THE NEED & NECESSITY FOR ADAPTIVE RE-USE OF STEPWELLS & TEMPLE TANKS IN INDIA

A DISSERTATION REPORT

Submitted by AISHWARYA SREEKANTH

Under the guidance of AR. AJIT KAVIN

in partial fulfilment for the award of the degree of B. ARCH.

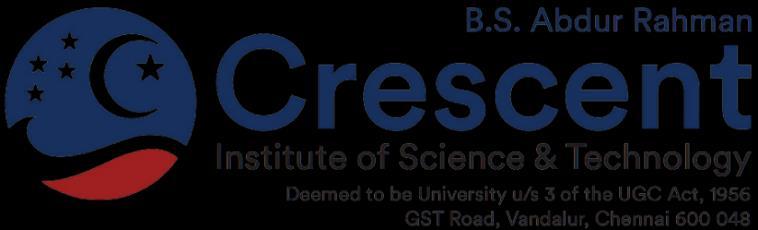

CRESCENT SCHOOL OF ARCHITECTURE

B S ABDUR RAHMAN CRESCENT INSTITUTE OF SCIENCE & TECHNOLOGY

CHENNAI – 600048

NOVEMBER 2022

BONAFIDE CERTIFICATE

Certified that this dissertation report ‘The Need & Necessity for Adaptive Re-use of Stepwells & Temple Tanks in India’ is the Bonafide work of AISHWARYA SREEKANTH (RRN: 180101601003) who carried out the dissertation work under my supervision. Certified further, that to the best of my knowledge the work reported herein does not form part of any other thesis report or dissertation based on which a degree or award was conferred on an earlier occasion on this or any other candidate.

SIGNATURE

AR. AJIT KAVIN

SUPERVISOR

SIGNATURE

PROF. G. JAYALAKSHMI

DEAN OF THE DEPARTMENT

Assistant Professor Professor & Dean

Crescent School of Architecture

B.S. Abdur Rahman University

Vandalur, Chennai – 600 048

Crescent School of Architecture

B.S. Abdur Rahman University

Vandalur, Chennai – 600 048

SIGNATURE

EXTERNAL EXAMINER

2

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

I extend my heartfelt thanks to our Dean, Prof. G JAYALAKSHMI, Crescent School of Architecture, for accepting the study topic. I extend my sincere gratitude to the internal review panel members, Ar. AJIT KAVIN, (Assistant Professor, Crescent School of Architecture) & Ar. RAGAVI (Assistant Professor, Crescent School of Architecture), for their constructive criticism, that really helped me improve & take this report to the next level.

I am very indebted to my guide, Ar. AJIT KAVIN (Assistant Professor, Crescent School of Architecture), for his consistent support and encouragement and for his endless patience throughout. Without his continuous guidance & support, this report would not have been possible. I also express my sincere thanks to the internal coordinator, Ar. RAGAVI (Assistant Professor, Crescent School of Architecture), for her constant guidance and supervision during my dissertation.

I am thankful to my family and friends for their encouragement and support during my dissertation process.

3

ABSTRACT

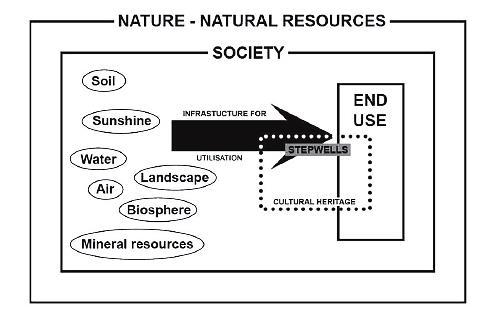

The role of ‘Water’, as an element of nature, plays an important role in Hinduism – it has sustainable usage in Ritualistic Ceremonies, serving as a means of Worship, in the form of Neer Prasad. The essence that ‘Water’ creates in the practice of Hinduism, can be found in the Stepwells & Temple Tanks of India – where water bodies are given elevated importance. Originally, these tanks were meant as a place of ritual cleansing, by the means of washing hands and feet or performing ritual bathes. On that note, the usage of Temple Tanks has grown towards being an Urban System, leaving out the benefits of recreation.

The core concern of the infamous Hindu ritualism is concerned with the manipulation and maintenance of purity and impurity. Purity is increased by associating or coming into contact with things and actors assigned pure status and by reducing association with things and actors of impure status. There are essentially two ways to bring about a condition of purity, one is to distance oneself from objects signifying impurity and the other is to purify oneself by things recognized to have the ability to absorb and thus remove pollution directly. Water is the most common medium of purification. It is considered to have an intrinsic purity and the capacity to absorb pollution and carry it away to unfold the context of social stratification in Indian Hindu society and to determine the role of water in the regulation of social order it is essential to go back into history to trace the origin of the institution of these belief systems and forward into existing social and cultural contexts

As empires and communities evolved in ancient India, purpose of these public spaces grows in relevance to the needs of the people; in the Northern Region of India – where Temple Tanks evolved to become Stepwells Stepwells created a zone of interaction and community, unlike Temple Tanks, that particularly served as ritual grounds for the religious. In today’s society, these architectural marvels have a scope to serve as more than just a means of Water Conservation, or a ground for ritualistic practices.

4

5 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction Aim 6 Research Question 6 Significance of Study 6 Hypothesis 6 Objectives 6 Research Methodology 7 Scope & Limitations 8 Background 9 Chapter 1: Introduction to Study Importance of Water 11 Relationship between City & Water 12 Chapter 2: Background & Context History 12 Evolution 13 Typology 15 Chapter 3: Traditional Water Harvesting Systems (TWHS) Stepwell – Chand Baori 18 Temple Tank – Kapaleeshwarar Theppakulam 19 Chapter 4: Comparative Study Culture + People 20 Usage + Functionality 23 Material + Construction 27 Preservation of Architectural History 28 Chapter 5: Need for Adaptive Re-use: Stepwells & Temple Tanks Today’s Scenario: Declination & Revival 31 Strategies for Adaptive Re-Use 32 Conclusion 37 Appendix Glossary 40 Interviewee Biography 42 Bibliography 43 References 43 List of Figures 44 List of Tables 47

I. Aim

This dissertation research is an attempt on exploring the necessity of conserving Stepwells and Temple Tanks of India, investigating its preliminary Usage & Functionality, leading towards the development and impact these Water Reservoirs create in the current Urban Context of India.

II. Research Question

Considering the historical and present relationship between ‘City & Water’ in India, to what extent is there a need for the Adaptive Re-use of Stepwells & Temple Tanks, in the near future?

III. Significance of Study

The study focuses on the need to conserve Stepwells and Temple Tanks in India, to overtake the harmful impacts made through contemporary or urban infrastructures. The significance of this study lies in its intention of relooking at current usages and functionalities of Stepwells and Temple Tanks in India: aiming to rebuilt the cultural context, connection & improve Climatic context with these Traditional Water Reservoirs.

IV. Hypothesis

Every Stepwell and Temple Tank of India serves a major role in a communities’ environment, and cultural context. These traditional water reservoir structures are not being conserved beneficially in the upcoming decades of its lifespan. Most of the Architectural Marvels are taken for granted, and have evolved and mended itself less in its Urban Context. These structures are in need to serve vitally in the Dry Regions, in order to pertain a better growth and impact of its surrounding Urban Spaces throughout India. At the very end, the paper attempts to make propositions by critiquing the current understanding of cultural heritage and context, stating prepositions on the current usage of the architectural marvels, Stepwells and Temple Tanks of India.

V. Objectives

To understand the relationship of ‘City and Water’ in today’s Urbanized India

To decode the importance of Stepwells & Temple Tanks in the Indian Context

To explore adaptive re-use strategies of Traditional Water Harvesting Systems

6

VI. Research Methodology

Research Method: Historical / Interpretive & Quantitative Analysis

Interpreting the current Urban Context and parallelly developing an understanding of methods to Conserve, plays an important role in historic sites like the prominent Stepwells and Temple Tanks of India. The dissertation study is executed by opening up to the historical context and the listing of various traditional water reservoirs in India, and delving further into comprehensive research.

The methodology for undertaking this study is through Historical (or Interpretive) & Quantitative Analysis of Stepwells and Temple Tanks in the Northern and Southern Regions of India. In context to Stepwells, the regions of Rajasthan, Gujarat, New Delhi, and Maharashtra will be considered. On the other hand, Karnataka, Andhra Pradesh, Kerala and Tamilnadu will be considered, in context to Temple Tanks.

PART 01 - Preliminary Research & Documentation:

• Understanding Stepwells and Temple Tank History – Study of Timelines

• Documentation through literature and live case study of TWHS Systems

• Typology & Components of Stepwells and Temple Tanks

• Comprehending efficiency of these traditional water reservoirs

PART 02 – Interviews & Professional References:

• Chithra Madhavan (Historian) – architectural context & urban relevance

• Ar Ragul Ravichandran (Founder of Vaayil) – adaptive reuse strategies

• Ar. Rajendran (Sthapathi [t] / Temple Architect) – evolution of TWHS

PART 03 – Comparative Study:

• Stepwells – Chand Baori (Rajasthan)

• Temple Tanks – Kapaleeshwarar Theppakulam (Tamilnadu)

PART 04 – Research Analysis:

• Visual Analysis – Architectural Design and Function of Temple Tanks

• Demographic Analysis – Impact and Need for Conservation

• Comparative SWOT Analysis – Stepwells versus Temple Tank

PART 05 – Strategies of Adaptive Re-use

• Inferences from Professionals

• Conclusion

7

VII. Scope & Limitations

SCOPE:

The study brings light to the Architecture & Design of Traditional Water Harvesting Systems in India, particularly covering the design interventions explored in the Urban and Rural Contexts of India Pertaining to focus on the studying interrelation of Stepwells and Temple Tanks, the study focuses on structures built from 500AD onwards. The paper explores documenting, researching and analyzing these traditional structures based on 3 concepts of discussion: Culture + People, Usage + Functionality, Material + Construction. This will include factors like scale, size, locality, functionality, proportions, depths and materiality. The eventual scope of the study leans onto the historical, kinesthetics, and communal aspects of how these systems have impacted the earlier and existing urban context.

Eventually, the study will discuss, how and why these Stepwells and Temple Tanks have a translated usage, that is meaningless in the current Urban Context; exploring how to better re-adapt and re-use these traditional structures, deeming it useful for current and upcoming changes in the environment and society.

LIMITATIONS:

The study limits till the exploration of conservation strategies optimal for major and minor Stepwells and Temple Tanks listed during the preliminary research; dividing the study into three parts. The first part of the study will cover the attributes of these traditional water harvest systems, following up with the second part – where the response of these structures to local Culture, Usage and Construction; will be addressed. The study closes with an in-depth analysis on the various conservation strategies that can be in-cooperated, by the means of case studies.

Due to time constraints, the study will rely on heavy number of secondary resources that act as a backbone to drive the Aim of the research study: to prove the need and necessity of re-adapting Stepwells and Temple Tanks in India. The study will then act as a platform, that can be further explored in the future.

8

VIII. Background

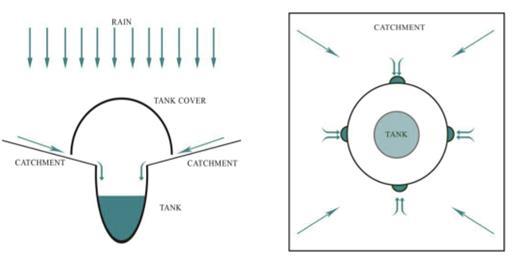

The art and practice of building water harvesting systems was prevalent since the Harappan Times of Ancient India. The Indus Valley Civilization explored methods to receive, conserve and manage water during drought and dry climates. These systems acted as a base for the further development of Stepwells and Temple Tanks exploring intricate engineering and materialconstruction technology, that serves as efficient and sustainable water harvesting structures. Stepwells are built through the excavation of soil to reach a stable ground water table. These structures are excavated to a minimum depth of 5 meters and extend till 20-30 meters deep; the sole reason of building these stepwells is to provide constant water in the dry regions of India. This technology has been explored to defuse Water exploitation and increase management throughout the evolution of Urban Spaces in the Dry Regions of India.

From 2nd to the 4th Century, the development of water harvesting structures became prevalent, spreading knowledge across the Northern Region of India, i.e., Gujarat & Rajasthan, whilst the development of Temple Tanks became a mandatory in the Southern Region of India. Temple Tanks were evolved on the basis of religious necessity. Conducting rituals, taking religious baths, creating a place of worship, and serving as a tank for water used in the Garbhagriha, Temple Tanks played a role in the mechanism of a temple whilst following Shilpa Sastra planning principles, similar to the Stepwells in the North.

In the current scenario, the unchecked extraction and the frequent blocking of inlet ducts has now led towards the drying of Temple Tanks (Kundas), deeming it comparatively less useful in the upcoming years. These tanks have become sinks for sewage and garbage in the local communities – whilst they hold weeds and no biodiversity for maintenance, they make it a challenge for the development of Urban Spaces & the neighborhood.

The revival and construction have the capability to meet the needs of the local communities and habitants, making them a necessary Urban Space to be conserved the right way. The regeneration of Stepwells and Temple Tanks will enhance the Cultural Context and respond to the community by creating a valid Micro-Climate for the Dry Regions of India.

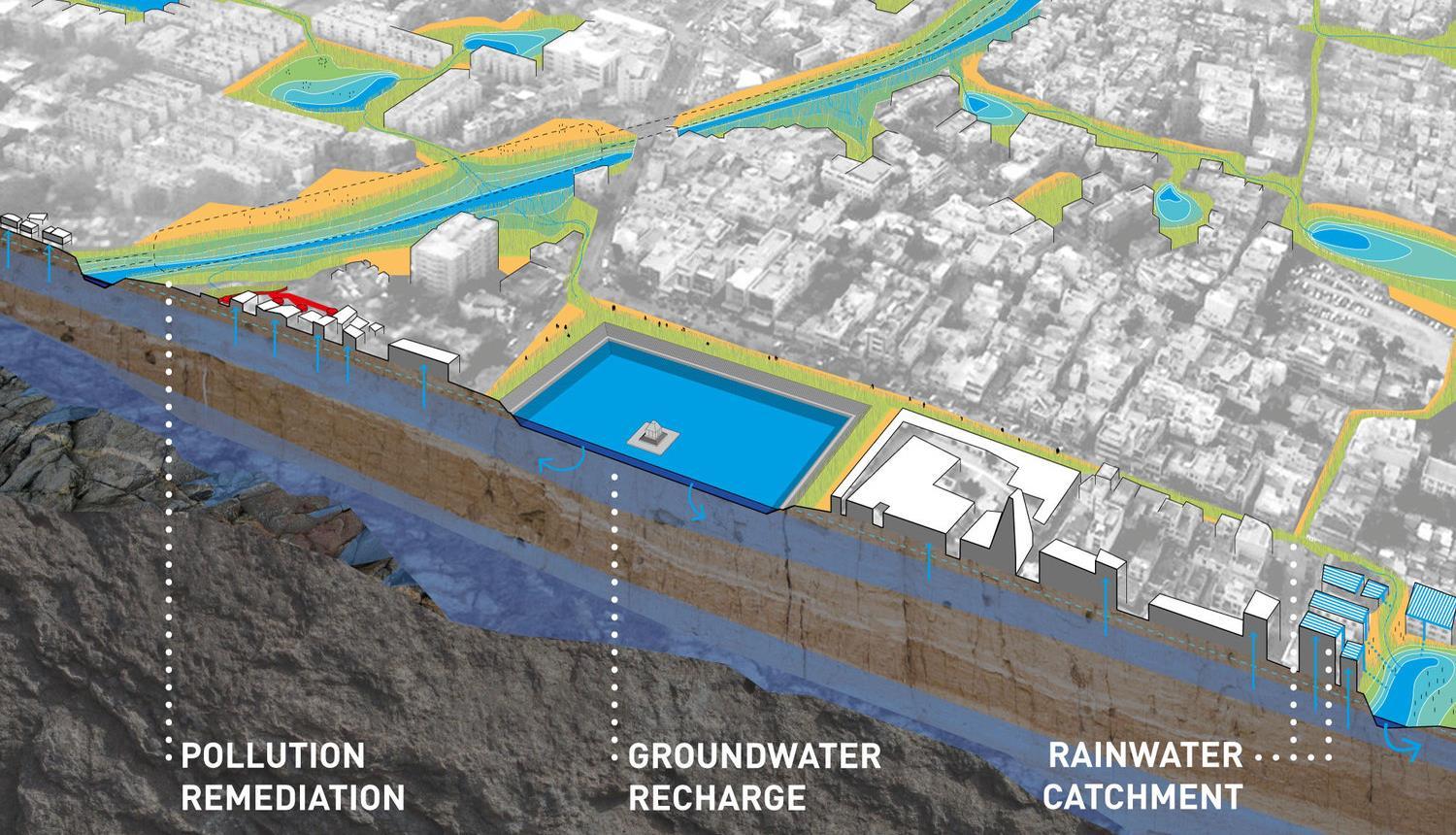

The need of the hour is to revive, restore, reuse/repurpose, and revitalize the Stepwells and Temple Tanks of the Dry regions in India, by integrating them into the Urban Fabric to help them reduce the burden of water shortage. In urban areas, the provision of swales, infiltration, trenches, and bio-retention systems will help to percolate water into the ground, and to direct storm water runoff to catchment points such as these Stepwells and Temple Tanks. At the end, Stepwells and Temple Tanks have a viable way to restore the tactile and experimental relationship in the city with nature, while mitigating the crisis of water in the various regions of India.

9

10

Fig 1: Stepwells of Ahmedabad: Water Harvesting in Semi-Arid Area

1. Introduction to Study

Water has been foreseen to be the cause of the next great global crisis. India has 18% of the world population but only 4% of the world’s water resources. This brings us to the important issue that India may lack overall long-term availability of replenish-able water resources. India is characterized by diverse ecological and cultural regions inhabited by the people. For centuries, a traditional construction for harvesting rain in the arid regions of India, stepwells, has helped people overcome water scarcity in the dry seasons. Stepwells, also known as Baoli [a] and Vav [a], are large subterranean stone structures built to provide water for drinking and agriculture. This study explores these traditional water systems in light of their potential to address the current water crisis in India and as artifacts of cultural heritage. Stepwells of the lost ancient Indian city of Hampi in Karnataka were studied. Furthermore, studies of various stepwells across India were conducted, to develop an understanding of their social and historical importance. The case studies show that the timeless grandeur of stepwells is unmatched but most of them have fallen into neglect and have become dumping grounds for adjacent urban communities.[9]

Thus, the study proposes solutions for the rejuvenation of these man-made groundwater reservoirs for sustainable water consumption The discussions towards the solutions are directed towards Urban & Rural Contexts respectively. For instance, these stepwells can also be turned into major tourist attractions and social interaction hubs in the form of parks, melas[a] and HaatBazaars[a] (Traditional Commercial Centers). This would also effectively generate revenue for maintaining them, one of the major challenges in its upkeep. Thus, the stepwells can be enlivened to improve aesthetics of the urban fabric while serving as solutions to the problem of depleting water resources for a growing population. Furthermore, it would also be instrumental in conserving the cultural heritage of various Indian traditional settlements [12]

1.1. Importance of Water

Throughout history, Water is stipulated as a vital element in the evolution of Human Settlements, that develop roots in tradition, provoking local knowledge, and culture. In context to India and its rich history in the development of the ‘Hindu Way of Living’, Water has been associated towards deities as a divine entity. [1] The element of water itself acts as a means of spiritual, cultural and ecological connection. Thus, waterbodies were treated and used in a systematic, organized mannerism by the practitioners of Hinduism.

For instance, water as a cleaning agent, cleaning the vessels used for the poojas [j], and for Abhishekas [i] or bathing of deities. Several nutrients used for the purpose of bathing the deities and after use of each dravya[a]. Water is used for cleansing the deity. Water offered to the deity and the water collected

11

after bathing the Deities are considered very sacred. This water is offered as Theertha [n] or blessed offering to the devotees. [2]

A cleansing bath was believed to liberate one from sin and impurity:

‘Whatever sin is found in me, whatever wrong I may have done, if I have lied or falsely sworn, Waters remove it far from me…’ – Rig Veda [3]

1.2. Relationship between City & Water

India is a multi-cultural, multi-linguistic and multi-racial nation that carries with it a plethora of representations of its glorious history in art, music, dance, language, and architecture. These expressions in various forms are living museums of the socio-cultural heritage of her people. Several of them are water-related monuments that serve users for their religious, aesthetic, recreational and utilitarian needs

Adjacent to the human settlements, and social-cultural growth of cities in India, water seemed to impacted predominantly towards the ecological or environmental aspects of a place. Amidst the spiritual connection to water, over the years it has become a means of an accommodated source of water, by the means of ornamented pools, river banks, step wells, temple tanks, pumps and freshwater rivers. In particular, the dry regions of India, for instance, Rajasthan, Gujarat, and New Delhi, have been highly dependent on Ground Water, as a resource.

Among these, Stepwells and Temple Tanks have been the most predominant Traditional Water Harvesting Systems (TWHS) that have evolved over decades of experimented technology. Dry Region Cities are abundant in TWHS systems that either have a direct correlation between culture and ‘religion’ or were developed as a means of immediate water resource.

2. Background & Context

2.1. History

Temple tanks are wells or reservoirs built as part of the temple complex near Indian temples. They are called Pushkarni, Kalyani [e], Kunda, Sarovara, Tirtha, Talab, Pukhuri, Ambalakkuḷam, etc. in different languages and regions of India. Some tanks are said to cure various diseases and maladies when bathed in. It is possible that these are cultural remnants of structures such as the Great Bath of Mohenjo-Daro or Dholavira, which was part of the Indus Valley civilization. Since ancient times, the design of water storage has been important in India's temple architecture, especially in western India where dry and monsoon seasons alternate. [6] Temple tank design became an art form in itself. An example of the art of tank design is the large, geometrically spectacular Stepped Tank at the Royal Center at the ruins of Vijayanagara,

12

the capital of the Vijayanagara Empire, surrounding the modern town of Hampi. It is lined with green diorite and has no drain. It was filled by aqueduct. The tanks are used for ritual cleansing and during rites of consecration. The water in the tank is deemed to be sacred water from the Ganges River.

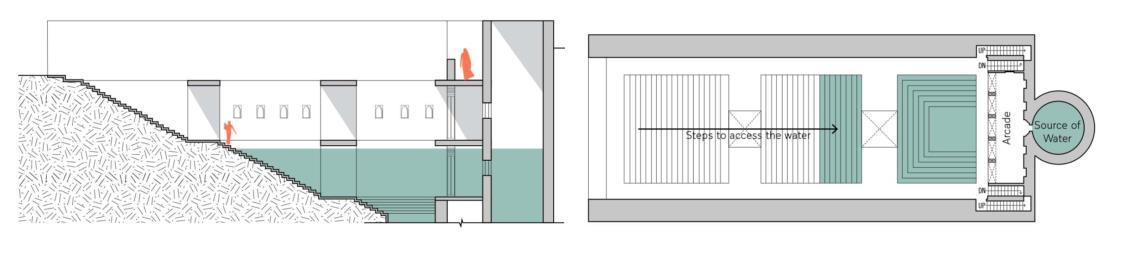

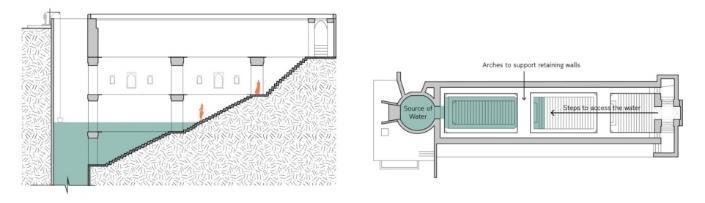

In India, a stepwell is a deep masonry well with steps going down to the water level in the well. It is called a vav in west India and a Baoli in north India. Some were built by kings and were richly ornamented. They often were built by nobility, some being for secular use from which anyone could obtain water. Stepwells usually consist of two parts: a vertical shaft from which water is drawn and the surrounding inclined subterranean passageways, chambers and steps which provide access to the well. The galleries and chambers surrounding these wells were often carved profusely with elaborate detail and became cool, quiet retreats during the hot summers. The most common terminologies used to define these TWHS are as follows:

• Kalyani [e] – temple tanks for ritualistic baths before entering temples

• Kulam [f] – temple tank directly derived from the abundant groundwater

• Vav – a stepwell that can be accessed from 3 sides of the well

• Baori [b] – long corridors that lead towards a wide vertical shaft well

2.2. Evolution

This research is based within historicism and its inherent practices to conserve obsolete and symbolic structures. Due to their sacred nature these types of structures are often preserved, remain untouched and left to decay, or are forgotten altogether. Historically the Western Indian stepwell archetype provided public access to water and therefore, it served as an important public gathering space that was predominantly used by women. This thesis proposes that obsolete sacred spaces like the stepwell that no longer serve their intended utilitarian function can be trans-programmed and re-contextualized as public infrastructure serving the contemporary needs of the community. Studying specifically the Adalaj Stepwell, it explores how renewed public space can be created by deeply rooting thoughtful architectural interventions in the collective memory of the building.[8] These interventions balance preservation with revitalization by providing the services and spaces needed to give the historic monument new life as a contemporary public library. The construction and use of cisterns to store rainwater can be traced back to the Neolithic Age, when waterproof lime plaster cisterns were built in the floors of houses in village locations of the Levant, a large area in Southwest Asia, south of the Taurus Mountains, bound by the Mediterranean Sea in the west, the Arabian Desert in the south, and Mesopotamia in the east. By the late 4000 BC, cisterns were essential elements of emerging water management techniques used in dry-land farming.

13

Initially constructed as crude trenches, they slowly evolved into engineering marvels between 11th-15th Century. Bansi Devi, who rears cattle for a living in Rajasthan, has already noticed a change. "We had to walk for hours searching for water," she says. "Now I can use water from the revived Baoli in my village for our domestic use and also for feeding and washing the cattle." Gram Bharati Samiti (Society for Rural Development), a non-profit in the Jaipur district of Rajasthan, has carried out restoration work of seven stepwells in the villages of Rajasthan, providing around 25,000 people with a more reliable water source.

"We have restored seven stepwells where ground water has been recharged and storage capacity has increased," says Kusum Jain, secretary of Gram Bharati Samiti, Society for Rural Development in India. "Most stepwells can provide ample water for the daily needs of the villagers. It saw a unique coming-in of volunteers from different communities, exemplifying India's religious harmony." [9]

14

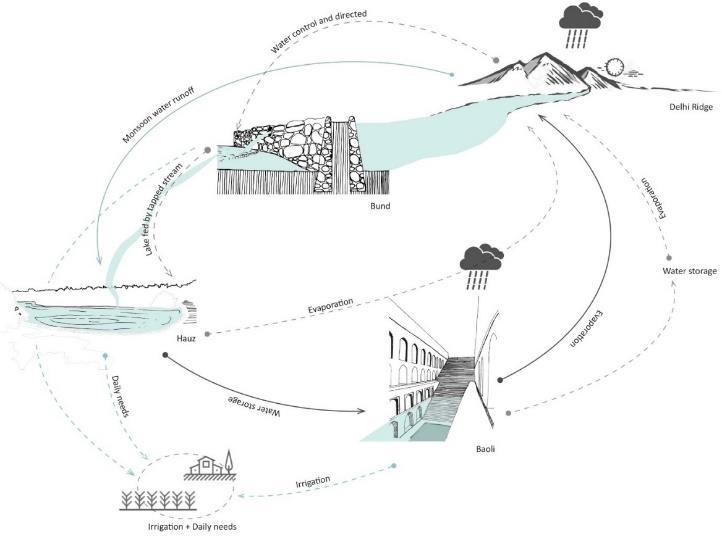

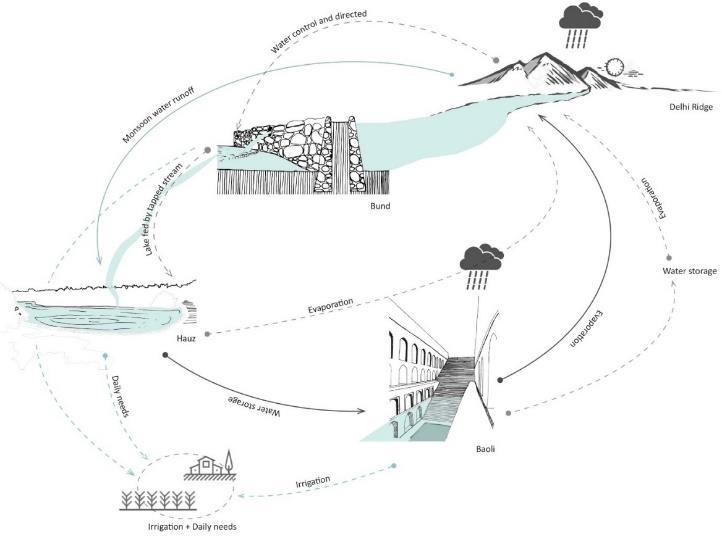

Fig 2: Evolution Mapping of Traditional Rainwater Harvesting Systems – where locals convert river streams and Ground water into Architectural Marvels in the early 11th to 12th Century

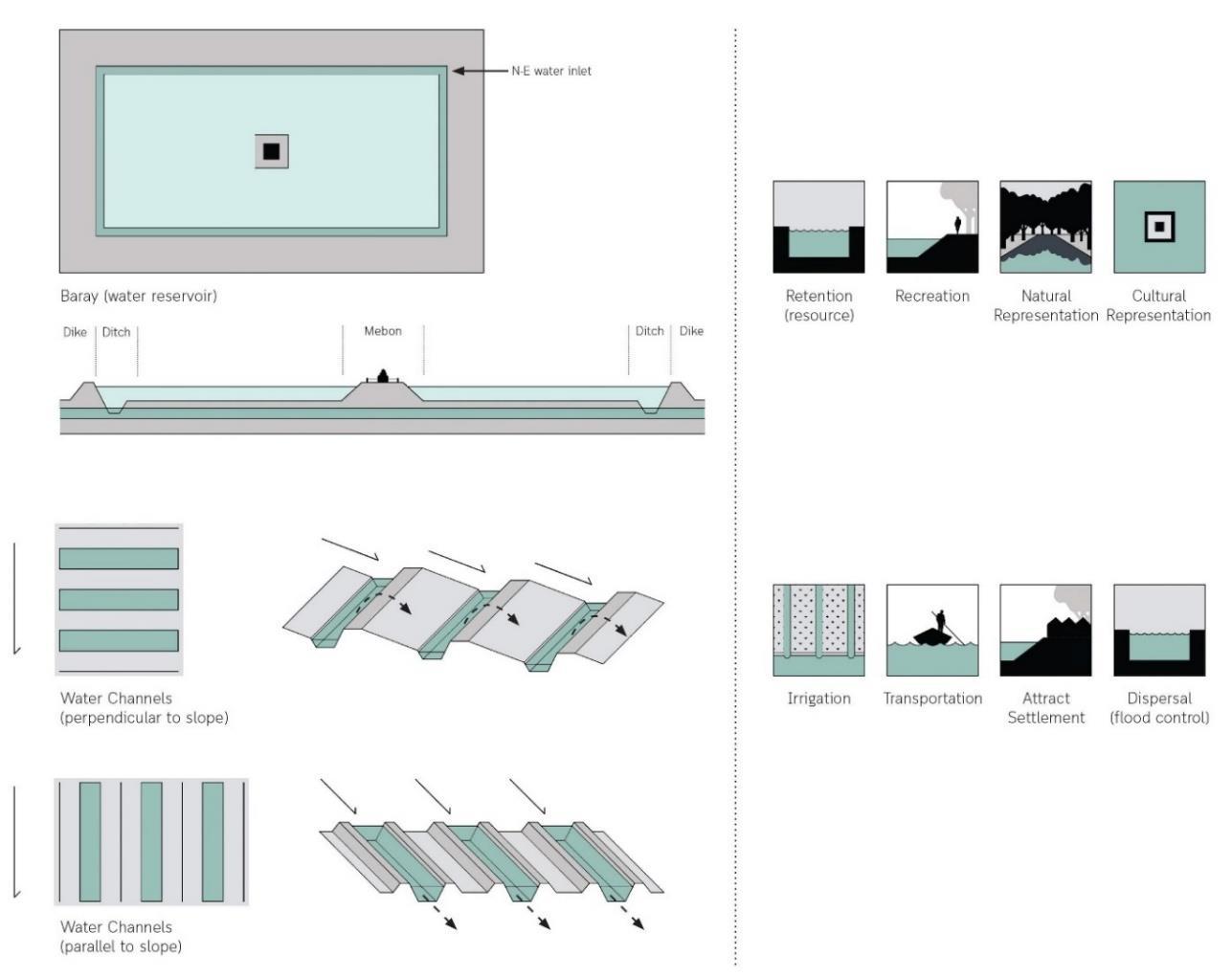

2.3. Typology

In the Indian Context, stepwells have various typologies in relation to their geographical locality, cultural context, and vary through its Urban and Rural Integrity. On the other hand, Temple Tanks have very distinctive purposes; serving them as a similar planning water harvesting system.

This relationship between the shape of the land and the settlement often affects the organization and the character of the built form. Generally, a temple marking the center of the settlement occupies the highest point of the mound and the streets follow the pattern of water flow as it drains away from this high ground into the surrounding agricultural areas that support the settlement. These manmade lines connect with the natural flow to mark the movement of man and water through the landscape.

15

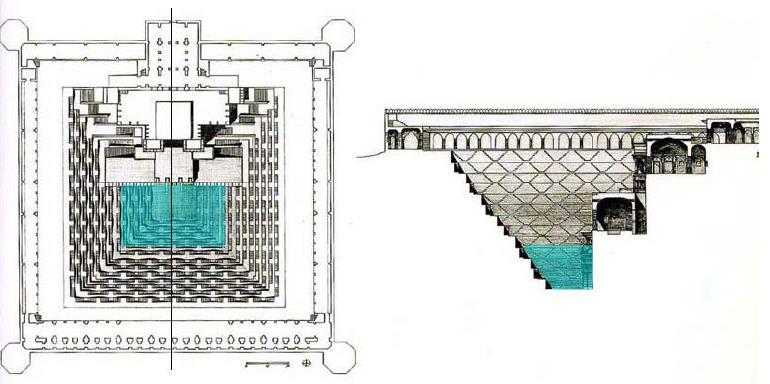

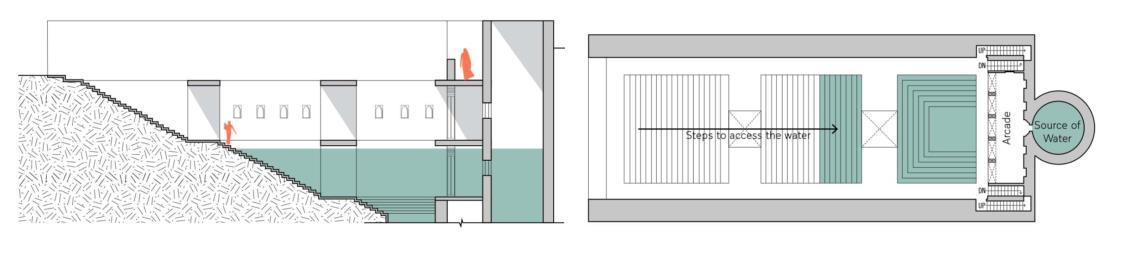

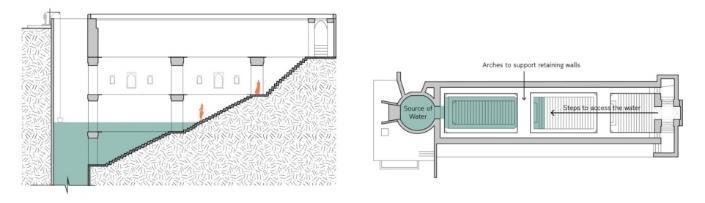

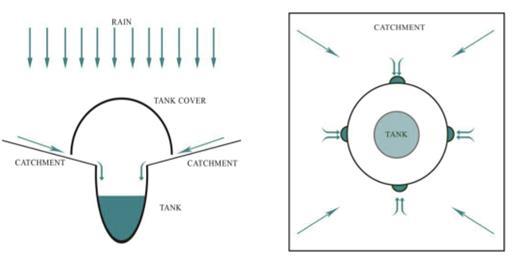

Fig 3: Outline of Temple Tank + Open Stepwell + Closed Stepwell

Fig 4: (Clockwise) Typology 2, Cheela Bawadi; Typology 1, Atreya Bawadi; Typology 3, Sarai Bawadi; Typology 4, Bengali Baba ki Bawadi; Typology 5, Parshuram Dwar ki Bawadi.

Stepwell Typologies

Typology 1: Rectangular Plan with Open Square Shaft

Typology 2: Rectangular Plan with Semi-Open Circular Shaft

Typology 3: Rectangular Plan with Open Circular Shaft

16

Fig 5: Typologies of Stepwells adapted from Anubhuti Chandna, 2019

Temple Tank Typologies

17

Fig 6: Typologies of Stepwells adapted from Krit Thienvutichai, 2020

3. Traditional Water Harvesting Systems (TWHS)

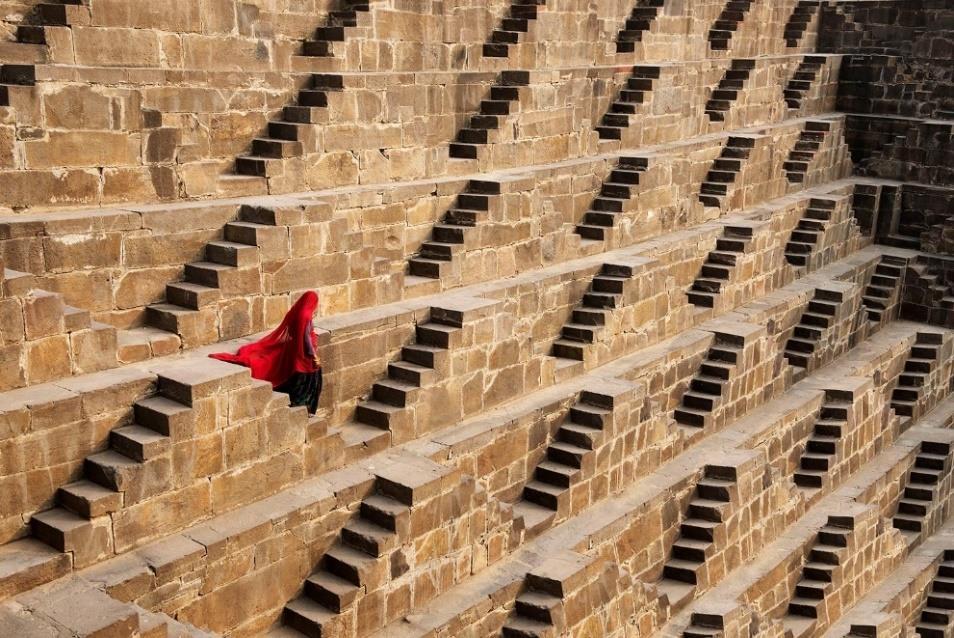

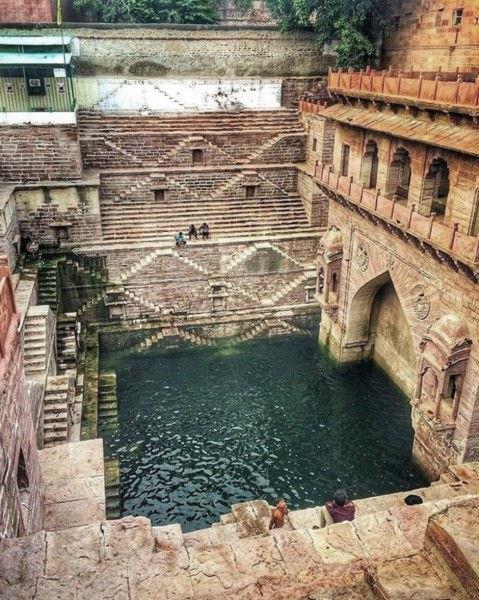

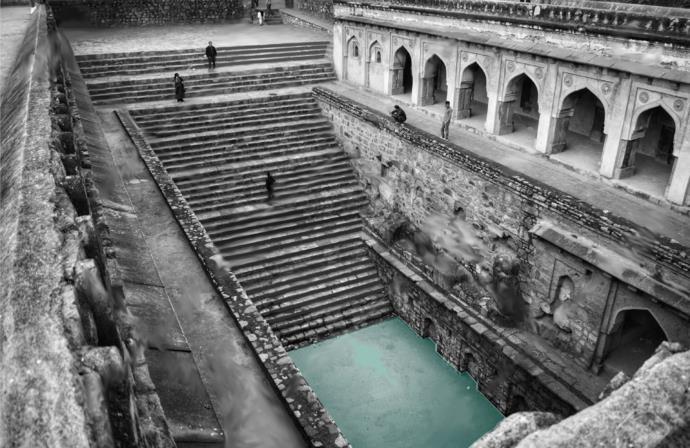

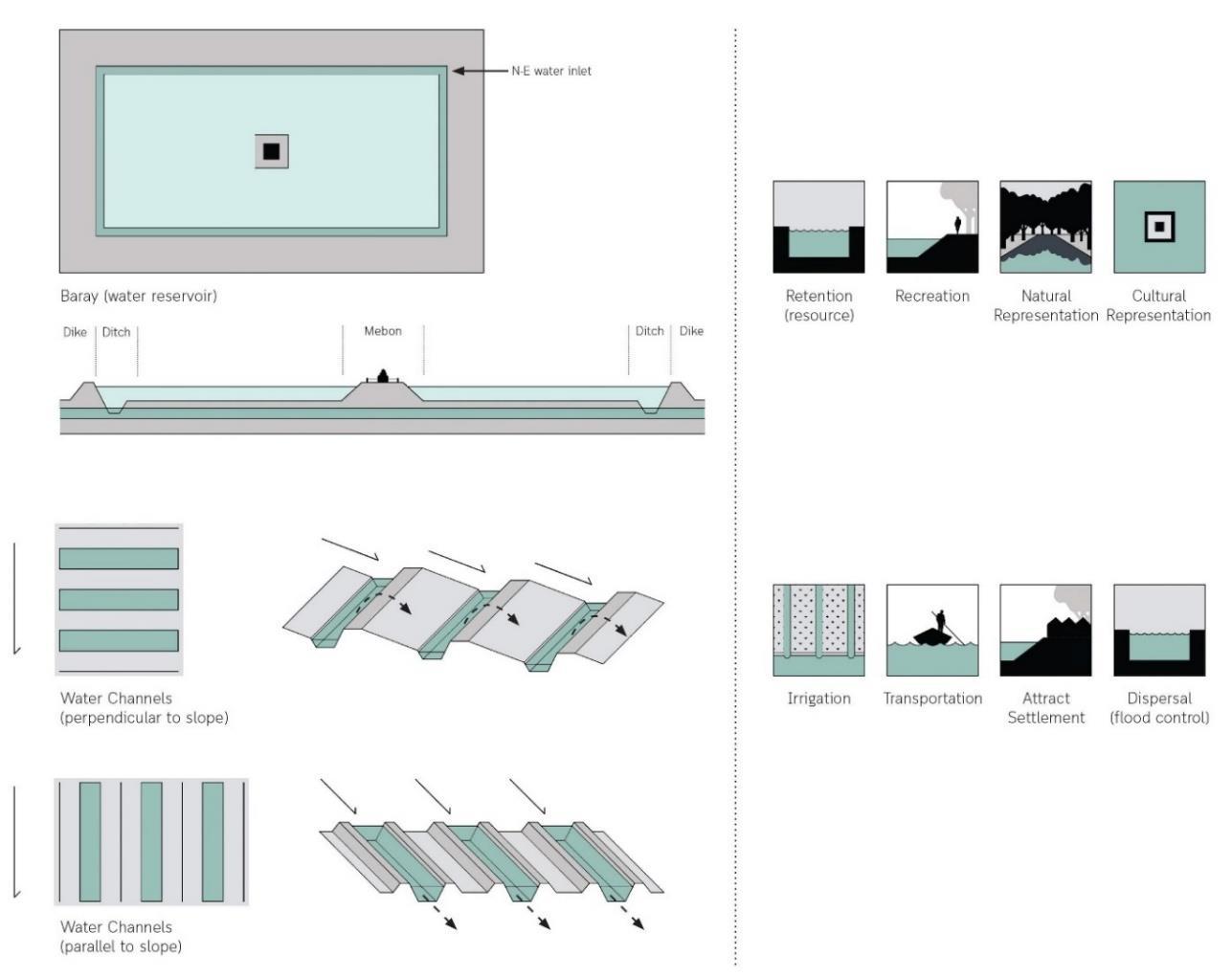

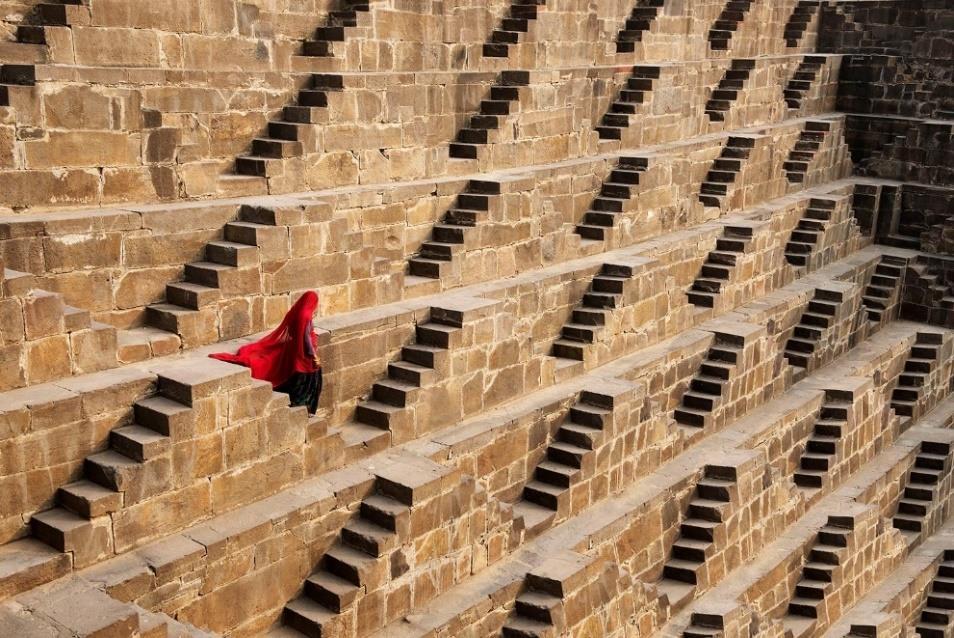

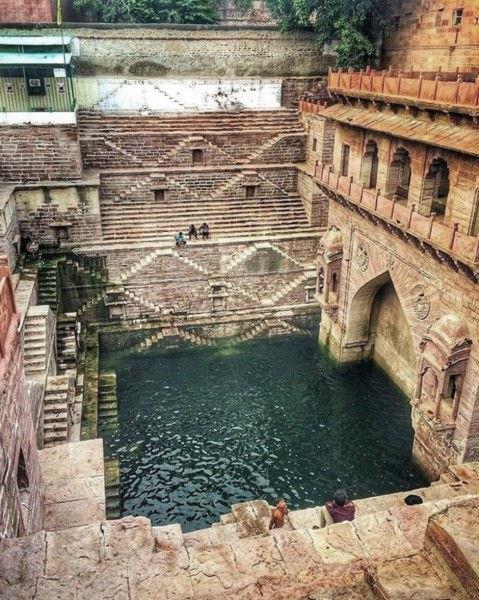

3.1. Stepwell: Chand Baori in Rajasthan

Chand Baori [b] in Abhaneri village (a corruption of Abha Nagari meaning “City of Brightness”) is the world’s largest and deepest step well, constructed over a thousand years ago in the 9th Century by Raja Chand to resolve water shortages via water harvesting in the arid Rajasthani area. Step wells (Baori), is unique and remarkable both in their engineering and architecture a unique water management system. It is a feat of mathematical perfection from an ancient time as Chand Baori extends approximately 100 feet into the ground, down 3,500 steps and 13 levels presenting the most amazing symmetry as they taper down to meet the water pool. Locals claim that the pool was designed and engraved as an upside-down pyramid.

This square-shaped architectural marvel built with porous volcanic stones lets water seep in from the bottom and the sidesof the well. The Baori has a precise geometrical pattern, with 3,500 narrow steps arranged in perfect symmetry, which descend 20m to the bottom of the well. The Baori narrows as one gets closer to the bottom.[10]

Despite its open architecture that exposes it to the intense heat, as this well has steps built into the sides that can be descended to reach the water at the bottom which is about 64 feet deep with 13 floors. The well has its own climate at the bottom where it is about 5-6 degrees cooler than up above. The steps make a mesmerizing play of triangles on three of the descending walls while the fourth side boasts of a pavilion. The side that has the pavilions has niches with beautiful sculptures including religious carvings, beautiful carved jharokhas and galleries supported on pillars. There is a royal residence with rooms for the King and the Queen and a stage for the performing arts. [10]

18

Fig 7: Photograph of Chand Baori in 2016

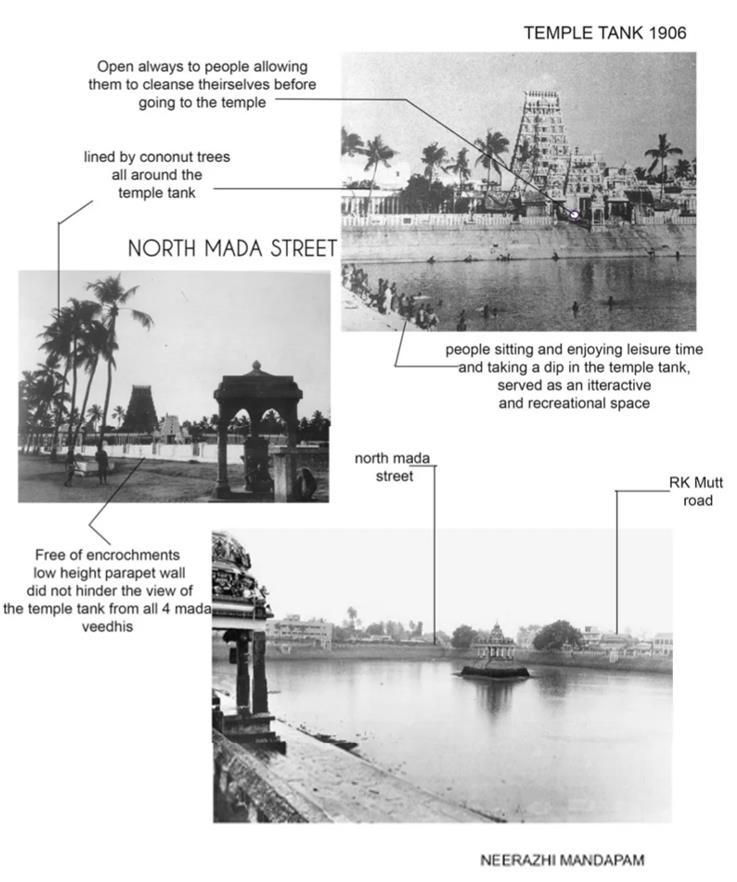

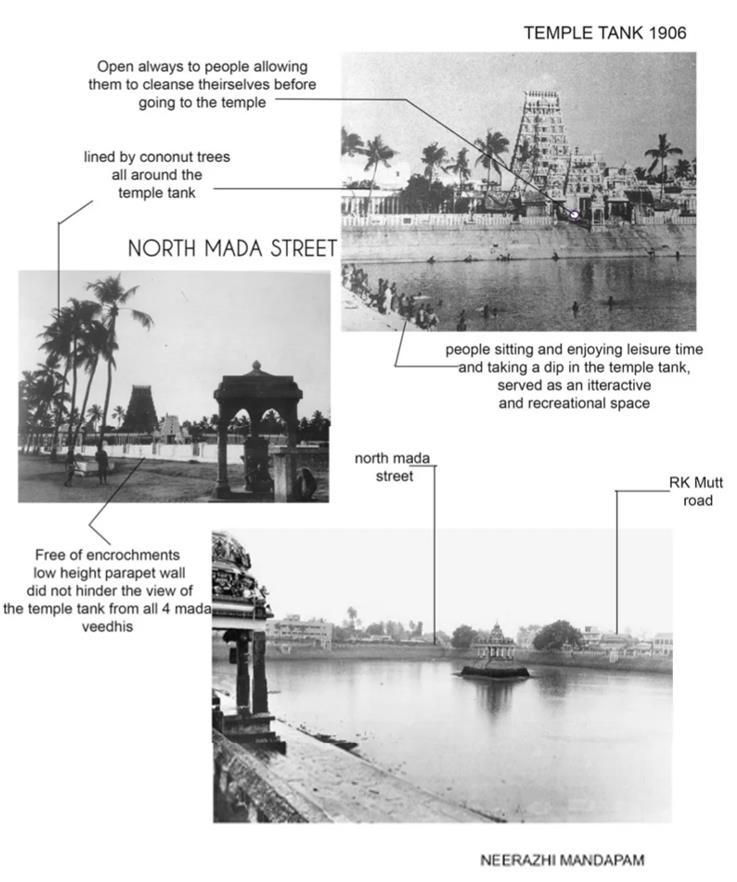

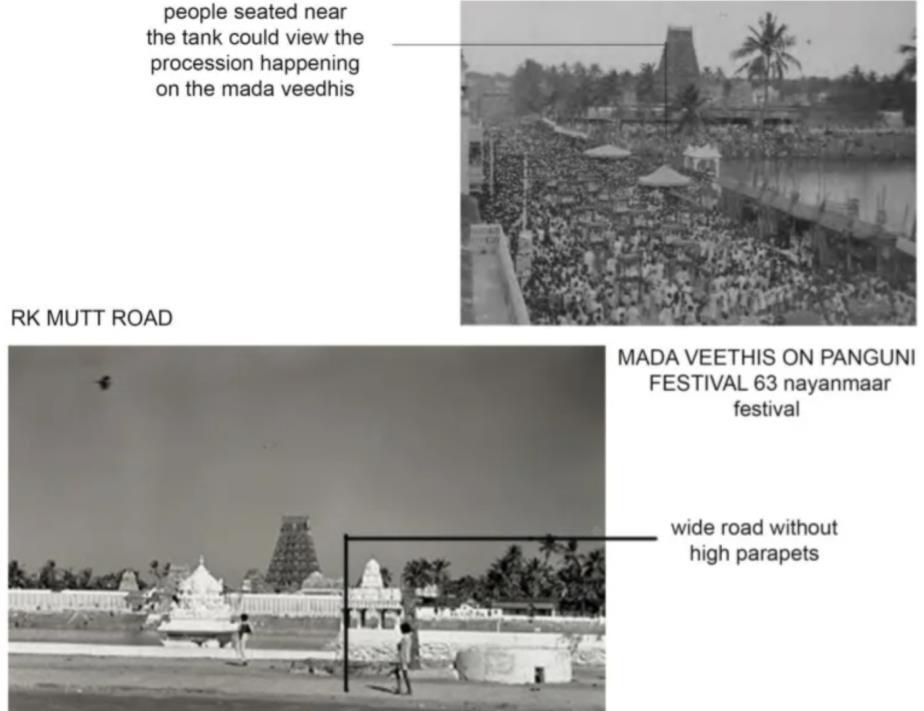

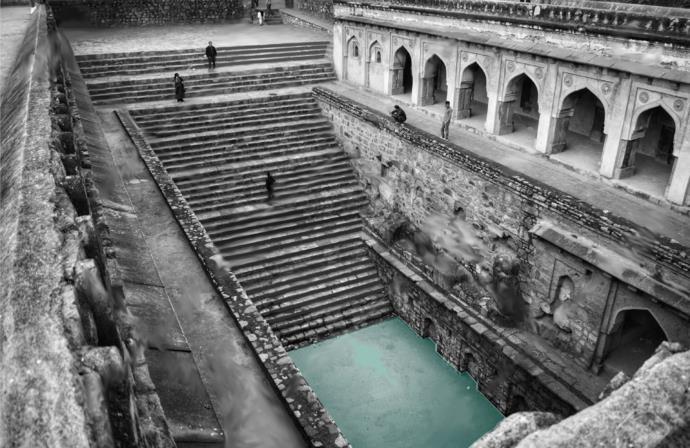

3.2. Temple Tank: Kapaleeshwarar Theppakulam in Tamil Nadu

The Kapaleeshwarar temple is of typical Dravidian architectural style, with the gopuram overpowering the street on which the temple sits. This temple is also a testimonial for the Vishwakarma Sthapathi [t]. There are two entrances to the temple marked by the gopuram on either side. The east gopuram is about 40 m high, while the smaller western gopuram faces the sacred tank.

The Theppakulam, or the temple tank, lies to the west of the temple. Also known as the Kapaleeshwarar Tank or the Mylapore Tank, it is one of the oldest and well-maintained Theppakulam in the city, measuring about 190 m in length and 143 m in breadth. The tank has a storage capacity of 119,000 cubic meter and has water all through the year.

The 16-pillared, granite-roofed structure, known as the mandapam at the center of this tank is known for its significance during the three-day annual float festival, when idols of Lord Kapaleeshwarar and other deities are taken around the tank to the chanting of Vedic hymns. In 2014, ₹ 56.5 million was allotted to build a 2,150-meter-long pavement around the tank. [6]

About Kapaleeshwarar Temple: (adjacent to the Temple Tank)

Kapaleeshwarar Temple is a Hindu temple dedicated to lord Shiva located in Mylapore, Chennai in the Indian state of Tamil Nadu. The form of Shiva's consort Parvati worshipped at this temple is called Karpagambal is from Tamil ("Goddess of the Wish-Yielding Tree"). The temple was built around the 7th century CE and is an example of Dravidian architecture.

The temple has numerous shrines, with those of Kapaleeshwarar and Karpagambal being the most prominent. The temple complex houses many halls. The Arubathimoovar festival celebrated during the Tamil month of Panguni [o] as part of the

is the most prominent festival in the temple.

19

ப்ரஹ்மமோத்சவம்

Fig 8: Photograph of Kapaleeshwarar Temple & Tank from 2009

4. Comparative Study – an Architectural Analysis

4.1. CULTURE + PEOPLE

To analyze the Culture & People of Stepwells and Temple Tanks, the historical context and its evolution of Chand Baori and Kapaleeshwarar Theppakulam is vital.

Stepwell (Literature Case Study) – Chand Baori

Built sometime in the 8th or 9th-century AD, it is the oldest surviving stepwell in the region. It was built by the King of Chanda and includes a temple, pillared corridors, and other highly ornate masonry structures. Chand Baori was used as a community gathering place for locals during periods of intense heat. One side of the well has a haveli pavilion and resting room for the royals. Pilgrims are said to have found comfort in quenching their thirst and finding a resting spot at the steps of Chand Baori after their long travels.

Cultural Sounds and Celebrations:

Abhaneri festival is celebrated in the period between Kajli Teej and the Marwar festival of Jodhpur, usually in September and October. It can last for 2-4 days. This festival is perfect for planning a short getaway, especially from Delhi and neighboring areas, to experience Rajasthan's color, vibrancy and richness. Attractions like the Kalbelia Dance[u] , the puppet shows and Langa singing.

5:00pm

10am to 4pm Source

9 AD History: Royal Personnel’s Recreational Zone

Table 1: Listing of Activities in Chand Baori

20

Timing Culture and Activities of People Varies Gathering of Pilgrims

/ Ceremonial Activities

Religious

of

&

Shade

Water: Haveli Pavilion

Fig 9: Kalbelia Dance & Langa Singing at the Abhaneri Festival

Temple Tank (Live Case Study) – Kapaleeshwarar Theppakulam

The temple priests perform the pooja [j] (rituals) during festivals and on a daily basis. Like other Shiva temples of Tamil Nadu, the priests belong to the Shaivite community. Each ritual comprises four steps: abhisheka [i] (sacred bath), alangaram[p] (decoration), neivethanam[q] (food offering) and deepa aradanai (waving of lamps) for both Kapaleeshwarar and Karpagambal.

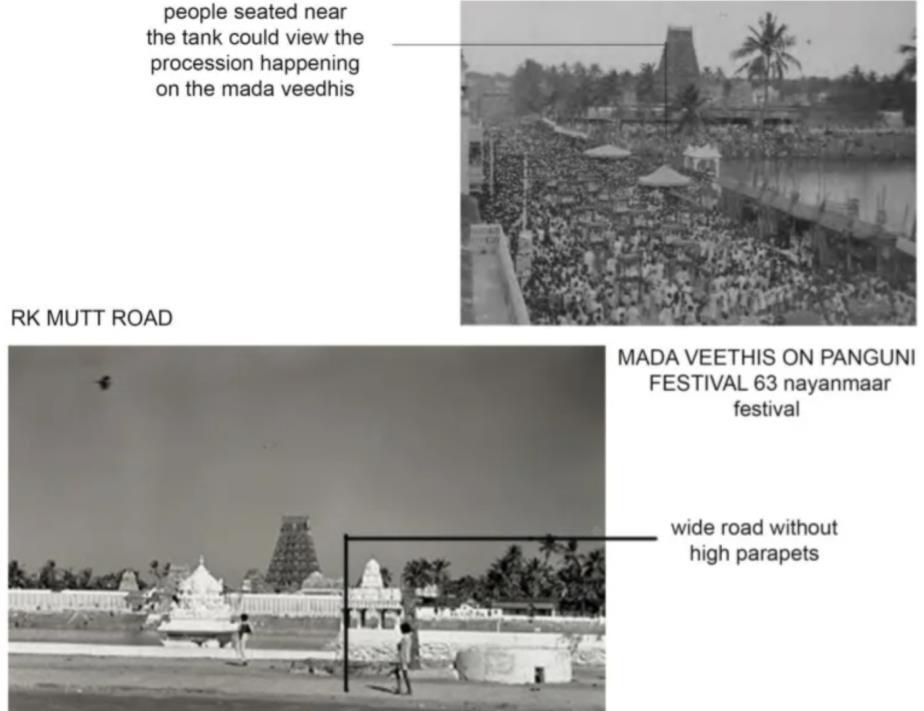

Cultural Sounds & Celebrations:

Mylai [a.1] Kapaleeshwarar Temple / Mylapore Kapaleeshwarar Temple

Panguni [o] Peruvizha chariot festival, dedicated to Lord Shiva located in Mylapore, Chennai. The most important festival observed in this temple is the Panguni [o] Peruvizha celebrated for nine days. During the festival, the idols of Kapaleeshwarar and Karpagambal are beautifully decorated with clothes and jewels, are mounted on a chariot (therotsavam [y]), and then taken around the temple. The Arubathimoovar festival is one of the most important processions at the Mylapore Kapaleeshwarar Temple, during this festival with sixty-three Nayanmars who have attained salvation by their devotion to Lord Shiva.

Timing Culture and Activities of People

11am & 5pm

1pm + 5pm + 7pm

Return by 9:00pm

6:00am to 7:30am

Abhishekam [i] (Sacred Ablution) –performed twice a day

Temple Premises: Ushathkalam + Kalasanthi + Uchikalam

Thai Poosam [z] – Annual Float Festival –Tank is used to float deities on an elegant boat

Opened in the morning for public

Inference: Inviting various activities near the Stepwells or Temple Tanks allow the place to attract itself as an active icon for gathering. It will become a pointof-meet, creating memories and traditions for communities in Urban spaces.

21

Table 2: Listing of Activities in Kapaleeshwarar Theppakulam

Fig 10: Waving of lamps & Musical Concerts in the Temple

22

Fig 11: Analysis of People & Surroundings over a decade ago

4.2. USAGE + FUNTIONALITY

To analyze the Usage and Functionality of Stepwells and Temple Tanks, considering 3 vital points of debate would suffice in understanding the main differences: Development, Catchment Area & the Water System Plan.

Stepwell (Literature Case Study) – Chand Baori

The stepwells of North, West, and East India contain water from the underground water table. This water is considered sacred, pure and healthy enough to rid of ailments by local villagers as in, Rajasthan and Gujarat. These stepwells were used to satisfy the thirst of traveling nomads and villagers. Some stepwells (such as Gandhak-ki-Baoli) are known to possess special healing qualities in their water. Due to the soft fertile soil in the plains, the stepwells could go several meters deep to access groundwater reserves of water.

23

Fig 12: Rajasthan Water System Plan

Chand Baori – Usage & Functionality

Nomenclature Baori, Baoli, Bavdi

Case Study Chand Baori (Abhaneri), Rajasthan

Microclimate 5 – 6 degrees cooler nearing shaft

% Per annum Dry Area – Stagnant / Damaged

Development

Catchment Area

Built in 8th / 9th Century AD – overnight

Ground Water Table is aggravated from Cauvery

Vertical Shaft tends to fill up during rains

Experiencing blockage underground – due to Algae

High declination of biodiversity nearby

Water System Plan Needs re-routing / varied means of getting GW

3: Analysis of Usage & Functionality of Chand Baori

Chand Baori is a deep four-sided well with a large temple located in the back of the well. The basic architectural aspects of the monumental well consist of a long corridor of steps leading to five or six stories below ground level which can be seen at the site. The state of Rajasthan is extremely arid, and the design and final structure of Chand Baori was intended to conserve as much water as possible. Ancient Indian scriptures made references to construction of wells, canals, tanks and dams and their efficient operation and maintenance. This site combined many of these operations to allow for easy access to local water. At the bottom of the well, the air remains 5-6°C cooler than at the surface, and Chand Baori was used as a community gathering place for locals during periods of intense heat. One side of the well has a haveli pavilion and resting room for the royals.

24

Fig 13: Catchment Area of Water – driven from river Cauvery

Table

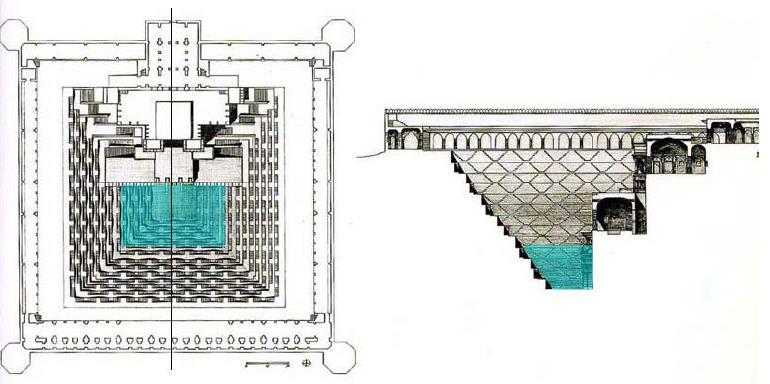

Temple Tank (Live Case Study) – Kapaleeshwarar Theppakulam

The six-acre Mylapore Tank, the city’s largest rainwater harvesting structure, now has five bore wells on its bed, pumping out water to keep it alive – the state calls it conservation; experts dub it ill-afforded luxury in the time of drought. The Water is thus maintained at a level of 2 ft; where it used to be at a level of 5 ft during the Summer Season. “Tanks are both a source and a sink. It helps recharge groundwater by aiding percolation.” Quoted by Sekhar Raghavan, director of Rain Center, adding, “Now is the time they should be desilting tanks for the coming monsoon, not mining water.”

25

Fig 14: Water System Plan for Kapaleeshwarar Theppakulam in Mylapore –Connecting this to an Urban Scale as the Temple Tank is connected to various other small Chithrakolam

Kapaleeshwarar

– Usage & Functionality

Nomenclature Kalyani [e], Kulam, Pushkarni, Kund

Case Study Kapaleeshwarar Theppakulam [g]

Microclimate 1 – 2 degrees cooler near zone

% Per annum 5% Raise per Annum

Development

Built in 6th / 7th Century AD during the Pallavas

Catchment Area

Located near Seashore – advantageous due to Slope Filters oneself from various Chithrakolam nearby Aiding with bore wells – Ground water rejuvenated Increases Ground Water Table – biodiversity alive

Water System Plan

Inference: Needs desilting immediately to preserve structure, preventing it from deteriorating and losing its Cultural and Functional Values as a built structure

Kapaleeshwarar Theppakulam Temple Tank as an ancient technology were not used to collect water for reuse, but to recharge the aquifer, to later be extracted through personal wells. These tanks served as a barometer of the city’s underground resource, making its fluctuating level visible. Today this system has been forgotten as the city grows with modern infrastructure, leading to interrelated disasters of floods, droughts and pollution. By the means of diverse tactics and green-blue strategies, the temple tanks will be restored to its original purpose as essential points of water recharge in the city.

26

Fig 15: Catchment Area of Water – driven from Ground Water Recharge & Surface Runoff

Theppakulam

Table 4: Analysis of Usage & Functionality of Theppakulam

4.3. MATERIAL + CONSTRUCTION

Stepwell – Chand Baori, (Abhaneri) Rajasthan

Stepwells were built by excavating several stories underground in order to reach the water level of a particular site. Once complete, the wells, and walls, of the excavation were lined with masonry (usually without mortar), and staircases of a varying design were also added from the ground level to the water reservoir. The stepwell was built in a typical mannerism, where a vertical shaft is framed from which water is drawn, and a surrounding inclined subterranean masonry structure (sometimes with passageways, chambers, and temples). Some also include galleries and other chambers surrounding the wells, often ornately carved, to provide cool, quiet retreats for visitors. Built sometime in the 8th or 9th-century AD, it is the oldest surviving stepwell in the region. It was built by the King of Chanda and includes a temple, pillared corridors, and other highly ornate masonry structures.

Temple Tank – Kapaleeshwarar Theppakulam, (Mylapore) Tamilnadu

The tank was built in a typical mannerism, where a vertical shaft is framed from which water is drawn, and a surrounding inclined subterranean masonry structure (sometimes with passageways, chambers, and temples). Some also include galleries and other chambers surrounding the wells, often ornately carved, to provide cool, quiet retreats for visitors.

Northern India

Southern India

Nomenclature Baori, Baoli, Bavdi Kalyani [e], Kulam [f], Kund

Case Study

Chand Baori

Kapaleeshwarar

Theppakulam [g]

Dynasty/Area Period of Iltutmish Pallavas, Chalukyas, Hoysala

Architectural Style

Mihir Bhoj Architecture Dravidian Architecture Mensuration

Technique Positive & Negative Construction

x 143m

Excavation Positive Construction

Material Brick and Stucco Brick Schist Stone Blocks

Construction Lime Bond + Lime Finish Mandapa Walls @ 7ft Height

Gandhak (Sulphur)

Special Techniques & Characteristics

Fills up during Monsoon

Havelis installed - Vaav [c]

Connects river table

Acoustics of Baoli

Usually contains Water all year

Adjacent to deity Shiva

Temple

Connected to Chithrakolam [h]

27

19.5m deep (13 Stories) 5ft deep 35m

35m 190m

x

Table 5: Material & Construction Comparison between the Case Studies

4.4. Preservation of Architectural History

Plunging into the earth, stepwells like Chand Baori were built in droughtprone regions of India to provide water all year round, ensuring communities had access to vital water storage and irrigation systems. Centuries of natural decay and neglect, however, have pushed these structures into oblivion. Once, the people were living in the forested areas and making judicious use of available natural resources, However, modernization, industrialization and urbanization are seeing a shift from the traditional belief system, which is also resulting in discontinuation of practices that were in harmony with the environment.

Importance of preserving Water Harvesting Systems in India:

India receives about 400-million-hectare meters of rain annually, but nearly 70% of surface water is unfit for human consumption due to pollution. India is ranked 120th out of 122 countries in the water quality index. An estimated 200,000 people die every year due to inadequate water. [9]

The Indian Urban Development governing bodies emphasize the need to use India's historic water management systems for solutions to these problems. States can leverage new technologies to modify traditional water systems for local requirements. In a nation where 600 million people – around half the population – face severe water shortages daily, traditional water-harvesting solutions are a harbinger of hope. "With India's water table rapidly declining, stepwells can help refill ground aquifers and harvest runoffs. In three months during the rainy season, millions of liters of water can be collected," says Ratish Nanda, a Conservation Architect and projects' director at the Aga Khan Trust for Culture, an organization leading restoration effort. [13]

28

Fig 16: Showcasing the Stepwell (Left) Chand Baori & Temple Tank

Fig 17: (Right) Kapaleeshwarar Theppakulam – preservation of Architectural History through Adaptive Re-Use

At the end, these structures are now abundant in number throughout India, the essence of the challenge lies on how Architects and Historians can preserve these marvels as an identity of Traditional Water Harvesting Systems, parallelly judging its flexibility for adaptive re-use. By conducting a SWOT Analysis as the Inference of the Case Studies analyzed, with respect to Stepwells and Temple Tanks, in the previous chapters, the exercise on determining the flexibility of transformation becomes easier.

SWOT Analysis for Chand Baori:

Chand Baori construction and usage has been prevalent for a long duration of time – with royal patrons recognizing the importance of the concept and giving it a push. The most highly embellished step- wells are the ones where the patron took a greater interest. Step-wells went beyond being just sources of water. They were public places and congregation points, especially for women whose role was to bring water to the house.

Two Facts - that numerous patrons of step-wells were women and that iconography depicting goddesses often in the structures – are clear pointers that the spaces are mostly and predominantly used by women in the previous eras: where a stepwell is seen as a larger complex, contains a Haveli with a Temple, Harshta Mata [b.1] Temple, dedicating to a goddess who represented joy and happiness. [11]

Chand Baori – SWOT Analysis for Adaptive Re-Use

Strengths Weaknesses Opportunities Threats

Geometry of the Stepwell gains attention from visitors

5-6 degrees of temperaturecooler at the bottom

Haveli acts as a shading – 2 linear balconies

Water scarcity

High Algae

Development

Construction of the Stepwell is too steep Clogging of the tank has led to worsened quality of services –leading to drying

Surface area for creating Mela [a] areas

Rooms in the Haveli can be renovated for use

Easy to build (+ve) construction on the Stepwell for future development or adaptive re-use

Water Clogging led to lifestyle endanger

Structure of Haveli is fragile / broken

Pumps and Pipe construction has led to drying of stepwell

29

Table 6: Chand Baori – feasibility in Adaptive Reuse Transition

SWOT Analysis for Kapaleeshwarar Theppakulam:

"Tanks are both a source and a sink. It helps recharge groundwater by aiding percolation,” said Sekhar Raghavan, Director of Rain Center, adding, “Now is the time they should be desilting tanks for the coming monsoon, not mining water at all.” The HR & CE Official, however, said the water used was minimal. The pump sets have a capacity of only one horsepower each and the wells are not more than 25 ft deep.

At this juncture, the public cannot afford to lose water, which in this case would be due to evaporation, and has the public proved in the year of 2019. On this note, a survey conducted by the Rain Center shows the Water Table in Mylapore which stood a depth of 6.2m has dropped to 7.2m within a 2-month duration. In relation to this, they have noted that in a one-kilometer radius, the Kapaleeshwarar temple tank is deemed to showcase being dry, without the aid of any action from Architects and Urban Designers.

From the live case analysis conducted at the Site of Mylapore in Kapaleeshwarar Temple Premises, the Residents and Local Workers claim that the water being extracted from the ground is of a high rate, over the period of time. Environmentally, this is a very poor solution to accumulate water for daily basis. This has been a common practice in front of the naked eye, despite a covering of borewell inside the tank by the HR&CE Department. Technically, water is being pumped, only for the sole reason of keeping the tank’s biodiversity alive, and not for any other purpose – wasting the system and capacity, damaging its future potential in the long run. [11]

Kapaleeshwarar Theppakulam – SWOT Analysis for Adaptive Re-Use

Strengths

Mechanism of rainwater harvesting is intact till present Tank was recently desilted conservation of water is at highest Surface Runoff allows recess water to get recharged

Weaknesses

The frequent uncertainty of the water quality diminishes ecosystem Water and Sewage Stagnation: plaguing residents nearby –pollution

Opportunities Threats

The vast space allows space for Plaza design

Storm Water Drain

Work can be repaired by opening bore wells nearby

Open Areas: planting trees & landscape

Sea levels rising is affected salt content – 4400 spm

Urbanization & Pollution, diminish architectural quality

Vanishes Clay Bed not facilitating seepage

30

Table 7: Kapaleeshwarar Theppakulam – feasible Adaptive Transition

5. Need for Adaptive Re-use of Stepwells & Temple Tanks

5.1. Today’s Scenario: Declination & Revival

Although, in today’s world, cities pertain Water Conservation Structures like Rain Water Harvesting Tanks, Over Head Tanks, above and below Ground Levels, the goal is to repurpose wastewater, through reuse and recycling

Various methods of sustainable water supply and management have been in use since ancient times. Understanding ancient practices and strategies offer a framework for considering the present and the future. Ancient water management techniques were able to ensure year-round irrigation and drinking water supply in arid and semi-arid regions. In this review, interesting insights for stepwells and a unique, massive, multifunctional underground water storage system were discussed. While traditional approaches to water management had been focused on ensuring sufficient water supply and sanitation, they do not necessarily reflect sustainable approaches to today’s climate change challenges with global population growth and higher patterns of urbanization. The primary objective of these structures was to entrap rainwater and replenish groundwater level over time. Generally, collected water was recorded to be used by those in the local community to facilitate their sustenance. Most stepwells were observed to be underground structures, designed to form a cool microclimate inside. Hence, stepwells can be the potential nexus node between different water management techniques. Such ancient setups have sizeable potential to be adopted as the foundation for the development of sustainable water engineering solutions. The conservation of existing stepwells through modern sustainable technology along with newly developed infrastructure could address the problems of basic drinking water requirements in India. This approach will not only contribute to the preservation of cultural heritage but also help achieve key sustainable development goals (SDG) and a circular economy. It is important to apply ancient water management techniques to modern societies to integrate traditional knowledge and to explore whether physical and socio-cultural circumstances are comparable for building sustainability and climate-related aridification resilience.

At the end, these stepwells have now become culturally decadent and hygienically unsuitable as they’re being used as spaces for disposing of waste. Plastic bottles, wrappers, and other urban waste can be found lying at the bottom of the stepwells without a masonry base, stagnating in water. After due consideration and analysis of the local culture, climate, environment, social and economic context, revival s.0trategies have been recommended that rejuvenate and retrofit stepwells into modern urban cityscapes. Parks, walking plazas, melas[a] and Haat Bazaars [d] are some of the space design strategies recommended to restore the stepwells.

31

5.2. Strategies for Adaptive Re-Use

By conducting a SWOT analysis, one can judge the effects of revitalizing the Traditional Water Harvesting System structures for an adaptable usage: in Urban or Rural Contexts respectively. The proposals of strategies are driven from an Interview with Architect Rajendran, a Sthapathi [t] based in United States of America, who has been practicing Architectural Restoration and Conservation in India for over 15 years. Particularly, these strategies were resolved in the Rural segments of India to develop them into adaptive developed rural or rather to be called as increased sub-urban zones. Before addressing the solutions, a few conversations with Conservation Architects address the need and necessity of Adaptive Re-use and their perceptions on how it can be executed towards the present-day Indian Context. Below are the basic formulated pointers in strategic usage [4]:

• Adaptive reuse helps in preserving architectural and cultural heritage, which also serves educational purpose of displaying techniques and lifestyles of bygone days.

• Adaptive reuse also helps in providing job opportunities to the local craftsmen and laborers. Since most of the building is already built, the work needed to fit new function requires less money, making them economical.

• These old building are also environmentally beneficial, as they are designed to include natural light and ventilation, thus conserving energy.

• Water buildings will never return to serve as they did, but it is possible to reuse them for a new use, while still preserving the unique typology.

32

Fig 18: Stepwell of Jaipur under Re-Use Strategy for Communal Activities

After numerous discussions with concerning and relevant Architects, namely, Chithra Madhavan, Rahul Ravichandran, and Rajendran, summaries have been enlisted down below: concerning to what extent will Adaptive Reuse solve the current Social-Cultural and Environmental problems in regards to Stepwells and Temple Tanks throughout India.

Comments: The damaging of Stepwells seem to occur due to how locals perceive how to use it… suggesting adaptive re-use and designing per user typology will improvise them.

Inference: Solutions are customized to places as there are different kinds of Social-Cultural Activities per part in India.

Comments: It is high time we document these structures before Nature destructs them for us – Adaptive Re-use requires the in-depth understanding of Cultural Context.

Inference: Each strategy has Strengths and Weaknesses – the conversion of original structures will be challenging

Comments: In my experience, understanding the various Construction techniques and altering them towards our Urban Context is the real challenge.

Inference: The transformation of Structures that were meant for original use – the process might be a difficult execution

33

Conservation Architect Commentary Review Chithra Madhavan, Historian

Architect Ragul Ravichandran, Founder of Vaayil

Architect Rajendran, Sthapathi [t]

Table 8: Commentary from Interviewed Architects on the Adaptive Re-Use of Stepwells & Temple Tanks – presently / previously based in India

With careful understanding of concerns and inputs given from the professional Architects of Conservation – with respect to Traditional Water Harvesting Structures, solutions were discussed and debated to formulate ideas on how to adapt, reuse and rehabilitate these culturally sound, yet recently distinct structures of an urban India. [4]

Strategy Strength Opportunities

Melas [a] (gathering)

· Creates a need for care

· Local Employment Generation

· Improved Social Interactions

· Alignment of Economy

· Historical Value Addition

· Fortification of stepwells

· Organizing festive events

· Generation of revenue

· Feasible Maintenance

Haat

Bazaars [d] (market)

· Will ensure maintenance

· Local employment generation

· Augment local economy

· Historic Value Addition

· Fortification of stepwells

· Organizing festive events

· Generation of revenue

· Feasible Maintenance

Parks

· Prominent feature of the park

· Evaporative Cooling

· Historic Value addition

· Vistas of water landscape

· Retreats of historic worth

· Monitoring Water table levels

· Public Awareness

· Potential to irrigate surrounding

Plazas

Religious Uses

· Cultural Promenade

· Open Air Theater

· Light, Sound Water Shows

· Augment local economy

· Construction of temples

· Spiritual Awakening

· Spiritual Discourse

· Monument for Cleansing

Ritual

· Blending with communal context

· Organizing festive events

· Generation of revenue

· Multi-use areas

· Inclusive gathering space

· Improvise communal harmony

Table 9: (Part 1/2) A SWOT analysis of strategies for adaptive re-use

34

These strategies that propose adaptive re-use of Stepwells & Temple Tanks, by the flow of time, has shown its benefits and effects due to the growth of usage. Addressing the Weaknesses and Threats of the strategies is vital to decide and infer the typologies that are vital for particular Traditional Water Harvesting Systems, respectively. [4]

Strategy

Weakness

Threats

· Lack of initial seed fund

Melas [a] (gathering)

Haat Bazaars [d] (market)

· Increased waste generation

· Safety measures to be adopted

· Absence of governing bodies

· No organized revival

· Threat to water borne diseases

· Increased waste generation

· Safety measures to be adopted

· Absence of governing bodies

· No organized revival

· Threat to water borne diseases

· Destruction due to footfall

· Lack of initial seed fund

Parks

· Management of Surface Water

· Runoff to be ensured

· Absence of governing bodies

· No organized revival

· Threat to water borne diseases

· Lack of initial seed fund

Plazas

Religious Uses

· Increased waste generation

· Safety measures to be adopted

· Absence of governing bodies

· No organized revival

· Threat to water borne diseases

· Separatist attitudes

· Hyenine precautions

· Safety precautions

· Conflict in Communal Harmony

· Threat of water borne diseases

Table 10: (Part 2/2) A SWOT analysis of strategies for adaptive re-use

35

36

Fig 19: Showcasing the problems occurring in Temple Tanks – desecrated parts due to erosion of the Temple Tanks – overgrown Context (Nature taking over buildings)

Fig 20: Ongoing Project of Adaptive Re-Use of a Northern Stepwell / Baori –Mela [a] Proposal

5.3. Conclusion

Stepwells provide a key solution to using water in a sustainable way while preserving the culture and enhancing India’s urban and rural spaces. This study examines the types of stepwells based on their geographic location, functions, craftsmanship and historic significance. The stepwells studied illustrate that they have fallen into disuse as a water resource and almost entirely absent in the historic cultural scene of India. They were found in those regions of India that experience high to extremely high-water stress which reinstates the need for a revival of traditional water storage systems. [12] Therefore, this paper proposes revival strategies that not only conserve them as a heritage water body but also offer a community space which is pointedly lacking in most cities, forcing people to frequent only malls or stay confined to their residential communities. They will prove to be tranquil additions to parks and plazas as well as lively water shows in carnivals. In rural areas, they will sustain the populace with their sanctified water during times of water duress and can play an important role in improving water self-sufficiency.

Reasons of Traditional Water Harvesting Systems Declination:

Urbanization & increased population of the country led to a very fast growth in demand of water. [12] To serve the exceeded demands we looked for faster ways, we went deeper to the ground water level but we forgot to replenish them. Following are the major reasons which caused decline in the traditional water harvesting system:

• During the British Colonization, the whole water distribution system was westernized, central pumping and distribution network was set up which replaced traditional decentralized system.

• Post-independence policy makers never really looked after water harvesting systems and followed the centralized system left by British periods. Lack of innovative ways to deal with water related issues and reliance on big dams, surface transport of water through canals and inter-basin transfers were the main focus area in water policies which neglected the traditional systems.

• Subsidized energized system (Subsidized electrical powers) to exploit deep aquifers which was faster way for the increased demand also left the traditional systems to die.

• As most of the traditional system was community based, villages and towns started seeing a declining interest on the part of community - for nurturing various traditional water harvesting systems was one of the major reasons in rural areas for negligence.

• Some of these tanks were encroached for farming, sand mining, expansion of city, waste dumping, industry, etc.

37

Prepositions:

• Adaptive reuse helps in preserving architectural and cultural heritage, which also serves educational purpose of displaying techniques and lifestyles of bygone days.

• Adaptive reuse also helps in providing job opportunities to the local craftsmen and laborers. Since most of the building is already built, the work needed to fit new function requires less money, making them economical.

• These old building are also environmentally beneficial, as they are designed to include natural light and ventilation, thus conserving energy.

• Once must consider the fact that these Traditional Water Harvesting Structures may never return to serve as they did, but it is possible to reuse them for a new use, while still preserving its unique typology, depending on regions.

In Conclusion, the research points out that over time what Indians called as their special heritage – Stepwells & Temple Tanks were left to degrade and in the present are simply acting as waste disposal or storage areas. [12] This study also stated the need of reviving stepwells as a method to combat the present water crisis in western India. Future research into stepwells and other historical water management structures should focus on the benefits of reviving them for current use and the methods to do the same.

38

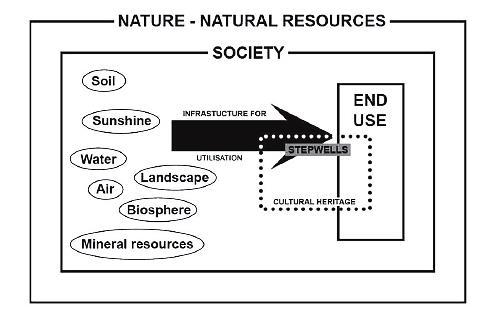

Fig 21: The possibilities of Social-Economic Exploitation of Water as a Natural Resource (Location of Stepwells) – Edited by Wilhelm, 2013

The Way Forward:

“One tank, one temple and a grazing land for cattle of a village was the concept of our ancestors which would support sustainable growth of villages. Water tanks served the following purposes Flood control, prevention of soil erosion, reducing wastage of runoff and recharging groundwater. The management of tanks was given to individuals or to village communities or to temples. Entire tank system was suitable for direct irrigation for agriculture and easy for decentralized water management. These tanks have been constructed using stone, cement or mud or a combination of these.”

- Dr Narayana Shenoy, Jalbharathi

- Dr Narayana Shenoy, Jalbharathi

Today the demand of water is met majorly by withdrawing water from ground water resource causing the depletion of ground water table. Revival of traditional water harvesting systems will help in reducing the major demand of water being withdrawn from ground water sources which is a result of the depletion of ground water table. Using these methods, we can not only fill the gap between water demand and supply but also replenish the ground water table and dried rivers. [12] It requires an individual effort and determination. We need to improvise those traditional methods with available tools and techniques of present times and look forward for a better yield. We can improvise on the construction quality of check dams, water proofing of tanks etc. to save any further water losses from these systems and making them more effective.

Apart from water for our domestic usages of drinking, bathing, cooking, irrigation, there were visual and recreational relations of water with city. Swimming in river, sitting next to a water body and putting leg inside it, morning or evening walk along the water body, weekly markets and gathering near water sources were very popular activities which we miss today. Water bodies are either polluted or not accessible or are dried up Rapid Urbanization has destroyed the pure relation between city and water. By reviving those traditional water harvesting systems, Architects and Urban Designers can try to find a way back to establish the same purity and relation with water which we should have never ignored.

39

Fig 22: Stepwell of Jaipur (An Illustration on Vitality Usage)

I. Glossary

[a] Melas – Communal gathering space; usually, conducting fairs, dramas, gathering of ritualistic baths, multi-day livestock fairs, and annual pilgrim gatherings in Northern India.

[b] Baori – Stepwell Nomenclature in Northern India; long corridor of steps that descend to the water level; present in the subterranean architecture during 7th till 19th Century.

[c] Vaav – Stepwell Nomenclature in Northern India; long arcade of columns driving the user towards the vertical shaft of the Stepwell; has both positive and negative construction techniques; achieved during 7th till 19th Century.

[d] Haat Bazaar – An open-air market that serves as a trading venue for local people in rural areas and towns of Indian subcontinent; conducted on a regular basis thus accumulation of crowd; organized in a varied manner to support or promote providing trading opportunities; meeting places for rural settlers growing into the town culture.

[e] Kalyani – Also called Pushkarni, are ancient Hindu stepped bathing wells. These wells were typically built near Hindu temples to accommodate bathing and cleansing activities before prayer.

[f] Kulam – Wells or reservoirs built as part of the temple complex near Indian temples; sometimes derived from Natural Resources like lakes and ponds

[g] Theppakulam – Main temple tank for a temple town; connects to various Chithrakolam [h] near to the main temple; recharges ground water through surface runoff.

[h] Chithrakolam – Sub temple tank for a temple town; connects to the Theppakulam of the temple town; contains small cubic meters of ground water as parts for recharge purposes.

[i] Kapaleeshwarar – Lord Shiva; combination of two words Kapalam which means head and eswarar which means Lord Shiva.

[j] Karpagambal – Goddess Karpagambal, a form of Shiva's consort Parvati, due to a curse became a pea-hen and did penance here to get back her original personality

[k] Abhishekam – Ritualistic baths; usually taken in a temple tank near to the main temple

[l] Pooja – Ritualistic Practices amongst Hindus in divine spaces of houses and temples

[m] Dravya – Distilled Water; offered by Temple Priests to Worshippers

[n] Theertha – Holy Water offered at Garbhagriha (Main Chamber) of the Main Temple

[o] Panguni – Full Moon Day; annual float festival at large Temple Towns

40

[p] Alangaram – Decoration of Deity of Worship; decorated with flowers and likings of the deity

[q] Neivethanam – Food offering for the Deity of Worship

[r] Deepa Aradanai – Waving of Lamps for the Deity inside the Main Chamber

[s] Pallavas – rulers in southern India originated as indigenous from the Satavahanas

[t] Sthapathi – A Hindu Temple Architect; A Sthapathi must be a designer; builder (sculptor) trained in a number of the arts, sciences (including physics, earth science, etc.); सूत्रधृक्

[u] Kalbelia Dance - males play various traditional instruments and females perform the dance. Kalbelia dance is one of the most sensuous dances among all Rajasthani dances. Kalbelia dance is a folk dance of Rajasthan state of India. It is well known by other names like 'Sapere Dance' or 'Snake Charmer Dance'.

[v] Mihir Bhoj Architecture – Mihira Bhoja (c. 836 – 885 CE) or Bhoja I was a king belonging to the Gurajat-Pratihara Dynasty. He built many innovative ground-breaking structures for his Dynasty.

[w] Dravidian Architecture - Dravidian architecture, or the South Indian temple style, is an architectural idiom in Hindu temple architecture that emerged from South India, reaching its final form by the sixteenth century. It has a pyramidal tower over the garbhagriha or sanctuary called a vimana, where the north has taller towers, usually bending inwards as they rise, called Gopurams

[x] Panguni Peruvizha Chariot Festival - Panguni Uthiram (Tamil:

) is a South Indian Hindu festival and day of importance to Tamils. Panguni Uthiram is a famous festival and special to Murugan, Ayyappa, Shiva and Vishnu devotees. It falls on the day the moon transits in the asterism or nakshatra of Uthiram (Tamil) in the twelfth month Panguni (பங்குனி) of the Tamil calendar. It is the Purnima or full moon of the month of Panguni (

14 March - 13 April)

[y] Therotsavam – Bits and pieces of fallen flowers for the worship of a deity.

[z] Thai Poosam - Thaipusam or Thaipoosam (Tamil:

, taippūcam), is a festival celebrated by the Hindu Tamil community on the full moon in the Tamil month of Thai (January/February), usually coinciding with Pushya star, known as Poosam in Tamil.

[a.1] Mylai Kapaleeshwarar Temple - Kapaleeshwarar Temple is a Hindu temple dedicated to lord Shiva located in Mylapore, Chennai in the Indian state of Tamil Nadu. The form of Shiva's consort Parvati worshipped at this temple is called Karpagambal is from Tamil ("Goddess of the Wish-Yielding Tree").

[b.1] Harshta Mata Temple - The Harshta Mata Temple is a Hindu temple in the Abhaneri (or "Abhaneri") village of Rajasthan, in north-western India. The temple is now dedicated to a goddess called Harshta Mata, although some art historians theorize that it was originally a Vaishnavite shrine.

41

பங்குனி உத்திரம்

பங்குனி

ததப்பூசம்

II. Interviewee Biography

Architect Biography

About:

Chithra Madhavan is an Indian historian. Her area of study and expertise is Indian temple history, architecture, sculpture and iconography. She is the author of eight books on these subjects.

Works (Books):

Chithra Madhavan, Historian

1 - History and Culture of Tamil Nadu: As Gleaned from the Sanskrit Inscriptions, published by D.K. Print World Ltd, 2005

2 - Sanskrit Education and Literature: in Ancient and Medieval Tamil Nadu, published by D.K. Print World Ltd, 2013

3 – Where Ganesha listened to a devotee’s poem – Journal in the Indian Express

About:

Ragul Ravichandran is an Architecture Graduate that works on Conservation, Documentation and Analysis Projects. He is the founder of VAAYIL, a public figure – in search of documenting India’s hidden identities.

Quote: “Vaayil believes in architecture that breathes life. And lasting a lifetime”

Works:

Architect Ragul Ravichandran, Founder of Vaayil

1 – Places – Arikamedu, Panamalai, Mondipalayam, Sivadi, Muddukugalum

Documentation and Analysis for Conservation

2 – Collaborations with SEED from C.A.R.E

School of Architecture

3 – Exploration of Majorly Southern India

Architecture & Design Documentation & Analysis Works

Table (i): 2 out of 3 Interviewee Biography

42

III. Bibliography

[1] Hindu Perceptive on Water by Cardinal Paul Poupard

[2] Hinduism: A Religion to Live – N.C. Choudari

[3] Rig Veda [Original Scripture Translation]

[4] Dewar, David, Watson, Vanessa. Urban Markets: Developing Informal Retailing. London and New York: Routledge, 1990

[5] Madhavi Ganesan, Center for Water Resources, 2008: The temple tanks of Madras, India: Rehabilitation Plan

[6] Viswanathan, Lakshmi. Kapaliswara Temple: The Sacred Site of Mylapore, 2006.

[7] The Forgotten Stepwells: Thousands of Masterpieces in Engineering, Architecture and Craftsmanship provide a window to India’s Past

[8] Stepwells of Southern Rajasthan by Dev Pratap Singh Rathore and K.P Singh Deora

[9] Traditional Water Harvesting Structures and Sustainable Water Management in India: A Socio-Hydrological review by Sayan Bhattacharya

[10] Temple Tanks – the ancient water harvesting systems of Kerala and their multifarious roles by S Maya, 2003

[11] Value Assessment towards Water-related Architectural Conservation: A Qualitative Study of Bundi, Rajasthan – by Ar. Shubangi Kadam and Prof. S.A. Deshpande

IV. References

[12] Stepwells: Reviving India’s cultural and traditional water storage systems. Available at:

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/343127225_Stepwells_Reviving_In dia%27s_Cultural_and_Traditional_Water_Storage_Systems

[13] Selvaraj, T. et al. (2022) “A comprehensive review of the potential of stepwells as sustainable water management structures,” Water, 14(17), p. 2665. Available at: https://doi.org/10.3390/w14172665.

43

V. List of Figures

Fig 1: Stepwells of Ahmedabad: Water Harvesting in Semi-Arid Area

Landscape Architecture Research and Education – TU Delft Faculty of Architecture and the Built Environment Stepwells of Jaipur, Circular Water Stories. https://circularwaterstories.org/analysis/stepwells-of-jaipur/.

Fig 2: Evolution Mapping of Traditional Rainwater Harvesting Systems –where locals convert river streams and Ground water into Architectural Marvels in the early 11th to 12th Century

Delhi sultanate waterworks (no date) Circular Water Stories. Available at: https://circularwaterstories.org/analysis/ancient-waterworks/.

Fig 3: Outline of Temple Tank + Open Stepwell + Closed Stepwell

“Stepwells of Ahmedabad - Exhibition at Yale Architecture.” Aζ South Asia, Anthill Design Ahmedabad, 16 May 2021, https://architexturez.net/doc/az-cf188335.

Fig 4: Clockwise) Typology 2, Cheela Bawadi; Typology 1, Atreya Bawadi; Typology 3, Sarai Bawadi; Typology 4, Bengali Baba ki Bawadi; Typology 5, Parshuram Dwar ki Bawadi.

Landscape Architecture Research and Education – TU Delft Faculty of Architecture and the Built Environment Stepwells of Jaipur, Circular Water Stories. https://circularwaterstories.org/analysis/stepwells-of-jaipur/.

Fig 5: Typologies of Stepwells adapted from Anubhuti Chandna, 2019

Landscape Architecture Research and Education – TU Delft Faculty of Architecture and the Built Environment Stepwells of Jaipur, Circular Water Stories. https://circularwaterstories.org/analysis/stepwells-of-jaipur/

Fig 6: Typologies of Stepwells adapted from Krit Thienvutichai, 2020

Angkor hydraulic city (no date) Circular Water Stories. Available at: https://circularwaterstories.org/analysis/angkor-hydraulic-city/.

Fig 7: Photograph of Chand Baori in 2016

Chand Baori stepwell. India, 2016 (no date) Magnum Photos Store. Available at: https://www.magnumphotos.com/shop/collections/fine-prints/chand-baoristepwell-india-2016/

Fig 8: Photograph of Kapaleeshwarar Temple & Tank from 2009

Kapaleeshwarar Temple (2022) Wikipedia. Wikimedia Foundation. Available at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kapaleeshwarar_Temple.

44

Fig 9: Kalbelia Dance & Langa Singing at the Abhaneri Festival

Holiday (2022) Abhaneri festival - here's what to look forward to, Holiday Holiday. Available at: https://www.holidify.com/pages/abhaneri-festival297.html.

Fig 10: Waving of lamps & Musical Concerts in the Temple

Mylai Kapaleeshwarar temple Panguni Peruvizha festival, Mylapore, Chennai - best & famous shiva temple in India - visit, travel guide (2022) Casual Walker. Available at: https://casualwalker.com/mylapore-kapaleeshwarartemple-panguni-peruvizha-

festival/#:~:text=The%20most%20important%20festival%20observed,then%2 0taken%20around%20the%20temple

Fig 11: Analysis of People & Surroundings over a decade ago

Sowjanya Suresh Follow Working at Edifice Architects & Interior Designers (no date) Dissertation, Share and Discover Knowledge on SlideShare.

Available at: https://www.slideshare.net/sowjanyasuresh/dissertation53862799?from_action=save.

Fig 12: Rajasthan Water System Plan

Landscape Architecture Research and Education – TU Delft Faculty of Architecture and the Built Environment Stepwells of Jaipur, Circular Water Stories. https://circularwaterstories.org/analysis/stepwells-of-jaipur/

Fig 13: Catchment Area of Water – driven from river Cauvery

A: Illustration: Plan & section of the Baoli (source ... - ResearchGate (no date). Available at: https://www.researchgate.net/figure/a-Illustration-PlanSection-of-the-Baoli-source-wwwrebloggycom_fig6_282862274.

Fig 14: Water System Plan for Kapaleeshwarar Theppakulam in Mylapore

Connecting this to an Urban Scale as the Temple Tank is connected to various other small Chithrakolam.

City of 1,000 tanks, Chennai (no date) OOZE. Available at: http://www.ooze.eu.com/en/urban_strategy/city_of_1000_tanks_chennai/.

Fig 15: Catchment Area of Water – driven from Ground Water Recharge & Surface Runoff

A: Illustration: Plan & section of the Baoli (source ... - ResearchGate (no date). Available at: https://www.researchgate.net/figure/a-Illustration-PlanSection-of-the-Baoli-source-wwwrebloggycom_fig6_282862274.

45

Fig 16: Showcasing the Stepwell (Left) Chand Baori & Temple Tank

Explore impressive engineering marvels in India on Engineer’s Day (2022) Kolo Magazine. Available at: https://koloapp.in/magazine/web-stories/topengineering-marvels-on-engineers-day.

Fig 17: (Right) Kapaleeshwarar Theppakulam – preservation of Architectural History through Adaptive Re-Use City, Chennai. “Mylapore Kapaleeshwarar Temple Tank.” Daily Photoblog of Chennai City, https://muthusamy.aminus3.com/image/2013-05-06.html.

Fig 18: Stepwell of Jaipur under Re-Use Strategy for Communal Activities

Landscape Architecture Research and Education – TU Delft Faculty of Architecture and the Built Environment Stepwells of Jaipur, Circular Water Stories. https://circularwaterstories.org/analysis/stepwells-of-jaipur/.

Fig 19: Showcasing the problems occurring in Temple Tanks –desecrated parts due to erosion of the Temple Tanks – overgrown Context (Nature taking over buildings)

et al. (2021) Tamil Nadu: Centuries old temple tank desecrated allegedly by Muslim men, Hindu Post. Available at: https://hindupost.in/dharmareligion/tamil-nadu-centuries-old-temple-tank-desecrated-allegedly-bymuslim-men/.

Fig 20: Ongoing Project of Adaptive Re-Use of a Northern Stepwell / Baori – Mela [a] Proposal

Mehta, R. (2022) Adaptive reuse of ancient stepwells in modern times, Kaleidoscope. Available at: https://www.caleidoscope.in/eco-ideaz/adaptivereuse-of-ancient-stepwells-in-modern-times.

Fig 21: The possibilities of Social-Economic Exploitation of Water as a Natural Resource (Location of Stepwells) – Edited by Wilhelm, 2013

Linkage between ecosystem goods and services and human ...ResearchGate (no date). Available at: https://www.researchgate.net/figure/Linkage-between-ecosystem-goods-andservices-and-human-well-being-UNEP-2005_fig1_275366587.

Fig 22: Stepwell of Jaipur (An Illustration on Vitality Usage)

Landscape Architecture Research and Education – TU Delft Faculty of Architecture and the Built Environment Stepwells of Jaipur, Circular Water Stories. https://circularwaterstories.org/analysis/stepwells-of-jaipur/.

46

VI. List of Tables

Table 1: Listing of Activities in Chand Baori

Table 2: Listing of Activities in Kapaleeshwarar Theppakulam

Table 3: Analysis of Usage & Functionality of Chand Baori

Table 4: Analysis of Usage & Functionality of Theppakulam

Table 5: Material & Construction Comparison between the Case Studies

Table 6: Chand Baori – feasibility in Adaptive Reuse Transition

Table 7: Kapaleeshwarar Theppakulam – feasible Adaptive Transition

Table 8: Commentary from Interviewed Architects on the Adaptive ReUse of Stepwells & Temple Tanks – presently / previously based in India

Table 9: (Part 1/2) A SWOT analysis of strategies for adaptive re-use

Table 10: (Part 2/2) A SWOT analysis of strategies for adaptive re-use