28 minute read

Moments of Uneasiness

Brooke DiDonato

The first uses of the word “canny” appear in the 1600s in Irish English and Scottish to describe individuals who are knowing, wise, or wary. By the 1800s, the word took on a new definition in northern England as an intensifier, meaning “very” or “considerably.” By 1906, “uncanny” was first used by German psychiatrist Ernst Jentsch in On the Psychology of the Uncanny. The word was referred to in its native German as “unheimlich” (unhomely) pertaining to concepts outside of our understanding or beyond our wider awareness. In 1919, the term was adopted by Sigmund Freud to describe concepts that are both familiar and alien simultaneously. “Unhomely” began to refer to something deep within us – unknown, hidden or repressed emotions. Brooke DiDonato’s work sits within a contemporary reading of The Uncanny in photography: images which are at once unsettling and alluring, set within familiar domestic locations. brookedidonato.com.

, 2020. Courtesy of the artist. Brooke DiDonato, Wake Up Call

2020. Courtesy of the artist. Brooke DiDonato, Everything but the Kitchen Sink,

d, 2019. Courtesy of the artist. Brooke DiDonato, The Weight of a Heavy Min

, 2016. Courtesy of the artist. Brooke DiDonato, Half and Half

, 2018. Courtesy of the artist. Brooke DiDonato, Untitled

, 2020. Courtesy of the artist. , Act Two Brooke DiDonato

Updating the Records

Brazilian Modernist Photography

MOMA DISMANTLES THE NARRATIVE OF PHOTOGRAPHIC HISTORY, FOCUSING ON AN UNDERSTUDIED CHAPTER FROM THE HEART OF SÃO PAULO IN THE MID-20TH CENTURY.

Fotoclubismo: Brazilian Modernist Photography, 1946–1964 is the first major museum exhibition of its kind taking place outside of Brazil. On view at The Museum of Modern Art, New York, from 21 March, the show focuses on the unforgettable creative achievements of São Paulo’s Foto-Cine Clube Bandeirante: a group of amateur photographers widely heralded in Brazil, but essentially unknown to European and North American audiences. Sarah Meister, Photography Curator, expands on the exhibition’s key themes and the controversial history of this pioneering collective.

A: The Foto-Cine Club Bandeirante was established in São Paulo in 1939. How did the group come together?

SM: The founding of the Foto-Cine Clube Bandeirante (FCCB) is a tale rehearsed regularly in the pages of the Boletim, the club’s monthly magazine. A typical account would describe “a small group of idealists” gathering at a photographic materials store in downtown São Paulo. They chose their name because bandeirante “was the name given to the men of São Paulo who explored the backlands of Brazil; for these new Paulistas would be the new bandeirantes [exploring] art photography across Brazil.” Today we recognise how problematic it is to speak in such glowing terms about a group of “standard-bearers” (the literal translation of bandeirante) whose adventurous spirit resulted in the enslavement of Indigenous people, the overwhelming expansion of territory under colonial control and the exploitation of natural resources. Yet the standard FCCB narrative overlooked this reality, aligning their pioneering efforts with these historical figures.

A: Who were the key figures leading the group and how would new members find and approach the collective?

SM: Eduardo Salvatore was president of the FCCB from 1943 until 1990. Salvatore’s formidable leadership qualities arguably eclipsed his artistic talent, but he championed important work amongst peers. He fostered an environment in which competition and criticism encouraged innovation, and he made sure that these achievements were celebrated in Brazil and globally. The club’s reputation – encouraged through annual international salons, the Boletim and considerable attention in the local and international press – made it easy for anyone serious about photography to find one another.

A: What were the key aesthetic or formal qualities heralded by the group? How did the club respond to the history of the medium and envision its future?

SM: In 1951 Salvatore proudly declared: “At FCCB, we are never satisfied with the work we do and always want more; it is progress we are after: new themes, subjects, forms of expression. In fact, we are witnessing a clash between two mindsets: old ‘pictorial’ photography (so called because it imitates static, lifeless, academic painting) and a new, more photographic, more vigorous mentality, replete with life and humanity, bold angles and plays of light, and enjoying the photographic process along with all the characteristics that make it unique and distinctive.” This perspective was not quite as ubiquitous as Salvatore perhaps made it seem, although the 140 photographs in this exhibition (and accompanying book) convincingly capture this sense of spirit and passion.

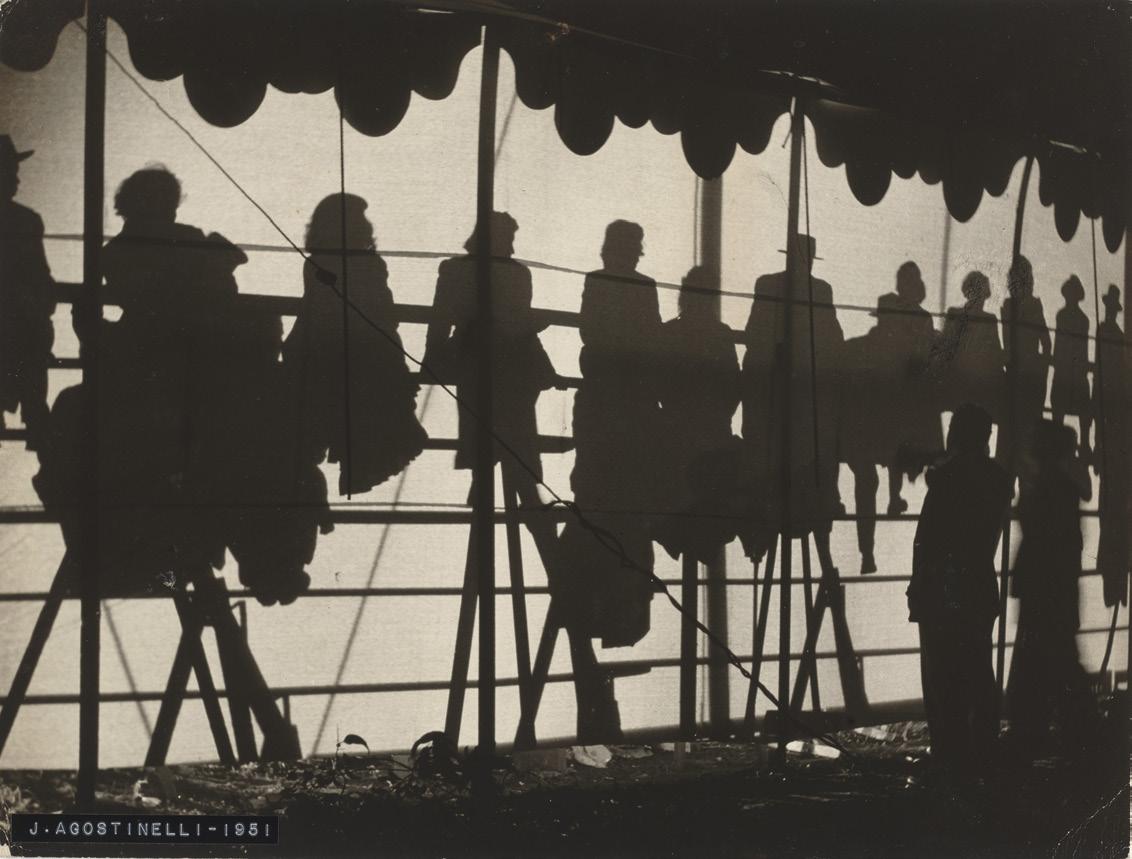

Previous Page: Thomaz Farkas. Ministry of Education (Ministério da Educação) [Rio de Janeiro]. c. 1945. Gelatin silver print, 12 13/16 × 11 3/4 in. (32.6 × 29.9 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of the artist.

Left: Maria Helena Valente da Cruz. The Broken Glass (O vidro partido). c. 1952. Gelatin silver print, 11 7/8 × 11 1/2 in. (30.2 × 29.2 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Acquired through the generosity of Donna Redel. © 2020 Estate of Maria Helena Valente da Cruz.

A: These individuals began working at the beginning of WWII; what were the socio-political contexts of Brazil at this moment? How did this feed into the group’s ideas, and bookend the period presented at MoMA?

SM: The dates that bracket the temporal scope of the exhibition correspond to artistic, political and practical realities in Brazil: 1946 was the year the FCCB first published its Boletim; it was also the year in which a new constitution was adopted and democracy restored, following Gétulio Vargas’ repressive Estado Novo regime. On the other end, 1964 marked the beginning of a brutal military dictatorship that would last more than two decades. By that time, the innovation and creativity associated with amateur photo clubs around the world was already on the wane, and the censorship and repression ushered in by the dictatorship marked the end of an extraordinarily fertile era for photography in Brazil.

A: When was the FCCB's most creative period?

SM: In October 1951 the Boletim references a “new school of art photography,” the beginning of a wildly creative period. By 1955 the term Escola Paulista (Paulista School) appears to have been broadly adopted. In a review of a solo exhibition by Marcel Giró, the Boletim reported: “Giró is undoubtedly one of the leading representatives of this type of photography, which has stood out for its bold angles and compositions, its play of lines, light and shadow.” Although the Escola Paulista is not, by definition, synonymous with the FCCB, there is a perfect overlap between individuals associated with the group and the movement. Alas, almost as soon as FCCB had achieved fame, quotas, import duties and other economic challenges began to take their toll.

A: Who were the photographers most influenced by? Do they cite certain movements or media? How important did the FCCB find artwork made as a cultural response?

SM: The group was keenly attuned to artistic developments across various media and borders. The FCCB's work was displayed prominently in the second São Paulo Art Biennial (1953-1954), and they would regularly invite leading practitioners and critical thinkers – from Waldemar Cordeiro and María Freire to Mário Pedrosa and Walter Zanini – to speak at the club’s headquarters as well as commission, translate and reprint articles from a wide variety of newspapers and magazines, both domestic and international. The cities of São Paulo, Rio de Janeiro and (beginning in 1960) Brasília were filled with buildings by notable architects that were their own source of creative inspiration. Their work resonates convincingly with contemporary achievements in the USA, France, Germany and elsewhere, although I would argue that these were parallel achievements, not influences.

A: When did the collective begin to gain recognition, validating modern Brazilian photography in the eyes of many curators, institutions and countries?

SM: As early as 1946, the FCCB was invited to join the Photographic Society of America (PSA), rightly taking it as a signal of their arrival on the international scene. In May 1950 they were one of two non-European groups invited to become founding members of FIAP (Fédération Internationale de l’Art Photographique). Photographs by members of the FCCB were awarded prizes in amateur salons across six continents. Despite this widespread recognition at the time, their achievements were all but forgotten outside of Brazil, that is, until now.

A: Why do you think these figures have been forgotten or left out of the artistic canon? What critical issues does this raise in terms of representation and recognition in the art world, in the 20th century and beyond?

SM: Perhaps the two greatest biases that affected – and apparently continue to affect – the reception of the work were the twin beliefs held, consciously or not, by the cognoscenti of cultural capitals across western Europe and the USA. The first of these ideas was that art produced in the “peripheral” zones of the globe was necessarily derivative or else hopelessly out of step with the aesthetic discourse of the day. Second was the notion that the amateur, whether in Paris or New York or in “peripheral” cities such as Lagos or São Paulo, was likewise condemned at best to produce convincing simulacra of the advanced art of their time or at worst to traffic in the shopworn, whether clumsily or with uncommon technical finesse. The peripheral and amateur, no matter how accomplished, carried the inescapable musk of the second-rate.

A: This is the first FCCB show outside of Brazil; how does it fit within MoMA's programming and curatorial plans?

SM: From its privileged position in New York, The Museum of Modern Art has long dominated the ways in which the history of modernism is told, a story that has over time been distilled into a neat progression. This narrative is, however, at odds with any close reading of the historical record, and MoMA is now committed to dismantling this widely accepted documentation. This show is an opportunity to highlight extraordinary achievements, and also to reflect on the structural and aesthetic hierarchies that have contributed to their absence from histories of modernism outside of Brazil.

A: How have you brought to light FCCB's key principles?

SM: Both the book and the exhibition present the work of six photographers in depth – Gertrudes Altschul, Geraldo de Barros, Thomaz Farkas, Marcel Giró, German Lorca and José Yalenti – offering audiences an opportunity to appreciate a wide spectrum of achievements. However, to experience the full scope of the club’s vibrant heyday, it is essential to share examples of equally compelling work by dozens of other members who toiled in the same darkroom and submitted their prints to the same salons. The images are organised in groups according to the club’s concursos internos (internal contests), but also with focused presentations of individuals.

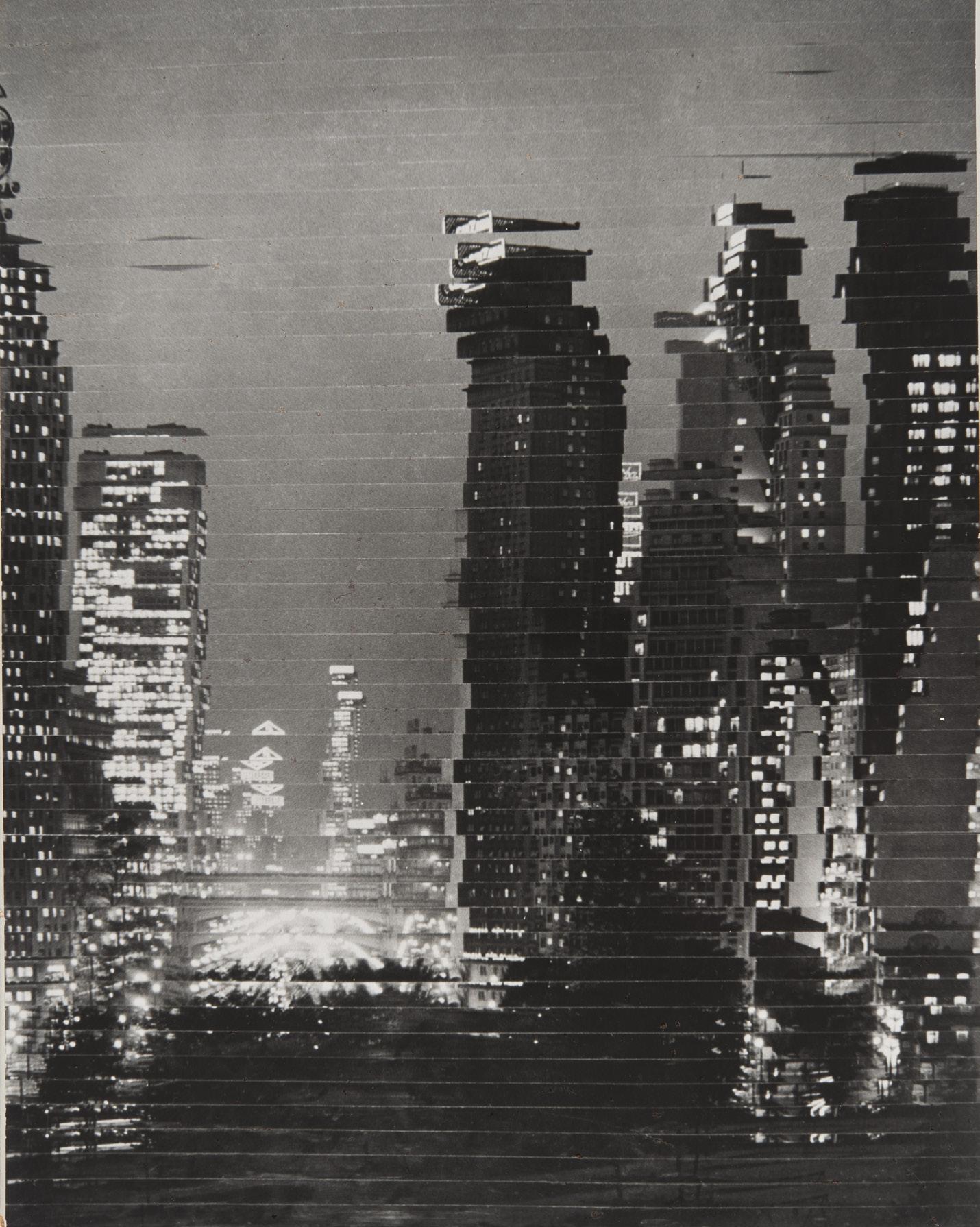

Right: Roberto Yoshida. Skyscrapers (Arranhacéus). 1959. Gelatin silver print, 14 9/16 × 11 9/16 in. (37 × 29.3 cm). Collection Fernanda Feitosa and Heitor Martins. © 2020 Estate of Roberto Yoshida.

A: The FCCB is just one artistic group classed as “amateur” despite pushing multiple boundaries. Photography is now widely accessible; individuals across the globe can shoot and publish work without professional or academic training. How are the goalposts shifting?

SM: The widespread compulsion to articulate and defend what it is that makes a “good” photograph is itself an under-studied thread that connects the artists of the New Yorkbased Photo-Secession (who sought to distinguish their work from the hordes of professionals and Kodak-wielding amateurs at the turn of the 20th century) to the postwar photoclub circuit, and it is close to the heart of MoMA’s history and evolving attempts to define what is worthy of being considered and recognised as “modern art.” The near-complete exclusion of these figures to date, in light of their irrefutable appeal, should also be understood as a critique of this institution’s – and my own – vexed efforts to make sense of the marvellously sprawling, unruly medium of photography. Words Kate Simpson

Fotoclubismo: Brazilian Modernist Photography, 1946–1964 MoMA, New York, 21 March - 19 June

Suspended Moments

The luxury Swiss skincare brand continues its commitment to the arts world with a collaboration between Nobuhiro Nakanishi and Max Richter, at Art Basel Miami OVR.

“Our audacious spirit – a willingness to break the codes of luxury, to follow untrodden paths that surprise as much as they inspire – is the very same audacious spirit as that of the artist," notes Greg Prodromides, Global Chief Marketing Officer at La Prairie. Beyond skincare, the brand has been inextricably linked to the art world from its inception in 1931 in Montreux, Switzerland. La Prairie explores the union of art and science through artistic collaborations presented at international fairs, including Art Basel as well as West Bund Art & Design. They continue to work with visionary creatives from across the globe, from Swiss-Guinean photographer Namsa Leuba and Spanish installation artist Pablo Valbuena to French designer Paul Coudamy and even pioneers from the

Bauhaus school. For Art Basel’s OVR Miami Beach (Virtual edition, 2-6 December 2020), La Prairie commissioned Japanese artist Nobuhiro Nakanishi and British composer Max Richter to explore the realm of timelessness, eternity and dreams.

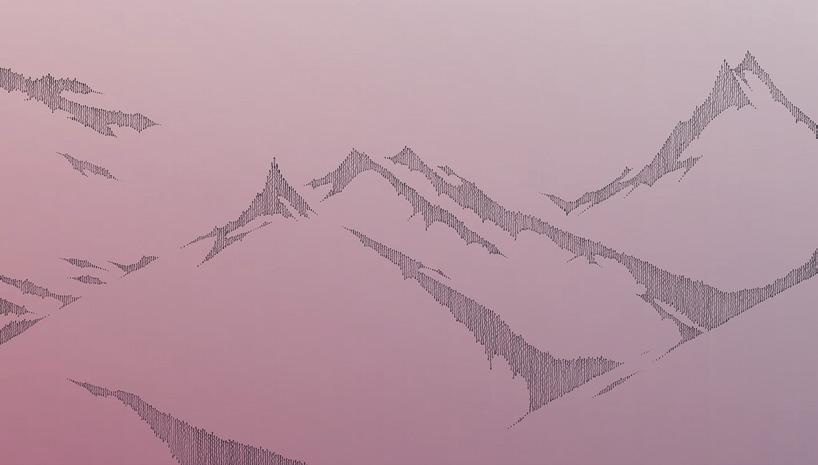

For Eternal Circle, Nakanishi employed a centuries-old Eastern approach to handdrawing that consists of countless vertical lines drawn free-hand by the artist. The resulting piece comprises a 60-piece row of individual stripe drawings. When aligned, the individual pieces total an astounding 24 metres, one for every hour of the day.

Installed in an endless loop, they create an eternal image end-to-end – a flowing representation of past, present and future in which the last drawing of the sequence meets the first and blurs beginning and end into a single, eternal whole. The drawings have been incorporated into a film accompanied by Richter’s Platinum score, complementing the flowing loop of lines with an emotional, soaring rhythm.

This collaboration builds on La Prairie’s commitment to connecting past and present, coming alongside the launch of their latest skincare product, the Platinum Rare HauteRejuvenation Protocol. This addition to the exclusive Platinum Rare Collection confirms La Prairie is as bold scientifically as they are artistically. We speak with Nakanishi Nobuhiro about the artwork, and how he interpreted the open brief.

A: Your artwork moves between installation, sculpture, photography including "stripe drawings" of natural landscapes. How would you describe your practice?

NN: For me, sculpture comprises the relationship between time and body. In nature, for example, the light dynamically changes in the sky with the morning and evening sun. I often climb up mountains to document and depict these changes, physically feeling the terrain. Nature isn’t a uniform and stable landscape, but a space to feel the flow of time through the body. For my practice, I transform nature and space into a continuous mass of time through photography, immersing the viewer away from the chaos of everyday life. I draw a lot of inspiration from the traditional Japanese architecture and gardens, spaces that allow for the human body and eyes to wander and move around. This thinking is rooted in the Japanese Buddhist, who believes the world is not external to the body, but the human is part of the layers that make up the world.

A: How important is it that you create multi-disciplinary work, which exists outside of a singular definition, mirroring ephemeral subject matter and phenomena?

NN: Academic subjects – such as science and history – continue to develop. Art captures things that human beings have not yet systematically understood. Art makes it possible to instinctively grasp things that mankind cannot yet explain. My work is where emotions are heightened, going beyond tangible art.

A: Why is it important that we, as viewers, consumers and individuals, slow down and take time to appreciate a singular moment and become rooted in the present?

NN: For me, there is no boundary between a particular moment and eternity. In my work, one moment overlaps another. In many of my installations, I present images in a loop or circle, transitioning from one second to the next allowing the viewer to see the time flow. For me, time does not move at a constant, linear speed, but changes through the given individual and their line of sight. In the everyday, I see time through the clock face, but in my practice, I want to be freed from this concept of time. I create an imaginative experience linked to an extraordinary, looping universe. 1

2

3

5

7

A: La Prairie’s commission encapsulates the idea of the “Platinum Moment.” What does it mean to you and how did you begin to interpret the brief?

NN: Platinum is a special and rare precious metal – a substance carved from the depths of the universe. When grappling with such a fragment, our imagination is stirred. We begin thinking about the formation of the world, from the origin of creation and beyond the dimensions of what we can physically see.

A: You often visit landscapes primarily – taking photographs before translating these into artworks. How did you respond to the Swiss mountain formations?

NN: Colours, light and clouds might seem far away, but when I stand on the summit, I feel connected within a continuous, borderless space. I think that landscape is a motif I can capture as a negative sculpture of the entire earth. The Swiss mountains impressed me immensely. They are completely different from the Japanese soil-rich land I am used to. Instead, I found rock mountains of hard minerals that have formed after an enormous amount of time. The range stood out sharply on the horizon, and the clouds surrounded them softly, shape-shifting. The huge accumulation of mountains offered an extreme contrast to the usual, fast-paced speed of time in the built-up world. The scenery wasn't just beautiful; I experienced the mystery of being human in our galaxy. Nature makes us feel part of something bigger.

A: Tell us about Eternal Circle, the new work your created?

NN: In my practice, I focus on two types of works: Layer Drawings and Stripe Drawings. The Stripe Drawings comprise numerous vertical freehand drawn lines by pencil on paper. The set of lines – drawn at intervals – adjoin without defining a solid figure. The lines cannot exist without the gaps, and the blank spaces cannot exist without the lines; they co-exist in perfect harmony like two sides of a coin. Eternal Circle is a film that includes 60 drawings and music, combining ancient traditions and craftsmanship with new technology, digitised into video. In the film, the first and last images are connected, drawing from ideas from Japanese picture scrolls.

A: How did you start planning the collaboration with Max Richter?

NN: This is the first time that I have collaborated with a composer. We made the work as a response to my experience in Switzerland and the notion of time inherent to the element of platinum. I was conscious of including soft, subtle transitions in the music and images, replicating what I remembered from the summit. The goal was for Richter's music to depict my experience – where contours, spatial distances and physical boundaries dissolve, leaving a sense of a faraway universe immune to physical touch. More than just a succession of lines, the pencil-drawn lines capture an infinite flow between the artwork and viewer – a bond between representation and reception. This is an endless loop conveying both tactile and eternal beauty.

A: La Prairie is a brand that combines science, heritage and art. How did you and Max tap into these connected concepts, using both traditional and contemporary techniques, whilst observing the alpine landscape?

NN: Before travelling to Switzerland, I had researched the concept of time in outer space and how this notion could relate to a fixed location like Switzerland. My visit to Switzerland was spent shooting the scenery. Afterwards, whilst drawing the topography, I was transported back to the moment, feeling the air on my skin. I then used digital techniques to recreate these experiential images and sensations.

A: How has the pandemic inspired you to work differently; can we see this here?

NN: I have re-acknowledged the communion between the body and its environment. Inspired by an ancestral technique, freehand drawing is completely disconnected from the online world, the same way my mind was disconnected from any time restrictions. Seeing the process of these tranquil drawings gaining motion in a digitised movie felt like travelling. This work is a unique opportunity to think about the relationship between digital tools and the human body.

La Prairie Platinum Rare Haute-Rejuvenation Protocol is available from 15 February. laprairie.com | nobuhironakanishi.com | maxrichtermusic.com

Images: 1. The Platinum Moment: An Artistic Encounter. 2. Platinum Rare Haute-Rejuvenation Protocol. 3. Eternal

Circle by Nobuhiro Nakanishi, 2020. 4. Nobuhiro Nakanishi’s creative journey at the Niederhorn peak. 5. Platinum – a rare and desirable metal. 6. Nobuhiro Nakanishi, Niederhorn Peak in the Swiss Alps. 7. Nobuhiro Nakanishi and Max Richter, An Artistic Encounter for La Prairie. 8. Platinum score by Max Richter at London’s Air Studios.

1Brief & Drenching NAIMA GREEN

New York is the newest outpost for the internationally renowned, Stockholm-based institution Fotografiska. Its ambitious programme responds to ever-changing societal issues, movements and themes in immersive and innovative ways – a welcome addition to the New York photography scene, which is famous for constantly reinventing itself.

No contemporary artist could better represent this new institution than Naima Green. The Brooklyn-based artist and photographer approaches the theme of identity through an incredibly multidisciplinary practice that goes beyond photography to comprise video and furniture. Brief & Drenching complements her solo thesis exhibition at the International Center of Photography last year and includes highlights from her most recent work, somewhere between documentation, multidisciplinary research and stylistic exercises.

At the centre of the exhibition is the Pur·suit series, which features photographs of queer womxn, trans, non-binary and gender-nonconforming individuals – which she also repurposed as a deck of 54 playing cards inspired by Catherine Opie’s Dyke Deck (1995). Green photographed over 100 sitters in nine days, resulting in stunning portraits through which tradition is transformed and reimagined.

Selections from the Two Pictures series are also included and wonderfully showcase Green’s unique talent in showing proximity and intimacy with her subjects. She approaches photography as “an actual organism that evolves when people evolve.” The work reveals a commitment to inclusivity and accessibility, making the artist, subject and viewer equal entities. It may not be easy to purge photography of its intrinsic objectification, but Naima Green is willing to try. Words Louis Soulard

Fotografiska, New York 28 August - 28 February

fotografiska.com

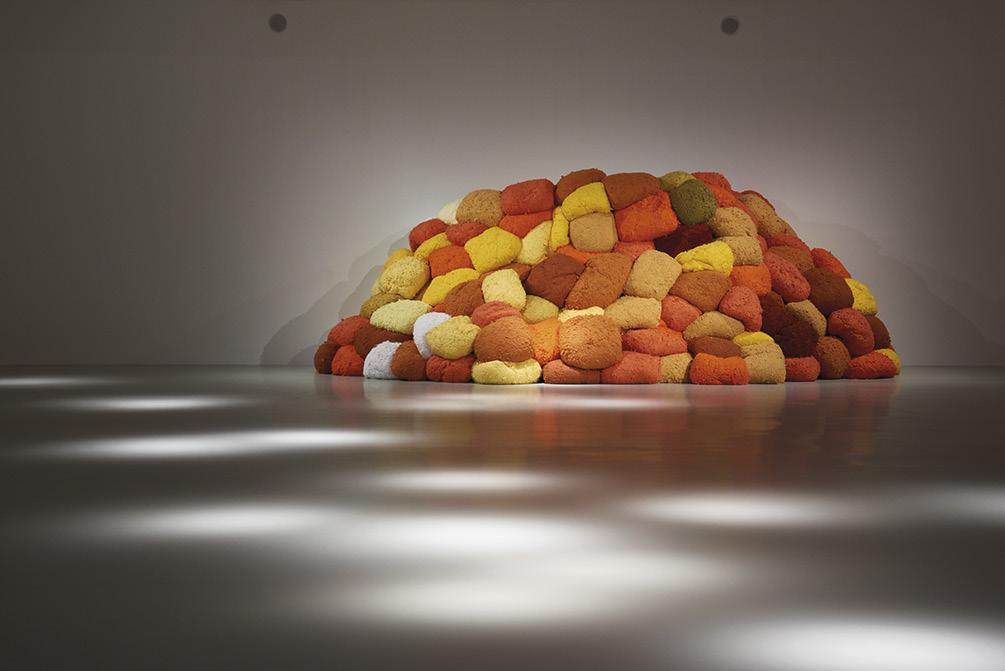

2Thread, Trees, River SHEILA HICKS

Sheila Hicks (b. 1934) is not only one of the most renowned living artists, but also one of the most universally loved: a sweetheart of the curators, critics and collectors, with innumerable museum shows over the last 50 years. Interpretation of her signature large-scale textile sculptures often oscillates between feminism and craftsmanship. Some radical curators stress that she has elevated the textile production – traditionally associated with domestic women – to the rank of high art, whilst more conservative ones pay attention to the elements of “craftsmanship” which are central to Hicks' artwork.

However, Thread, Trees, River seems to have found a way out of this limiting dichotomy. By giving more space to lesser-known artworks alongside ancient artefacts from the museum’s permanent collection, curator Bärbel Vischer has reinterpreted Hicks as an artist entirely consumed by history.

Three spacious rooms – out of the four dedicated to Hicks – showcase dozens of textile fragments almost undistinguishable from Medieval tapestry. Hicks’ footprints on linen remind us of Catholic relics, whilst knitted panneaux are reminiscent of Pharaonic mural paintings. Elsewhere, a carpet depicts the images of gates – think of Babylon’s Ishtar Gate or the Lion Gate in Mycenae. These artworks “cast shadow” on Hicks’ bright, abstract installations displayed in the central exhibition space – so much so that these periphery pieces seem as though they belong to a different artist altogether.

Vischer tells the story of two artists living in the same body. Although this radical reading of Hicks’ heritage, style and identity cannot change the decades-old theoretical consensus, for now – at least – we have a dissenting voice and a new reading of her work through the Museum of Applied Arts. Words Nikita Dmitriev

MAK – Museum of Applied Arts, Vienna 9 December - 18 April

mak.at

3Girlhood MARY ELLEN MARK

Living on the fringes invites anonymity. However, Mary Ellen Mark (1940-2015) gave a name to the countless outcasts she photographed during an expansive 50-year career.

Images culled from a donation of 160 prints by the Photography Buyers Syndicate to NMWA focus on girls and young women. They range from early 1960s work in Turkey to Polaroid photographs from the 2000s. Mark grasped our shared humanity by focusing on people who were “away from mainstream society and toward its more interesting, often troubled fringes.” It’s an affinity she shared with photographers like Eugene Richards and Diane Arbus, though the latter took a much harder turn in that direction.

But the comparisons stop there. Where Arbus’ square prints are directly confrontational but distant, Mark sought an emotional connection with subjects that made the figures more relatable. Documenting a maximum security section of a mental institution – found whilst photographing on the set of One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest (1975) – Mark produced images like Laurie in the Bathtub, Ward 81, Oregon State Hospital, Salem, Oregon (1976). A woman considered dangerous to herself and others here appears disarmingly naïve and youthful, but also otherworldly, only her head and wet hair peering out from a suds-filled bath.

From the start of Life magazine’s “Streetwise” project documenting children living on Seattle’s mean streets in 1983, Mark developed a lasting bond with Erin “Tiny” Blackwell. Mark’s portraits of Tiny follow her journey from teen sex worker to a mother of 10 children, with periods of addiction, recovery and marriage along the way. These are images of hardship and despair, but also levity. Words Olivia Hampton

NMWA, Washington DC 3 March - 11 July

2a 1

2b

5a

6

4Broken Nature COLLABORATION WITH TRIENNALE DI MILANO

Broken Nature was originally organised in 2019 as the main group exhibition of Triennale di Milano’s 22nd edition. The exhibition includes new and innovative work that speaks to the designer’s role in creating sustainable objects and products, comprising a variety of media and materials, many of which have been recycled or otherwise repurposed,

Highlights include microalgae and sugar-based biopolymer drinkware by Atelier Luma – a project which explores the potential of growing micro and macro biomaterials. Meanwhile, charcoal bowls, cups and plates by Kosuke Araki are the result of two years of work during which Araki collected inedible leftovers, such as vegetable scraps, eggshells and bones, and burned them to create moulds.

Perhaps one of the most impressive installations in the exhibition is Alex Goad’s MARS – Modular Artificial Reef Structure (2013). This large-scale module is a lattice system made using 3D-printed resin moulds that are then cast in ceramic. Before being submerged underwater, coral fragments are attached to the structures. MARS provides a rigid skeleton on which transplanted corals can grow, and its complex geometry acts as a protective habitat for a number of reef species.

Though it is focused on design, the show also features additional and highly relevant material, which includes photographs by NASA as well as architectural research projects by Mustafa Faruki, founder of theLab-lab. MoMA offers powerful insights into the ability of contemporary design to respond to key issues surrounding the climate crisis – global heating, acidification, pollution, desertification and species extinction. Works on view further highlight the shared, symbiotic relationships that exist amongst designers, engineers, artists and scientists, and the ways in which these communities continuously collaborate and influence one another. Words Louis Soulard

MoMA, New York 21 November - 15 August

moma.org

5Daniel Buren and Philippe Parreno IN-SITU COLLABORATION

For the inauguration of a new gallery in the sixth arrondissement, Galerie Kamel Mennour offers a free museum-like collaboration between two of French conceptual art’s well-established stars: Daniel Buren (b. 1938) and Philippe Parreno (b. 1964). All museums are closed in Paris right now, so this show is a glittering gift – one that should be celebrated and visited where possible. Find respite in this in-situ installation.

Daniel Buren – known for the iconic Les Deux Plateaux at the Palais-Royal and his child-like cubic installations – provides a somewhat Alice-in-Wonderland chamber of mirrorstriped columns and water panels. Walking through the gallery, a sliced version of the viewer disappears and reappears in unexpected places thanks to mirror reflections at opposite sides of the space. Doppelgängers suddenly appear in rooms you’re not even in – a delightfully playful effect.

Meanwhile, Philippe Parreno – who made his reputation in video art, text, performance and drawing – leaves traditional media by the wayside in favour of more high-concept, high-tech art here. However, Parreno always tries to work with in-situ pieces; his installations tend to be site-specific and this current collaboration is no exception. Panels of coloured lights, installed around Buren’s mirrored columns, are constantly dimmed and reignited by a series of touchsensitive shutters directly connected to sensors that capture the movement of the waves in the nearby Seine. Parreno once said in an interview that exhibitions are “like taking a breath” – and that is completely true here. The triggering of the shutters reminds viewers of a pair of inhaling lungs drawing breath in this immersive, almost underwater installation.

Featuring fragmented glimpses of your own body, the constantly varying shutters create an almost bewildering visual and sonic atmosphere. Polyphony is the word that comes to mind: it’s like walking through a conceptual orchestra playing on the colours in your memory and imagination. Words Erik Martiny

Kamel Mennour, Paris 5 December - 27 February

kamelmennour.com

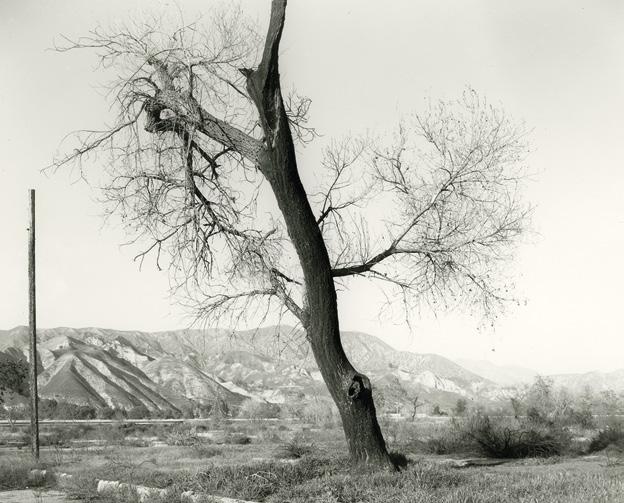

6Los Angeles: Landscapes of Four Ecologies MARK RUWEDEL

Mark Ruwedel (b. 1954) cares little for LA’s brochurefriendly vistas or its moniker, the City of Angels. More hell or high water, Landscapes of Four Ecologies captures the tragic beauty of a landscaped scarred by warring elements. The exhibition draws from in-progress work funded by the Guggenheim Fellowship since 2014, comprising multiple series of striking black and white photographs.

In the Burnt Trees series, Californian wildfires scorch the earth and turn bark to charcoal. Looking towards to the Pacific, Sunken Cities offer little solace. High-contrast images of cliffs off the LA coast give way vertiginously to dust and rubble. The giant ash-like sculptures of Verdugo Mountains Fire appear equally inhospitable, off-world, even alien.

Opposite them is the more pedestrian Earthworks Portfolio. Excavations and floodlit plains – commercial spaces – mark human activity which is elsewhere dwarfed or muscled out of shot by the sheer scale of a (post-)apocalyptic landscape. It’s easy to miss the slither of road in Sepulveda Pass Fire #1, 2018. Squint and a dot becomes a hiker.

Ruwedel’s photography condemns us to the Anthropocene epoch. It’s clear who shoulders the blame and fallout of the climate catastrophe. The artist’s hand-printing of the silver gelatin images gives them a tactile, historical quality, jaundiced in colour, similar to the early American photography of Carleton E. Watkins and Timothy H. O’Sullivan in the 19th century. The prints exacerbate the exposure in Burnt Trees expressly, lending a melancholic tone to the blanched leaves which disappear against the sky. We begin to ask: is this a vision of our future or a historical reality today?

Overall, Landscapes of Four Ecologies excels in its geometric, categorical approach to framing. The claustrophobic crops – of mountains and trees in particular – have audiences searching for symbols in the roots and fractals of the branches. Some trunks are cruciform, others unyielding. Words Jack Solloway

Large Glass, London 11 December - 19 February