6 minute read

From Open-heart to Open Season

One Hunter’s Journey to Recovery

► article and photos by Joshua P. Martin

“Are you feeling all right?”

“Yeah, I feel great.”

The room fell silent and neither of us spoke. I had been through enough ultrasounds to know the technicians only ask you that question when they see something they don’t like, and you probably won’t either. I didn’t need the results to know what came next—the aortic valve they put in eight years earlier needed to be replaced.

Over the following days, I processed my feelings and the implications of another open-heart surgery. I was flooded with emotion and thoughts typical of someone facing their mortality head-on—like how I was too young to die—and worrying about my wife and young girls. Once I was done feeling sorry for myself, and rationalized the relative risk, I quickly realized what was really at stake—hunting season!

Recovering from open-heart surgery is no easy task. Anyone who has been through one knows it can take up to a year to feel “normal.” I didn’t have a year though. I would have two months to get back in hunting-ready condition for the opener. As a primarily public land hunter, finding game for me is physical. When my last season ended with no meat to show for countless days away from home, I assured my wife I would do better next time around and was training and shooting my bow regularly in the off-season. I had also been listening to podcasts, reading books, and looking for all the tips and tricks possible to give me an edge. The damaged valve was putting all that hard work at risk.

A month-and-a-half later, I woke up from my second valve replacement in less than a decade. In the days and weeks that followed, I lost weight, struggled to breathe, and was physically weak. Once I got through the worst of it and other priorities were getting attention, like spending time with my family, I started to train again. One of the first things I did was reduce the draw weight of my bow as much as it would allow, to about 48 pounds. I then took my first shot in months. Hearing the crack of the bowstring was instantly therapeutic and, to my surprise, I felt no pain. It was now early July, and I was finally healed.

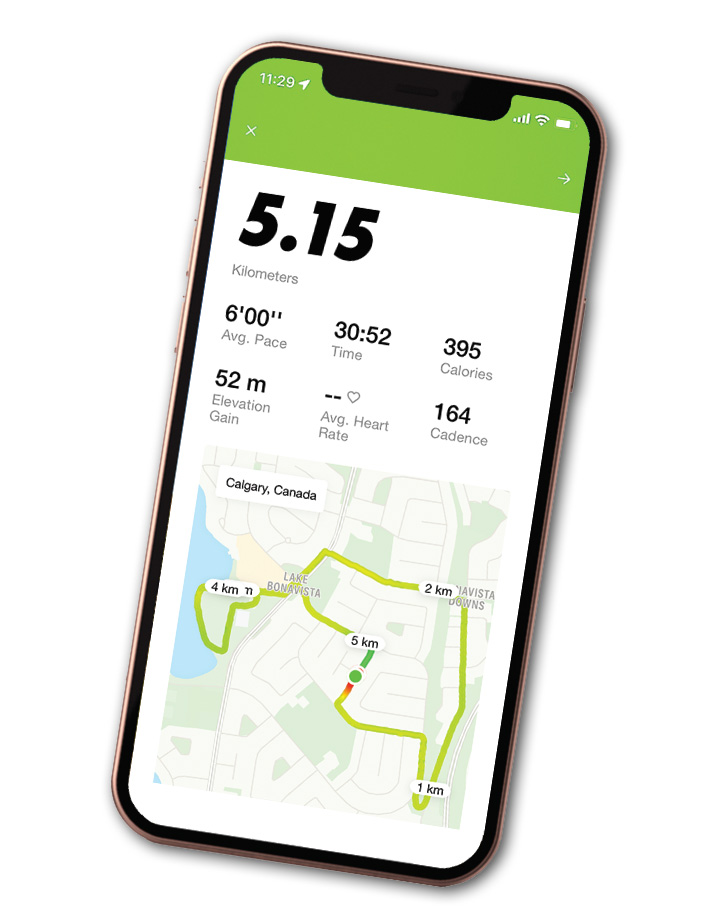

From then on, the plan was simple— shoot ten arrows and exercise 30 minutes daily until the opener. It didn’t matter whether the 30 minutes was filled with running, rowing, weights, or hiking, so long as it was physical. On my first run, if you can call it that, it took me 18 minutes to do the 1.4 kilometre block around my house, a pace of 13 minutes per kilometre. I finished the workout with some calisthenics and was absolutely destroyed. Two months later I was running five kilometres on a six-minute pace and back to my draw weight of 70 pounds. On the opener, I hiked 11 kilometres with a full pack, and was in the best shape of my life.

Gratitude is a powerful motivator and that season I hunted harder than I ever had before. When I loaded up my tent trailer for one last weekend of hunting, I had already spent well over 20 days stalking through grazing leases, conservation sites, and the backcountry. All I needed was my hard work and preparation to meet up with Lady Luck.

As I left the truck on my last hunt, the weather and wind were perfect, and I felt good about my chances. Minutes later, I spotted a mule deer buck in the distance. I quickly scanned the area and figured, based on his direction of travel and pace, I could go unseen and cut him off on the other side of a small rise between us to get a shot. Once in position, I relocated him slowly grazing his way towards me. As he turned broadside, I drew my bow back, anchored, and lined up my 20-yard pin with his vitals. Then I hesitated.

As he came into focus through my peep, I immediately noticed how prominent his scapula and ribs were. Thoughts of chronic wasting disease (CWD), especially common in southeast Alberta, or some other ailment raced through my mind. I slowly let off my draw, stood up, traded my bow for my phone and, as he glanced over at me indifferently, snapped a few photos. It was likely my last chance for a successful harvest and he would be the first buck I ever passed on, so I wanted the photos to look back on when I second-guessed the decision. After spending a few minutes together in silence, he took one last bite, bounced off and disappeared into a coulee.

The rest of that day was more of the same—a few close calls and an unfilled tag in my pocket. After everything I had overcome, success still eluded me. Or did it? I spent the long drive home from that hunting trip replaying the season in my mind—the mistakes, missed opportunities, and that sickly-looking buck. While non-hunters primarily associate hunting with death and “grip and grins,” any hunter will tell you their smile is a reflection of the experience and everything leading up to the shot, not the kill itself. Considering where I started only a few months prior, perhaps it was a successful season after all.

To this day, I find myself pulling up the picture of that buck, reliving the moment and wishing I had released my arrow. However, more often than not, I’m content with the decision and thankful for the journey that brought us together in that field. I like to think that, like me, he recovered from whatever was ailing him and he’s still roaming the coulees each fall. Our paths might even cross again, though for his sake, it would be best they don’t. My health and marriage will not survive another season that ends with an empty freezer.