WONDERFUL WHISKIES d d

Dear reader, There has been something on my mind for a while now, so I have to get it off my chest.

In my previous whisky book, which also happens to be called The Whisky Book, I talked extensively about ‘our nose’ as an instrument for enjoying whisky. If you have read it, you will surely have noticed that in that particular chapter, ‘Ode to the Nose’, I suddenly departed from my usual matter-of-fact writing style and suddenly used unbridled melodious language. With a series of adjectives and many vowels, I sang the praises of the olfactory epithelium, with its 30 million receptors that analyse all the odours that pass through and send them on to the brain. That, in turn, enables us to distinguish 10,000 aromas.

Well, I would like to apologise for that.

First of all, that epithelium is the size of a postage stamp. A STAMP. With ‘30 million receptors’? Not 30,249,718? No, ‘30 million’ — a round figure, a three followed by seven zeros. I should have known such a nice round number is not possible. And 10,000 aromas? What use is that? Can you even name 40 aromas?! Try and do it that right now... Don’t worry; I can’t, either. Our noses make me laugh.

By the way, even the Creator must not have believed in our noses. He gave us two eyes, two ears, two hands... you name it. Two of everything. But noses? Just one. And the nose is something that is often in the way. If it’s not sneezing, it’s blocked. Rubbish.

Belgium, a tiny country, has 30 clinics specialising in rhinoplasty. Not surprising. The ancient Sanskrit book Sushruta Samhita already described rhinoplasty in 600 B.C., which says it all. And then there’s this: if our nose is so important for enjoying whisky, why don’t I know of any whisky that glorifies the human nose in its name?

Pig’s Nose is a Scottish blend, five years old, 60% grain alcohol from Invergordon and 40% malt from Speyside, Islay and the Lowlands, well blended and matured in first-fill ex-bourbon casks.

The blend has been around since 1977 and (along with the blended malt Sheep Dip) changed hands a few times until it finally fell to Ian Macleod. The bottle still features a pig triumphantly sticking its nose up. ‘As smooth and soft as a pig’s nose’ is written in large letters. You see, that makes me angry again. As if the pig’s nose is only smooth and soft. Their nose is, damn it, better than ours.

In their book The Ubiquitous Pig, Marilyn Nissenson and Susan Jonas stand up for the cute little rascals (what a lot of reading one has to do to write a scientifically based whisky book!): ‘After the dog, the pig is the most kept pet in the world. It is intelligent, loyal,

obedient, clean and sweet. Like man, they chew their food only once, but unlike man, the pig never overeats. They are gourmets, thanks to their highly developed sense of smell. In a study in the U.K., scientists served 200 different vegetables and plants to some hungry pigs. Just by smelling, the pigs refused 117 of them.’

Now that’s quite something, isn’t it?

Does this detract in any way from enjoying a ‘wee dram’ of Pig’s Nose? Not at all. I like Pig’s Nose.

But one thing is crystal clear: stop sniffing your whisky glass. It’s not only ridiculous; it’s also wholly useless... what our nose extracts is nothing special.

But don’t worry: as always, I have a solution that promises to amaze you.

At the University of Technology in Sydney (UTS) in Australia, a surprising electronic device was developed in 2019 and first described in the scientific journal IEEE Sensors Letters: the NOS.E.

It was first demonstrated in 2020 at CeBIT Australia, a fair to promote current and future technologies. The device contains eight gas sensors that mimic the human olfactory system but greatly surpass its sensitivity. You throw a wee dram in the NOS.E, and a series of algorithms and artificial intelligence spring into action in no time. Endless tables are consulted, and then the NOS.E instantly tells you everything there is to know about the whisky.

What’s more, you know immediately with almost 100% certainty where that whisky comes from, with 96.15% certainty how old it is, with 92.31% certainty what type of whisky it is (blended, single, etc.). It also tells you in detail what you smell and taste.

London, seventeenth century

On the eve of 14 July, 1618, John Taylor, better known as the ‘Water Poet’, closed the door of the Bell Inn pub near Aldersgate on the north side of London, mounted his horse, and set off ‘with the wind from the south’ for a three-month tour of England and Scotland.

No mean feat in 1618! The roads were somewhat unpredictable once away from London. And in Scotland, they were virtually non-existent. He was accompanied by a few patrons and knew a few people along the way. And that was just as well, for he left without a single penny in his pocket: ‘neither Begging, Borrowing, or Asking Meate, drinke or Lodging’. He recorded his experiences in his diary, ‘The Penniless Pilgrimage’.

It was not his first exploit. He earned his living by running a ferry service on the Thames, hence his pseudonym: ‘The Kings Majesties Water Poet’. He got the idea of sailing down the

Thames from London to Sheppey in Kent (about 65 kilometres) in a paper boat. He recorded the result in a moving poem:

…The water still rose higher by degrees, In three miles going, almost to our knees. Our rotten bottom all to tatters fell, And left our boat as bottomless as hell. His pilgrimage, fortunately, ended better, even though his horse was ‘neither stallion nor mare, but a castrated sluggard’. But what interests us most is what he took with him on his road. He lists it in verse, but it comes down to this: lots of rusks, cheeses with fruit, salted bacon, beef tongue, oil and vinegar. He did not have a high opinion of Scottish cuisine because he also carried a lot of mithridate, a mythical medicine containing 65 ingredients

that provided proper protection against poisoning. And to complete his ‘indispensable’ luggage: plenty of aqua vitae, whisky, which he describes in one fell swoop as ‘that sweet Ambrosial Nectar, the potion of the gods’.

What a compliment! ‘Ambrosia’ with a capital A. Penelope took Ambrosia before she appeared before her admirers for the last time. Homer wrote: ‘All traces of age had disappeared, and her admirers were inflamed with passion at the sight of her beauty’. They all blushed because Penelope is still praised for her virtue and loyalty to her husband Odysseus (the creator of the Trojan horse). If anyone got nasty, she would bite their hands and, if we are to believe Homer, several Greeks lost their fingers.

‘Whisky as Ambrosia.’ It’s excellent to hear that from an Englishman. But then the question also arises: why would an Englishman take ‘enough whisky’ to Scotland?

There was much drinking in England and Scotland in the seventeenth century. In Scotland, it was often limited to beer, sack (the Spanish fortified wine, the forerunner of sherry), white wine and claret, a red wine from Bordeaux. Whisky was usually only consumed on festive occasions, especially funerals. And particularly in the Scottish Lowlands and the islands, where they dragged all the spare grain — barley, oats, wheat — to their (illegal) distilleries. Even our ‘Penniless Traveller’ John Taylor reports that he could quietly enjoy ‘plenty’ of whisky at a funeral.

Taking aqua vitae with him was an excellent idea. Even the English who travelled with him were happy with this supply. At home, they stuck mainly to ale, beer and wine. According to some sober historians, the Norman William the Conqueror defeated the English at Hastings in 1066 mainly because a large number of the English fighters were drunk. Six hundred years later, things had not improved.

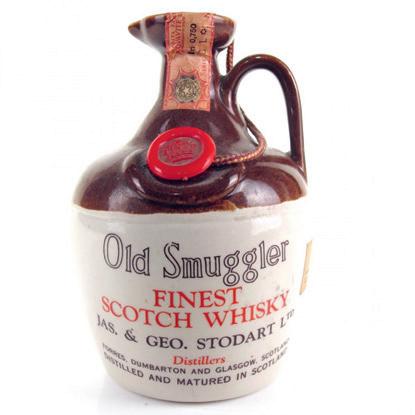

Above Moominpappa’s bed hangs a large poster depicting a vast bottle of Haig whisky. I know this because the fictional children’s character wrote it in his ‘memoirs’. Moominpappa made many extraordinary journeys (on land, at sea and in the air) and survived almost every natural and supernatural threat that could occur. And he kept meticulous records. You might conclude that Moominpappa is a lover of fine whiskies, and this is true, but if you think that ‘Don’t be Vague... ask for Haig’ is his favourite whisky, then you are wrong. His preference was and still is for the Scottish blend Old Smuggler..

The Swede Moominpappa, who always wears a black top hat, is the husband of Moominmamma. Together they have a child: Moomintroll. They live in Moomin Valley (I’ll stick to the English names, it gets too tricky in Swedish). As you might suspect, they are

trolls. White trolls. So not the ugly devil-like creatures they used to show us when we were young. They look more like a pot-bellied hippopotamuses on two legs. They have about 40 friends. They are not trolls. Some look like animals, and others belong to the Mymbles, whatever that means. You don’t always know if they are boys or girls. They have fun Swedish names like Snusmumriken, Snorkfröken, Hattifnattar, Bisamråttan, Tofslan and Vifslan. Those last two are thorns in the side of worried parents. They are called Thingumy and Bob in English, but it is clear (despite the ‘Bob’) that they are girls. And they are in love with each other — they’re a lesbian couple.

There we go. We already had the issue of the father drinking whisky, and now this. In children’s books! Read aloud from six years of age, self-read from nine it says on the cover. Well done!

But it gets even better with Stinky, a born criminal and dangerous cheat. Or another character whose name escapes me now prides himself on having wiped out a whole colony of ants. In short, evil seeps through these stories. And nowhere is this expressly condemned. What sick mind thought up this pernicious stuff?

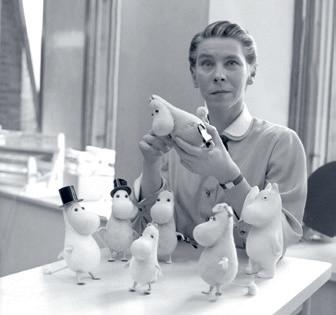

Tove (or ‘Toeve’) was born in Helsinki in 1914, when Finland was still part of the Russian Empire. Her parents lived in the Swedish-speaking part of the country. At a very young age, Tove proved to be very talented. She would go down in history as an author of novels and comics, a painter and an illustrator. But it was mainly her children’s books that made her world-famous. In Scandinavia, people mentioned her in the same breath as Astrid Lindgren, the spiritual mother of Pippi Longstocking.

She invented the whole Moomin family and their wacky friends in 1945 and wrote nine Moomin stories. This was followed ten years later by comic strips (which she also published in English) and, around 1990, by a series of TV films that immediately won the hearts of the Japanese.

It is hard to find whisky and other worldly sins in her first books, but in the comics and films (and through Japanese supplements), we see the elements that make hard-core conservatives raise their eyebrows. But her books are somewhat autobiographical. She was an adventurer who lived for a long time on a desert island, which comes across in her stories. The fact that she was a lesbian influenced the creation of ‘Tofslan and Vifslan’. Tove Jansson died in 2001. But her Moomins are immortal. Her books have been translated into many languages.

Mackmyra, founded in 1999 and thus Sweden’s ‘oldest’ distillery, released a limited-edition Old Smuggler Whisky in 2014, 100 years after Tove Jansson’s birth. There was no better way to celebrate that birthday than with a bottle of Old Smuggler for Moominpappa. They

Stepping into the bonded warehouse of a distillery and, amid the long rows of richly filled casks, inhaling the scent of the ‘angels’ share’ is an unforgettable moment for any whisky lover. On the evening of Friday, 20 May, 2011, I got a completely different view of Glenfarclas’ Warehouse 14. The whisky smell was still there, but there were no casks. They were temporarily replaced by colourfully decorated and elegantly set round tables. The otherwise grey walls were draped with red and white cloths, and almost fairy-like lighting gave the setting a very festive character.

Outside, the Dufftown Pipe Band ensured that everyone found their way to warehouse 14 without any problems, while inside, the Glencraig Scottish Dance Band created the perfect atmosphere. It was a party, and more than 300 guests had come to Ballindalloch.

And, of course, a whisky party like this needs a party whisky. For distilleries and bottlers, any occasion is a good reason to release a party whisky, a nice collector’s item. You can find them in all possible strengths!

Glenfarclas distillery pegs its birth year at 1836, even though there are several reasons to believe it is much older. But there is virtually no evidence of that. In 1836, a ‘down-toearth’ Scot, Robert Hay, made the wise decision to apply for a licence for his stills near Ballindalloch Castle in north-east Scotland and attached the name Glenfarclas to it.

Thirty years later, Robert Hay unexpectedly left for the eternal hunting grounds, and one John Grand took over the business. Glenfarclas has remained in the hands of the Grand family to this day. So, in 2011, they had every reason to celebrate and bring a unique party whisky on the market: the ‘Glenfarclas 175’, the bottle with the black label in a retro case.

It became a blend of 16 casks from the last six decades of the twentieth century, the oldest of which was from 1952. George Grand himself chose them all. They filled 6,000 bottles at 43% abv, which were sold in no time.

Out of necessity, a second ‘Festival Single Malt’ followed: Glenfarclas 175 Chairman’s Reserve. For this, they chose four casks from before 1960, two from 1965, one from 1966 and one from 1969, which together were precisely 175 years old. Just enough to fill 1,296 bottles at 46% abv. You will recognise them by the classic red-yellow label and red and black print. They came in a red case with a dated glass and a water jug.

It is a ‘well-kept’ secret (logically, otherwise it would no longer be a secret) that there is also a third Glenfarclas 175: the ‘Glenfarclas 175 Ceilidh’. My Taiwanese table neighbour at the party had read the word ‘ceilidh’ on his invitation and asked if I knew what that dessert was. When I explained to him, as colourfully as possible, that he was going to see a typical Scottish dance party, where the dancers, apparently unrehearsed, would form dancing figures without bumping into each other, he looked at me in disbelief. I told him this was an offshoot of the dance parties held at the French court. He said something in Chinese to his companion, and they both looked at me incredulously. ‘Boring?’ he asked doubtfully. My smile told him all he needed to know. When the bottle of Glenfarclas 175 Ceilidh came out for dessert, he patted me on the back as if to say, ‘You were kidding, huh!’ I didn’t see him on the dance floor later.

The Glenfarclas 175 Ceilidh is an 18-year-old single cask from a refill sherry cask. John Grand selected it. They bottled only 200 bottles at 55.5% abv. The information on the label has deliberately been kept sparse; it is a ‘secret bottle’ after all. We know from a reliable source that 58 bottles were poured at the party. Furthermore, each staff member received a bottle (that’s another 38). The foreign distributors and guests who

Whisky is back with a vengeance. This book does not contain a list of taste patterns and distilleries, but hilarious tales full of special anecdotes about the most ‘beautiful’ and ‘luxurious’ bottles. Juicy stories, ideal to pair with a delicious glass of single malt!

For almost forty years, whisky devotee Fernand Dacquin has been traveling through this wonderful whisky world, in search of the most striking stories and images. He bottled 40 stories about famous whiskey bottles, in his humorous style.

Wonderful Whiskies is funny, surprising and the ideal gift for the whisky lover.

www.lannoo.com