T H E M AG A ZIN E OF T H E A L AS K A HUM A NIT IES FO RUM

S P RING / SUMMER 2014

Whittier: A City Under One Roof | Alaska’s Lost Modernist Master | Tent City Fiction

LETTER FROM THE CEO

The Impact of the Humanities A

161 East First Avenue, Door 15 Anchorage, Alaska 99501 (907) 272-5341 | www.akhf.org

s the CEO of the Alaska Humanities Forum, during the last year one word repeatedly came to mind: invigorating. I continue to be inspired by my remarkable Board and dedicated Alaska Humanities Forum staff, as well as our vital partners who help us to deliver our programs across the state.

board of directors Joan Braddock, Chair, Fairbanks Ben Mohr, Vice Chair, Eagle River Catkin Kilcher Burton, Secretary, Anchorage Evan D. Rose, Treasurer, Anchorage Dave Kiffer, Member-At-Large, Ketchikan

The Olympic Games: Through the Lens of the Humanities

I’ve had the honor of attending seven Olympic Games, both as an athlete and an official member of the United States delegation. However, the 2014 Sochi Olympic Games was the first Olympics that I attended as the CEO of the Alaska Humanities Forum. I found the Sochi Olympic Games to be as much about the celebration of the humanities as it was athletic excellence. One personal interaction reminded me of how the Olympic Games are uniquely intertwined with the humanities. I worked with a Russian volunteer during my time in Sochi. I asked him if he’d taken vacation to volunteer. He responded that his vacation request was not approved, so he quit his job in Siberia and drove 2,000 miles to offer his time and perspective. “Someone like me only has one chance in a lifetime to do something like this,” he said. “I have the opportunity to show my country’s culture, people and history to the world. How could I have not come?” His passion reminded me why all of our humanities programs are so very important in creating a bridge for crosscultural understanding here in Alaska as well as on the international stage.

Our Programs in Action

I recently had the opportunity to join our Take Wing Alaska (TWA) Program project team for a site visit to Toksook Bay in Eastern Alaska. The TWA

2

ALASKA HUMANITIES FORUM

Jeane Breinig, Anchorage Christa Bruce, Ketchikan

Nina Kemppel President & CEO

Lenora Lolly Carpluk, Fairbanks Michael Chmielewski, Palmer

Program supports Alaska Native high school students from rural communities to transition to urban post-secondary education opportunities, with the long-term vision for them to return and contribute to their home communities. My trip to Toksook Bay was designed as a recruiting mission for the next cohort of TWA students. However, the visit was a much more meaningful trip than I ever expected. During my stay in Toksook Bay, I had the opportunity to experience the celebration of the first seal of the season. It was an honor to be invited to attend this traditional ceremony where seal meat and other important items for a family dinner were given out to all of the female members of the community. I wish to thank all of the Toksook Bay participants for their generous hospitality.

John Cloe, Anchorage

Thank You to Donors

Gregory Moses, Take Wing Alaska Family School Liaison

I personally thank all of the donors who have contributed to the Alaska Humanities Forum over the last year. We are focused on developing new and innovative programs that serve our state, and your donations are helping us to strengthen and evolve our programs here at the Forum.

A L A S K A H U M A N I T I E S F O R U M S P R I N G / S U M M E R 2014

— Nina Kemppel, CEO

Dermot Cole, Fairbanks Ernestine Hayes, Juneau Joshua Herren, Anchorage Scott McAdams, Sitka Elizabeth Moore, Kotzebue Pauline Morris, Kwethluk Wayne Stevens, Juneau Kurt Wong, Anchorage

STAFF Nina Kemppel, President & CEO Susy Buchanan, Grants Program Director Kitty Farnham, Leadership Anchorage Program Manager Megan Zlatos, Office Manager Matthew Turner, Special Projects Coordinator Veldee Hall, RURE Sister School Exchange Project Manager Carmen Davis, C3 Project Manager Nancy Hemsath, RCCE Program Associate Nate O’Connor, Take Wing Alaska Project Coordinator

Carmen Pitka, Take Wing Alaska Family School Liaison

FORUM MAGAZINE STAFF Editor David Holthouse Art Director Dean Potter Contributing Writers Christina Barber, Susy Buchanan, Deb McKinney, Patti Moss, Katherine Ringsmuth

T H E M AG A ZIN E OF T H E A L AS K A HUM A NIT IES FO RUM

S P RING / SUMMER 2014

Frederick Machetanz

FORUM 40

22

LOREN HOLMES

4 The Far Side of the Tunnel

Forum grantee Jen Kinney documents Whittier

14 Lost Master

The legacy of Alfred Skondovitch

20 Intentional Community

Leadership Anchorage alumni launch coworking space

22 Instinct and News Sense

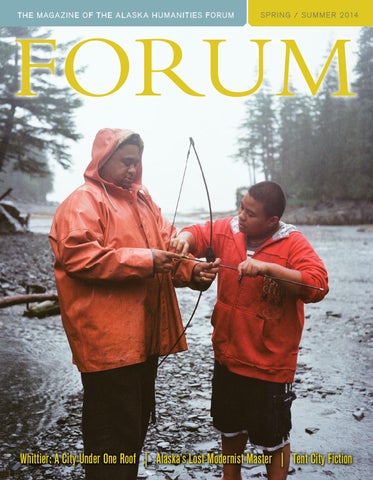

COVER “ Ti and Demitrius.” Photographed in Whittier by Jen Kinney. See page 4.

47

Forum is a publication of the Alaska Humanities Forum, supported by the National Endowment for the Humanities, with the purpose of increasing public understanding of and participation in the humanities. The views expressed by contributors are not necessarily those of the editorial staff, the Alaska Humanities Forum, or the National Endowment for the Humanities. Subscriptions may be obtained by contributing to the Alaska Humanities Forum or by contacting the Forum. No part of this publication may be reproduced without permission. ©2014. Printed in Alaska.

A conversation with photojournalist Loren Holmes

28 Museum on Main Street

Smithsonian Institution’s “Key Ingredients” Alaska tour

30 Valuing Exploration Alaska Humanities Forum 2014 general grants

36 Between Earth and Heaven

Excerpts from A Land Gone Lonesome by Dan O’Neill

ANCHORAGE CENTENNIAL

40 Diamonds from Wilderness America’s pastime in the Last Frontier

45 From Camp to City

Anchorage Centennial Legacy Media Projects

46 Augmenting History

Digital storytelling and historical reconstruction bring Centennial history alive

47 Paid in Kind

Tent-city fiction by Kris Farmen, presented with Augmented Reality features

56 Celebrating a Century

Forum awards first round of Anchorage Centennial Community Grants

The Far Side of the Tunnel Forum grantee Jen Kinney embeds in Whittier to document a city under one roof

By Debra McKinney

ennifer Kinney was a New York City college student with a summer break coming when she learned of an opening at a seafood cafe in a small coastal town in Alaska. Alaska sounded perfect, especially for a writer and photography major drawn to faraway places. Kinney accepted the job over the phone, knowing nothing about this place called Whittier. “I didn’t think to look it up until a day before I got there.”

She boarded a plane in early June 2011 and four time zones later landed in Anchorage on a gray, drizzly night. Her handlebar-mustached boss, whose work uniform would consist of raucous chef’s pants, a tied-dyed apron, suspenders and a baseball cap, met her at the airport, accompanied by a large, curly haired dog that reminded her of a cross between a poodle and a walrus.

4

A L A S K A H U M A N I T I E S F O R U M S P R I N G / S U M M E R 2014

He tossed her bags into the back of his pickup and headed straight for the first in a collage of images that come to mind when Kinney recalls her introduction to Alaska — Walmart. She had just a few minutes to dash in and grab basics. They had to make it to Portage not one second past 10:45, before the tunnel into Whittier shut down for the night, sealing off the town from

More than half of Whittier’s year-round population of approximately 200 live in Begich Towers, a 14-story high-rise built for officers stationed in Whittier during the Cold War. Jen Kinney

car traffic. Blasting down Turnagain Arm, Kinney remembers marveling at the seasonal light, seeing her first glacier in Portage Valley, being swallowed by Maynard Mountain as they entered the single-lane tunnel, then 2.6 miles later being spit out the other side into a tantrum of sideways rain and otherworldly fog. “That was my very first Alaska

experience, and it now seems very authentic,” said Kinney, now 23. “It was surreal… and disjointed, and hard to understand how these things all fit together. “Turns out it was right up my alley.” Whittier, she discovered, wasn’t anything like she’d imagined, not the quiet, lonely hamlet where she’d get some solitude for a change. Not in summer, A L A S K A H U M A N ITI E S F O R U M S P R I N G / S U M M E R 2 01 4

5

The Sound of Prince William By Jen Kinney

[Ed. note: This article is excerpted from A City Under One Roof, a work in progress supported by grants from the Alaska Humanities Forum and the Center for Documentary Studies at Duke University through the Dorothea Lange– Paul Taylor Prize.]

A NOTICE TO OUR READERS The Sound of Prince William has endeavored to follow the policy of reporting the events that happened along this end of Prince William Sound in the manner in which they occurred. The method of telling it may be in an off-beat fashion and at times even corny. But the report is coming from an offbeat location and unbelievable people and events. […] It is not necessarily our intentions to be comical. It is just the only way we know how to tell it. We do not try to cover world events, nor State of Alaska happenings, because of our unusual geographic location, our inaccessible means of reaching the outside world – no television, very poor radio reception and week old newspapers. Therefore we must make our own news. —The Sound of Prince William, January 1973

T

he story of Whittier’s transformation from a military base strategically located in one of the most hostile environments to man in South Central Alaska to a ghostly town that a ragtag team of hermits, runaways, and otherwise upstanding citizens banded together to purchase begins in 1960, with the sudden departure of the U.S. Army from the port it had just spent 20 years and $55 million dollars to build. By that year the port had seen the construction of three major projects—the railroad tunnel that linked it to the interior and the Hodge and Buckner Buildings, the two largest structures in the Alaska territory. Two million tons of military supplies had arrived by barge and left by rail. So it came as a surprise to company clerk Al Waltz when he received news in September of the port’s pending inactivation. His final morning report that December tallied 156 military men remaining on the dwindling base, a far cry from its peak population of 1,200. The closure of the port still baffles Waltz. In 1960 the Cold War had the world in its frigid grip. Vinyl 45s in the Buckner’s music room played “Big Bad Nick,” a kiss-off to Russian leader Nikita Khrushchev. Whittier’s last large construction project had been completed only four years prior. Alaska had just become a state in 1959 and freight was still rolling into port until the military began diverting it to Seward and Anchorage in

6

anyway, with its influx of seasonal workers who come to fish, staff the cannery, clean hotel rooms, serve up food, crew on tour boats and otherwise tend to the 700,000 cruise-ship passengers and other assorted visitors passing through town. Not with residents living beside, beneath or on top of each other, most in the 14-story Begich Towers Incorporated, or the BTI as locals call it. Although it wasn’t obvious to her at first, this town that was named after a glacier that was named after a poet was exactly what Kinney needed. Once she acclimated to its claustrophobic confines and tempestuous weather, the people and the place captivated her. She returned to New York that fall to wrap up her degree in photography and imaging at New York University’s Tisch School of the Arts and to deliver its student commencement address on the need for collaboration and community in the arts. The following summer, she was back in Whittier. And the summer after that. “After graduation I thought, ‘What do I want to do with this degree, what do I need to learn?’ Whittier had been such an interesting experience for me. I couldn’t stop thinking about it.” Now she’s embedded. Backed by a $7,500 grant from the Alaska Humanities Forum, Kinney is living, working and giving back to her new community while collecting photographs, stories, oral histories and archival materials for a documentary project she’s calling “City Under One Roof.” Her final product will be a book that weaves these elements together. The title is a moniker borrowed from the Buckner Building, built by the military in the early ‘50s to withstand bombs. In addition to housing personnel, the Buckner’s amenities included a small hospital, barbershop, mess hall, library, radio station, rifle range, photo lab, church, officers’ lounge, theater, bowling alley, bakery, commissary and jail. As a 273,660-square-foot, self-contained building, there was little need to step outside, and when one arose, tunnels connected it to other facilities. Once the largest building in Alaska, the Buckner is now a hollow, concrete phantom, a Cold War relic that overlooks the town through its dark, vacant, busted-out-window eyes.

The “city under one roof” was abandoned decades ago, but the metaphor fits. Whittier’s year-round, winter population would leave nearly half the seats of a 747 jumbo jet empty. Small, but that’s upward of 200 personalities, from recluses to social butterflies, altruists to egocentrics, born-agains to dedicated partiers, almost all of them neighbors living in the BTI or the two-story Whittier Manor. As long-time resident Terry Bender put it to Kinney: “We all live in the same house, we just have separate bedrooms.”

“Whittier magnifies what people are about” said Brenda Tolman, artist, sign painter, notary public, gift shop owner, reindeer enthusiast and Whittier resident since 1982. When she arrived shortly after her sister Babs, she said Whittier was full of possibility and entrepreneurship as people came who were intrigued by the opportunity to construct a town from the dilapidated former base. Jen Kinney

A L A S K A H U M A N ITI E S F O R U M S P R I N G / S U M M E R 2 01 4

7

advance of the closure. In the last days when shipments had all but stopped, Waltz had occupied himself by agitating crows from the windows of the near-vacant Buckner. His roommate, however, was kept mighty busy, using a bulldozer to raze orphaned equipment into the water. Bits of scrap metal, twisted rails, cars without serial numbers, an M60 tank that no one could say for certain was supposed to be coming or going: all were sunk to rust. Materials had come to the farflung territory at great expense and would have to leave in the same costly manner. In the final weeks anything the town could afford to lose was buried at sea. When it was done, the army walked out, leaving behind a skeletal maintenance crew and a gleaming white elephant. This was the city inherited by a civilian population of 40 people. The railroad was the only land route in or out of the base, but without a military population it ran intermittently with no schedule or timetable. The 60-mile trip from Anchorage to Whittier could take nearly 8 hours. Two expensive and nearly new buildings stood empty. The 1964 earthquake damaged both mildly and, in concert with the subsequent tsunami and fire, killed 13 people, destroyed the lumber mill and oil tank farm that employed most of the civilian population, and left the port contaminated by oil and creosote. In 1968 the base’s assets were transferred to the U.S. General Services Administration, a move that the 1984 Whittier Comprehensive Plan described as “tantamount to abandonment, as without maintenance or protection, the buildings rapidly deteriorated from weather damage and vandalism.” This did not deter intrepid residents of the former base and future town. A rotating population slowly rebuilt the tank farm and continued port operations. By 1969, Whittier boasted roughly 70 homespun citizens. They incorporated that year as a fourth-class city. Incorporation was only the beginning of their trials. The infrastructure was in place, but it was already decrepit. A government would have to be built from scratch. Three years after incorporation Whittier’s first newspaper, The Sound of Prince William, rolled off the press. It affords a hilarious and heartbreakingly sincere glimpse into the daily lives, personal histories, and grandiose dreams of the first curious souls drawn to the newborn city. The Sound of Prince William, edited by tank farm employee Jim Berry, sported headlines like “Are Residents of a Second Class City Second Class Citizens?” and “Is Whittier Too Proud to Die?” Impertinently, with tongue firmly in cheek, it described a town where mail arrived just twice a week and sometimes a month late; where your neighbors were apt to nail your door shut or paint your dog green; where your every activity, from heading to town to falling in love, was fodder for the bristling “Social Column.” “This is your chance to get in on the act of helping develop a city from scratch,” the front page of every paper declared beneath its motto: “You haven’t seen anything until you have seen Whittier.” Many of the first challenges the town faced still plague it today. Citizens wanted to build a road to Shotgun Cove so that a new town site could be developed there, far from the industrial center. They wanted a larger small-boat harbor. Most essentially, they sought to acquire property owned by government

8

Since its conception, Whittier has been a curiosity. Walled off by mountains, with its front door opening to the sea, the site was chosen by military strategists for its ice-free, deep-water port, fist-like mountainous grip, dependable cloud cover and fog as thick as cotton balls — ideal for hiding from enemies. It’s a place where houses with yards don’t exist, bears get into the garbage and snow loads collapse roofs and sink boats in the harbor. Deserted by the military in 1960, incorporated as a second-class city nine years later, Whittier has seen more than its share of trouble for its age — abandonment, fires, floods, a killer earthquake and tsunami. And ridicule. “So many people come here and write crap about this place,” said Bender, who’s included in Kinney’s mosaic of stories. “People come here and just don’t get it. They talk to some drunk at the bar and think we’re all drunks who live here because we can’t live anywhere else. “I stay here because the place talks to me. Not in words; I’m not crazy or anything. I just get this really great energy. It’s so beautiful here. You either get it or you don’t.” Kinney, she said, gets it. “Just the fact that she’s stayed here and wants to get it right. I honestly think the place talks to her, too.” Kinney could have grabbed some stories and photos that first summer, called it good and moved on. She could have turned her project into her senior thesis. But her interests go beyond the surface, because the Whittier she knows is complex and often misunderstood by people from the other side of the tunnel. And she had no desire to be one of those. “They [Whittier residents] are really used to the portrayal of their town as super weird and super broken,” she said. “I wanted to see what it felt like here after two months, three months, six months. I thought it was really important, first from a trust angle, and second, from a depth angle, not go off on first impressions. People have told me expressively, ‘I don’t trust anyone who hasn’t been here for a winter.’” So this time around, she’s staying a year to continue her work in progress. Driving up the Alaska Highway last summer to begin her full-immersion assignment, doubt

started seeping in. She knew Whittier had a remarkable story to tell, but would others see its worth? She was partway up the Alaska Highway she got her answer. She learned by phone that she’d won the $10,000 Lange-Taylor Prize from the Duke University’s Center for Documentary Studies, given to those carrying on the tradition of acclaimed photographer Dorothea Lange and writer/social scientist Paul Taylor, for projects centered around the interplay of images and words.

With wind that can gust up to 80 miles per hour and annual snowfall that has reached more than 55 feet, it is easy not to leave Begich Towers for days or weeks. Jen Kinney

A L A S K A H U M A N ITI E S F O R U M S P R I N G / S U M M E R 2 01 4

9

agencies and the Alaska Railroad. In 1973, they did just that, using a $200,000 bond to purchase the town site and seven buildings—including the Hodge and the Buckner—from the General Services Administration. Arguably, the sale marked the high point of Whittier optimism. Bennie Barker, the town’s second mayor, told the Anchorage Daily News that the town would convert the Hodge Building into condominiums, with a 15th floor restaurant and cocktail lounge, and the Buckner Building into a hotel, ski lodge and commercial hub. Even more audacious was the proposal, two years later, to turn Whittier into a carless town. Visitors would leave their cars on the other side of the tunnel and float through town via alpine tramways. Throughout the years, the Sound of Prince William played cheerleader, advocate and provocateur. In 1972, the paper boasted that beneath Whittier’s careless exterior one could find “Two Theaters, Café, Swimming Pool, Gift Shop, Watering Hole, and Grocery Store.” In 1973, it reported on the Whittier vs. Whittier lawsuits about election propriety and voting rights that threatened to divide the young city squarely in two. In 1974, a competition was held to rename the Hodge Building—prompting such entries as “Little Alcatraz” and “Poverty’s Ridge”—and the citizenry rolled up their shirtsleeves to repair the newly christened Begich Towers’ earthquake-damaged interior. That same year, the town librarian and newspaper editor carried on a debate, issue after issue, about prohibiting neon lights. The librarian feared that Whittier might become “a carbon copy of Las Vegas or New York City” unless it banned their use and became instead, “Whittier, Alaska, the City with the advantages of civilization, but without its blight.” The editor countered by quoting Genesis, and off they went, as surrounding articles jested about the faraway scandals of the energy crisis, of Watergate, of the Vietnam War. Year after year, the same advertisement ran for the Sportsman’s Inn, which reigned with shabby courtliness as the only restaurant in the young township. Beneath a thickly penned illustration of a hotel with rickety beds and gusty holes in the wall, the Sportsman’s boasted its “ROOLS AND REGULATIONS”:

1. NOT MORE THAN FOUR GUESTS IN ONE BED ESPECIALLY IF LADIES ARE PRESENT. 2. PLEASE REMOVE BOOTS BEFORE RETIRING. OUR SHEETS BECOME RATHER SOILED BEFORE THE MONTH IS OVER. 3. NOT MORE THAN FIVE GALLONS OF ALCOHOL ALOWED IN THE ROOM, PER PERSON THAT IS. The Sportsman’s was a textbook Alaska menagerie of enterprise: there was a laundry and general store in the basement, a restaurant and bar above, and hotel rooms out back. By the mid-70s, Ross and Irma Knight owned the joint, which had morphed over the years through different owners and a hodge-podge of uses. Irma was a German woman transplanted in Alaska, a one-armed, nationally rated skeet shooter who never had a hair out of place. Irma’s couture was immacu-

10

Equipped with notebooks, a digital audio recorder and two vintage, mediumformat cameras, Kinney’s work is a study of Whittier’s history, people, politics, structures, economy, culture and selfimage. It’s an exploration of freedom and confinement, of detachment and community. She’s documenting how the town changes with the seasons, and the role the tunnel plays in keeping “enough of the world out to let silence, clarity and introspection in.” She’s particularly intrigued by the influence physical spaces have on people’s lives, and vice versa. “That’s really the crux of the Whittier story,” she said, “how that’s evolved over time.” It doesn’t hurt that Whittier is awash in colorful stories, many of which are actually true. Like the fellow, stewed to the gills, who got cut off at the bar and returned later armed with a mean cat, threatening to throw it in the bartender’s face. And recipients of the annual “Toilet Seat Award,” established in honor of a woman who got so trashed one night she got sick, losing her dentures down the toilet in the process. Esteemed winners include the man who backed into the town’s only police car and the BTI resident on his way to the bathroom one morning who instead ended up in the hallway locked out of his apartment, naked, about the time kids were heading out for school. So there’s that. But, as Kinney points out, Whittier is also the kind of community where no one is homeless, no one goes hungry and people look after each other whether they like each other or not, especially when the absurd weather hits and life becomes dicey in a hurry. In that regard, Whittier is a writer’s and photographer’s paradise, bestowed with stories that send Kinney down “a rabbit hole,” as she calls it, as one story leads to the passageway of another. Why people come, why they stay, what they find there they haven’t found anywhere else. Still, she knew winter wouldn’t come easy, watching businesses shutter, friends leave and the town empty out at the end of the season. “It got colder and quieter,” she said.

“Having come from a big city there was this feeling of dread. It was hard going through the shortening of the days. It’s like the tunnel, you’ve got this darkness narrowing in on you from all sides.” She got busy, though. She settled in, first in the BTI, then the Whittier Manor, then back in the BTI. She got certified as an emergency medical technician and is now on call for the volunteer fire department two days a week. She started volunteering at the school. She attended

Annie Shen and husband Joe have operated the Anchor Inn, bar, restaurant and general store since 1979. “When I first got here, I hated it. So dark and so dead in the winter,” she said. But then her husband climbed a mountain pass and looked down Passage Canal to where it connects to Prince William Sound and beyond to the Pacific Ocean, eventually lapping up on their native Taiwan. “For him, it was like hope,” she said. Jen Kinney

A L A S K A H U M A N ITI E S F O R U M S P R I N G / S U M M E R 2 01 4

11

late; she preferred color-coordinated outfits and silk blouses, which didn’t stop her from scooping elbow deep in a drum of ice cream. Her personal propriety didn’t extend to the establishment. When the Health Department tossed expired meat from the restaurant’s freezer into the dumpsters out back, Irma waited for the inspectors to split town on the next train and then ordered her crew to haul the meat back in, wash it off with vinegar, and load it right back in the freezer. It was the Sportsman’s that brought Babs Reynolds to Whittier in 1978, when she responded to an ad at the Anchorage Employment Center for a chambermaid and waitress. A train happened to be heading to Whittier that very afternoon. A veteran bartender, the Sportsman’s was the only job she was ever fired from. The customers didn’t like her. It was no matter. Babs stayed, opened her own hamburger stand, and wrote her sister to come up too. Whittier was a sanctuary, whether Babs got along with her neighbors or not. “Most of us were on the run in one way or another,” she said. “Bad debt. I had an abusive ex-husband. We were looking to do something different, like live,” she barked in smoky laughter. “Who else can say they live in a town where they close the doors at night?” Whittier was an easy place to live, if you could accept the downsides. Rent was cheap. The law was enforced just passably. But by the time Babs moved to town, the sheen of optimism had been tarnished, and the Sound of Prince William had already met its demise. Barker had been overthrown as mayor in a series of nasty legal battles that dragged through 1975. Opponents had him ousted for missing three meetings after Whittier reverted to a city manager form of government. Stripped of his salary, he sought work on the fledgling pipeline. The mayor sued. When voters took to the ballots to recall the ousters, a second lawsuit brought their voting rights under attack. The rift went deep. For eight months the press went silent: the new council had pulled the plug on the city-funded, pro-Barker paper. When Berry managed to raise the funds to revive it, The Sound of Prince William returned with a different voice. Gone were the editorials waxing poetic about the limitless possibilities of life and commerce on Prince William Sound. Gone was the front-page illustration of a man chasing another man straight out of his pants before a backdrop of a dilapidated cartoon city. The jokiness remained, but the bitterness was unmistakable. Where before the greatest ire was reserved for the unreliable Alaska Railroad, now the paper turned against its citizenry. Berry wrote of the council he considered selfserving and divisive; of the $150,000 debt still unpaid from the town’s purchase; of the city managers the city just couldn’t seem to retain long enough to continue the progress started by the first three councils. The early positivity had sailed on airy dreams. Now, Berry asked, where is that road to Shotgun Cove? What became of the progress he’d been drumming up for the past four years? By the end of the decade, Berry was gone himself. Whittier had always been a town of transplants and transients, from the construction crews to the fishers, from the military to the here-today-gone-tomorrow residents, whose only common ground was their willingness to claim that title. ■

12

church, workout sessions and city council meetings. And she’s covering Whittier for the Turnagain Times. The reporting gig is proving to be a valuable litmus test for her documentary project, since her neighbors are more than willing to weigh in on how she’s doing. “If they have a problem with (a story), they tell me on the elevator. It’s really good for them, and for me. I’m held very accountable for the things I write.” Since that first summer, she’s worked as a server, a barista, a deck hand, a fish processor, and now a reporter. This summer she’ll be working as a kayak guide. By immersing herself in all things Whittier, she’s getting to know its possibilities, as well as ways to ward off boredom. She’s learning what it takes to keep the town safe, powered up and navigable when snow piles so deep it covers windows and barricades doors, and raging winds do their best to knock the place down a size. “I grew up in a (Connecticut) suburb, and never in my life thought about what it took to run a municipal government,” she said. “The more I’ve been here, the more I’ve become interested in community development.” Ted Spencer, executive director of Whittier’s Prince William Sound Museum, appreciates Kinney’s efforts. “She’s not just running around poking her camera at stuff and blasting away; she is working at her craft,” said Spencer, a past Alaska Humanities Forum grant recipient. “She’s an artist. Her written prose is eloquent and carefully crafted. “I very much admire Jen’s energy and creativity. She is combining her talents, education and love of adventure to capture a rare moment in the life of a small Alaskan community. These works of art and written observations will constitute the historical records that will be examined and appreciated by the generations that come after.” Now watching spring unfold from the ninth-floor of her BTI apartment, her computer parked at the window, she’s come to appreciate what others appreciate about Whittier in winter, the way it feels safer when the weather and the tunnel team up to create a moat. In winter, people can leave doors unlocked and keys in the ignition. Parents know their kids are safe. If a man drops his wallet, he can be relatively certain it’s going to make its way back to

him. Not so with the comings and goings of summer. Living in Whittier, Kinney says, is teaching her many things, not the least of which is what it means to be part of a community — a city under one roof. “You really learn how to get along together, how to talk to each other,” she said. “Somehow it works. Sometimes it doesn’t work as well as it could, but there is this something we share, and what we share is living here.” ■

The only land route in or out of Whittier is the 2.6-mile, single lane tunnel at the end of this staging area. In 2000 it was converted from railroad to mixed automobile and railroad use. Some residents blame a decline in community engagement on the increased ease of access. Jen Kinney

A L A S K A H U M A N ITI E S F O R U M S P R I N G / S U M M E R 2 01 4

13

‘As I embark on the last paintings of my life, I bow to Alaska and the happiness she has brought me.’ – Alfred Skondovitch, 2010

“Spirits After Torture” david belisle photo

Lost Master T h e l egac y o f Alfre d S ko n d ov i tc h BY PATTI MOSS

I

t may come as a surprise to many Alaskans that an obscure Fairbanks painter named Alfred Skondovitch, who died in 2011, once stood shoulder to shoulder with the greatest American artists of the 20th century. For a time he was recognized on par with Willem de Kooning, whose paintings hold the record for the highest price ever paid for American works of art. Several of Skondovitch’s closest New York colleagues went on to become giants of the postwar Modernist Period of American art. The painter Mark Rothko named their group “The New York School.” Some artists in the New York School emerged out of the poverty of war in Europe. Others edged up through the complex political scaffolding around the New York gallery and art museum world. In 1947, Alfred Skondovitch joined them at the age of 20 when he jumped ship in New York Harbor with a letter of referral to famed abstract expressionist Franz Kline stuffed in his pocket. Skondovitch soon found a place at the school in Provincetown, Massachusetts, run by the legendary artist and teacher Hans Hoffman, who played a key role in the abstract expressionist movement. The school was a Mecca for postwar artists. Hofmann lectured on theory to packed rooms. Among the attendees were many new immigrants. Skondovitch’s journey had already been long and grueling; but in many ways, it was just beginning.

Alfred Skondovitch in New York in 1956, around the time of the famous “Ten American Painters” exhibit which included work by Willem de Kooning. courtesy david belisle

A L A S K A H U M A N ITI E S F O R U M S P R I N G / S U M M E R 2 01 4

15

Alfred Skondovitch was born and raised in London by Russian Jewish immigrants. As a youth he was sent to the English countryside during the London Blitz, and there he was exposed to great paintings in grand countryside estates. Near the end of World War II he went to France as a teenager. He worked odd jobs, helped his older brothers promote boxing matches, and assisted in efforts to arrange the underground transport of Holocaust survivors to Israel. He also painted, as he had since the age of nine. While living in France as a young man, Skondovitch had a life-altering experience when he visited the BergenBelsen concentration camp in northern Germany with a Zionist youth group. They encountered the same horrific scene as other liberation witnesses: the barely living encamped among the dead. The youths were unable to help and retreated. What he witnessed at Bergen-Belsen emblazoned itself upon Skondovitch’s psyche and would emerge decades later in his most magnificent work. After Bergen-Belsen, Skondovitch entered a London art school where he was noticed for his exceptional ability. He received a letter of recommendation from an instructor who was the sisterin-law of Franz Kline and soon left for America by taking a job as a deckhand on a cargo steamer. In New York Harbor, he simply jumped ship in order to avoid customs. In the immediate postwar years, U.S. immigration had swelled; visas had become very difficult to obtain, especially for Jews. Skondovitch was too impoverished to await the process, and he entered the country on the run. Within a handful of years, in a meteoric rise, Skondovitch was exhibiting his abstract expressionist paintings in New York’s finest galleries and was widely considered to be among the best of a movement of painters who became modern art masters. The New York Times art critic Dore Ashton acknowledged Alfred Skondovitch paintings above those by Willem de Kooning in her review of his work. He took part in

16

the landmark 1956 abstract expressionist exhibit, “Ten American Painters,” widely considered the most prestigious exhibit of abstract expressionist paintings in history. Then suddenly, at the brink of incalculable opportunity, Alfred Skondovitch walked away from it all, and eventually spent decades painting quietly in Fairbanks before passing away three years ago at the age of 84. A few years before his death, Skondovitch’s wife discovered in his small Fairbanks studio more than 70 richly colored paintings of dreamy figures floating in Chagall-like worlds. They are his legacy, the Holocaust Paintings. The paintings are not sad, but filled with intriguing brightness and alluring hues where figures engage the viewer through a thick silence. All are emotionally political, and seem to portray a mysterious visitation from figures out of a soft, deep, dreamlike world. There is nothing outwardly grim in the figures. They’re simply messengers. In one large painting, a clown hangs from a gallows in brilliant hues usually seen in children’s books or watercolors of flowers. “Hanging Clown” wears a clown costume. His neck is bent. His brightly colored outfit wilts on his frame, yet his expression is smirking. He has been hung for misbehaving. Was he a betrayer, a camp legionnaire, a kapo (prisoner functionary for the SS)? The clown reappears here and there among the other figures in the series. Who are they? Skondovitch wisely allows the figures to tell their own stories. He does not intrude with obviousness but allows us to journey through the questions each of us carry about the Shoah. A jester extends his arm enticing naive children to follow. He was, Skondovitch reported, the betrayer inside the altered reality of the camps: the collaborator, the snitch, the prisoner too slow on his feet to avoid damnation; and perhaps, the outside world silent in knowing. Other figures sit in quiet repose. Yes, in some of the paintings there is death. In most, there is eternal connection, dialog, conversation, pondering and knowing, from the viewer and from the figure.

A L A S K A H U M A N I T I E S F O R U M S P R I N G / S U M M E R 2014

Then suddenly, at the brink of incalculable opportunity, Alfred Skondovitch walked away from it all.

Alfred Skondovitch in his Fairbanks studio in 2010. david belisle

The Holocaust Paintings stands with the greater body of Skondovitch’s paintings of nudes, figures and abstracts. It would be a mistake to define his work by the Holocaust Paintings alone, as his masterful images of figures magnetize and engage with great depth. He began the Holocaust Paintings at the beginning of the 1980s. What compelled him is not certain. Only a few people knew what he was working on toward the end of his life. At one point he allowed the small Jewish community in Fairbanks to exhibit two of the paintings. He led a weekly sketch group that had met regularly for many years, exhibited in modest Alaska venues, and was invited to speak to the art history class at University of Alaska Fairbanks taught by Kesler Woodward, Professor Emeritus of Art History at the University of Alaska Fairbanks. He captivated students by

lecturing on art theory and his experiences as an artist. The reasons around Skondovitch’s abrupt departure from the New York art world in the late 1950s remain murky. During his few years in New York, he struggled at times to keep a room or get a meal; at other times, he generously helped others. When broke, he reported later, he would nurse a cocktail for an entire evening at the Cedar Bar, a Greenwich Village watering hole that served as a salon of sorts for artists and writers of the period. There he socialized with those who would go on to become legends, including de Kooning and Rothko. He hung around with the great poet Frank O’Hara, who worked as a security guard at the Museum of Modern Art, and who allowed Skondo-

vitch to crash at his place when he could not afford rent. According to Skondovitch, during his years in New York, he also befriended the poet Dylan Thomas, who was struggling with severe alcoholism. Later, during his own struggle with depression in his first years in Fairbanks, Skondovitch would express remorse for having been drinking with Thomas and others in late 1953 when Thomas collapsed and later died. This was one of many stories from his days in New York that Alfred Skondovitch shared only with his wife Patti. During those years, Skondovitch was part of a small circle of friends trying to survive on bummed meals and handouts at the same time their art was gazed upon by the wealthiest residents of the city. The circle included Andre Malraux, Wolf Kahn, Franz Kline, Rothko, Robert De Niro, Sr., and Elaine and Willem de Kooning. Abstract Expressionism was objected to and politicized by the American art community. Its legitimacy was hotly debated. Major arts philanthropists took sides, including Nelson Rockefeller, who refused to support abstract expressionist artists at the Museum of Modern Art (MOMA), even though his wife was the director of acquisitions for 20 years. (After she resigned he gave $20 million to MOMA to purchase the same artists she had promoted.) Dogged by immigration authorities, Skondovitch avoided gallery openings because he was afraid of being arrested. Openings are bad luck anyway, he reasoned. Not long after the “Ten American Painters” exhibit at the Poindexter Gallery, Skondovitch agreed to do a favor for well-known gallery owner and art dealer Elinor Poindexter by delivering a shipment of important paintings to a gallery in Texas. He wrecked the truck and all the paintings were destroyed. Poindexter assumed he had been drunk; and furiously denounced Skondovitch in a remark that he was “probably the best” painter rising in the New York ranks, but he was blowing it. According to Skondovitch’s wife, Patti, he wasn’t drunk at the time of the crash. He simply did not how to drive. (She taught him how to drive years later

A L A S K A H U M A N ITI E S F O R U M S P R I N G / S U M M E R 2 01 4

17

in Alaska.) After the accident, Skondovitch stayed for a while at a friend’s house in Texas, pondering his next move. He did not return to New York. Instead, he headed west, leaving paintings hanging at the Poindexter Gallery, and untold numbers of others in closets and back rooms of studios and apartments across the city. Skondovitch first went to California, where he used another referral to get into the art department of Claremont Men’s College (now Claremont McKenna College). As part of an artists’ group at Claremont, he made money building Hollywood movie sets during the academic term and then joined the artists in going to Fairbanks in summer to fight wildfires. During his third summer in Alaska, Skondovitch married Patti Howard, who’d grown up in Fairbanks. For their honeymoon, he used his meager savings to take her to Paris, and then onto Vallauris, a town in southeast France where Pablo Picasso was creating magnificent large sculptures. In Vallauris, Skondovitch trekked up the hillside above the village to Picasso’s gated villa. On the first morning, he was simply told to go away. The second day, there were many black limos in the driveway, so he did not approach the gate. On the third morning, a caretaker dismissed him, then called him back. Yes, he could see the Maestro, but only if he needed to urinate. Puzzled, Skondovitch followed the man to the patio where Picasso stood above a large clay sculpture of a ram. “So you will piss on it. I am dry,” said Picasso. So Alfred did. A moment later a woman drove into the driveway, got out and began screaming toward Alfred and waving her arms. She was yelling for him to leave. A bit taken back by it all, he made his retreat back down the hill to tell Patti what had happened. Nearly 40 years later, Skondovitch encountered the screaming woman again during a conference at the University of Alaska Fairbanks. She was Francoise Gilot-Salk, who had been Picasso’s mistress and later married Dr. Jonas Salk. In Fairbanks, she delighted in Skondovitch’s recalling the day they had originally crossed paths so long ago and far away.

18

“Snow Princess” david belisle photo

Alfred and Patti Skondovitch returned from their honeymoon to settle down in Fairbanks. During their first decade together in Alaska, he managed various businesses. He occasionally had small exhibits. But he also began experiencing a sense of longing whenever the New York art scene rose up in his mind, which happened with the arrival of each edition of Art News, the major arts magazine. His wife reflected on this time, “One time he was reading the latest edition of Art News and he looked so sad, so I said, ‘Okay, let’s give it a try.’ And we went to New York to see what would happen.” In New York they spent three months in the sweltering heat of summer, visiting old galleries which were now in new hands, looking up Wolf Kahn and a handful of other artists from the old days, and becoming more and more distressed as the toe hold they had hoped to find proved elusive. At the end of summer they returned to Alaska. Instead of being emotionally fatigued by the experience in New York, Alfred Skondovitch seemed to embrace their return to the north. It was as if, Patti recalled, he had made some sort of emotional switch. The depressive episodes

A L A S K A H U M A N I T I E S F O R U M S P R I N G / S U M M E R 2014

failed to reappear. He was happy. “He was the funniest person I ever knew,” Patti once remarked. His friends helped build a studio in their yard. Alfred filled it with bright lights and painted to his favorite Fred Astaire musical pieces. He started a sketch group and taught a few classes here and there between working regular jobs. Patti worked for an airline and they had two children. “I hardly ever went in the studio except to tell him he was wanted on the phone or that supper was ready,” she said. A few years later Skondovitch had a one-man show at the State Museum in Juneau. Over the years his work was collected by a handful of followers, including two generations of the Klatt family. (Upon discovering his work one day in an Anchorage gallery, the Klatts drove to his house in Fairbanks after not being able to reach him by telephone. There they found Alfred clipping the hedge in front of his house. It was the beginning of years of support and friendship.) Toward the end of his life, Skondovitch had exhibits at Fairbanks artist David Mollett’s gallery. He also worked with The Museum of the North, on the acquisition of perhaps the most important of his Holocaust Paintings, “Hanging Clown.” UAF

“Hanging Clown” david belisle photo

Museum of the North curator Mareca Guthrie conducted a series of detailed interviews with Skondovitch. Graduate students in art history cut a path to the Skondovitch home. Since his passing, Patti and their daughter, Lara Duke, have managed Skondovitch’s estate and worked toward preserving his place in American art history, especially the legacy of the Holocaust Paintings. Patti met Alfred when she was a young beauty and he was a humble summer firefighter visiting Alaska. She fell in love with a forest worker, not a painter. When asked of Skondovitch’s place

“Erin” david belisle photo

in Alaska art, UAF professor emeritus Kesler Woodward said that Skondovitch never conceded to be an Alaskan painter. “He [Skondovitch] painted figures, which do not have a place in Alaska art as abstract expressionist figures,” said Woodward. “His work was always outside of Alaska art. He was focused solely on what he desired to paint, which was primarily the figure.” What do the Holocaust Paintings by Alfred Skondovitch mean to the world? What place will his work find among the renowned paintings of his colleagues in the New York School of American Modernism? In an art world teeming with

venture capitalists investing in modern art masters, the answer may still be coming. In the curatorial realms, Alfred Skondovitch is a footnote in bold font, rising toward a higher place on the pages of history. ■ Alfred Skondovitch’s work can be found at www.skondovitch.com Alaskan historian and writer Patti Moss may be reached at pmmoss@yahoo.com. Photographer David Belisle (davidbelisle.com) has recorded R.E.M. and other rockers. He was a close friend of Alfred Skondovitch.

A L A S K A H U M A N ITI E S F O R U M S P R I N G / S U M M E R 2 01 4

19

LEGACY OF LEADERSHIP ANCHORAGE

Intentional Community Leadership Anchorage alumni launch coworking space

T

he single-day purchase record for the Seattle IKEA store was set last October by two Leadership Anchorage alumni. Katherine Jernstrom, 30, and Brit Szymoniak, 27, prefer not to reveal exactly how they much the spent. But here’s a clue: the receipt was six feet long. Together with a collection of mid-century designer furniture they picked up at vintage stores during their five-day spree in Seattle, the women loaded the IKEA boxes into a 26-foot U-Haul truck, the largest that’s legal to rent without a commercial driver’s license. They then began a three-day journey up the ALCAN Highway. Things did not go smoothly at the Canadian border crossing. “The customs officials had a few questions for us,” said Szymoniak. And so the close friends and co-founders of The Boardroom explained, once again, their concept for Alaska’s first “coworking” space, a creative nexus where self-employed professionals can “work independently in a collaborative environment.” The furniture, they said, would outfit the 6,000-square foot space, scheduled to open for business the following month. The border guards made them post a $500 bond and sent them on their way. As IKEA shoppers are well aware, assembly is required. Upon arriving in Anchorage, Jernstrom and Szymoniak hosted a marathon furniture building party. Fueled by pizza and beer, they and a group of

20

A L A S K A H U M A N I T I E S F O R U M S P R I N G / S U M M E R 2014

Leadership Anchorage alumni and The Boardroom cofounders Katherine Jernstrom (left) and Brit Szymoniak.

friends gradually assembled enough stylish furniture to fill a standard office room wall-to-wall, floorto-ceiling, with empty cardboard boxes (they were recycled). The Boardroom, located on the second floor of the Key Bank Plaza on Fifth Avenue in downtown Anchorage – prime real estate – opened last November and now is the base of operations for more than 30 small businesses and self-employed professionals, including website developers, attorneys, food truck operators, and photographers. Coworking began in San Francisco roughly a decade ago. It’s since become a global movement, with more than 700 coworking spaces in the U.S.

BOTH BRIAN ADAMS

‘We both knew a lot of freelancers who were tired of having business meetings in espresso bars.’ — Katherine Jernstrom

Freelance photographer Josh Martinez at work in The Boardroom.

alone. The concept is to create a collective work space described in one popular online video as “accelerated serendipity,” a space where “freelancers can bounce ideas off of small business owners, entrepreneurs can inspire corporate refuges, and fledgling startups can quickly build a diverse social network.” Jernstrom and Szymoniak came up with the idea for launching a coworking space in Anchorage after they met and became friends in 2011 as fellow members of the fifteenth cohort of Leadership Anchorage, the Alaska Humanities Forum’s premiere leadership development program. At the time, Jernstrom was the community outreach director for Bean’s Café, and Szymoniak was the Port of Anchorage’s director of public affairs. “We both knew a lot of freelancers who were tired of having business meetings in espresso bars at four in the afternoon,” said Jernstrom. The rise of the coworking movement is driven by the ongoing fundamental shift in the U.S. labor force away from traditional full-time jobs in favor of freelance and temporary contract work. There are currently about 42 million self-employed workers in the U.S. – about 30 percent of the nation’s workforce – according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. That percentage is projected to rise to 40 percent by 2019. To help them determine whether they should quit their jobs and roll the dice, Jernstrom and Szymoniak conducted market research that indicated the demand

in space in U.S. cities can support one coworking space for every 85,000 residents. “We decided that if coworking is so popular in Seattle and San Francisco and New York, then why not here,” said Szymoniak. “And if why not here, then why not us?” Membership at the boardroom ranges from $150 a month for two days a week of business hours access to the open, shared work space, up to $500 a month a for limitless access. Private offices are $900 a month. Collaboration and networking is encouraged but not required. “We don’t force people to sit down and work together,” says Jernstrom. “We provide the opportunity for collaboration through the intentional, meaningful design of space.” Sugarsled Creative owner David Taylor, a branding consultant, joined the Boardroom in January. “Just being around all the entrepreneurial energy of the place, my productivity immediately shot up,” he said. “Everyone there is excited, and motivated. I’d been working from my home office for about two years. It was lonely and un-inspiring by comparison.” Taylor said it’s a welcome change to be able to invite clients to his place of work. “It [The Boardroom] makes me look good. It’s a beautiful space,” he said. “And let’s face it: I’m a high-end, high-paid professional. It was time for me to stop telling clients, ‘Meet me at the coffee shop.’” ■

A L A S K A H U M A N ITI E S F O R U M S P R I N G / S U M M E R 2 01 4

21

Instinct & News Sense A conversation with Loren Holmes By David Holthouse

T

he photography of Loren Holmes rides its own line between fine art and photojournalism. Consider, for example, the slideshow of his photos published May 2 by the online news publication Alaska Dispatch, where Holmes has been the one-man photo department since early 2012. The previous morning, two Alaska State Troopers had been killed in the line of duty in Tanana. Within hours of the shootings, Holmes was on the ground in the isolated Yukon River village, 130 air miles west of Fairbanks, photographing a standoff between heavily armed troopers and the father of the alleged murderer. The slideshow skillfully captured the breaking news with daytime photos of law enforcement officers in tactical gear surrounding the house where the

22

man was barricaded, then taking the suspect into custody after he surrendered. But accompanying these traditional news images were a series of photographs made by Holmes just before and after sunset. The photos are devoid of people. They show an empty bench and chairs overlooking the frozen Yukon River, a battered traffic cone affixed with crime scene tape, and the dark silhouette of the steeple of the village church set against barren trees and purple light fading to darkness. In context, these atmospheric images carry a powerful emotional resonance that transcends basic news photography, illustrating the mood of a small town in the twilight between shock and grief. A native of Anchorage, Holmes is the only child of an archaeologist and anthropologist. He studied philosophy

A L A S K A H U M A N I T I E S F O R U M S P R I N G / S U M M E R 2014

before graduating with a master’s degree in photography from Ohio University’s School of Visual Communication. Perhaps best known in Alaska and elsewhere for his impressive photos of the Iditarod Trail Sled Dog Race in recent years, Holmes is about to join the combined photo staff of the Alaska Dispatch and the Anchorage Daily News, following the Dispatch’s purchase of the state’s largest newspaper. The acquisition, announced in early April, alters the media landscape of Alaska. The week before the Tanana shootings, Holmes visited the Forum offices to discuss the logistics of covering the Iditarod and the influences and reasoning driving his unique approach to photojournalism. What follows is a transcript of that conversation, edited for length and clarity.

India’s a visual treat. This photo was taken on a Sunday drive with a family that had taken me under their wing. LOREN HOLMES

Why did you study philosophy? I took a year off between high school and college, because I didn’t think I was ready to really focus on school. I traveled for a year by myself around the world. Started in Japan, worked my way west to Hong Kong, Singapore, Nepal, India, Switzerland, Germany, France, Netherlands. My mom did the same thing when she was 18. She got a job washing dishes on a Norwegian freighter and wound up crossing the Indian Ocean, so I kind of got the idea from her. When I came back to the US, I still didn’t know what I wanted to study, but I decided that philosophy was basic to anything and everything. To life.

Do you have a favorite philosopher? I’d have to say John Rawls. [Ed. Note: John Bordley Rawls was an American philosopher and a leading figure in moral and political philosophy.] He came up with the idea of Just War theory. When it’s right to engage in war. The idea of a just war was something I’d never considered before I studied his work—the ethics of war, that there is a right way and a wrong way to wage war, and that war, while terrible, is not always the greater evil.

Do you believe that having studied philosophy influences your photography? Yes. Philosophy makes you think about things differently. It makes you think about them more critically. That applies photography. When you think critically you take more time, you question your own assumptions, and that definitely influences your photography.

A L A S K A H U M A N ITI E S F O R U M S P R I N G / S U M M E R 2 01 4

23

This photo of Jeff King was from this year’s Iditarod. He’s passing by the cliffs outside Ruby, the first checkpoint on the Yukon river for the northern route. The Iditarod is such a challenge to photograph year after year. I’m always trying to come up with new ways to keep it fresh, to find a different perspective on the same scenario. But the Ruby cliffs always seem to make the cut. They’re just so stunning.

24

When did you become serious about photography?

Did you return to Alaska after getting your master’s degree?

What led you to start working for Alaska Dispatch?

I’ve been interested in photography for as long as I can remember. When I was in high school I had a mentorship with the photo department at the Anchorage Daily News. This was 1997 or 1998, back when they still had a darkroom. They were still developing film. They’d just gotten their first digital camera, a Nikon D1, and they were experimenting with it, but they were still using film almost exclusively. I was photo editor of my college newspaper, the Carletonian, at Carleton College in Northfield, Minnesota. After I graduated, I came back to Alaska, thought about it for a while, decided photography was definitely what I wanted to do, and went to grad school.

No, I taught in India. I spent five months in a rural area near Bombay. I started a photography project at a college where I introduced students to photography. We had five point-andshoot digital cameras. I would come up with a weekly assignment, and they’d go out and shoot, and we’d look at photos and talk about composition. I came out of it really impressed with what they had done. They didn’t have a lot of creative outlets, so they really embraced the concept and took photography to heart.

After teaching in India, I came back to Anchorage, waited tables for a bit, then got a job at a stock photo agency in Girdwood. Mostly I was selling other peoples photos, doing a little bit of my own shooting to fill holes in the archive. The hour commute each way got old. So I decided to try to make it freelancing. I shot some weddings, shot some stuff for the New York Times, the Associated Press. Then in 2012 I got a tip from somebody who said the Dispatch was looking for someone to shoot the Iditarod, and right after the race the Dispatch hired me. Up until late last year, when we hired a videographer, I’ve been a one-man photo department.

A L A S K A H U M A N I T I E S F O R U M S P R I N G / S U M M E R 2014

BOTH LOREN HOLMES

My editor at Alaska Dispatch, Mike Campbell, had a hunch that this guy Matt Novokovitch was about to win the Mt. Marathon race. So he sent me over to make a photo of his customized treadmill. He modified it so it would go up to 40 degrees, way steeper than a normal treadmill. And he was so hardcore, he would only train going up, not up and down like most other people who were training on real mountains. But he won that year.

What’s your logistical strategy for shooting the Iditarod?

Do you have any favorite spots for shooting the race?

Before we shoot the Iditarod, before we go out on the trail, we sit down and sketch out what we think might happen. We look at the historical run times between checkpoints and where certain mushers typically take their rests, and we do our best to map out a game plan, factoring in where we want to spend the night, and when we want to be in certain places. We based this year’s plan on the last two years, but our plan went out the window pretty quickly because they basically did the race a day faster, so we lost a day. I’m extremely fortunate to have a publisher who flies her own plane, and flies us around to cover the race. It’s our plane, so it’s easy to adjust on the run.

I like the Dalzell Gorge. [Ed. note: A particularly notorious two-mile stretch between Rainy Pass and Rohn.] It’s really narrow, really windy, has lots of tight turns, and the dogs are coming down very fast. When I shoot in the gorge, I carry two cameras, one with a wide angle lens and the other with a telephoto, then I set up a third camera with a remote control about 100 yards or so up the trial from where I position myself, so that I can shoot the mushers and dog teams from that angle as well. A lot of mushers were coming out of Dalzell Gorge really banged up this year. A lot of broken sleds. I actually caught DeeDee Jonrowe’s dog team in

the gorge, without her on the sled. Her dog team came by, dragging the sled on its side, then a few minutes later, she came walking down the trail, by herself, holding the brake that had come off in her hand. Another of my favorite places on the Iditarod is further down the trail in Koyuk, a checkpoint that’s right where the dog teams come off the sea ice. Usually, they come off the ice right at sunrise, so it makes for some beautiful photos.

A L A S K A H U M A N ITI E S F O R U M S P R I N G / S U M M E R 2 01 4

25

In Kerala, India, I spent some time with the fishermen there. It’s a very local fishery, they go out in boats, most much smaller than this one, pull in nets by hand, and sell what they catch at the local fish market. Most people I talked with said that the fishing wasn’t very good after the 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami.

26

What kind of cameras and lens do you prefer?

How do you recognize the moment to capture?

There’s nothing really special about the gear. I use Canon cameras. 5D Mark IIIs. I do use a 24 1.4 lens which lets me shoot in the dark a little better. I like to shoot before sunrise, after sunset, I like to push the boundaries of the light. But really, the camera is just a tool. The lens is just a tool. At the Daily News they all use Nikons. It doesn’t really matter. It’s whatever you’re comfortable with, whatever you’re proficient in using, so you can capture the moment in the most aesthetically appropriate way.

Instinct. Instinct, and a sense of the news. I would like to consider myself an artist, but that’s not really appropriate, because at heart I’m a journalist. My first responsibility is to record the facts in front of me. That’s photojournalism in the purest sense: you record facts in the form of a photograph. But I always try to tap into the power of art photography by trying to generate an emotional response with my photos. For me, doing my job right means not only giving you the facts, but also making you feel something based on how I visually present those facts. That may not be a common in photojournalism. But it should be.

A L A S K A H U M A N I T I E S F O R U M S P R I N G / S U M M E R 2014

Do you identify yourself more with newspaper or magazine photography? I look at what I do as closer to magazine than newspaper in that I’m trying to broaden the audience. I don’t assume that my audience is just people in Anchorage or just people in Alaska. I assume it’s somebody in New York or Florida or Germany. I want to make photos that are compelling to them, as well as Alaskans, and that speak to the issue more broadly than something as local as what you might typically see in a newspaper.

BOTH LOREN HOLMES

Alex DeMarban and I got to Kaktovik the day after they pulled in the whale. We wished we’d arrived a day earlier, but they’d worked all through the night, and left the head because they just didn’t have time to get to it. It’s on the beach, right next to the village. They were cutting up this giant piece of meat and in the distance you could see polar bears. It was a little unnerving. They’d just be working away, cutting up the whale meat, and polar bears would start walking up the beach toward us, and whenever a bear got a little too close, one guy just got on his four-wheeler and drove straight at the bear, ran it off.

‘Doing my job right means not only giving you the facts, but also making you feel something based on how I visually present those facts.’

How do you feel about shooting for online versus print? There’s a lot more freedom shooting for online publication. You don’t have the same kind of deadline pressure. If I need another hour to wait for the light to be perfect, I can do that. I also have more space online, so I shoot a lot of slideshows, whereas in print it’s often one photo, maybe two. It’s easier to tell complete stories with pictures online, because you can use more pictures.

As the Daily News and the Dispatch combine operations, will you be shooting for newsprint as well as the website? I’m excited about it, because it’s basically doubling the size of the newsroom. More reporters means more stories, means more photo ideas. I’ll be shooting for both. I’m looking forward to being part of a photo department, and having a photo editor, because I’ve been my own photo editor, and I think every photographer can benefit from another set of eyes on their photos. ■

— LOREN HOLMES

A L A S K A H U M A N ITI E S F O R U M S P R I N G / S U M M E R 2 01 4

27

Museum on Main Street Forum coordinates Smithsonian Institution’s “Key Ingredients” Alaska tour “Cooking is like love. It should be entered into with abandon or not at all.” — Harriet Van Horne

A recipe from the Key Ingredients exhibit at the Pratt Museum.

28

O

n a crisp, blue-sky day in early April in Homer, 19 black crates arrived from Washington D.C. Bearing cargo stickers from all over the U.S., the travel cases contained a selection of Smithsonian Institution artifacts, photographs and illustrations about something that is so basic to human existence, so important in cultural development, and often so delicious — food! Staff from the Smithsonian Institution, the Alaska Humanities Forum, and the Pratt Museum in Homer unlatched the travel crates to assemble the exhibit, “Key Ingredients: America by Food” (Key Ingredients). Key Ingredients arrived in Alaska for an eight-month tour. The exhibit is part of the Smithsonian Institution’s Museum on Main Street (MoMS) pro-

A L A S K A H U M A N I T I E S F O R U M S P R I N G / S U M M E R 2014

gram, and will be visiting four Alaska communities, Homer, Palmer, Talkeetna and Fairbanks. It will be featured in each location for two months. The role of the Alaska Humanities Forum is to host, coordinate and oversee Key Ingredients though its Alaskan tour from April to November this year. One-fourth of all Americans live in rural areas, and one-half of all U.S. museums are located in small towns.Museum on Main Street is an outreach program aimed at bringing Smithsonian-quality museum experiences to rural communities and helping to unite the nation by giving visibility to the cultural traditions and interests of rural America. Key Ingredients examines how culture, ethnicity, landscape and tradition have influenced the foods and flavors we enjoy across the nation. In collaboration with the Smithsonian, each participating institution will provide a complimentary exhibit that incorporates its own geographic location, history and traditions. Throughout each exhibit, local artists, historians, scholars and members of the community will share their stories and creative works. This is an exciting opportunity for communities to explore the connections between the Alaskan identity and the foods we produce, prepare, preserve, and present at the table, as well as a provocative and thoughtful look at the historical, regional and social traditions that merge in daily meals and celebrations. Key Ingredients examines the evolution of the American kitchen and how

food industries have responded to the technological innovations that have enabled Americans to choose an everwider variety of frozen, prepared and fresh foods. Each participating community in Alaska will showcase its particular food culture, and host outreach activities such as inviting locals to share oral histories of harvesting and preserving food, offering lectures by humanities scholars on the history of cold storage (e.g. Dena’ina Athabascan food cache pits and homemade ice boxes of the first homesteaders), and providing information on sustainable gardening, climate change, and educational information on nutrition. Alaska is characterized by cultural richness and diversity. Despite the active and dynamic artistic population, Alaska faces challenges when it comes to making exhibits and creative opportunities accessible. Key Ingredients will travel to communities along the road system. The four selected communities, Homer, Palmer, Talkeetna and Fairbanks, have a combined population of approximately 44,000 people. The Forum expects that working with entities in these communities will provide an opportunity for their residents along with those of surrounding communities to participate in Key Ingredients, thus increasing the potential creative and educational impact of the exhibit in Alaska. The communities and partnering institutions were selected through a competitive application process and the selected institutions were chosen for their focus in highlighting art, history, anthropology and science within the scope of their missions. These institutions include The Pratt Museum in Homer, The Palmer Museum of History and Art, Northern Susitna Institute in Talkeetna, and The University of Alaska Museum of the North in Fairbanks. Through Key Ingredients, Alaska has an opportunity to break bread with the rest of the nation, and bring its unique cuisine to the table, and in this way contribute and honor traditional foods, from all Alaskans. The exhibit is currently on display

at the Pratt Museum in Homer. From there it will move to the Palmer Museum of History and Art. The Alaska tour of Key Ingredients was made possible by the sponsorship of Conoco Phillips, the Rasmuson Foundation, the Alaska State Council on the Arts and the Alaska Humanities Forum. â–

A 1949 cookbook cover in the Smithsonian traveling exhibit Key Ingredients.

Christina Barber is the Key Ingredients Alaska tour manager for the Alaska Humanities Forum.

A L A S K A H U M A N ITI E S F O R U M S P R I N G / S U M M E R 2 01 4

29

Valuing Explora Alaska Humanities Forum 2014 general grants Panoramic view of the mouth of the Karluk River and Karluk Village, on the northwestern tip of Kodiak Island, ca. 1960. For more than 30 years, the Karluk One archeological site (located on the small peninsula in the background, below the church) has provided beautifully preserved artifacts to fuel the Kodiak Alutiiq heritage movement. A Forum grant will support publication of a book exploring the 600-year-old site and its contents to build a picture of prehistoric Alutiiq life. Alutiiq Museum archives, Clyda Christiansen collection, AM680.

30

A L A S K A H U M A N I T I E S F O R U M S P R I N G / S U M M E R 2014

ation

W

ho are we? What do we believe? What connects us across cultures, and what sets us apart? Where have we been, where are we going, what do we value, and why? The humanities seek answers to such questions by studying human traditions, ideals, history and actions. This year the Alaska Humanities Forum is proud to support 15 projects in the humanities throughout the state with general grants totaling $64,120. The projects are geographically and conceptually diverse, ranging from a documentary film about homelessness in Anchorage to permanent exhibits of poetry in Lake Aleknagik State

Recreational Area near Dillingham. They include a book of Alutiiq artifacts from a Kodiak archaeological site and a float trip down the Koyukuk River, so that Koyukon Athabascan elders can point out and teach the names of places to village youths in their first language. The projects have in common a free exchange of ideas. They share the same basic quest for wisdom. What follows are summaries of each of the projects supported by Alaska Humanities Forum 2014 general grants. They are listed alphabetically by project title, followed by the name of the project director or sponsoring organization, the location of the project, and the grant amount.

A L A S K A H U M A N ITI E S F O R U M S P R I N G / S U M M E R 2 01 4

31

Brief Stories in Time: Equinox in Rural Alaska will mentor young people from across Alaska in crafting a story from one day in their community: the Spring Equinox, March 20, 2015. The stories will come from all regions of Alaska. Students will draw inspiration from traditional Alaska Native storytelling practices while learning from experienced artists and journalists about how to gather and report information in print and broadcast media. Art shows in each participating community will feature stories from the area, and a First Friday art opening at the Alaska Humanities Forum will showcase selected submissions. The goals of this project are to inspire students in rural Alaska to illuminate the Alaska Native experience from across the state while developing skills in journalism and reporting, and to find out what could happen if young storytellers are empowered to communicate their visions of their communities, even if just for one day. The Coldest Winter Mark Wilcken • Anchorage • $3,000

The Coldest Winter is the working title for a feature-length documentary film about homelessness in Anchorage. This grant supports the initial research and development phase of the film, which aims to profile a handful of the city’s approximately 4,000 homeless residents as they attempt to survive a winter on the streets. The concept is to interview several homeless individuals in Anchorage in late summer/early fall, then chronicle the challenges they face in the following months of cold, ice and darkness. Running parallel to these profiles will be interviews with police officers, aid workers, shelter volunteers, and others on the front lines of this slow-motion tragedy. The Coldest Winter project director is Arkansas-based filmmaker Mark Wilcken, who won three regional Emmy awards in 2012 for Clean Lines, Open Spaces, a film about the construction boom in the United States post-World War II.

32

Crosscurrents Southeast: A Confluence of Writers and Readers 49 Writers • Craig, Juneau, Sitka, Ketchikan • $4,710

Building on the success of its 2013 Crosscurrents programs in Barrow and Kodiak, 49 Writers is expanding its beyond-the-roads literary workshop series to four communities in Southeast Alaska. The project brings together two of Alaska’s premiere authors, Ernestine Hayes (Blonde Indian) and Sherry Simpson (Dominion of Bears). The 2014 Crosscurrents tour will begin in Juneau, where Hayes and Simpson will team up for an onstage discussion to kick off the 2014 Evening at Egan Lecture Series at University of Alaska Southeast. Their talk, titled “Learning to Listen, Listening to Learn,” will address cultural appropriation in Alaska literature. Simpson and Hayes will continue their on-stage conversations in Craig, Sitka, and Ketchikan, and the following evening in each community they will co-teach a creative writing workshop on the craft of place-based writing, titled “The Story and the Music: Fresh Approaches to Familiar Places.”

Gwich’in Elders Traditional Stories Project University of Alaska Fairbanks • Arctic Village, Beaver, Venetie • $3,000

Underway since May 2013, the Gwich’in Elders Traditional Stories Project is an ongoing effort, initiated and led by Gwich’in Elders, to record and preserve traditional Gwich’in stories. The project also records interviews with Elders giving their reckoning of the spiritual underpinnings, cultural identifiers and moral lessons of stories that predate recorded history and express the animistic perspective that all things are a sacred gift from existence. Elders from Arctic Village, Beaver, and Venetie are currently participating, with others from the Yukon-Koyukuk region expected to join. The stories will be published in Gwich’in and English in a low-cost book to be distributed within Gwich’in communities in order to bolster a sense of cultural identity,

A L A S K A H U M A N I T I E S F O R U M S P R I N G / S U M M E R 2014

particularly with Gwich’in youth. Digital recordings and transcripts of the stories and interviews will be catalogued and archived at the University of Alaska Fairbanks. The tradition bearer for the project is Paul Williams, Sr. a traditional chief from Beaver who speaks Gwich’in as his first language. In one Elder participant’s words, “This knowledge is not intended only for our Gwich’in people, but it is for anyone who is willing to understand and learn from the Old Wisdom of the Elders.”

Courtesy Picador