8 minute read

test of strength

Some of life’s most important lessons are learned outside the classroom

By Rachel Stone

High school graduation is a milestone .

Some acquire their diploma easily. Others earn theirs against all odds. These graduating seniors didn’t let life’s blows keep them down. This month, they will cross the commencement stage knowing their tribulations made them stronger.

“Dr. Miranda is an amazing dentist. Every time I talk with him I learn more about the latest techniques in dentistry. His experience, skill and passion for dentistry come through crystal clear. Complex cosmetic, implant and restorative dentistry requires a doctor like Dr. Miranda. I can recommend Dr. Miranda without reservation to anyone that wants world class dentistry.”

- Dr. Scott Rice, DDS Irvine, CA

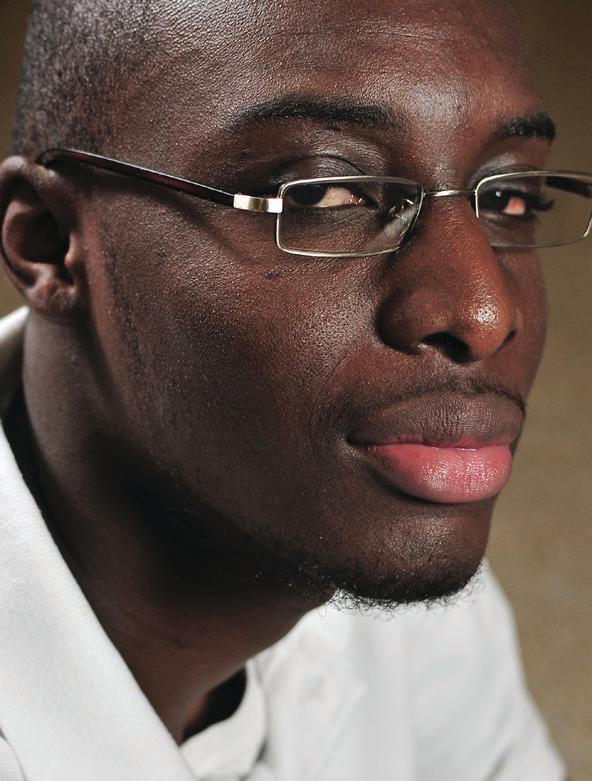

DEMA SANE WAS EXCITED ABOUT HIS NEW HOME.

It was fall 2009, and the 17-year-old Senegal native landed in New York with plans to finish high school there.

His dad is a consultant who travels throughout the world, and his mom was living in New York at the time.

But soon after he arrived, he was in the hospital with malaria.

“I don’t know how that happened,” he says. “It’s fairly common in Senegal, but it’s unheard of in New York.”

He was in the hospital for a week, and it took months before he could climb a flight of stairs without utter exhaustion. Sane decided the Big Apple wasn’t for him. So he moved to Dallas, where he found a home with Alene Mathis, a Woodrow counselor whose church has a connection to Sane’s church in Senegal.

Now a 19-year-old senior, he says he has the highest grade-point average of anyone in his class (he’s not in the running for valedictorian because students with Advanced Placement credits outrank him). His favorite subjects are astronomy and global business.

“I’ve always wanted to be in the U.S.A.,” he says. “I have a love for English.”

Making friends wasn’t that hard, since people in Texas are friendly, Sane says.

But adjusting to the culture has been difficult.

Kids are flashier here than in Senegal. They have strange haircuts. And school is different — more lax in some ways, stricter in others.

The worst part is the weather.

“In Senegal, there was a beach, and we used to go to the beach all the time,” he says. “I thought I would have no problem with the weather, but surprisingly, it was hot. It was really hot here.”

Mathis says Sane often gets homesick, although he doesn’t show it. He talks on the phone to his mom a lot.

“I don’t know if I could do it,” she says. “Especially not at that age. He’s so far away from anything familiar to him.”

Malaria is an illness that never quite goes away completely. But Sane is healthy enough that he played on the varsity basketball team, which went to the playoffs this year.

Sane doesn’t know where he’s going to college, but he has talked with George Washington University, the University of North Texas, the University of Texas at Arlington and others about attending on a basketball scholarship.

Even though he was alone in Dallas, he found friendship and family in Woodrow.

“Playing sports helps because you make new friends, and they become like brothers to you,” he says.

972-733-5266

The 18-year-old Bishop Lynch senior and her 16-year-old sister were on the way to NorthPark to have their makeup done for homecoming on Oct. 2, 2010, when someone ran a stop sign and slammed into their passenger side door.

“I thought I was perfectly fine,” she says.

They went home, changed into their dresses and went to the dance.

“The next day, I didn’t wake up at all,” Isaac says. “Everyone was trying to wake me up, and I was completely gone.”

At the hospital, she was diagnosed with a severe concussion and sent home.

“It got worse to where I couldn’t walk. I couldn’t talk. Everything was really jumbled,” she says.

A neurologist diagnosed her with severe concussion and trauma-induced migraines in the midbrain. Over the following months, she would endure severe treatments she describes as “like chemo for your brain”, plus physical and speech therapy.

But most frustrating was learning differences she incurred.

“I would try to write things down, and it would come out as scribble scrabble,” she says.

When most of her college applications were due, Isaac was in the hospital, relearning to write and pronounce words.

“That was hard because I really couldn’t even think for myself, so my mom really had to help me,” she says.

Bishop Lynch president Ed Leyden says Isaac never considered graduating later or taking time off. She couldn’t interview with colleges because of her injuries, but she was determined to get into the best schools possible, he says.

“She wanted to come back here and be active here,” he says. “It took a lot of willpower, especially in dark times when she didn’t feel good.”

Isaac’s body and brain are healing, but she still struggles with learning differences. She has trouble with auditory processing, which means she can’t take effective notes in class. And she struggles with reading comprehension. It’s frustrating, but she says she is learning to work around her differences.

“At first I was sad, and then I was mad,” she says. “And then I realized it was OK because everyone has something to overcome.”

Recently, Isaac found out she was accepted to the University of Oklahoma, one of her top choices. She wants to study biochemistry and become a pediatric oncologist.

“You can’t take anything for granted because you never know when things are going to change,” she says. “I really appreciate my family more and being healthy. It’s made me a much stronger person.”

He did enough to get by, but he didn’t push himself.

That all changed June 24, 2009.

That night, his mom was at a conference in San Antonio. His dad, a cab driver, was working. Ikemenogo went to bed about 1 a.m., and he awoke to the phone ringing at 4 a.m.

“It was my mom telling me my dad was shot,” he says. “I thought it was a dream at first, and I started laughing like it was a joke, and then I felt sick because I realized it was real.”

Two carjackers had shot him in the lung, and he was in critical condition at Parkland.

5017Radbrook....................$1,295,000

Ben Jones/Chris Pyle

6222 Rex.............................$1,279,000

Ben Jones/Chris Pyle

5603 Dittmar.......................$1,099,000

Ashley Rupp 5036 Airline.........................$1,095,000

Sharon Palmer

4569 Belfort...........................$955,000

Shirley Cohn

4554 Westway........................$899,000

Shirley Cohn

4140 Fawnhollow...................$499,000

Ryan Hill 2830 State..............................$459,000

Ben Jones/Chris Pyle

3827 S. Versailles....................$390,000

Shirley Cohn

3921 Wycliff...........................$345,000

Forrest Gregg

2320 Throckmorton................$280,000

Ashley Beane

4223 Buena Vista #12.............$275,000

Ryan Hill/Ashley Beane

6428 Axton.............................$269,000

John Eller

6659 Aintree...........................$229,900

Blake Eltis

4242 Lomo Alto #N47............$210,000

Ashley Rupp

3400 Welborn #105................$189,900

Blake Eltis

4104 N. Hall #334..................$164,900

Ben Jones/Chris Pyle

5319 Manett...........................$132,900

Ben Jones/Chris

At the time, Ikemenogo and his younger brother, both students at Bishop Lynch, were enrolled in summer school. The first day, they contacted the school to notify them they would be absent.

Ikemenogo considered dropping out of summer school classes.

“My dad couldn’t talk because he was in ICU,” he says. “And my mom couldn’t talk because she was crying all the time.”

He tried to think what his father, an immigrant from Nigeria, would say if he could ask him what to do.

“My dad puts education above everything,” Ikemenogo says.

So he and his brother went to school the next day. It was hard, he says. They couldn’t concentrate. They were sad and afraid. But they were there, and eventually, they completed their classes.

Evelyn Grubbs, the Bishop Lynch math teacher who was overseeing summer school that year, says Ikemenogo sets very high standards for himself.

“Of course, he was very upset when his dad was shot, but one thing of grave concern to him was that he didn’t have a ride to school,” Grubbs says. “We kind of banded together, and several of the teachers here picked him up for school, and then his uncle started bringing him. But he didn’t miss. He was not going to miss.”

It was “the worst summer ever,” Ikemenogo says. His dad couldn’t work, and without work, there was no income.

The air conditioner broke in July, and they didn’t have money to fix it. They didn’t have money to pay the water bill, and soon, their water was turned off.

Neighbors and friends pitched in to help the family, Ikemenogo says. But the ordeal gave him an epiphany.

Education is the most important thing. It’s the only way to have stability, a secure career, money in the bank.

“I realized I have to work as hard as I can because it’s hard to come up with money,” he says. “You can’t take things for granted.”

His dad pulled through, and he still drives a cab for a living. He walks with a bit of a limp in his step, Ikemenogo says, and he doesn’t like to talk about what happened.

Now Ikemenogo makes all A’s and B’s. He has been accepted to 12 schools, including Syracuse and Virginia Tech, although he hasn’t chosen a school yet.

He wants to study architecture or business.

We’re inviting our neighbors to shop, eat, and drink locally. So, join us at Lakewood Village Shopping Center (Gaston & Abrams) and enjoy live music, local food, and area artists from Noon to 8 p.m. There will be kid’s activities and many fun surprises. Admission is free, so come explore your neighborhood with us.

At only 17

EDITH RODRIGUEZ knows exactly what she wants to do in life.

She wants to become a lawyer who helps abused women and children. It’s personal for her.

When Rodriguez was 13 and living in her hometown of Zacatecas, Mexico, she fled to Texas with her mom, sister and brother.

“My father was always on drugs, and he was always abusing my mom, physically and verbally,” she says. “We were always hiding from him because he was so crazy.”

He set fire to their house, she says, and when it didn’t burn to the ground, he sold it so they would have nowhere to live. That’s when they came to Texas; they have temporary work visas, and they expect to gain permanent residency status in about two years.

Rodriguez’s mom worked and enrolled the kids in school at Woodrow Wilson High School and J.L. Long Middle School. They settled into life in our neighborhood.

It wasn’t easy for Rodriguez and her 11-year-old brother. Neither of them spoke any English. Rodriguez was told she would need an extra year of school, and at J.L. Long, she was put in the lowest-level classes. But in about a year, she could speak English fluently, for which she credits the ESL teachers at Long.

She takes extra classes through a computer-assisted learning program at Woodrow. She makes all A’s and B’s, and she graduates this month, on time.

Case Wallace, who teaches the computer-assisted learning program at Woodrow, says Rodriguez could have taken her time, especially considering she had to learn one of the world’s most difficult languages. But she put in overtime to graduate in four years.

Still, a cloud hangs over her.

A few years ago, her dad found them.

“My father was in New Orleans, and he tried to come here and get back with my mom, but my sisters and I told her to stay away from him,” she says.

He didn’t take rejection well.

One day, when Rodriguez’s mom was at work in an East Dallas taquería, her husband came in and stabbed her. He was trying to kill her, Rodriguez says, but her mom escaped serious injury. The father, who is a U.S. citizen, went to jail for aggravated assault.

Rodriguez works Saturday and Sunday at La Madeleine. And her mom has opened her own taco stand in Pleasant Grove. Rodriguez plans to take basic courses at community college, transfer to SMU and then go to law school.

Her dad gets out of jail in about a year.

Ask her if she’s worried about that, and she pauses. She throws her eyes to one corner of the room, and quietly, she says, “Only a little bit.”

She’s not sure what she’ll do once he’s out, but she knows she wants to stay in the United States.

“I wanted to come to school to get a better future so I can help other people,” she says.

Owner Ron Hall is a Texas Master Certified Nursery Professional, Licensed Irrigator, Certified Landscape Professional, an Arborist, and an Award Winning Landscaper recognized through Texas Nursery