6 minute read

Treading lightly

Walking barefoot among Keji’s petroglyphs

STORY AND PHOTOS BY DARCY RHYNO

Nick Whynot stands barefoot and proud—his tattooed arms crossed— on rocks covered in messages from the past. All around him are dozens of images scratched into the exposed bedrock here on the shores of Kejimkujik National Park. This is the second largest collection of petroglyphs in Canada and a direct link between the man standing before me and his Mi’kmaw ancestors who left their marks here over the past hundreds, perhaps thousands of years.

Whynot begins his tour of the Keji petroglyphs by pointing out tiny but detailed images of tall ships under sail. “I particularly love these two,” he says. “They actually took the time to put in the cannons. It’s like a Spanish galleon.” The Parks Canada tour guide is a resident of the nearby Wildcat Reserve—a member community of the Acadia First Nations band—so he feels in his bones the importance of these images.

“That would have been something to behold when you’re paddling to PEI or Newfoundland in a birchbark craft, and you see a big ship like that.” As he speaks, I think of stories we tell ourselves today of UFOs and visiting aliens. Pondering the impact of strange, unidentified sailing objects by his ancestors, Whynot continues. “Those are stories you’re going to bring back and draw for people, seeing these massive ships with people on them.”

He’s been living and learning the ways of his people for most of his life. He grew up hunting and trapping around the national park with his father and uncles. Another

Wildcat resident, Todd Labrador, offers birchbark canoe building workshops every summer at Keji, and Whynot has participated. “I also took up knife making with my uncle,” he tells me. “Now, I do knapping. That’s taking stone and turning it into projectile points and tools.”

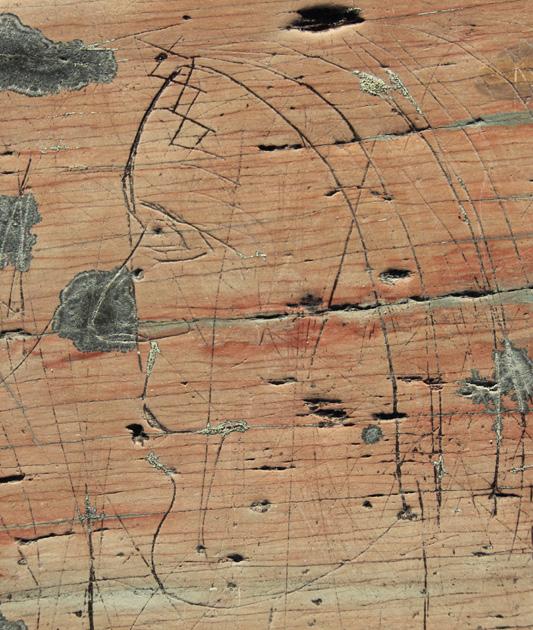

Monument at the entrance to the petroglyph trail in Kejimkujik National Park. Opposite page: wetting a petroglyph for better viewing.

Hunting tools, endemic animals and ceremonial feathers function as portals to Whynot’s cultural past. Kneeling beside the lake, he splashes water on a badly worn petroglyph and points out the shape of a woman in traditional dress. “As it dries, you will be able to make out a single feather,” he says. “What she would put on her hat, that was hers, so this is essentially a portrait.”

Because the area got more rain than usual this summer, the water level in the lake is high. “There’s a nice one out on the tip there,” Whynot tells me, pointing past the end of the rock. “It’s a caribou. It’s in relatively good shape, but it does spend a lot of time underwater. It usually doesn’t come out until July or August. This year it was only out for a week.” This is one of five sites where a total of 500 petroglyphs have been found in the park, all on the shores of Kejimkujik Lake, a stopping place for Mi’kmaw paddlers on

their way between the coast and the Lake Rossignol area, now flooded behind dams. Whynot refers to this part of Keji as a transportation hub.

“You can gather resources here,” he says. “There was fishing. There was hunting. Back at Eel Weir Bridge, there were several eel weirs. We know they had a large production. People speared the eels. Someone on shore was skinning them and putting them on racks to smoke. Dried fish and the smoked eels would have been important because that’s going to be food stores through the fall and winter until they can get a moose or caribou.”

While animal petroglyphs are easy to distinguish, other etchings harbour unsolvable mysteries. I place my bare feet on either side of one of them, the profile of a man wearing a hat and holding what looks like a shield. Whynot tells me the Mi’kmaw call him the French soldier or sometimes the French missionary, but no one really knows for sure who he is. Parts of the figure are faded, but it remains a significant individual petroglyph for the possibilities. “We know the first written form of our language was actually brought here by a French missionary,” Whynot explains. “It was a series of symbols. There were actually Bibles printed entirely in the symbol form. I think there’s still a couple of them around.” I take a photo of the figure between my bare feet. Removing our shoes, Whynot tells me, is both a sign of respect and a practical measure because pebbles stuck in treads can scratch the soft slate. Parts of the site are heavily damaged from erosion and vandalism. Some of the marks gouged into the rock over the petroglyphs are more than a century old. Some are much more recent. Whynot has seen the desecration in action. He’s watched paddlers read the warning signs on the line of buoys meant to keep people away, then land on the rocks anyway.

These petroglyphs make Kejimkujik a National Historic Site, the only National Park in Canada with the double designation. But the cultural value of these images doesn’t seem to protect them as well as they should. So-and-so loves so-and-so is scratched over engravings of the first tall ships ever seen through Indigenous eyes on this continent, chillingly accurate for those gunports. And yet, as if echoing 500 years of post-contact history and the resilience of Indigenous peoples across North America, these petroglyphs persist.

Other Mi’kmaq experiences at Keji

• Take part in the birchbark building workshop with Todd Labrador.

In 2022, Labrador will build an ocean-going canoe for the Canadian

Canoe Museum in Peterborough,

Ontario. • Visit the birchbark canoe built by

Todd Labrador at the Visitor Centre. • Check out the Mi’kmaq encampment site and wigwam at Merrymakedge

Beach. • Watch for scheduled programs like guided walks and slide presentations on Mi’kmaq history and culture. • Take a tour with interpreters in the voyageur canoe and paddle with a traditional hand carved wooden

Mi’kmaq paddle. • Hike or bike to Eel Weir bridge at the foot of Kejimkujik Lake and imagine the busy fishing and preserving operation Nick Whynot describes. • Bike the new Ukme’k cycling trail.

Ukme’k means “twisted” in Mi’kmaq.

The name was inspired by the winding path this trail takes along the Mersey River. POP-UP HALIFAX

Brad Hartman

$29.95 | pop-up giftbook 978-1-77471-026-5

SMALL STRUCTURES OF NOVA SCOTIA

Spaces of Solitude, Necessity, and Simplicity Jessie Hannah