4 minute read

The missing chapter

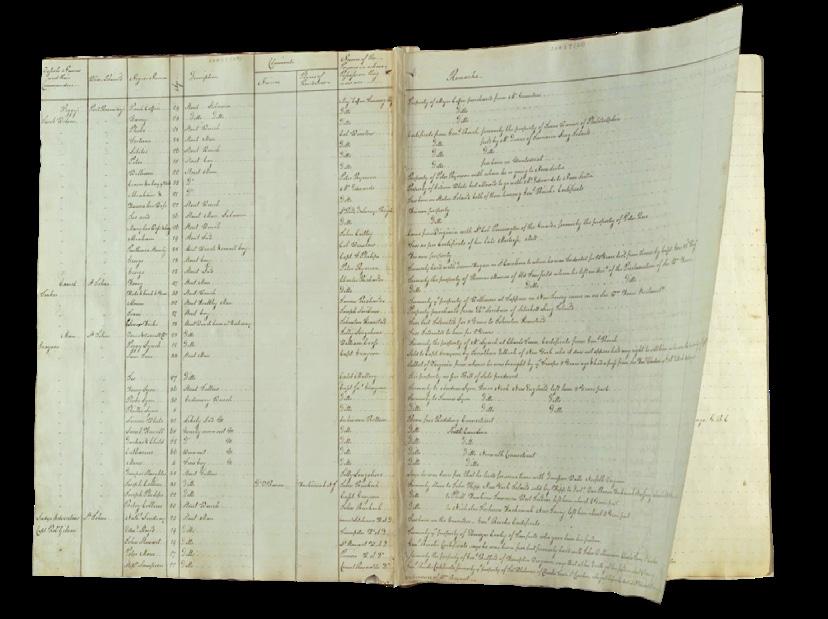

The glass floor and room at the Black Loyalist Heritage Centre in Birchtown, near Shelburne. Inset: the original Book of Negroes.

A visit to the Black Loyalist Heritage Centre

BY DARCY RHYNO

I’m looking at what first appears to be logs neatly stacked in the shape of an “A”. The gaps between the logs are tightly packed with moss. In the front, a doorway gapes. It’s a beautiful autumn day, the sunlight shining through the remaining leaves to dapple the ground and granite boulders with warm light. This peaceful current scene belies a troubling history.

“This is a replica of a pit house,” says my guide. “With limited time, supplies and provisions, they had to come up with some way to get through Nova Scotia’s winter.”

Jason Farmer is the Senior Interpretive Guide at Birchtown’s Black Loyalist Heritage Centre, and a ninth-generation

Black Loyalist descendent. “With influence from the Mi’kmaq and skills learned during the American Revolution, they would come up with this type of subterranean shelter. Working with what little they had—trees, leaves, rocks and moss—they would start by digging a hole, then place a makeshift roof over the top. The door would be a piece of canvas or animal fur.”

I climb in through the doorway. The air is dank, earthy. Chinks of light through the cracks between the logs offer enough light to make out the few features inside. The logs are a roof over a shallow impression in the ground dug to create benches that must have served as beds. A pile of stones suggests a crude fireplace. Various mushrooms grow from the ceiling festooned with spider webs.

“Many Black Loyalist families lived in a pit house like this for the first few years.” Some, adds my guide, lived in such shelters from 1783 to 1791. “Eight years is a long time to be living in a hole in the ground. I don’t know about you, but I wouldn’t be able to survive one night in one of these things.”

Black Loyalists had no choice but to build such structures. After the end of the American Revolution, many Africans and

DARCY RHYNO

DARCY RHYNO DARCY RHYNO

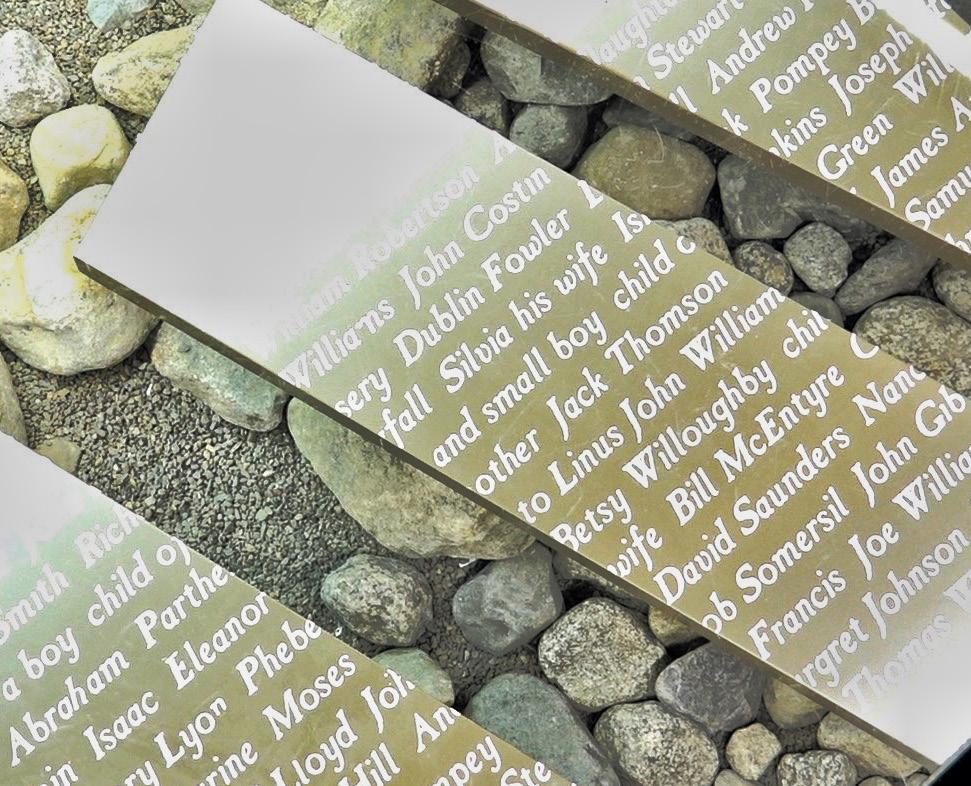

Clockwise from top: Closeup of the museum’s glass floor; plaques at the burial grounds; guide Jason Farmer at the Pithouse.

DARCY RHYNO a view you will always remember… a taste you will never forget!

those of African descent either escaped or were freed from slavery. British forces helped about 3,500 flee to what they were told was freedom in the northern British colonies, the territory that would become Canada. But when thousands of these Black Loyalists arrived in the newly-established Port Roseway (today, it’s known as Shelburne) on Nova Scotia’s South Shore, they were met with extreme prejudice and violence. Prevented from settling in town, they were forced to this rocky location at the end of the harbour, that came to be called Birchtown. It wasn’t named for the trees that grow here, but for British General Samuel Birch, who protected Africans in New York City from recapture by their former owners. Later, he signed most of their Certificates of Freedom and supervised the creation of the Book of Negroes, the document that recorded the names of the people his forces helped escape to Shelburne and other ports in the Maritimes.

The pit house sits on a small rise on a short trail called “Aminata’s Walk.” It’s named for the fictional main character in The Book of Negroes, by Canadian novelist Lawrence Hill. Through the journey of his character, Hill tells the story of slavery, a story set partly in this very place because Birchtown is the missing chapter. The story of slavery begins in Africa where millions were kidnapped and shipped mostly to the Caribbean and to South and North America, where they were forced to work. Many either escaped or were released, eventually finding their way back to Africa where the British assisted in the creation of the country Sierra Leone and its capital, Freetown.

Inside the new Black Loyalist Heritage Centre next to the trail, the main exhibition room is flooded with light from the wall of windows, illuminating exhibits beneath the glass floor. The experience of walking onto the floor is in striking contrast to ducking into the dim, damp pit house. Beneath the floor, the names of all those former slaves in General Birch’s Book of Negroes are engraved on metal. A few of some 16,000 artefacts uncovered on these grounds are displayed beneath the floor and in glass cases around the room. On the back wall you’ll see several touch-screen monitors for viewing chapters in the history of slavery, including the kidnapping of Africans, their life in the Americas, the road to freedom, and modern-day Birchtown where more than 200 years of Black Loyalist history