10 minute read

The Secession Winter

By John Coski

The now-famous headline of the December 20, 1860, Charleston Mercury Extra screamed: “The Union is Dissolved!” The South Carolina convention’s unanimous vote to approve an ordinance of secession a month after Abraham Lincoln’s election as U.S. president was no surprise; it was in fact the culmination of decades of discontent within the Union.

The suspense of the moment was the anticipation of what would happen next. In its call for a secession convention, South Carolina’s legislature confidently invited other seceding states to meet in Montgomery, Alabama, in February. But would other states actually follow South Carolina’s lead, or would she find herself acting alone as she had on other occasions?

The “Secession Winter” that South Carolina initiated was a time of decision not only for the states but also for individuals. People of every class, race, and gender had a stake in the crisis of the Union and would someday confront a decision of what to do if and when their state seceded. Others did not wait passively, but sought to help shape events.

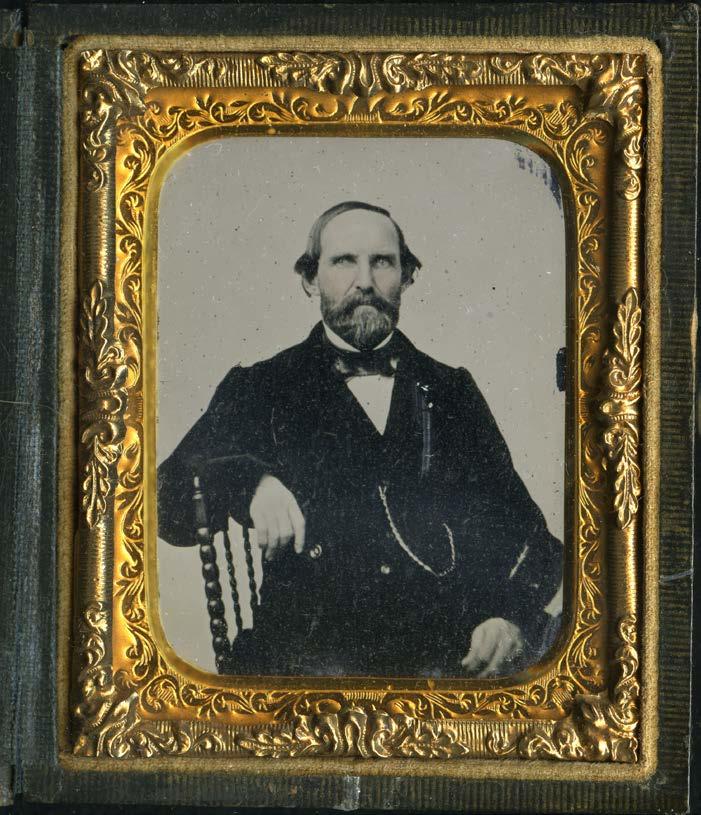

BEN MCCULLOCH was born in Tennessee and followed his neighbor, Davy Crockett, to Texas and became one of the Lone Star Republic’s luminaries. He fought for Texas independence alongside his friend and commander, Sam Houston, fought with distinction in the Mexican War, and served as a Texas Ranger and U.S. marshal.

As the political crisis deepened late in 1860, McCulloch and Houston parted ways. Houston adamantly opposed secession; McCulloch traveled through the South gauging political sentiment and whipping up enthusiasm for secession.

On November 25, 1860, McCulloch wrote to his brother Henry from Columbia, South Carolina:

"I wrote to you from the capitol of Ga. & enclosed you a copy of a letter I wrote Genl Houston asking him to call the Legislature of Texas together, fearing he would decline to do so, I have since written a letter to John Marshall the editor of the Gazette, urging him to call the people in each county in our State to call primary meetings and through them a convention, in the event of the Legislature not be[ing] convened by the Gov. This is the only way to have action, let no time be lost, or Texas will be behind every southern State that makes cotton.”

“Great events are now about to transpire,” McCulloch reported from the epicenter of Secession. “The union will be dissolved. It is already dissolved. [T]his State needs but the formal action of a convention to consummate & give publicity to what has been done. There will not be a single voice in that convention (when it meets) raised in behalf of submission or the union….Other States will follow rapidly.

SOUTH CAROLINA’S SECESSION on December 20th and the expectation that other deep south states soon would follow her lead confronted southern-born U.S. military officers with the dilemma of loyalty. For some, the dilemma was vexing; for others, such as South Carolinian Barnard Bee, the choice was clear. On January 4, 1861, Bee wrote from Fort Laramie, Nebraska Territory (modern-day Wyoming) to his friend and fellow soldier, Henry Heth of Virginia:

"The storm clouds are gathering fast around us and we will soon have to take our stands, either to resist this fury, or submit to their violence— I am sorry you are not with your company—I want the whole south to go together, having first stated firmly but courteously to the northern states their ultimatum on slavery—this being rejected the Southern Confederacy would embrace every southern state and would be magnificent—Then the Southerners in the Army and Navy should bring all they can with them….If you are in Washington see Mr. Davis and get him to express an opinion as to the question whether or not the Secession of the Southern states is not de facto dissolution and absolves Army & Navy from Allegiance—Such is my view and I would like it to be sustained by high authority so as to aid me in bringing men and material South…."

A former soldier from South Carolina, Daniel Harvey Hill, had a civilian’s perspective on the crisis of the Union. From his home in Charlotte, North Carolina, Hill on January 15, 1861, wrote to a northern creditor lamenting the unsettling effects that political events were having on everyday financial matters.

"I am very desirous to settle our account, but exchange is now enormous and I would rather pay interest than be subjected to the loss through discount. Will you take a check on one of our banks? If not, charge us interest, and wait until our new Republic is formed, or make some arrangements for the exchange."

If the political situation had left the financial markets uncertain, Hill himself suffered from no uncertainty in his assessment. “I have told you all along that our people would not submit to Black Republican rule,” he went on to explain to his creditor, whom he addressed a “My Dear Friend.”

"We will not have a party to reign over us, who have sought in every way in their power to foment insurrection & murder…How long would you people consent to a union with us, if we sent agents and emissaries to poison your families and incendiaries to burn your towns and villages? Bring these matters home to yourselves, and ask yourselves in the presence of God if the South is not right in her determination to resist to the last extremity."

Although he betrayed an obsession with the Republican Party’s avowed hostility to slavery, Hill did not regard the issue about slavery, per se, but about defending his wife and children and resisting the domination of government by a party “whose avowed policy is murder.” By “taking up arms against the Black Republicans,” Hill explained, “I am engaged in the holiest of causes.”

BY THE MIDDLE of February 1861, six other states had passed ordinances of secession and their representatives has answered South Carolina’s summons to gather in Montgomery, Alabama. On February 8 th, the convention transformed itself into the provisional congress of the new Confederate States of America, adopted a provisional constitution, and selected a provisional president, Jefferson Davis of Mississippi.

On February 9 t h, a citizen of the new Confederate capital city wrote a letter to a northern business associate from what he called the “Republic of Alabama.” As had D.H. Hill, Mr. Lelland of the Montgomery Lumber Company noted how secession had disrupted the commercial relationships between southerners and northerners.

“[Y]our previous of the 4th enclosing our account and requesting an immediate answer has just come to hand and I am very sorry that I cannot respond to your bill just now, and have to claim your indulgence for a while longer,” Lelland began. “Since the election of Mr. Lincoln, business of all kinds has been brought to a complete stand still here[.] We have an investment of $60,000, now doing nothing, I find that it is the next thing to impossibility to collect anything at all.”

Although he went on to state that he had not intended “to write you a disunion letter,” Lelland could not refrain from laying his political cards on the table. “Everybody is busily preparing to resist any attempt that may be made by the incoming administration of the Old United States to coerce us back into submission,” he wrote. “Let us go in peace all will be right if not, to the victor the spoils. As far as we are concerned, we prefer to be blotted out of existence rather than give up our rights or to be ruled by a sectional party, give us our rights that is all we ask, and to be let alone.”

Unlike other men, south and north, Lelland expressed confidence that the obstacles to resumption of normal sectional relations were not insurmountable. “I am in hope that Mr. Lincoln will not attempt the folly of trying to whip us into the union, and that our difficulties will be settled on the 4th of March” —the day of Lincoln’s inauguration— “and that friendly relations shall again become established and that we will continue to trade with each other, as any other two foreign nations that are at peace with each other.”

One person in Montgomery who was not as optimistic about peace arrived a week after Lelland wrote his letter, In a February 20 th letter to his wife, he described Montgomery as “gay and handsome town of some 8000 inhabitants and will be not an unpleasant residence—As soon as an hour is my own I will look for a house and write to you more[.]”

That man was, of course, Jefferson Davis. He had received from the new Confederate Provisional Congress a summons to Montgomery to serve as the new nation’s provisional president. Davis described the audience for his February 18 th inauguration as large and brilliant. “[U]pon my weary heart was showered smiles plaudits and flowers,” the new president wrote, “but beyond them I saw troubles and thorns insurmountable. We are without machinery, without means and threatened by powerful opposition but I do not despond and will not shrink from the task imposed upon me[.]”

As Davis prepared to govern the Confederacy, and Abraham Lincoln prepared for his inauguration on March 4th , they and others knew that a Secession Winter was likely to thaw into a spring of armed conflict. That conflict began as Confederate batteries fired at Fort Sumner, where Major Robert Anderson had moved his small garrison on the day after Christmas. Other soldiers, including Ben McCulloch, Barnard Bee, and D.H. Hill, were preparing to fight that war. McCulloch and Bee were to die in action before the war was a year old. END

--------Dr. John M. Coski served as the museum’s historian and director of the Eleanor S. Brockenbrough Library for more than 30 years.