5 minute read

MAPPING THE MENU

from National Culinary Review (September/October 2024)

by National Culinary Review (an American Culinary Federation publication)

MAPPING THE MENU

How to maximize equipment and kitchen design by analyzing menus

By ACF Chef Ray McCue, CEC, AAC

Everything starts with the menu. It is the primary marketing and sales tool of the establishment. It’s also the first step in identifying the core culinary and target market values. The menu is a standalone ambassador for your brand, giving customers the first perception of what the restaurant is all about. Perhaps even more importantly, the menu dictates much about how the operation will be organized and managed, and how the kitchen should be designed, constructed and equipped.

Professional foodservice consultants and kitchen designers, like chefs, always start by understanding the menu. In this day and age, consumers are looking for more variety when they dine out. The goal is to offer a variety of menu items that touch on a diversity of preferences and feature different textures, temperatures, cooking techniques and preparation methods. That can make designing a kitchen even more challenging and complex.

One of the most common problems in kitchen operations is when a chef overloads one particular kitchen station or piece of equipment with the preparation of too many menu items. Long ticket times are a widespread problem in foodservice operations, and nothing will deter potential and regular customers more than having to wait 45 minutes or more to get their food.

MENU-MAPPING

The best way to avoid overloading a station or equipment is to conduct what

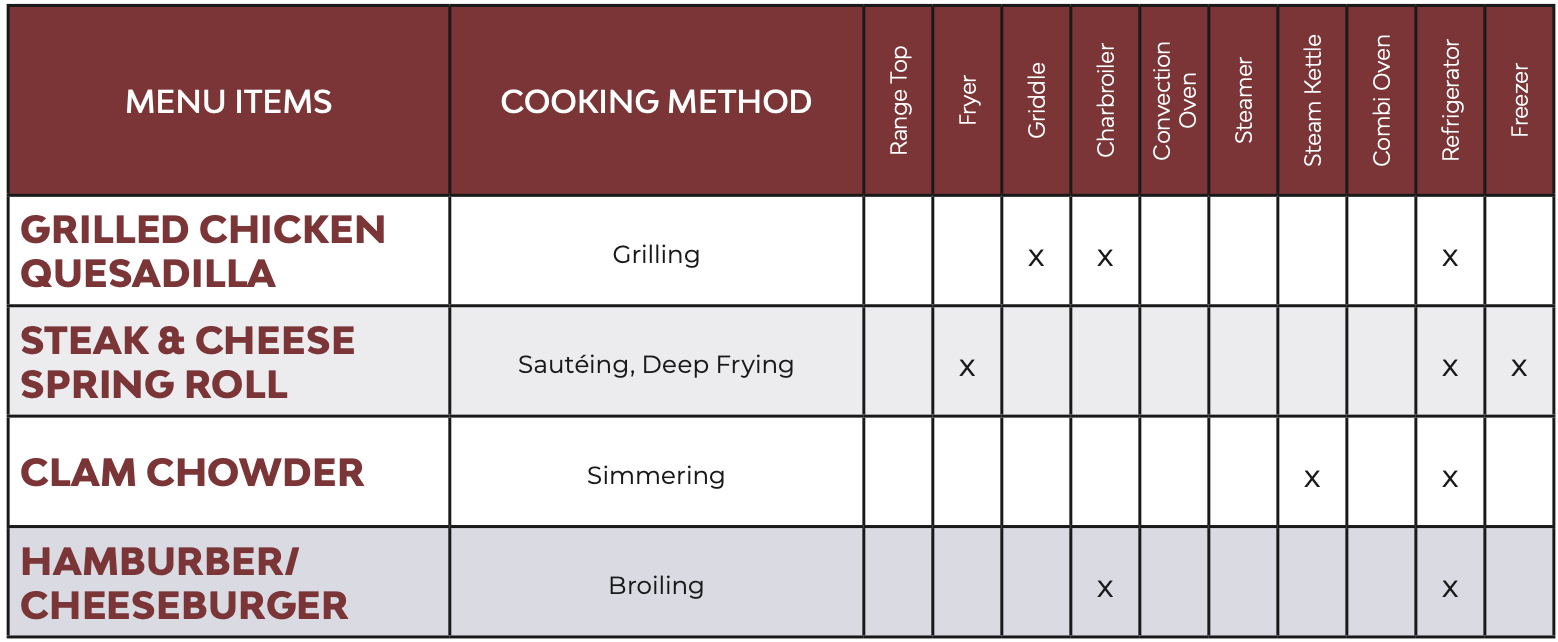

I like to call (and what I teach my students) menumapping. Menu-mapping involves visually identifying which menu items require which equipment and supplies through spreadsheets, charts or other tools. It helps chefs reduce bottlenecks and enhance efficiencies in their operations. It’s almost like putting a puzzle together and moving pieces around when they don’t quite fit.

For example, if a restaurant has British-style fish and chips on the menu, a fryer would certainly be needed. But a chef who has menu-mapped would realize two fryers are needed: one for the fish and the other for the chips. Or, take a grilled chicken quesadilla as another example. That dish typically would require the use of a flattop, but also a grill, as the chicken needs to be grilled before it goes into the quesadilla. And then there’s the refrigeration required for all the cheese and other ingredients.

In my class, when teaching menu-mapping, I present students with an existing menu from an owner-operator and ask them to map out the cooking methods, equipment needed and station usage for each dish. I have them list or check off in a chart each piece of large item line equipment necessary to produce each menu item. Too many checks in one station or for one type of equipment means more diversification in the cooking method is needed. When completed, analyze the total number of checks for each type of equipment item. The results should justify and direct the equipment selection, therefore influencing equipment and design decisions. Chefs have a propensity to overload stations and/or equipment based on their tastes or experience level, but the menu

must be diversified enough across the cookline to ensure a smoother operation. It’s important to select equipment based on the best quality cooking results, utility energy efficiency and human energy efficiency.

EQUIPMENT PLACEMENT

I also teach my students about proper equipment placement, should they be able to design their own kitchen or work with a designer in the future. For example, fryers should be located close to the cold or appetizer station since many of the fried items are also used in that area. If the menu requires specialized equipment such as woks, rotisseries or brick pizza ovens, it’s best to position them on the end of the cooking line so they’re easier to replace with other equipment if the menu changes. Also, positioning countertop equipment on refrigerated bases allows easy interchange of equipment. For ranges, I suggest using equipment that is built with modular sections so the top or bottom can easily be changed in the field to accommodate last-minute menu updates or individual preferences. Modular sections can be changed after the unit is operational.

Sometimes, chefs have to make do with what a kitchen designer has designed without their input. In

that case, the menu needs to be designed with the physical kitchen constraints in mind. The chef must reverse-engineer the menu. In other words, based on the given factors and equipment provided, what menu items would allow you to crossutilize equipment and not overburden certain stations?

Menu-mapping merges culinary operations expertise with facility management skills. I strongly believe culinary students (and professional chefs) should know the basics of good kitchen design and how to maximize and maintain their equipment so they’ll make the right purchases and know how to talk to technicians when appliances break down. More importantly, menumapping is the key to seeing the bigger picture and being able to make the right tweaks to menus and operations to ensure the highest level of efficiency, and ultimately, success.

ACF Chef Ray McCue, CEC, AAC, is an associate professor at Johnson & Wales University in Providence, R.I., and a member of the ACF board of directors as vice president of the Northeast Region.

Click here for more stories from the Sept/Oct 2024 issue of National Culinary Review, published by the American Culinary Federation.