5 minute read

Lessons From the 1918 Spanish Flu Pandemic

from The Link, Issue 34

by The AHLC

We didn’t learn the lessons of the Spanish Flu pandemic, and there is a reason.

In times of upheaval, we often turn to history for a guide to what the future holds.

caused by the coronavirus, the so-called Spanish Influenza pandemic of 1918-19 offers us a window of what could come in the months and years ahead because the scant lessons learned at the time were quickly thrown by the wayside.

With the world in the grips of World War I and thousands of American men being drafted into the military, it’s not surprising the U.S. government didn’t broadcast the fact that the flu likely would claim hundreds of thousands American lives. After all, it was a time before instant communication, before 24-hour cable news cycles, and before the internet.

The only way the world became aware of the full scope of the pandemic was through Spanish media. The country was neutral during the war and free of government news censorship. That’s why is called the KELLY CARSON

In the case of COVID-19, the disease

AHLC Editorial Consultant, The Link Magazine Spanish Influenza, and not, say, the Kansas Flu, where it is believed to have started.

Governments and media in the United States purposely misled Americans about the impact of the pandemic because the nation was at war. There was enough fear to go around without exacerbating it with a deadly flu.

John M. Barry, author of “The Great Influenza: the Story of the Deadliest Pandemic In History,” said in a recent Yahoo News article that the federal government had no plan to deal with the pandemic and instead pushed a story of calm and comfort.

“Some of them told outright lies, some of them simply misled,” Barry said in the March 6 interview. “As a general rule, there were very misleading statements in an effort to reassure. The Chicago public health director said, ‘Nothing is done to interfere with the morale of the community.’ And what that meant was, basically he lied every time he made a statement.”

The first wave in 1918 wasn’t particularly deadly, though thousands lost their lives.

“World War I was not only costly, it required much of the medical community to be stationed overseas. In 1918, little was known about influenza. While this lack of knowledge did not negatively impact infection control actions, effective treatment and prevention methods were not fully utilized.”Miles Ott, Shelly F. Shaw, Richard N. Danila and Dr. Ruth Lynfield wrote in their 2007 report “Lessons Learned from the 1918–1919 Influenza Pandemic in Minneapolis and St. Paul, Minnesota,” published by the U.S. National Library of Medicine National Institute of Health.

When the war ended Nov. 11, 1918, cities around the country hosted victory parades and celebrations. People threw off the shackles of the war days and partied with abandon.

But then the second wave came in 1919.

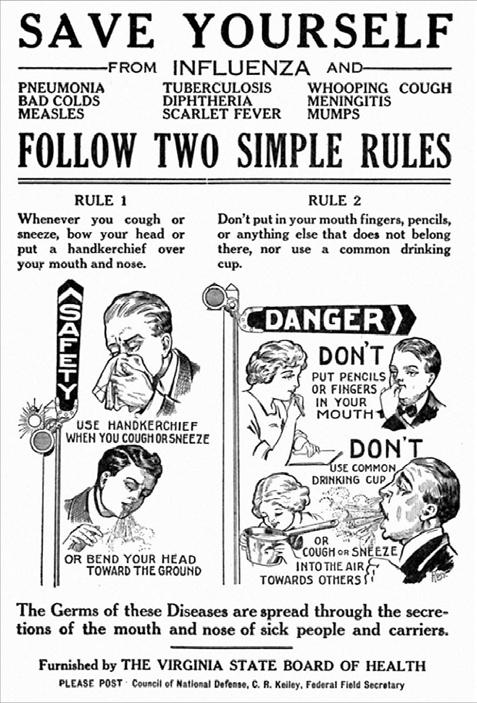

“Coordination between different levels and branches of government, improved communications regarding the spread of influenza, hospital surge capacity, mass dispensing of vaccines, guidelines for infection control, containment measures including case isolation and closures of public places, and disease surveillance were all employed with varying degrees of success,” the scientists wrote in their 2007 report.

Mitigation efforts proved too little, too late. Hundreds of thousands of people would die by the time the flu began to wane in 1920.

So why didn’t we know more about the Spanish Flu before COVID-19 took over the headlines?

As Lauren Spinney wrote in her 2017 “Pale Rider: The Spanish Flew of 1918 and How it Changed the World,” “grief and recovery were often private.”

“The Spanish Flu is remembered personally, not collectively,” Spinney wrote.

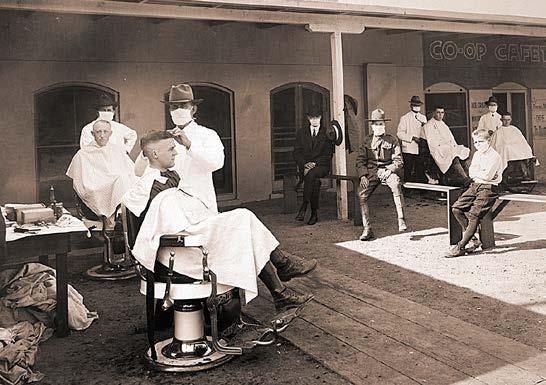

Our national archives are filled with photographs of masked Americans trying to lead normal lives during the pandemic, but social mores of the day often dictated that people didn’t discuss their illness in polite company.

In her 2012 book “Envisioning Disease, Gender, and War: Women’s Narratives of the 1918 Influenza Pandemic,” author Jane Elizabeth Fisher suggests the country’s failure to respond to the flu might be attributed to a general weariness of death.

“The silence surrounding the 1918 influenza pandemic can also be interpreted as a kind of tribute to its awe-inspiring destructive power, the terrifying number of people it killed, and the inability of human language to adequately represent mortality on such a large scale.”

In a Slate interview published May 2, author Rebecca Onion and scholar Elizabeth Outka take a look at why the 1918-19 pandemic was mostly overlooked in our collectively history.

“Diseases are recorded differently by our minds than something like a war,” Outka says in the interview. “By their nature, diseases are highly individual. Even in a pandemic situation, you’re fighting your own internal battle with the virus, and it’s individual to you. Many, many people in a pandemic situation may be fighting that same battle, but it’s strangely both individualized and widespread.

“A pandemic’s enormous impact is just not necessarily one that’s recorded in the ways we expect history to be recorded. You can record the economic loss; you can count the bodies — though that can be difficult, too. You can study the science of

the virus, but there’s a difficulty with making the loss visible,” she says.

“Of course, that’s one of the reasons we have memorials to people who died in wars — to take something not quite tangible and turn it into something people can see. I think with diseases, that can be difficult to do,” Outka says. “Diseases often impact bodies in ways that are difficult to define. Viruses are invisible, contagion can often be tracked generally but not specifically. I think these are all things that feed into this.”