11 minute read

Coastguard Buildings

from Joan Eardley

73 · Eardley’s watercolour paints (with ear of corn)

Private collection

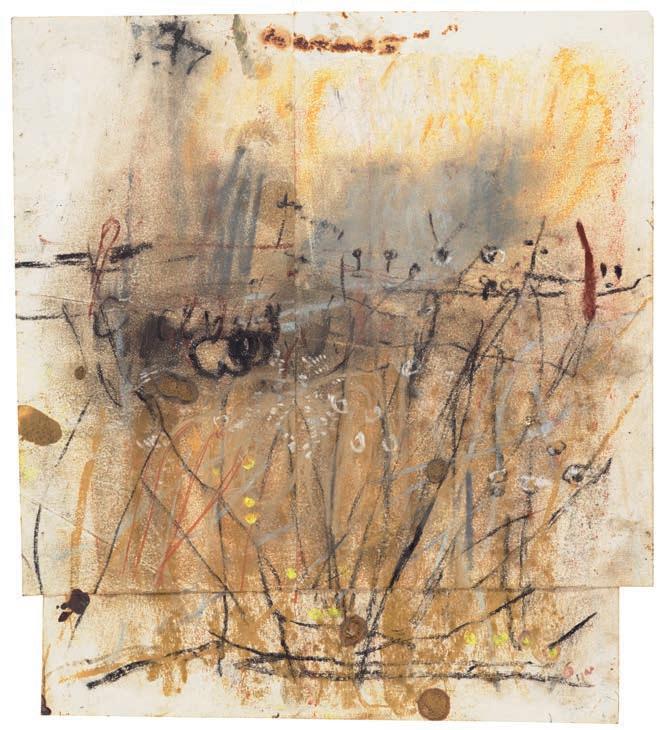

74 · Autumn Flowers and Seed-heads, c.1960

Pastel and oil on three sheets of paper, 25 x 22.6 cm (irregular) National Galleries of Scotland: presented by the artist’s sister, Pat Black, 1987

but most had a more experimental, preparatory role. She often started on a single sheet and then attached additional sheets in a piecemeal fashion with paperclips. Over 1,300 drawings were found in her studios after her death. They were integral to her working practice – partly as studies to be translated into larger paintings, partly as stages in a thinking process. William Macaulay, who ran The Scottish Gallery in Edinburgh, wanted more of her drawings to sell, but Eardley had reservations, having let some go and later regretted it. She explained that ‘previously I have set little value on my drawings, except for my own personal use – and they have often become destroyed during the working of a picture’.24 But having recently been kept indoors through illness, she had sorely missed them: ‘I found myself so much in need of drawings, to let me feel some contact with my subjects and my work when I was unable to get around last winter – that I swore I would not sell any for a long time, once I had managed to do some more’.25

In 1960 she began to stick real grasses, stalks and seed-heads into her landscape paintings, embedding them in her home-made, claggy oil paint. There are not many works of this type: the most substantially collaged paintings are the richly matted Seeded Grasses and Daisies, September, 1960 [75] and Summer Fields, 1961 [76]. Ever the realist, instead of painting grasses, she simply picked up real ones and pressed them into the congealed paint. This collage approach seems to slightly pre-date her use of collage in her Glasgow paintings, when she stuck newspaper and sweet wrappers onto her portraits of children. Some of the seascapes have newspaper embedded in the foaming waves to give them three-dimensional substance, such as January Flow Tide [99], which also includes a piece of silver foil. She stuck a newspaper crossword into the clotted paint in one seascape, allowing the squares of the puzzle to read as a fishing net.26

Eardley included Seeded Grasses and Daisies, September in her show at The Scottish Gallery in Edinburgh in May 1961. The critic Sydney Goodsir Smith saw Eardley hanging it and cautioned her that it would be ‘bits of dust’ within a year.27 Eardley was furious and argued back: she knew her craft and was confident it would last. (It has.) The artist Anne Redpath (1895–1965) also saw and admired this painting in the exhibition, but she too wondered about its longevity.28 Eardley does seem to have had second thoughts about the process, and never used it again to the same degree. It was

11 · Self-portrait, 1943

Oil on plywood, 53.4 x 45.7 cm National Galleries of Scotland: purchased 2001

2 JOAN EARDLEY

DISCOVERS CATTERLINE

Joan Eardley’s parents, Irene Morrison (1891–1981) and William Eardley (1888–1929), married in 1917 in Glasgow, where he was stationed during the First World War.1 After the war, William ran Bailing Hill dairy farm at Warnham, near Horsham in West Sussex. Joan was born there on 18 May 1921. William had been gassed in France and left traumatised, and had severe depression. In 1925 the family moved to Lincoln, where he worked for the Ministry of Agriculture, but by the end of 1926 he was in financial difficulty. William and Irene separated. Irene, Joan (then aged five), her younger sister Pat (1922–2013) and their aunt Sybil (1893–1984) moved into Irene’s mother’s house in Westcombe Park Road, between Blackheath and Greenwich in south-east London. Joan’s father moved to Penrith in Cumbria (then Cumberland), where he worked as an Inspector of Livestock. Burdened by financial problems and depression, he took his own life in December 1929, aged 41.2 With war looming, in 1939 the family moved to Auchterarder, near Perth in Scotland, where they had relatives. In January 1940 they settled in a house at 170 Drymen Road, Bearsden, an affluent, almost rural suburb on the north-west side of Glasgow. Eardley enrolled at the Glasgow School of Art soon after.

One of the first people she met at the School of Art was fellow student Margot Sandeman (1922–2009), who would remain a lifelong friend. They spent several holidays together in a little bothy at Corrie on the Isle of Arran, on one occasion going on a trip in a horse-drawn cart [12]. Basic rural life held a strong appeal for Eardley from the outset of her career as an artist.

Eardley emerged as a leading student at the School of Art. Cordelia Oliver (1923–2009), who became her close friend (and stalwart champion in later years, through her work as an art critic), was a year behind her, but they shared some classes. She recalled:

I retain a vivid memory of Joan Eardley at work in the life-class … the way she would stand for long minutes at a time, assimilating the model on the throne, not in detail so much as in the thrusts of the pose and the relationships of form with form, volume with space.

Only then would she make her chalk marks on the paper, swiftly and with meaning.3

This approach involving intense looking and concentrated recording would be the foundation stone upon which Eardley’s art was based. She graduated with her diploma in 1943, her self-portrait [11] winning the Guthrie Prize. Reluctant to go into teaching or be conscripted, for nearly two years she worked as a joiner’s labourer at a small boat-building firm belonging to friends of the family, John A. Russell, in Bearsden.4

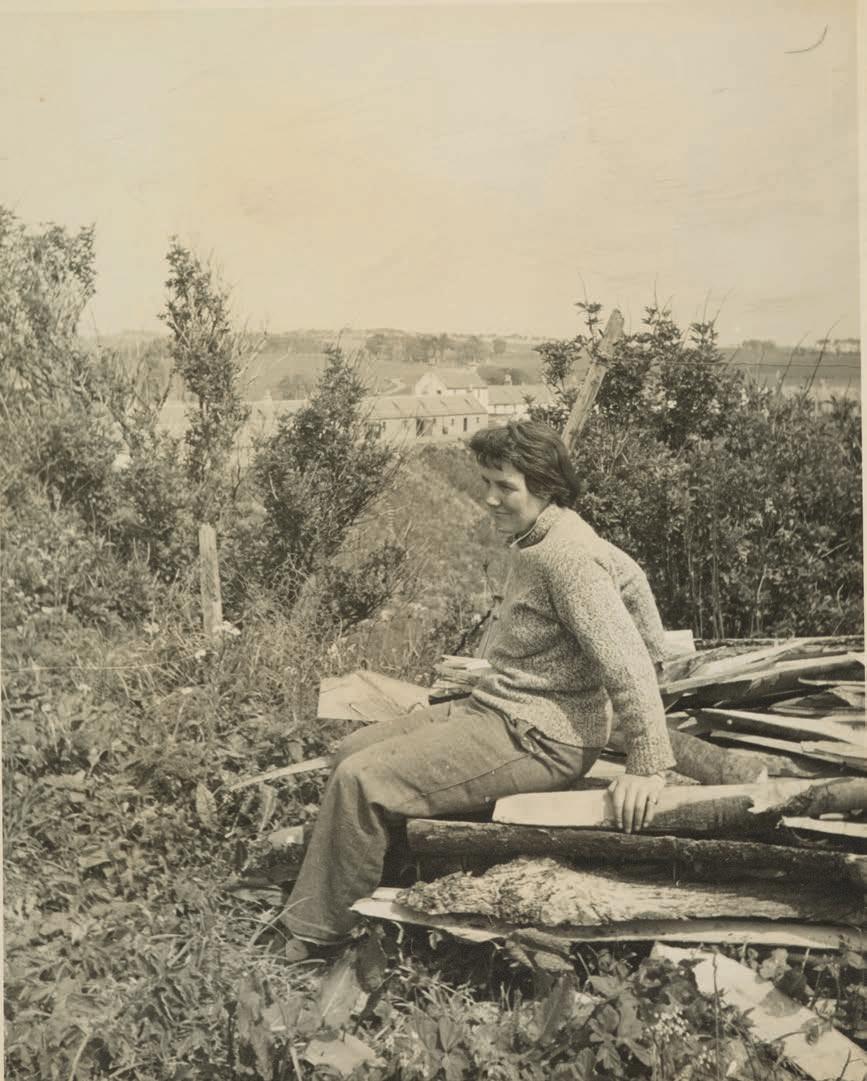

31 · Joan Eardley seated on a pile of wooden boards, c.1955

Photograph by Audrey Walker Joan Eardley Archive, National Galleries of Scotland Archive: presented by the artist’s sister, Pat Black, 1987

32 · The toilet behind No.1 South Row, c.1957

Photograph by Joan Eardley Joan Eardley Archive, National Galleries of Scotland Archive: presented by the artist’s sister, Pat Black, 1987

bedwarmer, filling it up from the water she boiled over her fire. Margot Sandeman later recalled: ‘She had mice in the cottage. At dusk they would come out and run about, jumping in and out of the coal bucket. She didn’t mind it at all!’12

Eardley’s cottage was fully exposed to the raging easterly gales which came in from the North Sea. It was also the nearest cottage to the foghorn beyond the lighthouse at Kinneff, which would sometimes sound for days on end. None of the cottages on the South Row had letterbox slots in their doors, for the simple reason that they would have blown open and let in the wind and rain. On one stormy winter night, Eardley wrote to Audrey Walker: poor little No 1 is getting rocketed about. Every now and then by an extra hard blast of wind the door is blown open and what amounts to about a bucket full of rain is sloshed in through the open door … Nothing we can do to assure the chimney staying in place – or the roof for that matter … The rain has poured into the studio so that the floor is one enormous lake.13 She added, typically, that she would like to go out and paint, ‘though I don’t know if I’ll be able to keep my easel standing’.

The South Row cottages all had chemical toilets housed in little wooden sheds at the front, except Eardley’s, which had a toilet at the back. Late in 1957 she had her toilet shed remodelled, adding a new door [32]. A cause for mock celebration, she mentioned it in a letter to Audrey Walker: ‘It’s got a wINDow and it’s going to have a curtain, so as those folks what is shy can pull that wee lace curtain – and feel right soft and cosy.’14 Walker recorded that the door was made from a rejected painting on its stretcher, which could presumably be enjoyed from a seated position.15

Eardley was helped in a lot of her labouring work by Angus Neil (1924–1992). Born in Kilbarchan in Renfrewshire, he had a troubled upbringing and had

81 · Boats on the Shore, c.1963

Oil on board, 101.6 x 115.6 cm National Galleries of Scotland: Scott Hay Collection, presented 1967

make something that can hang between reality and abstraction with this sort of subject. I can’t achieve it anyway.’9 The sea offered more scope as her more energetic style evolved.

Previously, the sea had been an obstacle for her when she approached it as a realist artist; now it was the ideal subject as she embraced the painterly values of abstraction. She admired the paintings of her contemporary Alan Davie (1920–2014), the Scottish Abstract Expressionist who won international acclaim in the late 1950s. She had a reproduction of one of his paintings on the wall in her cottage: ‘I’ve pinned that Alan Davie on the wall next to [the] map. It’s really a very fine painting, I wish I could see it. They are tremendous shapes these vicious straight lines and the 3 triangles.’10 The Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art opened in Edinburgh in 1960 in the Royal Botanic Garden in Edinburgh, providing, for the first time in Scotland, a permanent display of contemporary international art. Eardley mentions visiting the Gallery in one of her letters, and picked out two works she particularly liked, by Jean Dubuffet and Antoni Tàpies.11

Eardley’s late sea paintings feature certain recurring motifs associated with fishing, such as boats, tall poles, nets and creels. Before thinking about these works as paintings, it may be helpful to examine all this fishing paraphernalia and say something of the people who used it. Although she did not paint the people of Catterline, their working materials and their cottages and crops act as analogues for their lives. Eardley was instinctively drawn to poor communities who lived on the margins, to people whose way of life was under threat. Even though they are largely devoid of figurative references, her Catterline paintings are as much about people and community as are her paintings of Glasgow children. Old nets can serve pictorial ends, but they can also speak of human endurance and resilience in the face of change.

By the late 1950s there were just four fishing boats left in Catterline: the Hopefull, the Linfall, the Mascot and the Fear Not. 12 They were shallow-draught boats with inboard engines. They can be seen in many of Eardley’s paintings and drawings and can be identified by their numbers and their colour: the blue Linfall and the green Mascot are the boats most often seen, featuring, for example in Green and Blue Boats [80] and Boats on the Shore [81]. Designed and built in the early years of the twentieth century, these two boats were 21 feet long and were old ship’s lifeboats. They had two main catches: lobster and crab caught in creels, and haddock and cod caught on a long line or a short line (known as a ‘smaline’). The Hopefull (a267) belonged to ‘Big’ Jim Stephen (who lived at No.21), the Mascot (a440) to the Watt family, the Linfall (a471) to Harry Wylie and the Fear Not (a627) to Alec Criggie.13 The Hopefull and the Meanwell were identical, purpose-built fishing boats made in Cowie, Stonehaven, in 1907.

These fishermen and their families lived in cottages overlooking the bay. Eardley knew them all and exchanged words with them about the weather on a daily basis. Most of the villagers were connected in some way, and many had been born in Catterline, as had their parents and grandparents. For example, Jim Stephen who owned the Hopefull married Annette Soper, the schoolteacher who had first

104 · Seascape (Foam and Blue Sky), 1962

Oil on board, 94 x 167 cm National Galleries of Scotland: the Henry and Sula Walton collection, bequeathed 2012

feelings and experience went into these pictures? Big, semi-abstract paintings with loose, gestural brushwork are often called ‘Expressionist’. If she was an Expressionist, what exactly was she expressing? Autobiographical readings of pictures often get short shrift, but it is hard to avoid them in Eardley’s case. When we know of her introversion and awkwardness, coupled with her burning, passionate nature, and the frustrations that chance had thrown at her, the paintings look like declarations of an emotional condition. Writing on the train to London, she described herself as being ‘Like a bottle with the bung stuck in’ when she was unable to paint.56 She was drawn towards raging seas for a reason. The lack of a central focus, the avoidance of descriptive detail, the need to paint things in constant movement, things which never rested, all look like metaphors for her own state of mind. Angus Neil viewed Eardley’s predicament, loving two women – Margot Sandeman and Audrey Walker – both of whom were married and had families, as being one of constant torment. He knew Eardley as well as anyone; he believed that her emotional frustrations were channelled into an ‘utter dedication to her muse’: her art.57 Cordelia Oliver, a friend from the Glasgow School of Art, had a similar view, although in her monograph published in 1988 she was not explicit. She noted that ‘the black dog of melancholia hounded Joan Eardley intermittently throughout her life’ and believed that it was because she yearned for stable and constant companionship which she could never achieve.58 Oliver seems to have been unaware of the love which bound Eardley and Lil Neilson in the last year of her life, when she produced some of her greatest works.