9 minute read

DESIGN SPACE

Grow Your Own, Dammit!

BY SCOTT ELLIS, ED.D.

Advertisement

In the economic climate of 2021, it is very difficult to attract, engage, and retain people who are willing to work and capable of exercising good judgment. Blame a past or present administration, or the pandemic, or “kids these days” all you like. But please, stop complaining that you “can’t find good people” if your primary source of candidates is still the temp agency.

Modern workforce development requires that your company invest in education and skills training locally so that the workers of the future will be prepared to thrive in your employ. It also requires that we invest in current team members to develop their critical-thinking skills. They can be engaged by involvement in problem-solving, planning, and implementation of ongoing improvement, growing their skills in judgment with each experience.

Lessons in judgment came hard and early for me. My grandfather was a cop, a farmer, and a teacher of life lessons. My lessons were as constant as required by my creative disobedience and general immaturity. When I was a boy of 8 summers, my chores included the feeding and medication of a bull calf. All summer, I would rise before sunrise to rope the calf for medication and bottle feeding. It was complicated by the fact that 8-week-old calves outweigh 8-year-old boys. He did not enjoy being roped before breakfast, particularly when the meal included a hot-dog-sized pill to treat scours (that’s bovine for diarrhea).

One morning I was having a particularly rough time. The Guernsey bull calf had been roped easily enough but had no interest in being tied to the center post. He had dragged me through the slime and knocked me into the fence. I snagged the rope, planted my feet, and thought of the most potent swear word I knew. Throwing my weight toward the center pole, I commanded, “Come here, dammit.” I looped and tied the rope neatly to the pole and stood back to survey my solitary victory. “Is that the calf’s name?” asked a deep voice behind me. How did he do that? He was always just there. “No sir,” I replied in a hushed tone. “It is now,” he said, and he went about his work.

I didn’t hear another word about it until the family had finished Sunday dinner. Then it happened; he removed his toothpick, leaned back in his chair and donned a puzzled look. “Now Scotsman, what was that calf’s name again?” I glanced at my grandmother and my mother and said, “Uhhh, Dammit, sir.” We repeated this ritual every Sunday until that wretched animal took his rightful place in the meat locker.

My grandfather consistently used logical consequences to guide me toward maturity. He also allowed natural consequences to teach me, but those lessons quickly grew more severe. He took me along so that I could observe, and he allowed me to ask questions so I could understand the choices he made. When we worked together, he would ask me, “What comes next?” in order to engage my head and my hands. By thinking out loud through planning and problem-solving on the ranch, he taught me skills that transferred to every aspect of life. His example has been my model for helping employees learn problem-solving skills for today while developing critical thinking for tomorrow.

Test me in this. Use the time that is already set aside for crew meetings to engage them in a discussion. Say there was a quality snafu last week that made it to your customer. It would be easy, even natural, to vent frustration toward the crew—to sit them down and tell them the cause of the problem, the solution, the standard of performance, and the consequences of failure to meet that standard. But this will not change future outcomes or their ability to improve them. Assigning blame sucks all the energy out of improvement. What if, instead, the meeting began with everyone getting on one side of the problem? “Folks, we let our customer down last week, and we need to work together to fix our process. The way we are doing things today allowed this production loss to hurt our customer. I need your help in closing the gaps in our process so this cannot happen again.” With the focus shifted to what happened, rather than who did it, you can attack the problem together.

Although it is likely that you knew the root cause when you entered the room, there is value in examining the noncompliant product and discussing all the possible causes, perhaps using a fishbone diagram. The team develops a better understanding of the causes and then focuses on prevention. Keep asking the question of your team, “How can we make it difficult to do this wrong?” By this method you may grow your own willing and capable employees.

Scott Ellis, Ed.D.,

delivers training, coaching, and resources that develop the ability to eliminate obstacles and sustain more effective and profitable results. He recently published Dammit, Learning Judgment Through Experience. His books and process improvement resources are available at workingwell.bz. AICC members enjoy a 20% discount code: AICC21.

Design Adapts and Grows

BY BRIAN VITAGLIANO

As anyone who has ever worked in a design department can attest, design changes are commonplace. The design sector of the corrugated conversion industry is no different. These days, the design environment itself appears to be going through a major revision of its own, with changes hitting all aspects of this sector of the industry.

Though my perspective on this will be influenced greatly by my personal experiences over my first decade in this industry, there are many trends that will be recognizable to anyone in the corrugated industry who is working either in or closely with design. From what is being designed to how those designs are being created and communicated, we have seen rapid developments across the design space. But with a new crop of informed designers coming into the fray, the sector is well positioned to facilitate this quickly evolving landscape.

“Nobody intends to get into this industry; you are either born into it or you accidentally fall into it and never leave.” I’ve heard sayings to that effect many times since I myself fell into the corrugated industry. Back in 2011–2012, I had recently graduated from college with a degree in architecture, with no strong desire to be an architect—not unrelated to the fact that job openings in architecture were a rarity following the bursting of the housing bubble. I answered a job posting that I believed at the time to be a graphic design position, only to show up to the interview and find that the job I had actually applied for was that of a structural designer in a corrugated sheet plant. I knew nothing of the corrugated industry; I definitely didn’t know the first thing about corrugated structural design. But thankfully, their desire to pay as little as possible aligned perfectly with my lack of experience—as well as piquing my curiosity based on what I learned in that interview.

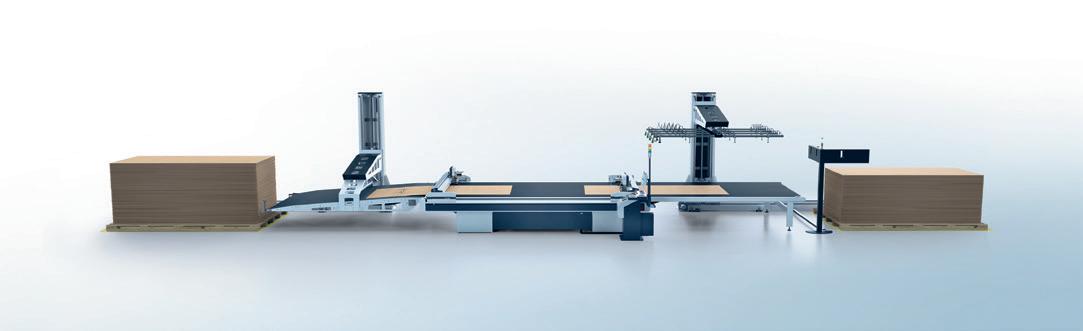

Digital cutting at an industrial level.

1.5 AD Zund 1m

Contact us anytime for a personal demo, and see Zund at SuperCorrExpo Booth 2355

Over the next few years, I learned a lot. It was a trial by fire, and the teaching I received came from either someone who was born into the industry or who unintentionally stumbled into the thick of it, just as I had. But that is changing rapidly. I have a structural designer in my department who had every intention of pursuing a career in corrugated structural design, learning software and basic concepts back in college. Similarly, when my department’s graphic designer showed up for her first day all brighteyed and bushy-tailed, she already had a personal copy of the Fibre Box Handbook. More and more I am hearing about new programs in colleges that directly relate to this industry, and I am meeting more and more young people who are not only aware of the industry but are seeking to start careers here. For someone like me—who lucked out by stumbling blindly into the corrugated world that I now call home—this is an exciting change to see!

Trigger warning: Although I would have loved to avoid any discussion around COVID-19, the realities of this current pandemic environment have accelerated many of the other changes we are currently seeing in the design sector. From the types of projects that are requested to the way those projects are communicated and, ultimately,

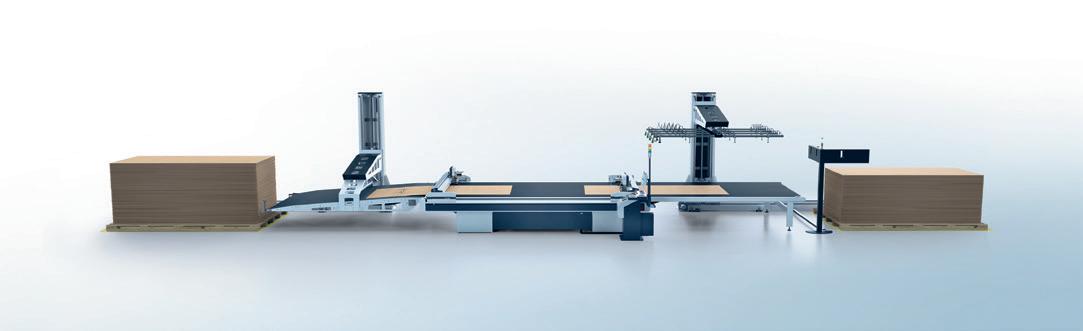

The Board Handling System BHS150.

AD

Zund 2

infous@zund.com T: 414-433-0700 www.zund.com

to how the design of those projects is approached, this social distancing climate has led to changes in each step of the design process. Case in point: Online shopping was already growing at a rapid pace, but social distancing and temporary store closures led to an explosive boom in e-commerce and direct-ship product deliveries. Although retail packaging and displays are still encountered, shipping boxes and direct mail pieces have grown greatly in importance. Similarly, where most meetings used to happen face to face, it is much more common to work based on information obtained solely through email or phone calls. In some ways, this has upped the amount of direct communication from the customer to the designer, as digital communication can be both initiated and relayed quickly and accurately.

As far as the actual act of designing is concerned, digital technology solutions have grown greatly in importance. Though 3D CAD solutions were not uncommon pre-pandemic, the need to design within a digital 3D environment expands greatly when access to a cutting table—or material for that cutting table— is limited. Similarly, when working within a digital 3D environment, a digital show-and-tell creates rapid communication of those ideas with a customer before a physical sample needs to be cut and delivered.

Though change is common in any design environment, the rapid change currently being experienced in the corrugated industry is notable. Hastened by the current social distancing environment, most every aspect of design has seen rapid advancement in the past year. The value of digital mediums of communication and design has not only increased but also found ways to better work in conjunction with the basic building blocks of designing in this industry.

Samples still need to be cut, and faceto-face meetings still need to happen. But the efficiency surrounding these actions has increased greatly. With an incoming design workforce that is not only more acquainted with current technologies but more familiar with the industry at large, the design sector will continue to grow and adapt quickly alongside a workforce that is able to move in lockstep with this rapidly changing design environment.

Brian Vitagliano is design manager at Tavens Packaging & Display Solutions. He can be reached at bvitagliano@ tavens.com.