3 minute read

THE BOUNDARY DISPUTE

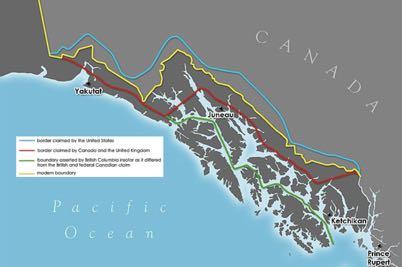

When the United States purchased Alaska from the Russian Empire in 1867, one of the best real estate deals in history was sealed, but the U.S. government also inherited a few headaches, not the least of which was a contentious disagreement over the geographic boundaries between the southeastern part of the territory of Alaska and the province of British Columbia, which had recently joined the newly formed Canadian Confederation, whose foreign affairs were still under British authority.

In 1825 the Russian Empire and Great Britain had signed The Convention Concerning the Limits of Their Respective Possessions on the Northwest Coast of America and the Navigation of the Pacific Ocean, better known as The Treaty of Saint Petersburg of 1825. Throughout the period of Russian colonization, from the 1780s to the United States’ purchase of the territory, the southeastern border of Russian America—known today as the Alaska Panhandle—was never firmly established, and when the U. S. bought Alaska the boundary terms were still ambiguous. It would take an international tribunal to resolve the dispute almost forty years later, in 1903.

Advertisement

In his review of a book by Norman Penlington, The Alaska Boundary Dispute: A Critical Reappraisal (MvGraw-Hill Ryerson Ltd., 1972), in the Summer, 1974 issue of Alaska Journal, the noted historian and University of Alaska emeritus professor Claus-M Naske wrote about the 1825 treaty and noted, “Trouble quickly arose however, over the clause which related to the boundary between Portland Canal and Mount Saint Elias. Drawn by diplomats who were entirely ignorant of the geography of the region, Russia interpreted the agreement of 1825 in an 1826 map which showed the boundary lines ten leagues distant from the coast until it reached the 141st meridian, then following that line. In 1827 Russian issued the same map in French. If Great Britain, which must have been aware of the map, differed with the Russian interpretation, it should have protested then. No disagreement was voiced, however, and it was this boundary line which the United States accepted when it purchased Alaska from Russia in 1867.”

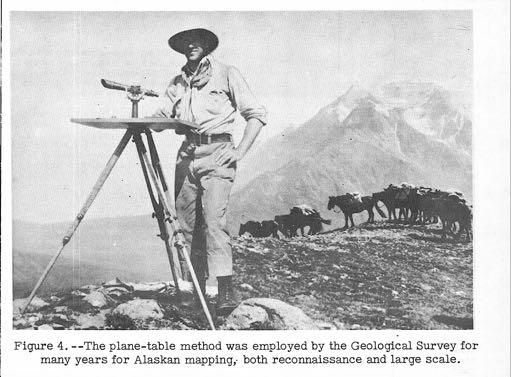

In 1871 the Canadian government requested a survey to determine the exact location of the border, but the United States rejected the idea as too costly because the border area was very remote and sparsely settled, and there was no economic or strategic interest in conducting a survey there. That was challenged with the Cassiar gold rush in 1862 and the Klondike gold strike in 1897 intensified the pressure to survey the border.

The desolate summits of Chilkoot Pass and White Pass, both at the head of Lynn Canal, comprised the main gateway to the Yukon, and when thousands of gold-seekers began pouring into the country the North-West Mounted Police sent a detachment to secure the border for Canada at those points. This was still disputed territory, as many Americans believed that the head of Lake Bennett, another 12 miles north, should be the location of the border. The Canadian government also sent the Yukon Field Force, a 200-man Army unit, to set up camp at Fort Selkirk, at the confluence of the Pelly and Yukon rivers, so they could be dispatched to deal with potential problems at the passes or on the 141st meridian west.

The provisional boundary set up by the North-West Mounted Police was accepted, but a more permanent deliniation was needed for the long term. A joint commission attempted to resolve the dispute in 1898–99 and failed. In 1903 the problem was referred to an international tribunal, whose members included three American politicians (Elihu Root, Henry Cabot Lodge and George Turner), two Canadians (Sir Allen Bristol Aylesworth and Sir LouisAmable Jetté) and Lord Alverstone, Lord Chief Justice of England.

The Canadian and American representatives favoured their respective governments’ territorial claims, and, to the dismay of the Canadians, Alverstone supported the American claim. The Canadians, outraged by what they saw as a betrayal by their colonial government, refused to sign the final decision, but the question had been put to binding arbitration, the decision took effect, and the resolution was issued on October 20, 1903. The boundary was considered a reasonable compromise, roughly approximating the Russian line on the map which had been unchallenged for almost 60 years. ~•~