7 minute read

Ag Insight

The U.S. Department of Agriculture has joined other federal and state agencies with steps to deal with the mounting impact of the COVID-19 (corona virus) outbreak. Among other things, the agency has announced:

• An effort with the Baylor Collaborative on Hunger and Poverty, McLane Global, PepsiCo and others to deliver nearly a million meals per week to students in a limited number of rural schools closed due to COVID-19. These boxes will con tain five days’ worth of shelf-stable, nutritious, individually packaged foods that meet USDA’s summer food requirements. The use of this delivery system will help ensure rural children receive nutritious food while limiting exposure to the virus.

Advertisement

• Its Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service, Agricultural Marketing Service and Food Safety and Inspection Service remain committed to ensuring the health and safety of its employees while still providing the timely delivery of the services to maintain the safety of America’s food supply from the farm to the table.

• During unexpected closures, schools can leverage their participation in one of USDA’s meal programs to provide meals to students. Under normal circumstances, those meals must be served in a group setting. However, in a public health emergency, the law allows USDA the au thority to waive the group setting meal requirement; that is vital during a social distancing situation.

Examining food losses at the farm, early distribution stages

It’s no secret that billions of dollars’ worth of food goes uneaten yearly throughout the world. The reasons are numerous, but the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations estimates that 30% of the food loss in North America occurs at the agricultural production and harvest stages.

That finding begs the question: Why would a grower leave food in the field?

Researchers at USDA’s Economic Research Service (ERS) have identified a variety of economic factors that influence growers or distributors in their decisions regarding food loss, including:

• Price volatility;

• Labor cost and availability;

• Lack of refrigeration infrastructure;

• Aesthetic standards and consumer preferences;

• Quality-based contracts; and

• Various policies related to the harvest and marketing of fresh produce.

ERS estimates that $161.6 billion of food at the retail and consumer stage of the supply chain goes uneaten yearly.

While the causes of food loss at the end stages of the supply chain have been well studied, the causes of loss on the farm and in early distribution stages have not. Food loss as it relates to fresh fruits and vegetables is especially challenging because these foods are highly perishable.

New team targets beginning farmers

USDA is launching a new team of personnel that will lead a departmentwide effort focused on serving beginning farmers and ranchers.

“More than a quarter of producers are beginning farmers,” said USDA Deputy Secretary Stephen Censky. “We need to support the next generation of agricultural producers who we will soon rely upon to grow our nation’s food and fiber.”

To formalize support for beginning farmers and ranchers and to build on prior agency work, the 2018 Farm Bill directed USDA to create a national coordinator position in the agency and state-level coordinators for four of its agencies – Farm Service Agency (FSA), Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS), Risk Management Agency (RMA), and Rural Development (RD).

Sarah Campbell has been selected as the national coordinator to lead USDA’s efforts. A beginning farmer herself in Maryland, Campbell held previous positions with USDA and has worked on issues impacting beginning farmers and ranchers.

In her new role, she will work closely with the state coordinators to develop goals and create plans to increase beginning farmer participation and access to programs while coordinating nationwide efforts on beginning farmers and ranchers.

“We know starting a new farm business is extremely challenging, and we know our customers value and benefit from being able to work directly with our field employees, especially beginning farmers,” Campbell said. “These new coordinators will be a key resource at the local level and will help beginning farmers get the support they need. I look forward to working with them.”

Each state coordinator will receive training and develop beginning farmer outreach plans tailored to their state. Coordinators will help field employees better reach and serve beginning farmers and ranchers and will also be available to assist beginning farmers who need help navigating the variety of resources USDA has to offer.

To learn more about USDA’s resources for beginning farmers, as well as more information on the national and state-level coordinators, visit newfarmers. usda.gov and farmers.gov.

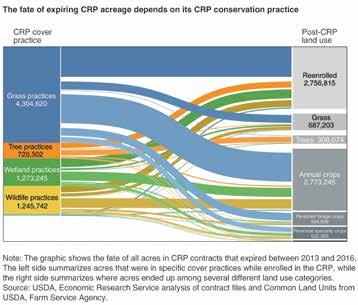

What happens to land that exits CRP?

A study by USDA’s Economic Research Service shows most land that exits the Conservation Reserve Program (CRP) has been put into some type of crop production.

Administered by USDA’s Farm Service Agency, CRP is the largest land retirement program in the nation. Under the CRP, landowners voluntarily retire environmentally sensitive cropland for 10 to 15 years in exchange for an annual rental payment.

Once a CRP contract expires, land may be offered for re-enrollment, subject to the availability of signup opportunities. And the acreage enrollment cap allotted to the program did in fact decline between 2007 and 2016, reducing re-enrollment opportunities by 13 million acres.

To answer the question of what happens to CRP land when a contract ends, ERS studied the fate (as of 2017) of 7.6 million acres of expiring CRP land between 2013 and 2016. That acreage amounted to approximately one-quarter of all CRP acres enrolled at the end of fiscal year 2012.

Overall, about 36% of expiring CRP land (2.8 million acres) was re-enrolled in the program. Of the 4.9 million acres that exited the program (i.e., were not re-enrolled), about 81% were put into some type of crop production — with the remainder going into grass, tree and other nonagricultural covers.

Trade policy differences continue

While the coronavirus pandemic has pushed the U.S.-China trade dispute out of the spotlight, differing views on what is, or is not, happening, continue to prevail.

On one hand, USDA officials have touted that China has taken numerous actions to begin implementing its agriculture-related commitments under the U.S.-China Phase One Economic and Trade Agreement on sched ule. The agreement took effect in mid-February. These actions include:

• Signing a protocol that allows the importation of U.S. fresh chipping potatoes;

• Lifting the ban on imports of U.S. poultry and poultry products, including pet food containing poultry products;

• Lifting restrictions on imports of U.S. pet food containing ruminant material;

• Updating lists of facilities approved for exporting to China;

• Updating the lists of products that can be exported to China as feed additives; and

• Updating an approved list of U.S. seafood species that can be exported to China.

In addition, USDA says China has begun announc ing tariff exclusions for imports of U.S. agricultural products subject to its retaliatory tariffs and has an nounced a reduction in retaliatory tariff rates on certain U.S. agricultural goods.

Officials say these actions will facilitate China’s progress toward meeting its Phase One purchase commitments.

Meanwhile, Minnesota wheat and soybean farmer Tim Dufault summed up his reaction to the Trump ad ministration’s trade war with China at a recent House Ways and Means Committee hearing.

“We are now … two years into a trade war that we were told would be good and easy to win,” Dufault testified.

“Time and again, we have been told to hold out for a deal that would make all the pain worth it. And while you would be hard-pressed to find a farmer who would disagree with the fact that China has been a bad actor, farmers have shouldered the pain for a strategy that has seen only one minor tariff reduction and several tariff escalations.”

Dufault, who represented the group Farmers for Free Trade as well as himself, was among several speakers assessing the effect of the trade war and the first phase of a new trade agreement that calls for Chi na to buy $80 billion more in U.S. agricultural products over two years.

“The purchases, which have not yet materialized, are a promise while the tariffs are real,” Dufault said, stressing the rising number of farm bankruptcies in Minnesota and several other states. “The ag economy doesn’t live on promises. Until China buys, we are not buying the promise.”