5 minute read

THROWING THE BABY OUT WITH THE BATH WATER

Forty-year veterans in our schools can’t recall a time when public education wasn’t the object of unrelenting criticism. A school superintendent who retired a few years ago told me that, from the day she entered the classroom, her entire career in education had been spent amidst public complaints about school performance.

Advertisement

The criticisms come in two parts, one clearly unjustified. That criticism is that public education is failing across the board. Putting the nation at risk, in fact. That’s demonstrably not true.

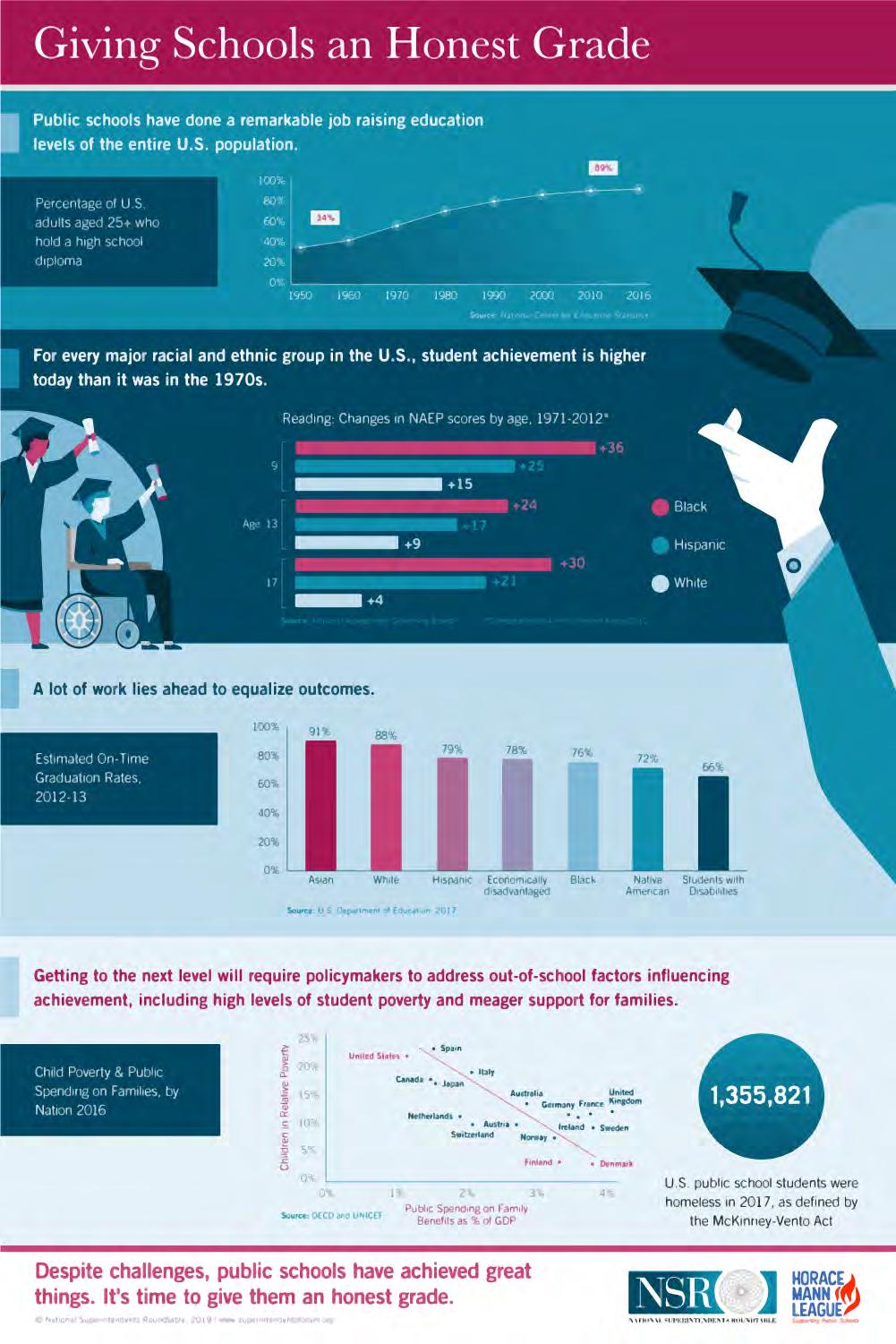

On the next page, you’ll see an infographic from the National Superintendents Roundtable and the Horace Mann League. It makes clear that public education is one of the great success stories of the United States.

Consider: only 34 percent of young adults had a high school diploma in 1950, compared to nearly 90 percent in 2016. Graduates can’t read? Nonsense. Every major racial and ethnic group, at ages 9, 13, and 17, is scoring higher on recent NAEP reading achievement tests than they were in 1971. (The same holds true for mathematics).

But there exists a justified criticism. It revolves around equity.

As the infographic also demonstrates, we have a lot of ground to make up if we want to equalize outcomes. While around 90 percent of Asian and White students graduate on time, the proportion declines precipitously when students of color, the poor, and those with disabilities are examined.

The on-time graduation rates for Hispanics (79 percent), economically disadvantaged students (78 percent), African-American (76 percent), Native American (72 percent) and students with disabilities (66 percent) are shockingly low, a consequence of a combination of structured discrimination within the school system and government abandonment of the communities in which many of these students live.

So, we find the fourth major component of the infographic focused on out-of-school factors that require attention. The United States is almost off the international charts in terms of high levels of student poverty and low levels of support for families with children. Where do we find Finland, often held up as a model for what our schools should accomplish? Why, off the charts in the other direction—generous levels of support for families and very low levels of student poverty.

But there is a danger that in responding to the legitimate complaints of leaders of communities of color and the poor that “reformers” with their proposals for vouchers and charters will throw the baby out with the bathwater. It’s the special needs of special populations that require focused attention.

We shouldn’t pretend this is easy but meeting those needs will not be accomplished without honestly addressing the dimensions of the challenge.

Discrimination within the school system

As the endless parade of school finance suits demonstrates, one part of the challenge is that more resources, financial and human, are typically directed toward students in the most affluent communities than toward students in low-income neighborhoods.

That seems to be true in comparisons between districts in the same state and in comparisons between schools in the same district. Within individual schools, also, it is not uncommon for the more advantaged students to have greater access to more experienced teachers and more demanding curriculum than low-income students and students of color.

Some years ago, the Roundtable held a conference on opportunities within schools, at which a highly impressive young African-American graduate recalled locating an Advanced Placement class buried practically in the school attic. When he walked into the classroom the teacher greeted him with, “How did you know about this class?”

Structurally according to Government Accountability Office, nearly three-quarters of schools in more affluent communities offer Advanced Placement classes; less than half of schools in racially and economically isolated communities do. There’s a lot of work to be done in the schools.

Discrimination outside the school system

Those challenges within the system pale in comparison to community challenges. There seems to be little doubt that the conditions

under which some children live stunt their development and leave them too traumatized to learn.

In some communities, said the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching’s Anthony Bryk (following 15 years of research on school improvement in Chicago), the “density of problems walking through the front door is so palpable every day, it virtually consumes all your time and energy and detracts from efforts to improve teaching and learning.”

What are these problems? Among them:

POVERTY

More than 50 percent of students in American public schools are low-income, according to the Southern Education Foundation.

CONCENTRATED POVERTY IN COMMUNITIES OF COLOR

About 16 percent of schools in the United States are both high-poverty and high-minority enrollment (i.e., with 75 percent of students in the school made up of students of color AND eligible for free and reduced-price meals).

Paul A. Jargowsky, director of Rutgers University’s Center for Urban Research and Education, told the Roundtable that patterns of gentrification and exclusionary zoning have exacerbated neighborhood segregation, encouraged unbridled suburban development, creating a “durable architecture of segregation.” Recent research argues that “de facto” segregation in the North was not an accident but the consequence of federal, state, and local practices that included exclusionary zoning, “redlining” that denied housing to families of color in many communities, denial of mortgages, and even federal loan guarantees to builders premised on the explicit condition of prohibiting sales to African-American buyers.

Perhaps not surprisingly, the achievement gap between students from high- and low-income families is about 40 percent larger for students born in 2001 than it had been for those born 25 years earlier, according to Sean Reardon of Stanford University.

What needs to be understood is that truckloads of research dating back to the seminal “Coleman report” in the 1960s demonstrates the out-of-school factors account for somewhere been 70 and 80 percent of tested student achievement.

“Reformers” can keep tinkering with ersatz solutions such as charters, vouchers, and tests and accountability. But, until U.S. policy begins to respond to the Third World conditions in which too many American children are being raised, dramatic improvements in student outcomes are likely to be hard to find.

James Harvey is executive director of the National Superintendents Roundtable. Follow NSR on Twitter at @natsupers.