6 minute read

Big machines, big history

Nova Scotia’s Museum of Industry

BY DARCY RHYNO

BIGSTOCK / NEW AFRICA I t’s April 29, 1950, a breezy spring day in Stellarton on Nova Scotia’s north shore. You’re hanging the laundry on the clothesline with your four-year-old daughter. It’s a Saturday, so her three older brothers are off somewhere, hopefully not getting into too much mischief.

Suddenly, the thing that every woman and mother in this mining town most fears happens yet again: the earth rumbles beneath your feet. For a moment, everything—even the drying laundry flapping in the breeze—seems to stop. In the next moment, everything happens at once. You exhale the breath you didn’t know you were holding. Sirens wail. Women are screaming all over the neighbourhood. Children are crying. People are running toward the Allan shaft that descends into the Foord coal seam not five minutes from your back yard.

You abandon the laundry, sweep your daughter into your arms and join the rush because your husband, the father of your four children, the only family income is down there, an impossible 200 storeys underground.

When you reach the shaft, the draegermen have already assembled. You set your daughter down, keeping a tight grip on her hand, and catch your breath. There is hope. These men are trained to descend into the smoky, fiery hell that is an exploded coal mine with the singular purpose of bringing to the surface the miners who survived and the remains of those who didn’t.

You gather with the other women and children to watch, wait and pray. You don’t wait long. The first survivors surface in the cage of their own accord. They tell the crowd it’s completely dark down there. Men have to find their way to the shaft from more than a kilometre away where they’re working at the coalface. Fathers and sons are reunited with their weeping and much relieved wives, children and mothers.

The Albion

Within 45 minutes, 72 miners have surfaced, none the worse for their ordeal. That leaves seven unaccounted for—your husband is one of them. The draegermen descend. What seems like hours later, they surface with five of the seven, some of them injured. One says he led the others by feeling his way along the railway tracks.

As the draegermen prepare to rescue your husband and his co-worker, your daughter breaks free from your grip, forcing her way through the crowd to one of the draegermen. She tugs on his sleeve. When he looks down, she pleads, “Please bring my daddy home.”

They descend, your daughter’s face and words branded onto their hearts. What you don’t know is that they expect to find the two men dead. They battle through the carnage to the place they suspect they’ve been trapped. Sure enough, there they are, partially buried, but somehow still alive. An hour and a half later, they reach the surface, the last two men strapped to stretchers. That’s when the Earth rumbles again beneath your feet. The Allan shaft has exploded for a second time.

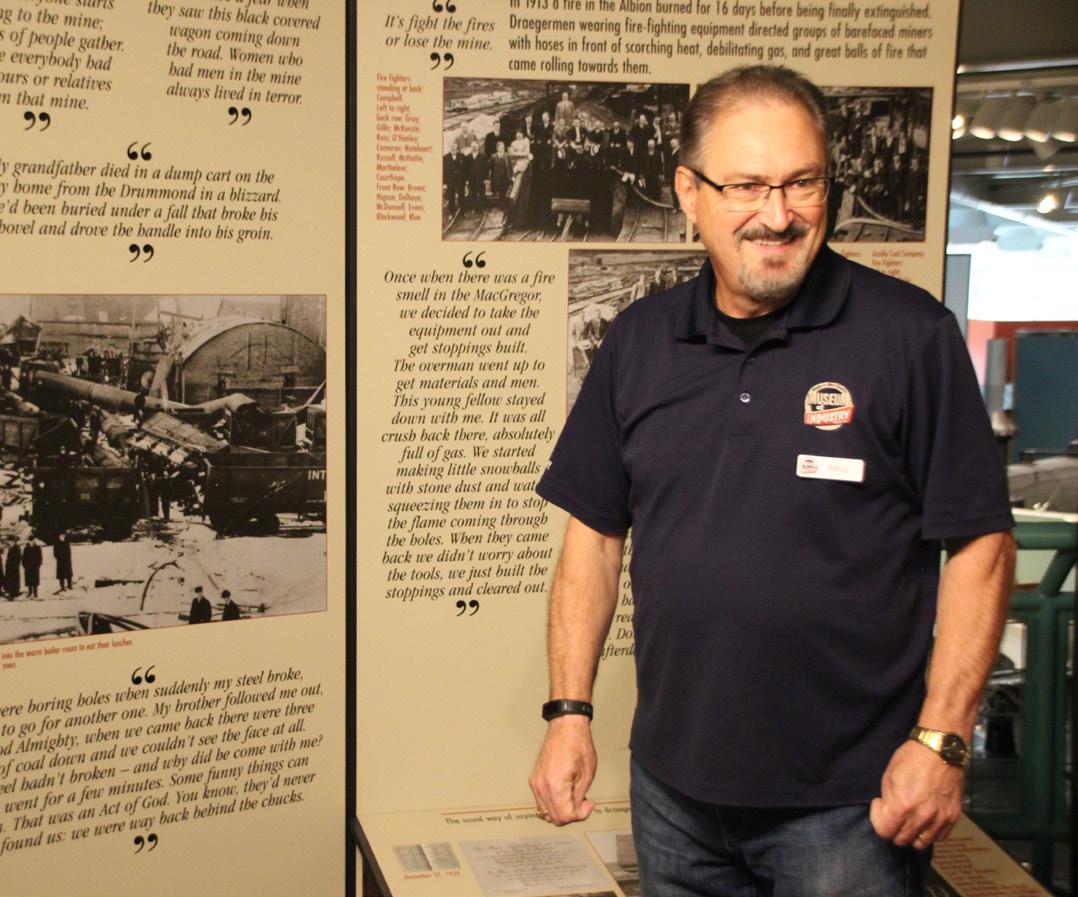

THE MUSEUM OF INDUSTRY Paul Laland, interpreter in the Coal and Grit Gallery

Big history

With this story of disaster and rescue, interpreter Paul Laland, a retired history teacher, has his audience of half a dozen visitors to the Coal and Grit Gallery at the Museum of Industry hanging on his every word. The museum—a National Historic Site—stands on the very ground where in 1827, a British company established an English coal mining community and built a web of mine shafts and roads that followed the coal seams through the Earth’s crust.

The story of the Allan mine disaster of 1950 ends well, but nearly all of the 30 mines that operated here exploded sooner or later, many with staggering losses of life. Most recently, the heartbreaking Westray disaster of 1992 killed 26 miners. For personal reasons, Laland is absolutely dedicated to his work of telling these stories.

“One of the deadliest was in the Drummond Mine,” Laland says. “That’s where my grandfather was killed in 1873. It took 60 men and boys, some of them very young.”

Laland is renowned as the museum’s master storyteller, but he’s not the only one. The museum’s smoothly flowing layout pulls visitors effortlessly from one exhibit to the next. We duck out of the cramped and dim Coal and Grit Gallery to enter Atlantic Canada’s largest exhibit gallery. When I see the Samson and the Albion, I understand the need for all this space. The Samson— imported from Britain in 1838—is the oldest surviving steam locomotive in Canada and one of the oldest in the world. The Albion is right behind at possibly the second oldest in Canada. These gleaming hulks once transported coal to the coast. Today, they’re a favourite of kids and railway buffs.

Many of the museum’s exhibits often involve a hands-on activity and always a few stories by the interpreter. I print a few flyers at the printing press and challenge myself to keep up on the assembly line. At the fully operational quarter-sized sawmill,

Brier Island Lodge.

• Try original Pictou County Pizza, a brown sauce variety and specialty of

Acropole Pizza in Westville. • Enjoy exciting, contemporary dining at East Avenue in downtown New

Glasgow. • Take the kids for a treat at Corina’s

Ice Cream Parlour in New Glasgow. • Stay at the Holiday Inn Express right off the Trans Canada, not far from the museum. • For a complete holiday, stay at the

Pictou Lodge Beach Resort 17 kms from Stellarton.

an interpreter mills up some miniature lumber by guiding small logs through the saw blade. Deeper into the museum, we find two women in a replica living room typical of a local home. They’re in the middle of major quilting projects, but take time to chat. We check out the inside of a traveling woodworking bus used for training carpenters and look around a completely rebuilt period beauty salon.

Outside, we emerge into sunshine 70 years after those rescued miners were so thankful to see the open sky above their heads. The Allan shaft was sealed a year after that 1950 explosion. The only original part of the mines stands before us, the three storey cut stone monolith that housed the Cornish pump over the shaft of the Foord pit. At 1,000 feet, it was once the deepest on the continent, thanks to the mighty 260 horsepower steam engine pump that kept it free of water.

Even as we depart, the Museum of Industry is telling us stories of big machines and big history.

THE MUSEUM OF INDUSTRY

Brier Island Whale and Seabird Cruises

Brier Island’s Original and #1 Chosen Whale Watch Dedicated to Research & Education Since 1986!

PO Box 1199 223 Water St., Westport, Brier Island, Nova Scotia B0V 1H0

1-800-656-3660 www.brierislandwhalewatch.com

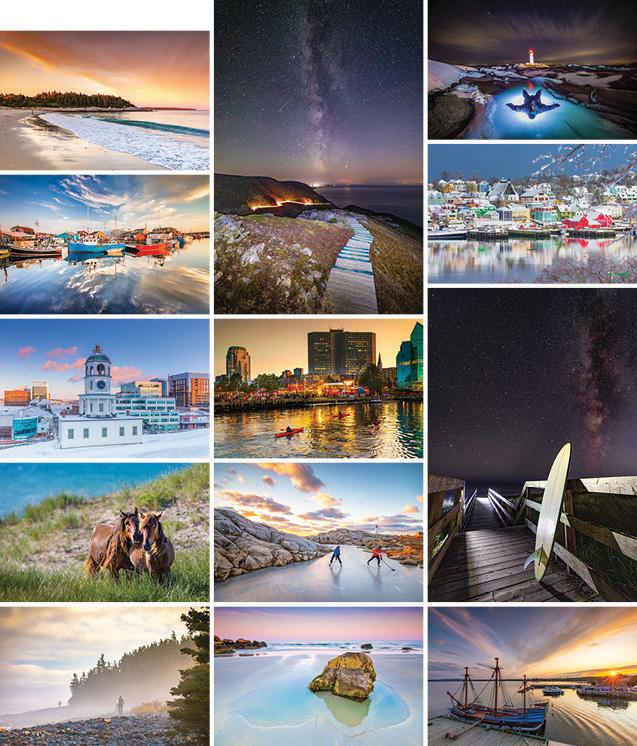

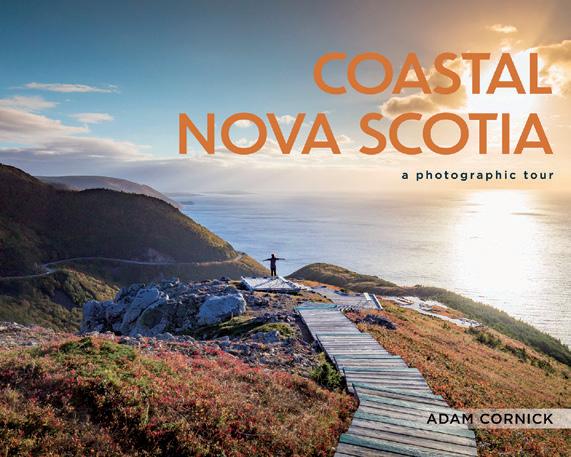

COASTAL NOVA SCOTIA

A Photographic Tour by Adam Cornick

$34.95 | photography 978-1-77108-887-9

With 100 full-colour images and insider tips on the must-see spots and hidden gems in each coastal region, Coastal Nova Scotia: A Photographic Tour takes readers on a round-the-province visual trip to places many have never seen—and gives us compelling reasons to add a few new locations to our own bucket lists.

“A FUN TRIP AROUND THE PROVINCE WITH A GREGARIOUS ENTHUSIAST.” – BILLIE MAGAZINE