5 minute read

CLIMBING AND CONSULTATIONS IN THE RED CENTRE

WORDS BY HETTY DE CRESPIGNY

WHEN HETTY MOVED TO MPARNTWE, SHE WANTED TO KEEP CLIMBING, BUT WITHOUT CLEAR PERMISSION FROM TRADITIONAL OWNERS, OR RECORDS OF PAST CONVERSATIONS, SHE WAS UNSURE HOW TO PROCEED. SO SHE ESTABLISHED THE FIRST FORMAL GROUP TO BEGIN A GENUINE CONSULTATION PROCESS.

Advertisement

When you arrive by plane in Mparntwe/Alice Springs, the first sign you read at the airport is in Central Arrernte: Werte (welcome). From the moment you set foot in this town, it’s very clear that this is a place where language, culture and connection to Country run deep.

Central Australia suffered fewer blows from settler Australia than areas on the east coast. Walking through Todd Mall you’ll hear in excess of seven different Aboriginal languages spoken by people who hold unbroken ties to their ancestral lands, much of which they hold either native title or freehold title over, recognised under the Aboriginal Land Rights Act.

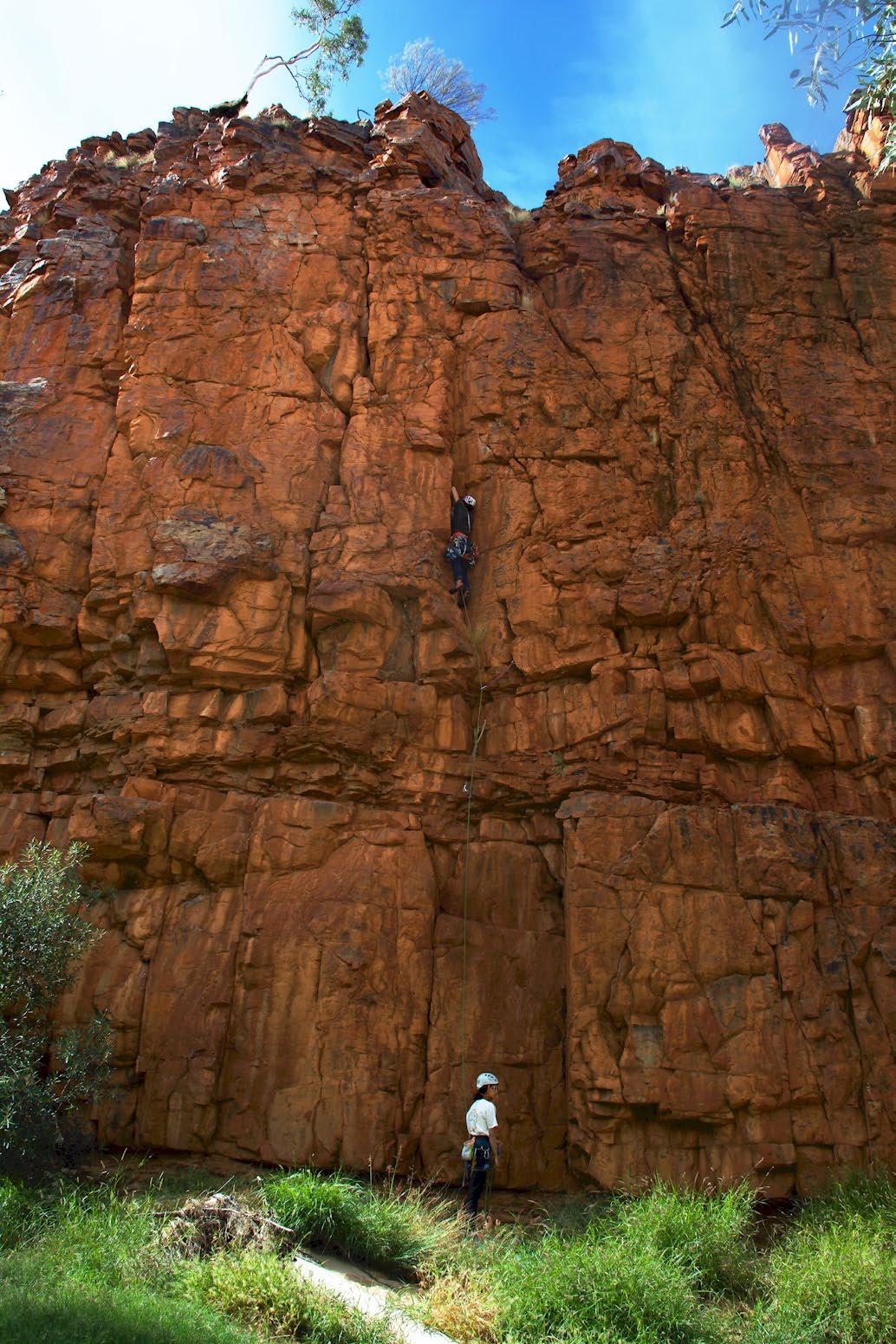

Climbing here, you are keenly aware that you are climbing on someone else’s land, where people hold an unceded, continual connection to the rocks, sand, earth and waterways for the past 50,000 years. Dreaming tracks and sacred sites permeate the landscape with ancient names that are held and recorded, indisputable proof that this always was and always will be, Aboriginal land.

Crimson ruby cracks, dusty orange ledges and salmon pink sunsets; I never knew there were so many different shades of red until I climbed in Central Australia. Over the last few years I’ve been fortunate to call Mparntwe home. I have experienced the joys of climbing in 40 degree heat, only minutes from home amongst ghost gums, red sand and quartzite seams overlooking vast desert plains.

Access to climbing anywhere is laden with complexity, but here I felt a stronger urge to clarify what places had been properly discussed with traditional owners, before racking up and putting rubber on the crag. I met several climbers in town within my first few months, some of whom had climbed prolifically around the area, and others, who despite being passionate climbers, refused to get on the rock for fear that they would be offending the rights of traditional owners.

Many of the climbers I met in Central Australia work closely with Aboriginal people in the region, so respect and strong relationships were common amongst climbers and traditional owners. Despite this, it became apparent to me after reaching out to climbing folk, that there was no access group, no clear record of adequate consultations and resulting permission to climb at any of the places listed on thecrag.com.

And people were certainly still climbing at these places, often relying on third-hand information. I’d hear that “[so and so] spoke to a traditional owner who they worked with about climbing at [insert location] and they said they were fine with it.”

But the details were always hard to confirm. Something didn’t feel right. I couldn’t help but think that climbing in potentially sacred areas as a non-Aboriginal person was an act of neo-colonialism.

In the Northern Territory, there are large bodies like the Central Land Council (CLC) whose primary remit is to consult traditional owners on land use, in line with their traditional decision-making structures. The Northern Territory is the only jurisdiction in Australia where there is legislative provision for the return of inalienable freehold title to Aboriginal owners.

The more I learnt about land tenure around Mparntwe, the more I feared that we were climbing without proper permission. The CLC

By Irvin Bubar.

had clear processes for facilitating consultations for other land users on both Aboriginal Land and land with a Native Title determination. It was in stark contrast to taking a third-hand reassurance as permission to climb.

The idea to really do something about it came from my friend Grace after an early morning climb at a crag located on a nearby cattle station, named Flintstones (the only place we felt vaguely okay climbing at). “Het, why don’t you just set up a meeting with all the climbers in town and start an access club? Open the conversation formally.”

It seemed like a huge task to take on, but the decision was obvious. In August 2021, the first meeting took place in the backyard of my sharehouse, and Rockclimbers of Central Australia (RoCA) was born.

I was filled with excitement and energy after 18 climbers around the table all agreed that it was time we clarified access to climbing sites in Central Australia. We all knew that there was a real chance that consulting properly with traditional owners over the half-dozen good climbing spots could result in a resounding “no” to further climbing.

The most heartening takeaway from the meeting was the unanimous understanding that proper consultation meant being committed to accepting and respecting whatever decision we were given.

Over the next two years, with the support of locals who had climbed in the area for years, RoCA began consulting with the NT Parks and

Wildlife Service, who are the managers of most of the land where climbing occurs in Central Australia. Most of the parks around Mparntwe are jointly managed by NT Parks and traditional owners, and major decisions are made through a joint management committee, made up of representatives from traditional owner families for the land in question. We provided GPS locations of the major sites and requested that these be discussed at joint management meetings with traditional owners.

One site we focused on was Boggy Hole, located in the Finke Gorge National Park (see Pete Wyllie’s VL article in Issue 36 for detail). RoCA arranged for videos and photos of trad climbing techniques to be shown to traditional owners at the Finke Gorge joint management meeting. This would help ensure that if consent was obtained, people properly understood the activity that was proposed—no bolting, no trace, trad climbing only.

The traditional owners at the meeting were interested in the activity and wanted to support people to enjoy their hobbies in the national park, sharing their love of a beautiful place. They requested that they have more time to make their decision; there were Elders who would need to be part of the decision that were not present at the meeting. Proper consultation takes time, but the foundations on which RoCA was formed were clear: we would ask the question and follow the proper process.

Other sites of focus included the Ormiston Bluff crag in Tjoritja National Park and the crags to the west of Emily Gap in Yeperenye Nature Park. After consulting with Parks, we confirmed that traditional owners had previously indicated they were supportive of people climbing here. A phone call to the ranger was recommended, and we were reminded that no new bolting was permitted.

A very happy trip followed with several members of the club enjoying a delightful climb mid-May at Ormiston Bluff in 2022. This time of year the weather is truly a climber’s dream, with mornings cold enough that your hands don’t sweat but aren’t numb, the sun warming the rock by the middle of the day just in time for a lazy picnic in the middle of a dry sandy river bed. There are lots of good intro-level trad routes, with a classic 20m crack climb, Wham Bam Thankyou Jam (18), for the bold. Not a cloud in the sky, climbing in t-shirts in the early arvo sun, it felt like progress.

This truly is a special place to live and work on, and to have the blessing of people whose connections run deep through the land left us with a feeling of gratitude as we sat by the campfire that night reflecting on the day’s adventures.

For updates on access in central Australia check out rockclimbersofcentralaustralia.org