Published on the occasion of the exhibition “The Art of Impermanence: Japanese Works from the John C. Weber Collection and Mr. and Mrs. John D. Rockefeller 3rd Collection,” organized by Asia Society Museum.

Asia Society Museum, New York

February 11–April 26, 2020

© Asia Society, New York, NY, 2020

All rights reserved. This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publishers.

Published by Asia Society 725 Park Avenue New York, NY 10021

www.AsiaSociety.org

Officina Libraria via Carlo Romussi, 4 20125 Milano – Italy www.officinalibraria.net

Project Manager: Ken Tan

Curator: Adriana Proser

Production Coordinator: Maia Murphy

Editorial Consultant: Jane Oliver

Copy Editor: Catherine Benson

Indexer: Valerie Zinner

Designer: Rita Jules, Miko McGinty Inc.

Typefaces: Metric, Noe, and St Croce

Printing: Intergrafica, Verona, Italy

Library of Congress Control Number: 2019952765

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN: 978-88-3367-083-6

The paper in this book meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

Cover illustrations: (front): Detail of cat. no. 68; (back): detail of cat. no. 65

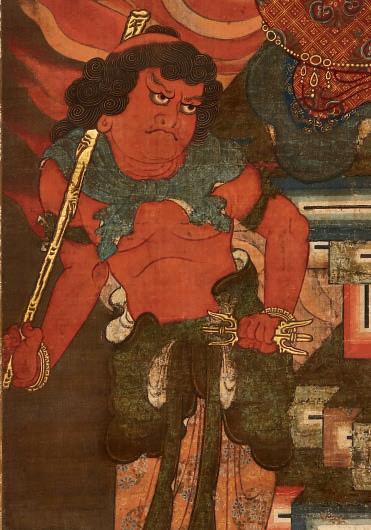

Frontispiece: detail of cat. no. 40

Page 6: detail of cat. no. 29

Page 10: detail of cat. no. 13

Page 12: detail of cat. no. 66

Page 14: detail of cat. no. 43

Pages 44–45: detail of cat. no. 63

Pages 46–47: cat. no. 7

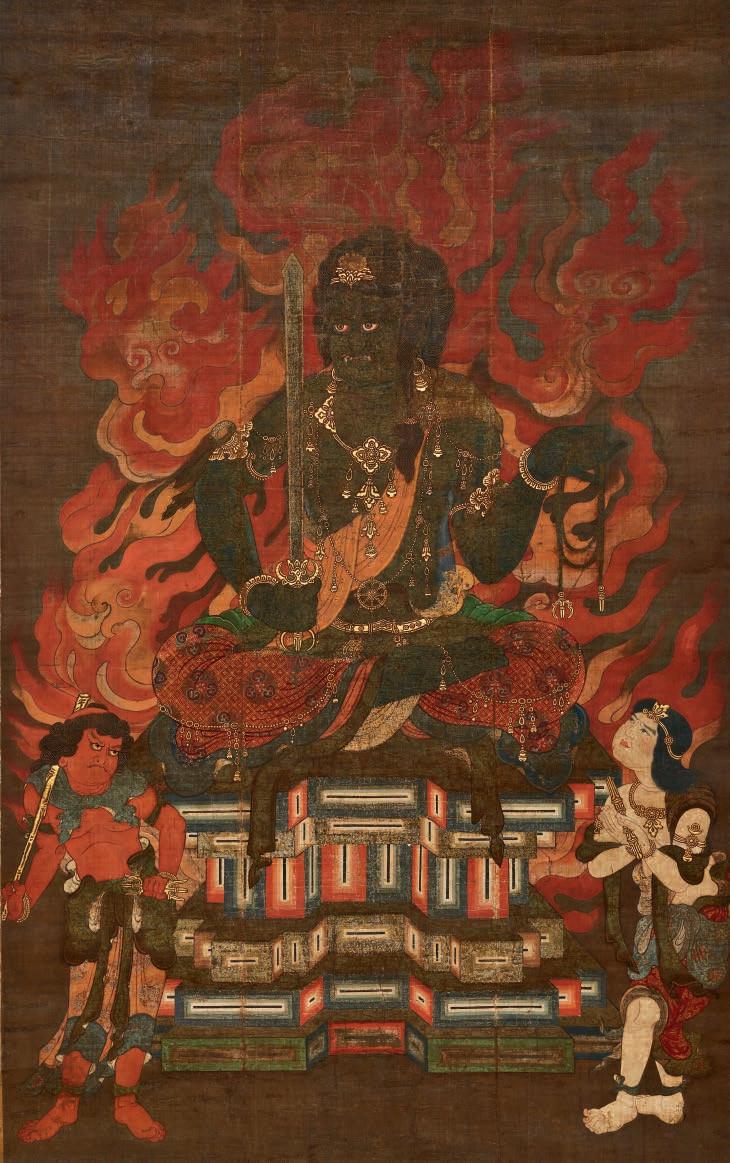

Pages 70–71: detail of cat. no. 41

Pages 129–130: cat. no. 49

Pages 155–156: detail of cat. no. 65

Pages 190–191: Map designed by Anandaroop Roy

President’s Foreword Josette Sheeran 7 Director’s Preface Boon Hui Tan 8 Curator’s Acknowledgments Adriana Proser 11 Exhibition Funders and Note to the Reader 13

Ephemeral 14 Melinda Takeuchi Works in the Exhibition 45 Adriana Proser with contributions from Maria Slautina I Retrieving Lost Worlds 47 II Buddhism: Perpetual Impermanence 71 III Tea: Choreographed Ephemerality 131 IV Transforming Impermanence into Art 157 Map 190 Timeline 193 Glossary 194 Selected Readings 197 Contributors’ Biographies 202 Index 203 Photography Credits 208 CONTENTS

The Art of the

THE ART OE THE EPHEMERAL

Melinda Takeuchi

Melinda Takeuchi

Heartfelt thanks to Gina Barnes, Thomas Hare, Gregory Levine, Susan Matisoff, Julia Meech, Jane Oliver, Andrew Pekarik, Jonathan Reynolds, Joseph Seubert, Lori Van Houten, and John Weber. You are generous friends and colleagues.

1 See Gina L. Barnes, “A Hypothesis for Early Kofun Rulership,” Japan Review, no. 27 (2014): 3. The earliest surviving keyhole-shaped tomb, located in the Makimuku complex in Nara Prefecture, dates from the early third century. See p. 14.

2 Simon Kaner, “Archaeology: A Potted History of Japan,” Nature 496 (April 18, 2013): 302.

3 Victor Shnirel’man, “Nationalism and Archaeology,” Anthropology and Archaeology of Eurasia 52, no. 2 (Fall 2013): 13. Notions of a Golden Age or idealized vanished civilizations include the Chinese Era of the Sage Kings Yao and Shun, the Garden of Eden, the Age of Pericles, Shangri-La, and Atlantis.

Retrieving Lost Worlds

From the perspective of the present, all prehistoric societies are by definition ephemeral. No matter how long they endured (the civilization that produced the oldest objects in this exhibition lasted some 10,000 years), the cultures that created them have vanished. In the twinkling of an eye, tomorrow becomes yesterday. In the absence of concrete knowledge of these preliterate epochs— we do not even know what language the earliest people spoke—our names for Japan’s three ancient civilizations seem oddly off base. Jōmon (ca. 15,000–300 BCE) means “cord marking,” a term inspired by patterns created by impressing twine-wrapped sticks on some (but in actuality a minority) of the ceramics. The subsequent Yayoi civilization (ca. 300 BCE–300 CE) got its designation from Yayoi-chō, a district in Tokyo’s Hongō Ward, where construction in 1884 unearthed an unrecorded style of pottery. (A more accurate name would reflect the era’s adoption of agriculture and metallurgy from the Asian continent.) The Tumulus (in Japanese, Kofun, meaning “old tomb”) period (300–710) refers to the distinctive grave mounds that characterize its culture, though such keyhole-shaped tombs had existed earlier.1

We are fortunate, however, to find traces of civilizations preserved in the earth. The impermanence of past epochs is mitigated by the serendipitous yielding up of clues. Some objects, like the Flask in the Shape of a Leather Bag (cat. no. 9), reproduce in durable form things that were originally created from perishable material. Every object we dig from the ground has some story to tell to compensate for the fact that, like so many human endeavors, the society that produced it has passed from the scene.

Interpreting these stories entails both science and art. We must recognize also that archaeological findings are inflected by contemporary ideological perspectives. Different narratives around the same material served varied purposes throughout history. To give but one example: in the first half of the twentieth century, a period of intense Japanese militarism, archaeologists balked at accepting dates that placed early artifacts anterior to the span of time presented in the official chronologies discussed below. These “histories” bolstered the chauvinistic claim that the imperial house sprang from divine origins.2 Today, emperor centrism in Japan has yielded to the pride of being able to boast one of the world’s oldest ceramic traditions. In the words of Victor Shnirel’man: “A huge role is played by imagination and emotions turned toward a ‘golden age.’” 3

Archaeology and Notions of Time in Japan

How did Japanese perceive time before adopting the western calendar in the late nineteenth century? The dominant paradigm emerged from two ancient “histories” compiled retrospectively in the early eighth century, when the Yamato clan was seeking to solidify its power. Chinese emperors had long sponsored official histories to make sure their versions were the ones told. Following suit, the Yamato house commissioned the Kojiki (Chronicle of Ancient Matters, 712) and the Nihon shoki (Chronicles of Japan, 720). Assembled from oral traditions, myth, folklore, ancient songs, clan genealogies, professional reciters, and probably the compilers’ imaginations, these documents divided the past into two segments. The “Age of the Gods” detailed the creation of the Japanese

15

1 Flame-style Vessel Japan

Middle Jōmon period, 3500–2500 BCE

Earthenware

H. 11⅝ x Diam. 11⅝ in. (29.5 x 29.5 cm)

John C. Weber Collection

In the 1930s, when Japanese archaeologists unearthed a deep pot with dramatic, twisting extrusions like this one, they knew they had come upon one of the world’s most dynamic pottery forms. They described it as “flame- decorated” (kaen- shiki ) because the sculpted extrusions reminded them of flickering fire. Why these vessels were made remains a mystery. No records exist of the ancient Jōmon people who made them.

From the burn marks on the bases of such pots we might discern that they were used for cooking. However, it is likely the marks are simply the result of the firing process. Given the impracticality of their elaborate designs, scholars traditionally have assumed that the semi-sedentary Jōmon people made them for the preparation of food or drink for consumption during rituals.

Like all Jōmon vessels, this one is coil-built by hand out of moist, soft clay. The potter added a saw-toothed mouth rim that is further embellished with eight cockscomb-shaped “handles” above the main cylinder. Vertical and swirling ridges ornament the exterior sides, and the imprint of ridges showing veins of a leaf appear on the flat foot of the pot. Once the clay had dried, the vessel was fired in a bonfire as hot as 900°C. AP

References

“Jōmon Culture (ca. 10,500–ca. 300 B.C.),” Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, accessed August 7, 2019, https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/jomo/hd_jomo.htm.

Miho Museum, A New Yorker’s View of the World: The John C. Weber Collection (Shigaraki: Miho Museum, 2015), 230.

48

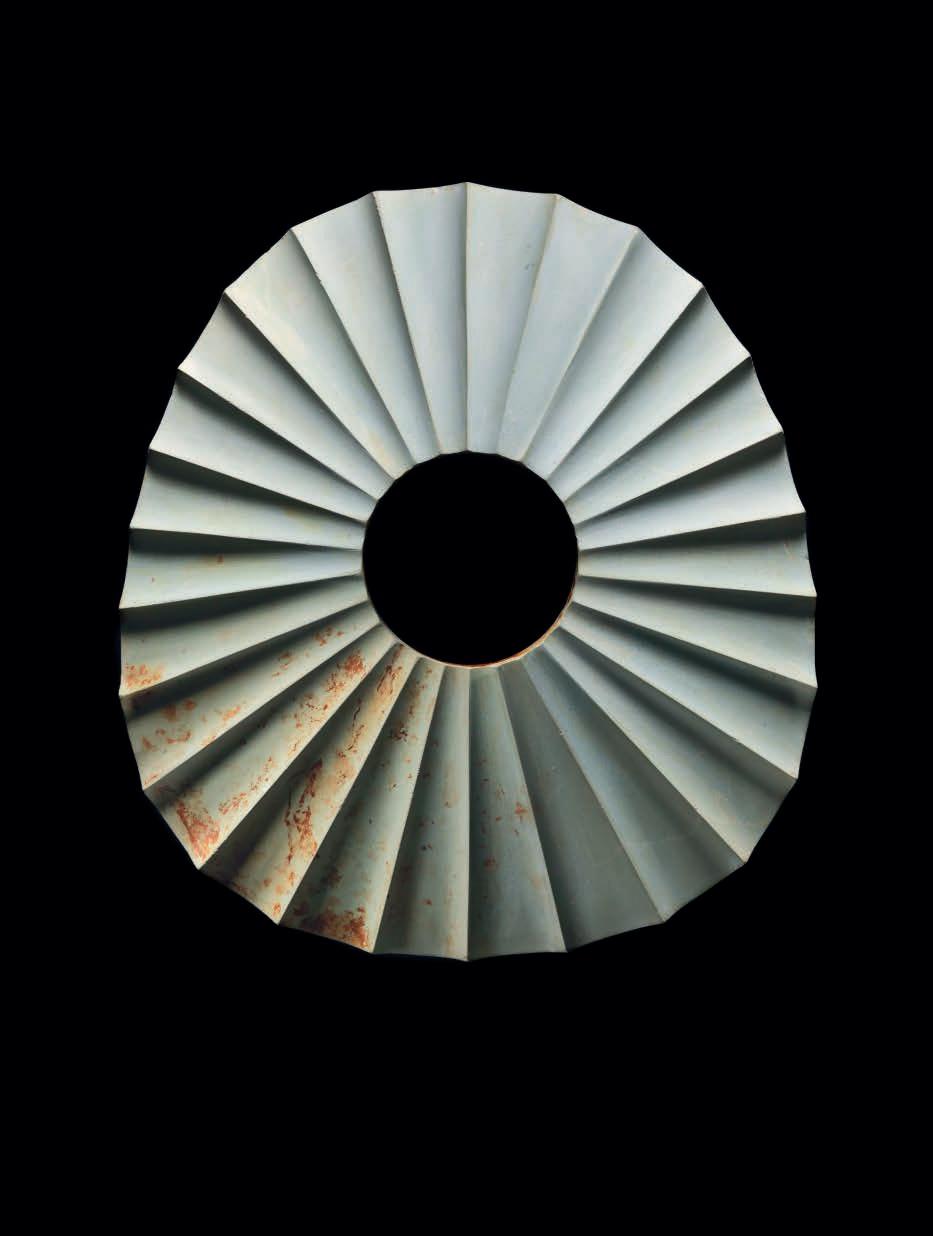

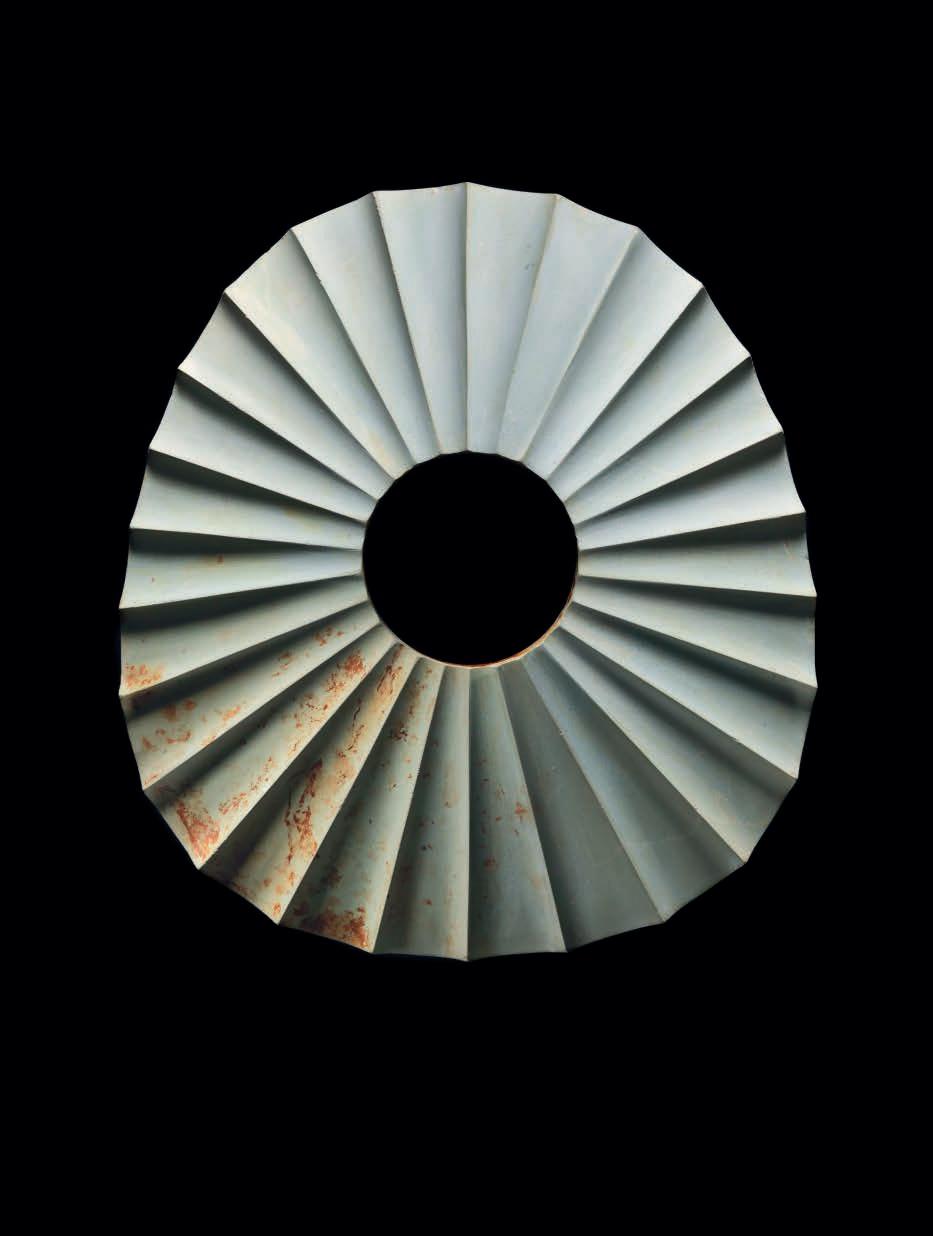

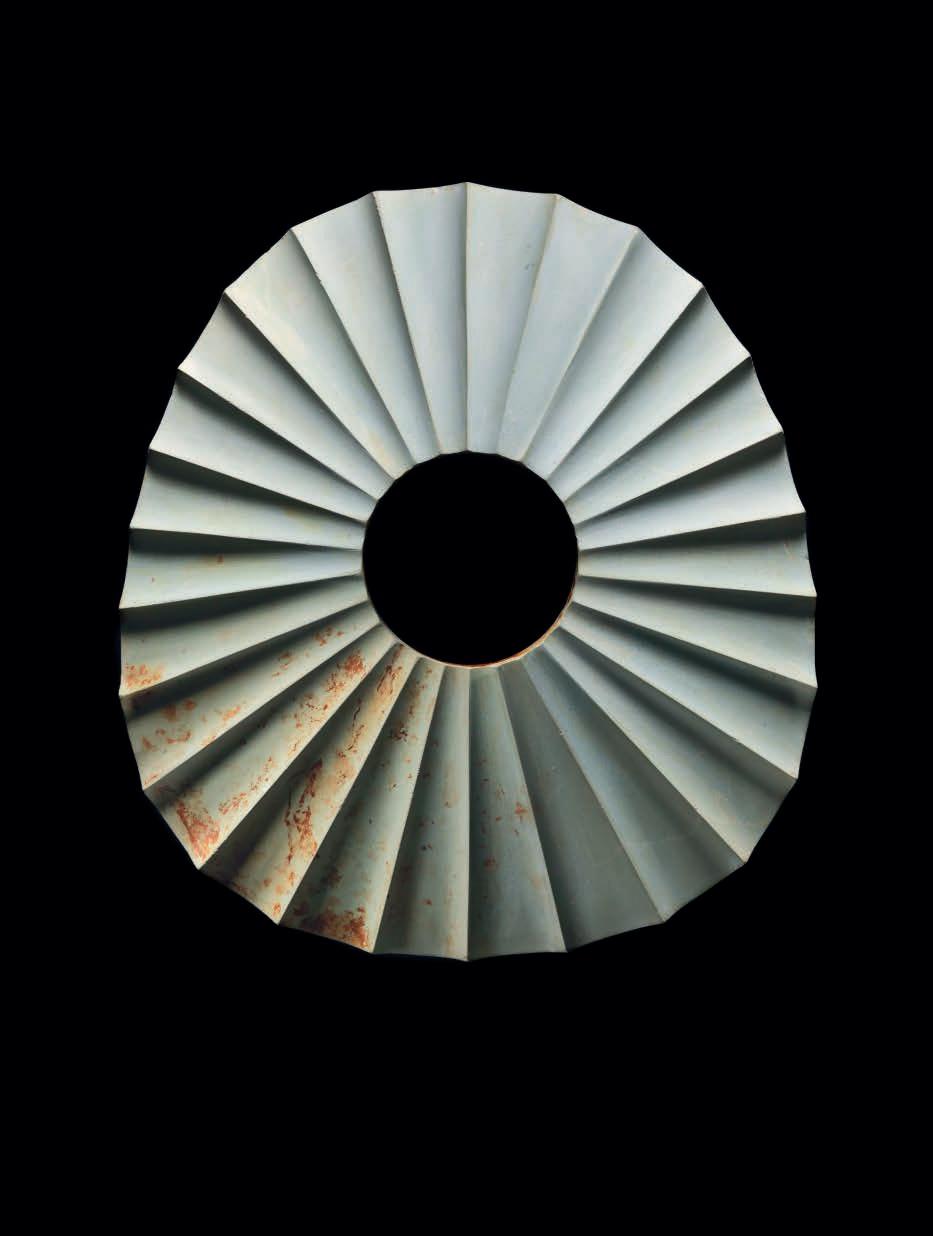

7 Wheel-shaped Ring (sharinseki) Japan, Nara Prefecture, Shimanoyama Tomb

Tumulus period, 4th century Green tuff with red pigment

H. 8½ x W. 7¾ x D. ⁹⁄₁₆ in. (21.5 x 19 x 1.5 cm)

John C. Weber Collection

This shell-patterned, wheel-shaped stone ring (sharinseki) is one of 132 stone discs discovered in the main chamber of the fourth- century Shimanoyama tumulus in present- day Nara Prefecture. Modeled from green tuff with traces of red pigment, it imitates talismanic ornaments from the earlier Yayoi period made of shells from the seas around the islands of Okinawa. At the end of the Yayoi period, craftspeople used bronze, another exotic material, to replicate these amulets. Bronze bracelets have not been excavated from burial mounds of the Tumulus period, but stone and shell ones have been found side by side. In the Shimanoyama tumulus only stone sharinseki were discovered, suggesting that earlier Yayoi magical rituals might have waned or acquired a new meaning.

Like bronze mirrors also found in burial settings, discs of unusual shapes and materials likely had a spiritual significance, especially given that no ancient anthropomorphic representations of gods have been unearthed in Japan. Scholars have proposed that the person buried in the Shimanoyama tomb, whose clay-packed dugout log coffin was covered with stone rings like this one, was a shamaness.

The Department of Scientific Research at The Metropolitan Museum of Art recently tested this object with X-ray fluorescence spectrometry and Scanning Electron Microscopy. The team found the composition to be very similar to three smaller green stone pieces in the museum’s collection that they were able to test by X-ray fluorescence spectroscopy, including the same trace elements signatures (Rb, Sr, Y, Zr and Ba). Testing of one of the Metropolitan objects (1975.268.387) by X-ray Diffractometry confirmed that the rock is not steatite, nor chlorite schist, nor jasper. It is green zeolitic tuff, or, simply, green tuff, based on the presence of quartz, clinoptilolite (a zeolite mineral), muscovite (a mica) and albite (a feldspar), as well as the general chemical composition. Because of the notable similarities in chemical composition, the green tuff of the Weber stone and that of the Metropolitan pieces (1975.268. 386, 387, and 389) likely came from the same rock formation. MS

References

Department of Scientific Research, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, 2019. Mizoguchi, The Archaeology of Japan, 250–53, 260–61.

Richard J. Pearson and Takashi Doi, Ancient Japan (Washington, DC: Arthur M. Sackler Gallery; New York: G. Braziller, 1992), 251. Shiraishi Taichirō, “An Archaeological View of the Dual System of Religious and Secular Chieftainship,” Bulletin of the National Museum of Japanese History 108 (October 2003): 117.

60

15 Reliquary Shrine (zushi) with Sixteen Rakan Japan

Kamakura period, 13th–14th century

Wood, rock crystal, pigment, and gilt bronze

H. 7 x W. 6 in. (17.8 x 15.2 cm) (closed)

John C. Weber Collection

This elaborately painted portable reliquary shrine, known as a zushi in Japanese, houses five relics (round beads of different materials) behind rock crystal in a circular concave recess at the center of the shrine. The relics are on a gilt-wood platform in the form of a lotus flower. Around the recess, the craftsman painted flames in gold (much of the gold has been lost), so that the relics appear as part of a flaming jewel set upon a larger lotus pedestal with an elegant canopy. The relics symbolically represent the Historical Buddha, Shaka, which accounts for the inclusion of the Sixteen Rakan (Sanskrit: arhat), the ascetic followers of Shaka who were present at his death and nirvana and who venerate his relics, and the flanking bodhisattvas Monju and Fugen. These, as well as guardian figures on the interior of the shrine doors, have been painted in colorful hues and with gold details on their garments. Twin dragons, one red and one golden yellow, their claws outstretched toward a wish-fulfilling jewel, appear as additional guardian figures on the inner surface of the recessed central panel.

There are four Directional Devas on the interior side of both doors, making a total of eight Directional Devas. These protectors of Buddhism are also considered harbingers of peace and prosperity. On the proper right are Bishamonten (North) holding a stupa, Rasetsuten (Southwest) grasping a sword, Taishakuten (East) holding a vajra, and Enmaten (South), who holds his hand with his palm facing forward. On the proper left are Futen (Northwest), holding a staff with a finial of the crescent moon and sun, Suiten (West), Ishanaten (Northeast) with a three-pronged spear, and Katen (Southeast). AP

76

20 Heart Sutra (Hannya Shingyō) Japan

Late Heian or Kamakura period, 12th–13th century Handscroll; gold and silver pigment on paper with reddish purple dye

H. 1⅞ x W. 19 in. (4.6 x 48.4 cm)

John C. Weber Collection

This diminutive sutra scroll likely functioned as a personal amulet that was kept in a bag and hung around the neck of an aristocratic woman. Commissioning a sutra was considered to be a means of gaining merit, and the faithful believed the text on this scroll, the Heart Sutra, could have protective and healing power. The full and original Sanskrit name of the sutra is Prajnaparamita-hrdayam Sutra (Japanese: Hannya Shingyō), which translates from Sanskrit as “The Heart of the Perfection of Wisdom,” abbreviated as the Heart Sutra. This brief and easily memorized scripture, which concerns emptiness of self and all phenomena, is one of the most popular sutras in the Buddhist world.

This sutra begins with a long frontispiece of grasses and plants delineated in gold and silver pigments. The text follows in tiny, spindly but elegant characters in block script (kaisho) written in gold on paper dyed with a reddish purple colorant, brazilwood, a dye extracted from the wood of a variety of leguminosae plants found in Asia, such as Caesalpinia sappan or Caesalpinia echinata. This conclusion is based on the identification of the dye molecule brazilin following analysis of a microscopic sample by surface- enhanced Raman spectroscopy in the Department of Scientific Research at The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

The back of the scroll is also painted in gold and silver with grasses, a willow tree, a stream, and insects. There is a preliminary, short sheet of indigodyed paper that serves as a protective cover. AP

References

Department of Scientific Research, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, 2019.

Fabio Rambelli, Buddhist Materiality: A Cultural History of Objects in Japanese Buddhism (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2007), 89ff.

84

21 Shaka Buddha Japan

21 Shaka Buddha Japan

Early Nara period, ca. 700

Bronze

H. 11¾ x W. 7⅝ x D. 6⅜ in. (29.7 x 19.2 x 15.2 cm)

John C. Weber Collection

This serene seated bronze buddha is a representation of the Historical Buddha, Shakyamuni (Sage of the Shakyas), or Shaka in Japanese. According to tradition, after many previous rebirths he was born into an elite family of the Shakya clan, whose territory lay on what is now the border between northeastern India and Nepal. The date of his birth is believed to be 563 BCE, but some sources suggest that he was born as much as a century later. After leaving his princely life to pursue what became a long search for enlightenment, he is said to have sat under a tree to meditate and in the course of one night reached nirvana, becoming a buddha. The Buddha’s reincarnations and ultimate enlightenment exemplify the transient nature of life espoused by Buddhists. In this image, Shaka appears with his hands in the gesture of reassurance (abhaya mudra). Buddhism spread to Japan through close cultural ties that linked it in the sixth century to China and Korea. Like other seventh- century Japanese seated buddha images, the robe ripples over a rectangular platform, harkening back to a style of sculpture that was popular in China in the first quarter of the sixth century. Small, bead-like protrusions meant to represent curls of hair cover his cranial bump (ushnisha), which symbolizes wisdom, and the rest of his head. His elongated earlobes and the folds in his neck are other features that mark him as a buddha. AP

86

98 Details of cat. no. 27 Details of cat. no. 26

Cat. no. 27

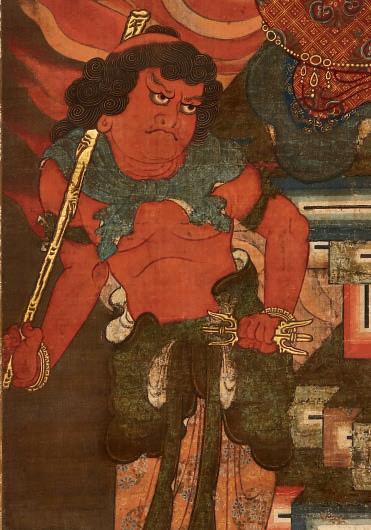

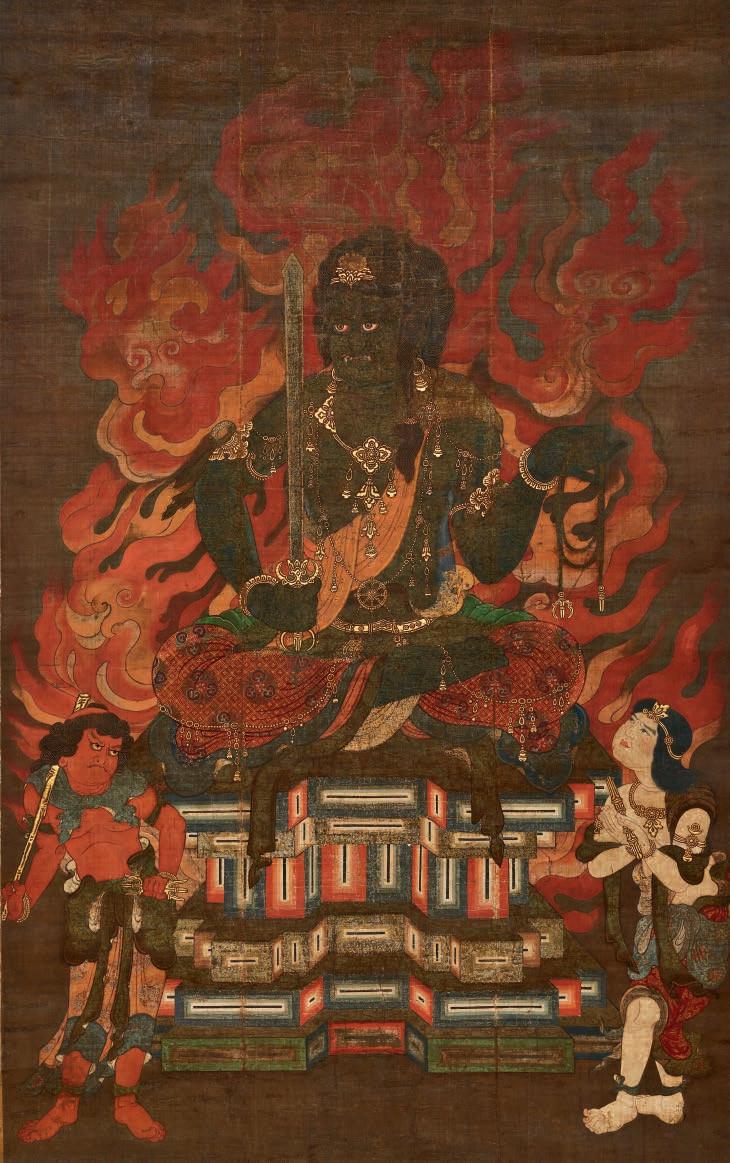

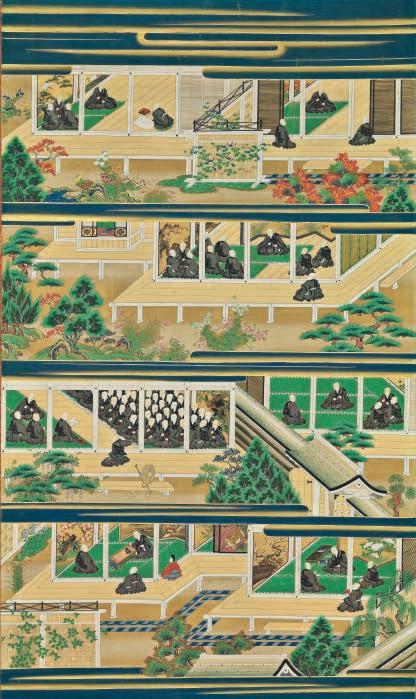

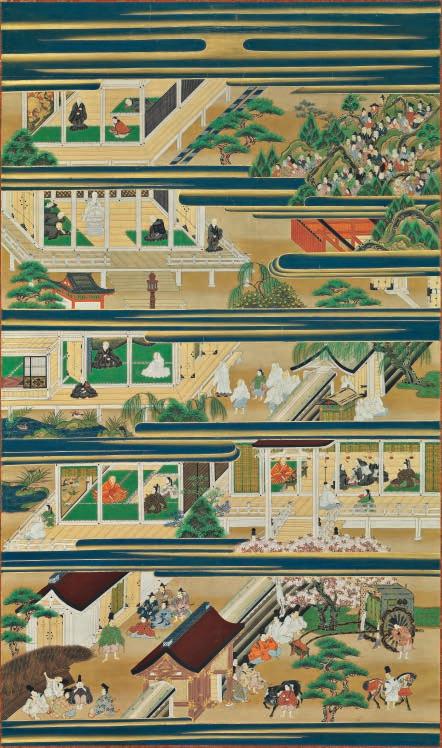

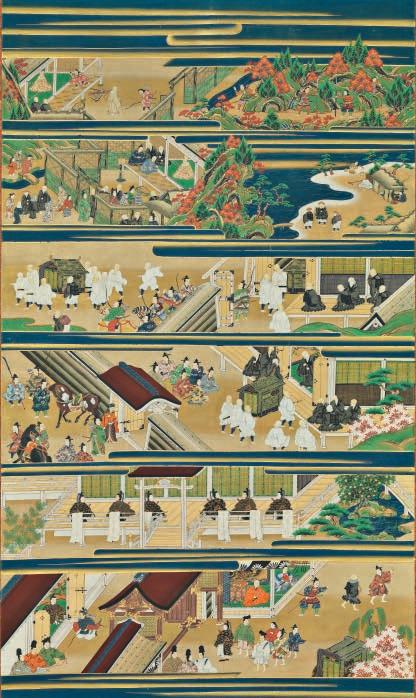

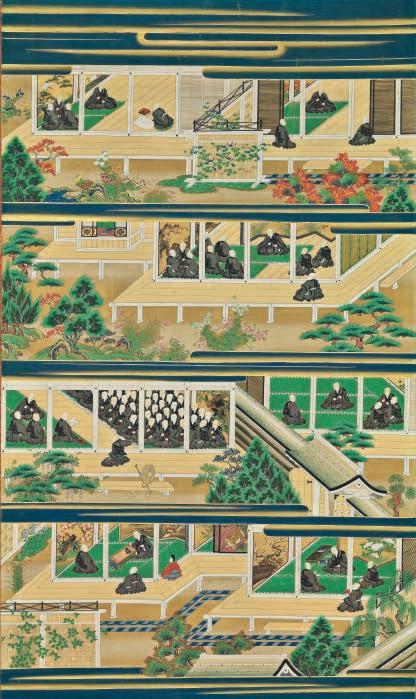

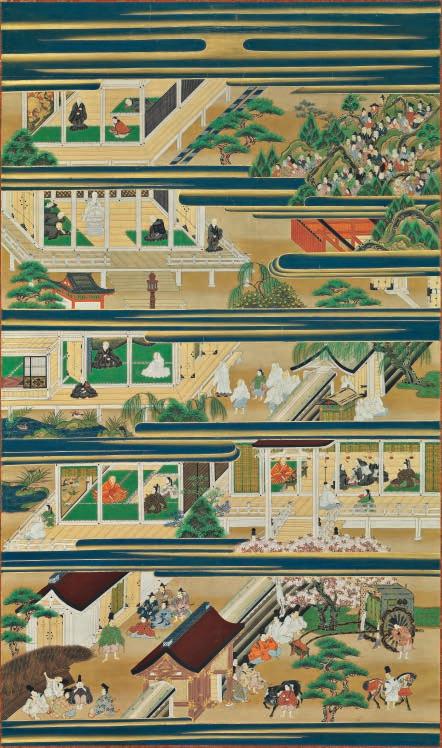

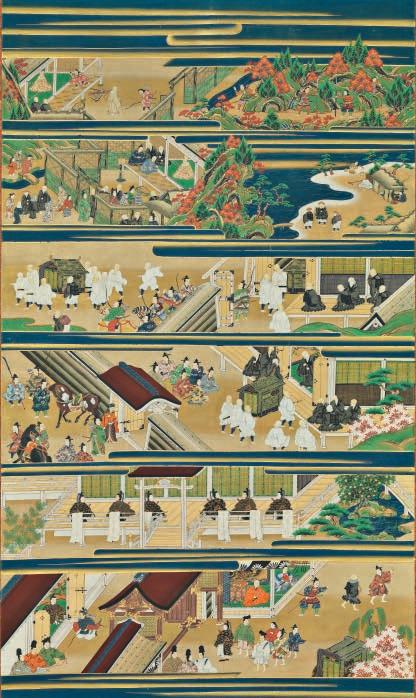

35 The Illustrated Life of Shinran Shōnin Japan

Edo period, 1699

Four hanging scrolls; ink, color and gold on silk

Each, H. 53⅛ x W. 31½ in. (135 x 80 cm)

John C. Weber Collection

The Buddha Shaka’s life is a model for those who pursue enlightenment. Shinran (1173–1263) is the celebrated founder of Japan’s True Pure Land sect (Jōdo Shinshū) of Buddhism. This teaching stresses the adherent’s awakening to his karmic reality as an unenlightened being, as well as his unconditional love of Amida, the Buddha of Infinite Light who lives in the Western Paradise. According to this model, Nenbutsu, the act of pronouncing Namu Amida Butsu (I take refuge in Amida) will ensure birth in the Pure Land and subsequent enlightenment.

This is one of many biographical illustrations dedicated to the life of Shinran mounted as a set of hanging scrolls. The narrative progresses chronologically from right to left, top to bottom. These sets were hung in temple halls during the annual memorial service commemorating the master’s death. The images enhanced the experience of those listening to a monk recite the story of Shinran’s life.

This set is remarkable for its excellent condition, attention to detail, and sumptuous application of gold and bright color. The scenes are all shown from

a bird’s- eye perspective. The artist devoted careful attention to the individualization of textile designs and elaborate articulation of paintings on folding screens, many with gold and bird-and-flower imagery placed here and there in the interiors. Gold pigment enhances rocks, hills, and clouds in the landscape. Tiny dots of white shell-powder gesso relief (gofun) give blossoms on the trees a sense of threedimensionality. The artist has also been careful to give each finely painted face individual characteristics. AP

Photography Credits

The images appear courtesy of the following sources. Every effort has been made to credit the photographers and the sources; if there are errors or omissions, please contact Asia Society Museum so that corrections can be made in any subsequent edition.

Fig. 1: Modified from Y. Hōjō, “Yukinoyama kofun no sekiseihin” (Stone artefacts in the Yukinoyama Tomb). In Yukinoyama kofun no kenkyū, kōsaihen (Yukinoyama tomb research: Essays), edited by Yukinoyama Kofun Hakkutsu Chōsadan, 309–50. Osaka: Osaka University Department of Archaeology, 1996; figs. 2, 3: Photo: Brooklyn Museum; fig. 4: Photograph © 2020 Museum of Fine Arts, Boston; cat. nos. 1, 6, 8, 10, 12, 14, 15, 18, 19, 20, 28, 33, 52, 64: Photography courtesy of John C. Weber Collection; cat. nos. 2, 5: Photography by Steven Tucker, courtesy of John C. Weber Collection; cat. nos. 3, 11, 22, 23, 24, 25, 27, 29, 31, 42, 43, 47: Photography by Synthescape, courtesy of Asia Society; cat. nos. 4, 7, 9, 13, 16, 17, 21, 26, 30, 32, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 44, 45, 46, 48, 49, 50, 51, 53, 54, 55, 56, 57, 58, 59, 60, 61, 62, 63, 65, 66, 67, 68: Photography by John Bigelow Taylor, courtesy of John C. Weber Collection.

208

Melinda Takeuchi

Melinda Takeuchi