HOW TO OVERCOME THE PROBLEM OF MILK SCARCITY AND LOW PROFITS FOR DAIRY FARMERS AND PROCESSORS?

Results and conclusions of a dairy supply chain and value drain analysis in Albania

Christoph Arndt, Henk de Lange, Dr Artan Xhafa AFC Agriculture and Finance Consultants 12 April 2023

Christoph Arndt, Henk de Lange, Dr Artan Xhafa AFC Agriculture and Finance Consultants 12 April 2023

PUBLISHED BY:

AFC Agriculture and Finance Consultants GmbH

Baunscheidtstr. 17; 53113 Bonn; Germany

T +49-228-923940-00

F +49-228-923940-98

E christoph.arndt@afci.de; ninakristin.thurn@afci.de

I www.afci.de

Project: Sustainable Rural Development (SRD) in Albania

Authors: Christoph Arndt, Henk de Lange, Dr Artan Xhafa

Design/layout: Christoph Arndt

Photo credits: Artan Xhafa

On behalf of

Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) GmbH

Tirana, Albania April 2023

DISCLAIMER:

This study was made with the financial support of the German Development Cooperation via the Deutsche Gesellschaft für internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) in partnership with the Albanian association of dairy processors IPQ The authors take full responsibility for its contents. The opinions expressed do not necessarily reflect the views of GIZ, the German Federal Government or IPQ. The authors can be contacted via e-mail: Christoph.Arndt@afci.de or via mail: Christoph Arndt, AFC Agriculture and Finance Consultants GmbH, Baunscheidtstr. 17, 53113 Bonn, Germany

O N T E N T S

ABBREVIATIONS

aAa Animal Analysis Associates (method of selecting the most appropriate bull)

AFC Agriculture and Finance Consultants GmbH

AI Artificial Insemination

ALL Albanian Lek

Baxhos Small dairy processors in Albania

BB Belgian Blue (cattle breed)

CCI Cow Comfort Index

CEFTA Central European Free Trade Agreement (7 non-EU states in Europe)

EU European Union

GIZ Deutsche Gesellschaft für internationale Zusammenarbeit GmbH

HACCP Hazard Analysis and Critical Control Points (Food safety principles)

HF Holstein Friesian (cattle breed)

INET Dutch milk production index as a method of selecting the most appropriate bull

IPARD Instrument for Pre-Accession Assistance for Rural Development of the EU

IPQ Industria e Përpunimit të Qumështit (Albanian association of dairy processors)

LED Light emitting diode (lighting system)

PC Personal computer

PV Photovoltaic panels for electricity generation with solar energy

SCC Somatic Cells Count (measure of identifying cow mastitis in milk)

TPC Total Place Count (measure of the micro-biology status of milk)

TPI Total Performance Index as a method of selecting the most appropriate bull

VAT Value Added Tax

SUMMARY

This report analyses why there is currently not enough domestically produced milk in the Albanian market. The main cause can be traced back to farming: Milk yields are low and technology is used which prevents family farms from growing. Dairy processing companies therefore rely on imported raw materials (milk or milk products) which are usually of inferior quality and come at a higher cost than if produced locally.

The main weaknesses at farm level can be grouped into 5 categories:

1. Farmers use feed rations which are not in balance and do not make best use of the fodder resources that can be produced on-farm

2. Farmers do not keep records of the productivity and lactation cycle of their cows; this makes herd management difficult, increases veterinary costs and prevents farmers from improving overall annual milk yields

3. Stable conditions are not in harmony with animal welfare principles leading to low fertility and poor milk yields; there are issues with the size and floor of berths, lighting, ventilation, cleanness, milking hygiene and lacking opportunity for mechanisation

4. Heifers and cows are not inseminated at the most appropriate time and they are not controlled for pregnancy; this is one of the reasons why animals are not making most of their genetic potential and calving intervals are relatively long

5. Poor claw health was identified as one of the most important factors affecting milk yield and fertility; specialised claw trimming services are lacking and there is no habit of regular, prophylactic claw trimming

At the level of processors, it was found that farm and milking hygiene as well as animal health are not rewarded via a quality-based milk payment system as farmers are usually paid on the basis of milk quantity and fat content only.

The report calls for capacity building of farmers and all actors around the farm including veterinarians and sourcing managers of dairy processing companies. In addition, the report identifies the need to stimulate investment into new cow stables or the reconstruction of old stables into units which respect the basic principles of animal welfare. Furthermore, investments into farm machinery are needed for the harvesting of fodder and the handling of manure.

1. INTRODUCTION

The dairy sector is an integral part of sustainable agriculture. It makes best use of field fodder grown as part of the crop rotation. It supplies manure for field crops, used either directly or via composting. In the household economy, it generates daily income for farms and allows for a cash flow which helps farmers to bridge financial gaps between two harvests. Dairy production differs from poultry and pork production as it has been most successful when it draws on the land resources available at farm and community level.

However, the number of ruminant animals (cows, goats, sheep) is declining rapidly. In 2018, 343,000 cows were still counted while in 2021, this number decreased to 278,000 cows (Instat, 2022). The drop in cow numbers has amplified in 2022, when grains became expensive. Milk scarcity in August 2022 has led to a surge in raw milk prices from 40-50 ALL to 60-70 ALL, as milk processors need more than 150,000 t of raw milk per year to satisfy the local market and generate a return on investment. However, dairy companies are now collecting less than 100,000 t per year, and prices remain high (about 75 ALL per kg plus VAT in February 2023).

Milk scarcity in Albania hints at underlying problems which the dairy sector in Albania faces. From company visits along the value chain it can be easily concluded that the weakest link in the dairy value chain is the dairy farm: The trend that many small farm households are getting rid of their milking cows now that feed and fodder get expensive on the market is commonly known. It is also common ground that only few middle-sized dairy farms have appeared and that they are generally struggling with low productivity and high unit costs. To understand the reasons why and design action to support dairy farms of this middle-sized segment, we carried out a thorough analysis at farm level of those farms which are part of supply chains allowing dairy companies provide dairy products to the Albanian consumers every morning.

In addition, we analysed the supply chain from the processors’ points of view mapping milk flows and assessing productivity leakages. While Albania’s processors have the capacity to make first class dairy products (cheese, yoghurt and fresh milk), productivity losses mostly have to do with the quality of raw milk they receive. The major problems therefore need to be tackled at farm level and at the farmerprocessor interface.

2. METHOD

During two visits in October as well as November/December 2022, 24 farms supplying 5 dairy companies were visited by the authors. Together, these dairy companies are responsible for about 70% of the dailytrade with dairy products in Albania. The 24 farms represent three typical groups of Albanian dairy farms: ►Up to 20 milking cows, ►21-50 milking cows, and ►more than 50 milking cows.

Figure 1: Characteristics of the 24 sample farms

For the assessment of the processing segment of the dairy value chain, the five above mentioned companies were interviewed to better understand i) from where each of the five companies source milk and which markets they serve and ii) how the value of raw milk increments from farm gate via processing to retailing and finally consumption. Value increments along the value chain together with cost data at each segment of the chain provide information about possible inefficiencies along the chain or imbalances in the distribution of value to the actors along the value chain. This study also includes findings of a workshop held on 26 May 2022 with representatives of the 8 major processing companies in Albania and their association IPQ (Industria e Përpunimit të Qumështit) in which major challenges of the dairy value chain were aired from the point of view of dairy processors. In addition, the results of a food safety assessment according to HACCP of 7 small dairy processors (“baxhos”) are referred to in the Chapter on bottlenecks at processor level.

3. MAJOR FINDINGS

Assessments of suppliers and dairy processing companies substantiated the hypothesis that the weakest link in the supply chain is the dairy farm although also at the farmer-processor interface and at the level of policy and taxation change needs to happen.

3.1 Farm level

At farm level, weaknesses can be easily demonstrated via productivity parameters (Figure 2). The findings in this table could be used as a baseline in order to determine any progress made by government or project intervention.

Figure 2: Productivity parameters as measured during the assessment of 24 dairy farms

N.B. Where average and median is close to each other, only the average is given. Where there is a large discrepancy, the median is provided as it rather shows a value for the typical farm. All values are based on expert estimation and interviews as herd management data is generally not kept.

* only of farms that have land

As a conclusion, milk yield is too low for the relatively high intensity level (0.12 EUR concentrate feed costs per kg of milk). With alfalfa abundantly available and the farmer’s readiness to pay good money for concentrate feed, the milk yield should be at least 7500 kg. An average yield of 14 t dry matter of alfalfa (about 36 t of fresh matter) from 4-5 cuts per year is surprisingly high and should be a good base for low-cost milk production. With 0.8 ha of land per livestock unit there should be sufficient land to produce the necessary fodder.

Another conclusion is that the calving interval is too long. It should be in average 370 days, but 4 farms (16%) even had calving intervals of over 400 days. Both, milk yield and calving interval are key parameters for productivity, and with the figures we found, it can be concluded that farmers are at risk of losing money.

About the other parameters in Figure 2: 46% of young stock seems to be on the high side as usually only 35% is needed for replacement. On the other side having more young stock on the farm allows it to grow which could be interpreted as a good sign.

The relatively high share of farms using only family labour (50%) is remarkable as it can be assumed that family farms in general are more resilient and oriented towards long-term development. Overall, the workforce per 100 cows is extremely high. With the help of technology and optimisation of processes, the same number of workforce per farm should be able to keep at least twice the amount of cows.

Virtually all farms were in the possession of at least one tractor. This helps with improvements in the area of crop-livestock integration.

In a nutshell, it was found that while the genetic potential of the cows was good and they were mostly fed well, major health problems were detected: Mastitis, untrimmed claws and low fertility. Another critical area was found to be housing and management. Usually, cows are not grazing; nearly all visited farms have the cows inside 24/7. Serious animal welfare problems were detected which translate directly into a low milk yield and contribute to poor milking hygiene: Lying on concrete, scarce use of litter, missing ventilation, poor lighting, berths which are generally too small. Simple record keeping for herd management is not made. This implies that underperforming or sick cows are not easily detected. Little is done to prevent animal health and fertility problems, while the willingness to pay for veterinaries’ curative services is strong leading to relatively high expenses for vet visits and drugs.

3.2 Processor level

An analysis of the data generated from dairy processing companies about the raw milk they buy from farmers and the ready products they distribute to Albania’s retailers underline the major challenge of the dairy supply chain, i.e. to reduce the dependency on raw milk imports.

UN Comtrade data for 2021 (only export data of countries exporting to Albania is available) show that:

Albania imported dairy products for 47 m EUR in 2021, two thirds of this is for further processing by Albania’s dairy processing companies (60-80,000 t raw milk equivalent)

In terms of raw milk equivalents, milk powder and concentrated milk are the most important products which are imported (about 30,000 t raw milk equivalent) followed by whey powder and raw milk

Much of the milk powder and concentrated milk comes with very low percentages of fat (<1.5%); this means that imported milk is of low quality and needs added fat when being processed to ready dairy products – experts we spoke to assume that much of this is vegetable fat

Most of the milk powder, concentrated milk and whey powder is coming from Greece, while the top suppliers of fresh milk are Serbia (>6,000 t) and Italy (5,000 t)

With regards to technology and equipment, the larger processing companies are very competitive constantly improving the quality of their products. The most limiting factor to profitability is the shortage of raw milk. High prices paid for raw milk as well as the increased energy costs are currently putting a strain on the financial situation of processing companies.

When following a product along the dairy value chain (here examples of drinking milk and yoghurt), it becomes obvious that dairy processing companies in Albania are still quite profitable. They have an acceptable margin while the margin of farmers needs to be increased via better technology. Milk collection and distribution do not produce much margin; they are carried out by the processors with their own logistics to support the main business which is milk processing and the manufacturing of ready

dairy products. Retailers in Albania do not make much money. Unlike as in many other countries, their market power seems to be small due to low concentration and small quantities which each retailer trades.

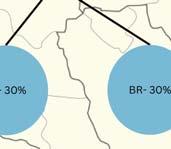

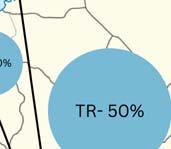

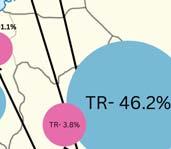

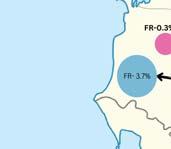

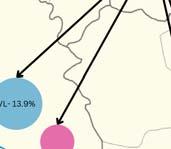

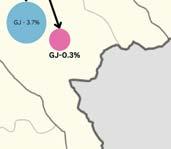

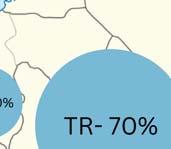

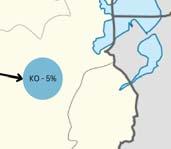

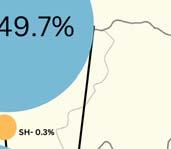

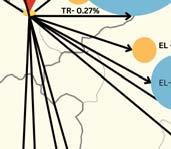

The survey with the 5 large dairy companies also clearly showed where most of the milk is coming from: >80% of cow milk processed in the dairy companies is coming from the Regions of Berat and Fier; 80% of sheep milk is from Southern Albania and 80% of goat milk from Northern Albania (Figure 5). Not surprisingly, Central Albania (with Tirana, Durres and Elbasan) constitutes by far the most important market for the 5 dairy processing companies (Figure 6, 79% measured in tons-of-milk equivalent for any

dairy product). The appendix contains detailed maps of the sourcing areas and the markets of each of the surveyed companies.

Source: Own calculations based on Donjaldo Hoxha (2022)

Source: Own calculations based on Donjaldo Hoxha (2022)

The difference between the figures of milk equivalent for dairy products delivered to market (Figure 6) and raw milk purchased from farmers (Figure 5) is remarkable. For the five surveyed companies it is about threefold and considerably higher than the figure of 60-80,000 t derived from statistics Be that as it may, the figures highlight the dependency of Albanian dairy processing companies on imports.

Most of the cow milk acquired by the surveyed processing companies is used for kackavall (yellow cheese) from cow milk (57%) followed by white cheese (21%) and yoghurt (11%). Only 10% is used to

produce drinking milk. Sheep milk goes into kackavall (69%) and white cheese (31%). The goat milk collected by the surveyed processing companies is used for white cheese only.

Interestingly, the processing into cheese does not bring the highest returns. The best margin is made from making yoghurt followed by drinking milk. White cheese brings more money than kackavall, although most milk goes into kackavall. This confirms what we see in dairy processing around the globe: The absorption capacity of the market for drinking milk and yoghurt is limited and the risk of spoilage high. Cheese like kackavall, however, stores well and this allows processing companies to accept lower margins. Figures 7 and 8 compare factory gate prices for raw milk with factory gate prices for ready products on the basis of kg of raw milk equivalent.

Source: Own calculations based on Donjaldo Hoxha (2022)

Factory

Source: Own calculations based on Donjaldo Hoxha (2022)

4. ANALYSIS OF BOTTLENECKS: FARM LEVEL 4.1 Genetics

The Holstein Friesian (HF) cow is popular in Albania and there are good reasons for this: It is worldwide the most widespread milk breed with enough genetic variety which gives ample opportunities to choose bulls for the individual breeding aim. HF cows in Albania have an average to slightly below average size And this results in the first problem: The cubicles in loose housing are too small. The same is true for the area per cow in stanchion-tied stables.

Cows have their origin most from animals imported from Czech Republic, Hungary or Germany years ago as pregnant heifers. Some farms are in the position to sell pregnant heifers from their own stock to other dairy farmers, but only very few. The quality of local stock is considered to be significantly inferior to that of imported heifers.

Some dairy farmers use sperm from meat breeds, especially Belgian Blue (BB). This seems to be a good choice, as milk yields are still satisfactory, but bull calves have a much better value.

It is still widespread that farms up to 50 cows use an own bull; however, the use of artificial insemination (AI) is more common. AI is carried out by the local veterinarian. Some larger farms have returned to bull services as results with AI have been disappointing.

The choice of bull is somewhat random. Not keeping any records of the individual milk yield, milk fat content and exterior features, the Albanian farmer is not in a position to make informed decisions about the most appropriate bull. This is definitely a problem that has to be dealt with. Once data is available, common methods of selecting the most appropriate bull (INET, TPI) can be used. However, without data, the only method that can be used is the aAa (or “Triple A”) method which entirely depends on an exterior assessment of the cow. This assessment is usually done by a specialised professional who is doing such assessments on a daily basis. Albania does not seem to have an aAa-specialist, but it would be worthwhile to train some so that farmers can already now – without milk yield, milk fat and milk protein data at hand – make basic breeding decisions: “Which cows should produce daughters for my future dairy herd (and be inseminated with an HF bull) and which cows should rather produce calves for fattening (and be inseminated with a BB bull)”.

The import of pregnant heifers from Central Europe is getting popular again. UN Comtrade data indicate that about 500 heifers are imported per year, mostly from Germany. One problem, however, which was raised was that of taxation: Breeding animals are considered agricultural inputs and should therefore not be taxed when imported in contrast to slaughter animals which are ordinarily taxed. To avoid that slaughter animal are imported as breeding animals, the practice in Albania is that the latter are taxed as slaughter animals when imported, and after several on-farm visits of tax inspectors following up on the fate of the breeding animal, the tax is then returned to the farmer after a year or so. This practice takes considerable cash out of the farm which is needed to support the breeding animals until calving. A policy recommendation should be formulated to stimulate heifer import.

4.2 Health

Visiting a farm is always a snapshot, but we saw no problems with lung disorders, skin disorders, snot in the noses or abscess. This is positive.

The main problems are: Mastitis, claw problems and problems with fertility. Mastitis has a direct effect on reducing milk yield. Without having done a thorough analysis of the root cause, we expect lack of hygiene and not well functioning milking machines to be major reasons. We got confirmation from farmers that they do not regularly (twice a year) control vacuum and pulsation of the milking machines. They also do not replace the nipple liners of the milking machines regularly.

Claw problems extremely affect animal welfare and lead to reduced milk yields as well as fertility problems. We saw many cows with claw problems. Good practice of trimming claws twice a year preventively is not applied. As this problem is acute, but at the same time not so difficult to resolve, we dedicate an own Chapter to claw trimming.

Problems with fertility: Data is not available to determine the scale of the problem. We estimate the average calving interval to be 382 days, but it could also be longer. Farmers and veterinarians report that the number of inseminations pro pregnancy is mostly larger than 2. Animal welfare and fertility are closely interconnected.

4.3 Claw care

This point needs quick and priority attention. In almost 80% of the visited farms we noticed no signs of claw care. We saw animals affected by mortellaro, a very painful infection of the skin between the claws. Preventive claw treatment together with disinfecting foot baths helps to prevent this and other claw diseases.

Farms with more than 50 cows often have a dedicated claw treatment box, but farmers lack the necessary experience of claw treatment Veterinarians we spoke to also have very little experience in claw care. In all Albania there seems to be only one person who offers professional specialised claw trimming services. We visited him and can confirm that he is doing a good job. However, there is room for many more well-trained claw trimmers knowing that experienced claw trimmers can do 6-10 cows per hour for preventive treatment, but need much longer per cow for curative treatment.

In Europe, claw trimming is usually not done by farmers or veterinarians, but by specialised service providers who undergo a special, but rather short training (4-5 weeks). They usually have a lot of experience and special equipment to immobilise the cows they treat. This allows for a high throughput.

It is also important for farmers to realise that the climate in the cowshed as well as the feed ration have an important influence on preventing claw diseases. A too high protein level in the feed ration, for example, is negative for claw health. On the other hand, there is evidence that sunflower oil seed cake makes the claws stronger.

4.4 Fertility and reproduction

We noticed that the success rate of artificial insemination (AI) was low: We met farmers who needed more than 3 inseminations per pregnancy (threshold should be no more than 1.8) resulting in high costs for semen and insemination services as well as an increase in the calving interval. Every extra day of the calving interval costs the farmer about 3 EUR/cow (loss in milk yield). When two extra inseminations are needed, the calving interval will be extended by 42 days which translates to a loss of 125 EUR/cow per lactation.

The reason for the long calving intervals is probably complex:

Farmers do not know the optimal time of insemination (which is about 10-12 hours after the cow shows signs of standing heat), they therefore do not alert the veterinarian in time. Farmers also do not inseminate themselves although this is good practice in farms in Europe with more than 50 cows.

In addition, there are fertility problems which arise from unbalanced feed rations, claw problems, mastitis and too high temperatures in the cowshed.

The veterinarian may not be very experienced in carrying out AI or in preparing the semen.

We also found that veterinarians do not use new methods of pregnancy control other than the rectal method which only allows for a pregnancy control from 7 weeks after insemination. Pregnancy scanners could determine much earlier if a cow is pregnant or not Such scanners are therefore instrumental in shortening calving intervals. A pregnancy test from 25-30 days after insemination should become an integral part of herd management.

Two thirds of visited farms use artificial insemination (AI) and one third the own bull. 3 farms have returned to bull services after making bad experiences with AI. In this way, they were able to decrease calving intervals

As a summary, there seems to be a general problem with fertility, but also with farmer skills to register heat and determine the right moment for insemination as well as skills of veterinarians to perform proper AI and early pregnancy controls.

4.5 Stable feeding Feeding roughage

In dairy cow production, roughage is the most important part of the feed ration: Up to 85% of a good feed ration should be roughage. In Albania, roughage is mostly made up of alfalfa hay in small or round bails and maize silage Popular is also the use of chopped wheat or barley (total plant silage). Residues of food manufacturing are also used by some: Brewers grain and 2nd grade carrots and potatoes

Growing conditions in Albania for the production of alfalfa seem to be very good. Even in years with dry summers famers can realise 4-5 cuts. In the Fier Region, alfalfa continues its growth in the winter period and can be fed fresh. With its deep roots, alfalfa is quite drought resistant and can be grown even without irrigation. The quality of the assessed alfalfa hay was from very good to poor (assessed by smell, number of leaves per stem and presence of mould). Protein is in the leaves, not in the stem. Here, training and sensitisation of farmers will be useful to help them improve productivity.

Maize silage is made from chopped maize mostly by a service company The quality of maize silage varied a lot among the visited farms (from very good to poor). Key factors are the right harvest moment

and correct chopping (each pit must be hit, so that the content becomes available for the cow) In addition, the process of making silage deserves attention. We saw a lot of damage of silage from holes in the plastic. Again, training might be helpful to let farmers understand the right moment and technique of harvesting as well as silage making

No farmer had an analysis of their roughage. This is a problem, because only with data for the energy and protein content of the roughage, an optimal feed ration can be composed. Feed rations need to be based on roughage and only supplemented by concentrate. Without an analysis of roughage, the effect of concentrate feed will be low as the total feed ration will then either have an energy or a protein surplus. Feed analysis therefore helps to reduce costs for concentrate feed.

Many farmers use a second-hand feed mixer. This provides the possibility to produce uniform feed rations. Most farms have sufficient roughage in store – enough for more than a year. The amount of available fodder therefore is not a limiting factor for increasing milk yields and for expanding the number of cows.

It is not a good practice to let the feed alley in the cowshed be empty between feeding times. We found often in day time no fodder in front of the cows. A principle in dairy feeding is to maximise fodder input, and empty feed alleys cost milk!

Metal detection

In Albania, the problem of fodder from the field being contaminated with metal residues (e.g. barbed wire, nails) seems to be acute. Almost all interviewed farmers have had some bad experience with pieces of iron in their fodder, particularly in alfalfa hay.

Most farmers apply measures against metal contamination: ►When using feed mixers, magnets are placed on the outfeed conveyor (however, this will not take out 100% of the metal in the fodder). ►Cows and young stock are made to swallow a magnet bolus into the reticulum. This costs some money, but is the best prevention against metal.

It has to be assessed whether farmers’ awareness of the problem of metal contamination and knowledge about appropriate measures is sufficient or whether a project intervention is worthwhile.

Feeding concentrates

We observed three different systems which farmers use:

1. Producing own concentrate from own wheat and maize and purchased soymeal as well as a premix (minerals, vitamins and amino acids) and then mixing all by their own

2. Purchasing all basic products (wheat, maize, soymeal, premix) and mixing by their own

3. Purchasing a ready concentrate delivered in bags of 25 kg (a few also get the concentrate in 1ton big bags)

Farmers buy basic products, ready concentrates and premixes from the following companies:

Vitalka: Produced in Croatia

Schaumann: Produced in Austria

Diamond V: Produced in USA

De Heus: Produced in Serbia (Dutch company)

Sano: Produced in Germany (only premixes)

Tecnozoo: Produced in Italy

Quantity is no problem: At the farms and at the distributors’ warehouses is enough in storage. However, the main issues are the following:

1. All companies offer feed ration advice for the farmers without having made any analysis of the farmer’s roughage available on the farm. Good advice cannot be given without analyses.

2. It appears that the purpose of the companies’ feeding advice is at times to sell as much concentrate as possible. We found feed rations with 70% alfalfa and 23% of soymeal. This results in an extreme protein surplus of the ration and is very costly for the farmer

3. The knowledge of farmers about the function of concentrate and premixes in the feed ration was found to me minimal. Also farmers were not sure how to adjust concentrate quantities to the phase of the cow’s lactation

As feed companies are in fierce competition to one another, it is recommended that those who want to stand out make analyses of the fodder resources available on the clients’ farms before advising on a feed ration. It needs to be in the interest of all (input providers, farmers, dairy companies) that feed cost are reduced and milk production optimised: More milk with lower costs

To lower costs for transportation and labour it is also recommended that ready concentrate is delivered onto the farm in bulk into silos. A truck would then just blow the concentrate into the silo.

To sum up: While usually enough roughage is produced (alfalfa hay, maize silage, total plant silage), quality varies enormously, and much can be linked to timing and knowledge. Large farms usually use second-hand feed mixers which is good practice. Simple principles, however, of offering roughage 24/7 and removing non-eaten remains twice a day are not respected. Imported concentrates, which push up the unit production costs, are not used rationally to complement own fodder, as farmers are unaware of the nutrient and energy requirements of cows and the amount of nutrients and energy already provided with the own fodder grown on-farm

4.6 Grazing

Grazing is not practiced among the surveyed farms. This is unfortunate as well-managed grazing is the cheapest system of feeding. It is also good for animal welfare and resistant claws. The reasons for the absence of grazing may be:

There is not enough land in family ownership and renting of land is based on too short terms for the investments needed to create a good pasture

For grazing, a maximum distance between cowshed and pasture should not exceed 500 m; there might not be enough available land in proximity to the farm

Grazing should take place on grass-clover mixtures, not on alfalfa; however, grass and clover need enough rain or irrigation, but available farm land may not have irrigation opportunities

Grazing is not part of the culture of Albanian crop farmers and they lack the necessary experience

However, in the Fier Region, it would make much sense for individual farms to consider developing a grazing system with strip grazing managed with the help of electric pasture fences. The area has available water for irrigation and to the West of Fier, land is abundantly available. It would be worthwhile supporting a pilot here.

4.7 Crop rotation

80% of surveyed dairy farms had land. Following a good crop rotation is essential for success in dairy production. Such a rotation should be based on the 3 main crops: alfalfa, maize and grains. When farms have to buy all fodder and feed it will be hard to withstand any price shocks as we saw them in 2022. At least alfalfa, but preferably, if machinery services in reach exist, also a large share of required maize and grains should be also grown on the farm.

A suitable 6-year crop rotation will be: 1) Alfalfa, 2) Alfalfa, 3) Alfalfa, 4) Maize, 5) Maize, 6) Barley. In combination with the available fresh or composted manure, yields in such a crop rotation should be high enough with little production costs.

During the survey, we did not study the farms’ arable production deep enough. However, a dairy development initiative will also need to assess farmers’ capacities to produce sufficient quality fodder and feed on the own land. This will include the question of fertilisation. Our first impression is that farmers do not take soil samples to devise a fertilisation plan In addition, they do not make optimal use of their own manure for cropping.

4.8 Mechanisation

Mechanisation is of great importance if dairy production should become attractive to the young generation and also to women.

Mechanisation of field work

While small 20-kg-bales of alfalfa hay are common, round bales with wrapping (producing alfalfa silage) are not heard of, but could help with improving fodder quality and reducing labour costs.

Small bales are still common in farms with about up to 100 cows. The baler is often owned by farmers, or small farmers use balers of their neighbours Small bales require a lot of labour, but are the only solution for farms with stables that have small doors. If workforce is available, small bales are a suitable system for small stables.

Increasingly, farmers make round bales with mostly second-hand round balers The average weight of these bales is 150-200 kg implying that for loading, moving and bringing them into the stable or the feed mixer, a tractor with front loader is required Round balers are used for alfalfa hay as well as straw from wheat, barley and oats.

It is recommended that farmers use round balers in combination with wrapping the bales with plastic In this way, the time of drying the cut alfalfa in the field can be greatly shortened improving quality, reducing losses from fallen leaves and making the fodder tastier. The result is a silage from alfalfa. In collaboration with a seller of agricultural machinery, such wrapper for round bales could be demonstrated at fairs and on open field days.

Making silage from maize or a grain crop requires much more investment into machinery. A forage harvester is needed to chop the crop into small pieces. Almost all farmers use a contractor operating a forage harvester when making silage. This is a good choice, as forage harvesters are expensive and need to harvest annually at least 800 ha to justify the investment. The farmer then compacts the material with a heavy tractor and covers it with plastic. It is important to protect this plastic either with soil or with a nylon protecting cloth to safeguard the plastic against birds and stray animal to avoid any hole in the plastic and damage to the silage. This was not seen on the surveyed farms. Field days during which

best practice of silage making is demonstrated to smaller and less experienced farmers are recommended in May/June when grain silage or August/September when maize silage is made.

Mechanisation of work in the stable

Fodder distribution in the stables also needs to be mechanised.

Farms with up to 50 cows usually distribute the fodder by hand. There is often no other choice due to low doors and narrow feeding alleys It was observed that the 2 main fodders, alfalfa and maize silage, are fed separately, alfalfa in the morning, maize silage in the evening. It is good practice, however, to feed a mix of both products at the same time. Maize silage as energy supplier and alfalfa as protein supplier then simultaneously enter the cows’ rumens. Besides this, farmers need to understand that dairy cows must have 24/7 available fresh fodder in front of them. Twice per day non-eaten remains need to be removed and given to dry cows and the older young stock. This will result into a higher feed intake and eventually more milk.

A suitable innovation for this type of farms are block dosing trolleys. They are rather cheap and small and have the ability to reduce handwork. They are not really feed mixers, but make fodder distribution easier. Second-hand block dosing trolleys are available for small money

Farms with more than 50 cows and stables with high doors and a feeding alley of a width of minimum 3.2 m are typically using feed mixers. We only saw second-hand machinery usually in a good state. The feed mixers used in Albania are all loaded by tractors with front loaders. Some had an integrated weighing system and some also integrated metal detection. Using a feed mixer has the following advantages:

Cows cannot select one fodder over another and each intake has the same composition

Calculated feed rations can be easily produced (therefore a weighing system is very important)

Mixed rations with some ingredients tastier and some less will lead to a higher feed intake

Time and effort for feeding is drastically reduced

Feeding could be reduced even to once a day (except for the warmer periods)

When selecting an appropriate feed mixer, the following points are very important: ►Adjustable counter blades (especially important when making mixes with straw and long alfalfa plants), ►Weighing system (for making mixes based on a calculated feed rations), ►Vertical mixers require less power and fuel compared to horizontal mixers, ►Loading system in the back if a tractor with front loader is not available. Farmers seeking second-hand machinery should especially look at the quality of blades and the condition of the bottom. Both should not be worn out.

4.9 Housing

Cows of herds up to 50 lie mostly on concrete, berths are generally too small, ventilation is missing and sick cows and those that are giving birth (3 weeks before and 3 weeks after calving) are not separated. There is neither enough natural nor artificial light in the stable.

When assessing housing, much has to do with cow comfort. During the survey, we used the Cow Comfort Index (CCI), which is a very simple method of assessing cow comfort and should be practiced by all dairy farmers and veterinarians. It measures the number of cows lying down and ruminating in their cubicles 2 hours before milking as compared to those standing (ignoring those feeding or drinking). Farmers should aim at a CCI of 85%.

Housing systems in Albania can be grouped into three categories: i) tied system, ii) loose housing in old stables and iii) loose housing in new stables.

Tied system

Farms in the survey with up to 50 cows use stanchion-tied stables: Cows are tied and feeding and cleaning is done by hand and milking with bucket milkers rolled from cow to cow. The floor on which the cows have to lie is mostly from concrete with no comfort. Stables have little ventilation as windows are small and mechanical ventilation is missing. Some farms have the possibility for free outside roaming in the day time, but there is no feeding place outside The quality of the milk and productivity are affected by a lack of hygiene, a poor climate and sub-optimal feed management

Simple improvements are possible: ►Put a layer from rubber or wood on top of the concrete; this lets cows lie more comfortably, ►For herds of 10-50 cows, a scraper could be installed which removes the manure automatically each half an hour, ►Ventilators will refresh the air in the stable, and ►Feeding place and watering devices outside when cows are on free roaming

Especially the rubber mat is an inexpensive and very effective investment. Simple rubber mats with an anti-slip profile (or a wooden covering) will bring huge improvements to cow comfort resulting into more milk by better and longer ruminating (cows ruminate when they lie), fewer claw problems, lower risk of abscesses and a better hygiene

Larger investments are needed when making structural changes to the stable. Many stables have mangers built at a certain height in front of the cows. However, when cows lie down and stand up, they need space in front of them. As the berth is only 2.0 meters long and cows cannot use the space in front of them because of the mangers, they lie down obliquely. This poses a risk to the tits of the neighbouring cows and prevents some cows in the row from lying down. It is highly recommended to remove the manger and construct a feeding alley which is only 10 cm higher than the berth

Loose housing

Farms with 30-100 cows typically use renovated old stables or self-made new stables made from second-hand materials trying to create loose housing with cubicles. Farmers usually know the requirements of modern loose housing systems, but are limited by the measures of existing buildings

A general observation is that the measures for the cubicles are too small, especially for HF cows. In addition, the cubicles are often made from concrete although wood or plastic would be much more comfortable for cows. Ventilation is deficient but could be easily improved with mechanical fans. What is also often missing are special areas for cows which are sick and those which give birth

Newly built farms with 100 cows and up use loose housing with cubicles, open side walls, a roof which is isolated against heat, scrapers for removing manure on a regular basis and floors with an antislip profile. This all corresponds to good practice. However, cubicles (2.0 x 1.1 m) are too small. In addition, a separate area for sick cows and those that give birth is hardly found.

In almost all visited farms, the berths give a very low level of cow comfort. A good berth will stimulate the cow to lie down and ruminate (70-80% of the time during the day). When the berth is too hard or to too cold, the cow will be standing too long becoming tired, ruminating less and putting a strain on the claws. In a loose system therefore the floor of the berth is important. One good example we saw was a farmer using sand with straw in the cubicles Mostly, however, we saw a concrete floor covered by a bit of straw or only concrete.

It is important to give those producers who intend to invest into new stables access to international consultants helping them in the design of the stable in order to avoid costly mistakes. It needs to be

noted that requirements in the coming years for animal welfare, health care, avoiding pollution with nitrogen, and protecting water sources will be increased along with EU approximation, and this needs to be taken into account already today when planning new stables. In addition, new stables need to have the possibility to expand into green energy production (solar and/or biogas). Respecting these requirements will make farms much more future proof.

To be very concrete: In the design of a loose housing stable with cubicles it is important that farmers make a strategic choice between two types of future-oriented designs: i) A deep litter cubicle (using straw, sand, peat, dried cow manure, sawdust, etc.) or ii) a cubicle covered with a rubber mat, a cow matrass or a waterbed. From the cow comfort point of view, both are good. The difference is the size of investment: Investment costs will be lower for the deep litter cubicles; however, annual costs will be higher for the litter as well as for the labour to replace the litter.

Housing for sick cows and cows before and after birth

All farms lacked a special area for sick cattle, cows with serious claw problems and cows for the period of 3 weeks before until 3 weeks after birth. Such animals need specific attention and therefore have to be separated. This space must be covered by straw and feed as well as water need to be abundantly available. If animals find shelter in these spaces, they will be relieved from competition with other cows and the risk of accidents and injuries will decrease.

Temperature and fresh air

In Albania, we estimate that 90% of cows supplying milk for dairy supply chains are housed in the stable for 365 days a year. Only about 10% are allowed some free roaming next to the stable between milking times. In view of the long and hot summers in Albania, a good ventilation system in the stables is a must for animal welfare and productivity reasons. Cows get less productive as soon as temperature goes beyond 22°C. Not only should ventilation reduce the temperature in the stable, but more importantly, it should allow for a good air circulation and remove the heat which cows produce. Ventilation in combination with a mister will produce cooling by evaporation. Open side walls and an open roof ridge are also important, and the roof needs to be insulated against heat.

Light

In virtually all visited stables the amount of light was not sufficient. The situation was even worse in the older and renovated stables which have only few openings in the side walls and mostly a closed roof ridge. In these stables farmers need to compensate the lack of light with artificial light which was highly inadequate especially in the autumn and winter. For a good fertility and productivity, a cow needs 16 hours of good light per day with a minimum of 150 lux LED lighting would be the best solution.

In fact, the doctrine in the time of communism which is reflected in the literature of that time was that artificial light in stables was not needed and that ammoniac in cow urine would destroy any electrical appliance in the stable. Recent research, however, confirmed the strong correlation between light on one hand and fertility and milk yield on the other.

4.10 Watering

Cows in loose housing usually get enough water. We saw good watering devices. Some, however, were placed such that they were at risk of being polluted by manure. A simple protocol for farmers to regularly clean the watering devices seems necessary.

A few farms let their cows go on free roaming between milking periods. We have not seen any watering tanks for them. Lack of water costs milk, but an investment into a water tank fixed on a trailer is very simple.

Cows in stables with a tied system work with 2 watering supply systems: A self-drinker per 2 cows, which is fine, or the farmer pours 3 times per day water into the trough; this is very bad practice as cows must have water available 24/7 for a good milk production.

No farmer had any idea about the water quality used as drinking water for their livestock. It is good practice to carry out a water analysis every 3-5 years. The dairy processors should deliver this service for their suppliers as they anyway need to regularly analyse the water they use in their factories.

4.11 Milking hygiene

As berths are usually dirty, also the tits of cows get dirty. Farmers then wet clean them and dry them with a cloth which is used for several cows and easily transfers bacteria. It is much better to have a system from the onset in which berths remain clean, either with rubber mats or by using plenty of straw or other litter (see Chapter on Housing). If wet cleaning is practiced, tits should be dried with disposable tissue paper. The milker is advised to use hygienic gloves in order not to transmit germs. However, we only saw on one farm that gloves are used. Tits are usually also not dipped to prevent mastitis.

In general, it was observed that the equipment was reasonable well cleaned – probably also because the processors usually sponsor the cleaning agents Those few stables with a milking parlour have an automatic cleaning system which if programmed well will ensure hygienic cleaning of all parts which come in contact with milk. Cleaning the milking parlour and the equipment after each milking with high pressure is necessary, and this was done correctly on the farms we visited Most cows, however, are milked with a mobile bucket system which is an inexpensive solution for smaller farms. Here, cleaning is not automated and requires observing standard procedures; especially the nipple cups must be brushed well We got the impression that farmers know the standard procedures well. They were probably trained by milk processors who also usually deliver the cleaning agents (acid and alkaline solutions). Empty cooling tanks have generally been cleaned well. However, the room containing the cooling tank was usually unacceptably dirty and this poses a risk of contamination.

As a conclusion, measures to improve milking hygiene should focus on improving the hygiene and health of the udder. Processing companies could, for example, support farmers by making available disposable tissue paper, dippers for treatment of tits as well as dipping liquid in order to protect the udder from infections after milking.

4.12 Rearing calves and heifers

We recorded very bad to average conditions for the rearing of calves. Not on one farm we saw optimal conditions of feeding, housing and treating calves. The igloo system which is now common practice for the rearing of calves in Europe could not be found.

A protocol for all aspects of calf rearing from birth to 8 months is very important. Part of this protocol will be a system to document calf development. Calves should be reared away from other cows. After 3 days they should receive good milk powder till around 8 weeks so that more milk can be sold to the processing company. Already after 1 week the calf should be animated to eat concentrate and fodder and to drink water

The age of first calving should be between 24 and 27 months. However, we did not see any heifer in that age which had already calved. This hints at a suboptimal body weight development of the young stock.

It is recommended to run a training course for dairy farmers on rearing of calves and heifers which includes all aspects of feeding, housing and animal health as well as criteria to correctly determine the moment of first insemination.

4.13 Herd management

Documentation for each cow does not exist among the surveyed farms – even not in hand writing. It is good practice and a precondition for proper management to register for every cow at least the date of birth, the start of the heat, the insemination moment, the chosen bull, the result of the pregnancy control, the starting date of the dry period, the use of medicines and treatments as well as the occurrence of claw problems and of mastitis. These data are all essential for the proper management of every individual cow

Beyond that for good breeding, data of the milk yield per cow, the fat and protein content of every cow’s milk and the results of exterior assessments are needed. Only then the right cows and bulls can be selected for the future composition of the herd. And only with this data, common methods of selecting the most appropriate bull (INET, TPI) can be used.

Documentation can be done with the help of a paper version using individual cow cards. For those who prefer to do this work on the mobile phone or the PC, a range of software is available. One of the simpler ones is Uniform Agri. When such software is introduced via training, veterinarians need to be involved because they will be among those who use the data.

For farms with a milking parlour, it is advised to invest in cow recognition by means of a sensor in a collar or in the ear. Milk data will then be automatically registered in a management system on the PC of the farmer (to which the data on birth, insemination, etc. need to be added). The bigger challenge, however, is to introduce documentation for those farms without a milking parlour.

Besides documentation, for good herd management, farmers and veterinarians require (re-) training in evaluating heifers for their readiness for first insemination as well as determining the right moment of insemination for heifers and cows.

4.14 Storage of slurry and manure

Slurry and manure have a value: They contain important nutrients for arable crops and bring organic matter on the fields. This stimulates soil life and humus creation. The value depends on the price of mineral fertilisers, but as a rule of thumb, the value of manure is minimum 30-40 EUR/t. A cow produces about 20 t of manure per year (i.e. 600 EUR) which is about 20% of the value of milk it produces.

On the surveyed farms, however, we noticed significant shortcomings in slurry and manure storage

Most slurry and manure is stored in a hole in the ground with no plastic sheets or concrete slabs protecting slurry and manure from leakages into the run-off or ground water. In addition, losses of nitrogen into the air occur in the form of ammonia. Farmers also do not compost their manure in order to make the resulting product stable and resistant to nutrient losses. In addition, farmers lack machinery such as manure spreaders or slurry tankers to get the manure into the field with little manual work.

At present we observe that farmers especially in Fier with its high greenhouse density sell their manure to greenhouse farmers for around 15 EUR/t undelivered and unloaded. This is where value is going down the drain.

Standard solutions need to be developed for farmers so that they know what to invest in. Farms with tied cows need a concrete slab for the straw manure and a tank in the cellar for the urine. Farms with loose housing produce slurry which is taken out by scrapers and should be stored next to the stable in basins made from thick plastic sheets. Necessary machinery includes tractors with front loaders, manure spreaders, slurry tankers and compost turners. Farmers must not necessarily own the machinery, but best use machinery services from within the area.

4.15 Access to finance for farmers

In most cases, investments were financed by remittances and contributions from family members. Bank loans were generally not used to finance investments. Of particular interest is some financing made available from processing companies to bind supplier closer to the company. Examples:

Providing cleaning agents for the milking machines and cooling tank

Installing a company-owned cooling tank on the farms of suppliers

Financing the purchase of pregnant heifers for the best managed farms among the suppliers (repayment in 3-4 years, based on a contract, via deductions from the milk price without any interest calculated)

IPARD grants did not play a role for the past investments of the surveyed farmers. With such grants, only new equipment can be financed. However, especially in dairy farming, there are ample opportunities for Albanian farmers to purchase good second-hand equipment (stable equipment and farm machinery).

5. ANALYSIS OF BOTTLENECKS: PROCESSOR LEVEL

5.1 Farmer-processor interface

The dairy processing companies do not differ much in processing standards and quality of output, but mostly in their ways of trying to support individual farmers in improving hygiene, milk quality and milk yield. This support consists of ►Free advice, ►Supply of free inputs (e.g. cleaning agents for the milking machine and the cooling tank), ►Lending of equipment (cooling tanks or second-hand chest freezers) as well as ►Financing for the purchase of imported pregnant heifers for the best managed farms among the suppliers (repayment in 3-4 years, based on a contract, via deductions from the milk price without any interest calculated)

After the milk is cooled down on the farm, milk transport is done usually once a day and carried out solely by the processing companies themselves. All companies use own transport for this. Milk collection centres are not used by the 5 visited processors; they prefer to take the milk directly from the farmers despite the often small quantities Only one of the 5 companies runs a milk collection centre for milk from small ruminants as the distance between production by smallholders and processing is more than 100 km.

At milk collection, the truck drivers usually take a milk sample which is later analysed in the company lab. These labs make a good impression. Some use fully automated and fast multi-parameter analyses. Of the 5 surveyed dairy processing companies, only one was not having an own lab. The lab situation is very different for small processors (baxhos) which usually do not have any lab, even not a field lab for instant tests. The company labs analyse milk for:

TPC (total place count, micro-biology, i.e. farm hygiene and milking hygiene)

SCC (somatic cells, i.e. udder health)

Antibiotics in the milk, which makes entire milk lots unusable for cheese making

pH, density and fat content, which indicate water addition

Lab results are usually not reflected in the milk price paid to the farmer. They are mostly used to safeguard the company against any fraud or negligence committed by farmers. All companies have a system in place which intensifies the sampling and testing for those suppliers with past histories.

The dairy processing companies claim that they use standards common the EU for the interpretation of lab results (TPC and SCC). However, the lack of milk on the market may put some pressure on processors not to enforce strict rules not to end up losing their suppliers who could easily go to less strict companies.

The milk price is generally calculated on the basis of quantity and fat content only while there seems to be zero tolerance with regards to antibiotics and dilution with water. However, until today the measurement of TPC and SCC does not seem to influence the price. This, however, provides wrong incentives to farmers TPC and SCC need to become integrated factors in the payment system.

5.2 Processing

Visiting the 5 selected dairy processing companies, we found in general a high and professional standard of management, hygiene, processing equipment and laboratories. In the past 10 years, the larger processing companies (IPQ members) have made significant investments in facilities and equipment.

In another assignment, 7 smaller dairy processing enterprises (“baxhos”) were visited in December 2022. Although they usually also operate according to standard operational procedures of the dairy industry, it was found that many of them need to invest into improving elements of the buildings which are used to shelter the processing units Typical shortcomings refer to:

No documented food safety system

The building’s ceilings, lighting and protection of lamps against breaking of bulbs

Floor drainage and unsmooth joints between walls and floors and

Insufficient sinks in the processing areas, lacking dressing rooms and improper toilets

Lacking protection of windows and doors against flies and rodents

Missing facilities (e.g. tanks) for wastewater collection and treatment

Milk processing is energy intensive, and in the current situation of high energy prices, some companies are getting cash flow problems Only one of the surveyed five larger processing companies has PV panels on the roof of its facility which produce about 15% of the required total electricity. Another company is planning to build a new facility which will also be equipped with PV panels on the roof. Solar electricity generation for own consumption will certainly strengthen the financial position of milk processors. Even systems without battery may help as much of the energy is needed during day time.

5.3 Competitiveness

Raw milk scarcity in Albania, high prices for raw milk on the European market as well as increased energy costs have reduced the competitiveness of Albanian dairy processing companies in the regional and the Albanian market compared to those from neighbouring and EU countries Through their association IPQ, dairy processing companies are repeatedly calling for:

Subsidies for farmers via direct support per litre of milk delivered to licensed processing units, direct support per each head of milking cow, sheep and goat as well as direct support per hectare of land used for the production of animal feed and fodder

Lowering the VAT on sales of dairy products on the Albanian market (call for 6%) as the current VAT rate on dairy products is higher than in other countries of the region

Removal of the gas excise for the milk processing industry

Improvement of the legal framework to facilitate Albanian exports of the dairy products into CEFTA countries

Another point which IPQ members (who are the larger companies among milk processing enterprises in Albania) advocate for is for government to take action against informal operators in dairy processing as they create “unfair competition”. It is argued that actors from the informal sector sell raw milk directly to consumers without pasteurisation which poses a risk of food safety

6. CONCLUSIONS

Activities to strengthen the dairy supply chain needs to be measured against the following 3 objectives:

1. To increase the amount of milk by improving the production per cow and the amount of cows

2. To increase milk quality at farm-level

3. To decrease the production cost for milk at farm level

Much attention needs to be dedicated to capacity building at the level of farmers and veterinarians. If this does not happen, investments done by farmers from remittances or family members, or financed by processing companies or the public grants risk of being underexploited. In the short-term, capacity building is necessary in the following spheres all of which are crucial for dairy production:

1. Calculating appropriate feed rations based on analysed fodder samples and improving the quality of fodder that is growing on the own farm

2. Introducing a herd management system for every dairy farm which includes keeping records for each cow to provide data needed by farmers and veterinarians to improve productivity

3. Improving stable conditions to enhance animal welfare which is the basis for good milk yields as well as labour productivity (most important aspects: Size and floor of berths, lighting, ventilation, cleanness, milking hygiene and opportunity for mechanisation)

4. Improving insemination decisions by training farmers and veterinarians in body scoring, determining the optimal moment for AI as well as pregnancy control

5. Improving claw health as one of the most important factors affecting milk yield and fertility by facilitating the set-up of specialised claw trimming services

At the level of processors, it is important to sensitise companies for a change of the milk payment system: Farm and milking hygiene as well as animal health need to be rewarded via a quality-based milk payment system which builds on the regular analysis of TPC (indicator of hygiene) and SCC (mastitis as an indicator of animal health) in the milk collected from farmers.

Capacity building must involve not only farmers and veterinarians, but should be extended to students of the Fier Professional School, too, as well as to students of institutions of tertiary education. Much of the best practice on which this report is based has been developed over generations in Central Europe. As part of capacity building therefore, an internship scheme for young professionals from Albania on farms for example in Switzerland seems to be helpful: Young dairy farmers, sons and daughters of dairy farmers in education, dairy farm workers as well as dairy farm managers should receive the opportunity to learn and exercise best practices through internships

In addition to capacitybuilding, we also need to stimulate investment, for example into new cow stables or the reconstruction of old stables into units which respect the basic principles of animal welfare. For the dominant types of stables (tied system, loose housing in renovated cooperative stables and loose housing in newly built stables) we need standard improvements which can be implemented by farmers with little costs. Investment stimulation is also required for farm machinery allowing farmers to make better use of the roughage grown on the farm as well as the manure produced in the stable with the limited labour resources famers have.

Only with such investments, it is worthwhile for farmers to increase the size of their herd, for example by importing pregnant heifers from Central Europe.