3 minute read

trash to treasure

How it works: bioreactor technology

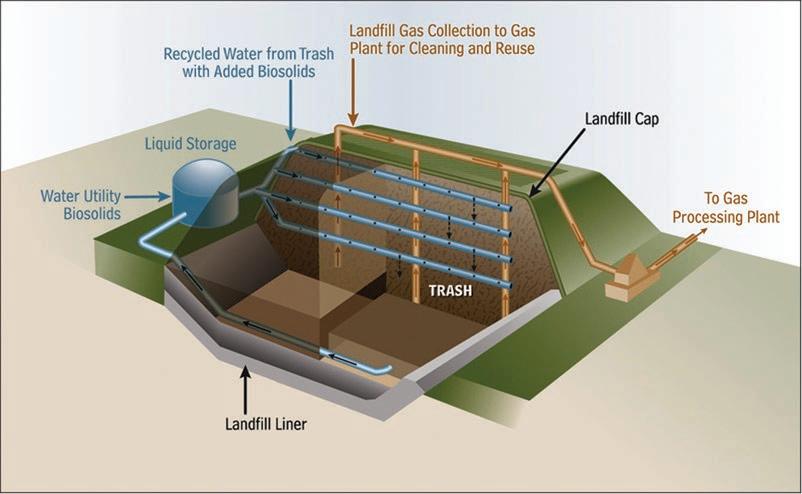

• On the east end of the dump stands a tower that stores sludgy recycled trash water containing bacteria, fungi, and other microorganisms or microbes.

• The yucky mix flows from the storage tower into horizontal perforated pipes that line the landfill.

• The liquid is then injected into the trash, where it acts as food for hungry microbes, causing the trash to decompose much faster than it normally would.

• Accelerated decomposition means faster generation of valuable gaseous byproducts — methane and carbon dioxide.

• Another set of vertical pipes act like wells, sucking up the gas and transferring it to a processing facility on the west end of the land.

• Machinery at the processing site sterilizes and separates the gases, preparing them for sale to Atmos Energy and other customers.

cated to dealing with the city’s waste (accepting about 2 million tons of trash per year, the Mc c ommas b luff is t exas’ biggest dump).

On the east end of the dump stands a tower that stores sludgy recycled trash water containing bacteria, fungi, and other microorganisms or microbes.

t he yucky mix flows from the storage tower into horizontal perforated pipes that line the landfill.

t he liquid is then injected into the trash, where it acts as food for hungry microbes, causing the trash to decompose much faster than it would normally.

Accelerated decomposition means faster generation of valuable gaseous byproducts — methane and carbon dioxide.

Another set of vertical pipes acts like wells, sucking up the gas and transferring it to a processing facility on the west end of the land.

Machinery at the processing site sterilizes and separates the gases, preparing them for sale to Atmos e nergy and other customers.

T He Economy Of Space

Garbage service is built-in for the city’s single-family homes (it accounts for the biggest chunk of the $20.98 charge on our monthly sewer bill), but multi-family complexes or businesses have to pay by the ton to dump trash at the landfill. b ecause Mc c ommas b luff is so large, Dallas accepts trash from other counties, commercial outfits and anyone else willing to pay its $21-per-ton fee. t hat’s the most substantial way the city generates revenue on Mc c ommas b luff, a total of $25 million in 2008. t he city expected to net $28 million in 2009, but a good portion of its customer base is the construction industry, and because the economy has weakened, Nix says, construction tapered off so the city expects to net $23 million. t he landfill opened in 1981 and is projected to be used until 2031, when it originally was estimated to fill up. b ut bioreactor technology could mean it will last much longer than that — another 22 years, Smith says. b ecause the technology breaks down garbage more quickly, it means the amount of garbage in each cell will decrease more quickly, translating into more space in the landfill and Smith says, space equals money. t he cost to run the landfill was $18.5 million in 2008, so with dumping fees plus residential garbage fees (roughly $4 million annually) the city expects to earn roughly $9 million in 2009.

And if, as Smith predicts, new technology evolves that changes landfills from finite to infinite space, Mccommas bluff could continue operating as a city cash cow for decades and even centuries to come.

Reduce, R euse...

you know the R est r ecycling has come a long way in Dallas, Nix says. “We were pretty behind for a long time. We did not follow the green track in late ’80s and early ’90s,” she says.

In 2005, only about one in four Dallas households recycled. t oday, Nix says almost half of Dallas homeowners recycle: “Our count of recyclers, as provided by route drivers and further estimated based on big blue cart deliveries, is 46 percent.” t he city’s goal for the “ t oo Good t o t hrow Away” program, which educates homeowners on recycling and provides the blue bins for single-family residences, was 50 percent of eligible households by 2011.

“We ought to get there a bit earlier than estimated,” Nix says. “We’re certainly seeing big strides in the amount of recycling materials we’re collecting.” e ffective recycling programs mean more landfill space; our current recycling rate means we save more than a month of landfill space every year.

“When we bury something, we hope it will degrade,” Smith says. “ e verything we want to go into the landfill is not this type of stuff [gesturing toward a plastic water bottle from which he’s drinking]. We want it to decompose.” t he city doesn’t sift through garbage to mine recyclables, so any non-biodegradable items tossed in the trash remain in the landfill taking up space.

“We would love for it to be out,” Smith says. “It’s not a perfect world but it is getting better.”

25,000

Number of homes that can be heated daily by the landfill’s methane emission

30

Percentage of time by which the landfill’s life expectancy should increase because of bioreactor technology

20

Number of landfills in the nation using bioreactor technology (Dallas was the first landfill in t exas to try it)

308

Number of methane wells reaching down into the Dallas landfill

120

Feet each well extends into the landfill waste (the waste is at least 130 feet deep any place a well exists)

$100,000

Average net amount the city makes each month from the sale of methane

250,000

Gallons of liquid that can be pumped into a cell each day to jump-start the microbes in bioreactor technology

60,000+