8 minute read

Somewhere down the Chocolate River

For decades, New Brunswick’s Petitcodiac River didn’t get the respect it deserved. That’s changing and it’s about time

BY ALEC BRUCE

It was half past 4 o’clock in the afternoon and the biting flies were out for a snack at the headwaters of the Petitcodiac River. Downstream, where the river crashes into the highest tides in the world, it turns into something resembling 25 square kilometers of chocolate milk shake. But up here—long before it meanders past southeastern New Brunswick’s alluvial plains, towns and farms—it was as smooth and clear as glass. And buggy.

“They’ve been getting worse recently,” said my guide (whom I’ll call Jim), snatching mosquitos out of the air by the handful. “For generations, the gypsum caves along the river made perfect homes for little brown bats. You know one of those critters can eat 1,000 insects in an hour? Anyway, they’re gone now, thanks to white nose fungus or, maybe, climate change.”

Jim is a wildlife specialist who works for one of the local First Nations. Their ancestors inhabited these shores for thousands of years before European settlers arrived. He’s a Scots-Irish gent, 40, fit, and full of topical knowledge. “We used to have a lot of fish in the river, too,” he said. “Everything you can imagine: salmon, gaspereau, brook trout, bass, perch, sturgeon.”

The problem, he said, is man. The problem, he said, is always man. “The good news is man can always make things better.” He looked up from his clipboard. “We’re making things better right now, right here.”

I hadn’t been back on the river in years. Travel, work, a move to Halifax—life—had reordered my priorities. But I’d recently snatched an opportunity to return, to see how my beloved “Chocolate River” had come along since I’d been gone, since the city of Moncton and the provincial government finally reversed years of neglect and began to restore its riparian health for eco-tourists and river rats like me. And so here I was, talking about the future—while also getting eaten alive.

In the old days, I wouldn’t have needed a guide for an adventure like this. For more than two decades, I was fond of gambolling along the Petitcodiac’s banks alone and in all conditions. Whenever I wanted a break from writing my daily column for the Moncton Times & Transcript, I scooted down to Bore Park to watch the sandpipers pluck shrimp from the mud flats that stretched for miles. The river’s sameness—particularly where it bends to the south and widens on its last leg to the Bay of Fundy—was a steady comfort to me.

On the other hand, she wasn’t the prettiest watercourse I’d ever seen. New Brunswick’s Saint John River was larger and, in many places, lovelier. The Fraser, Thompson and Kootenay out west were far more conspicuous. Even the humble Saint Mary’s in Guysborough County, NS—where American slugger Babe Ruth once happily dropped a line, or several, for mighty Atlantic salmon—had more star power.

The Petitcodiac, by contrast, was a 79-kilometre-long brown ribbon that looked a lot like the muddy Mississippi, only

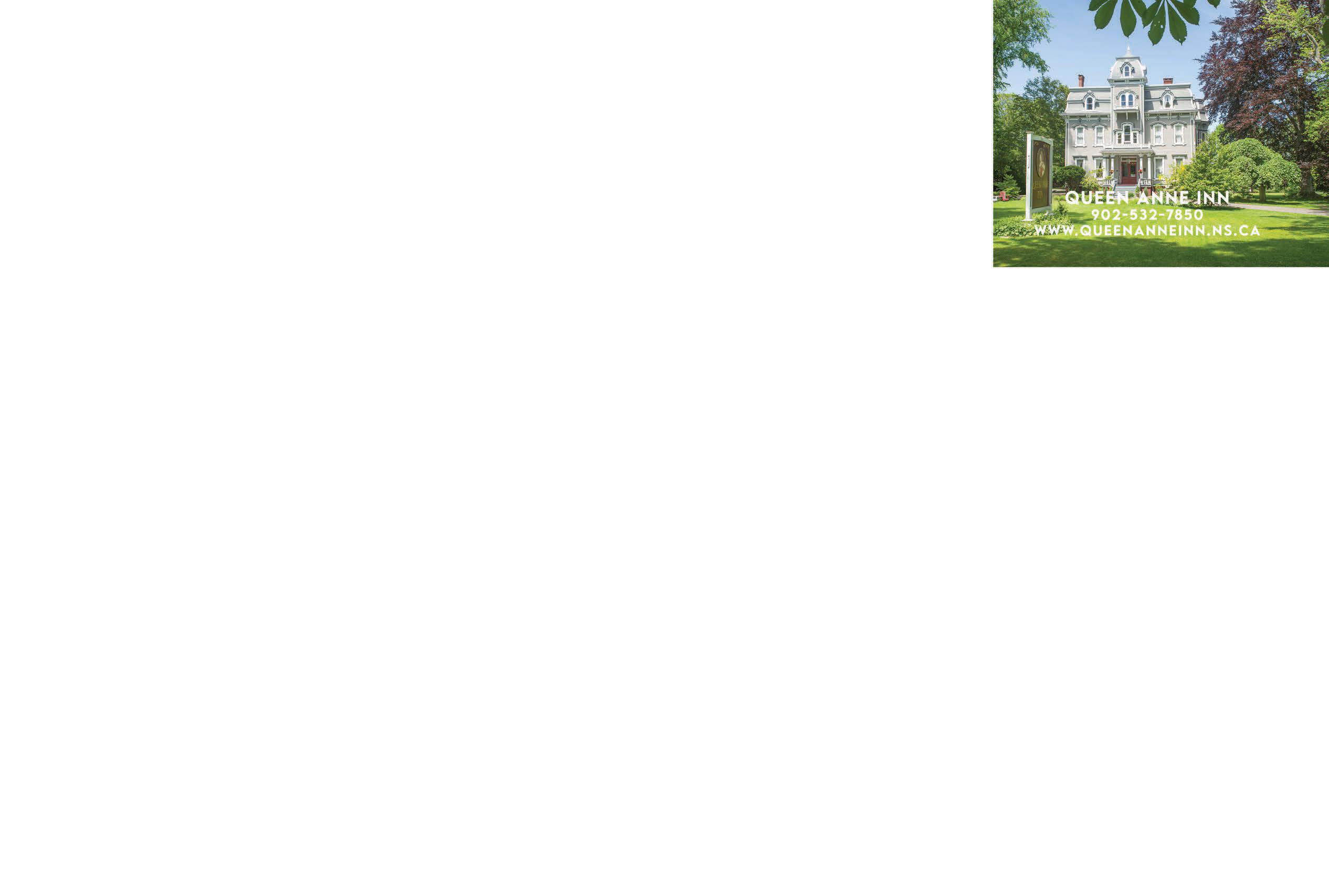

The tidal bore, the leading edge of the incoming tide from the Bay of Fundy, is popular with long board surfers and those content to watch the rushing—if muddy—water.

City of Moncton Tidal Bore

NEW BRUNSWICK TOURISM / DON RICKER

skinnier and shallower. Seeing it for the first time, American humourist Erma Bombeck allegedly quipped, “Hell…I retain more water than that.”

This may explain why, for decades, residents along its shores had taken it for granted. Certainly, no one gave it a second thought when Moncton officials decided to build a causeway in 1968. The fixed link made getting to work between the city and the town of Riverview on the other side easy enough. It also effectively destroyed the Petitcodiac, causing millions of cubic meters of silt to settle exactly where its fish normally passed—through special, but sometimes shuttered, gates—to spawn upstream. Still, they thought, it seemed a reasonable price to pay for progress. They were wrong, and eventually their civic successors knew it. We all did. I first noticed a shift in local attitudes towards the river in 2009, around the time I began writing on municipal-provincial relations. Moncton was riding high on a wave of entrepreneurial tech investment. It had begun to think of itself as a “smart city”, which no longer needed to scour its natural environment to bolster its bottom line. Climate change was on everybody’s lips and, suddenly, so was the Petitcodiac. Within five years, the turnabout was all but astonishing: The city permanently opened the gates; the river widened and deepened; the bore (the leading edge of the incoming tide that forms a travelling wall of water) recovered to its metre-high pre-causeway level. Long-board surfers from California may have been the happiest tourists to the area in 50 years. “It’s super cool, dude,” one told me in 2013.

Now, almost seven years later, I caught myself asking a version of the same question: “Is the river finally super cool?”

Jim’s about as tolerant and easy-going as a naturalist who spends his time fighting

PETITCODIAC RIVERKEEPER INC. (CC BY-SA 3.0)

Petitcodiac River Causeway

uphill battles can get. But he doesn’t much like the question. It presupposes that the Petitcodiac’s value is somehow cosmetic; its beauty only skin deep.

In fact, the river is—always has been—a crucial nursery for thousands of species of terrestrial and aquatic wildlife. It has formed the backbone of indigenous economies for countless generations. It’s only been since the so-called industrial age began that we seem to have forgotten this. Still, as he says, we are making things better “right now, right here”.

In February of 2021, the New Brunswick government’s department of transportation and infrastructure announced that it planned to start work on a new bridge to replace the causeway by October. Meanwhile, the city unveiled its scheme to add seven kilometres of new trails along the riverfront this year—anticipating, perhaps, that if they build it, people will come to admire what, until recently, got no respect at all. Perhaps, it is the dawning of the age of eco-friendliness, after all.

Perhaps, but on this late afternoon as the sun began to set behind the fir trees, there was still work to be done. “The fish certainly are coming back,” Jim said. “That’s great news. We just want to do everything we can to help them along.”

He jotted down a few more notes and talked about his employer’s work with the federal government and other partners in the public and private sector to restock the Petitcodiac with something nobody has seen in any quantity in years: Atlantic salmon.

“You know what salmon do?”

He grinned from ear to ear. He swatted another fly.

“They eat bugs.”

Your Home on Campobello Island

There’s No Time Like the Present to Discover the Past!

At Kings Landing, your senses will come alive with all things 19th-century New Brunswick. Don’t just imagine what life was like 200 years ago, step back and live it!

info@pollockcove.com • 506-752-2300