YOU ONLY GET ONE SPIN

Tick tock, tick tock, tick tock goes the clock. It’s so rhythmic it’s almost soothing. It lulls you into a false sense of security. Tick another coffee. Tock another meeting. Tick another lunch. Tock another quiet night in.

And before you know it, you’re so numb from the comfort of routine that you didn’t feel a thing when that great adventure called life slipped away like sand between your fingers.

But fear not, adventure has other plans. Roll with them. Embrace adventure. Grasp it with both hands until your knuckles turn pale. Don’t let comfort take you down. Rise above routine and monotony. Ride shotgun with fear and the unknown. Don the uniform of the restless. Get uncomfortable being comfortable.

And here’s the reward for the discomfort. Your heart will be fuller, your compassion deeper, your horizons wider and your memoir way, way, better. Before you die, make sure you have lived.

And never forget, you only get one spin.

Architect. Mentor. Beekeeper. A life well planned allows you to

While you may not be running an architectural firm, tending hives of honeybees and mentoring a teenager—your life is just as unique. Backed by sophisticated resources and a team of specialists in every field, a Raymond James financial advisor can help you plan for the dreams you have, the way you care for those you love and how you choose to give back. So you can live your life.

© 2020 Raymond James & Associates, Inc., member New York Stock Exchange/SIPC. Raymond James Financial Services, Inc., member FINRA/SIPC. Raymond James® and LIFE WELL PLANNED® are registered trademarks of Raymond James Financial, Inc.

© 2020 Raymond James & Associates, Inc., member New York Stock Exchange/SIPC. Raymond James Financial Services, Inc., member FINRA/SIPC. Raymond James® and LIFE WELL PLANNED® are registered trademarks of Raymond James Financial, Inc.

60 HIGHER GROUND

Amid the serene farming villages and monasteries of China’s Yunnan province, writer Peggy Orenstein discovers a slice of paradise.

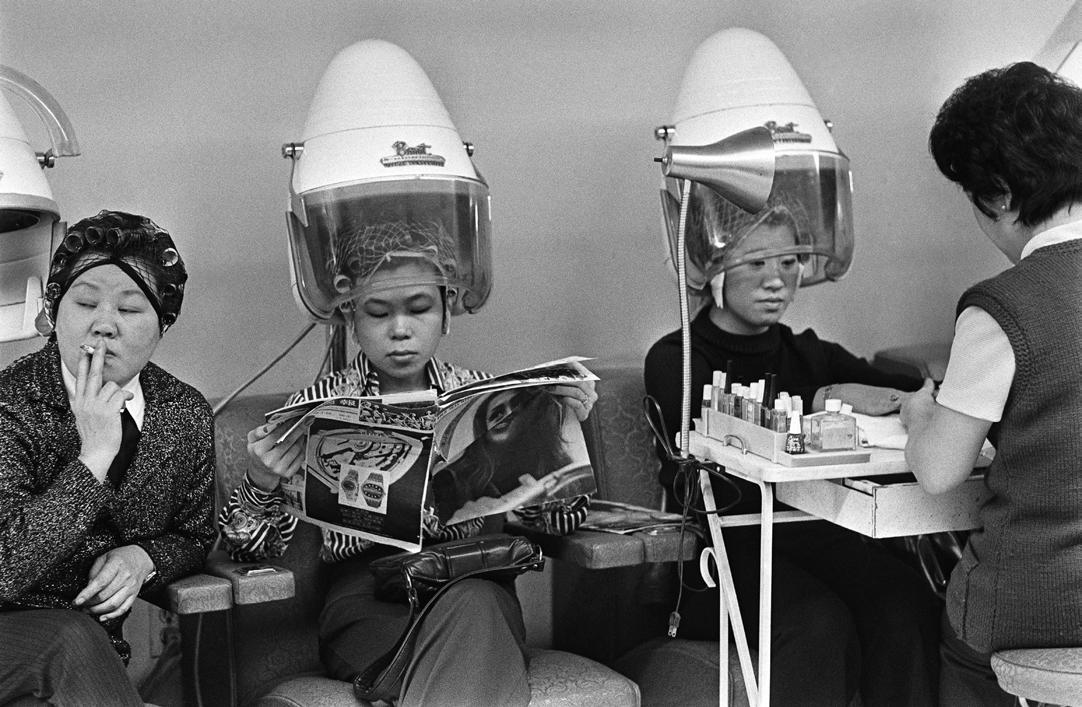

72 PERSIST A photographic love letter to New York City

84

TUSCANY BY THE BOOK

On a dream trip to Dante’s birthplace, a bibliophile meets the folks keeping the art of book-making alive.

My hope was to find something less scripted and more true: the bliss and grace of the unexpected

EDITORIAL

VP, EDITOR IN CHIEF Julia Cosgrove @juliacosgrove

EXECUTIVE EDITOR Jeremy Saum @jsaum

CREATIVE DIRECTOR Supriya Kalidas @supriyakalidas

DIRECTOR OF DIGITAL CONTENT

Laura Dannen Redman @laura_redman

DIRECTOR OF PHOTOGRAPHY Tara Guertin @lostluggage

DEPUTY EDITOR Jennifer Flowers @jenniferleeflowers

MANAGING EDITOR Nicole Antonio @designated_wingit_time

SENIOR EDITORS

Tim Chester @timchester

Aislyn Greene @aislynj

DIGITAL FEATURES EDITOR Katherine LaGrave @kjlagrave

GUIDES EDITOR Natalie Beauregard @nataliebeauregard

TRAVEL NEWS EDITOR Michelle Baran @michellehallbaran

DESTINATION NEWS EDITOR Lyndsey Matthews @lyndsey_matthews

AFAR ADVISOR EDITOR Annie Fitzsimmons @anniefitzsimmons

JUNIOR DESIGNER Elizabeth See @ellsbeths

VIDEO EDITOR Claudia Cardia @chlaupin

DIGITAL PHOTO EDITOR Lyn Horst @laurella67

ASSOCIATE PHOTO EDITOR Rachel McCord @rachelmc_cord

ASSOCIATE EDITORS

Sara Button @saramelanie14

Maggie Fuller @goneofftrack

ASSISTANT EDITOR Sarah Buder @sarahbuder

CONTRIBUTING WRITERS

Lisa Abend @lisaabend, Chris Colin @chriscolin3000, Emma John @foggymountaingal, Ryan Knighton, Peggy Orenstein @pjorenstein, Anya von Bremzen

COPY EDITOR Elizabeth Bell

PROOFREADER Pat Tompkins

FOUNDERS GREG SULLIVAN & JOE DIAZ

SALES & MARKETING

VP, PUBLISHER Bryan Kinkade @bkinkade001, bryan@afar.com, 646-873-6136 VP, MARKETING Maggie Gould Markey @maggiemarkey, maggie@afar.com

SALES

EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR, BRAND PARTNERSHIPS

Onnalee MacDonald, @onnaleeafar, onnalee@afar.com, 310-779-5648

EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR, CARIBBEAN Barry Brown barry@afar.com, 646-430-9881

DIRECTOR, WEST CJ Close @close.cj, cjclose@afar.com, 310-701-8977

LUXURY SALES MANAGER Laney Boland @laneybeauxland lboland@afar.com, 646-525-4035

SALES, SOUTHEAST Colleen Schoch Morell colleen@afar.com, 561-586-6671

SALES, SOUTHWEST Lewis Stafford Company lewisstafford@afar.com, 972-960-2889

SALES, MEXICO AND LATIN AMERICA

Jorge Ascencio, jorge@afar.com

MARKETING & CREATIVE SERVICES

EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR, MARKETING AND SPECIAL PROJECTS

Katie Galeotti @heavenk

BRANDED & SPONSORED CONTENT DIRECTOR

Ami Kealoha @amikealoha

DIRECTOR OF AD OPERATIONS Donna Delmas @donnadinnyc

SENIOR DESIGNER Christopher Udemezue

SENIOR INTEGRATED MARKETING MANAGERS

Sveva Marcangeli @svadore

Irene Wang @irenew0201

MARKETING COORDINATOR

Lindsey Green @lindseygreenlikethecolor

AFAR MEDIA LLC

CHIEF EXECUTIVE OFFICER Greg Sullivan @gregsul

VP, COFOUNDER Joe Diaz @joediazafar

VP, CHIEF OPERATING OFFICER Laura Simkins

DIRECTOR OF FINANCE Julia Rosenbaum @juliarosenbaum21

HUMAN RESOURCES DIRECTOR Breanna Rhoades @breannarhoades

DIRECTOR OF PRODUCT Anique Halliday @aniquehalliday

AUDIENCE DEVELOPMENT DIRECTOR Anni Cuccinello

SOCIAL MEDIA MANAGER Rosalie Tinelli @rosalietinelli

SEO SPECIALIST Jessie Beck @beatnomad

EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR, PROCIRC Sally Murphy

ASSOCIATE CONSUMER MARKETING DIRECTOR, PROCIRC Tom Pesik

OPERATIONS ACCOUNT MANAGER Adam Bassano

PREMEDIA ACCOUNT MANAGER Isabelle Rios

PRODUCTION MANAGER Mandy Wynne

ADVISORS

Priscilla Alexander, Pat Lafferty, Josh Steinitz

NEW YORK OFFICE 28 West 44th Street, Suite 600 New York, NY 10036 646-430-9888

SAN FRANCISCO OFFICE P.O. Box 458 San Francisco, CA 94104-0458

SUBSCRIPTION INQUIRIES

afar.com/service

888-403-9001 (toll free)

From outside the United States, call 515-248-7680

22 Napier Lane, San Francisco, CA 94133. 12. Tax status: Has Not Changed During Preceding 12 Months. 13. Publisher title: AFAR. 14. Issue date for circulation data below: M/J ’20. 15. The extent and nature of circulation: A. Total number of copies printed (Net press run). Average number of copies each issue during preceding 12 months: 301,577. Actual number of copies of single issue published nearest to filing date: 299,001. B. Paid/requested circulation. 1. Mailed outside-county paid subscriptions/requested. Average number of copies each issue during the preceding

No other place in Alaska brings together glaciers, iconic wildlife, panoramic views and the comforts of a city.

Portage Pass

Portage Pass

So, you’ve been thinking about places you might go. Musing on magnificent coastlines with white sands and clear waters. Make sure Lord Howe Island is high on that list. This World Heritage-listed isle is pure paradise at any time of the year, and with just 400 visitors allowed at any one time, you’ll have all its natural wonders to yourself. Take a moment to plan and map out your dream vacation, because when it’s time to fly, we’ll be ready to welcome you back.

It’s time to be inspired, visit SYDNEY.COM

AFAR TRAVELERS’ AWARDS

BEACH HOTEL

Dorado Beach, A Ritz-Carlton Reserve, Puerto Rico

DESIGN HOTEL

Royal Mansour, Marrakech, Morocco

GRANDE DAME HOTEL

The Ritz Paris

EPIC STAY

Four Seasons Resort, Bora Bora

WELLNESS HOTEL

JW Marriott

Scottsdale

Camelback Inn

Resort & Spa

INTERNATIONAL HOTEL

Park Hyatt Tokyo

U.S. HOTEL

Fairmont

San Francisco

FOOD & WINE EXPERIENCE

Blackberry Farm, Tennessee

Where are you dreaming of going this year? AFAR readers cast more than 150,000 votes to honor their favorite hotels, cruises, airlines, trips, anddestinations.Wehopethis comprehensive list of winners helps spark your wanderlust and inspire your next trip. For more details, visit afar.com.

LARGE-SHIP CRUISE

Royal Caribbean MEDIUM-SHIP CRUISE

Seabourn

SMALL-SHIP CRUISE

Windstar Cruises

FOOD & BEVERAGE PROGRAM

Oceania Cruises

EXPERIENTIAL ITINERARIES

Seabourn

ALASKA CRUISE

Holland

America Line

RIVER CRUISE

Viking Cruises

FRENCH POLYNESIA CRUISE

Paul Gauguin Cruises

EXPEDITION CRUISE

Lindblad Expeditions

MEDITERRANEAN CRUISE

Viking Cruises

CARIBBEAN CRUISE

Viking Cruises

Inspirational Paths � Discovery Await

AWAKEKEN N I INNSSPIRAATTION N W WIITH THE WONNDDERS OF G GREREECE.

At Azamara® our signature Destination Immersion® experiences go beyond the realm of cruising in ways that transform even the most seasoned travelers. We connect adventurous spirits with people and cultures through immersive itineraries, longer stays, and more overnights in harder-to-reach ports. We have pioneered the concept of Country-IntensiveSM Voyages— itineraries that include the most iconic destinations as well as hidden gems, all within a single country. There’s no doubt our new Greece Intensive itineraries will reawaken your senses and fill you with wonder. We invite you to view the world with fresh perspective, awaken inspiration, and bring your boutique hotel with you every step of the way.

For more information, call 1.855.AZAMARA, contact your Travel Advisor, or visit Azamara.com. Explore FurtherSM

Santorini, Greece

Santorini, Greece

CULINARY ADVENTURES

Country Walkers

OVER-THE-TOP JOURNEYS

TCS World Travel

TRIPS THAT DO GOOD REI Adventures

RAFTING & KAYAKING TRIPS

Sea Kayak Adventures

AIR TRAVEL

FIRST-CLASS EXPERIENCE

Emirates

U.S. AIRLINE

Delta Air Lines

INTERNATIONAL AIRPORT

Singapore Changi Airport

BUSINESS-CLASS EXPERIENCE

Emirates

INTERNATIONAL AIRLINE

Emirates

U.S. AIRPORT

San Francisco

International Airport

ECONOMY EXPERIENCE

Lufthansa

DOMESTIC REWARDS PROGRAM

Southwest Airlines

FOOD & BEVERAGE PROGRAM

Singapore Airlines

WILDLIFE TRIPS

Wilderness Travel

HIKING & WALKING TRIPS

Wilderness Travel

BICYCLING TOURS

VBT Bicycling Vacations

PHOTOGRAPHY EXPEDITIONS

National Geographic Expeditions

CULTURAL TRIPS

Abercrombie & Kent

DESTINATIONS

EUROPEAN CITY

Paris

ASIAN CITY

Tokyo

NORTH AMERICAN CITY

New York City

SOUTH AMERICAN CITY

Buenos Aires

CARIBBEAN ISLAND

Puerto Rico

AFRICAN CITY

Cape Town

MIDDLE EASTERN CITY

FOOD & WINE DESTINATION

Napa Valley, California

ART & CULTURE CITY

Paris

UNESCO WORLD HERITAGE SITE

Machu Picchu, Peru

WELLNESS DESTINATION

Bali

ADVENTURE DESTINATION

New Zealand

Dubai

OCEANIA DESTINATION

Sydney

SKI DESTINATION

Colorado

U.S. ROAD TRIP

California

Highway One

We Protect This

The Surfrider Foundation is dedicated to the protection and enjoyment of the world’s ocean, waves and beaches, for all people, through a powerful activist network.

To learn more and get involved, visit go.surfrider.org/afar

Founder’s Note

THE COVID-19 PANDEMIC has caused so much pain and destruction. My heart goes out to everyone who has lost a loved one and to those who have suffered through sickness and confinement. And I feel such empathy for those who have had their livelihoods upended and dealt with financial hardship. Our industry, the travel industry, has been crushed, and the consequences have affected so many of our friends and colleagues. It is heartbreaking. AFAR has not been immune. While we greatly expanded our digital content in 2020, this is the first print issue we have published since last spring.

We are fully aware that the pandemic is not behind us yet. In this issue we aim to inspire you to travel when the time is right for you—turntopage37forideasfrom some of our favorite writers.

We also know that we can do better, both as an industry and as travelers. As we begin to reimagine travel, AFAR has joined an industry effort called the Future of Tourism, which is dedicated to inspiring and educating travel businesses and travelers alike to improve what we were doing before the pandemic.

We have always believed that travel can be a powerful force for good in the world. Done right, travel can redistribute wealth; broaden people’s perspectives and make them wiser and more caring;andsupportpeoplewhohavebeenshortchangedbyprejudice

and systemic barriers. And it can do all this while leaving a lighter environmental footprint. To us, the future of travel is one in which local businesses and residents welcome visitors who seek to give, not just take, when they experience a destination. “Our presence changes a place,” writes Eric Weiner on page 20. “The question is how.”

At AFAR, we’ve long said that our readers are the world’s best travelers because we’re a company driven by values, and you respond to those values. You care. You want to make a positive difference. You want to do better.

Based on the way people throughout the world responded to the pandemic, I’m hopeful that there are many more people like you out there. You are the role models who influence how others travel. We at AFAR will do our utmost to help people to be better travelers and more conscientious world citizens. And we ask you to continue to push yourselves to be better travelers. What you do makes a difference.

Together, we can make travel a much more positive force in the world. We look forward to making the journey with you.

Safe

travels, GREG SULLIVAN Cofounder & CEOTo us, the future of travel is one in which local businesses and residents welcome visitors who seek to give, not just take, when they experience a destination.

TRAVEL CAN BE BETTER THAN IT WAS.WE CAN DO MORE THAN SNAP

A PHOTO AND LEAVE.WE CAN SLOW DOWN, TAKE THE TIME TO BE RESPECTFUL,TO APPRECIATE, TO LEARN, AND TO EXPERIENCE THE WORLD MORE DEEPLY.

NEW

THE TRAVELER S MANIFESTO

II will travel again. That much I know. The question is how. I don’t mean whether I’ll be wearing a mask or carrying hand sanitizer— I will be—but a bigger, more philosophical how, and its close cousin, why.

These are questions I thought I had answered. I’ve spent a lifetime traveling and thinking and thinking about traveling. Along the way, I cobbled together my own “philosophy of travel.” Go solo, do no harm, see as much as possible. It was a good philosophy, I thought, one that enabled me to travel ethically while still enjoying myself. But a backlash was brewing, as the scourge of overtourism came into sharp relief. Crowds of eager travelers were sullying the environment and fraying the social fabric of overrun destinations. Friends, meanwhile, questioned my outsize carbon footprint. In Sweden, they invented the word flygskam, “flight shame,” to describe this phenomenon and a hashtag, #jagstannarpåmarken

(#stayontheground), for its remedy. The Dutch airline KLM launched a “Fly Responsibly” campaign, which sounds awfully close to “Drink Responsibly.” Was travel, I wondered, the new alcohol? Or worse, the new smoking?

No, I told myself. Whatever toll my journeying took on the planet was more than compensated for by the good accrued. But the truth is: I never stopped to fully define this alleged “good.” I was winging it. I secretly began to suspect that my friends, and the Swedes, might be right. Maybe travel was the new smoking, and I was a two-pack-a-day guy.

Then came COVID-19, upending the world and shining a harsh light on global wanderers like me. When it became clear it was international travel that enabled the coronavirus to spread so rapidly, I realized how incomplete, how inadequate, my philosophy was. I needed to dive deeper into the how and the why of travel.

Locked down for much of 2020, I had plenty of time to think about past travels, naturally,

but also future journeys. What will they look like? What fresh attitude will I bring to them? I devised a few new principles, refined a couple of existing ones, and stitched them together into a kind of Travel Manifesto. “Manifesto,” I realize, is a strong word. It suggests boldness and daring— revolution, even. This is precisely what I need, what we need: a new way of traveling.

I can’t guarantee I will adhere to my Travel Manifesto religiously, but this is what I aspire to, and aspirations matter. We may miss the mark, but at least we know what we’ve missed and by how much. Then we dust ourselves off and try again.

TRAVEL SELECTIVELY

I CAN’T GO EVERYWHERE. There, I said it. I feel better already. By trying to see everything, I run the risk of seeing nothing. If I’ve learned anything during this time away from travel, it’s that it’s better to travel well than to be

To know the essential Charleston is to understand more than exquisite architecture, transcendent hotels, and revered restaurants. To truly experience Charleston requires time to discover a region that has navigated pain and prosperity, heartbreak and hope to achieve bold progress and realize a more powerful sense of place. The journey continues today.

In telling the full story and encouraging dialogue we cultivate a deeper understanding of the past, advance reconciliation, and develop a stronger community for current and future generations.

Plantations across the Charleston area inspire discussion and education around our community's past by telling the true story of our historic sites and the people - free and enslaved - who were instrumental in defining the region and nation.

Learn about African and African American experiences and contributions to the area's cultural heritage at africanamericancharleston.com. Content on this site, Voices: Stories of Change, spans from pre-Colonial times and beyond.

Create a new connection with history and discover transformative experiences found only in the Charleston area.

MAGNOLIA PLANTATION AND ITS GARDENS

Examine the challenges facing African American families from pre-Colonial times through the modern Civil Rights era through the award-winning program From Slavery to Freedom: The Magnolia Cabin Project Tour.

MIDDLETON PLACE

View the award-winning documentary, Beyond the Fields, or join a special tour originating from Eliza’s House to reveal essential stories about the labor, religion and spirituality of the people who indelibly shaped Charleston’s past.

MCLEOD PLANTATION

Visit the masterfully-restored property and discover the plantation’s strategic significance during the Civil War, including the role of the freed black Massachusetts 55th Volunteer Infantry in emancipation.

DRAYTON HALL

Gain insight into how enslaved workers literally and figuratively built the Lowcountry through Port to Plantation, an interactive exploration of the economic ramifications of slavery in the 18th and 19th centuries.

BOONE HALL PLANTATION

Attend a performance of Exploring the Gullah Culture, a live educational presentation of a unique African American culture that has defined the Lowcountry for more than 200 years.

well traveled. Better to experience places than collect them. When we collect places, we’re in “getting” mode. When we experience them, we’re in “being” mode. And that’s when we create the memories that last.

Going forward, I will triage my trips, careful not to confuse the popular with the good. Popular places are, by definition, over-traveled. There’s something to be said for scruffy places, frumpy places, even boring places. Perhaps there are no boring places, only boring travelers. As I dream about, and plan, future travels, I won’t necessarily skip the Istanbuls and the Tokyos, but I’ll be sure to include the Izmirs and Okinawas.

I was recently inspired by a friend who insists on eating only “quality calories.” Not necessarily calories high in protein or low in sugar, but calories they will enjoy fully. Every journey comes at a financial cost, an environmental cost, and a social cost. Before booking that flight, I will now ask myself: Is the cost worth it? Are these quality miles? I’ll find the answer not on a spreadsheet but in my heart.

ambitious. We can’t all save the world or the dolphins or anything else. But we all can travel for good.

That “good” can take many forms: It could be as simple as supporting Black-owned businesses in a new city or as all-encompassing as a collaborative expedition with climate scientists.

High on my list in this new world: Helping biologists gather data in the Serengeti. Less important than the particulars is a fundamental shift in attitude, from getting to giving.

Might all this purposing get messy? Sure. But travel has always been messy. The notion of the phantom traveler, traversing a place without leaving a mark, is a myth. Our presence changes a place. The question is how. Do we leave it better than we found it or worse?

TRAVEL SLOWLY

SPEED IS THE ENEMY OF TRAVEL, because, as the French philosopher Simone Weil observed, speed is the enemy of attention. Of all the indecencies she witnessed on the factory fl ors of 1930s France, the greatest, she said, was the violation of the workers’ attention. The conveyor belt moved at a velocity incompatible with any other kind of attention, “since it drains the soul of all save a preoccupation with speed.”

Good travel is slow travel. Loiter. Linger. Find a café in Amsterdam or La Paz and plant yourself there for longer than seems normal. I guarantee you will see or hear or feel something you would have missed otherwise.

Variety may be the spice of life, but familiarity is its main course. Even before the pandemic, I found myself less interested in traveling to new destinations than in returning to old, familiar ones, and seeing them anew, through slow eyes.

TRAVEL PURPOSEFULLY

TRAVELING FOR LEISURE is a relatively recent phenomenon. For most of human history, people traveled to flee a war (or to start one), to seek God or treasure, to chart new sea routes, or to explore new wonders. It’s time we turn to purpose-driven travel, especially now that the pandemic has laid bare the hidden (and notso-hidden) costs of tourism.

When we take a vacation, in a way we vacate ourselves. When we travel with purpose— even if that purpose is as simple as traveling with an open mind and a kind heart—we fill ourselves, and, ideally, consider our impact on a destination. Our purpose needn’t be overly

Each autumn, I travel to Kathmandu, plant myself by an old Buddhist stupa called Boudhanath, and watch the collage of people and commerce circling it. At first, I notice the small differences: a posh new café and a sign warning that “the use of drones is strictly prohibited.” Plenty about Boudhanath hasn’t changed, though. There are the Buddhist pilgrims circling the stupa at all hours, twirling metal prayer wheels, and there’s the young Tibetan woman selling oil lamps and sandalwood beads. The only reason I notice any of this is because I slowed down.

As a rule, I estimate how long I should reasonably spend in a place— then add 20 percent. I’ve never regretted the extra time. A while back, I was planning on spending two weeks in Reykjavík, the Icelandic capital, but decided to tack on three additional days. It was during those three days that I met the two most memorable characters of my journey: a perceptive composer named Hilmar, who taught me the importance of “cherishing your melancholia,” and a smitten expatriate named Jared.

Now, after the forced stillness of quarantine, I’ve learned that my capacity for slowness is greater than I thought. I’m amending the 20-Percent Rule to a 30- or even 40-Percent Rule. You can travel too quickly. You cannot travel too slowly.

Manifesto . . . suggests boldness and daring—revolution, even. This is precisely what I need, what we need: a new way of traveling.

Book

BOOK

*Restrictions may apply, see Terranea.com/offers for details.

TRAVEL EMPATHETICALLY

WHEN WE TRAVEL, we usually expand ourselves not by turning inward but by interacting with other people. Do we see only differences—language, cuisine, customs—or do we also identify commonalities, a shared humanity? This is empathy. If we don’t empathize, at least a little, with those we encounter, we never really see them.

Empathizing with other people doesn’t mean becoming them. It’s fashionable to brag that you “travel like a local.” No, you don’t. You travel like a foreigner. That’s because you are one. And that’s OK. The empathetic traveler doesn’t try to fit in. She knows that is impossible and that there are advantages to seeing places at an angle. One of the best books about U.S. democracy was written by a Frenchman, Alexis de Tocqueville. This is no coincidence. An observant outsider often sees what insiders do not.

TRAVEL JOYFULLY

TRAVEL, OF COURSE, is not drudgery. At its best, it is not only meaningful but fun. Otherwise, why bother? Too often, I realize, I’ve either expected too much from a place (and left feeling disappointed) or expected too little and therefore closed myself off to what a place might offer. The solution, I’ve learned, is to expect nothing yet be open to everything.

Expectations are the enemy of happiness. Expectations, even positive ones, rob you of the sudden beauty of a first impression. When I first saw the temples of Angkor Wat in Cambodia, I wasn’t sure if I was responding to the actual place or to some idealized image I’d absorbed from all those Instagram posts. Maybe Angkor Wat really is beautiful; maybe it’s overrated. There is no correct reaction, of course, only an authentic one—and it’s easier to have an authentic reaction if our perspective is unmuddied by the thoughts (and Instagram feeds) of others. That’s why I’ve learned to prepare, but not over-prepare, for a trip. I’ll read historical accounts of my destination but not contemporary ones—and, yes, I really do go on an Instagram fast.

Jettisoning expectations also frees us up for the sort of serendipitous encounters that make travel meaningful and, should the travel gods smile on us, magical too.

Over the years, the travel gods smiled on me quite a lot. Then COVID-19 arrived. I may never travel the same way again, even after the virus is vanquished. Thank goodness. A realignment was long overdue. I wouldn’t go so far as to say the pandemic represents an opportunity, but it has forced me to question my assumptions, to see the world, and myself, a bit differently. And isn’t that what travel is all about?

Eric Weiner has written several stories for afar. He’s also an author, most recently of The Socrates Express: In Search of Life Lessons from Dead Philosophers (Avid Reader Press, August 2020).

WHERE THE PATH LEADS

llllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllll llllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllll llllllllllllllllllllllllllll er fields, alllll lllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllll llll hem, publiclfootpathllllllllllllll llllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllll

GREAT BRITAIN, MY NATIVE LANDSCAPE,lllllllllllllllllllllllllllllll lllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllll lllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllll llllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllll lllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllll lllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllll lllll d to fitnellllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllll lllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllll lllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllll lllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllll

Tlllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllll llllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllll llllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllll llllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllll lllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllll llllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllll lllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllll lllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllll lllllllllll h offerllllll h filllllllllllllllll llllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllll llllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllll lllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllll llllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllll lllll , a field of yllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllll lllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllll llllhe field’lllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllll lllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllll llllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllll llllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllll lllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllll llllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllll lllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllll lllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllll llllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllll llllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllll llllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllll lllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllll lllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllll lllllllllllllllllllllllllll wners, and left offl lllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllll llllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllll lhe officialllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllll llllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllll lllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllll llllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllll lllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllll llllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllll llllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllll lllllllllllllllllllllllllll ifielll lllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllll llllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllll llllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllll lllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllll llllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllll lllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllll lllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllll lllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllll lllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllll lllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllll

Emma John is a contributing writer to afar and the author of lllllllllllllllllllll llllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllll (Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 2019).

by NEGIN FARSAD

by NEGIN FARSAD

A NEW GLOBAL CITIZEN

II guess if I had to put a label to it, I’d call myself a Global Citizen; you know, if push came to shove. Or si la poussée vient à pousser. See? I just dropped some French, and yet I’m primarily writing in English. How Global Citizen of me!

IF I WAS YOUR BOUGIE EVERYWOMAN, the type who went to college, did a semester abroad, backpacked around Europe, watched French films at independent cinemas, and in a pinch, could recall, and even correctly pronounce, the name of the German chancellor, you’d call me a Global Citizen. A woman who’s sensitive to the plight of rural Hondurans and doesn’t confuse them with other Central Americans. Who understands the difference between a crumpet and an English muffin. A woman who gets it.

That woman may be a Global Citizen, but she is the Global Citizen from an era of American life when only certain types were privileged enough to be well traveled.

Parts of me are that woman—the college, the semester abroad, followed by the teaching English abroad, followed by the cashiering and waiting tables abroad. I do see snooty foreign films, and I do feel a pang of recognition when I look at a crumpet. I see you crumpet, I know who you are. But I’m not the every-bougie-woman you may have conjured, because I’m also Iranian and Muslim and the daughter of immigrants. I was raised not just bilingual but trilingual—my parents are from a pesky part of Iran that neighbors Azerbaijan. In that region, you speak not only Farsi but also Azeri. That’s right, I speak all the useful, marketable languages. I’m your bougie everywoman doused in saffron.

I represent an intersection of a thousand things: the Iranian, the American, the Azeri. I’ve lived in Paris, London, on the East Coast, on the West Coast, in the desert, and in the snow. Maybe all of that makes me a Global Citizen. But that’s not really it. What makes me a Global Citizen is that I was raised to love a place I didn’t spend much time in. That I was taught to feel belonging in two countries. Throughout my life, that feeling of belonging has spilled over to nearly everywhere and everyone.

My earliest memory of an international flight didn’t have the glamour of “travel.” I was going to see family in Iran, because that’s where they all were. For me it was the equivalent of visiting the in-laws in Sheboygan. There were no mai tai cocktails or flower leis to welcome us. Instead we were greeted with an announcement on the flight reminding the ladies that before they left the plane, they had to wear the hijab—to cover their hair and the contours of their bodies in accordance with the rules of the Islamic Republic. My mom would whip out a chador and groan. I was a kid, so I didn’t think much of it.

Iran looked different, and yes, a little scary. But still, I had the best times there. Iran was fun! I had so much family, and they constantly threw parties and gave me candy. What

“Traveling like this, at a human speed, an otherwise invisible world revealed itself.”

From Peter Bohler’s “How to See the Morocco Most Tourists Don’t” episode in the new Travel Tales by AFAR podcast

Let these life-changing stories inspire your travel dreams until your next adventure. And with The Marriott Bonvoy Boundless™ Card from Chase and their shared belief in transformative travel, you’ll be well on your way to powerful new experiences.

Presented by

Presented by

more could a kid want? We would go to Iran for many summers and I loved it. I loved this place that was so different and so much more restrictive and yet none of that mattered.

Now I’m married to a Black man—his mother was white and his estranged father was Black. They’re both deceased. He has experienced homelessness, lived a middle-class life, and glimpsed the finer things. His background is similarly a thousand things: It’s American, Polish, Catholic, agnostic, and of course some African heritage he’ll never quite know.

Together, we made a kid, who’s now a toddler, who has my thousand things and his thousand things, which means I have to start doing math. I expect her to love the many thousand things that make her a person. Places she hasn’t seen yet and places she may never see. In fact, she contains too many ingredients to start excluding points on the globe. Instead, she’ll have to embrace them all.

Her first international trip was to Morocco, at just two months old. Her dad is an actor and was on the set of the TV show Homeland. While we were in Morocco, locals kept saying she looked so Moroccan. That she was surely one of them. It made me happy that they were so willing to claim her. We became instant family in those moments. She has that ethnically ambiguous face where she can easily blend into so many countries. But it’s not just thick eyebrows and brown skin—she’s actually made of so many countries.

Our family doesn’t naturally fit on the cover of any country’s travel brochure. Sometimes we look like we’re from the place, sometimes we look like weird sideways versions, sometimes we’re in Finland. So we just build a new category: We belong everywhere we go. We don’t ask. We assume we belong and hope it sticks.

And of course it will. Because my baby shares her Muslim background with more than a billion people scattered around the world; she shares her African background with billions, too; she shares her Americanness with hundreds of millions. It would be too much for her to gerrymander the places that don’t contain her. She has to be empathetic to their shortcomings, proud of their achievements, and worried for their collective future.

Because my daughter is that kind of Global Citizen. She has to travel more thoughtfully. She has to plan long voyages where she can not just see people, but know them. She has to care about the air and the water and the erosion. She has to see places as not just a collection of monuments but as a continuum, and she has to know that when she touches that continuum, she changes it. So she has to be careful with that power. She has to imbue it with love.

But nearly all of us in America fit this description. We’ve each got a thousand things behind us. We’re hyphenated by race, ethnicity, religion—and those are just the obvious ones. We’re also hyphenated by education, sports team, mustard preference, pet selection, and whether or not we believe in bedazzling T-shirts. Some Americans quarantined to jazz and others to Bollywood. Black people marched for Black Lives Matter and Filipino people marched for Black Lives Matter. Our calls to action last year—and this year, this century— crossed and will continue to cross generations, cultures, races, and classes.

So of all the people, in all the world, it should be easy for us to be this kind of Global Citizen— the kind that arrives in a country with care. After all that 2020 heaped on us, I believe that global spark is still with us. Even in the people who bedazzle their T-shirts.

What makes me a Global Citizen is that I was raised to love a place that I didn’t spend much time in. That I was taught to feel belonging in two countries.

is proud to be one of six founding non-profit organizations Center for Responsible Travel, Destination Stewardship Center, Green Destinations, Sustainable Travel International, and The Travel Foundation, with special advisement from the Global Sustainable Tourism Council.

Imagine a global movement that uses travel to change the world.

Welcome to The Future of Tourism.

Decades of unfettered growth in travel and the global pandemic have put the world’s treasured places at risk –environmentally, culturally, socially, and financially.

As travelers, we have a choice - to choose travel providers that prioritize the needs of destinations first. The Future of Tourism Coalition was formed create a powerful collective, uniting more than 400 major travel companies, destinations, governments and non-profits with a global purpose to use tourism to change the world.

To learn more and for a list of companies involved, visit www.futureotourism.org

#FutureOfTourismNothing

There’s no denying that this year has gone a little sideways. But with calm, clear water, warm sunshine, our legendary laid-back attitude and a million unique ways to keep your distance, nothing comes close to a getaway in The Florida Keys & Key West. fla-keys.com

1.800.fla.keys

Largo Cottages

All

Inclusive Activities FREE

A Sun-Kissed Florida Dream

Slip away to the Florida Keys and Key West, where wildlife refuges meet outdoor dining and beaches for a blissful getaway. A visit supports the small businesses and sustainable culture that make this destination special, helping preserve the Keys for generations to come. Read on for recommendations to make the most of your trip.

KEY LARGO

Go snorkeling among the shipwrecks of the Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary or explore the Everglades, then relax by the pool at a bayside hotel.

ISLAMORADA

Paddle around Library Beach Park, go gallery hopping on Morada Way, or enjoy some outdoor dining at spots such as

Islamorada Shrimp Shack or Pierre’s.

MARATHON

Meet local wildlife at the Dolphin Research Center, Turtle Hospital, Florida Keys Aquarium Encounters, or Pigeon Key.

LOWER KEYS

Bike in Bahia Honda State Park or Deer Key Refuge, or visit the Florida Keys

National Wildlife Refuge’s Nature Center.

KEY WEST

Do a little sightseeing at the Hemingway Home, Fort Zachary Taylor State Park, and the Key West Botanical Garden.

For the latest protocols on health and safety in the Florida Keys, please visit fla-keys.com.

From pristine natural wonders to its unique local culture, here’s why the Florida Keys and Key West are the ultimate escape.

Experience Florida’s Most Inspiring Destination

Captivating museums. Iconic historic sites. Exotic botanical gardens. Rediscover what inspires you in The Palm Beaches. Start planning your escape at palmbeachculture.com/escape

Rediscover Arts and Culture in The Palm Beaches

Discover eye-opening museums, sprawling gardens, historic sites, and more places that are as safe as possible— and fun—to explore. Stroll 16 acres of serene gardens that showcase more than 7,000 art objects and artifacts at the Morikami Museum & Japanese Gardens. Hike through history

at the Jupiter Inlet Lighthouse & Museum— one of nine Outstanding Natural Areas in the United States. Or, take a guided tour of a Gilded Age estate at the Henry Morrison Flagler Museum

Whatever you decide, an endless supply of unforgettable

experiences await you in The Palm Beaches.

Start planning your escape at palmbeachculture.com/ escape.

Follow us:

@palmbeachculture

#palmbeachculture

WE VE HAD MONTHS TO DREAM ABOUT OUR NEXT TRIP. WHERE WILLWE GO,WHO WILL WE MEET,WHO WILLWE BE? NOW WE RE NEARLY READY TO GET BACK OUT THERE, UNITED BY HOW THE WORLD SURPRISES AND INSPIRES US.

Where to Go in 2021. It might be more appropriate to ask Should I Go in 2021? And if so, How Exactly Do I Go?

Because 2021, while imbued with hope, is still an unknown. Lockdowns, border openings, and the vaccine (oh, the vaccine) remain in flux. In a time when so much remains uncertain, there are some things we know to be true. The pandemic revealed a world without travel. We learned what we took for granted and what we missed the most. And we know we will go when the time is right. On the following pages, you’ll read about 12 places we’re dreaming of now: A journalist longing to return to Ghana; a novelist’s dream of following, slowly, in the footsteps of her favorite adventurer in Greece; an activist’s desire to travel intentionally and conscientiously in Vietnam. We’re leaving aside the “how” of travel for now—that will come, with time. Because as Desmond Tutu wisely said, “Hope is being able to see that there is light despite all of the darkness.” Here’s to a brighter 2021.

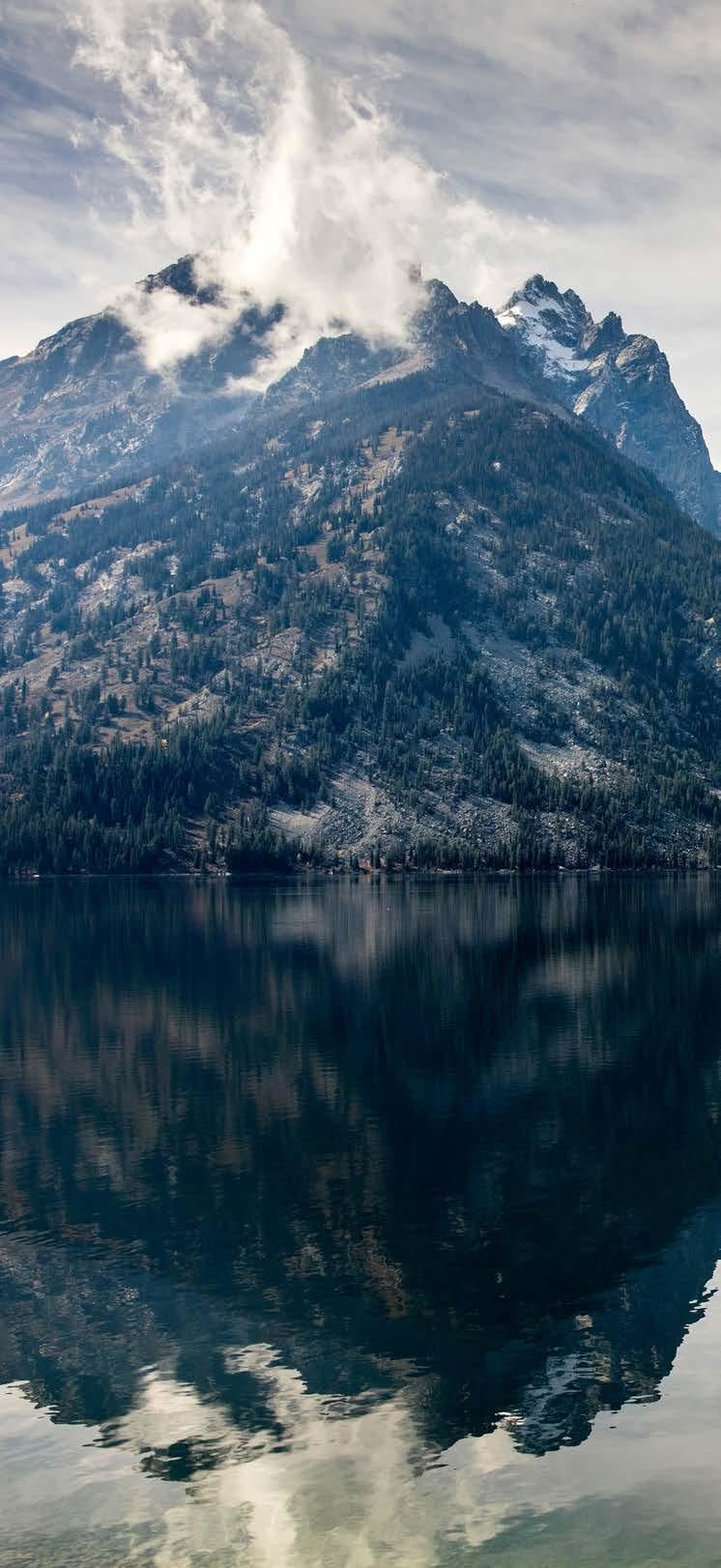

Wyoming

I’M AN EXPLORER of the great indoors. If anyone was prepared to stay inside during a global pandemic, it was me. But I also crave adventure, and I cherish what it means to wonder and to try.

I have cerebral palsy, which might explain the irony of being a wanderlusting homebody. As a child, I scraped my knees out in a world not built for me and learned that home didn’t have as many restrictions. But my mom wanted me to have an after-school activity, so she found a horseback-riding team made up of nondisabled and disabled children. Being outside, high up, moving at a blur-inducing pace was thrilling. I’ve never forgotten that sense of freedom. Now, after months spent indoors as a high-risk individual, riding is what I imagine doing most.

I picture meandering through Wyoming’s Grand Teton National Park on a four-day excursion, stopping only to camp under the stars. I’d be wearing jeans, a shift from my current uniform of sweatpants, and my legs would curve over the sides of a horse navigating rocks and streams. I’d listen to the sounds of birds overhead as a crisp breeze sends the scent of wildflowers through the air, and I’d breathe it in while admiring the park’s namesake mountains scraping at the sky. Mostly, I’d relish a setting where time doesn’t pass painfully slowly or incomprehensibly fast. Those peaks and valleys are just there, as they have been for more than 15,000 years, unmoved by human chaos. I used to prioritized livelier destinations— ones with crowds moving through busy streets and markets and museums and concert halls. Maybe a horseback trip isn’t a new idea, but it feels like the most restorative. I want a slow place to get me back up to speed. Luckily, Grand Teton National Park promises a wideopen adventure, but with plenty of sitting.

Ghana

HEATHER GREENWOOD DAVIS

HEATHER GREENWOOD DAVIS

“I CAN TAKE YOU TO YOUR PEOPLE.”

The phrase was uttered by the elder who had taken my hand shortly after I arrived in a small Ghanaian village in 1997. And though the words were simple, they pointed to a difficult fact: Black people displaced from their homeland by slavery had been severed from their ancestral roots. Now that we were back to visit, those who’d never left the continent could see in us connections we still couldn’t see in ourselves.

My role on this trip was as a reporter. I was sent by my newspaper to accompany a group of Black teenagers who had won the trip, and I’d heard this phrase spoken to others many times. Those who heeded the call were introduced to someone who looked just like them, each time finding an unexpected resemblance through some distant lineage. Now, it was my turn.

The trip was my first to the continent. It was also my first international assignment. I didn’t want to screw it up. I was wary of personal moments that might distract from my perceived professionalism. And so I didn’t follow that woman to “my people.” More than 20 years later, I’m still haunted by that decision.

In 2019, hundreds of thousands of Black people participated in Ghana’s “Year of Return,” an invitation to Black people from across the diaspora to return to the country, 400 years after the first slave ships left the country’s coast. I watched online as they visited the slave dungeons and historic villages I had seen on my own visit. Those memories flooded back—as did that offer of connection that I’d politely declined.

I would make a different choice today. Older and slightly wiser, I see the opportunity I missed. I wasn’t ready then, but I am now. When it’s safe, I will go back. This time I’ll take my kids. I’ll show them the door of no return, where enslaved Africans last glimpsed their homeland. I’ll also introduce them to Ghana’s waterfalls and national parks. And most important, I’ll introduce them to the people shaping the aesthetic of everything from fashion to music on a global scale. We’ll pop into traditional villages in places like Kumasi, but we’ll also marvel at the stilt homes in Nzulezu and the skyscrapers in Accra. This time, I’ll focus on my own experience. And when a hand is offered, I’ll be ready to grasp it and let it lead me home.

Seville

ANYA VON BREMZEN

ANYA VON BREMZEN

IN JACKSON HEIGHTS, New York—the neighborhood I call home, and one of the pandemic’s first epicenters—our early spring days were dark with trauma. Ambulances wailed outside my windows, the news was awash with scenes from overwhelmed Elmhurst Hospital a few blocks away, and I grimly counted my cans of beans, because even the bodegas were closed. During lockdown, I found comfort in mentally revisiting my favorite tapas bars of Seville. How I’ve missed those crowded tiled taverns, the countermen rasping out rapid-fi e pregones (tapas calls): oxtail stew, lacy fried fish, dusky curls of Ibérico ham. But the eats— ¡delicioso!—weren’t the only reason I longed for Andalusia’s capital. Seville is Spain’s most sociable city, with its fiestas and religious processions and its ritual of the tapeo, the bar crawl that refuels the city’s community spirit.

In my fantasy tapeo, I start at La Flor de Toranzo in the historic center, trading confidences with strangers over icy Cruzcampo beers around the ’40s-era zinc counter. The signature tapa? Freshbaked Antequera rolls mounded with anchovies under squiggles of condensed milk. From there, I squeeze onto a rickety stool at Casa Moreno, a spot hidden in the back of a grocery store. Manzanilla in hand, I take in the fearsome stuffed bull’s head on the wall above a cabinet of rare sherries and wines, curated by Emilio Vara, one of Seville’s most beloved taberneros (barkeeps). Emilio’s “kitchen” is a single beat-up toaster oven churning out warm montaditos—small canapés—“plated” on squares of wax paper. Son of a well-known local journalist, Emilio pours his creativity into penning aphorisms on stickers—“Joy makes us invulnerable,” “Haste destroys all tenderness”—and into entertaining his regulars. A good tabernero, he says, is above all a psychologist.

I finish with batter-fried bacalao and braised Ibérico pork cheeks at the nearby Bodeguita Romero. Here the same blue-haired widow shows up to eat every day at noon, smartly dressed and coiffed. The bars of Seville, she once observed to me, are the city’s kitchens, its living rooms, its confession booths. Without this human connection—she gestured proudly around us—how would we ever survive?

Anya von Bremzen is an AFAR contributing writer and the James Beard Award–winning author of six cookbooks and a memoir, Mastering the Art of Soviet Cooking

Ilha Grande, Brazil

A DECADE AGO, I went with one of my besties, Anyeley, to Brazil. We travel well together, which is a coup for wildly different people—Anyeley is an African American practicing Christian and I’m a secular Iranian American Muslim. At the time, we were single gals in grad school. Despite having none of the luxuries of travel, we managed to have the time of our lives.

So when we’ve talked about our first postpandemic trip, it’s to Ilha Grande, an island off the coast of Rio. The island is small and walkable with unbelievably pristine beaches. It’s not a party island, though there is partying; it’s not a sleepy island, though there are plenty of ways to relax; it’s not an island propped up by festivals or by the wealth of a few. Ilha Grande is a destination that somehow provides whatever it is you want from it.

Back then, we wanted dancing and beaches. We found both on Lopes Mendes, a beach accessible by boats helmed by teenage boys who want to terrify passengers with their wave jumping. Every day, there was swimming and dancing—so much dancing. People would dance at sunset on the beaches; they would dance on the paths of Abraão, the main town, at night.

At one point we walked into a bikini shop, looking for the Brazilian bikinis locals wear as easily as sweatpants. As the elderly shop clerk rang us up, she invited us to her Bible study. Anyeley was floored. “That’s what Christianity can look like,” she said as we left. “You can sell high-cut bikinis and promote your Bible study—I love it!” I loved that too, the way the entire globe can shrink down to three very different people.

I wonder what our future trip will look like. Will we brush up against the issues that have divided the U.S.? Or will we find bikini shops run by Bible-thumping Brazilians who could somehow bring us closer together?

When Anyeley and I inevitably go back, we won’t stay at a hostel, and we won’t be as brazen with our swimwear. But I know that in that casual Ilha Grandean way, the island will somehow provide us with a magical thing we need. Years ago, that was dancing and cute boys, but because we’ve been deprived of our togetherness, maybe this time around, togetherness is all we need. That and some terrifying wave jumps.

Negin Farsad is a writer, comedian, and actor based in New York City.

The bars of Seville, she once observed to me, are the city’s kitchens, its living rooms, its confession booths. Without this human connection—she gestured proudly around us—how would we ever survive?

CRUISE CRITIC Cruisers’ Choice 2019

PORTHOLE Best Itineraries 2020

TRAVEL AGE WEST Wave Awards 2019

TRAVEL WEEKLY UK Cool Cruises 2019

Holland America Line is an authorized concessioner of Glacier Bay National Park. We are currently assessing enhanced health and safety protocols in light of COVID-19 and how they may impact our future offerings. Our actual offerings may vary from what is displayed or described here. Stay updated on current Travel Advisories and health and safety protocols at hollandamerica.com. Ships’ Registry: The Netherlands.

Holland America Line is an authorized concessioner of Glacier Bay National Park. We are currently assessing enhanced health and safety protocols in light of COVID-19 and how they may impact our future offerings. Our actual offerings may vary from what is displayed or described here. Stay updated on current Travel Advisories and health and safety protocols at hollandamerica.com. Ships’ Registry: The Netherlands.

SEE ALASKA WITH THE BEST

Dreaming of seeing the Great Land? Trust the cruise line voted Best in Alaska in the 2020 AFAR Travelers’ Awards. This award, and several others, are why we say We Are Alaska. As one of the few cruise lines with access to Glacier Bay National Park & Preserve, we also offer more itineraries that include this UNESCO World Heritage site than any other cruise line. Our spacious ships are known for award-winning dining, the best live music at sea, and service that brings guests back again and again. Extend your adventure to our own resort at Denali National Park and even explore the Yukon’s gold rush history. We’ve shown guests the majesty of Alaska for nearly 75 years, and we’d love to show you as well.

The Mani, Greece

THERE’S SOMETHING hallucinatory and steadying about Greece’s landscape, the elemental wind and dazzled light, its scoured crags and wine-dark sea (to use Homer’s phrase). My husband and I used to make regular pilgrimages to the Cyclades; then came the joyous upheaval of children, followed by years of unmooring—the passing of parents, half a dozen relocations, a devastating house fire, the uncertainties of midlife and marital strain.

And now the unsettledness into which we’ve all been thrown. I suppose it’s no surprise that I find myself fantasizing again about Greece, where the simplest things can seem so profound. Just to sit for a plate of horiatiki (salad) at a seaside taverna is to participate in a ritual seemingly untarnished by the passing of time. In particular, I’ve been thinking of the barren cliffs and vermilion-stonedvillagesofaregionInever made it to, on the southernmost tip of the Peloponnese: the Mani. There, my favorite British adventurer built his home among olive groves confronting the expansive sea, as if to settle into permanent contemplation of eternity.

It’s easy to fly to now, but in 1951, when the late Patrick Leigh Fermor trekked there over the Taygetus range, the Mani was virtually inaccessible to outsiders. Leigh Fermor was a sort of Byronian 20th-century knight who had set out earlier, at age 18, to walk from Holland to Constantinople, sleeping in haystacks and carousing in beer halls and wooing a princess along the way. At one point in Mani, the chronicle of his Greek journey published in 1958, Leigh Fermor describes swimming from a fishing boat to the cave known as the entrance to Hades, a surprisingly serene experience.

What I dream of now is what Leigh Fermor called a “private incursion” into the Mani: not a conquering of its Byzantine chapels or medieval embattlements or towering peaks, but a wandering along cobblestone paths and sun-bleached shores. Shores that hint at myth and perpetuity, in the way that only Greece can.

Charmaine Craig is the author of the novels The Good Men, a national best seller, and Miss Burma, long-listed for the 2017 National Book Award for Fiction. She lives in Los Angeles.

CHARMAINE CRAIG

I suppose it’s no surprise that I find myself fantasizing again about Greece, where the simplest things can seem so profound.

traveled to Arizona with Learning

Since 2009, Learning AFAR has transformed the lives and communities of thousands of disadvantaged students through the power of travel. With today’s challenges, your support makes the crucial difference in nurturing the leaders of tomorrow.

“Since the program ended I found myself taking charge, finally having confidence in myself.”

—Stephanie, a student who

AFAR

Vietnam

HOW DOES AN AMERICAN travel responsibly in Vietnam? It’s been on my mind this year, a year when many of us are thinking more deeply about the effect we have on the places we visit. I passed through Vietnam briefly almost 20 years ago, but I’ve always wanted to spend a month in the country, savoring spring rolls while skipping about between historic temples and palaces. But if I aspire to be an American with a conscience, should Vietnam even be on my vacation radar? How can I do the relaxing, vacationy things and, simultaneously, reckon with such a complex, often brutal history—one that my own nation helped create?

To avoid Vietnam—to avoid the discomfort of history—feels problematic, too. So in 2021, once the country has reopened to visitors, I’d like to plan a responsible trip, in every sense. I’d start in Ho Chi Minh City (and would call it that rather than its French imperial name, Saigon). I’d tour the War Remnants Museum, which until 1995 was called the “Exhibition House for Crimes of War and Aggression.” I’d spend a day with Tiger TourstolearnaboutthewarfromtheVietnamese perspective. And I’d stay at the Myst Dong Khoi, part of a locally owned group of hotels.

I’d go to Da Nang, the coastal city where U.S. troops first landed, and visit Son My, where American troops massacred more than 500 villagers in one of the bloodiest events in the war. There’s a memorial there, as well as the ruins of an ancient temple. Throughout my trip, I would eat at small, family-owned restaurants, which grew out of postwar economic reforms that made it possible for many Vietnamese to open their own businesses in this still-communist nation.

And yes, eventually, I might go to a beach near another coastal city, Cam Ranh, maybe stay at the Anam, another Vietnameseowned luxury resort. There, I might relax into the soft sand and swaying palms—but I’d think about the American military personnel who once sat in the same spot, against the backdrop of ruination. There is no escape from history. Sometimes travel, when our minds are most open, is the best way to connect with it.

Barbados

THE BUSSA EMANCIPATION STATUE is unmissable. Located in the middle of a busy roundabout, it depicts a man in tattered shorts, his hands outstretched, broken chains hanging from the shackles on his wrists, and his eyes looking up at the blue Caribbean sky. Barbadian sculptor Karl Broodhagen created the piece in 1985 to commemorate the abolition of slavery in Barbados in 1834. When I first saw it from the window of a taxi in 2016, I was taken aback by its unflinching depiction of the brutal enslavement of a people. But it wasn’t melancholy—it was prideful. I wondered if Bajans, as Barbadians are also known, thought about that history as they zoomed by in their cars.

A locale shows its ethos in the details. During that trip, I saw how Barbadian culture has been shaped by enslaved Africans and their descendants. I felt it in the sway of exuberant soca music spilling out of cars and shops, at bars where locals and tourists talked and laughed over rums that were once produced by slaves on the island. I tasted it in the national dish: flying fish native to the waters around the island, stewed with tomato and onions. It’s served over cornmeal and okra cou-cou, similar to Southern grits—both inherited from banku, Ghana’s ubiquitous fermented cornmeal and cassava dumplings. When I ate the dish at Primo in St. Lawrence Gap, overlooking the Atlantic Ocean, I was experiencing, through these ingredients, the connection between all the places the transatlantic slave trade touched.

In the United States, as we continue to confront this country’s legacy of enslavement, I’ve thought often of Barbados and of the statue: It reminds me that it’s absolutely necessary to acknowledge our history and face it squarely, so that we don’t repeat it. Sure, you can visit the island for the (excellent) rum bars and beaches, but the true magic of Barbados lies in embracing its entire story. For me, a Black woman traveler, my next trip to the island will feel like a return in more ways than one.

Korsha Wilson is a graduate of the Culinary Institute of America and host of A Hungry Society, a podcast that takes a more inclusive look at the food world.

If 2020 has taught me anything, it’s that the next flight is no longer something to take for granted—and once it’s safe to venture out again, this long-overdue holiday is something I won’t put off any longer.

Uzbekistan

SARAH KHAN

SARAH KHAN

MY FATHER, the unofficial family historian, can trace our ancestry back 40 generations and across nine modern-day countries, including Saudi Arabia, Spain, Turkey, Uzbekistan, India, and the United States. I’ve lived in or traveled to many of those places: I grew up in Saudi Arabia, I’ve been to Spain and Turkey, and I return to India every year. But one thread of my heritage has always felt enigmatic: What, I wonder, were the lives of my ancestors like in 16th- and 17th-century Uzbekistan?

I had lofty goals of tracing the footsteps of that branch, the Rifaees, in 2020, when I started plotting a family trip to Samarkand and Bukhara, both prominent stops along the Silk Road. Landlocked Uzbekistan was, for centuries, a vital hub for Islamic scholarship and culture, and its location drew travelers from across the Muslim world— including many who, like my ancestors, decided to stick around for a few generations.

I sketched out a dream itinerary, based on years of late-night research. I’d take my parents to the imposing Registan Square in Samarkand at sunrise, to see the morning light gild the turquoise tiles of the three grand madrassas, or religious schools. We’d pray in the Bibi-Khanym Mosque, once the largest in the Islamic world. There’d be a break to try pumpkin manti—traditional stuffed dumplings—at a rooftop café overlooking Bukhara’s Po-i-Kalyan complex. We’d search for references to our ancestors in madrassas and necropolises, looking for any clues that could help us see them as more than just names on a family tree. I figured out all this detail before I’d even booked a flight—and then the pandemic put the brakes on my Uzbek aspirations.

My parents are the reason I travel: They carted me all over the world growing up, and thanks to them, some of my earliest memories are of scampering down airplane aisles. I had envisioned this Uzbekistan adventure as a way to say thank you for passing the torch, that now it’s my turn to take them around. If 2020 has taught me anything, it’s that the next flight is no longer something to take for granted—and once it’s safe to venture out again, this long-overdue holiday is something I won’t put off any longer.

Award-winning travel writer Sarah Khan has lived in five countries on three continents. You can find her byline in the New York Times, the Wall Street Journal, Saveur, and many other publications. Follow her on Instagram and Twitter @BySarahKhan.

EuroVelo 6

A FEW YEARS AGO, on assignment in Austria, I found myself on two wheels, rolling through bicycling heaven. Sixty miles west of Vienna, on a bike path along the banks of the Danube, the sun shone through wispy clouds onto terraced vineyards that stretched up the hills. I took a bite of an apricot, just picked from a small mound left outside a farm for passing cyclists. A sign indicated the route I was traveling:EuroVelo6.Iwroteitdown—andpromptly forgot about it.

Likesomanyotherssearchingforwaystogetout into the world safely, I fell more deeply in love with cyclingin2020.Bysummer,Iwasleavingmyapartment in New York City for days at a time, panniers packed and my phone primed for navigation only. Then I started thinking bigger.

I thought of EuroVelo 6. It turns out, I had traversed less than 1 percent of a bike route that extends across 10 countries in Europe, from France to

Romania,theAtlanticOceantotheBlackSea.Could I really do all 2,765 miles of it, through burning sun and cold rain, going days at a time without even the hope of a shower? Before the lockdown, I’d have said, “No way.” Now I say, “Why not?” I researched each section: from the developed trail through the middle of France to the rougher portion—more dirt, less pavement—snaking some 700 miles from Budapest down into Serbia, then through Romania and Bulgaria, until it reaches the Black Sea.

As I mapped it out, Europe was heading for yet another wave of COVID-19 cases, and Americans were still prohibited from traveling to most places. But what are pipe dreams if not delayed plans? Sometime in 2021, I will clear my calendar, get on a bike in Nantes, France, and ride east. I’ll be alone and outdoors, perfect social-distancing conditions. I wonder if apricots will be in season by the time I hit Austria.

Like so many others searching for ways to get out into the world safely, I fell more deeply in love with cycling in 2020.

SEBASTIAN MODAK

Mexico City

AT THE BEGINNING OF JULY, the streets of Mexico City were quiet. Restaurants had just been given the permission to offer indoor dining, and my friends and I walked through the Roma Norte neighborhood in search of seafood. We skipped across multilane thoroughfares where just four or five cars were stopped at traffic lights, as we talked loudly in English and Spanish, our voices echoing in the empty streets.

Mexico City wasn’t the crackling megacity I’d fallen for on my first trip back in 2004. Then, the city’s arteries flowed with greenand-white VW Beetle taxis, the traffic a constant roar. As I explored the Bosque de Chapultepec, the Museo Frida Kahlo, the ancient pyramids outside the city, I made new friends: Mexican teachers, Guatemalan políticos (in one case, a política), Panamanian actors, Spanish entrepreneurs, U.S. journalists.

We’ve stayed in touch all these years. Even more than the tacos at Orinoco, my friends are the reason I visit Mexico City, the reason I’ve built a relationship with it. They are the reason I got on a plane in July, unsure of what I’d find. Mexico City was, in many ways, just another place rendered dormant by the pandemic, the electricity generated by some 20 million people turned down low. But “low” isn’t “ff .”

Walking toward Contramar, Gabriela Cámara’s legendary seafood restaurant in Roma Norte, we heard laughter through face masks and encountered new street art: a vintage automobile covered with lacquered flowers and ferns. We took selfies. The city simmered.

We ordered calamari at Contramar, where the always polite waitstaff wore face shields and latex gloves. In solemn recognition of the pandemic, we lowered our laughter. But we laughed, nonetheless.

The road to recovery won’t be swift. But I know I’ll go again next year, when Mexico City is amped all the way up: loud, lively, and full of love.

New Orleans

THE STICKY HEAT that rises from the sidewalk has never deterred me from fulfilling my New Orleans cravings: For the last several years—until 2020— I’ve made an annual pilgrimage for the crispy fried chicken doused in Crystal hot sauce at Willie Mae’s Scotch House, charbroiled oysters bubbling with Parmesan and butter at Drago’s, steaming po’boys with fried catfish at Parkway or Adams Street Grocery, a muffuletta that I can barely fit into my mouth (still, I make it work) at Verti Marte.

My love for New Orleans is a sensory addiction that began with taste—those bayou flavors were first introduced to me in Los Angeles by my grandmother Gwendolyn, who learned from her mother Emily, born in New Orleans. No matter what kitchen I am in, the stirring of roux to create gumbo invokes a yearning for the place that is a symbol of my family’s great migration West, of fl vors and oral histories passed from mouth to mouth and onto plates.

I know that my great-grandmother’s life in New Orleans was nothing like my annual visits full of freedom, Pimm’s Cups, jazz, and fried foods. I know that her sacrifices, like those of many New Orleanians, exist far beyond the noise and neon signs of Bourbon Street, in deep backwoods and near lakes, between the walls of shotgun homes. Those sacrifices can be seen on sunken houses that still read “save us!” years after Hurricane Katrina, on streets with second line parades, where life and death are equally celebrated.

I will return as soon as I can: to honor my great-grandmother’s memory, to dance and sing with the brass bands, to celebrate the flavors that have become tradition to me each visit. Until then, despite distance, my memories sustain me—they make New Orleans so real, I can taste it.

Kristin Braswell is a writer and entrepreneur committed to changing the world through travel. She has visited more than 20 countries, creating lasting memories with people and places that inspire her brand, CrushGlobal.

Even more than the tacos at Orinoco, my friends are the reason I visit Mexico City, the reason I’ve built a relationship with it. They are the reason I got on a plane in July, unsure of what I’d find.OPPOSITE PAGE, CLOCKWISE FROM TOP LEFT: KATE BERRY, NICOLE FRANZEN, MATHIAS WASIK. THIS PAGE: ZACHARY C. BAKO

ROLAND WATSON-GRANT

Tibet

DEAREST TIBET,g

gggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggg gggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggg ggggggggggggggggggggggg e. I first heargggggggggggggggg ggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggg ggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggg ggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggg

ggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggoff tggggggggggggggggg ggggggggggggggggggggggggg ggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggg gggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggg ggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggg

gggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggg ggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggg gggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggg gggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggg

ggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggg gggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggg ggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggg ggggggggggom manigggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggg gggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggg

ggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggg gggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggg

gggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggg ggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggad to find Xggggggggggg

ggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggg

ggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggmomos ggggggg gggggggggggggggg

ggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggg gggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggg

ggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggg

gggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggg ggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggg

gggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggggg

ggggggggggggggggggggggggg

Roland Watson-Grant’s first novel, gggggggg (Alma Books, 2013), has been translated into Spanish and Turkish. Watson-Grant is the recipient of a Musgrave Medal in his home country, Jamaica.

COMPASS

From our partners: your guide to the best the world has to offer

KNOW THE FEELING OF THE BEACHES OF FORT MYERS & SANIBEL, FLORIDA

At the right pace and in the right place, time slows down. Get to know that feeling again when you’re ready to travel. See where you can take the day at fortmyers-sanibel.com.

FIND YOUR PERFECT BEACH IN SOUTH WALTON, FLORIDA

Located on Northwest Florida’s Gulf Coast, South Walton is an upscale destination that boasts 26 miles of sugarwhite sand, turquoise water, and 16 acclaimed beachside neighborhoods, each with its own personality and style. South Walton’s artful mix of shops and restaurants perfectly complements the area’s beautiful natural attractions. Learn more at visitsouthwalton.com.

HOW TO VISIT SOUTH AUSTRALIA…RIGHT NOW

Discover a real moment of Zen by making a virtual visit to gorgeous South Australia. Bursting with unique natural and cultural treasures, this Down Under state is easy to explore from home, thanks to the wide collection of immersive videos and virtual tours on South Australian Television, or SATV.

Wander among myriad places within striking distance of bustling Adelaide. Virtually cruise the winding Murray River—Australia’s longest—then taste your way through the vineyard-laced hills of world-famous Barossa Valley. Marvel at fuzzy koalas and kangaroos on Kangaroo Island, then jump in the water with sea lions and dolphins on the Eyre Peninsula.

AFAR cofounder Joe Diaz has his own star turn on SATV while recounting his travels there, reveling in the energy and diversity and dishing on his favorite places. Use his tips—and all the inspirational tours on the website—to craft a real-life plan for visiting the magical playground of South Australia.

Experience the wonder for yourself at southaustralia.com/satv-usa.

THE CRISIS HAS REMINDED US OF THE BEAUTYAND FRAGILITY OF OUR PLANET, A PLACE FULL OF WONDERS TO BE EXPERIENCED.

WHEN YOU ARE READY, THE WORLD AWAITS.

HIGHER

by Peggy Orenstein

PERSIST by Julia Cosgrove

TUSCANY BY THE BOOK by Lisa Abend

by Peggy Orenstein

PERSIST by Julia Cosgrove

TUSCANY BY THE BOOK by Lisa Abend

HIGHER GROUND

On a trip through the less-visited corners of Yunnan, China, writer Peggy Orenstein discovers the true meaning of paradise.

Photographs by DIANA MARKOSIAN

Illustrations by ELIZABETH SEE

Photographs by DIANA MARKOSIAN

Illustrations by ELIZABETH SEE

I WAS SITTING IN THE one-room hut of a Tibetan nomad, a wizened old man I’d met while hiking through the Baima Snow Mountain Nature Reserve, a protected wilderness in the far northwest of China’s Yunnan province. My lungs, already straining for breath at an altitude of nearly 12,000 feet, were choked by the smoky fire at the center of the room, and I was trying not to think about the five-mile climb back to the trailhead. The man gestured toward his two butter churns. He showed me a wood cabinet filled with rounds of yak butter that he made and sold to monasteries, where monks plunge their fingers into ice water before carving the blocks into elaborate lotus blossoms, chrysanthemums, images of Buddha. He offered me a cup of something thick, yellowish-white, and slightly chunky: milk, produced by his yaks, that he’d fermented for several days. I sipped. It was sour and fizzy and, admittedly, a little personally challenging. But it was like nothing I’d ever tasted, in this place that was like nowhere I’d ever been, with this person who was like no one I’d ever met. I drained my cup and thought: Welcome to paradise.

I would recall that moment often while driving through the “three parallel rivers” region, where the Yangtze, Mekong, and Salween rush down side by side from their headwaters, all within 55 miles of each other. My 10-day driving trip followed a centuries-old trade route through deep-cut gorges and over Himalayan mountains, from the ancient town of Lijiang to a city that in 2001 was rebranded “Shangri-La” by the Chinese government, which claimed it was the location mythologized in James Hilton’s 1933 novel, Lost Horizon. That may be true. Or not, since Hilton never actually set foot in China, though he did apparently consult the writings of Westerners who lived in this region. Still, that bureaucratic sleight of hand seemed apt. Visitors to China invariably bump up against the government’s Big Brother edicts—what you’re allowed to see and what you’re not, what is real and what is for show, what is tolerated and what is obliterated. Of course the country’s utopia, too, would be defined by decree. As I passed by farmlands dotted with Buddhist stupas, through towering forests, and along rivers running red with silt, my hope was to find something less scripted and more true: the bliss and grace of the unexpected. My journey, taken just months before the COVID-19 pandemic began, was part of the individually customized “Songtsam Circuit” named for (and developed by) a series of small luxury lodges. The inns, where I spent

my nights, were established by Baima Duoji, a Tibetan former documentary filmmaker for CCTV who grew up in a farming town near Shangri-La and wanted to introduce visitors to the culture and hospitality of what used to be a rarely traveled region. “Songtsam” means “heaven” in Tibetan—that promise of paradise again. Each lodge is integrated into a remote village, all of them places that would be difficult to discover as a non-Chinese traveler and virtually impossible, without a knowledgeable guide, to experience in any depth. The lodges’ staff, architecture, and cuisine all draw from the surrounding ethnic populations, providing the sense that nearby communities are being supported, not appropriated.

Duoji wants guests to feel “taken care of as they were when they were children,” reflecting the Buddhist idea that (as a result of reincarnation) any of us could, in some life, have been anyone’s parents, and any place may have, in truth, once been our home. In practice, that meant that, late my first afternoon, blurry from jet lag and culture shock, I was welcomed to my Lijiang digs with handcrafted slippers along with home-baked barley cookies, fruit, and tea. I wandered hallways that were sumptuous with thick carpets, hand-laid timber flooring, panoramic views, and exquisitely curated art, ranging from stone statues of Green Tara, a female bodhisattva of wisdom and compassion, to polished brass and lacquer vessels and mandalas inscribed on silk. For dinner, I was urged, repeatedly, to order more than I could possibly eat—pork ribs fried with tangy local plums; briny, house-cured ham; beef stir-fried with Cordyceps, a fungus grown on insect larva (way more delectable than it first sounded to me); fried chickpea jelly (ditto). Returning to my room, I found a thermos of hot, creamy milk placed next to my bed, fresh from the cows lowing beneath my window. With all

due respect to my mom and dad, my childhood was never like this! Another thing: My guide, a 29-year-old Tibetan woman named Lhatso, addressed me, in all sincerity, as “dear Sister.” I soon began reciprocating, because truly, who knows?