56 minute read

News

Multi-Layered Narratives

TACITA DEAN

In a 2018 interview with Royal Academy, Tacita Dean (b. 1965) stated that she “didn’t care about the long run, caring only about now.” Dean is a British European artist born in

Canterbury, currently living and working between Berlin and

Los Angeles (where she was the Artist in Residence at the

Getty Research Institute from 2014 to 2015). She is perhaps one of the best-known female artists of her time – a nominee for the Turner Prize in 1998, winner of the Hugo Boss Prize in 2006, and a Royal Academy of Arts electee – exploring a sense of history, time and place, as well as the quality of light and the tangible essence of analogue film reels.

Dean works across 16mm film, photogravure, sound installation, gouache, artist books and found objects, with an impressive portfolio that transcends categorisation by genre, medium or interpretation. Glenstone Museum, Maryland, opens an installation comprising three monumental chalkboard works – Sunset (2015), When first I raised the tempest (2016) and The Montafon Letter (2017). Affixed to the pre-cast concrete walls of the pavilion, these large-scale, multi-panel chalk-on-blackboard drawings create a panoramic effect as visitors descend into the gallery space.

Glenstone comments: “These drawings operate between the didactic and the sublime, depicting – amongst other things – the sea, sky, ships and rocks. Executed on Victorian-era chalkboards, the works manage to evoke both a classroom setting and the murkiness of photographic negatives. The process of erasure and punctuation innate to the medium are in dialogue with the scene and the indecipherable text peeking through the many layers of chalk. There is also a performative element at play: the artist adjusts the works with each installation, changing words and modifying shading.”

Dean began working on Sunset (2015) after moving to Los Angeles in 2014. Shrouded in thick cloud, the sunset manages to be both still and moving – impending darkness looms. The motif is inspired by the California sky and recalls the work of Romantic-era British landscape painter John Constable. When first I raised the tempest (2016) takes its title from Act Five in Shakespeare’s The Tempest, in which Prospero responds to the spirit Ariel: "I did say so, when first I raised the tempest. Say, my spirit, how fares the king and ’s followers?"

Lightning strikes through the dark, ominous clouds; their forms conjure the supernatural storm and subsequent shipwreck at the heart of the play. Spanning 32 feet, the work is Dean’s widest blackboard drawing to date. The title of The Montafon Letter (2017) alludes to a series of 17th century avalanches in the mountainous Montafon valley of Austria, from which one priest miraculously survived.

The scale of these works, alongside their allusions to both tangible and images landscapes, places the viewer at the centre of a dramatic and multi-layered historical narrative. “The process of erasure and punctuation innate to the medium are in dialogue with the scene and the indecipherable text peeking through the many layers of chalk. There is a performative element at play.”

Glenstone Museum, Maryland Opens 6 May

Spanning the Climate Crisis

RISING TIDE

The ocean is vast, covering 140 million square miles, equivalent to 72 per cent of the Earth’s surface. According to the UN, more than 600 million people (around 10 per cent of the world’s population) live in coastal areas that are less than 10 metres above sea level. Nearly 2.4 billion people (about 40 per cent of the population) live within 100 km of the coast.

Regardless of whether you live close to or far away from the coast, marine life (particularly its biodiversity) affects every living thing. From the economy (ocean ecosystems are estimated at $3-6 trillion per year) to health, sustenance and nutrition, right through to available land (the number of displaced individuals is thought to rise to 1.2 billion people by 2050), the issue is intrinsic to the human experience.

As we approach 1.5°C of warming (and more realistically beyond, with COP26 meeting in November this year to discuss the parameters laid out in the 2016 Paris Agreement and goals for net zero emissions), the planet begins to tip over into irrevocable change – feedback loops of collapse and destruction. According to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, by 2100, global mean sea level rise is projected to be around a 10th of a metre lower at 1.5°C as opposed to 2.0°C. Just 10 per cent of a metre puts a further10 million people at risk from the related effects.

Rising Tide, on view at the Museum of the City of New York, brings together a collection of photographs from Netherlands-based Kadir van Lohuizen (b. 1963) – works that examine the consequences of rising sea levels caused by the climate crisis, through photography, video footage, drone images and sound work. The pieces range from Greenland to Bangladesh; Miami to New York, documenting the fine lines – both literally and figuratively – between land and sea, the present and the future. Lohuizen notes: “In my reportage I have tried to provide globally balanced coverage. I travelled to Kiribati, Fiji, the Carteret Atoll in Papua New Guinea, Bangladesh, the Guna Yala coastline in Panama, the United Kingdom and the United States. In these different regions, I not only looked at the areas that are, or will be, affected, but also where people will likely have to relocate to.”

He continues: “What is often forgotten is that before seas flood land permanently, the sea water intrudes much earlier at high tides, thus making once-fertile land no longer viable for crops, and drinking water brackish and undrinkable. Coastal erosion, inundation, worse and more frequent coastal surges and contamination of drinking water mean increasingly that people have to flee their homes and lands in a growing number of locales across the world. Almost no one with whom I have spoken wants to move; they simply have no other choice as conditions worsen.” As we look ahead to the agreements sent out this November, this show is undoubtedly an important part of the climate conversation. “What is often forgotten is that before seas flood land permanently, the sea water intrudes much earlier at high tides, thus making once-fertile land no longer viable for crops, and drinking water brackish and undrinkable.”

MCNY, New York Opens 16 April

mcny.org

The Shape of Inspiration

BARBARA HEPWORTH: ART AND LIFE

“Barbara Hepworth (1903-1975) is one of the most important artists of the 1900s, with a unique artistic vision that demands to be looked at in-depth. Deeply spiritual and passionately engaged with political, social and technological debates in the 20th century, Hepworth was obsessed with how the physical encounter with sculpture could impact the viewer and alter their perception of the world.”

Eleanor Clayton is a curator at The Hepworth Wakefield and a Hepworth specialist. She is the editor and contributing editor of Howard Hodgkin: Painting India, (2017) Lee Miller and Surrealism in Britain (2018) and author of Viviane Sassen: Hot Mirror (2018). Her latest title, Barbara Hepworth: Art & Life (Thames & Hudson, May 2021) coincides with the major exhibition, charting work from the 1920s to the early 1970s.

The exhibition opens with an introduction to the artist, showing the three key sculptural forms she returned to repeatedly through a variety of different materials – from bronze casting and gray alabaster to marble, silver, Burmese wood and limestone. A detailed look at Hepworth’s childhood in Yorkshire also includes some of her earliest known paintings, carvings and life drawings as she began to explore the human form. Here, audiences can see how Hepworth was a proponent of direct carving, combining an acute sensitivity to the organic materials of wood and stone, with the development of a radically new and abstracted formal language. Moving on chronologically, a large section considers Hepworth’s development of abstraction in the 1930s, including Three Forms (1935), created shortly after she gave birth to triplets, an event she felt invigorated her work towards a bolder language of geometric form. The show then takes various pathways into the 1950s and 1960s, before later work inspired by space exploration and Neil Armstrong’s first steps on the moon – a hinge-point for the artist. Hepworth famously noted: “Man’s discovery of flight radically altered the shape of our sculptures, just as it has altered our thinking.”

The show will be a huge event in the artistic calendar, with

Barbara Hepworth retrospectives famously bringing in hundreds of thousands of viewers (the Kröller-Müller Museum in

Otterlo, Netherlands, reported a gallery record of 113,275 visitors in 2016). Further to this, pre-pandemic, the Yorkshire

Sculpture Triangle (comprising The Hepworth, Henry Moore

Institute, Leeds Art Gallery and Yorkshire Sculpture Park) had begun to report record numbers also, bringing more than one million visitors between April 2017 and March 2018, and over one million to the 2019 Yorkshire Sculpture International (June-September). This is an unmissable exhibition – for Hepworth fans and both Yorkshire and non-Yorkshirebased attendees. This is an exhibition which viewers from every region (restrictions permitting) should have a chance to view and enjoy, with dates stretching well until 2022. “Audiences can see how Hepworth was a proponent of direct carving, combining an astute sensitivity to the organic materials of wood and stone, with the development of a radically new and abstracted formal language.”

The Hepworth, Wakefield 21 May - 27 February

Rethinking Innovation

GERMAN DESIGN 1949 – 1989: TWO COUNTRIES, ONE HISTORY

“It has been over 30 years since German Reunification, yet the two sides of the country have still not truly merged. The same essentially goes for the telling of German design history – they’re mostly kept separate. With the exception of the main protagonists of post-war modernism such as Dieter

Rams, Hans Gugelot, and others centered around the Ulm School of Design (HfG Ulm), many accounts of German design generally lose traction after the 1940s, whilst many others diminish or omit the East German position altogether.

We wanted to pick up where such narratives leave off, filling in the blanks of design history in a divided Germany by reintroducing forgotten – or virtually unknown – design practitioners from both East and West and situating them within the canon. We’re in a place as a society (and as institutions) where the re-telling of history to include more of its participants is not just important, but imperative.”

Vitra Design Museum’s latest show, German Design 1949–1989: Two Countries, One History, breaks with simplistic stereotypes and presents a differentiated view of design from the two sides, exploring ideological and aesthetic differences as well as parallels and interrelations across the landscape. Vitra Design Museum's Curator Erika Pinner continues: “In the last 15 years, there has been a growing interest in the private life and material culture of countries in the Eastern

Bloc. The German Democratic Republic (GDR, East) is only one of them, but it provides an especially fascinating case of ‘double history’ with its western neighbour, the Federal Republic of Germany (FRG, West). Here, we’re looking at two opposing political systems of socialism and capitalism, yet the same language and culture, and the same toolbox of design principles and approach from pre-war modernism, as well as the same dark legacy of fascism and destruction to overcome. There’s generally an interest in finding out more about these material possessions, as they are reminders of a culture to which they are inherently linked. Yet the exhibition isn’t just about the East, it’s about including it within the bigger story of German design, of which it is inevitably a part.”

The museum presents over 250 items, ranging from iconic pieces of furniture and lamps to graphic, industrial and interior design, right through to fashions, textiles and assorted personal ornaments. Key practitioners include Klaus Kunis, Dieter Rams, Erich Menzel and Ernst Moeckl. In a tumultuous year, defined by shifting politics in the global east and west, the curatorial team hopes that this show encourages visitors to leave clichés behind. Pinner concludes: “Depending on where they grew up – whether it’s East or West Germany, or somewhere else – viewers will undoubtedly recognise iconic design objects. I hope this show reframes their understanding of German design, but beyond this, I hope some of the objects might even shift their idea of what design is today.” “Viewers will undoubtedly recognise iconic objects. I hope this show reframes their understanding of German design, but beyond this, I hope some of the objects might even shift their idea of what design is today.”

Vitra Design Museum, Weil am Rhein Until 5 September

design-museum.de

A Trailblazing Light Artist

HEINZ MACK

ZERO was an artist group founded in Düsseldorf by Heinz Mack (b. 1931) and Otto Piene (1928-2014) – described as a “zone of silence and pure possibilities of a new beginning.” The collective was formed in 1957, in reaction to the European movements of Tachisme (non-geometric abstract art characterised by spontaneous brushwork, drips and scribble marks) or Art Informel (gestural abstract painting). ZERO was concerned with the development of kinetic art – making use of light primarily, as well as space and motion – de-emphasising the role of the artist, looking to viewer participation.

Kunstpalast celebrates the 90th birthday of Heinz Mack, illuminating the innovative and revolutionary spirit with which Mack unlocked “new spheres of thinking and working outside academic requisites.” The selection includes around 100 works tracing key stages in Mack’s career, such as his studies at the Academy of Art Düsseldorf, the ZERO period, as well as seminal light-based environmental art, which has since influenced numerous high-profile practitioners the world over.

Many of the pieces demonstrate Mack’s strong interest in exploring “pure light” in “unspoiled” areas, especially in the vastness of the African and Arabian desert, and in the perpetual ice of the arctic. In a 2017 interview with The Art Newspaper, Mack noted: “The landscape should be free, clean, untouched – it should be just nature in a very pure way.” This can be seen in the Sahara Project – installations of “artificial gardens” in the desert, including wing-reliefs, cubes, mirrors, sails, banners and monumental light-stelae.

There is a kind of utopian quality to Mack’s work in this way, with mirrored platforms and blocks protruding from sand dunes or bodies of water. Some of the images on show at Kunstpalast will look uncannily similar to the strange metal monoliths that began materialising in 2020: beginning in Texas and moving through to California, Romania, the Isle of Wight and the Netherlands, amongst other locations.

Licht Architektur (1976) for example, includes reflective cubes surfacing from the water, like a city resting on a lone glacier. The piece is part of a series installed in the arctic. In the 1970s, Mack became intrigued by plexiglas-bodies, light-flowers, prismatic pyramids, ice crystals and fire-rafts. These works were documented in Expedition into Artificial Gardens, which Mack issued with Thomas Höpker (b. 1936).

Other projects on show include Heinz Mack with Silver Foil in The Field of Sand Dunes – Sahara, which depicts the artist waving a reel of foil on an open plane, letting the light reflect and refract off the surface. Mack resembles an abandoned cosmonaut. Images like this also feel incredibly timely, especially considering the Perseverance landing on Mars on 18 February – the location point now named after science fiction writer Octavia E. Butler, who wrote: “Mars is a rock – cold, empty, almost airless, dead. Yet it’s a heaven in a way.” “There is a kind of utopian quality to Mack's work, with mirrored platforms and blocks protruding from sand dunes or bodies of water. Some of the images at Kunstpalast will look uncannily similar to 2020's strange metal monoliths.”

Kunstpalast, Düsseldorf Until 30 May

Living on a Post-Truth Planet

PHILIPPE BRAQUENIER

“From high altitudes, or even from space, the true shape of the

Earth can easily be seen. Its dimensions can be measured; its radius of curvature in all directions can be calculated; the imperfections and departures from sphericity are directly observable by our instruments. If you travel far enough away from Earth, you can observe an entire hemisphere at once, even watching the planet rotate on its axis in real time.

“At right around 12,700 kilometers (7,900 miles) in diameter, our world is undoubtedly a sphere. Of course, it actually is quite round: a near-perfect sphere, to better than 99% precision. If you leave Earth’s surface, it’s impossible not to see the true shape of the Earth, as it›s been unavoidable since we first travelled high enough to observe our planet’s curvature.” (Ethan Siegel, Five Impossible Facts That Would Have to Be True if the Earth Were Flat, Forbes, 24 November 2017). Even still, there’s an increasing number of “flat-Earth” believers – those who think the Earth exists as a disk, drawing on beliefs from classical Greece, and the Bronze and Iron Ages.

Philippe Braquenier (b. 1985) is a Belgian photographer fascinated by knowledge; intrigued by how it is collected, used, shared and stored. Braquenier’s practice encourages discourse about humanity’s obsession to deal with information – especially when data is becoming ever more omnipresent, yet all the more unseen. His latest series, Earth not a globe, is named after a volume written by one of the 19th century’s most extreme conspiracy theorists, Samuel Birley

Rowbotham. The work explores communities who believe continents float on an endless ocean: the North Pole at the centre of the Earth, the sun and moon above the Earth.

Jasper Bode, Director and Founder of Ravestijn, notes: “Conspiracy theories are increasingly popular thanks to social media. With the coronavirus, conspiracy theories have gained even more strength. These have lead people to believe that they are in possession of a secret that the allpowerful want to hide – and that the rest of the world is just too blind to see. It is interesting to see how conspiracists mix knowledge and supposition, science and belief, fact and fiction, to take only what serves their purpose, even if it means contradicting themselves. In an era of post-truth, this project poses a reflection on the conspiratorial power of images.”

Featured images centre around light, gravity, reflections and rotations, as well as propaganda vans, star trails, experiments in buoyancy and density, and rocket launches. The image below, Planes Help to Prove the Plane (2018), depicts pale pink corrugated iron suspended amongst a near-barren forest. A deep blue sky contains silvery strands stretching upwards, seducing the viewer through its science. Bode concludes: “You could describe Braquenier’s work as aesthetically pleasing documentary – that helps the audience to question conspiracy mechanisms at work in society today.” “With the coronavrius, conspiracy theories have gained even more strength. These have lead people to believe that they are in possession of a secret that the allpowerful want to hide – and that the rest of the world is just to blind to see.”

Ravestijn Gallery, Amsterdam Until 10 April

theravestijngallery.com

10 to See

RECOMMENDED EXHIBITIONS THIS SEASON

Moving into the spring season, key shows and events consider the essential role that natural ecosystems play on our rapidly changing and warming planet. Elsewhere, galleries examine the development of visual culture – through the lens of post-WWII publishing and the AI age.

1Wisdom and Nature Christie's, Online | 6-27 April christies.com 2021 is a momentous year for the environment. The 26th UN Climate Change Conference of the Parties takes place this November in Glasgow – a summit to accelerate action towards the goals of the Paris Agreement. The Le Ciel Foundation is built on the belief that the crisis has been caused by a systemic separation between the material and spiritual. Christie’s London hosts a fundraising exhibition in aid of the foundation, with 49 artists contributing in order to protect and integrate ancestral indigenous knowledge into the ecosystems of western society.

2Circulation(s) Online | Until 2 May festival-circulations.com Since its inception in 2011, Circulation(s) Festival has showcased the work of over 382 artists and attracted over 300,000 visitors. It is a hub of creative talent from across Europe, providing a stepping-stone for artists to interact, collaborate and present their work to thousands of attendees through various platforms and strands. This year, the festival goes completely online, promoting meetings between artists and the public across a variety of digital formats. The 2021 programme includes 33 artists across 12 different countries, from Russia to Austria.

3Ed Ruscha: OKLA Oklahoma Contemporary | Until 5 July oklahomacontemporary.org “Oklahoma looms large in Ed Ruscha’s work as a source of inspiration from which his unique perspective on America was formed. In 1956, he embarked on the first of many road trips – which he would frequently make reference to in his art. Ruscha has repeatedly been quoted in the years since saying everything he’s done was already part of him when he left Oklahoma at 18; his mythos is tied to Americana and the open road." OKLA includes more than 70 works from Ruscha's prolific 60-year career, exploring the role of the artist's home state.

4Borealis – Life in the Woods Fotomuseum Den Haag | Until 3 October fotomuseumdenhaag.nl/en The Boreal Region forms part of a band of vegetation circling the entire northern hemisphere, boasting an endless expanse of coniferous forests, mires and lakes. Over four years, photographer Jeroen Toirkens (b. 1971) and journalist / broadcaster Jelle Brandt Corstius (b. 1978) visited various locations in the boreal zone, seeking stories from the land and the people who live there. Toirkens’ images bear witness to the region's mythical appeal as well as its complex present-day realities, from conservation efforts on Hokkaido island to Siberian forest fires.

5Illusion: The Magic of Motion MOPA, San Diego | Until 16 May mopa.org “Our brains can’t see, or hear, or taste. They sit in the dark, making up a world informed by electrical stimuli from our sense organs. The act of perception is an act of prediction, of estimation. What we consciously perceive is our brain’s ‘best guess’ at what the outside world is like.” (Laurence Scott, Picnic Comma Lightning, 2018) MOPA, San Diego, considers the inception of photography through experimentation with light, optics and perception. Key pieces include shadow play and anamorphosis, all highlighting the illusion of motion. 1

3

4

8

9

6Grief and Grievance New Museum, New York | Until 6 June newmuseum.org Polls from last summer estimate that between 15 million and 26 people participated in the Black Lives Matter demonstrations in the USA – making the protests the largest in American history. The lessons we have learnt, and are still learning, about systemic racism are immense. New Museum’s Grief and Grievance is an inter-generational exhibition collating 37 artists who address the concepts of mourning, commemoration and loss as a direct response to the emergency of racist violence experienced by Black communities across America.

7Format Festival 2021 Derby City Centre & Online | Until 11 April formatfestival.com Format International Photography Festival is a biennial event held in Derby, UK, founded in 2004. This year's edition heads online, with a dynamic programme of digital curation, talks and portfolio reviews. Key themes for the 2021 exhibitions include Picturing Lockdown: Photography in the Pandemic; Matrix: Fluid Bodies, Unlimited Thoughts; East Meets West; Notes on Distance; Unperson Portraits of North Korean Defectors; and Honesty and Disguise. Mixed reality, performance, images and film explore mass isolation and the concept of home.

8Modern Look: Photography and the American Magazine Jewish Museum, New York | Until 11 July thejewishmuseum.org.uk Both Harper’s Bazaar and Vogue’s early art directors – Alexey Brodovitch and Alexander Liberman – were European émigrés, born in Belarus and Kyiv respectively. These seminal photographers moved to New York in the aftermath of WWII, building careers in magazines through visions of innovation, inclusivity and pragmatism. The Jewish Museum compiles a variety of images, layouts and cover designs for some of America’s best-known publications, considering the photographs that transformed American visual culture from 1930 to 1960.

9Hito Steyerl: I Will Survive Centre Pompidou, Paris | (Check online for new dates) centrepompidou.fr “In the future, 100% of all humans will die. Access this zone at your own risk and don’t complain later.” So warned Hito Steyerl (b. 1966) when viewers downloaded an augmented reality app for Serpentine’s 2019 exhibition Power Plants (11 April - 6 May). Steyerl’s moving image works often follow this unsettling tone, as well as concerns over militarisation, surveillance migration and the role of media in a globalised world. Her latest show, held at Centre Pompidou, re-imagines the facts of the world in the age of social stimulation technologies.

10Artes Mundi Online | Winner Announcements 15 April artesmundi.org Artes Mundi celebrates artists who engage with social realities and lived experiences. This year’s six nominees (including Carrie Mae Weems, Beatriz Santiago Muñoz, Meiro Koizumi,

Prabhakar Pachpute, Firelei Báez and Dineo Seshee Bopape) express diverse global narratives, encouraging meaningful thought on cultural identity, global gentrification and the psychological dimensions of 21st century conflicts. Nigel Prince, Director, notes: “These artists prompt us to critically reflect on what it means to exist in this world, in all its complexity.”

1. Oliver Barnett, Kalandreamer, 2017. Archival print on Hahnemühle Photorag. 130 x 158 cm. Courtesy the artist. 2.© Sofia Yala Rodrigues, Playing with Visual Fragments (2020). Courtesy of Festival circulation(s) 2021. 3. Desert Gravure, 2006. Photogravure. 21 1/4 X 24 3/4 in. (54 x 62.9 cm) Ed. 4/30. Collection of Jordan D. Schnitzer. © Ed Ruscha. Photo courtesy the artist and Gagosian. 4. BOREALIS, Buryatia, Russia, August 2019 – Damage from a forest fire in Siberia © Jeroen Toirkens. 5. Phillip Leonian, Untitled #20 from the series Mini Cine, 1973, printed 2020, inkjet print. Courtesy of Leonian Rosenbaum Charitable Trust. © Leonian Rosenbaum Charitable Trust. 6. Rashid Johnson, Antoine’s Organ, 2016. © Rashid Johnson. Courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth. 7. Brian Griffin, Big Bang. Courtesy of Format Festival. 8. Martin Munkácsi, Woman on Electrical Productions Building, New York Worlds Fair, New York, 1938. Gelatin silver print. F.C. Gundlach Collection, Hamburg. Artwork © Estate of Martin Munkácsi, Courtesy. Howard Greenberg Gallery, New York. 9. Hito Steyerl, Hell Yeah We Fuck Die, 2016 Vue d’installation au LBS West, Münster, 2017 Skulptur Projekte Münster 2017, 10.06 – 01.10.2017. Courtesy: Hito Steyerl, Andrew Kreps Gallery, New York, Esther Schipper Gallery © Photo: Henning Rogge. 10. The Angels of Testimony. Image Credit: Meiro Koizumi, The Angels of Testimony, 2019. Commissioned by Sharjah Art Foundation. Courtesy the artist, Annet Gelink Gallery, Amsterdam and MUJIN-TO Production, Tokyo.

Symbiotic Architecture

Living in Nature

FOUR BILLION PEOPLE LIVE IN URBAN AREAS, A FIGURE SET ONLY TO INCREASE. THE ONLY WAY FORWARD IS TO WELCOME THE ENVIRONMENT INTO THE BLUEPRINTS.

As Covid lockdowns got underway last year, Tove Jansson’s 1972 novel The Summer Book suddenly became relevant again. Though written by the Moomins creator nearly half a century before, it now reads as a primer for isolation, detailing how an elderly artist and her granddaughter whiled away a summer on a remote Swedish island. “Rereading it now, this book feels like a survival guide,” noted nature writer Melissa Harrison in The Guardian in April. In July, TED included The Summer Book on its list of summer recommendations.

The characters in Jansson’s book are alone for much of the book, but what comes across isn’t their lack of social contact. Instead, the novel is rich with life, filled with the movement of the tides and winds around the lonely summerhouse, or the tiny shoots and mosses that grip onto the barren rocks. The pair become so delicately attuned to the ecosystem that the landscape becomes another character entirely. “Moss is terribly frail,” reads one section. “Step on it once and it rises the next time it rains. The second time, it doesn’t rise back up. And the third time you step on moss, it dies. Eider ducks are the same way – the third time you frighten them up from their nests, they never come back.”

It’s expected, then, to see a Swedish cabin in Phaidon’s latest title Living in Nature – Johan Sundberg Arkitektur’s Summerhouse Solviken, which was completed in 2018 in Mölle, Sweden, and described by editors as having “simplicity, modesty and wholehearted empathy with its surroundings.” In fact, Living in Nature even includes a series of whimsical triangular cabins inspired by the Moominhouse, set on stilts in the woods in Gjesåsen, Norway, by Espen Surnevik in 2018.

Following on from other titles in Phaidon’s groundbreaking Living in series (deserts, water, mountains and more) this new publication includes designs from all over the world, ranging from the modest to the much more substantial. These are houses in which the organic world has been the primary consideration, informing decisions about everything from the plot size to the materials, views, carbon footprint and geometry within the landscape. Phaidon’s editors note: “These projects take challenging terrains and climates into account, but they do not aim to tame or colonise nature.”

Take Bivouac Luca Pasqualetti, built by Roberto Dini and Stefano Girodo, in Morion Ridge, Aosta Valley, Italy, in 2018. Teetering on a mountain ledge more than 3000 metres above sea level, it’s a simple shelter commissioned to popularise forgotten climbing routes – robust enough to withstand temperatures as low as -20°C, winds up to 200km per hour, driving rain and hail, and snow. Even so, it’s constructed around a metal basement and held in place by guy ropes, which means it can be removed without leaving a trace.

Luciano Giorgi’s Casa Falk, 2008, in Stromboli, Aeolian

Islands, has a similar sense of organic luxury, though it’s set in the most uncompromising of places. Wedged between dark volcanic cliffs and the Sciara del Fuocco, a blackened lava scar caused by volcanic eruptions down the northern flank of Mount Stromboli – one of the world’s most active volcanos – it draws on both the environment and the existing architecture, quite literally. Casa Falk is modelled on the typical, white stucco of local homes. However, it also once belonged to Swiss artist Hans Falk; when Giorgi was

Previous Page: Roberto Dini and Stefano Girodo, Bivouac Luca Pasqualetti, 2018, Morion Ridge, Aosta Valley, Italy. Picture credit: Stefano Girodo.

Left: Luciano Giorgi, Casa Falk, 2008, Stromboli, Aeolian Islands, Italy. Picture credit: Tommaso Sartori. commissioned to update the building, he restored a fireplace Falk had hewed from concrete and lava stone.

Other locally sourced materials are abundant, with black lava-stone from Mount Etna making up the flooring, and other raw ingredients including chestnut wood from Sicilian forests and marble from nearby Carrara. These materials may be local but they’re also magnificent, and the colour scheme is as rich. The upper floors of Casa Falk look out over the sea and the volcano. Dark bronze window frames are designed to interact with the environment, naturally oxidising with time to change colour. The elements here are undeniably powerful, and the architect has given them space.

Vandkunsten Architects took a similarly sensitive approach to materials with the Modern Seaweed House in Læsø, Denmark, in 2013. The building is on an island in the sea bay of Kattegat, which is famous for its eelgrass-thatched roofs. Unlike wood, seaweed has always been plentiful there, and it also needs no farming because it simply washes up on the shore. In addition, it’s intrinsically waterproof – a great insulator – and durable, lasting about 150 years. First used by the Vikings, eelgrass is attracting renewed interest amongst architects today. Vandkunsten maximised on this innovative – yet age-old – material by stuffing the eelgrass into string-net bags to create bolsters, which they attached in lengths to the façades and roof of the building.

They also packed it into timber crates, placed behind walls and under floors for insulation. Since the house accommodates two families, seaweed’s soundproofing properties were an added bonus. By working in this way, the architects helped ensure the house has a negative carbon impact – that’s to say, the almost exclusive use of organic building materials, causes the amount of CO2 accumulated within the house to exceed that which was emitted during the production and transportation of those materials.

Brazil’s Catuçaba House, designed by Studio MK27 and completed 2016, also uses local resources, in this case partly for practical reasons – the house is built on a steep hillside in a remote corner of São Luíz do Paraitinga, making transportation a little difficult. Instead, the architects excavated soil to create adobe walls and clay tiles for the interiors, keeping the house cool in summer; the side walls made from rammed earth. The bulk of the structure was prefabricated using FSC-certified cross-laminated timber, which was easy to assemble in this tricky location.

Catuçaba House also features solar panels, a wind turbine and a rain-collection system – though this means that, like three other projects presented in the book, it’s completely off-grid. In this, the project hints at another, compelling theme in Living with Nature – the need to create houses capable of withstanding extreme conditions. When Rob Mills first designed Ocean House in Lorne, Australia, he wanted to build with timber, for example, but a period of bush fires and changes in planning laws meant he had to use concrete.

Meanwhile, the Peruvian Casa Patios, 2018, by Rama Estudio, looks more like the archetypal eco-village – quite literally built into nature, dug into the earth with a greenroof garden on top. The walls are made of bahareque, a material similar to adobe, with straw and soil from the site packed into wood and metal-mesh frames; outer flanking walls supporting the roof are made of heavy stone. “Solid, sheltered, and grounded, Casa Patios is totally in tune with the surrounding landscape,” state Phaidon’s editors.

These houses have a self-sufficient edge that suggests something a little more radical about design and our conception of nature – Covid has taught us that the future is always uncertain, but the effects of the climate emergency are already with us. Ice is melting everywhere and global sea levels already rising at 3.2mm per year (according to National Geographic's current online statistics). Sea levels are expected to rise between 26cm-82cm by the end of the century, meaning floods will become more likely; hurricanes are likely to become stronger and so too are droughts, and this inevitably means more wildfires. Undoubtedly, everyone will be affected by this destruction, not merely those living on the coast (plus knock-on political changes wrought by, for example, the rapid spike in climate refugees).

In the future, buildings must be able to handle these conditions; designs will need to work in cities as well as in beautiful, remote locations, because – unless new mutations of Covid push us to flee city centres, or depopulate the world to an apocalyptic level – more people will be living in towns. In fact, the European Commission expects some 85% of the world’s population to live in urban centres by 2100, meaning that the urban population will increase from less than one billion in 1950 to nine billion by the turn of the century. “The human race has become a species of town and city dwellers, existing in a landscape of paved streets and structures that keep the natural world at bay rather than belong to it.”

In the next few years, the relationship between humans and local ecosystems won’t be – and can no longer be – an afterthought. It’s therefore fitting (even reassuring) that Living in Nature ends with a project based in Wargrave – a village near London built around both the River Thames and one of its tributaries, the River Loddon. Narula House, completed in 2020 by John Pardey Architects, sits on a flood plain but (like the Moomin-inspired cabins) raised on stilts; when the Thames swells, the house remains well above the waters.

Though Living in Nature is just as appealing as a coffee table book – filled with glossy pictures – the title quietly proposes a radical new approach to the environment: one that’s built on mutual respect and sovereignty. It’s an attitude that hasn’t always held sway in the west but, as Jansson’s novel suggests, this sentiment has always been there; especially in other cultures, with Hinduism (approximately 900 million) and Japanese Shintoism (approximately 90-100 million individuals) both drawing their deities from the natural world, urging a humble regard for other forms of life.

These beliefs informed the projects of Kazunori Fujimoto, the architect behind the 2019 House in Ajina in Hiroshima – a place with more reason than most to be wary of human hubris. Fujimoto’s house faces the sea but also a torii gate, a traditional entrance to a Shinto shrine which symbolically marks the transition from the mundane to the elevated sacred. “I thought it was a courtesy to the shrine to face each other with a proper posture,” he says. “I think you need an attitude of gratitude for being kept in nature – architecture should rationally intervene in the minimum.”

Fujimoto’s words echo the titles of both Living in Nature and The Summer Book, all three suggesting the only route forward being a decentralisation of humanity. Nature is defined as all living things both human and non-human, and it has become evident that, much as we may fight to separate ourselves from the other, we must integrate into ecosystems in a more responsible way, or they will continue without us.

Right: Kazunori Fujimoto Architect & Associates, House in Ajina, 2019, Hiroshima, Japan. Picture credit: Kazunori Fujimoto.

Words Diane Smyth

Living in Nature: Contemporary Houses in the Natural World is published by Phaidon

Playful Geometry

Michael Oliver Love

Shapes have huge cultural value, and are some of the first bits of knowledge we acquire as human beings – helping us to identity and organise visual information. They are defined in broad categories depending on the number and length of edges, from triangles, quadrilaterals and pentagons to more complex sphere-shaped objects like cylinders and cones. Michael Oliver Love lives and works in Cape Town, South Africa. His style is centred on an interest in organic lines and fluidity in nature, tapping into the intriguing flow between forms and the physical connection between landscapes and bodies. Ridged lines mark the slip faces of sand dunes, figures play within concentric circles, and rippling, asymmetrical pools of yellow are painted on walls. Love is also the founder of Pansy Magazine – a publication that dismantles the preconceived categories of masculinity and femininity. pansymag.com | michaeloliverlove.com.

Michael Oliver Love, Rock Solid. Styling: Peter Georgiades Grooming: Sarah Whiteside. Models: Collins Blaise, Seid Mahamat, Aza Mhlana, Avies Newton & Osei Clinton. Courtesy of the artist.

Michael Oliver Love, Shapes in Nature 01. Courtesy of the artist.

Michael Oliver Love, Lemonade. Models: Tobi Oloko & Lebu Mlumkisi. Courtesy of the artist.

Michael Oliver Love, Red Flesh. Model: Anilton Cabral. Courtesy of the artist.

Michael Oliver Love, Send To. Models: Pivot & Osei. Courtesy of the artist.

Michael Oliver Love, Maroon in Motion. Model: Oliver Roslee. Courtesy of the artist.

Michael Oliver Love, Smile. Model: Toudry Wangi. Courtesy of the artist.

Michael Oliver Love, Embodiment. Beauty: Michelle-Lee Collins. Models: Kitso Kgori & Lebu Mlumkisi. Courtesy of the artist.

Michael Oliver Love, Bananarama. Beauty: Sarah Whiteside. Model: Sethu Matanga. Courtesy of the artist.

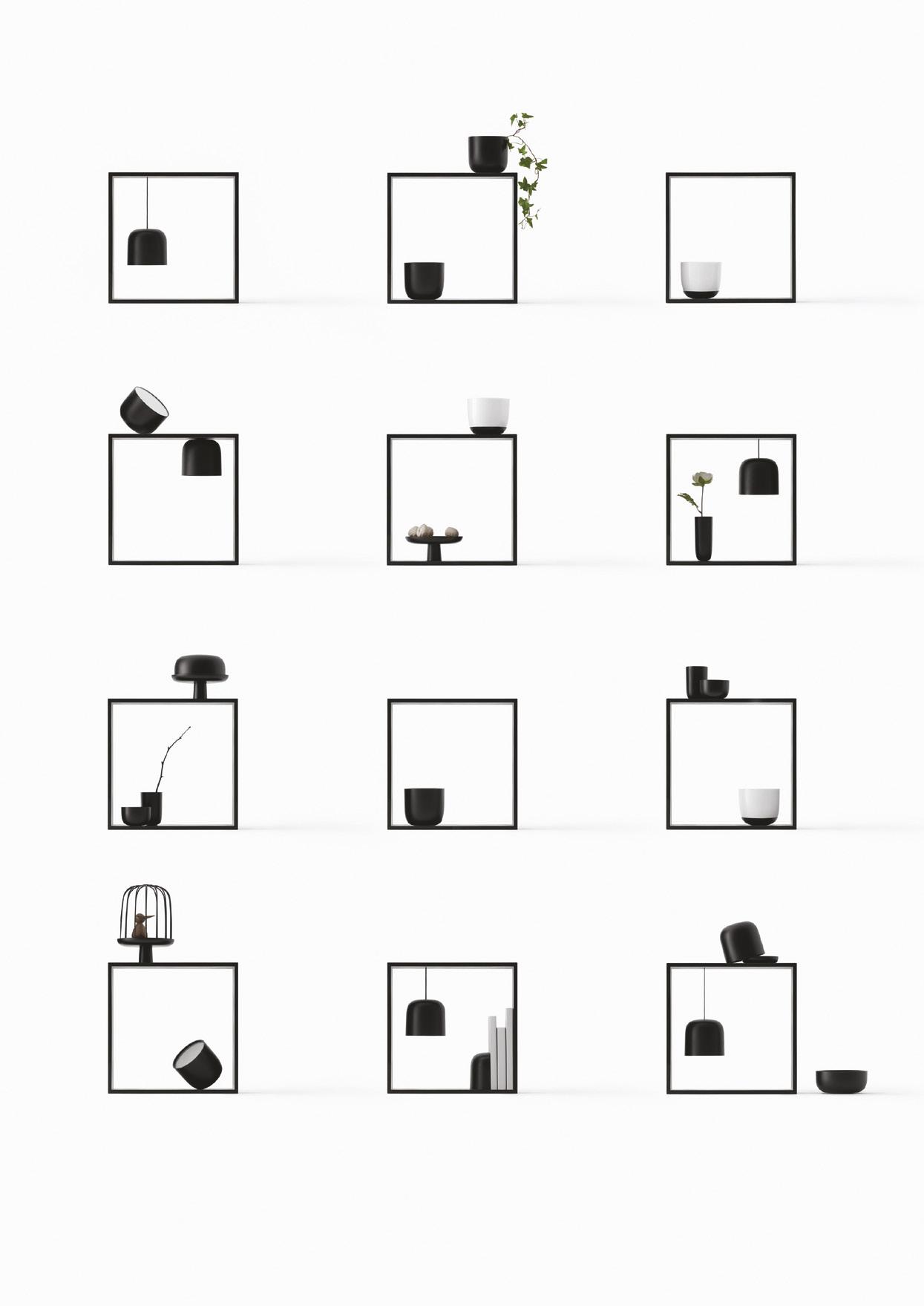

Spatial Minimalism

Nendo

JAPANESE DESIGN STUDIO, NENDO, IS KNOWN FOR A PROLIFIC OUTPUT AND PLAYFUL STYLE. WE UNPACK ITS APPEAL IN AN AGE OF PARED-BACK, MONOCHROME AESTHETICS.

When the National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne, planned to stage a major exhibition of work by MC Escher in 2018, the cutting-edge Japanese design studio Nendo, with its pared-back but playful aesthetic, proved the perfect match for the Dutch graphic artist, known for mathematical tricks of the eye. However, the resulting collaboration, titled Escher X nendo | Between Two Worlds, went far beyond what the curators had imagined. Nendo’s founder Oki Sato (b. 1977) took the simple form of a house and repeated it in myriad ways.

It was there when visitors entered, a dramatic interlocking pattern on monochrome wallpaper. It followed in the shape of a tunnel through which audiences moved from one section of the show to another, and a seating area from which to contemplate artworks on the walls. Other houses existed as fragmented black frames, which, only at certain angles, appeared to merge into a whole. Finally, a chandelier made of 55,000 tiny houses threw geometric shadows into every edge of the room, expanding the definition of the gallery.

“Sato understood from the outset that a ‘collaboration’ with MC Escher could allow a move outward – beyond the paper and the frame, beyond the wall and the floor – to manifest the thematic concerns and inspirations encountered within Escher’s work – sensorial, spatial and architectural,” writes NGV’s director, Tony Ellwood, in the foreword to a new monograph of the studio’s work since 2016, published by Phaidon. “Sato looped iconography and spatial experience in order to subtly question traditional notions of the relationship between art and design.” At a time when many artworks are visible in digital reproduction at a mere click, Nendo’s approach to exhibition design asserts the preeminence of the gallery or museum as a site for unique physical encounters.

Nendo’s relationship with NGV dates back to 2016, when Ellwood came across the studio’s installation 50 Manga Chairs at Friedman Benda, New York, and snapped up all 50 for the gallery’s collection. With a mirrored finish, each Manga chair was inspired by graphic elements taken from the iconic Japanese comics, from speech bubbles to lines indicating characters’ movements, sweat and tears. Sato has described Escher’s work as residing somewhere "between the possible and the impossible" and the same could be said of these chairs. Like optical illusions, the pieces toy with perspectives, conflate dimensions and subvert our preconceptions about how objects or materials behave.

This, in turn, informs a number of the studio’s other designs. In the installation Into Marble, produced for Marsotto Edizioni during 2018 Milan Design Week, marble appears like a liquid substance into which tables seem to dissolve. Another collection of chairs, Watercolour, takes its cue from painting. The metal chairs have been painted matte white then daubed with blue ink; their surface recalls the texture of paper, which has been cut and folded – like an expansive blank page.

Oki Sato founded Nendo in 2002 when he was just 25 – fresh from a degree in architecture at Waseda University. Based between Tokyo and Milan, Nendo has since then established a reputation as a multi-award-winning, groundbreaking, global design studio, with a prodigious, multidisciplinary output that ranges from furniture to retail spaces, branding, stationary, toys, a portable toilet, pet accessories,

Previous Page: Gaku, Flos, 2017. © nendo Left: Flow, 2017. © nendo

multi-way zippers, cheesecakes, vases, in-flight tableware for Japan Airlines, rugby team uniforms, keys and jewellery. The roughly 30-strong team works on several hundred designs at once – and Sato is personally involved in each one. “The more ideas I think of, the more ideas I come up with.

It is like breathing or eating," he told Dezeen in 2015. “If I focus on only one or two projects, I guess I can only think about one or two projects. When I start thinking about working on close to 400 projects, it relaxes me. It's like a top; when it is spinning very fast it is stable and when it starts to spin slowly it starts to get wobbly.” The dazzling breadth of Sato’s work is revealed in the Phaidon publication. Nearly 500 pages lay bare the evolution of the studio’s practice, steered by Sato’s consistently trailblazing vision.

Ironically perhaps, given its wildly prolific output, Nendo’s approach is minimalist at its core, tending towards clean, continuous forms constructed using few materials with a restricted colour palette of black and white, or calming hues such as greys, blues and pastels. Japanese minimalism advocates using only what is essential, favouring unfussy shapes, neutral tones and unadorned, natural materials that give light and space room to breathe.

Its principles are embodied in the concepts of “Wabisabi” and “Ma” – with roots in Zen and Mahayana Buddhism, Wabi-sabi recognises impermanence and imperfection. Aesthetically, this means that simplicity, asymmetry, weathering and careful craftsmanship are prized. “Ma”, meanwhile, translates as “gap” or “pause”, and emphasises the importance of negative space. In Nendo’s work, these tenets can be seen in a form of subtraction; often the crux of the project is found in what’s removed, reduced or sliced out. Meji, for example, reimagines a bulky umbrella stand as a sleek grey cuboid structure, with subtle grooves that are only noticeable when used to insert an umbrella.

By reducing visual and spatial clutter, minimalism encourages us to slow down and to focus on the minutiae: the rich complexity of life that might otherwise go unnoticed, whether it's shadows dancing across a wall, or the view of falling leaves through a window. Minimalism grounds us in the physicality of the present, and, the argument goes, opens a space for our minds to fill up with imagination rather than being overloaded with information. That’s why

Montessori educational children’s toys are simple and functional. It’s why Steve Jobs had a wardrobe full of hundreds of identical black turtlenecks – courtesy of Japanese fashion designer Issey Miyake, whom Sato cites as an abiding influence. The repetition of this uniform, Jobs believed, was liberating. By eliminating the choice of what to wear, he could direct limited time and energy elsewhere.

Sato agrees: “I don’t think that special moments create special ideas,” he told Domus in an interview during Salone del Mobile 2019. “I think that boring moments do: the everyday routine – like waking up, brushing your teeth – it really resets my mind, I can stay blank and be centred. When you work on so many projects you might lose yourself. By doing the same everyday things I am able to become zero again and have a fresh mind always.”

These ideas have become incredibly popular in recent years, not only as design choices but as lifestyles. Perhaps it’s a reaction to capitalist excesses, rampant consumerism, digital dissemination, economic crises and climate catastrophe. The simple life holds great appeal. A rising appe-

tite for stripped-back aesthetics underpins much of 21st century lifestyle trends – from Scandi Hygge practices to digital detoxes; the market in vintage mid-century modern furniture, to the tiny house movement. Decluttering guru Marie Kondo, whose 2014 book, The Life-Changing Magic of Tidying Up: The Japanese Art of Decluttering and Organizing, urges us to “keep only those things that speak to the heart, and discard items that no longer spark joy” – a contemporary take on that William Morris adage “have nothing in your house that you do not know to be useful, or believe to be beautiful.” Indeed, after selling more than 11 million copies of her book, Kondo launched the Netflix reality show Tidying Up with Marie Kondo, which is now available to view in nearly 200 countries over the world.

The idea of “joy” is important here, because, without it, minimalism can sound a tad austere – another self-help stick with which to beat ourselves. Nendo takes its name from the Japanese word for “modelling clay” or “Play-Doh” and there’s a ludic, sometimes almost mischievous spirit that runs throughout their designs, often tapping into tradition or nostalgia around Japanese culture. The Coen Car is a fleet of mobile children’s playground equipment which, though in trademark monochrome, draws on the visual trend of Kawaii or “cuteness” that has become a mainstay of the “Cool Japan'' brand, whilst Grid-Bonsai is a 3Dprinted bonsai tree that can be trimmed to a shape of the individual’s liking. Here, function and fun go hand-in-hand.

Also like Play-Doh, Nendo’s projects are often intended to be flexible, allowing users to reshape or adapt pieces to their own unique tastes or changing needs – from modular sofas to whiteboards that double up as office dividers, as well as folding phones, sliceable trophies and a magnetic desk lamp that can be broken down into its constituent parts and recomposed in multiple ways. If any one thing can define contemporary culture, it’s heterogeneity. Individuals want to assert their own identities, customise items and carve out a world that responds to and works for them.

Where once British teens gathered around the TV on a Thursday evening to watch Top of the Pops and compare notes the next day, they now discover new music through the algorithms of Spotify recommendations. In Nendo’s world, this translates as giving agency to those who interact with their projects. In their curation for Inspiration or Information? A 2018 exhibition of traditional Japanese art at Tokyo’s Suntory Museum of Art, individuals were offered the choice of two routes through, one of which showed the artworks together with contextual details, the other left them to have a purely intuitive, emotional response.

Ultimately, this is what “good design” is about – not things or even ideas, but people. Tenri Station Plaza CoFuFun is an early example of everything that makes Nendo distinctive. A multi-use development containing bike hire, a cafe, a stage, meeting spaces and more, its unembellished white, saucer-like curved structures are a nod to the ancient tombs or “cofun” of Tenri, a city in the Nara Basin. At every turn are flights of steps. Or perhaps they’re benches. Or shelves. The point is they’re all of these things and none of them. They're design tinder. Really, what Nendo produces isn’t objects and buildings, rather personal experiences: opportunities to pause and wonder at what’s hidden in the everyday. After all, as MC Escher once put it, he, she or they “who wonders, discovers that this, in itself, is wonder.”

Right: Breeze of Light, Daikin, 2019 Picture credit: Takumi Ota.

Words Rachel Segal Hamilton

Nendo: 2016-2020 is published by Phaidon

Obscure Portraiture

Alma Haser

The term “collage” was first coined by Cubist Georges Braque (1882-1963) and Pablo

Picasso (1881-1973), from the French word “coller” or “to glue.” From here, a movement emerged – one based upon avant-garde assemblages, fractured forms and deconstructed subject matter. Since then, many practitioners across the globe have been inspired to dismantle visuals, literally “piecing” new pictures together whilst drawing attention to the fragile materiality of images. Alma Haser’s (b. 1989) puzzle-piece portraits negotiate the boundaries between the real and the manufactured. These intriguing and unsettling images are disruptions of the human form as we know it today, asking intriguing questions about the manipulation, construction and obfuscation of the self in the 21st century. In an age of hyper-self-awareness, increased video connectivity and social media profiles, these photographs reflect upon the shape-shifting nature of identity today. haser.org.

Alma Haser, Hands Pixelated from the series I Always Have To Repeat Myself . Courtesy of the artist.

Alma Haser, Wexin, commissioned by Infringe magazine. Courtesy of the artist.

Alma Haser, Wife, from the series Husband and Wife. Courtesy of the artist.

Alma Haser, Alina, commissioned by Infringe magazine. Courtesy of the artist.

Alma Haser, Will and Amy, Private commission. Courtesy of the artist.

Alma Haser, Lee and Clinton (1) from the series Within 15 Minutes. Courtesy of the artist.

Alma Haser, Tia, a coder from the Annie Connons organisation, a collaboration with Maria de Rio for Wired US. Courtesy of the artist.

Alma Haser, Mayflower, a coder from the Annie Connons organisation, a collaboration with Maria de Rio for Wired US. Courtesy of the artist.

Alma Haser, Hermon and Heroda (2) from the series Within 15 Minutes. Courtesy of the artist.

Forging New Pathways

Beauty and the East

CHINA’S MOST FORWARD-THINKING ARCHITECTS ARE REPURPOSING STRUCTURES TO OFFER A NEW LANDSCAPE THAT IS BOTH CULTURALLY RESONANT AND SUSTAINABLE.

The kaleidoscope of stairwells and doorways that crowd the interiors of the Other Place guest house, on the banks of the Li River in Guilin, serves as a metaphor for the period of tumult and opportunity amongst China’s architectural community: it’s not clear where the route forwards lies, but the state of confusion is somehow enticing. The Maze and Dream guest house suites (pictured here) were modelled on MC Escher’s impossible landscapes – designed to trick the eye.

The scale of recent and projected building work in China is jaw-dropping, as the China editor of Wallpaper*, Yoko Choy

Wai-Ching, relays in her introduction to Beauty and the East. “In the last 70 years, the number of cities in China has risen from less than 60 to 672. By some estimates, almost half of the world’s construction will take place in China in the coming decade.” And that’s in a country which already “builds 22 billion square feet of new floor space each year – if it was laid out flat, that would be 1.3 times the size of the entire footprint of London.” Infrastructural development on this scale brings obvious challenges. China’s ongoing reliance on energy-intensive materials such as steel and concrete has grim implications in an era of climate crisis. More practically speaking, as Choy notes pithily in interview, “it doesn’t make sense any more to build shoddy stuff in China.”

In other words, there are also questions about the quality of construction that takes place when the pace of expansion is so fast, as summarised by the head of iconic firm Amateur Architecture Studio Wang Shu in his foreword to the Gestalten book. “Until the end of the 1990s there were essentially no independent architectural practices in China as the stateowned mega design institutes dominated.” As the country became rapidly urbanised “these institutes were drawn into a whirlpool of large-scale developments – the number of projects was giddying, and the requests relentless ... It was almost impossible to produce good quality architecture.”

Although the number of private firms has multiplied over the last two decades, the legacy of that first, dizzying, “experimental” era of Chinese architecture is evident in the impossibly truncated planning and construction schedules still foisted on most firms. Wang Shu points out that a proposal “conventionally takes half a year.” But Chinese clients “will only allow two months, so things proceed in feverish haste. Very often, drawings are rendered without a thoroughgoing design proposal. In truth, most constructions in China start before the completion of the drawings.” Roughcast spaces, misplaced switches and sockets, irregular rows of windows – in short, “bad” architecture – are all symptomatic of the fact that “everything was designed and constructed in a hurry.”

Against this backdrop, however, an alternative paradigm has emerged, powered by the rise of private firms of varying sizes and types, albeit in a space still mediated by the demands of the state. Wang Shu’s Amateur Architecture Studio is the great pioneering force here. Responsible for some of the most iconic recent Chinese building designs, such as the Ningbo Historic Museum and the Fuyang

Cultural Complex, the studio has forged an aesthetic based on repurposing materials and structures, as well as a reliance on traditional construction methods, and forging links with local historical and environmental heritage. What’s more,

Previous Page: Studio 10, Photo Chao Zhang, Beauty and the East, gestalten 2021.

Left: Studio 10, Photo Chao Zhang, Beauty and the East, gestalten 2021. when Wang Shu became the first Chinese architect to win the prestigious Pritzker Prize – the so-called “Nobel Prize of Architecture” – in 2012, he placed not just Amateur Studio but the country’s broader design achievements under the global spotlight for the first time. “From Wang Shu I see a new start,” Choy muses positively, “a starting point for people to look at Chinese architecture overall, and city planning; he has also inspired a lot of new generations.”

Pressed on the other most significant firms of the stillblossoming independent era, Choy mentions practices with a mixture of western and national influences. MAD Architects, whose founder Ma Yansong is Yale-educated, is one of the first Chinese firms to secure major European commissions, and is now designing the FENIX Museum of Migration in Rotterdam. “He is the first to be entrusted with a public cultural building on the continent. It’s a huge milestone.” By contrast, the founder of LUO Studio, Luo Yujie, studied in China and has specialised in rejuvenating rural villages. “From his work you see something authentically and organically Chinese.” Choy is referring to works such as LUO’s Party and Public Service Center in Yuanheguan Village, Hubei Province, a beautifully spare functional structure created by repurposing the abandoned steeland-concrete foundations of a half-finished residential project – adding a timber-framed upper storey.

Choy’s selection of two such different visions is not accidental. She pushes back against the idea of any common thread underpinning contemporary Chinese architectural philosophy: and given the sheer size and diversity of the country’s population, its diffuse geographies and social milieux, and an increasing openness to international influences, she clearly has a point. Perhaps the only common contextual factor to the projects in Beauty and the East is awkward interdependence with the state, which is still relied upon for conceptual validation, as well as legal and economic gate keeping. As Choy puts it, “to execute new concepts, you need to get local government on board.”

The country’s built environment is a subject upon which the authorities continue to weigh in heavily. In 2015, the national State Council issued a decree on the desirable qualities of urban architecture: “suitable, economic, green and pleasing to the eye,” in contrast to the “xenocentric, peculiar” developments of the previous decades. The projects in the state’s crosshairs might have included Beijing’s

China Central Television headquarters (known as the “Giant

Underpants”), designed by the Dutch firm OMA in 2012. The year before the directive was issued, State Premier Xi Jinping had famously called for an end to “weird architecture,” with such extravagant foreign projects surely in mind.

This level of government control has undeniable up-sides too. For example, it has allowed funding to be channelled away from sprawling megalopolis developments such as along the Pearl River Delta, ensuring – as far as possible – that regional towns and villages also remain lively economic and cultural centres. The achievements of Amateur Architecture Studios, whose many projects have encouraged a sense of pride amongst depleted rural communities, are unavoidably entwined with this narrative. So too are the fortunes of other firms such as DnA, whose renovation of ancient villages in Songyang County – funded by the local government – involved planting a cluster of brand new industrial structures across the region, produced on

time-honoured construction principles: a process referred to in this publication as “architectural acupuncture.”

This brings us round to the dazzling portfolio of projects in Beauty and the East, an encyclopaedic survey compiled by inhouse editors at Gestalten with Choy’s advisement, in which the reuse of existing materials and structures and reliance on traditional methods are recurring motifs. Think of Atelier tao+c’s Capsule Hotel and Bookstore in Qinglongwu Village, Zhejiang Province, built into a traditional rural structure with mud walls and a timber-framed shell, with inner spaces remodelled and a glass-panelled gable-end added to create a gorgeous, sun-flooded chapel for browsing and reading.

Or take Studio Zhu-Pei’s Imperial Kiln Museum in Jingdezhen, which incorporates a set of long, low arched vaults mirroring the structures of the abandoned kilns on whose sites they sit, using bricks reclaimed from the old ovens. Then there’s anySCALE’s Wuyuan Skywells Hotel, a renovated 300-year-old mansion with a modern penthouse and original wooden decorations restored by a local artisan. In another breath HyperSity Architects’ refashioned cave dwellings (yaodong), in the Loess Plateau region, are created using rammed-earth; whilst O-office Architects’ Lianzhou Museum of Photography is built on the site of an old sugar warehouse.

In other cases, modern structures are inserted into spaces between older buildings, like PAO Studio’s “plug in” steel capsules, that slot into the central courtyards of antique urban siheyuan dwellings; or their Shangwei Village PlugIn House, designed to rejuvenate dilapidated dwellings in villages engulfed by the expansion of Shenzhen on the Pearl River Delta. The examples are myriad, and the outcomes of this impulse to “make new” are often remarkably scintillating.

Again, for Choy, we shouldn’t take this as evidence of a “national style” so much as common limits on resources and time. Like LUO Studio’s community centre, many of the designs reflect the scant materials, technology and workforces available to deliver a brief on a tight schedule. “In villages like Qinglongwu, where the Capsule Bookstore was built, architects face a lot of constraint in terms of availability of materials, building technologies and so on. The reality is that often the clients aspire to good design in these areas, but they offer little time and budgets.” It’s overcoming these restrictions – not an interest in combining the traditional and the modern, or eastern and western influences – that will define the eventual look and feel of a building: “for me meaningful architecture just has to solve problems.”

All of the examples listed above might prompt readers to risk a definition of contemporary Chinese architecture as ecologically driven, sensitive to cultural imagination and memory, and mindful of the need to reuse rather than tear down and start from scratch. China continues to consolidate its position as the central player in the global economy, and there is cause for cautious optimism about the broader implications of this, not least for international progress on environmental sustainability and social planning.

“You can see that the government is jumping on the opportunity for leadership created by the absence of the US in these discussions,” Choy notes, alluding to the Trump presidency. “But for a lot of creative people I talk to in China, it’s not about power and control: they genuinely think that they can share the experiences, knowledge and insights that they have gained from this crazy period of urbanisation to reach out to a global audience, to help everyone.”

Right: Studio 10, Photo Chao Zhang, Beauty and the East, gestalten 2021.

Words Greg Thomas

Beauty and the East is published by Gestalten

Fleeting Moments

Alex Mitchell

Alex Mitchell (b. 1992) is a photographer from Toronto, whose work explores the spectrum of Surrealism using an everyday lens. He transforms the mundane, applying a mix of strategic artificial light, rich colours, and a singular point of focus. Close cropping draws attention to material details. Puddle edges resemble waves lapping the shore, blurring the distinctions between up and down. Non-linear shadows create unexpected textures. Against a variety of seemingly quotidian objects, Mitchell calls upon fantastical colour schemes and skylines, resembling rare and unique sunsets – when the light has further to travel and blue rays scatters before they reach us. Pink and purple atmospheres pull the viewer into phenomenological scenarios, where each moment is unpredictable: ephemeral and temperamental. These images revel in opportunity – in aesthetically stimulating moments – and are presented like snapshots from a lucid dream. instagram.com/alexandormitch.