5 minute read

Book Review

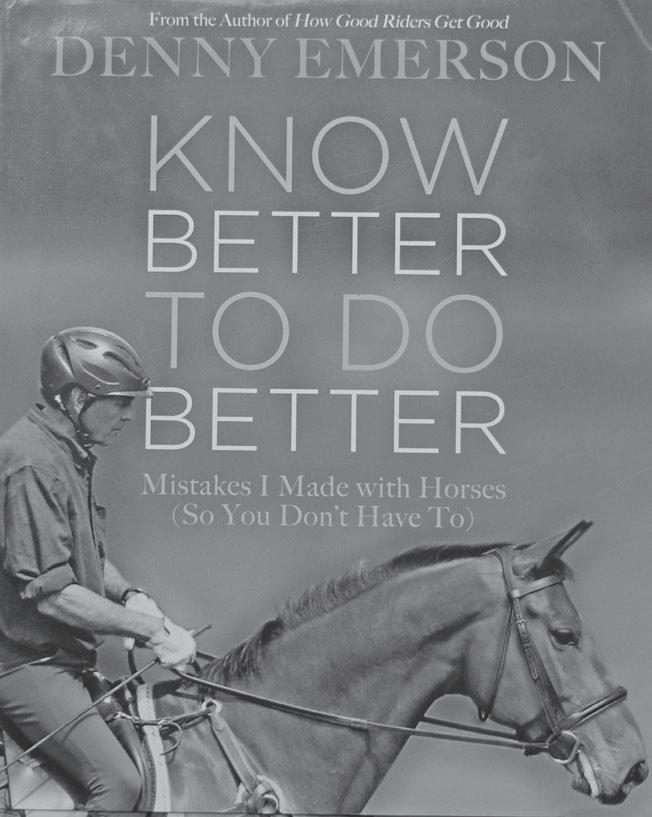

Book Review Know Better to Do Better

Mistakes I made with horses so you don’t have to

Advertisement

By Denny Emerson

Trafalgar Square Press North Pomfret, Vermont. 2019.

234 pages, illustrated. $29.95 Hardback. $11.99 Kindle.

Reviewed by Pam Gleason

If you have ever thought it would be interesting to sit down with an “old-time” horseman and have a wide ranging discussion about riding and training, then Denny Emerson’s latest book should be in your library. Know Better to Do Better purports to be a book about Emerson’s equestrian education, in which he shares mistakes he made along the way so that “you don’t have to.”

But the book is really much more than that. As a sequel, of sorts, to his earlier title How Good Riders Get Good, it takes the reader on Emerson’s own personal journey, showing how a horse crazy kid transformed himself into an Olympic three day event rider, as well as a champion endurance rider. Part memoir, part history and part howto, the book is told in an engaging and conversational style that allows Emerson’s dry humor and no-nonsense philosophy to shine through. Although in some places (especially the first chapters), Emerson seems to be trying to address beginning riders, this is really a book tailored to people who are already horsemen, and want to be better at it. Emerson himself describes it as a “toolbox of ideas that a reader can refer to when in need of solutions or ideas, sort of the way people have cookbooks in their kitchens.”

Denny Emerson was born in 1941 and grew up in western Massachusetts and Vermont. Starting out as a backyard rider on his trusty pony Paint, he says he learned about horses by watching cowboy movies, and absorbing information as a “barn rat” in the stables at Stoneleigh-Prospect Hill School in Greenfield, Massachusetts, where his father was headmaster. But from the beginning, he was ambitious. At 13, he read an article about the 100-mile endurance ride at the Green Mountain Horse Association in Vermont, and was inspired. So over the next year, he conditioned his new horse, Bonfire, to compete in the race and completed it when he was just 15.

Shortly afterwards, his riding career shifted to saddleseat riding on Morgan horses. Everything changed again in 1961 when he drove down to South Hamilton, Mass. to watch the Wofford Cup, his first three day event. Knowing this was the sport for him, he then taught himself eventing. Within a little more than a decade, he was named the United States Eventing Association Rider of the Year. In 1974, he helped the United States win team gold at the World Championships at Burghley in England, jumping double clear on his gelding Victor Dakin.

Emerson’s eventing career included 29 years of riding at the Advanced level, as well as 50 consecutive seasons of competing at Preliminary or above. He has trained and campaigned 14 horses to Advanced, and is the only rider to have won a world championship in eventing and to have completed the 100-mile Tevis Cup endurance race. Still riding and training today as he approaches 80, he certainly has a wealth of experience. In this book, which is more a smorgasbord than cookbook, he shares plenty of practical advice with readers, along with anecdotes about various horses he has owned or known through the years.

Certain themes stand out. Emerson’s own career is a testament to fact that if you want to do something in the horse world, jumping in with both feet is a good way to go, and he is impatient with people who make excuses. “Forever I listen to people talking and lamenting about how they ‘want to do this,’ ‘hope to do that,’ ‘wish to do the other,’ never managing to commit themselves to taking that critical first step. . . . . If I could advise only one thing in this entire book, it would be something I figured out for myself. ‘Take the first step.’” He writes.

When it comes to things that he had wished he had done better with horses that he owned, the overriding theme is that, if he could do it again, he would take more time and be more sensitive to them. With Cat, the horse on which he did his first long-form three day event, he wished he had worked harder to gain the horse’s trust. “I would do groundwork, I would do lots of walking under saddle. I would try to get him to stretch, to gently bend, to get him over the idea that a human was an adversary.” With Victor Dakin, the horse he rode to victory at Burghley, he says he wished he had recognized that the horse’s persistent difficulties in dressage stemmed from fear. If he could do it over again, he would have tried “all sorts of strategies to try to win his confidence and alleviate his almost claustrophobic fear of being placed between the driving aids and the restraining aids.”

Other main points include the importance of fitness for both horse and rider, and recognizing that most people expect too much out of each training session. “When training horses, ‘pretty good’ needs to be seen as ‘good’ and ‘quit while you’re ahead should be everyone’s motto.” Emerson is a believer in patience, consistency and hard work. When it comes to horse training, he is also a big believer in walking to condition the horse and to establish and develop the horse and rider relationship.

Finally, although a certain amount of arrogance certainly propelled Emerson’s own career, he recognizes and celebrates the importance of humility, and of learning from mistakes, both your own and other people’s.

“I look back at pictures from the 1960s and 1970s. . . when I thought I had a clue, and I know beyond a shadow of a doubt that much of what I thought then was not only wrong, it was based on bad horsemanship . . if you are unwilling to accept that you can change and learn and grow, if you are too arrogant, too sure that what you think is right just because you think it, you will probably stay inept and incompetent,” he writes. But he ends the book with the caveat that looking back and saying “I wish I had known then what I know now,” should be an optimistic statement, because it shows how much you can improve.

“If I were to rewrite this book some years from now, I hope that I’d need to rewrite it because I would have kept on learning better ways. That’s why I won’t conclude with ‘The End.’” He writes. “These two words presume that my learning is over, but tomorrow I’ll climb on some horse who will show me I’ve still got lots to learn.”