Artists on the Indian Subcontinent maintain some of the world’s most ancient and illustrious textile traditions. Generations of cultivators, weavers, dyers, printers and embroiderers have ingeniously harnessed the region’s rich natural resources to create a remarkable range of ne fabrics. Showcasing over one hundred and fty masterworks dating from the ninth to the early twentieth centuries, this book celebrates Indian artists’ extraordinary achievements in textile production and design.1 Spanning time, region, technique and levels of patronage, these fabrics are arranged in three thematic sections that correspond to the predominant ornamental elements traditionally used by Indian textile makers: abstract, oral and gurative. From simply woven stripes and checks to complex narrative scenes requiring many skilled specialists, the designs on these textiles could impart color and beauty, communicate personal and group identity, express deeply felt spiritual beliefs, or render fabrics appropriate for a particular person, place, occasion or consumer market. This design-focused interpretive approach provides a fresh perspective on Indian textiles by highlighting the technical and aesthetic virtuosity of their creators as well as the social, cultural, economic and political contexts that informed their design choices.

The textiles presented in this book and accompanying exhibition were chosen from the collections of London-based Karun Thakar, who has assembled an internationally signi cant private collection of South Asian textiles, and the George Washington University Museum and The Textile Museum in Washington, D.C. The Textile Museum’s founder, George Hewitt Myers (1875–1957), maintained a strong interest in Indian textiles and built a remarkable core collection. From the 1920s through to the 1950s, Myers collected a wide range of Indian material, including sumptuous Mughal courtly fabrics ( g.2), double ikats, Kashmiri tapestry weaves ( g.4), and Mughal rugs and rug fragments. Starting in the 1930s, Myers began to purchase fragments of stamped and resistdyed Indian trade cloth uncovered in Egypt. Often referred to as "Fustat" textiles, because they rst came to light in Egypt and were originally thought to come from the archaeological site of al-Fustat, this group of trade textiles includes some of the oldest surviving examples of Indian cloth. Myers acquired more than one hundred and eighty of these fragments for The Textile Museum collection and donated fourteen examples to the Calico Museum in Ahmedabad.

Since the time of George Hewitt Myers, collecting and scholarship have steadily strengthened The Textile Museum’s South Asian collection, thanks in particular to Mattiebelle

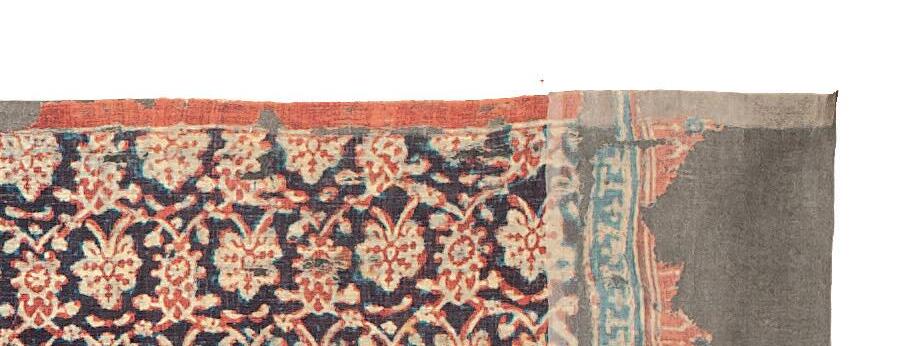

Detail of cat.131

Fragment

Silk, woven velvet

Mughal period, 17th century

The Textile Museum

3.170

Acquired by George Hewitt Myers in 1931

1 The textiles selected for this book and exhibition project were created before partition in 1947, so in the following pages the term "India" refers to the undivided Subcontinent.

Abstract and geometric patterns based on straight lines are inherent in all textiles from the moment they are created. Vertical stripes, horizontal bands and checks formed when bands and stripes intersect are the most basic of all textile patterns, created as an integral part of the weaving process itself. They only become “designs” when the warps and wefts are given colors and a choice is made by the weaver as to how these colors should be arranged on the loom as warps or woven in as wefts. Warp stripes, weft bands and checks can be woven on the most basic of looms, such as the backstrap or loin loom used by tribal groups such as the Nagas of Northeast India or the Kondhs of Odisha, and these linear designs are used to dramatic e ect in tribal weavings (see cat.1). These may be embellished by embroidering human or animal gures onto the cloth (cat.6), but the ground fabric uses stripes as its main design. Basic stripes and checks are not found only in tribal weaving: the same format can be used very e ectively for an urban or even courtly clientele when ner materials are used (cat.18). These fabrics would be woven on a pit loom, the ubiquitous loom found throughout South

Asia which, by the addition of heddles raised by means of foot pedals, permitted a much wider range of weaves than the backstrap loom.

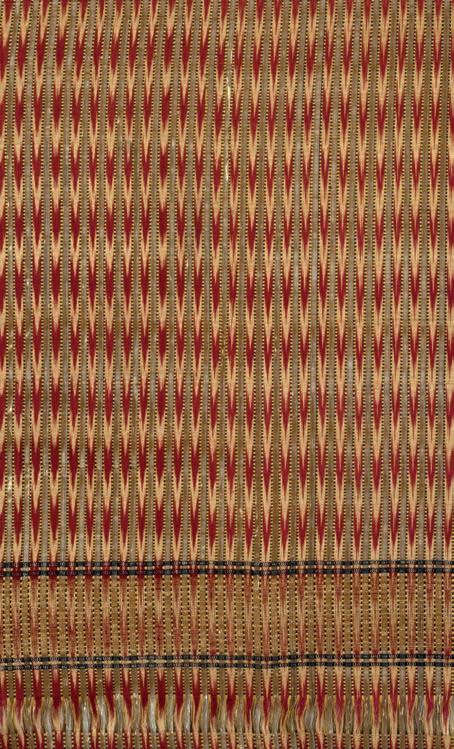

Abstract designs are also created by weaving techniques such as double-cloth, as seen in the domestic multi-purpose khes of Sindh ( g.1): here, the double-cloth weave has no right or wrong side, and allows the two-colored pattern to appear perfectly in reverse on either side of the cloth. Designs and patterns do not need to be in contrasting colors to be e ective: subtle monochrome patterns in zigzag and diamond shapes are created when woven in the herringbone and diamond twill techniques, and are frequently used for plain woolen and pashmina (goat-hair) shawls and blankets.1 Using di erent weaves in monochrome abstract designs can give remarkably e ective visual and textural variety to the humblest of fabrics: utilitarian cotton towels, for example, need an uneven surface to dry e ectively. While today these are most often created with looped pile or a wa e weave, in nineteenth-century India an inventive range of extended plain-weaves was used to achieve a visually interesting raised surface.2 Woven abstract patterns can also be formed by varying the numbers and relationships of warp and weft threads: even in plain-weave, wefts may be paired, or made of thicker thread, to form dominant horizontal bands (cat.19); warp threads may be grouped with spaces in-between to leave regular square gaps in the fabric;3 satin and twill weaves may use di erent ratios of warps to weft threads to create a variety of surface e ects, as in mashru (cat.2) and Kashmir shawls (cat.67).

Length of khes, domestic furnishing fabric or bedding

Cotton, double weave

Sindh, Pakistan, ca.1880

Victoria and Albert Museum

IS 210-1883

© Victoria and Albert Museum, London

The inevitability of creating stripes and bands in woven textiles means that these, unsurprisingly, occur in the oldest textiles known from South Asia. No very early textiles have survived in India itself, although archaeological nds suggest that striped, checked and other geometric designs were known as early as the Harappan period (ca. third millennium bce), at which time utilitarian ceramics and architecture were also being decorated in linear abstract patterns.4 Areas to which Indian textiles were exported in earlier times have yielded a few rare pieces of evidence for textile production and trade. One of the earliest known Indian textiles to have come to light so far is part of a woolen blanket or rug excavated at the Central Asian site of Niya ( g.2), which uses a simple geometric design of stripes and crosses in its tapestry-woven design.5 In tapestry weaving, weft threads are woven as isolated pattern motifs rather than being carried across the whole width of the textile and emerging onto the surface as the design requires. The tapestry technique results in a linear, often stepped, design which becomes exaggerated when the bers are relatively thick, as they are in g.2, in contrast to the curvilinear patterns made possible by sophisticated draw-loom weaves and the use of ner thread.

The earliest known piece of Indian woven silk to survive, excavated at Deir ‘Ain ‘Abata in Jordan, uses warp stripes coupled with abstract warp-ikat designs.6 These fragments, dating from the seventh to eighth century ce, are attributed to India mainly because they are made of tasar silk (sometimes

anglicised to “tussar”), one of India’s so-called “wild” silks, which are the indigenous strains of silk rather than the ner Bombyx mori or mulberry silk, which was introduced into India from China. Indian cotton warp-ikat textiles of similar date (seventh-ninth centuries ce) have also been found at Nahal Omer in Israel ( g.3).7 The ikat technique has a long history in India, and lends itself especially well to linear, abstract patterns like arrowheads and chevrons ( g.4), as well as simple streaks or blocks of undyed yarn arranged against the dyed ground of the textile.8 However unassuming these designs may appear, the placing of these small undyed blocks of weft threads within the woven textile takes skill in weaving and in design – the ikat streaks must appear exactly in the center of the woven grid pattern if the design is to succeed. Vertical ikat streaks or arrowheads are formed by wrapping resist material around the warp threads, to leave small undyed areas after the whole hank of yarn has been dyed. These are then manipulated into a V shape which is set up on the loom and woven, forming the distinctive streaky patterns shown not only in the fragments found in Jordan and Israel ( g.3) but also even earlier in the Ajanta paintings of the fth century ce 9 The paintings at Ajanta are our most important source of information about many aspects of life in fth-century India, including the patterns on textiles and how they were used. It is noticeable that the majority of the textile patterns shown at Ajanta are geometric or abstract, in stripes, checks, ikat patterns or dots, rather than oral or with bird or animal patterns, which only occur in very few places (see Floral Patterns, p.140).10

Wool, plain-weave and tapestry weave

North India, ca.1st century ce

British Museum 1907.1111.105

Fragment of cotton with warp ikat design excavated at Nahal Omer, Israel

India, 7th-9th century ce

© Israel Antiquities Authority, photo: Clara Amit

Length of ikat fabric (detail)

Silk, with silver-gilt metal strips, warp-ikat dyed Probably Hyderabad, Telangana, early 19th century

Victoria and Albert Museum IS 4-1999, Given by Mr and Mrs Praful Shah

© Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Hazara region, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province, Pakistan, 19th century

Cotton plain-weave ground embroidered with oss silk thread in surface darning stitch. Four panels stitched together

L 254 cm x W 142 cm (100 in x 56 in)

Karun Thakar Collection, London

This piece and cat.4 are unusual for their striped designs, resembling woven fabric such as mashru (cat.2).

Embroideries from the Hazara region more often have repeating patterns of diamonds or stylized owers (cat.87). This type of textile, in which the whole surface is covered with oss silk embroidery, is known as bagh (literally meaning “garden”). Baghs embroidered in dark pink and green oss silk on a white cotton ground are sometimes called thirma bagh; they were made in the region of Hazara in Pakistan, just north of the border with Pakistan’s Punjab province. A brighter pink is popular in the adjacent district of Swat (see cat.39), where the darning stitch used in these baghs is also prevalent. This type of embroidery, which uses surface darning stitch in oss silk worked from the back of the fabric, extends over a large geographical area, from the soof embroidery of Sindh (see g.12, p.28), through the phulkari of Punjab (cat.14, 38) to northern Pakistan (cat.37, 42).

Previously unpublished.

Abstract Patterns

17.

Indus Kohistan, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan, 20th century

Cotton plain-weave ground, silk thread embroidered in tent stitch and brick stitch, with glass beads and added printed cotton top borders

Max L 14 cm x Max W 15 cm (5½ in x 6 in)

The designs found on these ve small bags – continuous rows of chevrons alternating in color after every row, elongated swastikas, and o set double diamonds – were produced by embroidering minute rows of counted thread tent stitches, enhanced by separate clustered and dangling glass beads. All ve bags were most probably produced in Indus Kohistan, but because of their material content, visual similarities and common repertoire of stitches, it is also possible that one or more could have originated in eastern Afghanistan, embroidered by the Hazara people.1 At their open tops, these bags have additional edgings of printed cotton or synthetic material from Russia, China or Pakistan in exactly the same way as the Hazara bags from Afghanistan, so that feature does not help identify this group.

Previously unpublished.

Comparable pieces: Askari and Crill 1997, g.199. 1 See Dupaigne and Cousin 1993, pp.82-5 for Hazara bags of the same type.

Abstract Patterns

Cotton plain-weave ground with embroidery in cotton and wool thread in chain-stitch, raised satin stitch and herringbone stitch, applied cowrie shells

L 36 cm x W 34 cm (14 in x 13 in)

Karun Thakar Collection, London

The dense chain-stitch embroidery on this piece and its geometric design are both typical of Banjara work from South India (see also cat.27-8). It would be worn at the back of the neck by a woman carrying a water-pot on her head (see also cat.15). The Banjara community originally moved around India with the Mughal armies, supplying them with grain and other commodities. Today, many Banjara are still somewhat itinerant but there are also settled groups in several Indian states, especially Goa and Karnataka. Although the Banjaras’ traditional way of life is now disappearing, their embroidery is enjoying a modern revival.

Published: Guy, Crill and Thakar 2014, pl.84.

Comparable pieces: Kwon and McLaughlin 2016, p.72 for a similar pulia from the Shimoga Hills, Karnataka, and pp.133-5 for other pulia

Abstract Patterns

Waziristan, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan, late 19th or 20th century

Cotton plain-weave ground, oss silk embroidered in darning stitch, chainstitch, appliqué, roghan work

L 110 cm x W 197 cm (43 in x 77 in)

Karun Thakar Collection, London

Although there are a number of features common to this Waziri woman’s dress and the outer attire of the women from the Swat Valley, Swat Kohistan, Indus Kohistan and even the nomads just across the border in eastern Afghanistan, there are also enough di erences to identify this garment as Waziri. All of the decoration is geometric, based on vertical columns of triangles, diamonds and long narrow rectangles, lacking oral motifs. The central panel is a single length of embroidered fabric and, although part of the lower section does contain triangular inserts or gores, like the jumlos of Swat Kohistan (cat.43), unlike those garments no cross stitch has been used. The ground cloth is the same darkly saturated hand-spun, hand-woven, indigo-dyed cotton found on so many of the kurtas from the Swat Valley but the dominant pink and red surface darning so characteristic of those textiles is seen only in the earlier densely embroidered panels sewn onto the upper part of the sleeves. Elsewhere, it is replaced here by dark maroon reds with lesser amounts of green, yellow, white and purple. Finally, the sleeves are much narrower and more tapered than the sleeves from any of those other areas. This example is unusual for the use of drawn patterns in roghan work (colored gum made of sa ower-seed paste) separating the vertical rows of geometric motifs in the skirt.

Previously unpublished.

Comparable piece: Askari and Crill 1997, pp.136-137, g.216.

Abstract Patterns

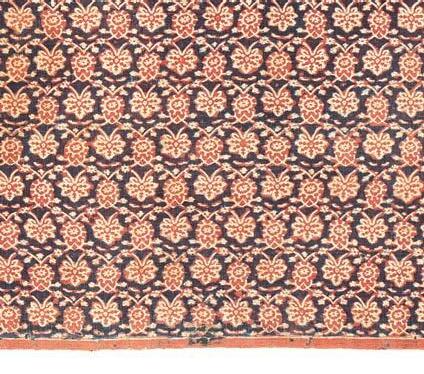

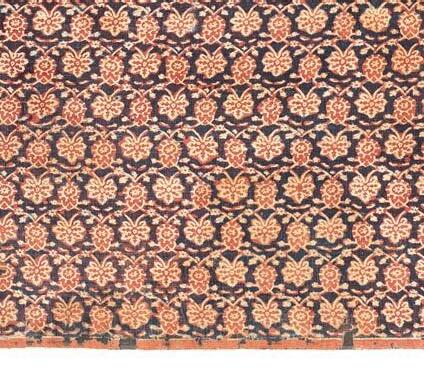

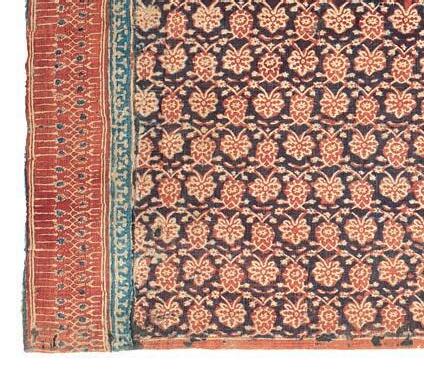

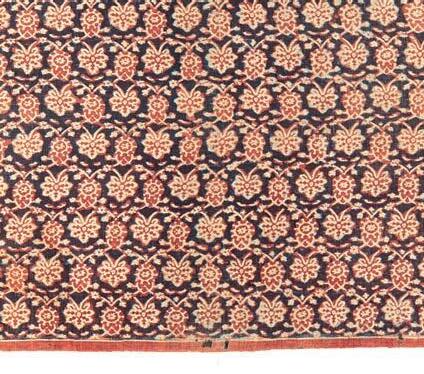

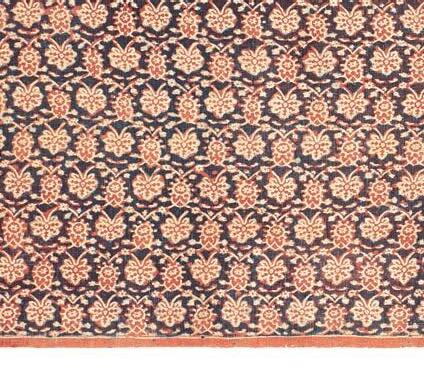

Gujarat, for export to Indonesia, ca. late 16th or early 17th century Cotton, plain-weave ground, block-printed mordants and resists, painted and vat dyes

L 468 cm x W 87 cm (184 in x 34 in)

Karun Thakar Collection, London

Against a dark reddish-blue ground, two types of red and white ower blossoms alternate in horizontal and vertical rows, linked by a continuous thin curved lattice system. Even though these designs have been produced by blockprinting mordants and resists on cotton, the overall e ect recalls much more expensive Ottoman silks and velvets as well as the double-ikat silk patola, also produced in Gujarat and also often made for export to Indonesia (see cat.34). Many such inexpensive block-printed cotton cloths of variable quality re ecting patola in uence have been found in Indonesia (cat.35), but this example with its oral trellis is exceptionally long and its ground color, red overdyed with indigo, is also uncommon. A fragment with this design, found in Egypt, is in the Ashmolean Museum.1

Published:

1

Gujarat, probably Ahmedabad, early 18th century

Silk and metal-wrapped silk thread; draw-loom-woven, with a 1/3 twill double-weave structure in the end, sides and cross borders and a second, di erent woven structure, a 1/3 warp faced and 3/1 weft-face damask, with brocading, in the central eld. Missing one end

L 381 cm x W 50.8 cm (150 in x 20 in)

The Textile Museum 6.29

Acquired by George Hewitt Myers in 1928

The end (pallu) of this waist sash displays four Mughal-style owering plants against a gold ground while the lac-red central eld is lled with o set rows of golden double cloud-band motifs. The narrow side and cross borders all display a "rosette, leaf and stem" meander. Silk and metal-thread patkas woven in Ahmedabad are considered to be among the world’s most beautiful and technically sophisticated examples of draw-loom weaving. In the Mughal period, both fashion and strict protocol demanded that attendance at court required the wearing of one’s nest patka, whether loom-woven or made of block-printed, hand-painted or embroidered cotton, silk or pashmina (cat.71 and 97). But patkas like this one, woven with richly dyed silk and precious metal-wrapped thread, were the most costly and conferred the highest status.

Published: Jain 1994, p.63, g.8; Mackie 2015, p.437, cat.no.10.26.

Comparable pieces: Goswamy 2002, nos.1,9, 20; Jain 2016, cat.nos.46-53; Crill ed. 2015, pls.121-122.

First published on the occasion of the exhibition Indian Textiles: 1,000 Years of Art and Design at the George Washington University Museum and The Textile Museum, Washington, D.C.

Copyright © 2021 The George Washington University Museum and The Textile Museum. All rights reserved under international and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. Except for legitimate excerpts customary in review or scholarly publications, no part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or information storage or retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher

Karun Thakar Collection photographs © 2021 Karun Thakar Collection. Photography by Desmond Brambley

The Textile Museum collection photographs © 2021 The George Washington University Museum and The Textile Museum, Washington, D.C.

The George Washington University Museum and The Textile Museum 701 21st Street, NW, Washington, D.C. 20052 202-994-5200 | museum.gwu.edu

Produced for the George Washington University Museum and The Textile Museum by Hali Publications Limited, 7 Ability Plaza, Arbutus Street, London E8 4dt, UK | www.hali.com

Designed by Struktur Design Limited, London Printed and bound by EBS, Verona, Italy

Library of Congress Control Number: 2021909329

ISBN 9781898113966

Cover: Detail of cat.105 Back cover: Detail of cat.130