16 minute read

ALEXANDER HUNTER MURRAY

Alexander Hunter Murray and The Hudson’s Bay Company at Fort Yukon • 1847-48

Near the Confluence of the Porcupine and Yukon Rivers North America, with its vast forests and wildlife, led to the continent becoming a major supplier of fur pelts for the garment trades of Europe, where fur was relied on to make warm clothing, a critical consideration prior to the organization of coal distribution for heating. The Hudson’s Bay Company was a British trading firm, incorporated in England in 1670, and the oldest commercial corporation in North America. In 1821 the company merged with its main competitor, the North West Company, established in 1779, combining 97 trading posts of the North West Company with 76 from the Hudson's Bay Company. Maintaining the Hudson’s Bay name, the company dominated early trading in the United States and Canada, especially the fur trade.

Advertisement

On the 25th of June, 1847, Chief Trader and artist Alexander Hunter Murray of the Hudson's Bay Company established a fur trading post and stockaded fort in northeastern Russian America, just upstream from where the Porcupine River empties into the mighty Yukon, at a point slightly north of the Arctic Circle. Named Fort Yukon, Murray’s trading post would become one of the most valued by the Company, reaping the rich harvest of furbearing animals indigenous to the Alaskan interior, and the town which formed around the logistically well-placed post would play an important role in the history of Alaska.

Alexander Hunter Murray was born at Kilmun, Argyllshire, Scotland in 1818, the son of Commodore Murray, R.N., of a famous firm of publishers in Glasgow which produced the Murray Railroad Guide. Alexander was described as “a clever man, of no ordinary talent and ability, an artist, engineer and surveyor, and in fact was an adept at almost anything he turned his attention to, and was withal a most genial companion, well-informed on any subject and had such a pleasing conversational power that it was no ordinary treat to spend a night at home with him.”

Murray emigrated to the United States as a young man and found work with the American Fur Company, founded in 1808 by John Jacob Astor, one of the largest enterprises in the young nation, with a near-monopoly of the fur trade. Through his profits from the company Astor made lucrative land investments, becoming the first multi-millionaire in the United States and the richest man in the world.

According to his biographical sketch at the online Dictionary of Canadian Biography, “No fur-trader ranged farther over North America than Alexander Hunter Murray. According to his Journal of 1847–48 he had early been in the swamps of Lake Pontchartrain (near New Orleans, La.) and along the Red River in Texas. It is difficult to determine exactly how or when he got there and nothing much is known about his life until he became an employee of the American Fur Company working out of St Louis, Mo. In 1844–45 he was on the upper Missouri River and there he sketched the fur posts of that region: forts Union, Pierre, Mortimer, and George.”

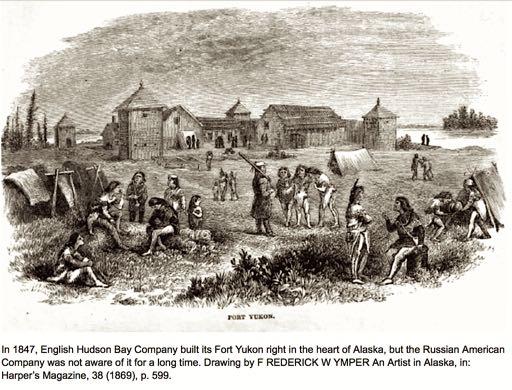

Fort Yukon; Hudson's Bay Company's Post, 1868 Illus. in: Frederick Whymper, Travel and Adventure in the Territory of Alaska, London, 1868

Alexander Hunter Murray

An article in the June, 1929 issue of The Beaver, the magazine of the Hudson’s Bay Company, notes “About 1845 he came up from Missouri to Fort Garry and entered the service of the Hudson’s Bay Company.” He was appointed senior clerk due to his extensive experience and transferred to the Mackenzie River District under the Chief Factor Murdoch McPherson. En route to his new post Murray met and married the daughter of Chief Trader Colin Campbell of the Athabasca District. They were married at Fort Simpson by McPherson, the marriage was registered at the Red River Settlement, in the future Manitoba, on August 24, 1846, and the couple traveled to Fort McPherson, Northwest Territories, to spend the winter. The first Hudson's Bay Company trading post north of the Arctic Circle, Fort McPherson was the principal post in the Mackenzie Delta region.

In the spring of 1847, Murray traveled over the Richardson Mountains with his wife Anne, and while she remained at the newly-established Lapierre House on the Bell River, he, with a small company of men, launched their small boat, Pioneer, and descended the Bell (Rat) River to the Porcupine, and continued down the Porcupine to the Yukon. A detailed narrative of the post’s construction and first year was kept for Murdoch McPherson, Chief Factor at Fort Simpson; it was printed as Journal of the Yukon in 1910. In his journal Murray wrote very meticulous records of every bend and bank in the rivers with sometimes lengthy compass readings, and included local sights of interest, weather reports, and details of their interactions with the native people they met along the way.

Finally arriving at the mouth of the Porcupine, they “….entered the turbid waters of the Youcon,” and with the help of the local Indians found a suitable place to make camp.

Chief Saveeah, or ‘Rays of the Sun’

Murray’s first impression was not favorable. “I must say, as I sat smoking my pipe and my face besmeared with tobacco juice to keep at bay the d——d mosquitos still hovering in clouds around me, that my first impressions of the Youcon were anything but favourable. As far as we had come (2 1/4 miles) I never saw an uglier river, every where low banks, apparently lately overflowed, with lakes and swamps behind, the trees too small for building, the water abominably dirty and the current furious; but I was consoled with the hopes held out by our Indian informant, that a short distance further on was higher land.”

The next morning Murray set out with his Indian guides, “who seemed to take great interest and pride in showing us the best places, and in describing the banks of the river above and below.” Finally settling on a dry ridge about 300 yards long and 90 wide, Murray and his men set about constructing a post, which would have three large log buildings for the traders, surrounded by a one hundred foot square log stockade, with a fortified blockhouse at each corner of the stockade, comprising a classic western-style fort which would be, according to Murray’s journal, “the best and strongest between Red River and the Polar Sea.”

Murray wanted the fort strong because he knew he was within Russian territory, as explained in an article by Martha Munger Black, F.R.G.S., wife of the Hon. George Black, K.C., Speaker of the Canadian House of Commons, in an article for the Hudson’s Bay magazine, The Beaver, June, 1934. Quoting from Murray’s 1847 journal, she wrote of his journey to the future site of the fort, and noted, “It was now that he began to glean specific news of his dreaded rivals, the Russians. A party of Indians came in who had had some dealings with the Russians, and they described how these were all well armed with pistols and were abundantly supplied with ‘beads, kettles, guns, powder, knives and pipes and traded all the furs from the bands, principally for beads and knives, after which they traded dogs, but the Indians were unwilling to part with their dogs, and the Russians rather than go without gave a gun for each, as they required many to bring their goods across the portage to the river.’”

Murray wrote in his Journal: “This was not agreeable news to me, knowing that we were on their land, but I kept my thoughts to myself, and determined to keep a sharp lookout in case of surprise. I found that the population of this country was much larger than I expected, and more furs to be traded than I had goods to pay for.”

Having taken the measure of the land, Alexander Murray “determined to build a fort worthy of it.” Martha Black continues, “It was also to be worthy of the possible foes, both white and red, who surrounded him. So the stores and dwellings were made of solid timbers, the pickets walling them in were not mere ‘pointed poles or slabs, but good-sized trees dispossessed of their bark and squared on two sides to fit closely and fourteen and a half feet in height above ground, three feet underground. The bastions will be made as strong as possible, roomy and convenient. When all of this is done the Russians may advance when they damn please,’ he declares.”

In another issue of The Beaver, Winter 1959, Canadian writer Ethel Stewart described a remarkable scene: “On 28 June 1847, three days after his arrival at the junction of the Porcupine with the Yukon River, a site on which he proposed to build Fort Yukon, Alexander Hunter Murray heard a salute of gunfire from the river. Lest silence be mistaken for hostility, he quickly ordered his men to return the salute. The party, consisting of eighteen persons, landed, and forming a chain, with the chief and his men in front and the women and children to the rear, danced forward by degrees until they were in front of the white man’s camp. A party of Kutchin, already present, joined them to form a large circle with the chiefs in the centre and danced before the visitors for half an hour without ceasing. Thus the young chief introduced himself to the men of the Hudson’s Bay Company.”

"Dance of the Kutcha-Kutchin,” from a drawing by Alexander Hunter Murray, 1848. Designed by Georges Beaupré for the Canadian Postal Service, 1975. Murray’s original sketch from his Journal is above. The unsual stance of the central dancer shows influence of the Cossack-style dance lnown as Hopak, a Ukranian folk dance likely learned from the Russian traders.

The ‘young chief’ mentioned by Stewart was called Saveeah, or Rays of the Sun, “a fine looking young man, easily distingished from his companions by the three eagle feathers he wore at the back of his head, and by the profusion of beads and shells on his tunic and trousers. Though these were the first white men the Yukon Indians had seen, they had already received guns and beads through indirect trade with the Russians.”

Alexander Hunter Murray commented on Saveeah’s hunting skills in his journal, noting that the chief brought in more furs and meat than anyone, indicating the leadership which secured the chief’s influence and reputation. Known later in life as Sah-neu-ti, he would be sketched by F. J. Whymper and described by William H. Dall in his book, Alaska and its Resources, in 1870. As late as 1888 the chief was described by the McConnell survey party as the most powerful chief in the Yukon country. He died in 1900 and was buried in the churchyard at Fort Yukon, “the last Kutchin chief to exercise real power over his people.”

An 1871 report to the U. S. Senate includes Captain Chas. W. Raymond’s Reconnaissance of the Yukon River in Alaska Territory, July to September, 1869, the main object of which was the determination of the latitude and longitude of Fort Yukon. Capt. Raymond was very favorably impressed by the native people of the Fort Yukon area, writing in his report: “A few trading parties came to the station during our visit, and among them were the finest Indians that I have ever seen. The women are virtuous; the men are brave, manly, intelligent, and enterprising. They are said to be essentially a commercial people, trading for furs with other tribes and disposing of them again to the white traders. Some of them were very much interested in my operations, and I found no difficulty in making them comprehend, through an interpreter, the general method and purpose of my astronomical observations. Indeed, they are accustomed to note time roughly by the relative positions of stars. Their clothing is of mooseskin, with the exception of a few articles which they obtain by trade. They fish little, and are almost exclusively engaged in trading furs and hunting the moose which abounds in these parts.”

Engraving of two Gwich'in hunters based on a sketch in Alexander Hunter Murray’s journal, written in 1848, published in 1851. The nose ornaments were highly prized dentalium shells, obtained in trading—directly or indirectly—with coastal tribes. Original sketch from Murray’s Journal, labeled ‘Kootchin hunters,’ above, with front, side, and rear views of the hunters and their garb.

Some excerpts from Alexander Hunter Murray’s Journal of the Yukon 1847-48, which was published in 1910 by the Canadian Government Printing Office in Ottawa, and is available to read or download online:

June 29th. Little work was done by the men yesterday except grinding and handling their axes. Today we erected a temporary store for the goods and provisions and a scaffold for drying meat. One of the men was employed preparing a small piece of ground for an experimental garden. The day was showery and warm, and our fresh meat, now more than we could use, beginning to spoil, several of the Indian women were employed in cutting it up, for which they each received an awl, and considered it great payment. I had some more talk with the Indians, a few of them left to kill a moose for us, the others remaining and although inquisitive and often in our way, were becoming in their manners, and offering to assist in whatever had to be done. ….Our encampment was a pleasant place, quite a little village entertaining no less than six dwelling houses, all built upon the Sabbath day, for which I am not to be held accountable. They were made of willow poles covered with pine bark, and fashioned according to the fancy of their owners, some open at the end, some half open, and some with only a small door. Besides these six houses, there was a log store, also another cabin for containing dried fish, two more scaffolds, and a garden measuring 12 feet by 8—said garden was prepared and fenced out, and on the 1st of July a few potatoes were planted, and it was my peculiar care and pleasure to attend to it and have it duly watered in droughty weather, never expecting, that at that advanced season the crop could be brought to maturity, but to try by every means in my power to preserve seed for the ensuing summer.

Except a few sticks, all the building wood had to be brought in the boat from the islands opposite about 3/4 of a mile distant, but owing to the numerous battures and the strong current in the river, they had to go about two miles to reach the islands, and more time was occupied in going and coming than in cutting and squaring the wood.

We were seldom without visitors, and they did not often come empty-handed, we always had plenty to eat and plenty to do so that none were allowed to weary. Geese and duck were always passing, and now and then a Beaver would clap his tail ‘en passant’ before our levee. The woods behind abounded in rabbits and partridges, and go which way one would, if a good shot, he need not return without something for the kettle.

We lived on good terms with the natives and feared nothing, except to see two boat loads of Russians heave round the point….

Alexander Hunter Murray left Fort Yukon with the returns of the first season in June, 1848, rejoining his wife who had remained at Lapierre House, on the Yukon side of the border. His journal ends there, and in his final entry directed at Murdoch McPherson, Chief Factor at Fort Simpson, he advises providing more trade goods in future seasons:

I know myself of upwards of twenty men who have furs for a gun each on my return. I could dispose of any quantity of guns this summer, and I do hope you will send as many as possible, the Indians all prefer our guns to those of the Russians. Guns and beads, beads and guns is all the cry in our country. Please to excuse me for repeating this so often, but I cannot be too importunate, the rise or fall of our establishment on the Youcon depends principally on the supply of these articles.

Illustrations from Murray’s Journal.

Chief Trader A. H. Murray and his wife, Anne.

Murray also comments on the potentially problematic Russians: I had some more conversation with the Indians that arrived before we left, respecting the Russians, from what they all say it is my firm belief that we shall see the Russians this summer, they have been making every preparation on the portage to descend the river. The more I think on this subject I am at the greater loss how I shall act, but hope to receive full instructions from you. They may order us to leave the coumtry, perhaps try to force us from it should we persist in remaining, and I should be very sorry to involve the Company in any difficulty with our Russian neighbours. But I only received orders to establish a post in the Youcon, which is done, nothing was said concerning the Russians trade or territory, and it is my private determination to keep good our footing until decisive instructions are received.

Alexander Murray and his wife returned to Fort Yukon later in 1848, where they remained until 1851. An excerpt from the Introduction relates: In 1850 he accompanied Robert Campbell to Lapierre House; and the following year finally left Fort Yukon, returning to Fort Simpson on the Mackenzie, where he spent the winter. In the autumn of 1852 he reached Fort Garry with his wife, and several children, who had been born to them in the north country. Murray spent the succeeding winter at Fort Pembina (now Emerson), of which he had charge for the Hudson's Bay Company, for several years, after which he was appointed to the management of the district of Lac la Pluie, or Rainy Lake, and Swan River. Returning to Pembina, he was promoted to a Chief Tradership in 1856.

In 1857, in poor health, Murray traveled to Scotland, where he visited his old home. His travels restored his health, and he was put in charge of Fort Alexander for a time, and then in 1862 he was given charge of Lower Fort Garry, where he spent several seasons. He retired from the service of the company in 1867, spending his remaining years at his home on the banks of the Red River. He died at the age of 56 in 1874, survived by his wife Anne, three sons, and five daughters.

In a life filled with travel and adventure, Alexander Hunter Murray considered the construction of Fort Yukon his greatest achievement. An acquaintance was quoted in the Introduction to his Journal, saying of Murray: “His own experience in Rupert's Land had been great and long continued—but the adventure on which he most prided himself, evidently, was his having founded the most remote post of the company, Fort Youcon, in Russian America, situated within one or two degrees of the Arctic circle.”

When Alaska was purchased from Russia by the United States in 1867, the precise location of Fort Yukon was still unknown. An American reconnaissance expedition established the latitude and longitude in 1869, and the fort was dual occupied during the winter of 1869-1870 by the Hudson’s Bay Company and the American company which would take over the post.

In November, 1869 the Hudson’s Bay Company sent five men to construct the first Rampart House as a replacement, just over the border on the ramparts of the Porcupine River, and the post was relocated in the spring of 1870. Rampart House was later moved twelve miles farther upstream to ensure its being well within British territory, and according to a 1969 article in The Beaver, “was kept up mainly as a protection against the encroachments of American traders from Alaska.”

A report by R. G. McConnell of the Geological Survey of Canada noted that by 1887-88 Fort Yukon had been entirely abandoned, and its timbers cut up to supply wood for the steamboats plying the Yukon River. ~•~