the team organised and created a winning culture. Luca di Montezemolo brought Todt into Ferrari in 1993 after his success with Peugeot in rallying and the 24 Hours of Le Mans. During its slow decline in the 1980s, Ferrari had become a place where highly paid engineers came to boost their pension pots. It was political, and it lacked stability and a plan. Alain Prost challenged his old McLaren

rival Ayrton Senna for the World Championship in 1990; a race that ended in the famous high-speed collision at Suzuka. The following year things fell apart with Prost, who parted with the words, ‘Ferrari doesn’t deserve to win’.

Todt changed all that, but it took time. When he arrived, he realised that the structure of the company didn’t work. Having half the technical operation in the UK – one of the conditions of employment stipulated by designer John Barnard – meant that it was disconnected from Maranello in Italy. This was a problem and so Todt brought it all back together under one roof. His mission was to take the politics out of Ferrari, or at least to draw it onto himself like a lightning rod and let the team work calmly underneath him.

Under Todt, everything became joined up – the engine department was just a short corridor away from the design office and workshop, where the race chassis were built up to be shipped to Grands Prix. The sense of history was palpable, it oozed from the walls, but so did an unsettling political undercurrent.

‘At Ferrari you have a lot of people who have been around for fifty years, and they have a certain way of seeing things,’ Todt told me at the time. ‘They say things like “The engine is not good, if Ferrari were still with twelve cylinders they would win”. There are lots of rumours and inside the team there are still a few people who are not happy about the way the structure is working. And then the stories come out.

‘I like the image of an orchestra; my job is not to play the piano or the guitar. My job is to find the right people to play those instruments. And I must make sure that the pianist and the guitarist work well together. It’s a team.’

Todt created a band of brothers, brought together with a very clear goal, which was to win the World Championship for Ferrari, and each with very clear roles and responsibilities. Ross Brawn, the technical director, called it a ‘circle of fear’, in the sense that the group of leaders all relied on each other and didn’t want to let the others down, so they would always push everything to the maximum all the time.

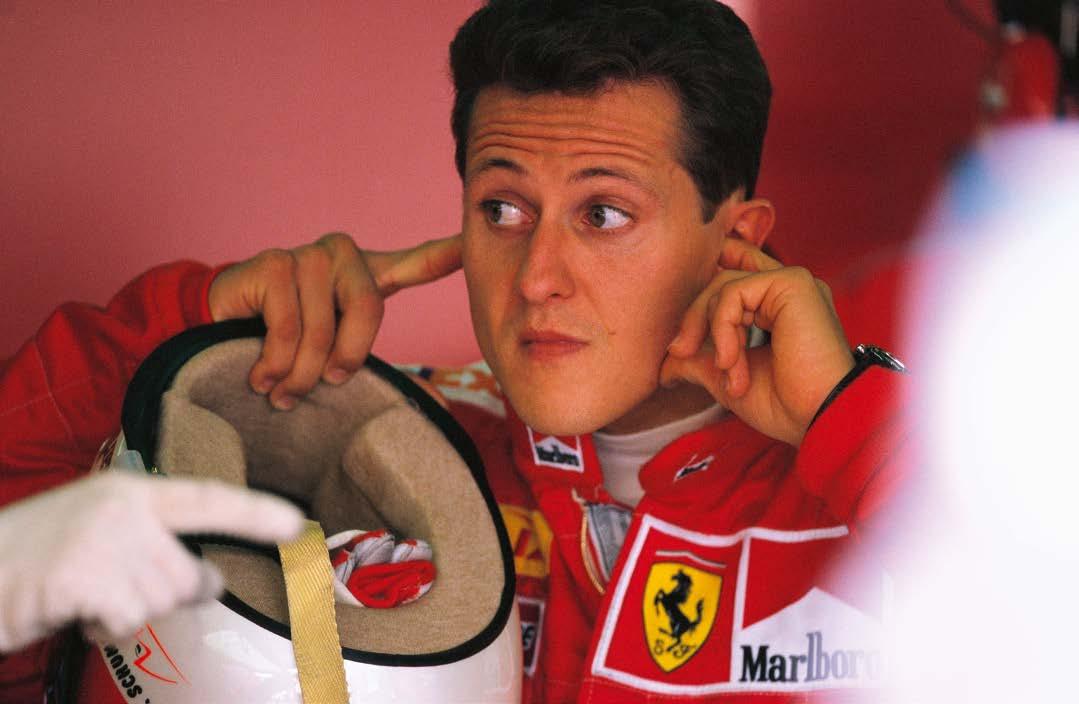

It was fascinating to go inside Ferrari and to see this in operation during that period from the late 1990s to the mid-2000s. I was fortunate to have that chance, partly through my broadcast role with ITV Sport, but mainly because I wrote two books on Schumacher and was given access by both the great German driver and the team.

This was Ferrari’s most successful period ever in F1: the Schumacher years when they won five consecutive World Drivers’ Championships and dominated the sport. It’s easy to forget that, before the first of those titles in 2000, there had been three nearmisses when they lost the title at the last gasp: against Jacques Villeneuve in 1997, Mika Häkkinen in 1998, and then in 1999 when Schumacher broke his leg mid-season and Eddie Irvine narrowly lost the title to Häkkinen.

Todt’s management style was about team unity and always being there for his people. He spent the minimum amount of time away from Maranello to attend the races or meetings, and he made sure that his people could see him when they needed to; he stayed ‘close to the problems’, so that he was able to help sort them out. ‘I have strong views and make sure that things happen,’ he said. ‘I like us to be an educated family, without being too bothered by what’s going on around.’

‘Michael is a key part of the Ferrari package in more ways than driving. He is very involved in the way the team functions’

Ross Brawn

ERCOLE COLOMBO WAS BORN IN 1944 AND GREW UP close to the Monza circuit, near Milan, the home of the Italian Grand Prix, where he still lives today. His passion for cars and racing was there from an early age, inherited from his father. Wanting to find a way to work full time in the sport, he began taking photographs in his spare time while holding down a job in commerce. Like Rainer Schlegelmilch, he began photographing in the 1960s and has attended over 700 Grands Prix. For decades he was known as the leader of the Italian contingent of photographers in Formula One and for many years was Ferrari’s official photographer, ‘the insider’, capturing key events and behind-the-scenes moments of the Scuderia.

My first experience of Ferrari was as a child, as a fan. My father was a great motorsport enthusiast, so I used to go with him and see a lot of motor races. He would point out the great drivers, like Ascari and Fangio. To me, they were immense heroes. And then naturally there was the red Ferrari, and the passion just went up to the highest level!

I remember once seeing two Grands Prix on consecutive weekends – F1 and motorbikes! That was very exciting for us kids who lived close to the Monza racetrack, and it was all we talked about at school.

Then, as time went by, I grew up and began going alone to the Monza circuit. Because I went frequently, I started to get to know all the people there. In 1961, in order to get closer to the cars on the race track, I volunteered as a marshal. We had a small team at each corner, and everyone had their roles. We had a stretcher in case a driver was injured, and I was one of the stretcher-bearers. It was in the days when there was still banking at Monza. On race day I was stationed on the banking, and I will never forget the magnificent view of the cars at full speed, up above my head! We were not far from the Parabolica corner. Tragically that was the year when there was the terrible accident which killed Wolfgang von Trips in the Ferrari at Parabolica. Luckily, we were not called on to attend to the accident.

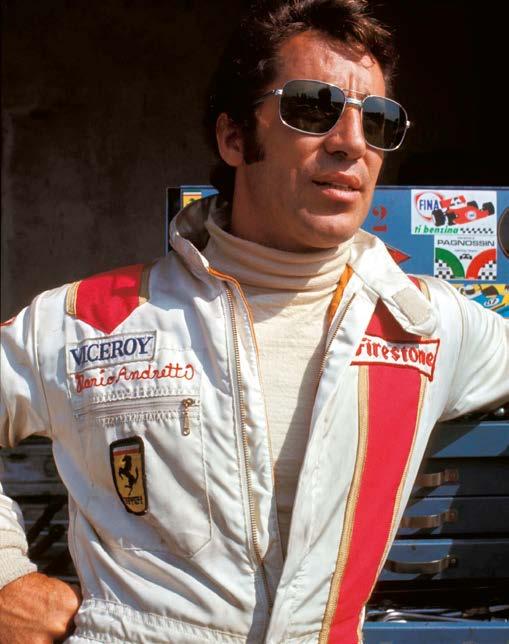

Gradually, I got to know the mechanics and engineers at Ferrari, and at the same time I got very interested in photography. I started taking photos of the races at Monza and I managed to get passes from the Monza Press Officer as I was pretty good at taking pictures. It grew from there and I started travelling around Europe. I got a contract with Beta, one of the sponsors of Vittorio Brambilla, a local guy who raced in F1 in the early 1970s, and that was the key to me quitting my day job in commerce and becoming a professional motorsport photographer. I started travelling beyond Europe to Brazil, South Africa and other countries. I was at the famous 1976 F1 season finale in Fuji, Japan, with Niki Lauda in the Ferrari and James Hunt in the McLaren. I picked up lots of contracts, for sponsors and for publications like Gazzetta dello Sport and for Ferrari. They used my images for all their publications, for books and so on.

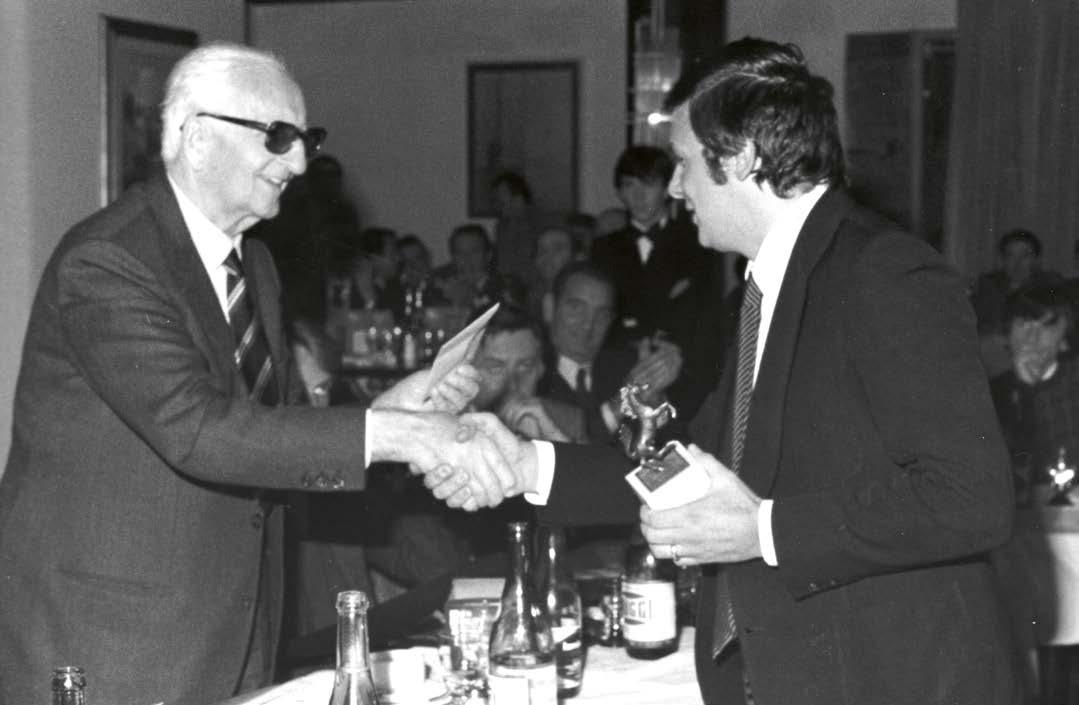

My first meeting with Enzo was like meeting a god. Gradually we got to know each other, and he liked looking through my photos. In 1977, he created a journalism prize named after his late son, Dino. There was one category for journalists and one for photographers.

In 1979, the year of Jody Scheckter’s World Championship, I won the prize. I had lunch with Enzo and after that I was brought closer on a professional level and photographed the key events, the behind-thescenes moments.

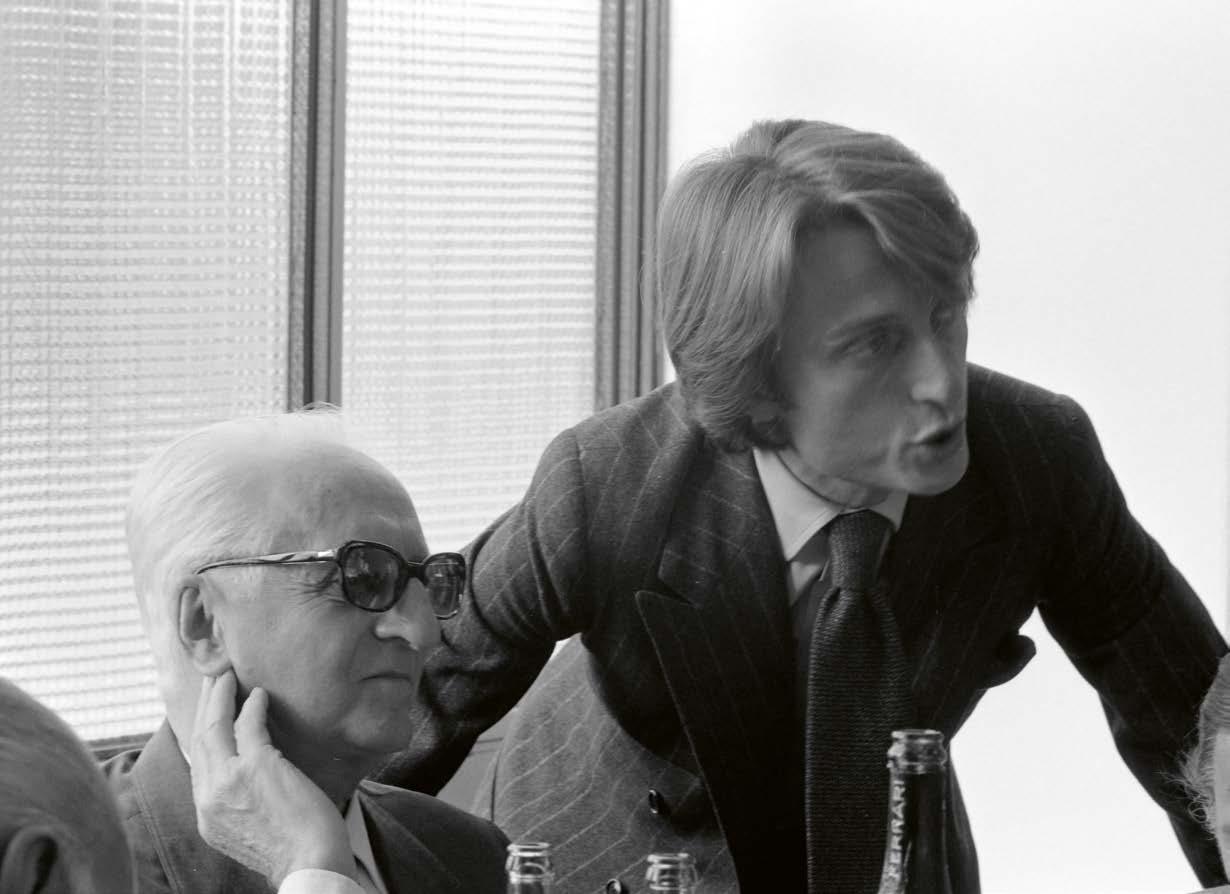

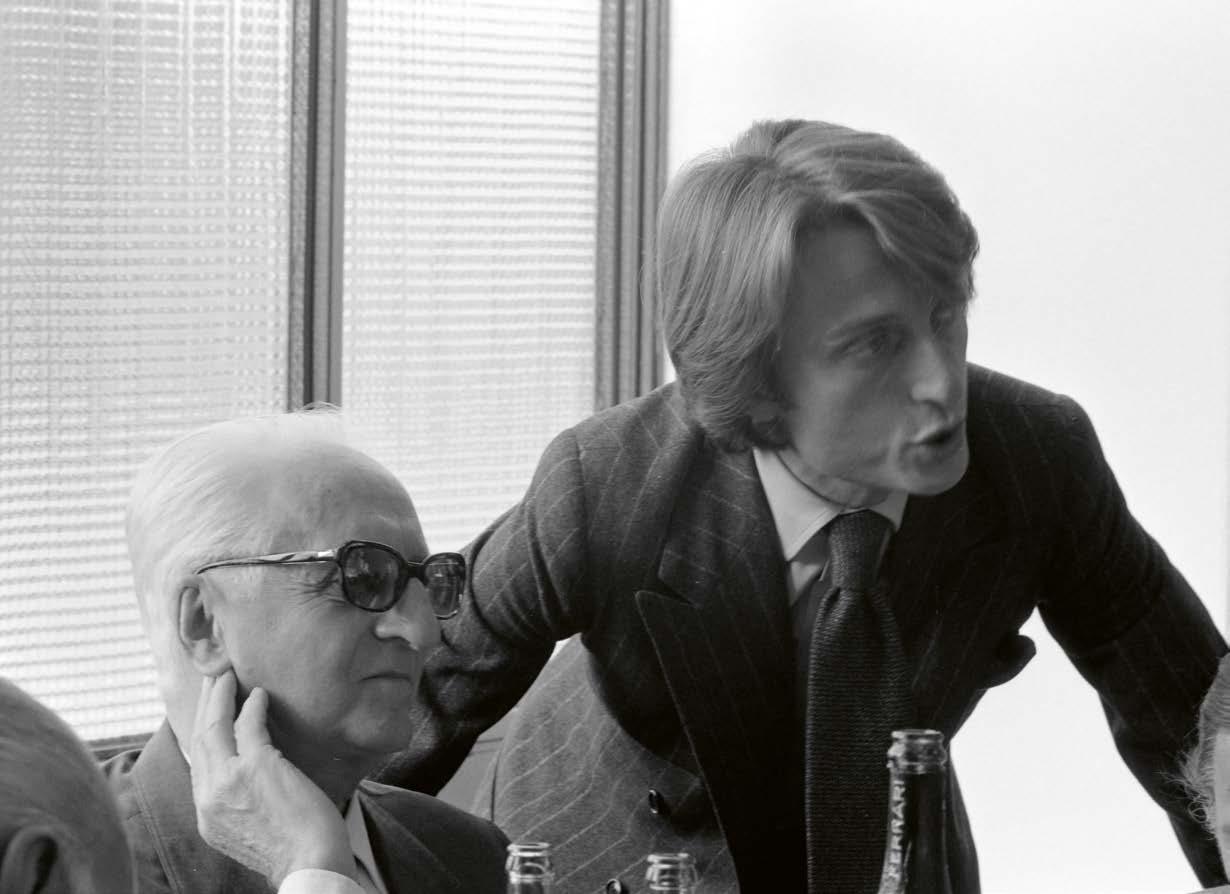

When he did his press conferences, I had to take great care. The Commendatore had a problem with his eyes, with bright light, which is why he wore dark glasses. In those days when we shot on film, to get a good interior shot you needed to use a flash. Alongside me there might be two or three agency photographers and when a flash would go off Enzo would say, ‘Colombo, no flash!’

These press conferences were a real show. Enzo was always ready with a line – he had an answer for everything. A journalist would ask, ‘Ingegnere, how much budget has FIAT given you for this season?’ Enzo would say, ‘I tell you what: take a day off tomorrow, go up to the head of finance at FIAT in Turin and ask for the budget sheet’. He hammered everyone!

‘my first meeting with enzo was like meeting a god’

professional side, I think that, in the history of modern F1, they have an important role and an important position.

When people ask, ‘What is it like inside Ferrari?’ it is quite difficult to describe because there are a lot of ingredients; it is like a painting with different faces. Ferrari has had the colour red since the beginning, even though it is not the national colour of an Italian team. Red means a lot of emotion and Ferrari has always been careful to maintain it – maybe it is the only car in competition that has always had the same colour. The red should be a little bit different, but always red. So, there is a history of great passion, starting from an idea, from a piece of paper, from the grassroots. Another element is that Ferrari is a mix of elegance and design. A car like a GTO, maybe the most expensive car in the world, is a mix of elegance and exclusivity. Enzo Ferrari was always able to build up his myth through exclusivity, creating fewer cars than the demand. You have to wait to get a Ferrari because they avoid producing too many cars.

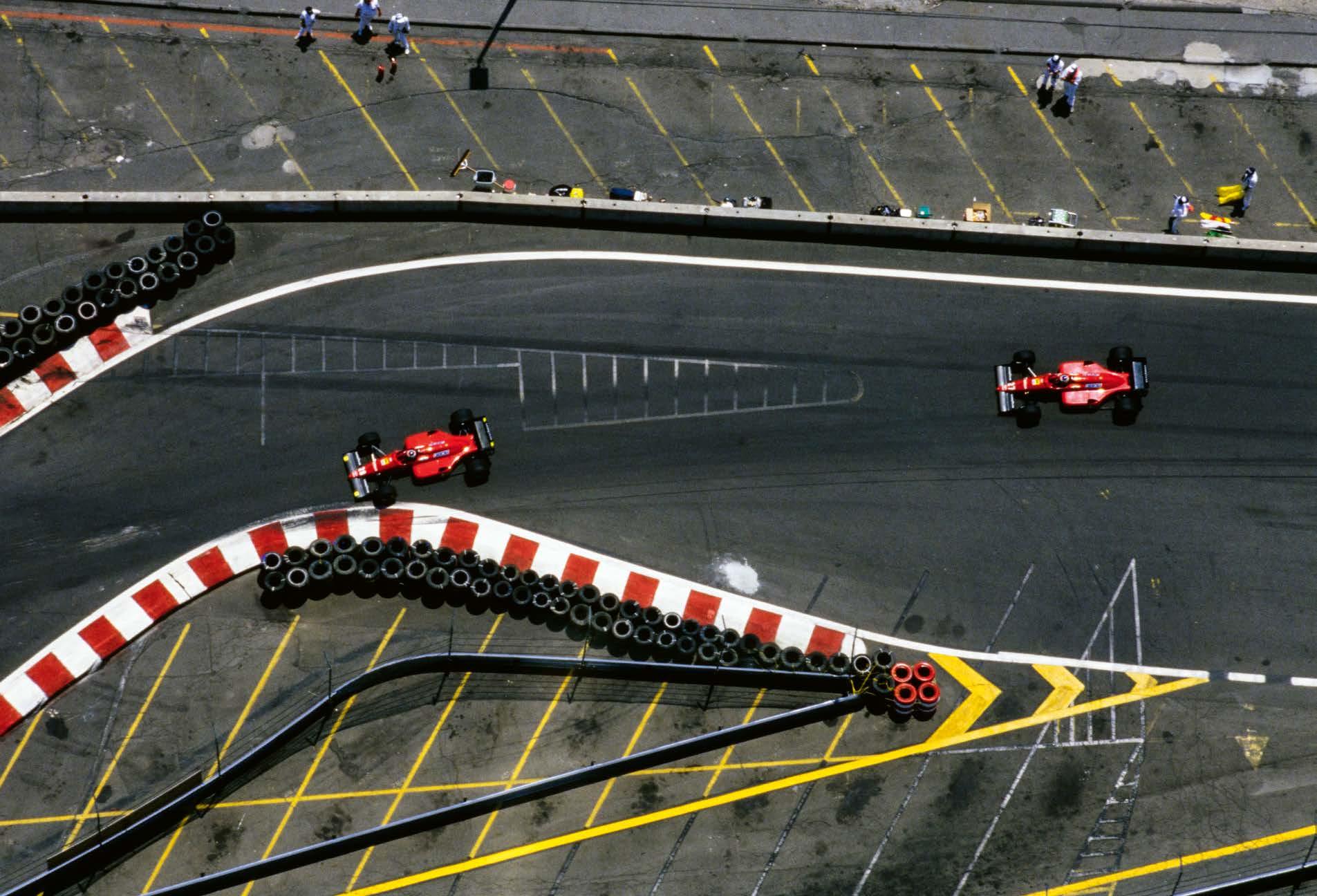

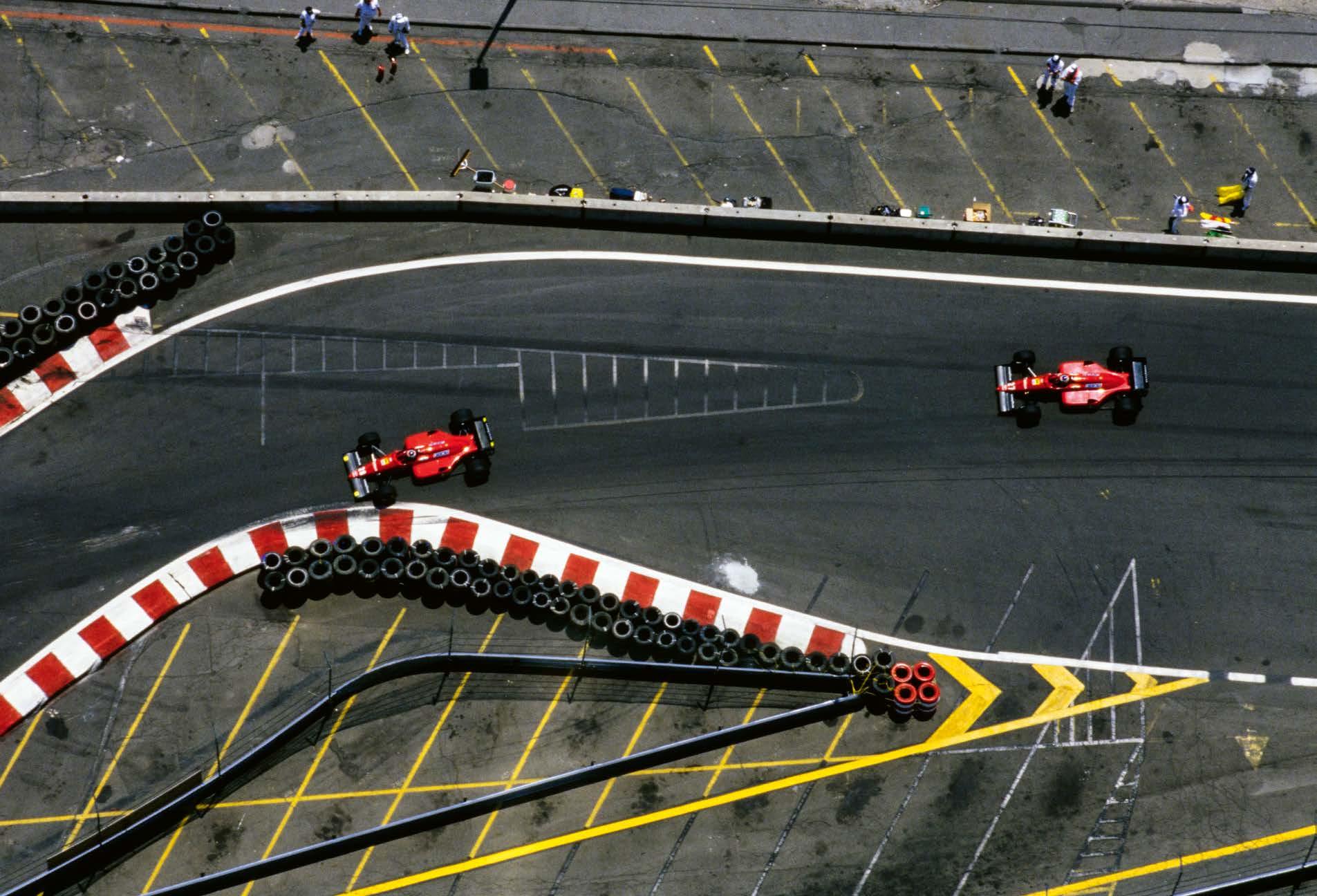

Then there is a mix of heritage, history and future. If you look at Ferrari, not only in my time, but also in Enzo’s time, we were able to build very innovative cars. We were the first to put a semi-automatic gearbox in F1 cars and road cars. So, there has always been a mix of innovation, looking ahead in terms of technology, and maintaining a strong link with the history of the key elements of the past.

Ferrari has been in F1 as a team since the beginning: in the good and in the bad moments, in the victories and the defeats, in the tragedies and in the happy times. I always say that, without F1, Ferrari is not Ferrari. But to be honest, F1 without Ferrari is not F1. So there has been a strong link since the beginning. There has also always been a special relationship between Ferrari and the tifosi, and not only in Italy. I was always impressed when the tracks in Canada or Australia were full of red flags.

At the first Grand Prix in China, in Shanghai 2004, we won with Rubens Barrichello and the team said to me, ‘Mr President, you have to go on the podium’. I had never been on the podium in my life. They pushed me so I went up and the spray of Champagne was everywhere, and Barrichello said to me, ‘Mr President, this is the first time in my life that I take a shower with a man’ and I said, ‘Listen, it is the same for me, don’t be worried!’ And looking out I was astonished to see a lot of red flags across the circuit. I was impressed because that was the first F1 race in the history of China.

One of the best moments, not only of my professional career but of my life, was when, in September 1975, we won the Grand Prix in Monza with Clay Regazzoni in front of the Italian people. At the same time, we clinched the World Championship title with Niki Lauda, 12 years after the last title with John Surtees. Not only Monza, but the whole of Italy had a huge party. Then, when we won the Championship with Michael Schumacher in October 2000 in Japan after a 21-year drought since Jody Scheckter won it in 1979, everybody was so happy. We then won five World Championships in a row. We were under a lot of pressure because, when you win, you are obliged to win again. It is a good pressure, though. Put yourself in my position: I arrived back at Ferrari at the end of 1991, and we didn’t win the World Championship for manufacturers until 1999. So, every single year from 1993 until 1997, the year of the crash between Michael and Villeneuve in the last race, I had to explain to the team and to everyone outside of Ferrari, ‘Watch out, we are working hard. Next year will be better, be patient’. Every year we did a better season than the previous one, and, despite the fact that Michael was not able to participate in a few races in 1999, we won the Manufacturers’ Championship. Eddie Irvine – nice guy, good driver but not a super driver – had the chance to become World Champion in the last race. He was up against Mika Häkkinen but just lost out by two points.

In my time, both as team manager and as chairman and CEO, we lost a lot of Championships at the last race. There was Watkins Glen with Regazzoni in 1974 and Fuji with Niki Lauda in 1977. But in F1 history, I’ve never seen something so unique as the race at José Carlos

‘enzoRIGHT: Enzo Ferrari with Luca di Montezemolo during the Ferrari 312 T2 launch on Saturday 25 October 1975 at Fiorano Circuit, Italy. (Colombo)

Ferrari is the beating heart of Formula 1. Its founder, Enzo Ferrari, was born on the racetrack as a competition driver before he became a creator of mythical road cars. No other F1 team can inspire the passion or match the stories of triumph and tragedy. Ferrari: From Inside and Outside, written and edited by internationally celebrated Formula 1 commentator, James Allen, brings together two of F1’s legendary photographers, insider Ercole Colombo and outsider Rainer Schlegelmilch. With their amazing access inside the Scuderia, their iconic images from the 1960s are presented here combined with the words of Ferrari leaders, such as Piero Ferrari, Luca di Montezemolo, Stefano Domenicali, Jean Todt and legendary designer Mauro Forghieri. The result is a stunning anthology of first-hand accounts married with superb images of F1’s oldest and most successful racing team.

“My first meeting with Enzo was like meeting a god.” Ercole Colombo

“I hid myself behind the camera. I was looking for people who didn’t see me; these were the best pictures.” Rainer Schlegelmilch