17 minute read

A Time for Heroes

Memorial Day A Time for Heroes

By Nancy Sullivan Geng, Inver Grove Heights, Minnesota

I leaned against an oak at the side of the road, wishing I were invisible, keeping my distance from my parents on their lawn chairs and my younger siblings scampering about.

I hoped none of my friends saw me there. God forbid they caught me waving one of the small American flags Mom bought at Ben Franklin for a dime. At 16, I was too old and definitely too cool for our small town’s Memorial Day parade. I ought to be at the lake, I brooded. But, no, the all-day festivities were mandatory in my family.

A high school band marched by, the girl in sequins missing her baton as it tumbled from the sky. Firemen blasted sirens in their polished red trucks. The uniforms on the troop of World War II veterans looked too snug on more than one member.

“Here comes Mama,” my father shouted.

Five black convertibles lumbered down the boulevard. The mayor was in the first, handing out programs. I didn’t need to look at one. I knew my uncle Bud’s name was printed on it, as it had been every year since he was killed in Italy. Our family’s war hero.

And I knew that perched on the backseat of one of the cars, waving and smiling, was Mama, my grandmother. She had a corsage on her lapel and a sign in gold embossed letters on the car door: “Gold Star Mother.”

I hid behind the tree so I wouldn’t have to meet her gaze. It wasn’t because I didn’t love her or appreciate her. She’d taught me how to sew, to call a strike in baseball. She made great cinnamon rolls, which we always ate after the parade.

What embarrassed me was all the attention she got for a son who had died 20 years earlier. With four other children and a dozen grandchildren, why linger over this one long-ago loss?

A teenager learns the importance of war veterans.

I peeked out from behind the oak just in time to see Mama wave and blow my family a kiss as the motorcade moved on. The purple ribbon on her hat fluttered in the breeze.

The rest of our Memorial Day ritual was equally scripted. No use trying to get out of it. I followed my family back to Mama’s house, where there was the usual baseball game in the backyard and the same old reminiscing about Uncle Bud in the kitchen.

Helping myself to a cinnamon roll, I retreated to the living room and plopped down on an armchair.

There I found myself staring at the Army photo of Bud on the bookcase. The uncle I’d never known. I must have looked at him a thousand times—so proud in his crested cap and knotted tie. His uniform was decorated with military emblems that I could never decode.

“Remember how hard Bud worked after we lost the farm? At haying season he worked all day, sunrise to sunset, baling for other farmers. Then he brought me all his wages. He’d say, ‘Mama, someday I’m going to buy you a brand-new farm. I promise.’ There wasn’t a better boy in the world!”

Sometimes I wondered about that boy dying alone in a muddy ditch in a foreign country he’d only read about. I thought of the scared kid who jumped out of a foxhole in front of an advancing enemy, only to be downed by a sniper. I couldn’t reconcile the image of the boy and his dog with that of the stalwart soldier.

Mama stood beside me for a while, looking at the photo. From outside came the sharp snap of an American flag flapping in the breeze and the voices of my cousins cheering my brother at bat. “Mama,” I asked, “what’s a hero?” Without a word she turned and walked down the hall to the back bedroom. I followed.

She opened a bureau drawer and took out a small metal box, then sank down onto the bed.

“These are Bud’s things,” she said. “They sent them to us after he died.” She opened the lid and handed me a telegram dated October 13, 1944. “The Secretary of State regrets to inform you that your son, Lloyd Heitzman, was killed in Italy.”

Funny, he was starting to look younger to me as I got older. Who were you, Uncle Bud? I nearly asked aloud.

I picked up the photo and turned it over. Yellowing tape held a prayer card that read: “Lloyd ‘Bud’ Heitzman, 1925- 1944. A Great Hero.” Nineteen years old when he died, not much older than I was. But a great hero? How could you be a hero at 19?

The floorboards creaked behind me. I turned to see Mama coming in from the kitchen, wiping her hands on her apron.

I almost hid the photo because I didn’t want to listen to the same stories I’d heard year after year: “Your uncle Bud had this little rat-terrier named Jiggs. Good old Jiggs. How he loved that mutt! He wouldn’t go anywhere without Jiggs. He used to put him in the rumble seat of his Chevy coupe and drive all over town.

Your son! I imagined Mama reading that sentence for the first time. I didn’t know what I would have done if I’d gotten a telegram like that.

“Here’s Bud’s wallet,” she continued. Even after all those years, it was caked with dried mud. Inside was Bud’s driver’s license with the date of his sixteenth birthday. I compared it with the driver’s license I had just received. A photo of Bud holding a little spotted dog fell out of the wallet. Jiggs. Bud looked so pleased with his mutt. Continued on next page >

There were other photos in the wallet: a laughing Bud standing arm in arm with two buddies, photos of my mom and aunt and uncle, another of Mama waving. This was the home Uncle Bud took with him, I thought.

I could see him in a foxhole, taking out these snapshots to remind himself of how much he was loved and missed.

“Who’s this?” I asked, pointing to a shot of a pretty dark-haired girl. “Marie. Bud dated her in high school. He wanted to marry her when he came home.” A girlfriend? Marriage? How heartbreaking to have a life, plans and hopes for the future, so brutally snuffed out.

Sitting on the bed, Mema and I sifted through the treasures in the box: a gold watch that had never been wound again. A sympathy letter from President Roosevelt, and one from Bud’s commander. A medal shaped like a heart, trimmed with a purple ribbon, and at the very bottom, the deed to Mama’s house.

“Why’s this here?” I asked.

“Because Bud bought this house for me.” She explained how after his death, the U.S. government gave her 10 thousand dollars, and with it she built the house she was still living in.“He kept his promise all right,” Mama said in a quiet voice I’d never heard before.

For a long while the two of us sat there on the bed. Then we put the wallet, the medal, the letters, the watch, the photos and the deed back into the metal box.

I finally understood why it was so important for Mama—and me—to remember Uncle Bud on this day. If he’d lived longer he might have built that house for Mama or married his high-school girlfriend. There might have been children and grandchildren to remember him by.

As it was, there was only that box, the name in the program and the reminiscing around the kitchen table.“I guess he was a hero because he gave everything for what he believed,” I said carefully.

“Yes, child,” Mama replied, wiping a tear with the back of her hand. “Don’t ever forget that.”

I haven’t. Even today with Mama gone, my husband and I take our lawn chairs to the tree-shaded boulevard on Memorial Day and give our daughters small American flags that I buy for a quarter at Ben Franklin.

I want them to remember that life isn’t just about getting what you want. Sometimes it involves giving up the things you love for what you love even more.

That many men and women did the same for their country—that’s what I think when I see the parade pass by now. And if I close my eyes and imagine, I can still see Mama in her regal purple hat, honoring her son, a true American hero.

Post 760 Adopts Secret Warrior’s Name By John Meyer

At its second meeting of 2020, the members of American Legion Post 760 in Oceanside, CA voted unanimously to name the post after charter member Doug “The Frenchman” LeTourneau who died suddenly July 25, 2019 in Texas. LeTourneau served three years in the Army during the Vietnam War, completing one tour of duty as a Green Beret in the secret war conducted far from the conventional war in S. Vietnam and media and Congressional and family knowledge.

A day later, LeTourneau and I drove to San Diego to record a podcast with retired Navy SEAL Lt. Cmdr. Jocko Willink. The interview was an outstanding success. This is the link to that interview: http://jockopodcast.com (See direct link below) It was posted July 17, 2019. A week later, LeTourneau passed away in Texas following a bout with heat exhaustion and a scorpion sting.

At a following Post 760 meeting I explained that LeTourneau was an Eagle Boy Scout raised in Van Nuys, CA, where he was president of the Future Farmers of America, competed in intercollegiate rodeo in high school and while attending Cal Poly, San Luis Obispo. On Sept. 1, 1967, one day after reading the book The Green Berets by Robin Moore, he enlisted in the Army and graduated from Special Forces Training Group in the summer of 1968.

John Meyer & Doug LeTourneau

Nov. 11, 2011 Gallatin, TN - Doug received the Purple Heart for wounds received in November 1968 while on a mission.

After Post 760 Commander Chuck Atkinson called to order the first meeting of the newly minted post in early 2019, I called LeTourneau to explain its unique origin and mission: To help fellow veterans, service members and families, to perform community outreach while always moving forward in patriotic efforts to honor our country. LeTourneau’s response was quick, and surprising: “Sign me up, I’m going to be moving out to Southern California to live with my sister soon and I want to be a part of an American Legion post that is proactive, not a post that sits around the bar all day telling lies and war stories. Sign me up.” Thus Doug and I became charter members of the new post.

I first met LeTourneau in October 1968 at the top secret MACV-SOG compound in Phu Bai, FOB 1. SOG was the eight-year secret war conducted across the fence in Laos, Cambodia and N. Vietnam. That unit sustained the highest casualty rate during the Vietnam War. Letourneau had volunteered to join fellow Green Berets in conducting clandestine top-secret missions far behind enemy lines without conventional artillery or ground support troops. It was the beginning of a long friendship and bond between the skinny 135-pound California cowboy and fellow SOG recon men at FOB 1 and later at CCN in Da Nang.

The year 1968 was a landmark year for the U.S. in Vietnam, it was the year of highest casualties both in conventional forces and among SOG recon teams and Hatchet Force troops. When I reported to FOB 1 in May 1968, there were 30 recon teams listed on base, by October, only a few were fully operational.

On July 8, 2019, we visited Post 760 in the spacious Veterans Resource Center in the Veterans Association of North (San Diego) County (VANC) at 1617 Mission Ave., in Oceanside, CA. When he walked in he was amazed at what he saw. “It’s one thing to see pictures of this building and where Post 760 meets,” he said, “but it’s another thing to actually see it in full operation and

From left: Capt. Mike O’Byrne, Hung, Doug LeTourneau and Hiep - the team interpreter.

At the end of October, LeTourneau joined recon team ST Virginia. It didn’t take long for LeTourneau to ingratiate himself with the indigenous team members of ST Virginia. One night, while LeTourneau was recording a taped message to his parents on his portable cassette player, Lap – the young point man on ST Virginia -- came into his room and spoke into the recorder: “I want to tell you parents of Private LeTourneau, not to worry about him. We respect him and I’ll keep an eye out for him. And, don’t worry; if an enemy shoots at him, I’ll catch the bullets with my body. I’ll protect your son. Thank you for sending him to Vietnam. He’s a good soldier.”

In late November, on the third day in Laos, LeTourneau earned his unique spot in SOG history: as he rose from a sitting position he slung his rucksack on his back. Just as it hit his back, enemy AK-47s opened fire. LeTourneau was suddenly slammed to the ground face first.

The impact was so severe he thought he had broken his nose. The NVA left him for dead. LeTourneau removed the rucksack to discover that four AK-47 rounds had ripped through it and the PRC-25 FM radio inside of it. Shortly the NVA launched several attacks against ST Virginia. NVA soldiers advanced toward LeTourneau and ST Virginia team member nicknamed Cowboy. As they moved toward an LZ they fired their weapons. Without saying a word, the two men took turns firing at the enemy while moving down hill. Rotating around each other. Cowboy and LeTourneau would fire several bursts from their CAR-15s, and then reload.

ST Virginia was finally extracted from the target by South Vietnamese-piloted H-34 choppers, codenamed Kingbees. The entire team was lifted out of the jungle on ropes from the helicopter, where team members were peppered with shrapnel from enemy rocket fire. A few weeks after that mission, fellow recon men marveled as medics pulled out pieces of shrapnel from his arms, neck, head which had become infected. This was the first of 13 SOG recon missions and one Bright Light mission that LeTourneau would run during his one-year tour of duty in Vietnam.

The last mission LeTourneau ran with RT Idaho, to recover two downed Air Force pilots. On that day in early October, a powerful HH-3 chopper took the team straight in to the LZ. LeTourneau was the first one out of the chopper. As he jumped, the chopper lurched upward momentarily and descended back to ground, with the right wheel landing on LeTourneau’s chest. “I was lying there and couldn’t move. I was afraid I was going to die right there,” he said.

Team Leader Lynne M. Black Jr. and Le Tourneau set about the grisly task of trying to extricate two dead Air Force pilots from an O-2 observation plane that crashed into a berm that was covered with elephant grass. NVA soldiers swarmed in and around the crash site firing rounds at RT Idaho. Black recounted in admiration how calm Le Tourneau was under fire, and how he took charge of setting up team defensive positions before trying to extract the bodies from the twisted wreckage of the crushed Cessna. It was apparent to Black the pilots were dead and that it was impossible to free the bodies of the pilots. The bodies were so tightly wedged into the small aircraft’s mangled fuselage that it would take cutting torches and crowbars to get them out.

They were ordered to recover any items from the plane that had intelligence value and prepare for an immediate extraction. LeTourneau added: “During all of this, I looked across to Lynne and said, ‘I don’t think we’re going to make it out of here. They (the NVA) are closing in on us, the weather is clouding over….’ Lynne looked back at me and agreed. I’ll never forget that moment. We didn’t think we’d get outta there alive. I took the pilot’s watch, it stopped at 10:10 a.m., the moment they crashed, so his family would have it.”

As Black recovered maps, secret documents, codes, and personal information from the pilots, LeTourneau called in a series of deadly airstrikes on the NVA. Finally, it was time for extraction, the Jolly Green Giant couldn’t land, but dropped ropes down for extraction. “Every mission I ran, we were pulled out on strings, this one was no different,” LeTourneau said.

An A-1 Skyraider punctuated that mission with a special display of flying verve and skill: As RT Idaho was being lifted out of the jungle on ropes, an A-1 flew underneath the team, bringing in an airstrike on the downed aircraft and enemy soldiers. “I’ll never forget it, he flew underneath us, I could see inside his canopy. Damn, that was close.” Once the team was out, airstrikes destroyed the aircraft and kept the NVA from getting their hands on the bodies of the airmen. No member of RT Idaho was injured. A couple of days later, LeTourneau returned to “the world”, his last memory of a SOG mission being of a honorable but ultimately futile effort to reclaim the bodies of some of America’s finest airmen.

Green Berets who served with Doug LeTourneau during the secret war, and his son LJ LeTourneau render a final salute on August 7, at LeTourneau’s grave site in the Pierce Bros. Valley Oaks Cemetery in Westlake Village, CA.

He went on to become a master carpenter, builder, eventually building everything from stylized log cabins to massive Wal-Marts, a bank and hundreds of homes in northern California. LeTourneau also earned his fixedwing and rotor pilots licenses, while returning to his first love from his FFA days, showing his prized Hereford cattle around the country.

However, like many Green Beret combat veterans, the thing that he was most proud of, after his loving family, was his service in the secret war under the aegis of the Military Assistance Command Vietnam – Studies and Observations Group, or simply SOG, for that one-year tour of duty with RT Virginia and then with RT Idaho at FOB 1 and CCN. Because it was a secret war he couldn’t talk about it with his family for years, but he was proud to finally share those stories, especially with him his father, a B-17 pilot during WW II who flew 13 missions over Europe before being shot down on April 13, 1944 and serving the remaining 13 months of WW II in a German POW camp. He attended a Chapter 78 July 13 meeting where he shared some of those stories and of his growing up in Southern California, attending Van Nuys High School, where another alumnus, Chapter member MG (Ret.) John K. Singlaub attended before WW-II. During that meeting he spoke of his friendship with fellow recon man Eldon Bargewell.

We all met at FOB 1 in 1968, we all ran recon. And Eldon survived getting shot in the chest by an NVA soldier in Laos, which LeTourneau notes: “Eldon and I always joked about how we both got shot by the NVA with AK-47s and lived to talk about it. It was an unique, little club.”

Lynne M. Black Jr., who served in SOG for two years including running 10 missions with LeTourneau, said this: “Doug was the most professional One-One I operated with during my two years in SOG.”

For more LeTourneau exploits, read Meyer’s accounts of the secret war in “Across The Fence, The Secret War in Vietnam – Expanded Edition,” and “On The Ground, The Secret War in Vietnam.” “Across The Fence” is also available as an audiobook with Audible.

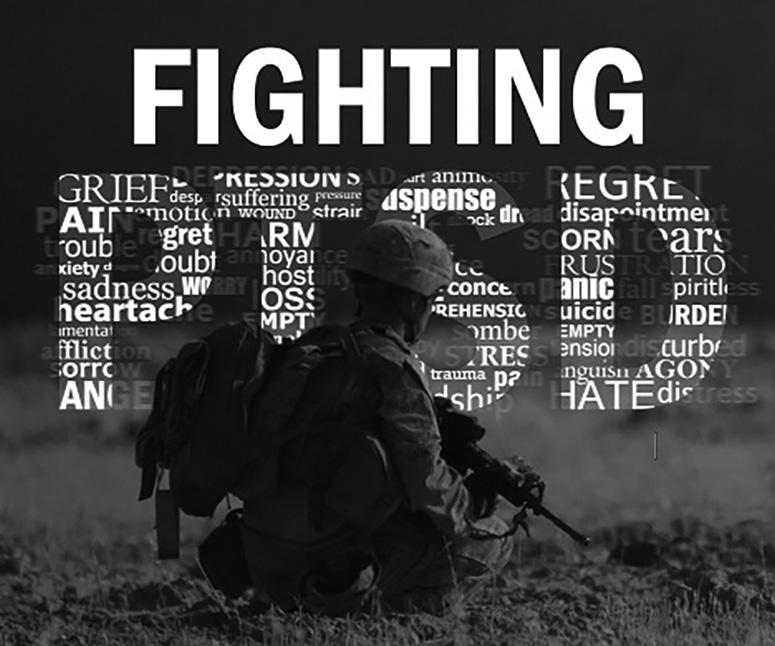

WOUNDS WE CANNOT SEE

Post Traumatic Stress Disorder does not always allow the affected to seek help. Lend a hand and provide them with methods of help, listen and be a friend.

San Diego Veterans Magazine works with nonprofit veteran organizations that help more than one million veterans in lifechanging ways each year.

Resources.

Support.

Inspiration.

At San Diego Veterans Magazine you can visit our website for all current and past articles relating to PTSD, symptoms, resources and real stories of inspiration.