3 minute read

Freedman ’s Town 1870s-1900s Tenth Street Historic District

Robert Swann grows emotional when he talks about his 122-year-old house, its story and the neighborhood into whose fabric it is woven.

A highly skilled carpenter named Richard J. Moore, the son of freed slaves, built the 720-square-foot house in what is now the Tenth Street Historic District, in 1896.

Swann jumped through hoops for most of a decade to buy the abandoned house from the city of Dallas in 2016. If he hadn’t, the city likely would’ve demolished it.

This neighborhood just east of Interstate 35 and south of Eighth Street is part of the original Oak Cliff and was known as “Miller’s Four Acres.” The former slaves of cotton plantation owner William Brown Miller began settling there shortly after the end of the Civil War.

Freedmen who migrated from Alabama, the Boswell family, began buying lots and building homes there in 1888. The neighborhood had a school, two churches and small businesses among the 300 or so houses.

In some places, such as Winnetka Heights, “historic district” means that buildings cannot be torn down. At the very least, tearing down a house in a historic district ought to be very, very difficult.

Not so in Tenth Street, one of the nation’s few remaining freedmen’s towns.

A passage in the city of Dallas development code states that homes in historic districts can be demolished by court order if they comprise less than 3,000 square feet and are a “nuisance.”

The city approves demolitions in the neighborhood with ease, Swann says. Because of that statute, little can be done to stop or even delay the destruction.

“It’s de facto discrimination because we don’t have any structures in Tenth Street that exceed 3,000 square foot,” says Swann, who serves on the city’s Landmark Commission. “What’s really upsetting is that these houses are rushed through demolition before they’re even offered at tax sale.”

Many Tenth Street houses were handed down through generations. Let’s say your aunt dies at age 90, and no relative claims her house. Someone boards it up, and it’s forgotten. There’s no clear heir, and the house falls into title limbo.

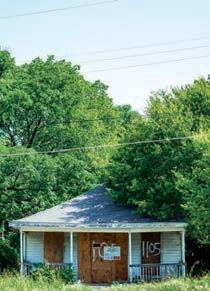

Consider 1105 E. Ninth St.

The Landmark Commission gave the house at that address a 30-day reprieve from demolition on July 2, after a court order was granted.

This park-facing cottage three miles from Downtown is 107 years old and has been vacant for about 12 years. It has a cloudy

LEFT: A Tenth Street Historic District house that the city is moving to demolish. BELOW: Most of the homes in Tenth Street comprise less than 1,000 square feet, but there are a few exceptions. BOTTOM: The Elizabeth title, but the city could foreclose on it for delinquent taxes, sell it at auction and hopefully get it back on the Dallas County tax rolls.

Instead, they’re moving to demolish it.

Tearing down the house does nothing to clear up the title, Swann says, and it decreases the property’s taxable value by half.

Besides that, the city has to foot the bill for demolition and maintenance of the vacant lot.

The Ninth Street house is a perfect example of the neighborhood’s history, Swann says.

It was built in 1911 by William Smith, the son of freed slaves, and it stayed in Smith’s family until 2005, when the resident died.

“It has stood for 107 years, and it’s been vacant for at least 12 years, and now we’re talking about being able to remove the nuisance ‘in a timely manner,’ ” he says.

Some longtime neighborhood residents would like to see the neighborhood become a livinghistory museum akin to Colonial Williamsburg.

In American history, we talk about slavery, and we talk about the civil rights era.

“The beauty of Tenth Street is that it tells the most under-told story of the African- American experience, and that’s Jim Crow,” Swann says.

Tenth Street will be affected when a deck park is built over Interstate 35. Whether it damages the neighborhood or lifts it up will be a test for the city of Dallas.

Tenth Street neighbors envision the Dallas Zoo, the deck park and their historic freedmen’s town living together as a greater cultural campus.

In the meantime, Swann wants to find a way to exempt Tenth Street and Wheatley Place, a historic African-American neighborhood in South Dallas, from the 3,000-square-foot rule.

The 720-square-foot castle that he’s restoring stands as a tribute to the triumphs of the people who lived there.

“A lot of people see these houses and they see poverty,” Swann says. “No, that’s building wealth.”