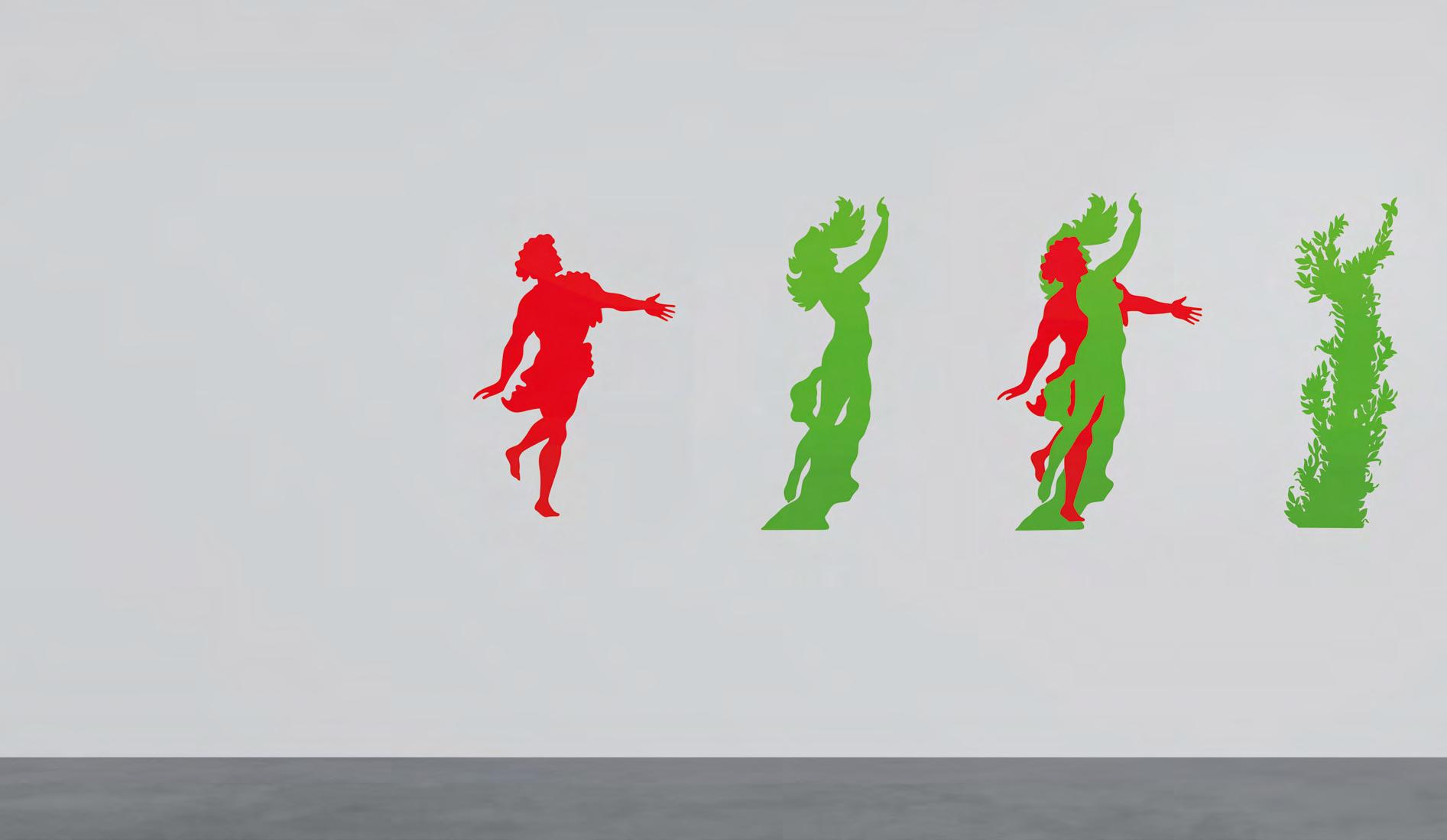

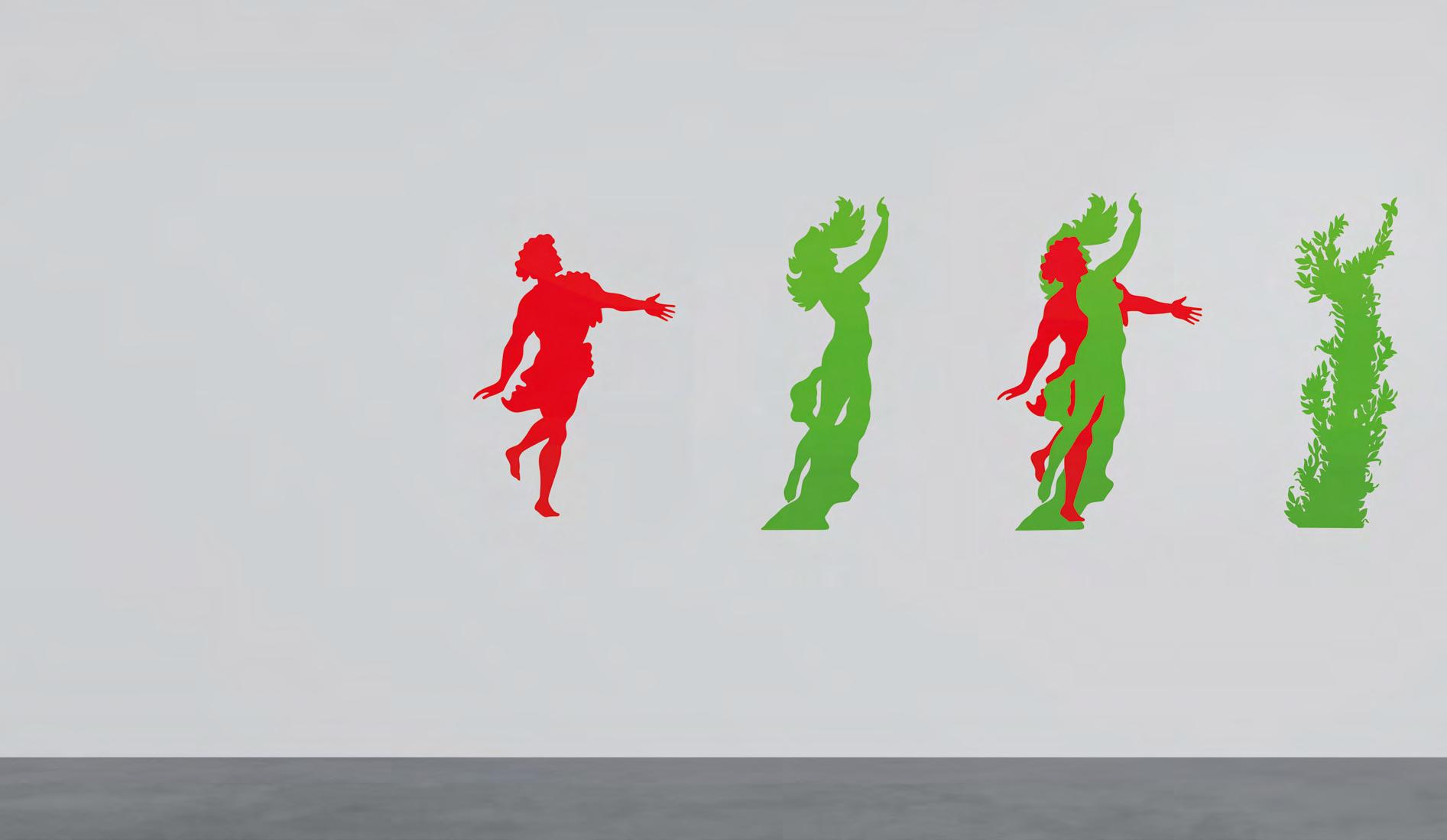

APOLLO AND DAPHNE

[6] Ovid, in his The Metamorphoses , tells the story of the god Apollo’s pursuit of the nymph Daphne and of how she escaped him by being turned into a tree. Invoking a passage in which the English writer Walter Pater muses on the theme of a Northern or ‘Hyperborean’ Apollo, Finlay has sometimes identified Apollo with Saint-Just – in which case Daphne must here be understood as representing the Ideal Republic sought by the Jacobins, eluding the Revolutionaries by returning to Nature. As Finlay has elsewhere pointed out, Saint-Just was always painted or drawn with dark or chestnut-coloured hair, while he is most frequently remembered as being strikingly blond. Ian Hamilton Finlay

THE REVOLUTION

[ 24] ‘The Revolution is frozen – all principles are weakened –there remain only red bonnets worn by intrigue.’ The waves in the rye grass never reach the shore. Saint-Just, Ian Hamilton Finlay

A work composed of ‘ad hoc’ elements – the prefabricated Corinthian capital, the corrugated iron [ whose undulations pun on classical fluting ] and the lettering which suggests both a classical inscription and modern urban graffiti. The text derives from a speech by Saint-Just – but how apt it is today after the collapse of the regimes in the East.

Ian Hamilton Finlay

In the case of THE REVOLUTION IS FROZEN ... there is a very good quotation from Hegel which I would [ likewise ] like to be added to the listing of that work. Thus, “While Religion normally involves independence of that which is essentially a mere outward and material object – a mere thing – that kind of religion which is now under consideration, finds no satisfaction in being brought into connection with the Beautiful: the coarsest, ugliest, poorest representation will suit its purposes equally well ...” Hegel, Philosophy of History. Ian Hamilton Finlay [ letter to Fiona Pearson ]

THE NAME OF THE BOW Heraclitean Variations

[32 ] A homograph that’s not a homophone; this heteronymic pun in Heraclitus: the Greek word bios means both ‘life’ and ‘bow’. Jokes, like poems, can lose a good deal in translation. Finlay’s bow-and-arrow abridges the wit of the pun to an image, but one composed precisely of those terms in which the pun is made: a solution both ingenious and amusing. Polysemy serves to illustrate the Heraclitean ‘unity of opposites’. Life, it turns out, is a labour of death: the singular arrow of semantic meaning flies in two opposed directions. But this contrariety consists in, and emerges from, the one word bios: divergence is in fact identity.

Naming what we see, the fine curve of Finlay’s bow, at rest while in tension, recalls the philosopher’s doctrine of flow.

As to how we see, the eye is first attracted by what the mind reads left-to-right: the horizontal axis of the Heraclitean vision – a world of violent swings and anxious energies –inscribed with brutal candour in the arrow’s ‘work’. Patrick Duncombe

[ 87 ] The series of white stone reliefs to which these two works belong may be seen as a discrete homage and corrective to Ben Nicholson’s iconic British Modernism of the 1930 s and onwards. In contrast to the orthogonal texture of Nicholson’s reliefs, diagonals in the spirit of van Doesburg’s CounterCompositions predominate, while the stone slabs have irregular edges. Nor are these reliefs animated by a material, post-Cubist play of light and shadow. If bold letters and numbers evoke modernist Purism, their coded triangles are sails, notionally driven by wind over an irregularly bounded expanse of water. In Rapel , Finlay’s first collection of Concrete poetry, Suprematism vied with Fauvism. In these reliefs, the cosmological correspondence of land and sea typical of the poet’s Fauvist inspiration gives way to a visual rhyme that perfectly balances the domain of sensation with formalistic austerity, in a singular triumph of a master’s late style.

[ 94 ] Finials of this type are ornamental architectural devices originally designed to flank, in pairs, the entrance to a manor house or a parkland or a garden path. Traditionally symbolic of welcome, fecundity and power, their function is poetic – or metaphorical – rather than utilitarian. These five finials, the first four of which are customary shapes, exhibit a progression from abstract to naturalistic, from less to more articulated: perfect sphere, Vanbrugh-ian ball [ sliced by a square through its middle ] , simplified acorn, full-bodied pinecone/pineapple and, shockingly, grenade. The last stage in the metamorphosis, though wholly unexpected, is both formally and verbally consistent. Finlay puns upon the covert meanings of the two words pineapple – slang for hand grenade – and grenade – a now obsolete term for the pomegranate fruit – to achieve an aggressive reinvention of the finial form and its meanings. We are now not so much invited to enter as to be ware if we do.

Prudence Carlson