GATHERINGS SPOTLIGHT

SPECIAL EDITION 2025

THE ORAL HISTORY OF GLADYS BAILIN

GATHERINGS SPOTLIGHT

SPECIAL EDITION 2025

THE ORAL HISTORY OF GLADYS BAILIN

By Dr. Tresa Randall

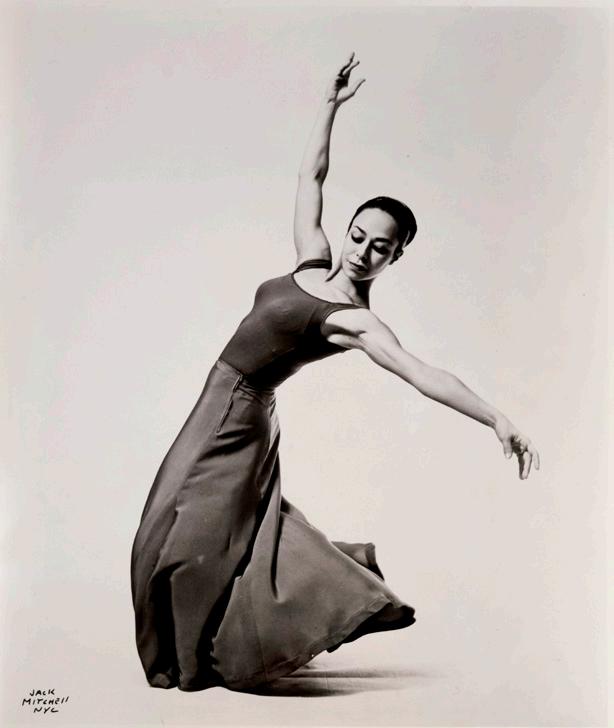

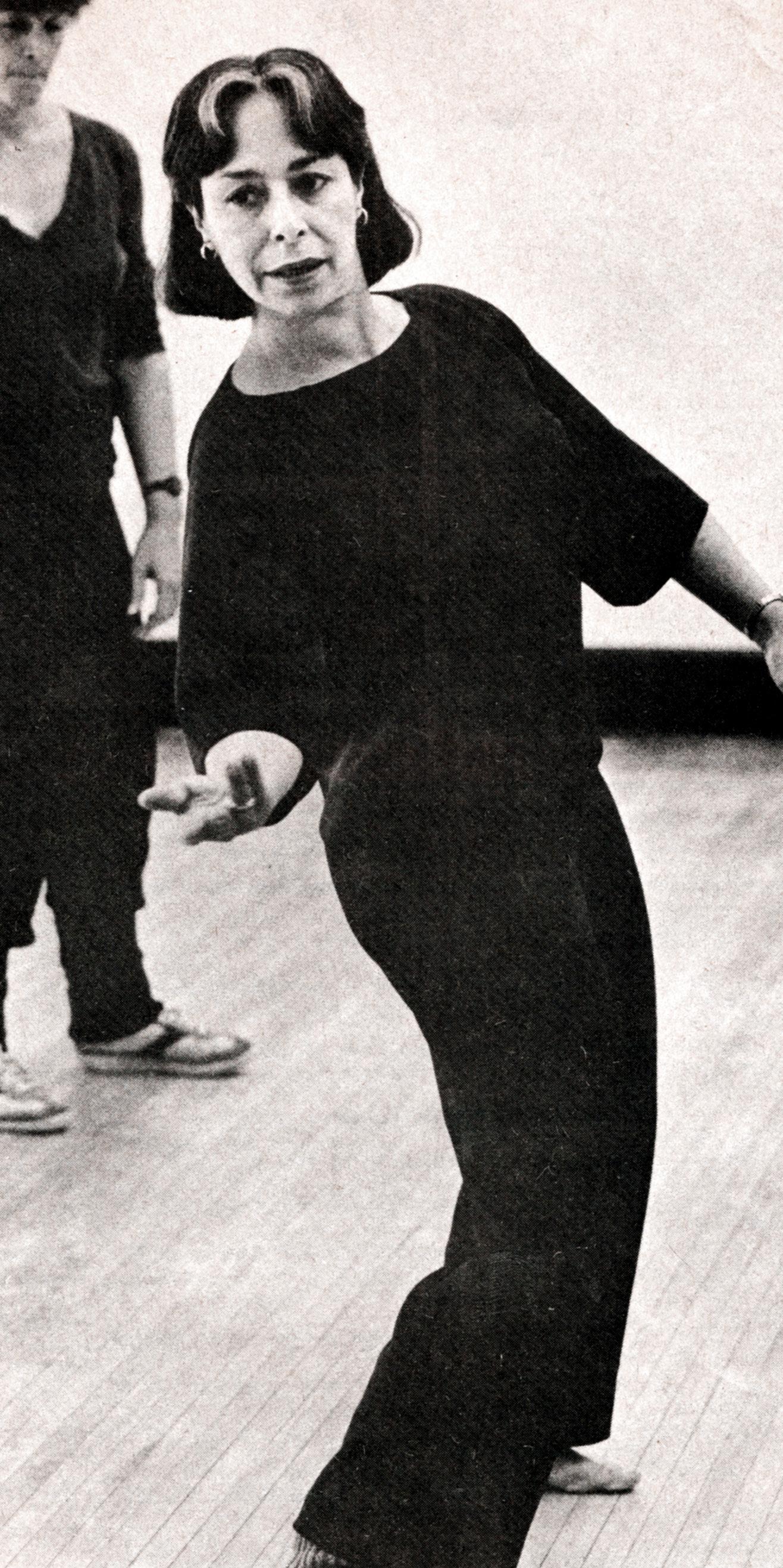

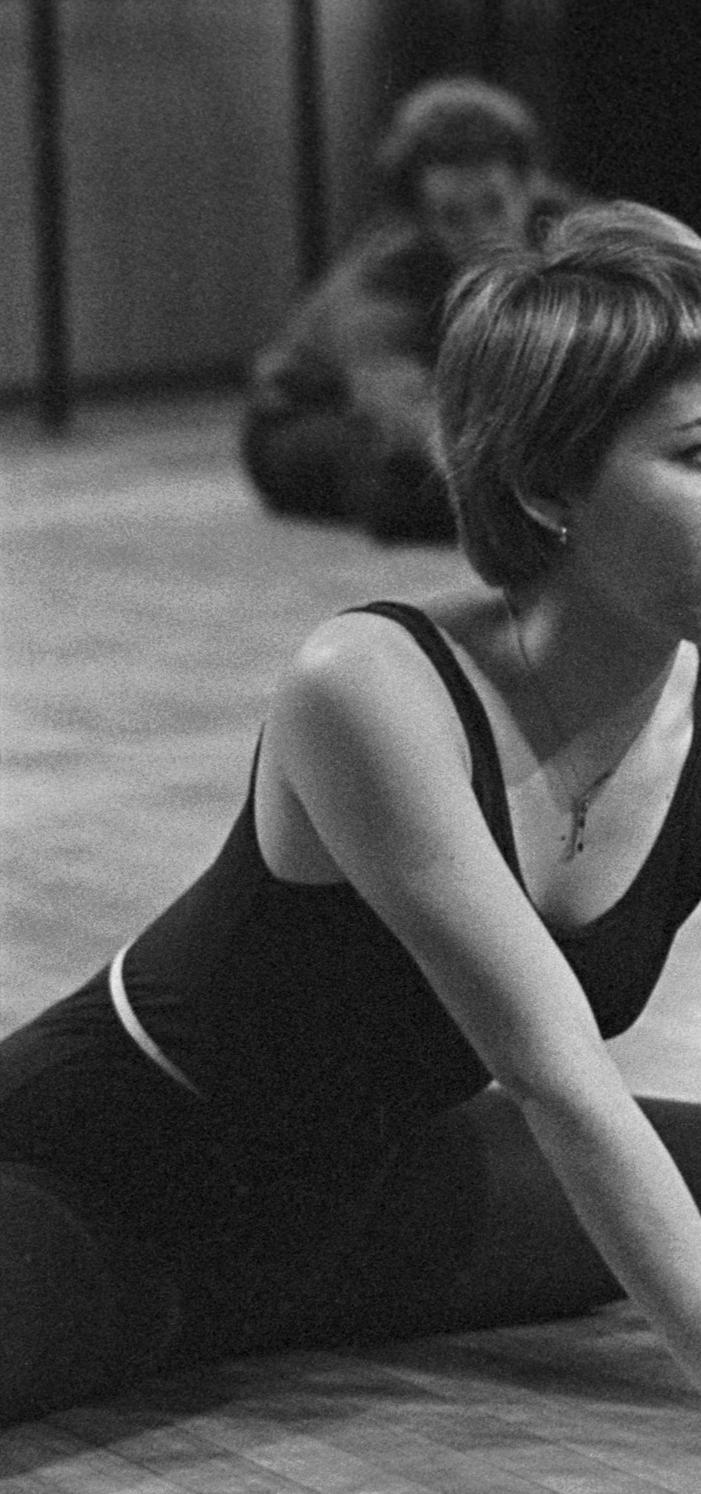

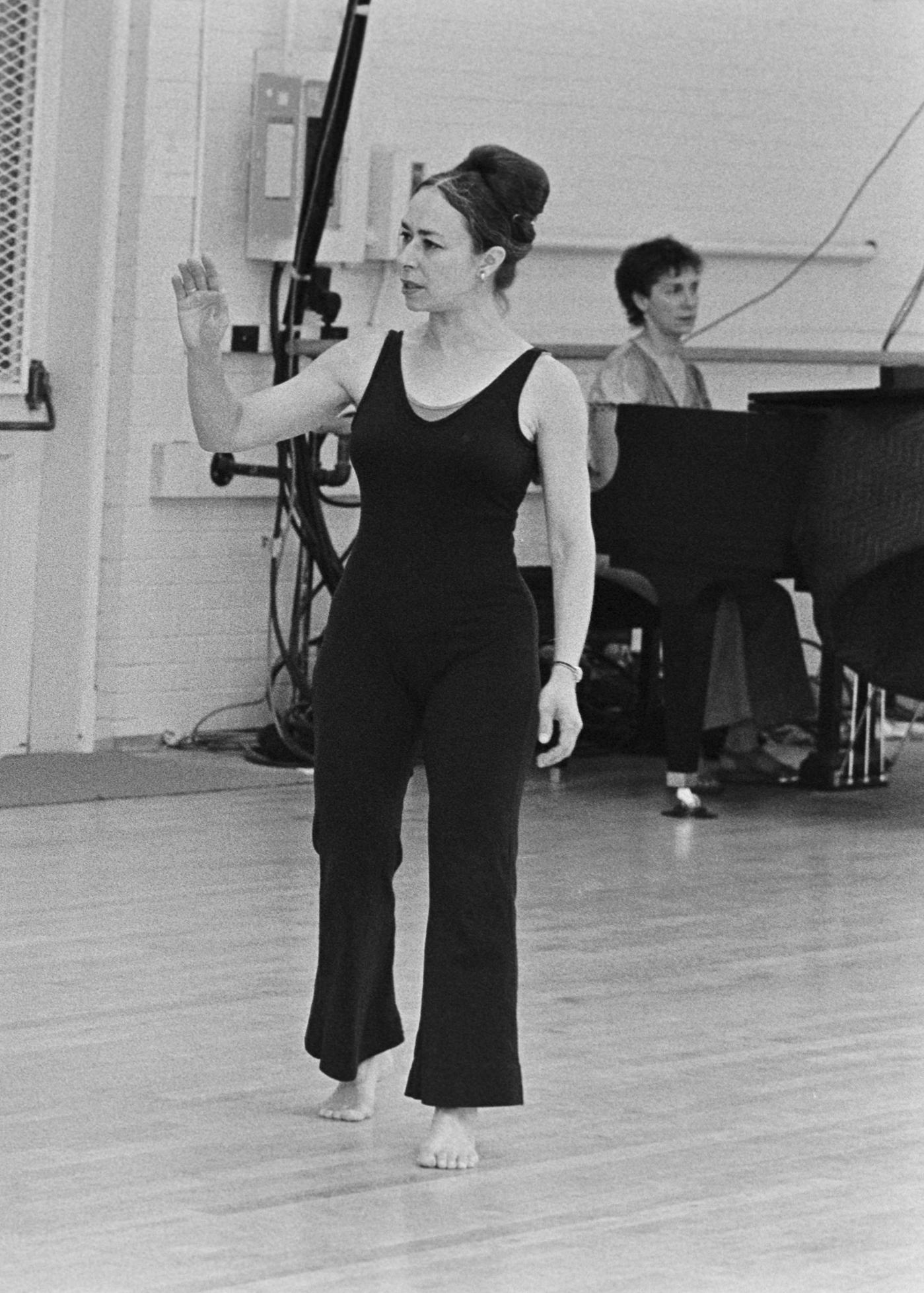

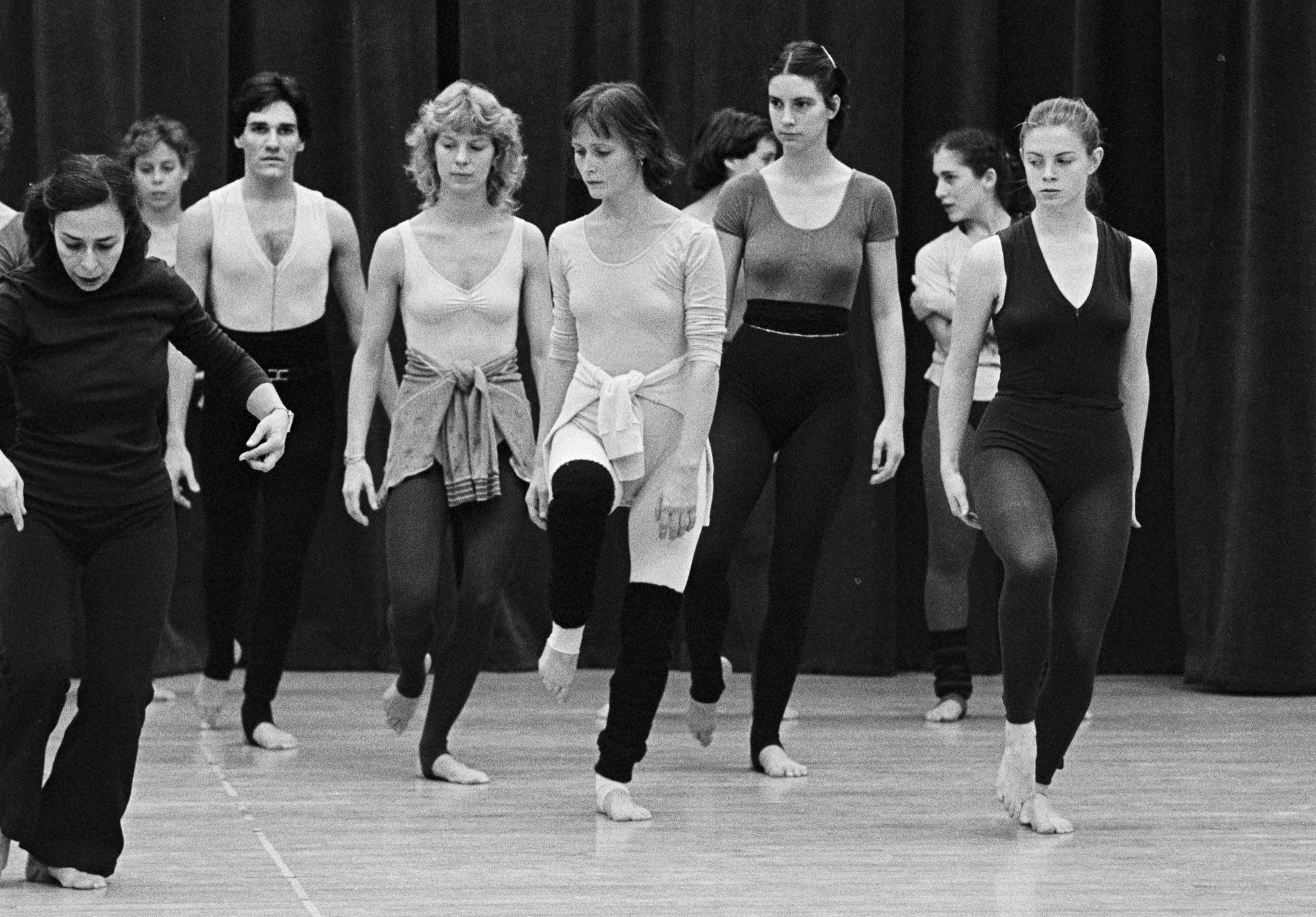

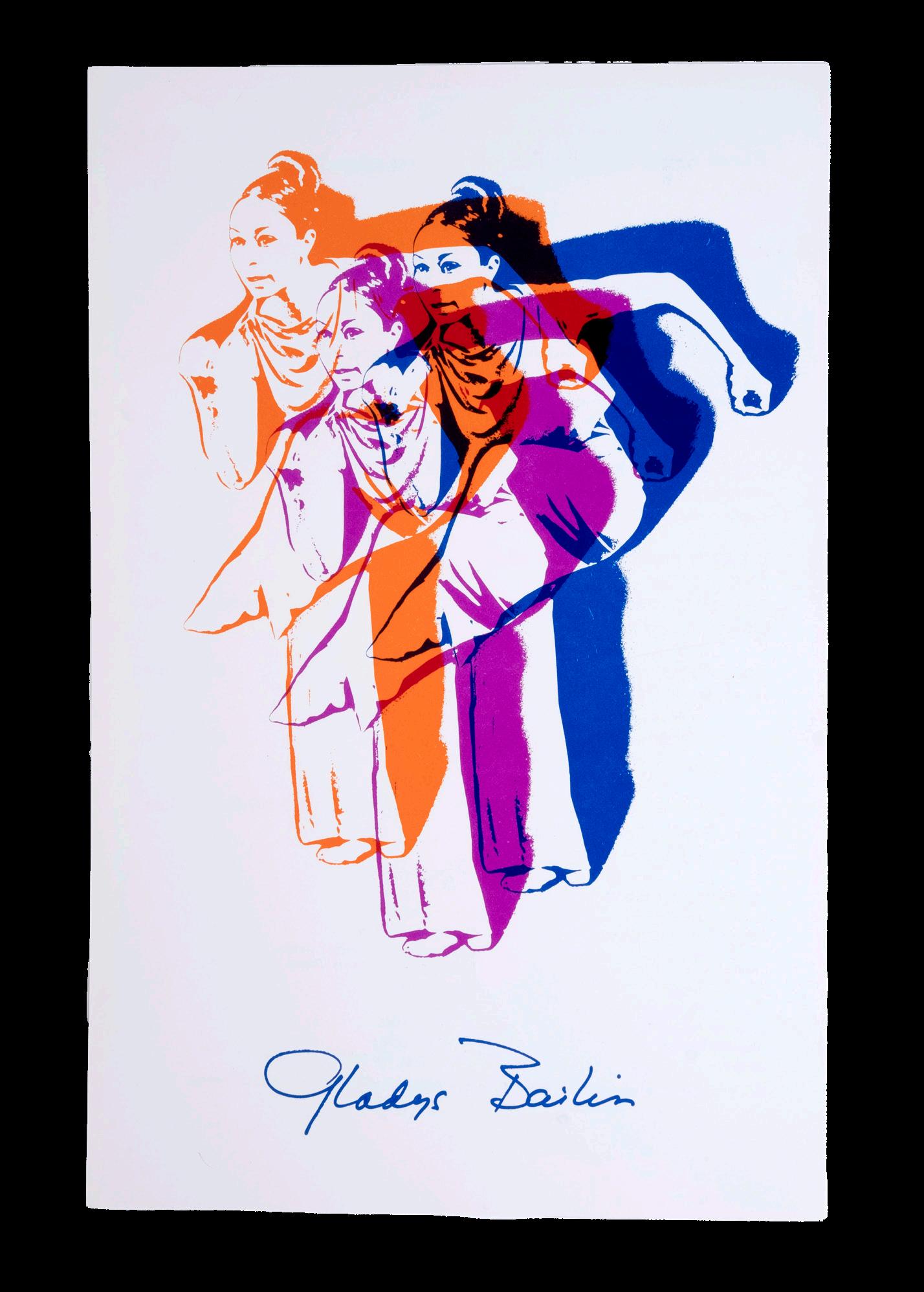

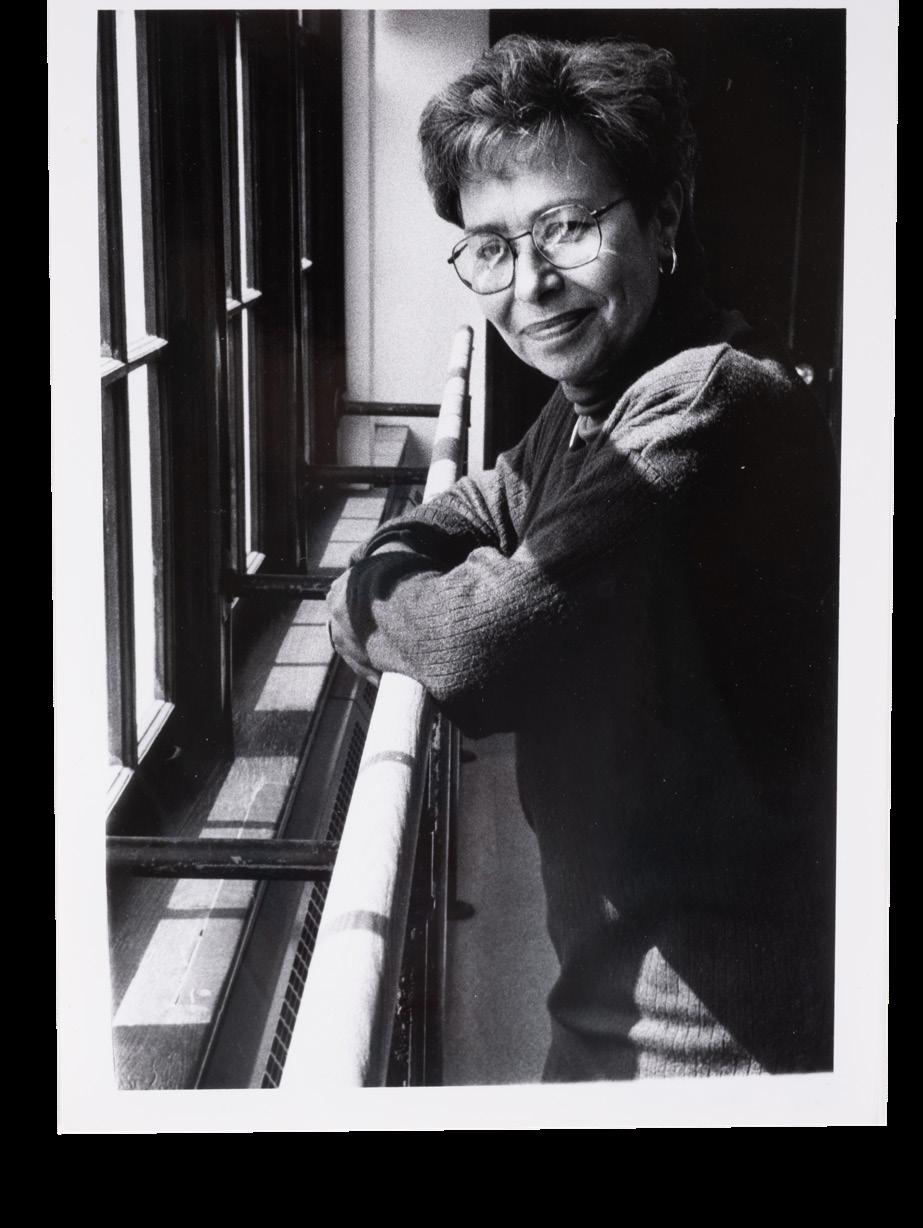

A tireless champion of dance as an art form, Gladys Bailin Stern has inspired generations of dancers with her keen wit, amiable humor and discerning eye. In her endeavors as a performer, choreographer, teacher, administrator and mentor, she is perennially creative, rigorous and energetic. In these interviews, Bailin reflects on her early training in New York City with dance legend Alwin Nikolais, her international career as a performer and choreographer, and her impact on the School of Dance at Ohio University.

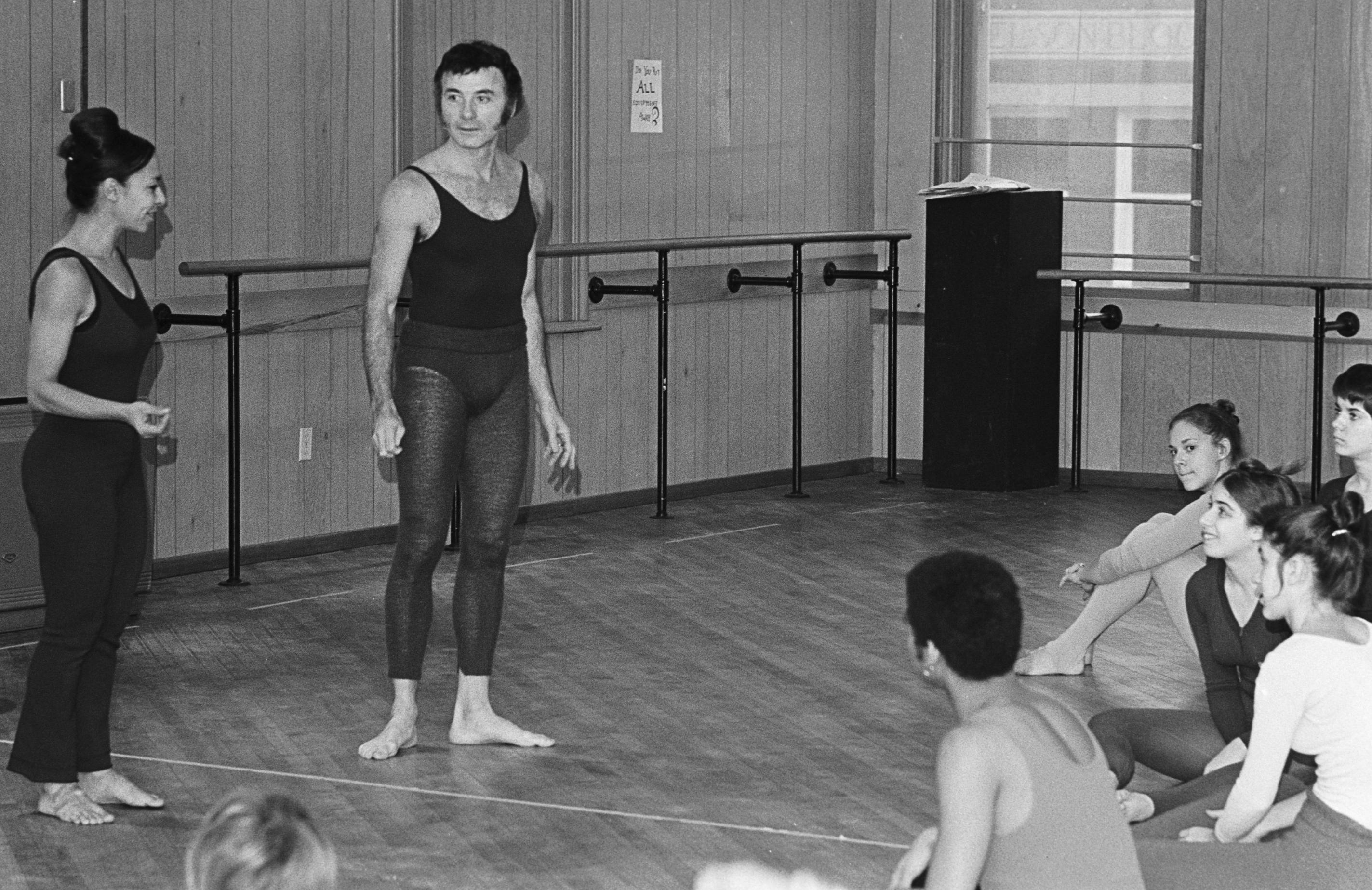

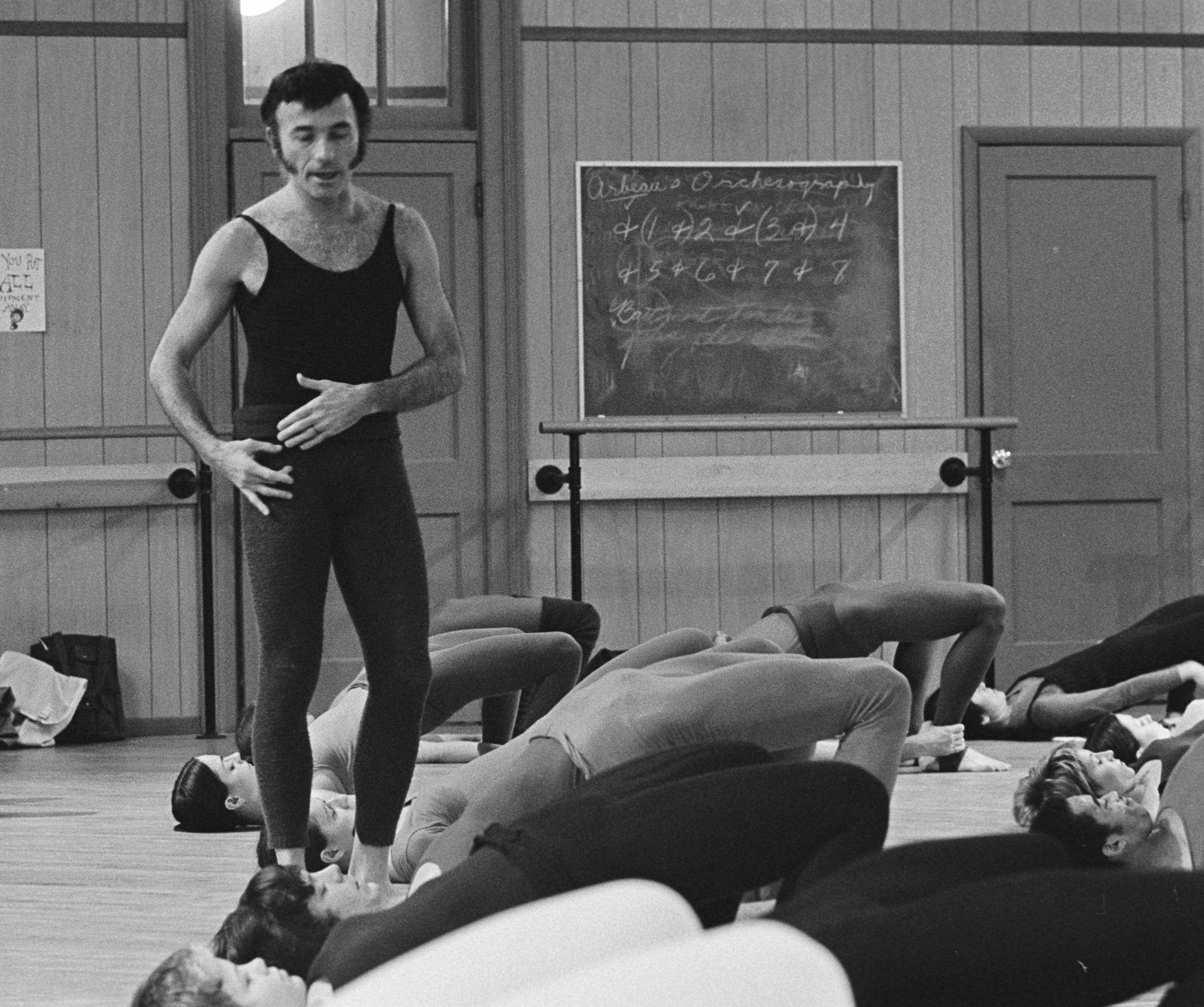

As Bailin recounts, when she studied with Nikolais at the Henry Street Playhouse in the late 1940s and early 1950s, he was experimenting with a new form of dance modernism, which emphasized abstract movement concepts and gave movement, sound and light equal importance on the stage. Under Nikolais’ tutelage, a group of young dancers that included Murray Louis, Phyllis Lamut, Bill Frank and Bailin, developed a highly articulate, dynamic way of moving that distinguished them in the modern dance field.

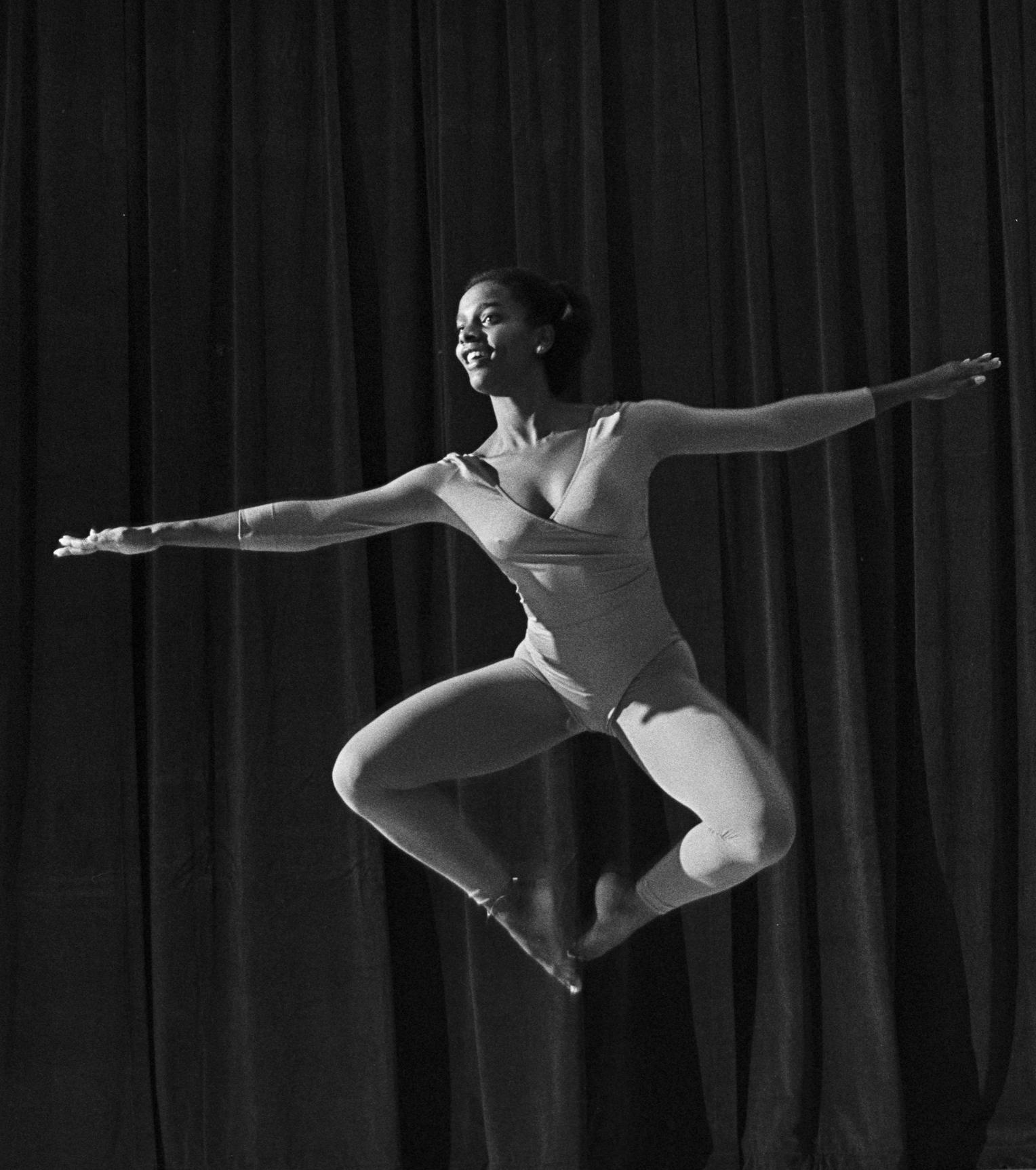

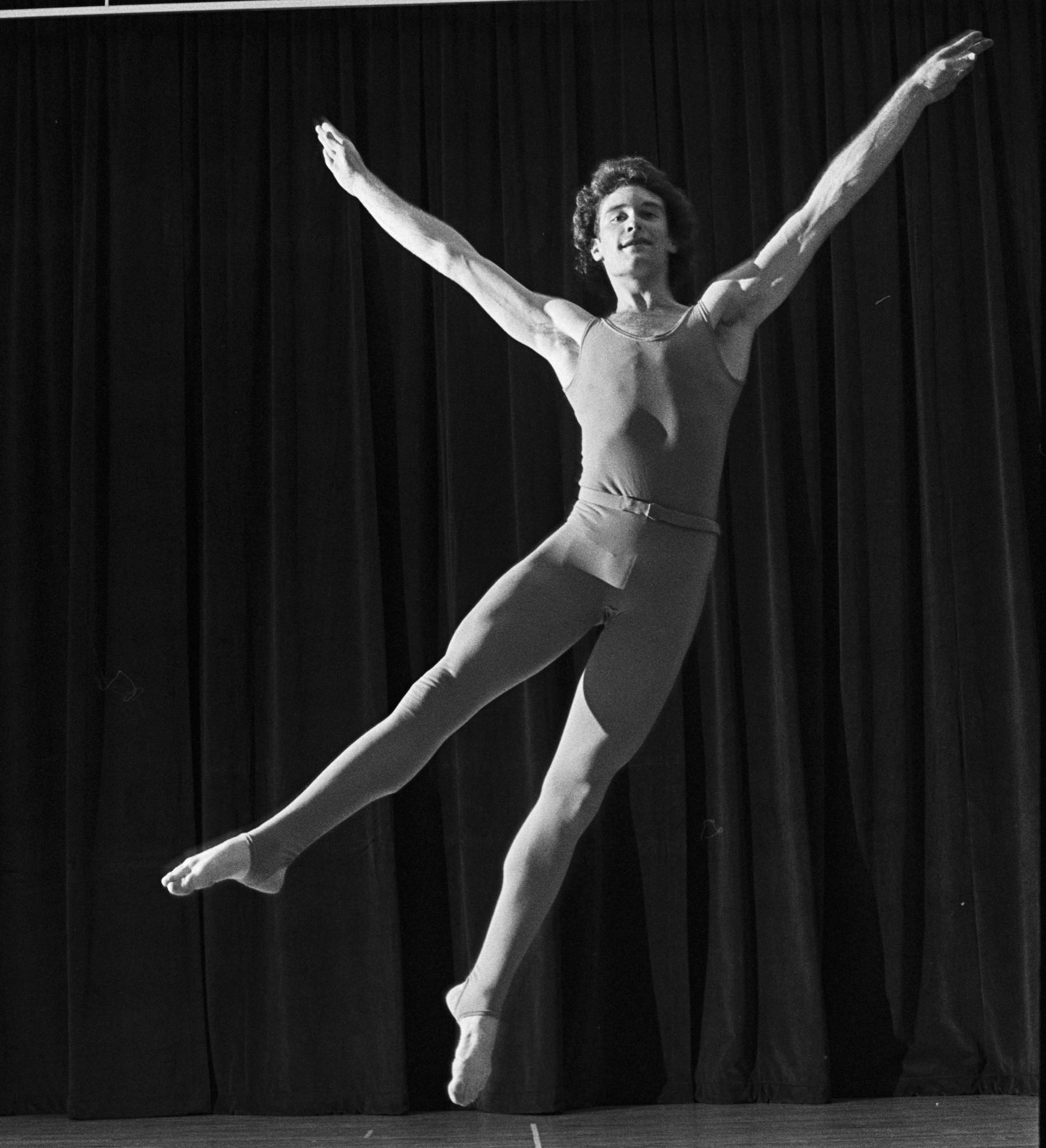

Even among a brilliant group of young dancers who brought Nikolais’ new ideas to life, Bailin stood out with her musicality and her impeccable sense of motion. She lent her own movement ideas to Nikolais’ creative process, originating roles in all of Nikolais’ groundbreaking works of this period. Bailin was in Nikolais’ company for their historic debut performance at the American Dance Festival, when dance critics declared that modern dance was entering a new era, and Bailin was one of the leading dancers as the company began to tour the world.

For more than 20 years, she performed professionally with the Alwin Nikolais Dance Company, Murray Louis Dance Company, Don Redlich

Dance Company and as a freelance soloist, touring nationally and internationally, performing on television, and appearing in the most respected dance festivals.

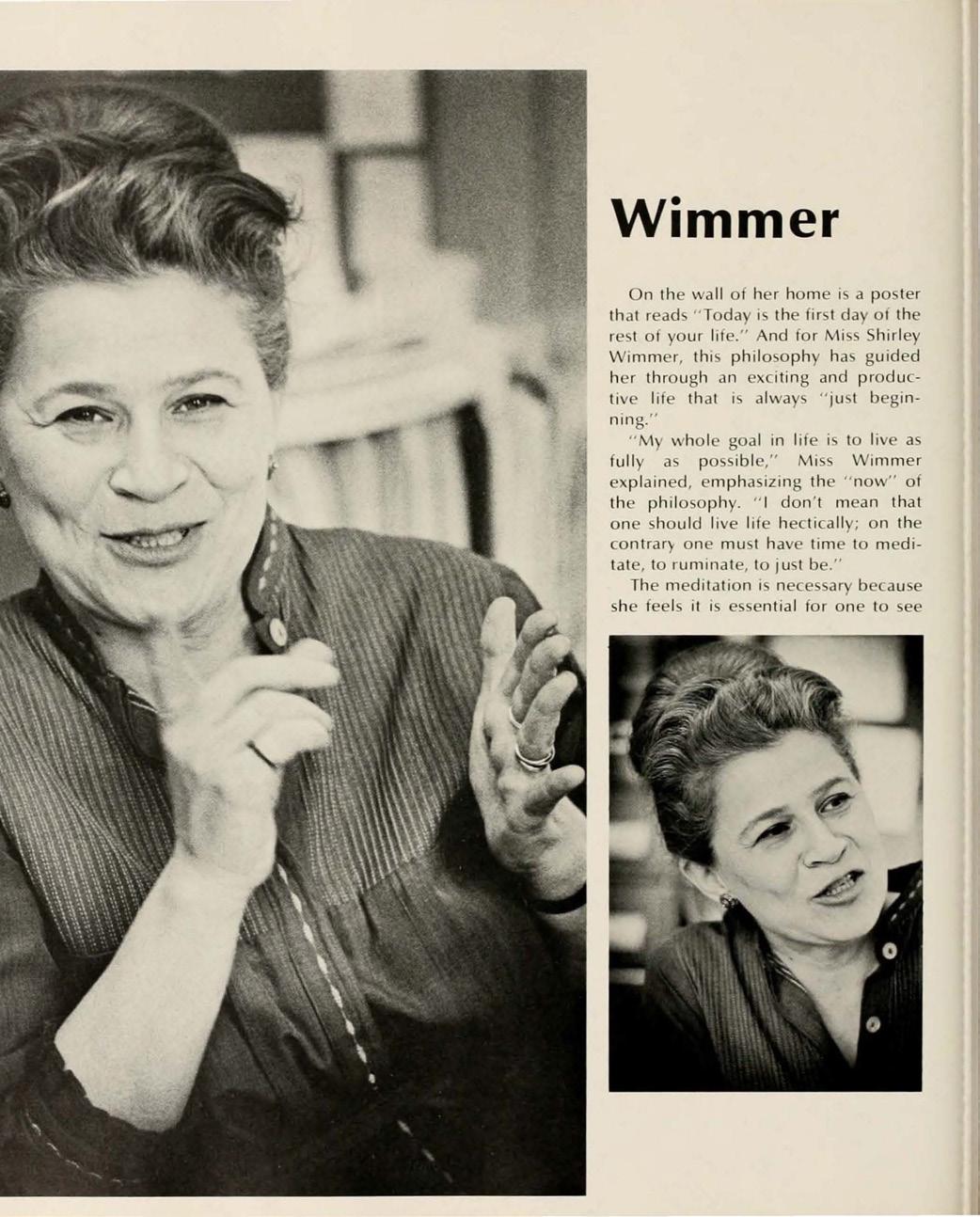

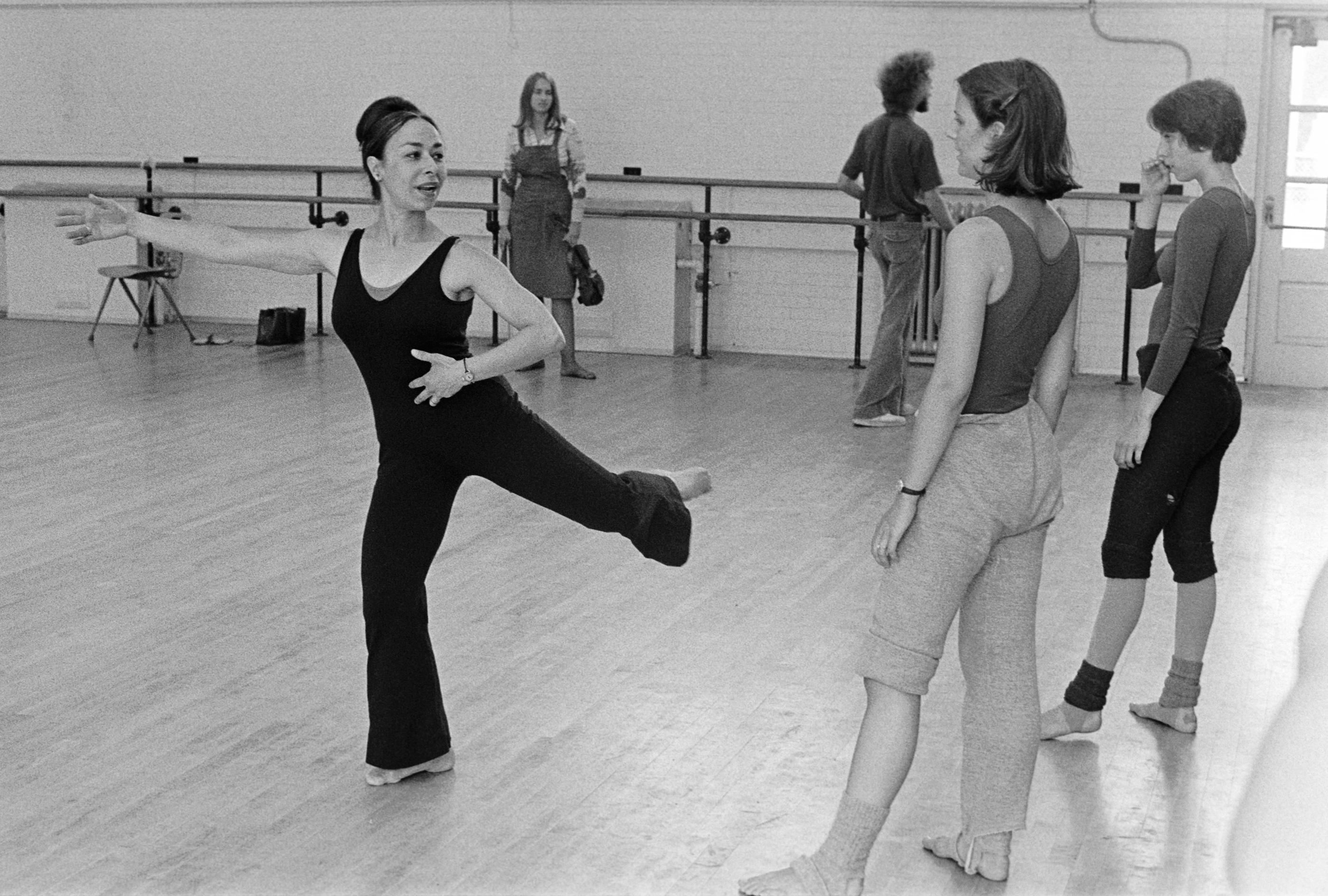

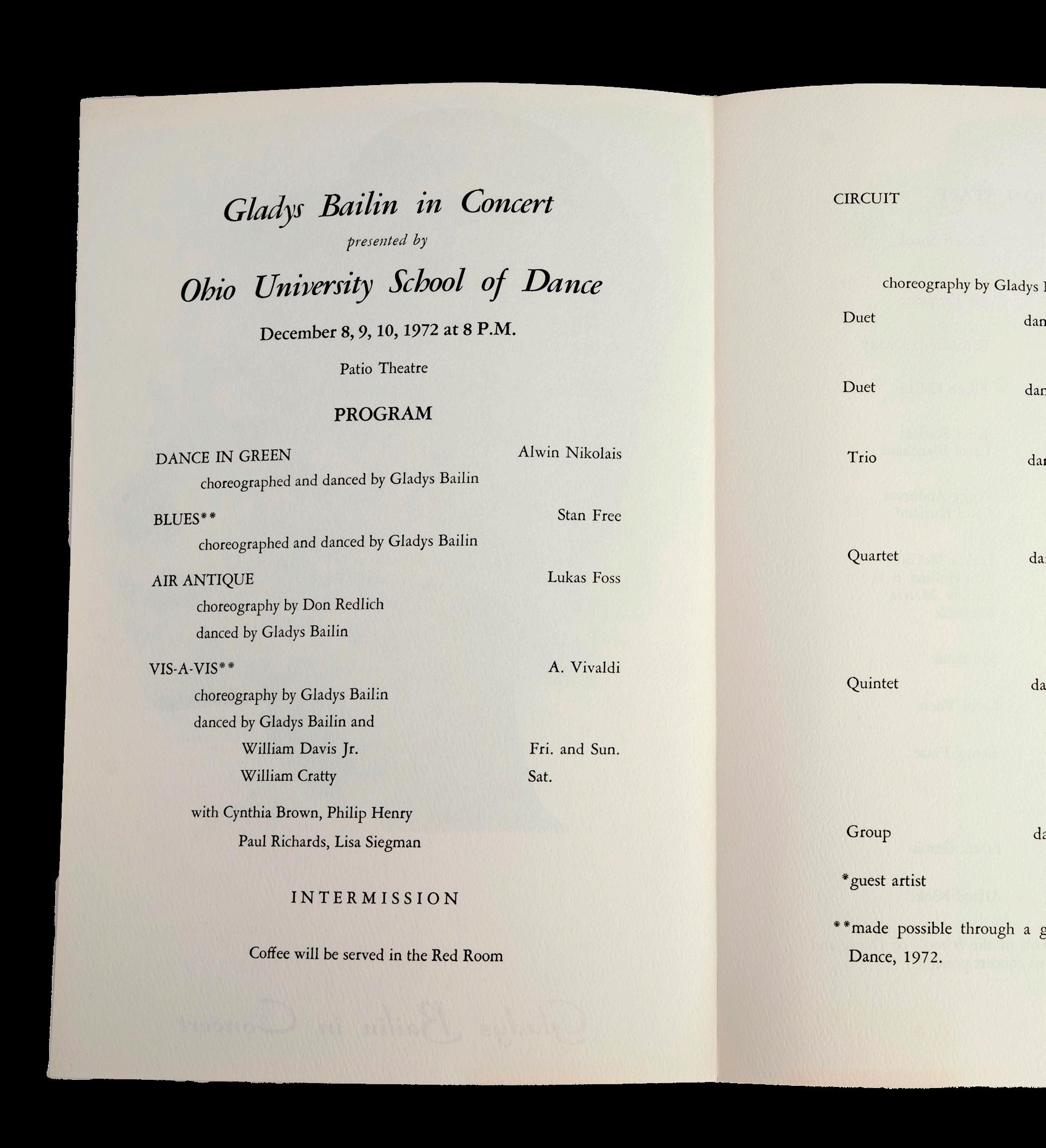

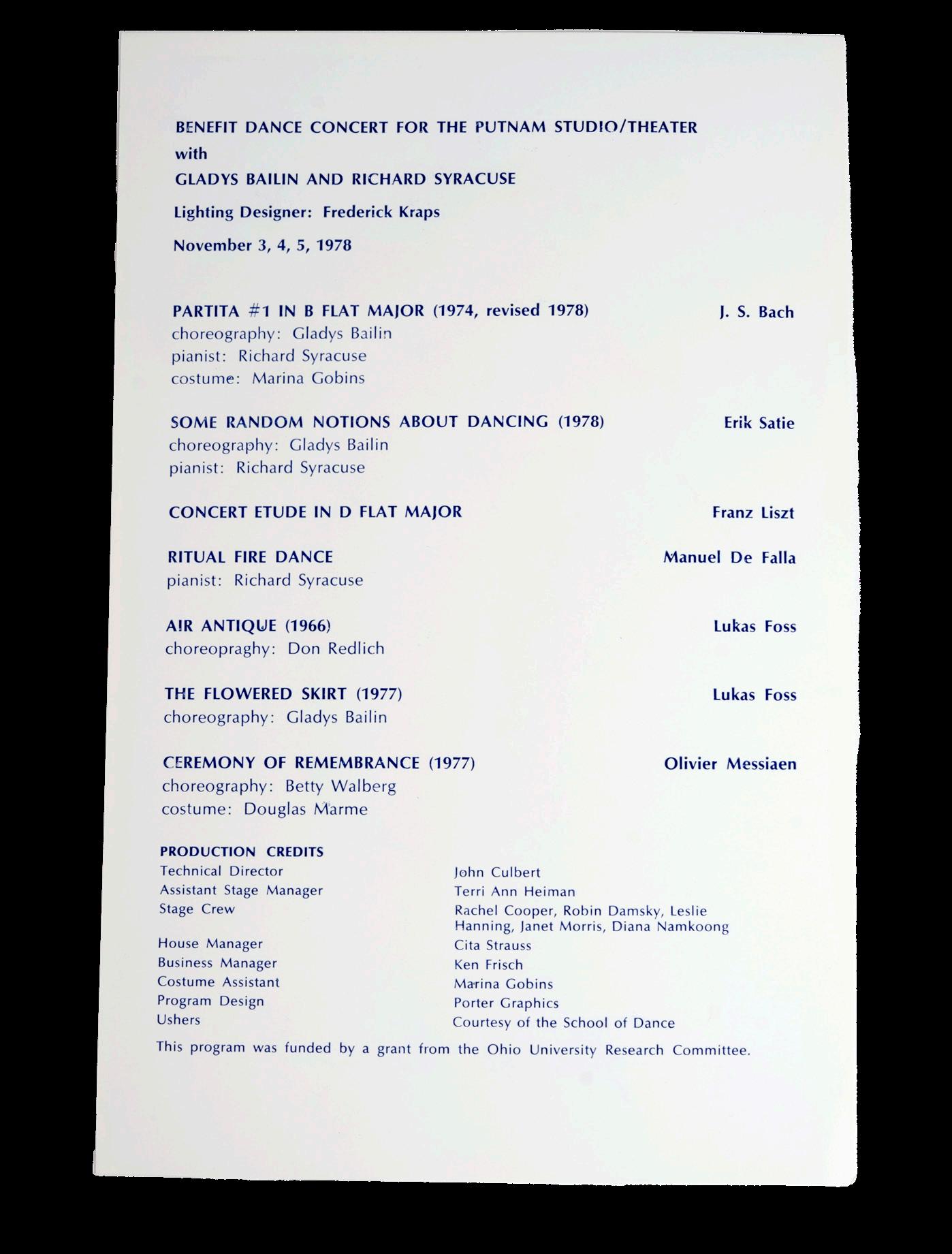

Ohio University was fortunate that Shirley Wimmer, founder of the School of Dance, recognized Bailin’s talents as a teaching artist and invited her to join the faculty in 1972. Bailin profoundly shaped the curriculum, giving the School of Dance a national reputation for an emphasis on composition as a rigorous creative activity and a conceptual approach to movement. By creating innovative dances –alternately abstract, light-hearted and deeply moving – for herself, her students and professional dancers, she provided an abiding model of curiosity and commitment. Her work has been funded by four fellowships from the National Endowment for the Arts and has been performed across the country.

Bailin provided key leadership for the academic study of dance in the 1980s and 1990s, a time of enormous growth for dance in higher education and has served as an onsite accreditor of higher-education programs for the National Association of Schools of Dance . She became the director of the School of Dance in 1983, serving until 1995. In 1986, she was the first woman to be named a Distinguished Professor of Ohio University, an honor that recognized the breadth and depth of her accomplishments in the field.

On September 9, 2022, Gladys Bailin was conferred an Honorary Doctorate of Fine Arts from Ohio University, which acknowledged her leadership, her deep knowledge of dance as an art, and her profound dedication to her students.

About the cover:

SCHOOL OF DANCE

Tresa Randall associate professor

Teresa Holland former administrative assistant

SCHOOL OF TELECOMMUNICATIONS

Andie Walla, associate professor

DEAN OF UNIVERSITY LIBRARIES

Rob Ross

EDITOR

Kate Mason coordinator of communications & assistant to the dean

UNIVERSITY LIBRARIES

Carla William music and special projects librarian

lorraine wochna former subject librarian for the performing arts

Kate Mason coordinator of communications & assistant to the dean

CONTRIBUTING EDITORS

Mimi Calhoun student communications assistant

Taylor Henninger student social media assistant

Tresa Randall associate professor in School of Dance

Greta Suiter manuscripts archivist

For more information on the collections, please contact Greta Suiter at suiter@ohio.edu

Allison Weber library support specialist

Carla Williams music and special projects librarian

DESIGNER

Stacey Stewart associate director of design, University Communications and Marketing

Very Special Thanks to Gladys Bailin for her support, the staff at Ohio University Libraries’ Mahn Center & Digital Collections — and to the many people who made this project possible.

Give today to help support University Libraries.

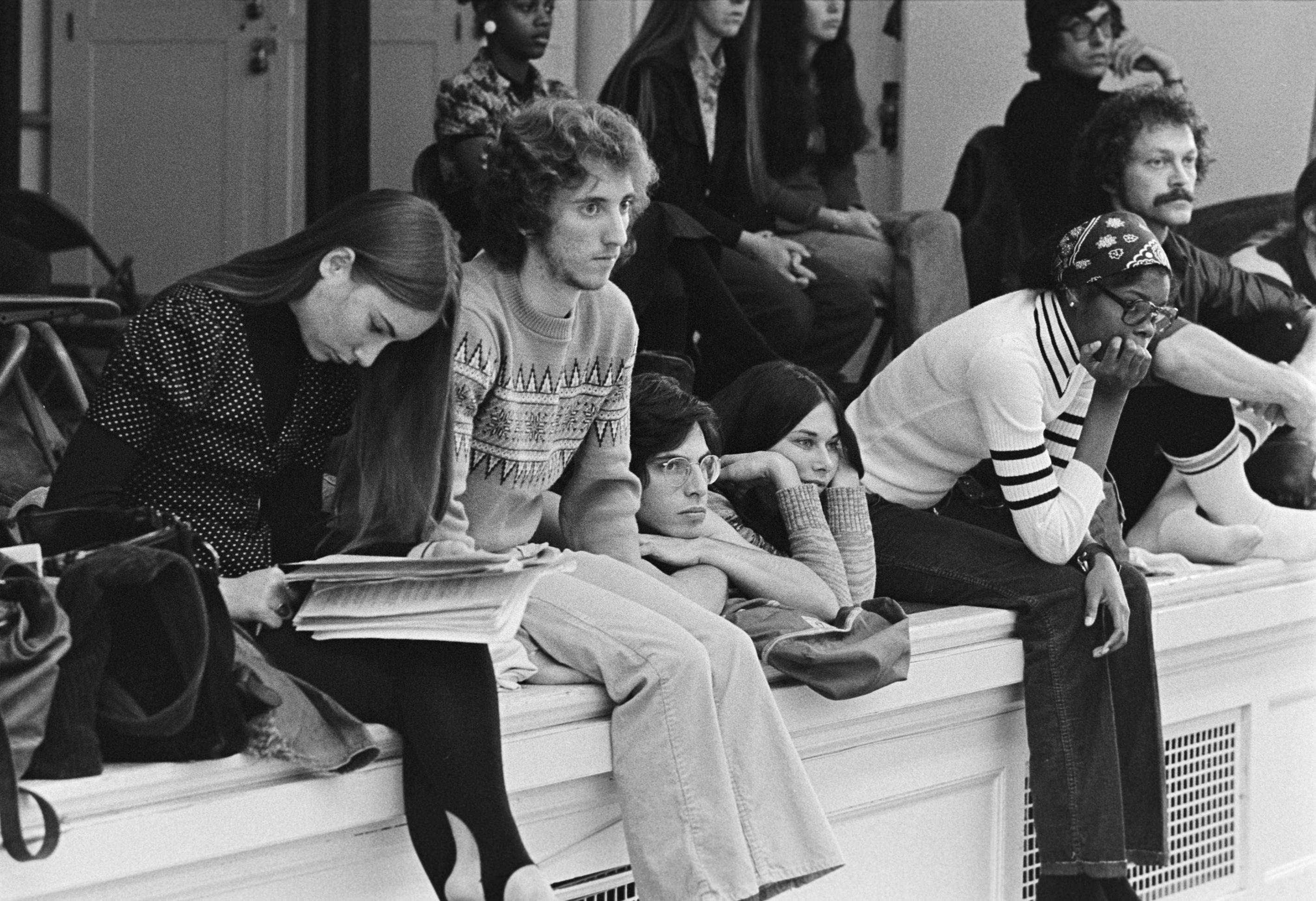

In early 2019, Dr. Gladys Bailin donated her collection of dance materials to Ohio University Libraries, now titled the “ Gladys Bailin Papers ,” that documents more than 50 years of her career in modern dance. Additionally, Bailin established the Alwin Nikolais/Murray Louis/ Gladys Bailin Archive Fund to preserve those collections for the future generations of researchers.

In October 2019, an Ohio University group of academics presented a proposal to the Dean of Libraries to create an oral history of Gladys Bailin. Those individuals are from the School of Dance, Tresa Randall and Teresa Holland; the School of Media Arts, Andie Walla ; and from University Libraries, Kate Mason , Carla Williams and lorraine wochna.

As the committee was just beginning production, the pandemic hit. So, it was necessary to revise the direction of the oral history project. The solution was to set up a recording studio in Gladys Bailin’s garage.

During the fall of 2020, one-to-two-hour audio interviews were recorded on four separate days: October 27 and 29 and November 5 and 10.

From those interviews, select audio content was then used to produce an insightful and revealing dance documentary film, “ An Interview with Gladys Bailin ,” headed by the committee, along with the creative energy of the School of Visual Communications graduate students, Brooke Stanley in graphic design and Billy Schuerman in photography. The film was later selected for screening in the “ 2023 Athens International Film + Video Festival ” and the “ 2024 American Dance Festival Movies for Movers .”

And here we are today, with the publication of those four 2020 interviews, which were edited for readability and clarity.

A very special thanks to Gladys Bailin, the team at University Communication and Marketing, the student communication team at University Libraries, the Mahn Center for Archives & Special Collections and Digital Initiatives team — and to all the other people who supported these projects.

Thank you.

1948 Begins studying with Alwin Nikolais at the Henry Street Playhouse.

Begins performing with the Playhouse Dance Company in dance plays for children such as “The Lobster Quadrille” and the “Shepherdess & the Chimney Sweep.”

Original performer in “Noumenon,” one of Nikolais’ signature works; premiers at Cooper Union, New York City.

“A dancer of great promise,” declares Louis Horst, influential editor of Dance Observer; faculty member Henry Street Playhouse; assistant director of Playhouse Children’s Workshop.

Member of Nikolais Dance Company; original performer in groundbreaking dance-theater works such as “Kaleidoscope,” “Allegory,” “Totem” and “Imago.”

Performs to critical acclaim at American Dance Festival in “Kaleidoscope” with the Alwin Nikolais Playhouse Dance Company.

Performs on “The Steve Allen Show,” NBC-TV.

Biographical portrait published in Dance Magazine; joins the Murray Louis Dance Company.

Performs in Spoleto, Italy.

Continues to perform with Nikolais Dance Com pany; Nikolais’ work, “Imago,” premiers in 1963 and soon tours internationally.

Featured in the important book, “The Modern Dance: Seven Statements of Belief,” by trailblazing dance historian Selma Jeanne Cohen; performs with Nikolais Dance Theater at Lincoln Center, at invitation of the American Dance Theater.

Tuesday

October 27, 2020

TR • Tresa Randall Interviewer

AW • Andie Walla Interviewer

GB • Gladys Bailin Interviewee

TR I am Tresa Randall, an associate professor of Dance at Ohio University.

GB I’m Gladys Bailin-Stern. That’s my married name. And I am a former faculty and director of the School of Dance at Ohio University.

TR All right. Gladys, we wanted to first ask you if you’d like to give a self-introduction. Tell us what you would like us to know about you.

GB I’m 90 years old. I have so much to say (laughing). We will have to edit that down (laughs). I don’t know, I think of myself as just an ordinary person who had an interesting life. And I’m very grateful because now I look back on it, and it is really kind of wonderful to feel as though one does not have regrets.

You know, to have done the thing you wanted to do is a gift in a way, a gift for my life. And it introduced me to places and people that I probably would never have experienced or met. So, it’s nice to look back and to have for the most part, good memories.

TR Thank you.

GB (laughing).

TR So, what are your earliest memories of wanting to be a dancer?

GB Oh, I was so fortunate when I was a kid. I lived in a great neighborhood of lower New York where there were lots of immigrants. And because of the immigrant neighborhood, there were lots of available opportunities. And my parents, who were not immigrants but never had much money, took advantage of many of the available arts activities that were there. It was not only the arts. We also did folk dancing and stuff like that. There was a music school, there was a dance school, there was theater, and this was all in a very relatively small area of New York City. When I visited several years ago, I hardly recognized [the neighborhood]; it’s all so changed. And because it was an immigrant neighborhood, it was made up of people from everywhere.

You’d just hear wonderful languages, mostly Eastern European, but languages from everywhere. When I went back, I heard mostly Spanish because it’s changed so radically. But it was a great neighborhood. I’m so glad that I lived there because I had availability of music lessons, dance lessons and theater lessons.

“New York City.” Newberry Library: Curt Teich Postcard Archives Collection. Internet Archive, 1943.

It was all within walking distance. And it was a time back in, let’s say late 1930s [and] early 1940s, where it was safe. One didn’t worry about a kid walking out alone, or could be snatched, or harmed in any way. So, there was a lot of freedom in a way that we don’t have [now], and kids haven’t had for a long time. So, I feel grateful for the time that I grew up.

TR Who were your first dance teachers?

GB Oh, Mimi Kagan. That’s a name I will never forget. She just had a way with children. I remember going to a dance class, maybe I was eight [years old], I don’t know, seven or eight, and she had such a charming manner. It was a joyous time. It was just something I would look forward to. That was probably more of an influence than I realized; I certainly didn’t realize it at the time. She made movement so accessible and fun that I couldn’t wait to get to class. And so, I remembered her name. I don’t remember some of the other people.

My parents thought that an arts education was really important. My father was an amateur pianist, and he was one of those wonderful people who you could hum a tune, and [then] he could play it. He could just translate it right away. Everything was in the key of C, but that’s okay. But there was a musical quality to my father that was terrific. And my mother, I think, was a frustrated dancer. She never had the opportunity to do things. But I have wonderful memories of family weddings when

I was a child, because there was always a lot of dancing at the weddings. And it was my grandmother [and] my grandfather who loved to get down and do all these old Russian things, you know (laughs).

But everyone in the family loved to dance. I remember there were wonderful ballroom dances that everybody knew. So, you knew the tango, you knew the waltz and you knew the foxtrot. And what was the other one? There was another one that I loved, which went out of favor, but it was some kind of a cross-legged thing that we would do in a group. We were sort of a musical-dancing family, but no one had training. Everyone had sort of a natural talent and certainly a natural ability. I think it rubbed off on me in some way (laughs).

TR So, you’ve addressed this a little bit already, but did your parents support your decision to go into the arts as a career?

GB Oh, yes. I had no problem with that. I think my mother was very happy that I [danced] as a matter of fact. [But] there was always this thing, [which] didn’t happen until maybe late high school years, when she said, “Well, I know you want to dance, but how are you going to make a living?” That was always her question. And she [asked], “Well, what else would you like to do?” And I would say, “Not much else to tell you the truth” (laughs).

But I did go to Hunter College, which was free at the time if you were a city resident. You had to pass a high school exam to go to a city college, but that was not too hard. They did not have any dance in college at that time, so my mother thought it would be a very good [idea] if I became a teacher. You know, there was something steady about that. But that was not at all what I wanted to do. But I took a couple of the teacher-training classes, and I really didn’t like them. So, I decided I would just do what they call now general education, and I was still going to dance classes after school.

So, I think back to those days and realize that when you’re a teen or even a late teen, you have a lot of energy. And boy did I have a lot of energy, because I went to school all day. I was able to arrange all my classes at Hunter College between the hours of 8 a.m. and 4 p.m. [Then] I would come home, have a quick something to eat and get to dance class at 6 p.m. The classes went from 6 p.m. to 10 p.m. every day. And then I’d come home and do homework. I don’t know how I managed it, but I did that for four years of college, and it sort of worked out.

Nik was very understanding. I’m talking about Alwin Nikolais. When he came in 1948, nine of us who were studying with him were either in high school or in college or we had a job. And he waited [for us] because classes were in the evening. Mostly, he was waiting for those of us to finish our jobs. At that time, you could do

a lot of what they call temp jobs, which was temporary work. [Now we call them] part-time jobs. This is pre-computers [when] people were hired as typists because that was the only way that things could be transcribed.

So, typing skills were important (laughs) because you could get a job for a few hours a day as a typist or copyist and make just about enough money to eat. And also, I remember [when] the subway was still a nickel at that time. So, everything was proportionately cheaper. When I think about apartment rentals, I can almost choke when I think about what I was paying for an apartment when I first got one to what that apartment is today. I mean, it’s thousands of dollars today when it was under $100 [back then]. I mean, it was cheap, you could get a place for $50 to $75 a month. They weren’t great, but they were within reason. But people weren’t earning very much (laughs).

So, where are we?

TR The question was about your parents supporting your decision.

GB Oh, my parents. I don’t have that much to say about them except [that] they were very supportive and not at all pushy about what I wanted to do. I think they saw that [dance] was something I was very committed to. My parents liked my dance friends, and since I

lived very close to the Playhouse where we had our classes, I would often bring friends home to my house because it was three or four blocks away. My mother did a lot of feeding of some pretty poor students who came to study with Nik. One of the things she always said [was], “Who are you bringing today, (laughs), [and] “How much do I have to prepare?” (laughs). It was very kind of her to do that.

TR Were you already involved in the Henry Street Playhouse at the time that Nikolais first came?

GB Yes. I had grown up in that neighborhood, so it was part of my after-school life to go there. I had never hung out with kids. I just wasn’t that kind of a young person who had girlfriends [that went] to the ice cream parlor [together]. I didn’t do that. I was always taking classes or busy with something. So, I didn’t have that kind of chummy relationship with girlfriends. I was always on the go. I was either at piano lessons, or dance lessons, or there was something to do at home. I never missed the kind of life that I see a lot of young people do where their friends become their family. That was never true with me. I was pretty

much a loner, I guess, but I never felt alone. I never felt lonely because I always had my dance pals.

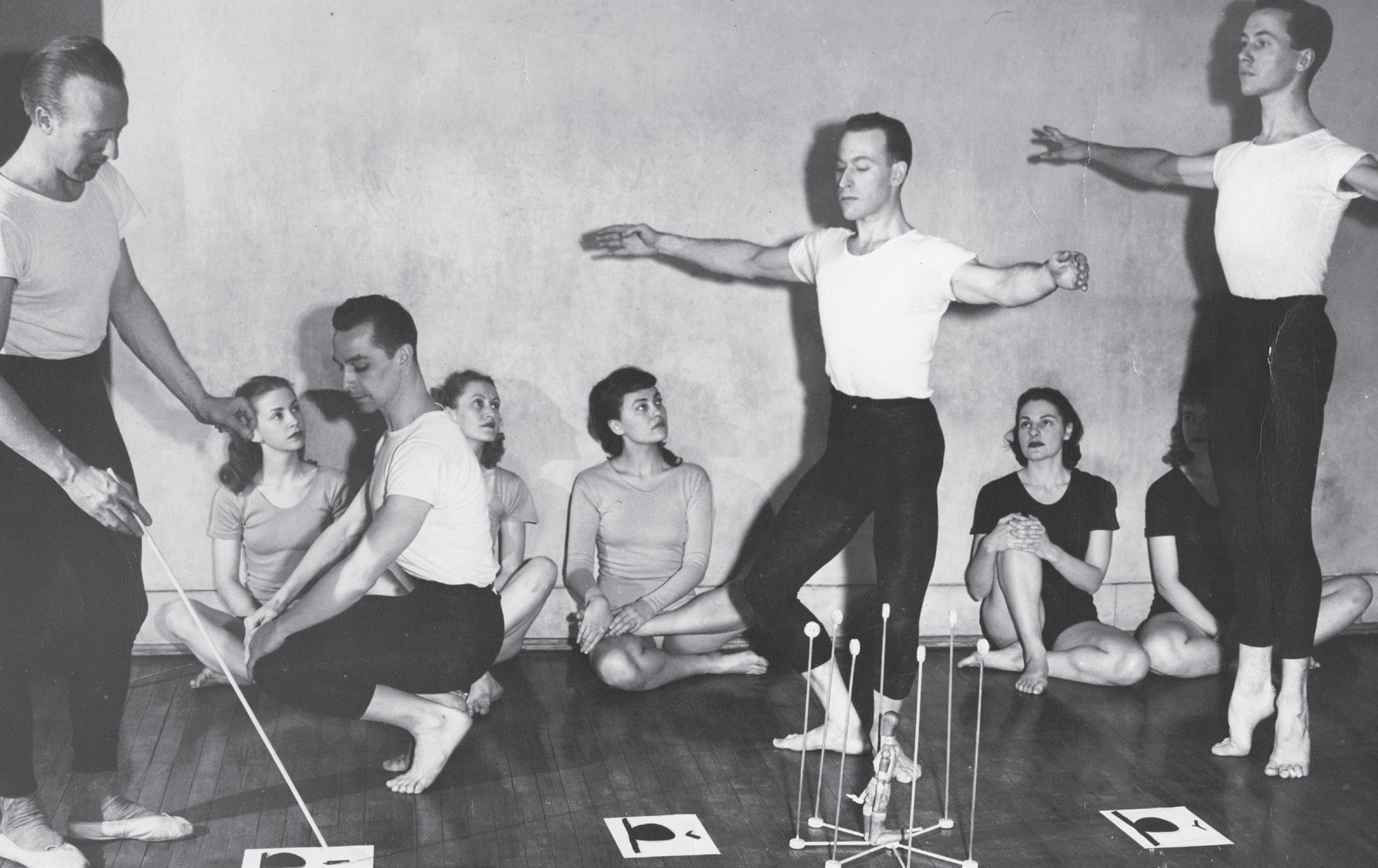

When Nik came to Henry Street to teach that first year that was a life-changing experience. It wasn’t just going to a dance class and then you forgot about it. This was a commitment. He never actually said it that way, but you felt that you had to make that kind of commitment if you were going to do anything with this man. He managed somehow to bring a group together that was a unit of people who were focused and dedicated to what he was trying to build. It was fantastic. This is the late 1940s, just

after [World War II]. There were lots of young men, who were out of the Army, who could go to a dance school and still [receive] the [same] kind of [funding from the GI Bill], that they would [if they] went to college.

Nik set this up. When I think back to the original set of classes, each class was like a college course, maybe even better. Because we were just focused on that. We didn’t have to share all these other things. There was a daily class in technique followed daily by what he called “theory,” but the theory class was either [that] he took an idea from technique [class], or he had another idea, and we would have improvisation. It was an hour of that, an hour-and-a-half [of] technique, followed by an hour of improvisation on whatever topic was on his mind, or whatever idea he wanted to explore. And I must say, we would have gone to Jupiter for him, you know? Because it was just so exciting to be a part of this man’s world. I’d never met anybody who was so creative, who had so much to give and gave it so easily and freely.

AW Can you say a little bit more about the improvisation? Did you just all get up and...

GB Oh, no, no, there was always something to explore. I called it improvisation, but there was always a topic. It was never just get up and do what you feel like doing. No, that he never allowed. It always had to have a point. And

you always had to have something you were looking to explore. It could be something as simple as your hand. And he would say, “Okay, we’re just going to do hands today.” And you would play around with your hand and find all sorts of things to do with your hand and make your hand as expressive as possible.

Or it could be your back. I mean, how much can your back do? But you would do this either alone or with somebody and sometimes with two or three people, and you’d have what I would call body conversations. We were constantly exploring movement possibilities. The thing that [Nik] really focused heavily on was that you didn’t do something you saw before, or something that you had done before. You were always exploring a new way, I mean, how many parts do we have? You don’t have any new parts, but you can [always] find new ways to deal with it.

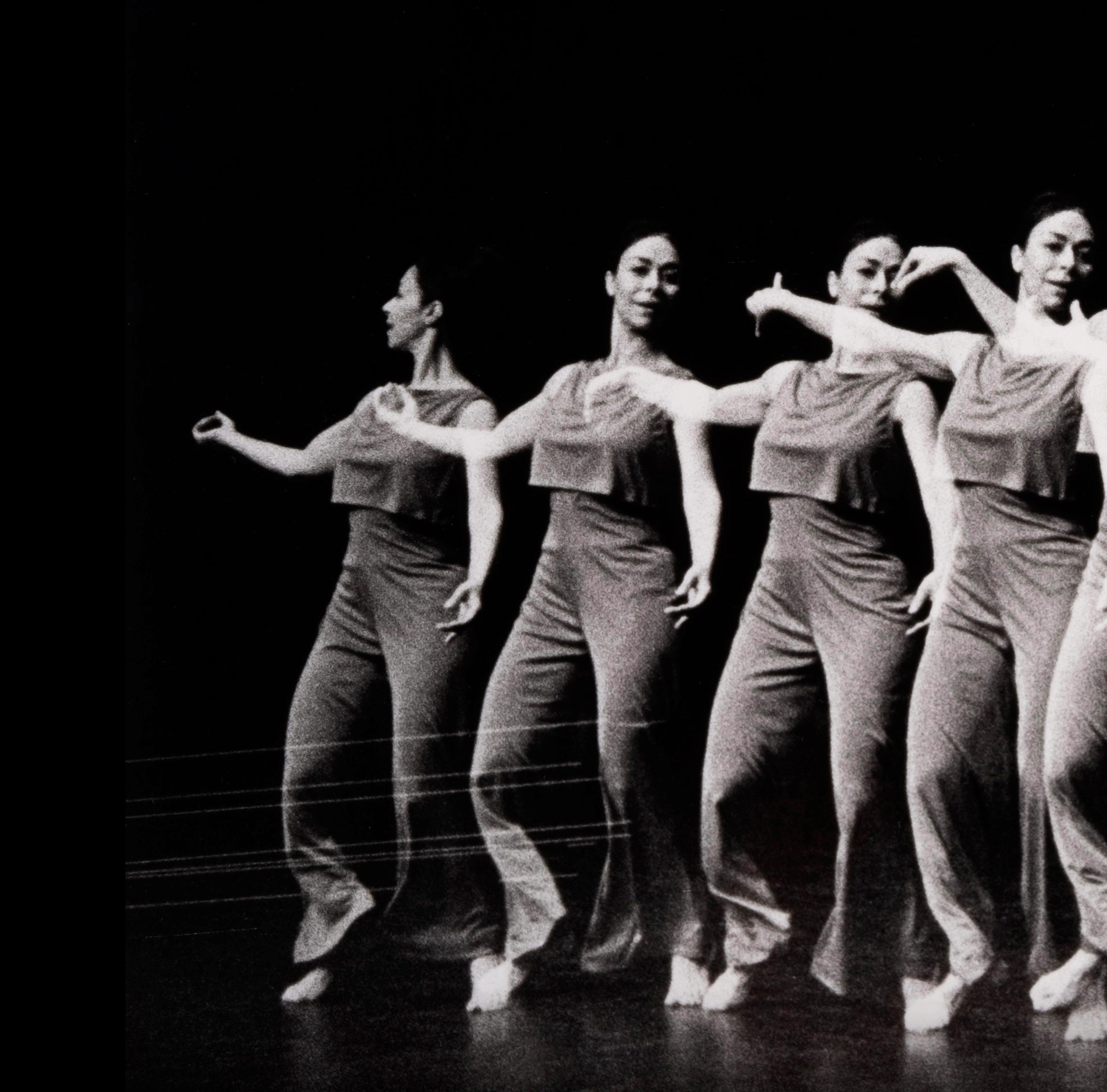

The possibilities were so enormous, because you had not only the range of time, or the range of space, [but] you also had the range of dynamics and tension or lack of tension and all of that. So, those became the bedrock, in a way, of his teaching. We would explore time in a myriad of ways. I mean, when you think of time, it’s gigantic. [There is] slow time, fast time, lagging time or whatever (laughs). I mean, time [has] so many possibilities, and you [just] couldn’t have imagined, but [Nik] would sort of [tease] that out of us.

[That was the] same thing with the way you could expand space, or decrease the space, or make the space tense, or make it loose or make it elastic. And [then] to play around with those ideas. And they were [just] ideas, and that, I think, is what blew my mind. I never thought of [them as] dance initially, you know, as young people, we don’t. We think of [them] as steps or a series of moves. But this man didn’t do that, he talked about ideas. And you would translate these ideas into your body and into the movement. And the possibilities were endless, and they were unique to each person.

The other thing that was so interesting during improvisation was that you would have different experiences with different people, because the other members of the group would have their own ideas of what it was, and then you would have interactions with them. And so, you wouldn’t do the same thing with each person. You would find that you are responding in a different way. It was marvelous, and it was a wonderful way to explore your own body, and to explore the whole world of movement possibilities. Sometimes, if you just admired what somebody else was doing, you would try it on yourself. And they would try on something that you were doing. And in a way, you would begin to expand your own vocabulary and your own understanding of movement.

So those classes in the early days were invaluable. I guess, it somehow made dance a real art form because it now had a structure, it had ideas behind it, and it wasn’t just something you did because it felt good. And now [with Nik] there was a real program, in a way, a real set of principles and a set of ideas that you can start to deal with. Once that happens, it opens all sorts of creative possibilities. And that’s basically where [Nik’s] focus later [went]. Classes in choreography were basically creative explorations, which came out of the improvisations, but they also came out of assignments that he would give.

And they were exciting. Nik was always very positive. I don’t remember him ever being a negative person. So, people would bring in all sorts of things at different stages of [their] development, sometimes [they were] little ideas that hadn’t been developed at all. And he always had something positive to say, which I must say, I didn’t always pick up [that attribute] as a teacher myself (laughs). But I always admired that he could do this (laughs). He was never harsh and always found a way to somehow bring you along, even the least talented of the group. And [there were] all sorts of people who would come and go. You know, a lot of people [just] didn’t continue. You had to be really committed to do it.

But when [Nik] set up a regular training program, you were committed to that. It was

like going to college, except you just didn’t do it for four years and then leave. You just did it. Eventually, what came out of it was not a diploma but a dance company. And so, in a sense, that was your diploma (laughs), if you want to look at it in those ways.

TR Mm-hmm (affirmative).

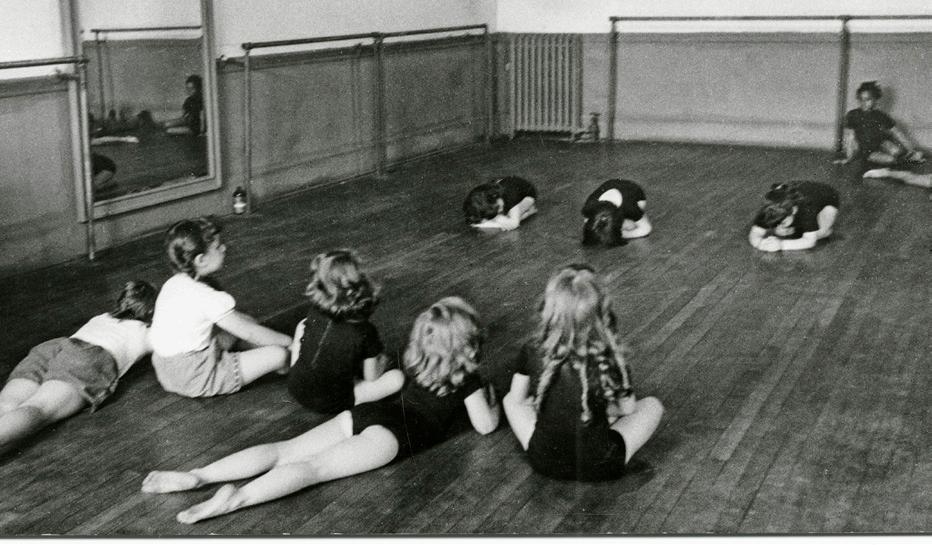

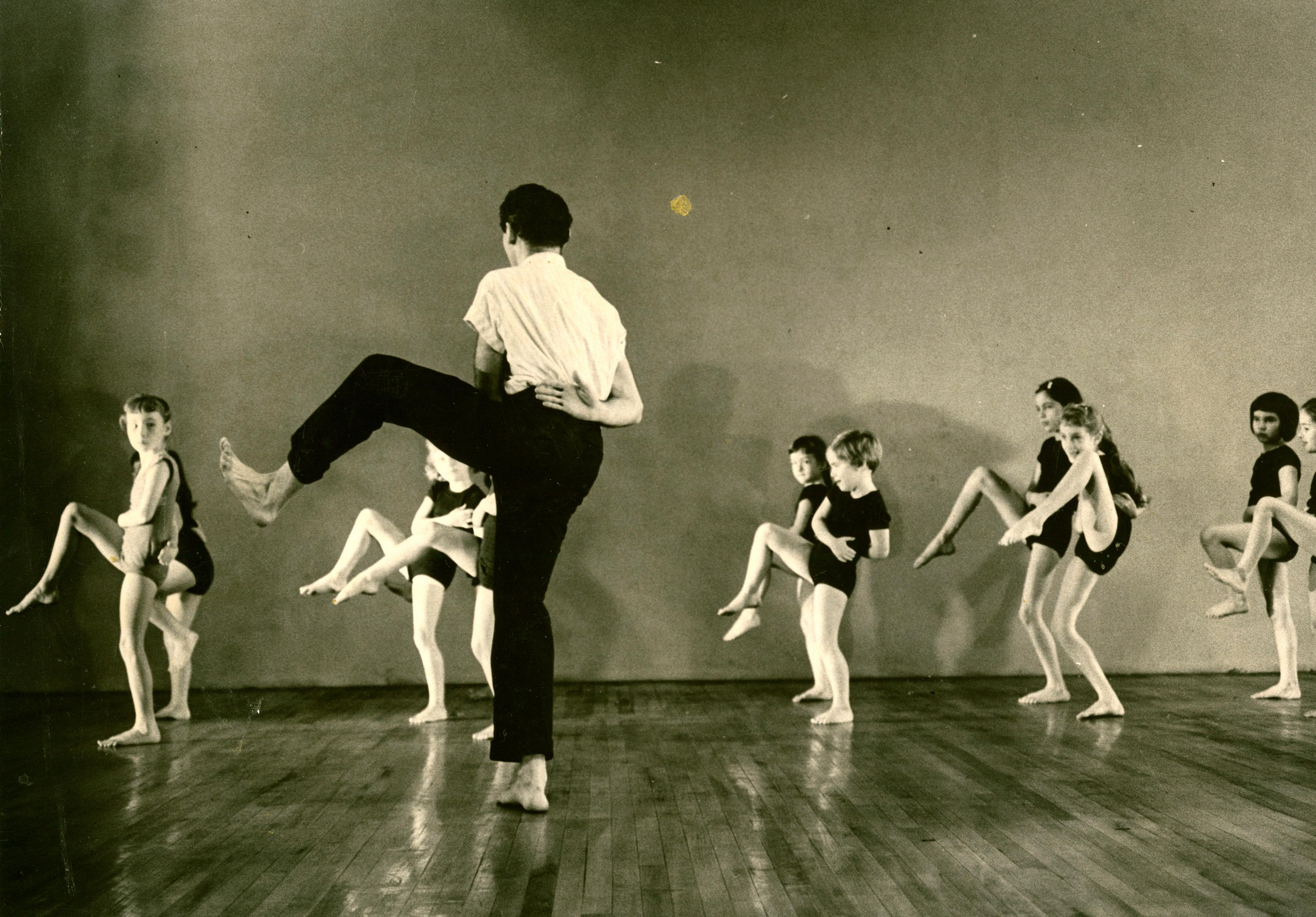

GB Even from the beginning, Nik knew that you cannot be a dancer [if you are] just a studio dancer. That you must have performing opportunities to use what you learn in the classroom. And so he made performing opportunities, which was also part of his mission at the Henry Street Playhouse. The Playhouse was supported through some community funds, and the charges for [taking] classes were minimal. I don’t know how he got paid, to tell you the truth, I never knew that. But he had an obligation to the community. So here [at the Playhouse] he had a whole group of young people, mostly GIs and a few females. And he decides, “Okay, we have to do something for the community.” So, he started making a series of children’s dance plays, which we performed at three o’clock on Saturday for a nickel.

And an adult would have to come with a child. You could not come [alone] you had to have a child with you [at a cost of] five cents. I mean, the subway was five cents at that time. But you know, it was a fantastic

Above: Children and adults seated at the Playhouse.

Photography by David Berlin. Nikolais & Louis Dance Collection, Ohio University Libraries, Nov. 10, 1955.

Left: “Hansel and Gretel,” choreography by Murray Louis.

Photography by David Berlin. Nikolais & Louis Dance Collection, Ohio University Libraries, premiered Feb. 12 1958.

opportunity for us. And the things that he made were so charming, I can’t begin to tell you. Some of them had voiceovers, some of them we had speaking roles. Sometimes, it was just music, but they were charming. One was the “Lobster Quadrille” from “Alice in Wonderland.” And then others were things that he made up. Some of them were fables. But they were acting and dancing [roles]. They were both parts. Sometimes we [even] had speaking parts.

But [children’s performances] brought the community in. They were 15-minute stories, and you’d put three of them together, and you’d have a little intermission in between.

For a nickel, it was a great afternoon’s entertainment (laughs). And the parents liked it more than the kids. They were very successful. And there were people who came out of the community to see what was going on in this little theater in downtown New York.

They became very popular, and we had to tour them after a while. I remember us getting a truck, and we had scenery and things like that too, and we took it out and played in some of the schools. And that was our little tour of the city schools, which was a nice way to get it out.

It was kind of an interesting opportunity for us because we would have to set up in whatever space was available in the school. We had to

learn to be very creative about the spaces that we had. Anyhow, there are some fun stories about places we went to, and the children being so unruly sometimes. They would throw chewing gum, and they would throw all sorts of things. I mean, they were just badly behaved children at those young ages (laughs). Maybe they were forced to come to the theater. I don’t know what it was. Not all of them were terrible, for the most part, they were okay. But I do remember some very unruly kids (laughing).

TR (laughs)

GB Those were not only charming plays, they were [also] performing experiences. And they were not always the easiest because we had to set up, [and] we had to learn how to do that in a hurry and, you know, make it all work in whatever space we were in. And it was great training to be so adaptable to whatever the circumstances required. [We] did that for a few years, and then we sort of outgrew it. And then [Nik] started to do more concert work.

Basically, he was waiting for us to grow up and become more trained so that [he] could [focus] on other things.

In addition, there was a kind of wonderful generosity there. When I think back, it was Nik’s work for the most part, but he encouraged us to do our own work. And if he thought [your work] was reasonably okay, sometimes he’d put it on the program. So, there would be a shared program of his work and sometimes our work. Very few of us did group works at that time. Most of us were

working on solos or duets with each other, because we had each other.

I can’t tell you what fantastic training that was, [which] grew out of the necessity of being at the [Playhouse], and Nik’s need to do things in the community. That was fantastic training for all of us to be so malleable in a way [and] to do all that. So, I treasure those early years. They were an incredible training ground. After a few years when we had more experience under our belts as performers, he started to encourage [us to do] our own [choreography] a lot more. He was so generous.

After a couple of years, he would simply say in the classroom, “Okay, Murray...” that is Murray Louis I’m talking about, “and Gladys, you have a date in April. Put a concert together.” I mean, [what a] tremendous responsibility, but you would do it. I mean, you would have the theater for yourself, [and] you would [choreograph] your own thing. So, Murray and I would work on our solos, and then we would figure [that] maybe we should work on a duet together, and then maybe we would bring in a couple of friends, and [then] we would work on a little trio here and there.

We didn’t [choreograph] anything big because no one had all that [much] free time to do it. And besides, we had no experience on how to deal with larger groups. Nik was good at that.

He was very good (laughs) [working with] large groups. But you know, you start small. You start with duets and trios, and [then] you end up later doing these other things. I think back [now about] what a gift it is to your students, you know? It was not a huge crowd of people, but if Nik saw that you were serious about it, he would give you those opportunities. And then, the theater was right there, so that was not a problem. Nik would often be the lighting designer himself, [as well].

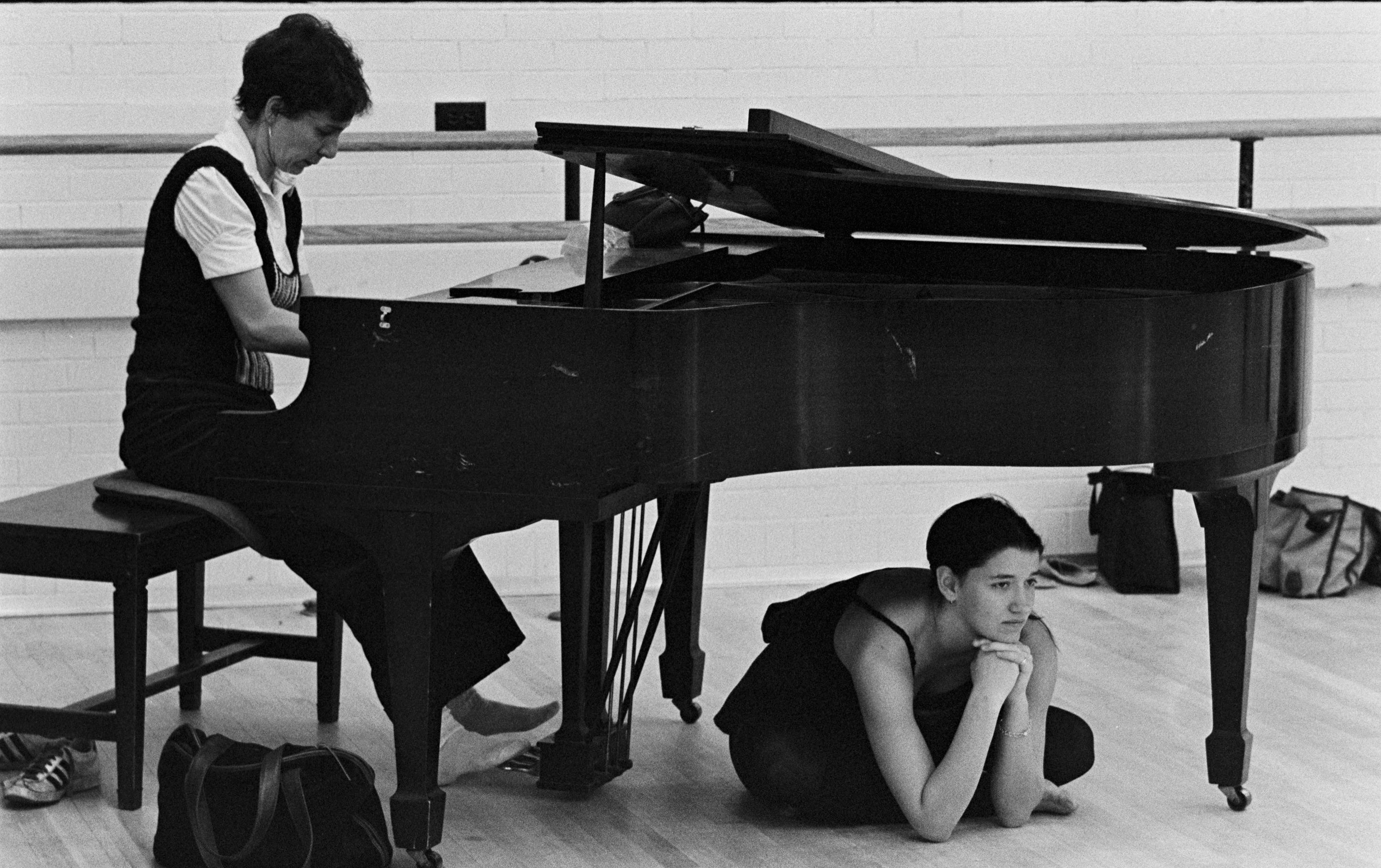

And then we would have had to make our own costumes, and Nik would check [them] out saying, “Yeah, let’s see [what you have].” He just had a wonderful theatrical eye. So, you could say, “This is what I’m thinking about.” You would have put something together [for a costume], and he’d say, “Yeah, that’s not a bad idea. Let’s do this, [or let’s do that].” You could trust him on so many theatrical levels. In addition, if you did not have good music [to accompany your dance], he could always play the piano for you, because he was also a musician.

It was a special time. It really was unique. It could never be repeated.

TR You provoked so many follow up questions. You were talking about the GIs and how a number of the dancers were on the GI Bill.

I believe that at least one of them was African American, which at that time was pretty unusual [to have an integrated dance school.]

GB That was unusual. Bill Frank was a Black guy.

I don’t remember how Bill actually came [to join us], but he was a big strong untrained person who had just an enormous desire. And Nik liked him, and Nik kind of pushed him. He became a lovely mover. I mean, there’s a photograph of him and me that’s so beautiful. It’s in [one of Ohio University Libraries’] booklets.

TR Yeah, I saw that. It’s amazing.

GB Yeah.

That [photograph] is really stunning. [Bill Frank] was very strong, and he was a marvelous partner. So, if you needed a male partner to lift you or do things, he just made you feel like you were a feather because he was so able. He became more and more refined as a mover as he trained more. He never talked about himself, but [I know that] he was not one of the GIs. He was just someone who happened to come in [to dance]. It was unusual, because we didn’t have very many people of color at that time at all.

TR Mm-hmm (affirmative). Yeah, that was why I wanted to ask about that, because obviously the dance world is really concerned right now | 23

about anti-racism, and segregation is still a problem in the dance world.

GB Oh, yes. It was very prevalent in the 1940s [as well].

TR It seems to me that Nikolais doesn’t get enough credit for being ahead of his time.

GB Yes, he was. Coral Martindale was also a Black dancer in the company at another time, [but] Nik didn’t care. I mean, he was not making those [kinds of] decisions. If you could move, and you could improvise, and you could do it, and you could give your time, and Nik thought you could enhance the company, [Nik accepted you]. It had nothing to do with the color barrier. I’m sure it was difficult for [people of color]. There was only one time that I remember where the color barrier sort of hit me in the face. And it was on a small tour that we did in the South.

Everything was fine in the theater. We went out to dinner afterwards, and because Bill [Frank] was with us, we could not go into a restaurant. I mean, when [we were] in the North, it was not a problem, but when you’re in the South, it was a whole different story. So, we went to the restaurant, and we were turned away. And it was shocking to us.

GB That really hit home to me. That was something, having been brought up in the North and not experiencing it [before. That] shook me and

everyone else. All of us, who were born in Brooklyn around that [time], just never even thought about it. But boy, it was a whole other story when you go south of the Mason-Dixon line. So, that was something we had to be very careful about.

TR Mm-hmm (affirmative). Yeah. Another thread I wanted to follow [up with] was [that] you mentioned Nik had his own theater. It seems to me that a lot of his creativity with set design and transforming the performing space the way he did, was because he had access to his own theater.

GB I agree.

TR Do you want to talk about that a little bit?

GB I think it was unique to have classes on the stage, [especially] when I think about the two studios that were upstairs. I went back some years ago to look, and I said, “Oh my God.” We used to call this the big studio, [but] it was really small. I mean, maybe it was a little bit longer than [my garage], but you know, you take two leaps and you’re across the floor. That’s not like the big gymnasium that we [currently] work in [at Ohio University]. I don’t know, we just did it all. We did everything in Henry Street, either on the stage when it was available as a studio, or the two smaller rooms upstairs. One [studio] was smaller than the other, but this was where there were classes.

There was [also] a little vestibule there, and on Saturday mornings all the parents would sit out there because of the Saturday classes for children. [And only] one bathroom (laughs).

TR (Laughs)

GB I don’t know how it worked. I mean, they made it work (laughs).

TR Do you think that the location on the Lower East Side affected the kind of work that Nik did? Did the community environment affect it?

GB I don’t know. I mean, I just called it an immigrant neighborhood, but I don’t know if it was the neighborhood. I think it was the theater. It was the fact that the building had this beautiful little gem of a theater with 200 seats, [maybe] 250 max. Probably the size of the Patio Theater here [at Ohio University] or similar to that. I think that’s what attracted Nik, and the possibility of some training studios up on the second floor.

The [Playhouse] basement was a pretty awful place. I never liked going down there. Eventually, it turned into a costume shop [after] it got cleaned up. But it was gross for a long time. It was much better once things got going. Nik [eventually] needed to hire a costumer and [other] people to do all those unusual outfits that he designed, which had to be specially made for [us]. They were not store-bought things.

TR Mm-hmm (affirmative). So, which of Nik’s pieces were your favorite to perform?

GB Oh, I will have to think back to the repertory. It’s been so long ago.

TR I know (laughs). I have some photographs [that] I can pull up on my computer that might help jog your memory (laughs).

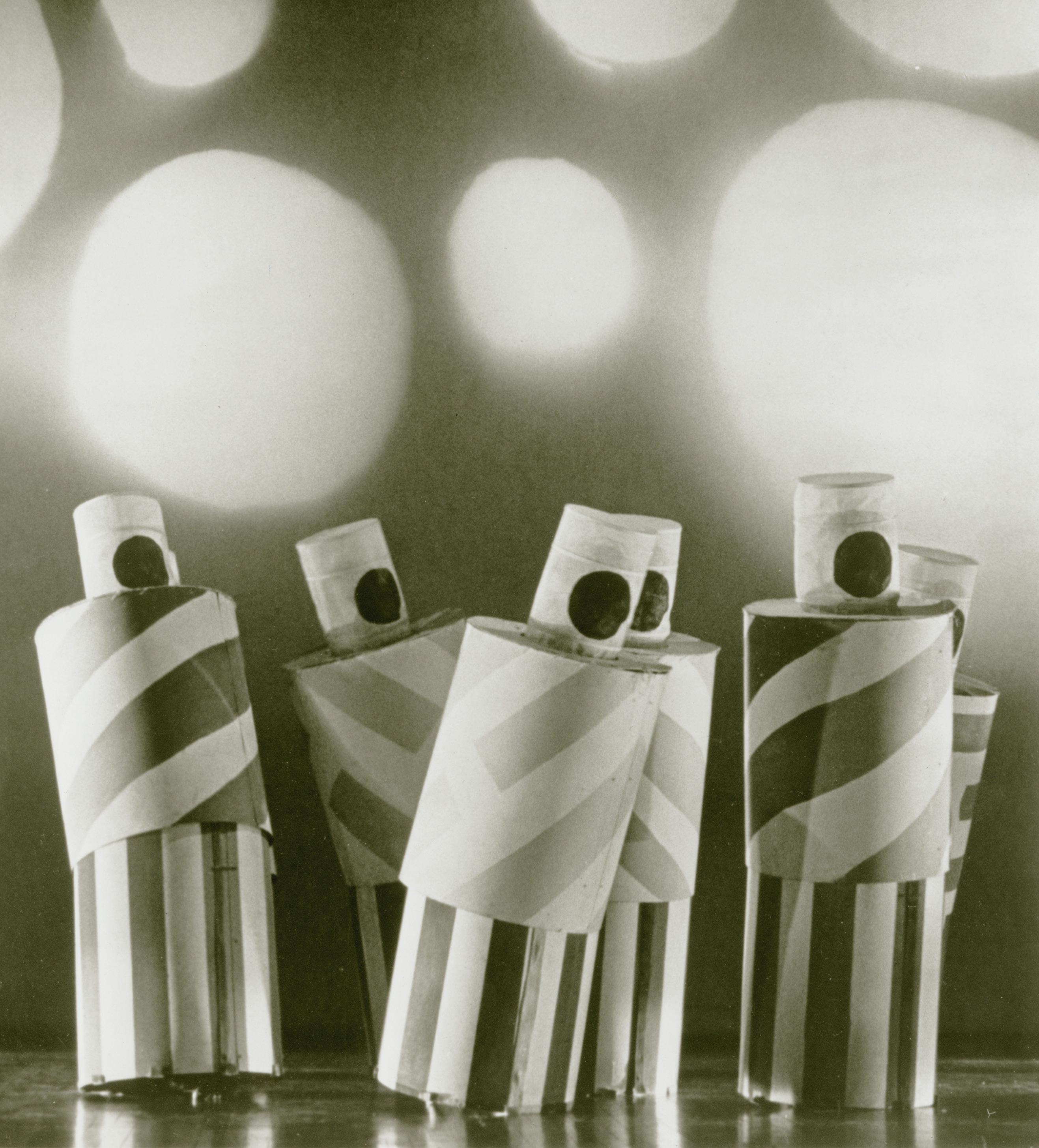

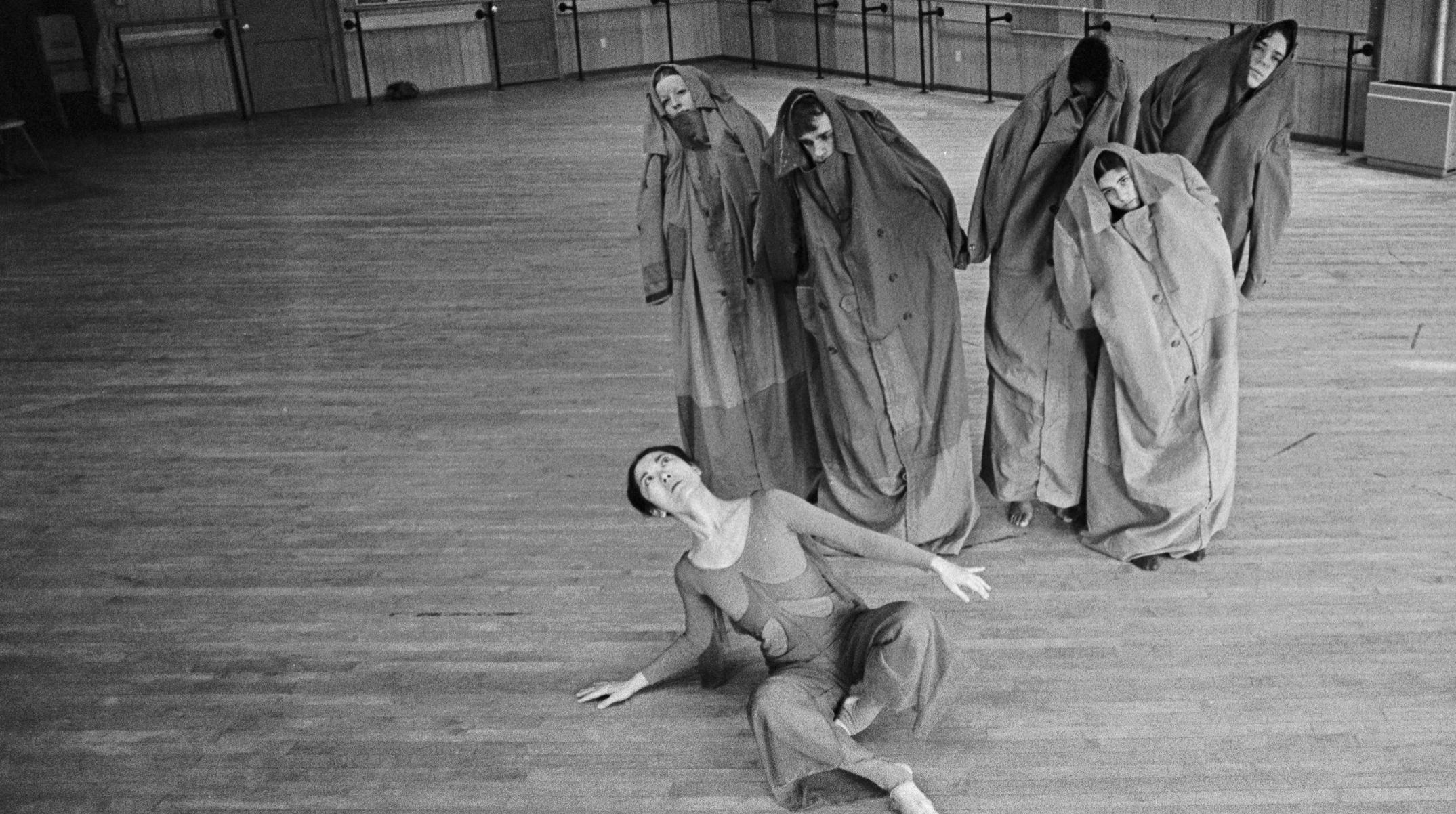

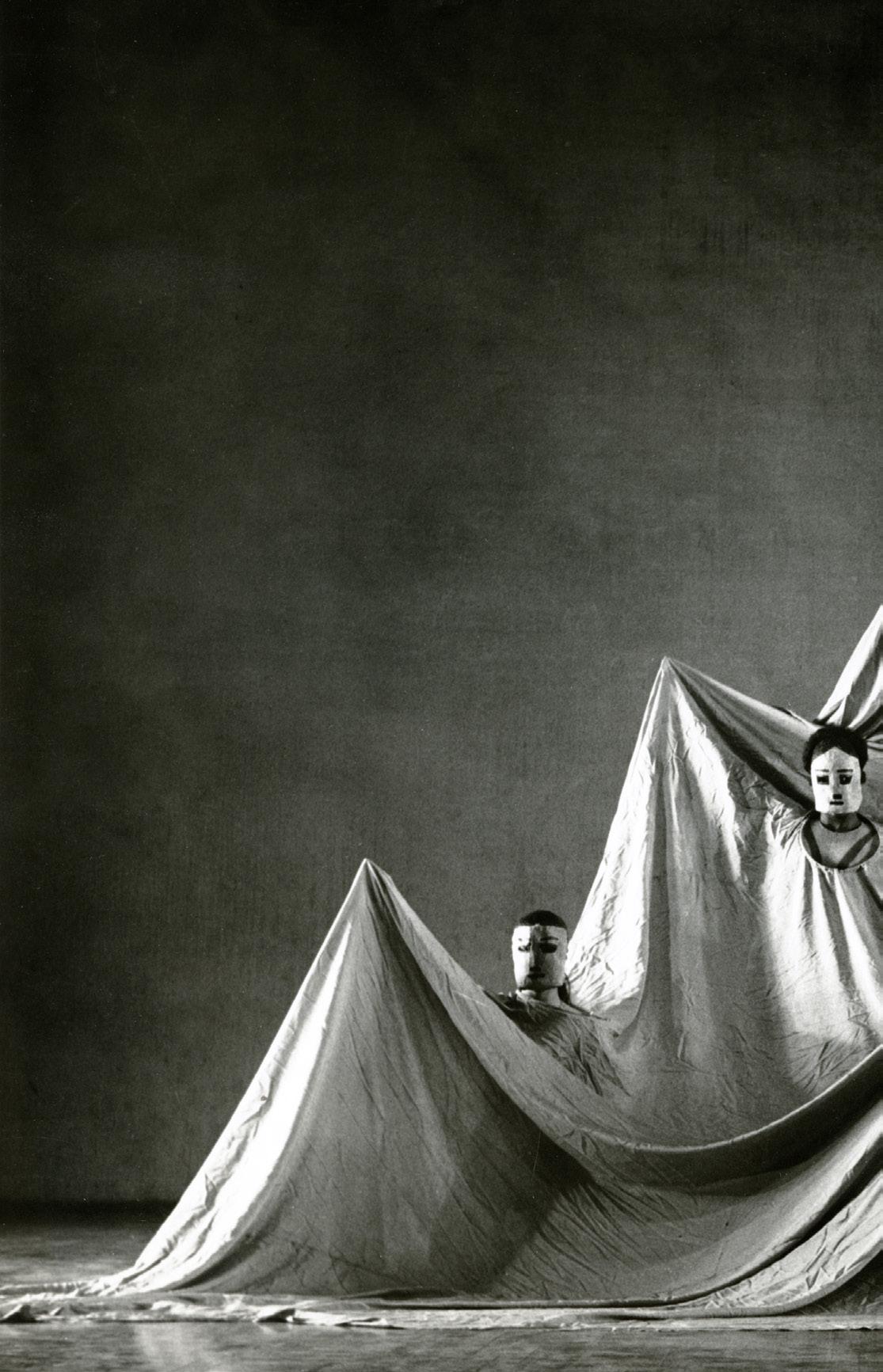

GB You know, [when] I think back, they were all, in their own way, challenging. I think the one that was probably the most challenging (laughs) was the one when we were inside bags. First

of all, it is a blow to your ego. I can remember saying to Nik, “My mother won’t know who I am (laughs) once you cover [me] up.” But he was not interested (laughs). He was interested in shapes that [the bags] could make. So, you got over your ego stuff right away (laughs). There was a lot of times that we were covered up.

TR Mm-hmm (affirmative).

GB And it was always for artistic purposes (laughs). So, you would have to leave your ego at the

door when you worked with Nik. And he did not like putting up with people who felt [that it] was more important that they be seen fully. [From Nik’s perspective], they were not good company material. So, the people who stayed with him were always more willing to give up their personal ego for the [creative] work that he was trying to do. And it was a wonderful time because no one was doing that kind of work. So, you felt you were really a part of the avant-garde.

And I remember, some of the early reviews [of Nik’s work] were not very good. [But] people came, and [Nik’s work] started to attract critics. They had not seen this sort of thing [before]. Most of the dance of the late 1940s, 1950s was pretty much about the world, not necessarily about movement. [Choreographers] had to make their statements. When I think about the work in the 1940s, I think the only person who was not doing that was Martha Graham, who was doing Greek tragedies and Greek myths.

[Anna] Sokolow and some of the others were very into the [Great] Depression and the war years, you know, the current events of the day. And here [was] Nikolais, [who] was not talking about current events, [but rather] he was doing something abstract, and that was not popular at the time.

[Visual art] was not necessarily [just] a figure, [but rather] it was color, it was shape, it was all those things. It had nothing to do with being figurative. And Nik was very much a part of that abstract expression, not expressionist so much, but abstraction.

He was a wonderful example of that. Even down to the costuming, down to the whole look of it. You know, there were stripes and bold shapes and things of that nature. And it didn’t look like something you saw in life. They were more imaginative, I suppose. I don’t know what else to call it. Some people called ”Galaxy,”

it “out of space.” But how did they know? No one knew what outer space was. They would call us creatures from outer space because they would imagine maybe that is where we lived, on Venus or something (laughs).

TR (laughs)

GB I mean, [critics] couldn’t pin us down, and they could not use the same language in their reporting as they could for [Martha] Graham or [Anna] Sokolow. It was a different language. And I think that was the problem. They didn’t have an abstract language.

TR Mm-hmm (affirmative). Yes, I was going to ask you about when Nikolais premiered “Kaleidoscope” at the American Dance Festival?

GB Oh, yes.

TR And I know it provoked a big controversy. So, do you want to talk about that?

GB Oh, it was wonderful to be a part of that, because there were [different] camps. And you could tell the people who thought this [choreography] was just the most unusual thing they had ever seen, and they were screaming [about it]. And the people who hated Nik’s [work] with a passion because it

didn’t look like Graham (laughs). There was no middle [ground]. You had to be either in the camp of the “new” or the camp of the “old.” And Nikolais just let it all happen. He just went about doing what he needed to do. It was wonderful in that way. You know, to just do your thing, and just keep doing it. Then people sort of accepted it. And now some of [Nik’s choreography] looks like old hat, you know. It’s amazing how our tastes change once things become familiar and you are no longer surprised by it at all, or even repulsed or excited. You just say, “Oh” (laughs).

TR I am always continually amazed though that even students today, and audiences today, when they see Nikolais’ work, they still think it’s strange and out of the ordinary. It is still fresh.

GB That’s nice to know.

Yeah. I don’t know if people have the ability now. Certainly, they don’t have all the accoutrements, you know, like having a theater, and having your own designer and all of that. [I don’t know] whether or not it is even possible to do today. Everything is too expensive, and I don’t know if they have the freedom to do that.

“Kaleidoscope,” choreography by Alwin Nikolais. Photography by David Berlin. Nikolais & Louis Dance Collection, Ohio University Libraries, premiered May 27, 1953.

Mm-hmm (affirmative).

GB So, it’s unfortunate. I know that there are always attempts, at least the attempts of being different and so forth and so on. [Choreography] has become much more pedestrian, so they threw out the whole idea of theatricality, partly, because it is not affordable. But the other thing is, I think just people went the other way. I remember, maybe it was, the late 1960s perhaps, when there was such a revulsion against anything theatrical and stuff like that. The sort of “back to nature” thing, [such as choreography by] Yvonne Rainer and her crowd. People would just get on stage and walk, and I’d say, “Oh my God, this is boring?” You know, boring. It was getting back to simplicity.

I remember so clearly when the students would pick up that [style]. I was teaching at NYU, and I said to them one day, “Let’s all go to the window and look out on the street, okay?” And we stood there for a while and watched people on the street doing their ordinary thing. I said, “Would you pay a ticket to see this?” And they looked at me, and said, “What do you mean?” I said, “Well, that’s what you’re putting on the stage. We can just look out the window and watch people do their ordinary life things. I don’t want to see that on the stage, I can [just] look out the window and watch life go by.” This was on Second Avenue in New York City, which was nice and active (laughing).

I think that sort of made the point that you can’t just put life on the stage as life exists. You have to do something to it, or with it, otherwise what’s the point? I can just look out the window. So, I hope that that was a lesson that stuck with them. It certainly stuck with me, because I never wanted to [choreograph] something that I could see in life that I did not have to pay for (laughs). If I’m going to pay a ticket price, I want to see something that will interest me, or excite me, or do something. I do not want to see life as it exists because I can do that any day anywhere. And that was not a popular view in the late 1960s.

TR I’ll bet (laughing). Actually, [I have] an earlier question that I had skipped over. You studied with a number of major figures in American modern dance.

GB At some point.

TR At the time, did it feel like a revolution?

GB I don’t think so.

I mean, I did go to classes. I needed to know what it was like, you know, to look like a Graham dancer. I just needed to know what it felt like in my own body. And it just didn’t suit my body at all. I just didn’t have the right setup in my hip joints to do what she was able to do. [Graham and] a lot of people built their careers on their own bodies.

TR Mm-hmm (affirmative).

GB But I needed to experiment, mostly to see if the choices I was making were the right choices for me. So, I did go to ballet classes, and I did go to Graham classes. The person that I liked best was José Limón. There was something very compassionate about him and very emotional. Whatever it was, his classes were just wonderful and his style of movement I liked.

So, that appealed to me a lot more. I did try other things, but I always went back to Nik, because there was the creative part of what he was doing, [which] was so interesting to me. And no, there was no one else who was offering creative work. I mean, the schools never had it. You know, they were mostly followers of a style. So, to be part of the Graham company, you had to learn the style of that, and you had to have the right body setup in order to achieve that style.

TR Mm-hmm (affirmative).

GB And you know, when you go to a class after a while, you know [what] suits your body, or [what] does not suit your body and so forth and so on. So, Nik had [used] a lot of different body types, but for the most part, we could all do certain things. And I noticed later, after I left in the 1970s, he was looking for a different kind of body. When I was there at the end of the 1940s and 1950s, he took what [dancers] he could get, and he got a lot of short, stubby people like me.

And (laughs), we didn’t have those long thin bodies like Carolyn Carlson. Once he had Carolyn Carlson, he looked for those long, extended bodies. But before that, he took what he could get, and he made stuff happen out of what he had, which was great for us.

TR Mm-hmm (affirmative).

GB Anyhow. I liked it. I look back on some things now, and I do see certain stylistic things, which I never saw for myself. I never saw them because there was always so much creativity around [what] we did, so many explorations. I never saw it as a specific quirk. Murray Louis had the quirks. He’s the one with the quirks (laughs). His “stylistic quirks” I call them. So, I think I may have mentioned this before to you that I didn’t like the fact that Murray’s personal quirks became synonymous with Nikolais’ work. That bothered me terribly, and it still does. We don’t see a lot of Nik’s work anymore, but there was a period when his work was being done a lot more, and people would associate [Murray’s work with Nik].

I saw this in students. They would imitate Nikolais, and I would say, “No, you’re not imitating Nikolais, you’re doing Murray Louis quirks” (laughs).

TR Mm-hmm (affirmative). Yeah, I wonder if that is because they merged toward the end of Nikolais’ life, when he was sick. They merged the two companies …

GB They did.

TR And Murray really was in charge.

GB I mean, they did it because it was financially too expensive to try to keep two separate companies going. There just was not enough opportunities for performances, and there was a lot of overlap with company people. So, they just merged. It was probably a good idea at the time, but artistically, I don’t think it was. Financially, it probably was better.

TR Mm-hmm (affirmative).

GB Artistically, I think, they were very different in their approach.

TR Mm-hmm (affirmative). Yeah. I’m going to pull up some photographs to show you. Just as a way to help …

GB Okay.

TR spark memories about some of those early pieces. While I’m doing that, are there other things about the early part of your career that you want to make sure we discuss?

GB I think what I was grateful for was the fact that the training was strongly based on what I will call principles of movement, [which] set up the possibility of using [those principles] to become a teacher. So that you’re not just imitating a series of movement styles or steps. You could invent your steps based on one of the principles of movement, which is what I

did a lot when I first started teaching. I realized [that when] I found my old notebooks.

I would actually list [ideas, such as], “Okay, this week, we’re going to work on spatial ideas.” And [we would] invent materials about different kinds of spatial ideas. One class was about enveloping large spaces or enclosing spaces, or, you know, reaching out as far as you can go. There were so many subjects within that, and it made it possible to teach over a long period of time without being repetitive, because you could find all sorts of ways to do that. It was great.

I mean, [if] you were a student in those early days when I was still really thinking about those things, I would invent the material right there in the classroom based on whatever principle, or whatever idea, I had in my head that day. And that was very creative for me as a teacher, you know, you could take the same idea and just do lots of different movements on it.

So, the teaching experience was as creative for me as it was for whatever the student got from it. That was, I think, one of the best things I ever got from Nik. It was a way of teaching that was not just repetitive, or just making up a series of combinations just for the sake of a new experience, but it was based on something. That always interested me.

TR Right. There was a conceptual framework that was endless.

GB That’s a good way of putting it. Yeah, exactly.

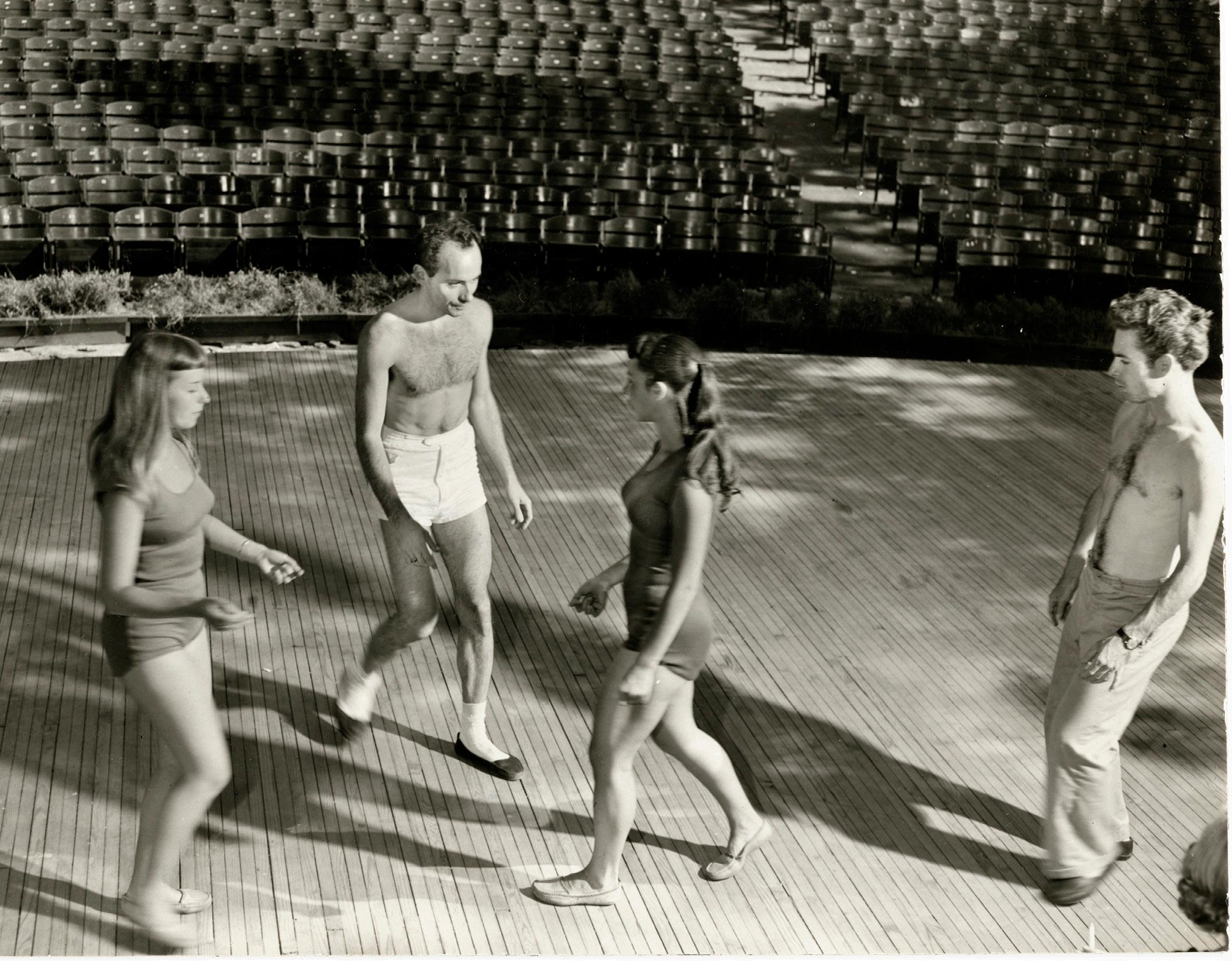

TR Yeah. Mm-hmm (affirmative). So, this first [image] I had never seen before.

GB Oh, that’s with Don Redlich.

TR Oh, okay. I couldn’t tell.

GB It’s Don.

TR Mm-hmm (affirmative). So, this was one of his pieces?

GB That was later.

TR Mm-hmm (affirmative).

GB That was in, when did I meet Don? I think it was like the mid-1960s. Yeah, I [had] left the [Nikolais] company. They started to tour a lot, and that was not what was in my playbook. By that time, I was already in my 30s, and my husband and I decided to adopt [our son,] Peter. And once you make a commitment you are going to have a family, you didn’t have the freedom to go romping around the world. And that was a choice I made. And you know, after a while the touring is a bore and a half. It’s awful. You’re packing, unpacking, and you are in a new place all the time. You have a new stage and you have to go through the same lighting stuff. It is terrible.

Gladys Bailin and Kelly Holt.

The Gladys Bailin Papers, Ohio University Libraries, ca. 1960s.

GB People think it’s great. [But] you don’t have a lot of free time, at least not with Nik. And you know, you think you are going to travel and go to Europe and do all that, and you don’t see anything. You’re just in the theater all the time, or you’re nursing your body in the bathtub (laughs) because it hurts (laughs), or you have a sore back, or you have a sore knee (laughs), or you have a terrible splinter (laughs). You know, it’s not glamorous (laughs).

TR (laughs)

GB So, I didn’t want to travel anymore, because it wasn’t glamorous, and you had to be away for long periods of time. But that [image] is with Don. That was one of the early days (laughs). He was one of those silly dancers, one of the funny silly ones.

TR Mm-hmm (affirmative).

GB It was actually a pleasure to work with Don. Oh my God that [photo] is Kelly Holt. Yeah. Kelly was my colleague at NYU. He came from a totally different technique, Eric Hawkins, which I thought was the most boring thing I’d ever seen in my life. Kelly trained with Hawkins. And somehow, we got to be friends, [but] we were from two different worlds. I made a piece with him and me because he was a very big guy, and I liked that. I liked that difference, and he was very nice.

So that’s Kelly Holt. I don’t know what happened to him now. He lived in Cleveland,

Ohio for a while (laughs). He was older than I was (laughs). It was interesting to work with him because he came from such a totally different background.

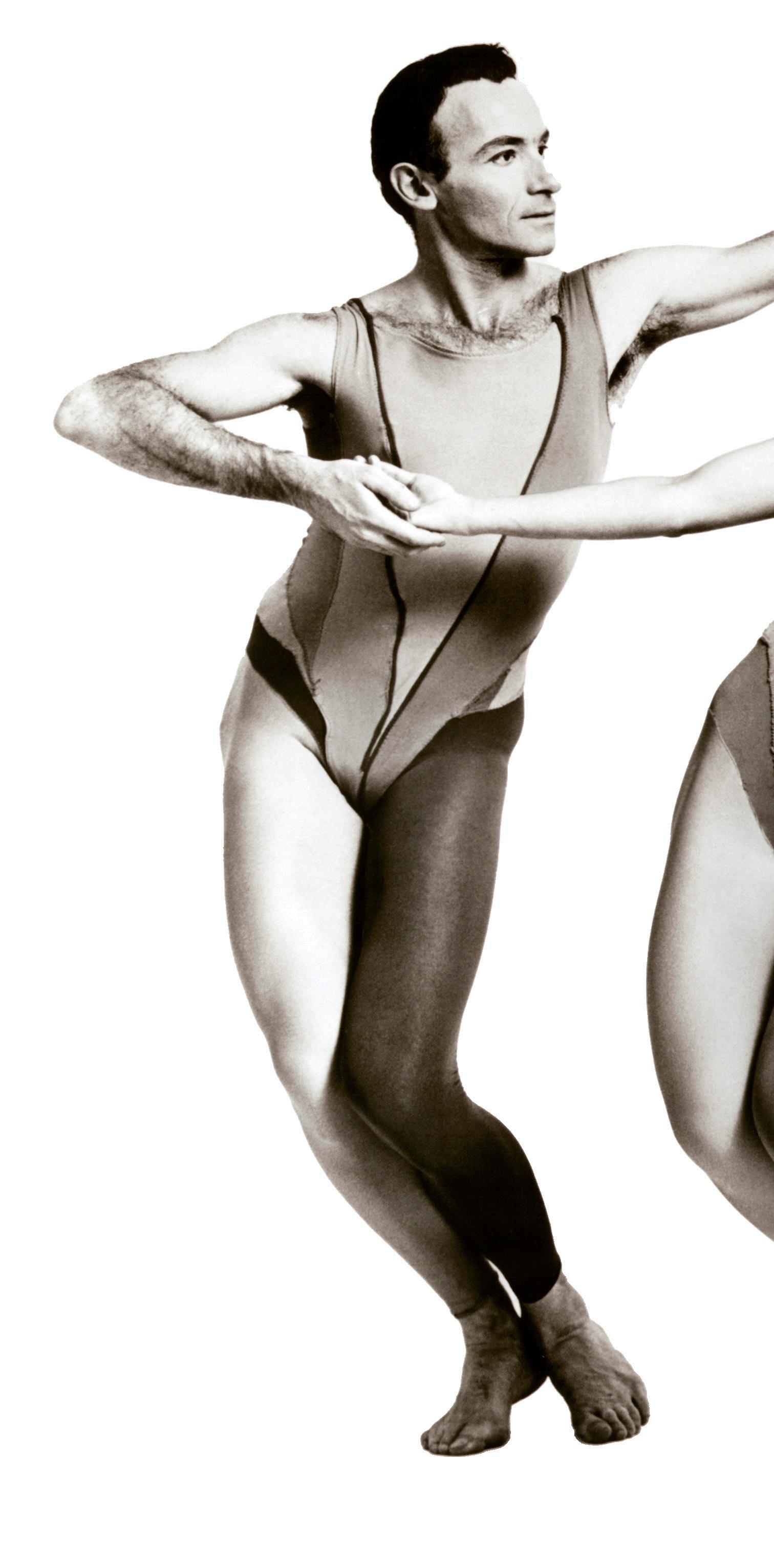

Oh, that [photo] is Murray Louis and me in “Odyssey.” Murray made some nice work.

TR That was one of Murray’s pieces?

GB Yeah. Oh my God. That [image] was before my time. That is very early. I think it’s either Anna Sokolow, or one of those early modern dancers who did something like “Peasant in the Streets,” or something like “Tess,” [or] you know “Tenements” or something like that. I think that’s from that period.

It’s very early. Maybe the 1930s. Maybe even the early 1940s.

TR So that’s not you in the middle there? I couldn’t tell. It kind of looks like a very young you, but (laughs) I wasn’t sure.

GB You know, I think that is me. [And] that’s Phyllis [Lamhut]. Oh, yeah, this is probably something reproduced. Nik would sometimes do that. He would bring somebody in.

TR Like a reconstruction?

GB That was in the early days.

TR Uh-huh (affirmative).

GB Oh, I love that photograph. I have that on my desk. That was a very early group of people who were there [at the Playhouse]. There’s Murray. You see him? And this is Bill Frank.

TR Mm-hmm (affirmative).

GB This guy here was Floyd. He didn’t hang out much. This is my friend, Phyllis [Lamhut]. We’re still friends. That’s my friend, Debbie. She was a pianist and used to accompany us. That was Billy [Siegenfeld] or somebody like that. I don’t remember, and that was Ruth Grauert. She became the stage manager [for the Nikolais Dance Theater]. That was such a great little group. That was probably in 1950 or 1951 (laughs).

TR And then, is this “Kaleidoscope?”

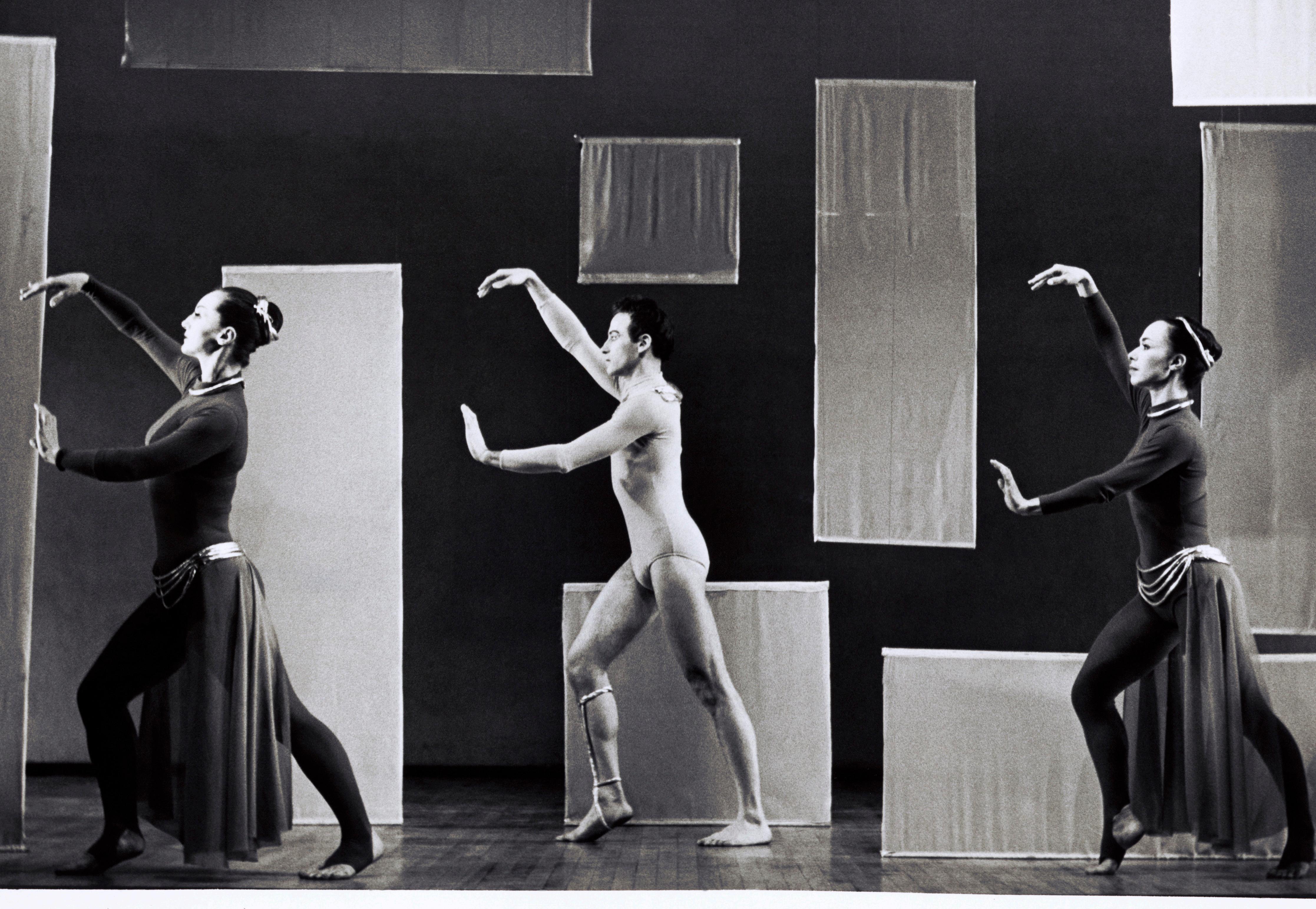

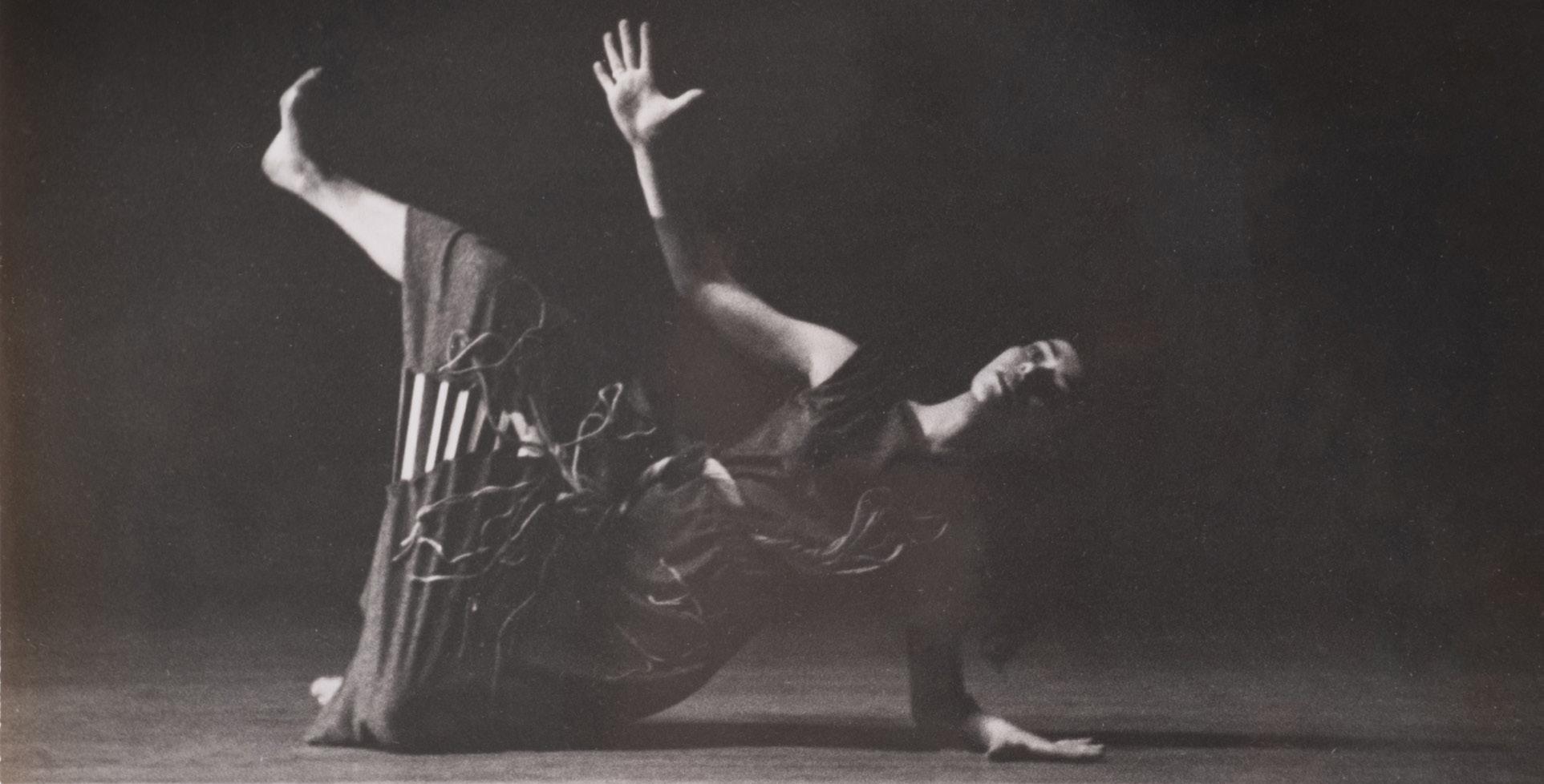

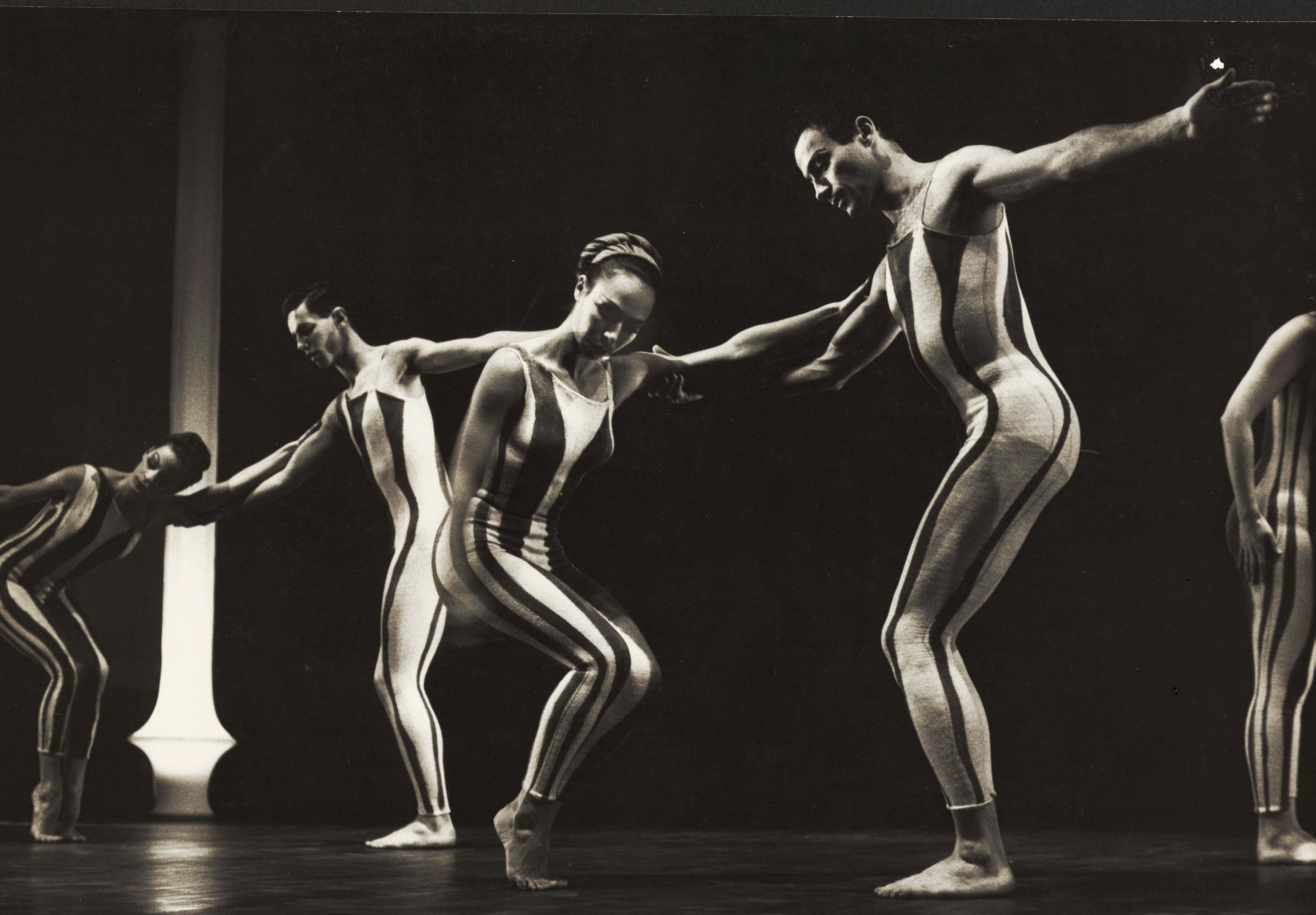

GB That is so beautiful. [That image] is one of my favorite pictures. Yeah, that’s called “Pole.” It’s from “Kaleidoscope.” It was the second piece. “Kaleidoscope” was made up of eight pieces. They all had a prop, and this one was called “Pole.”

TR Mm-hmm (affirmative).

“Heritage of Cain,” Gladys Bailin (center front) and Phyllis Lamhut (left front).

Choreography by Alwin Nikolais. Nikolais & Louis Dance Collection, Ohio University Libraries, premiered April 30, 1951.

GB And the costumes. Even the makeup. You can’t tell on here, [but] we had our one side [painted] green, [and] the other side was blue. You can’t see the color on that, but it had to do with the costume being very severe, too. It was painted on us.

We didn’t have that wonderful fabric [that] we have today. We used to call this lizard skin because it was puckery. And it had elastic in the back, so it would stretch, and it would somehow come back. That was always the problem. You couldn’t find fabrics that wouldn’t bag out. You know, you bend your knee and then suddenly you’ve got a poof there (laughs). You had to have something that would come back [to its original shape], and that was [the fabric] they used to make for bathing suits, or something like that.

It was cotton. And then we had to stand there, and Nik would paint it on us (laughs).

TR Oh my God (laughs).

GB He would paint these abstract lines (laughs). I spent a lot of time in the basement in that costume room.

That’s an early one. Oh my God. That’s Beverly [Blossom] on the left.

TR Uh-Huh, (affirmative) Beverly Blossom.

GB That’s Murray.

“Kaleidoscope,”

TR Mm-hmm (affirmative).

GB You know, I look at this now, and I begin to see [that] even the stage design is kind of abstract. Rectangles and squares. I don’t remember the name of that piece, but I’m looking at the costume. I can’t remember what it was called. It sort of strikes a memory but not a great one (laughs).

TR And here’s one that I’m assuming was one ...

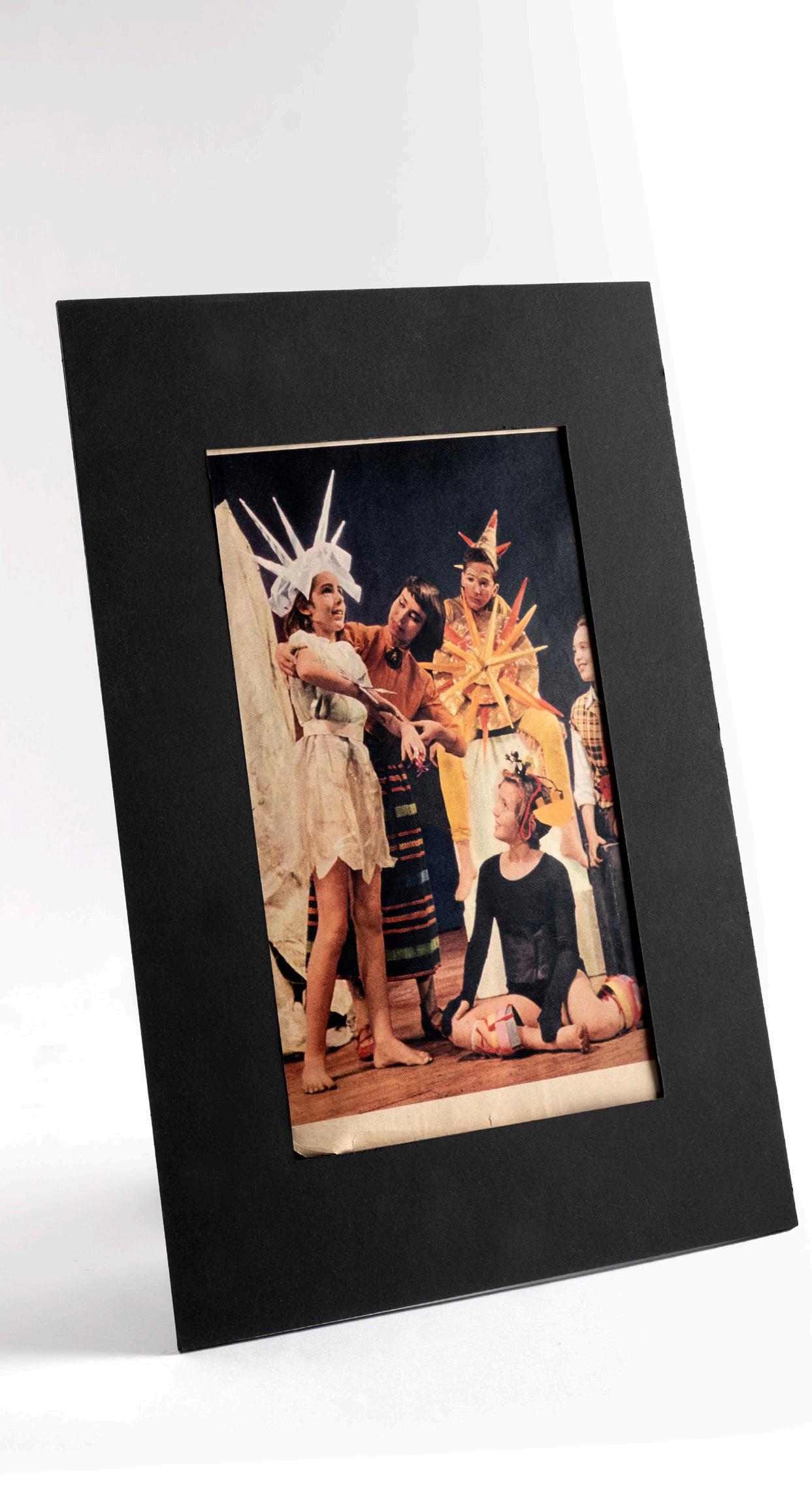

GB Oh, that’s one of the children’s pieces. Yes, that was “Sokar and the Crocodile.” And it took place in Egypt (laughs). I think those were painted pillars. Yes, that was “Sokar and the Crocodile” (laughs).

TR Mm-hmm. (affirmative)

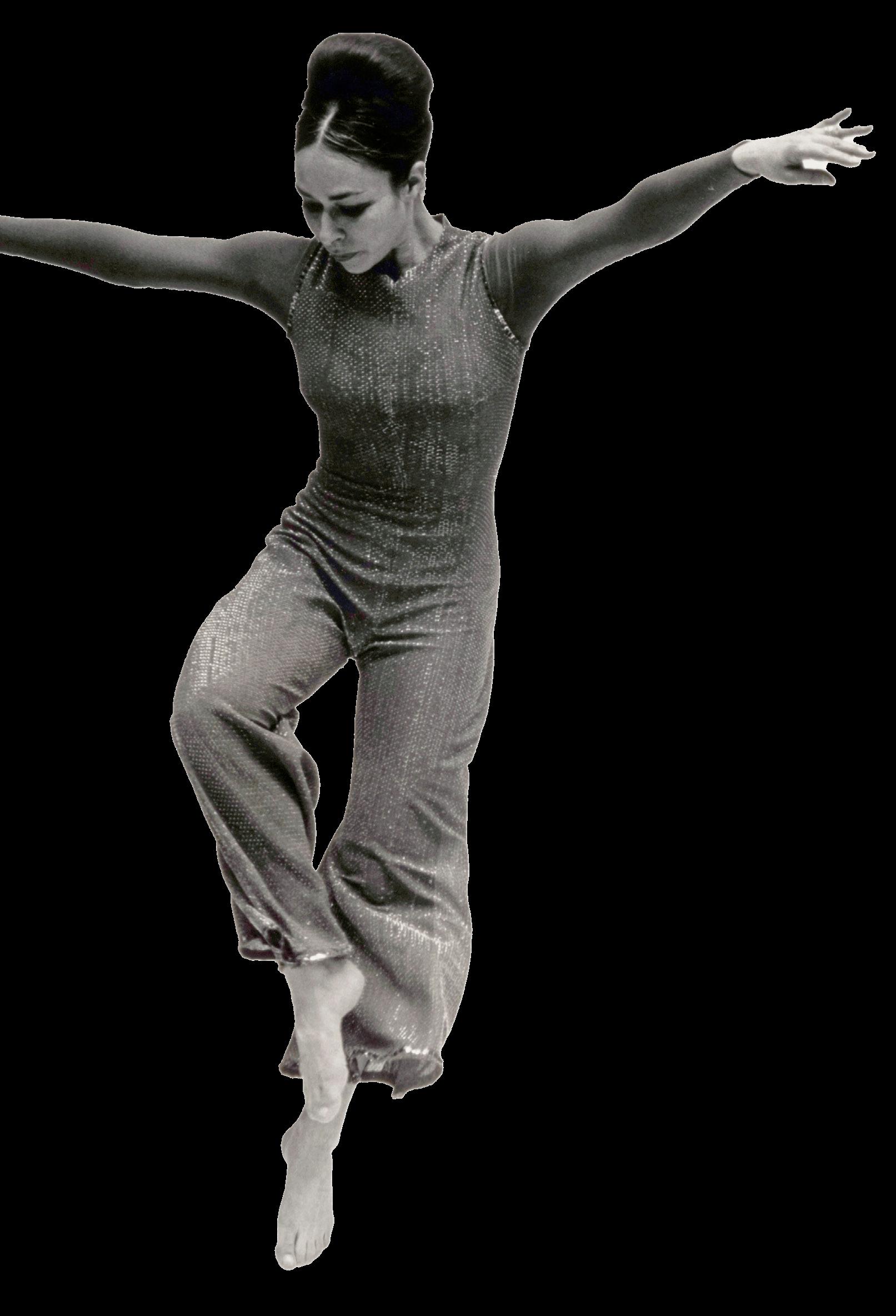

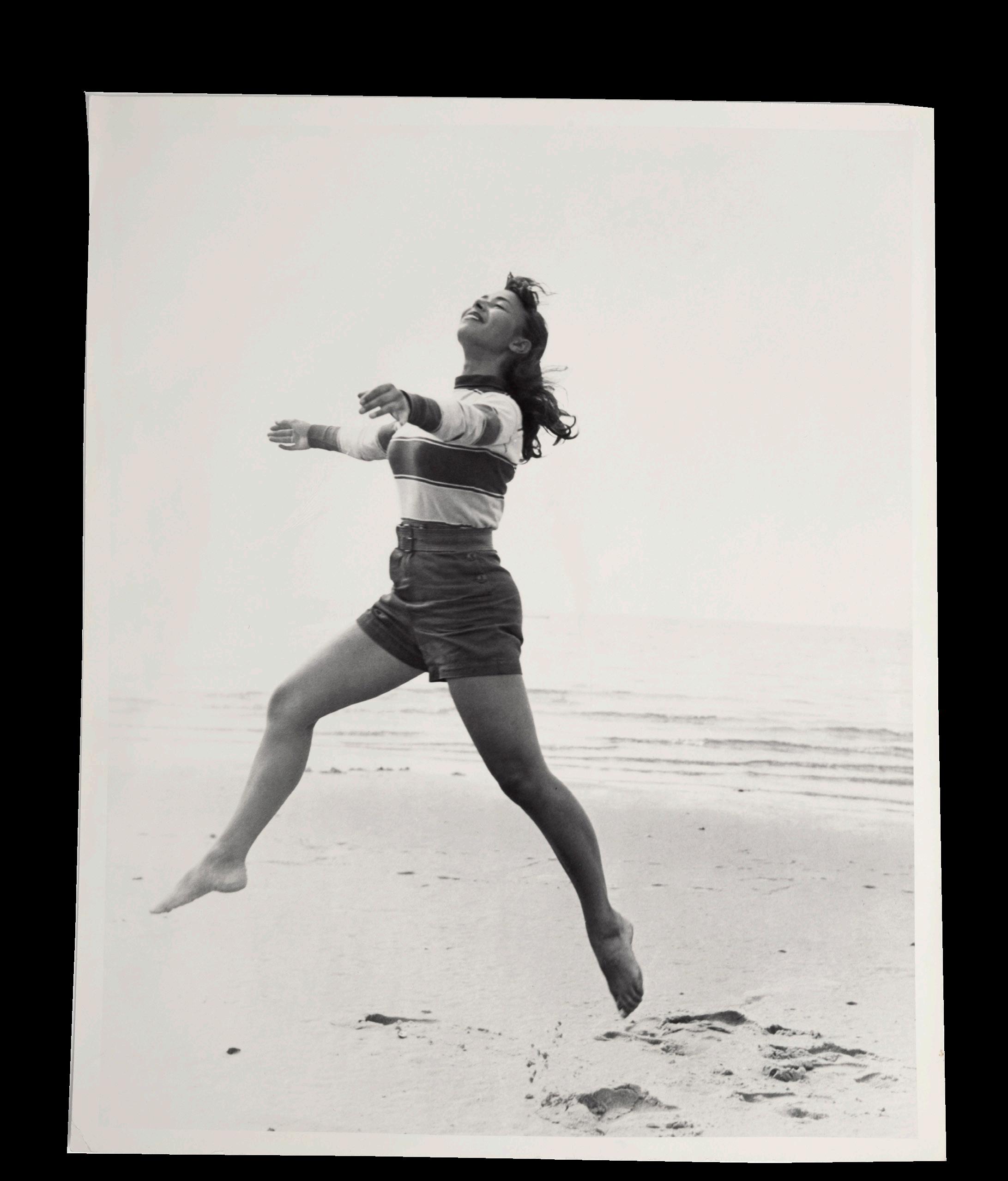

GB That was actually a very nice children’s piece. Oh my God. That was a solo, and I think it was called, “Creech.”

TR Mm-hmm (affirmative).

GB And it was a creature. I don’t know, it was an unnamed [creature]. But that’s what it was (laughs). One of my early solos.

TR And that’s such a beautiful photo of you.

GB (Laughs). I think that’s what it was called. I remember seeing something once, some title, and [I think it was] “Creech” (laughs).

TR I just thought of another image that I want to pull up.

GB Oh, that was another one of the children’s pieces. I remember my mother made those [costumes]. They were supposed to be porcelain figurines on a mantelpiece. What was the name of that one? Oh, God, I hated the costumes.

TR “The Shepherdess and the Chimney Sweep.”

GB Do you remember something that they used to have on [kitchen] tables called oilcloth? That’s what they were made of. So, it would look like porcelain. It was shiny outside, and it didn’t breathe at all. It was horrible to wear, but it looked great from the stage, because it did look like porcelain. We did this [dance] on what was built [to look] like a mantelpiece, [which was built] on a six-foot by eight-foot board, and we did that whole thing [dancing on it]. It was just one of those lovely little children’s things.

TR Mm-hmm (affirmative).

GB But it had a set piece, and I think the music was Kodály. A real piece of music.

That was played on a phonograph (laughs). We didn’t have tape at that time. Can you imagine? And you couldn’t jump too much on stage, because then the phonograph needle [would] jump (laughs), and it would skip. Oh, that was

“Sokar and the Crocodile,” Gladys Bailin, choreography by Alwin Nikolais.

Photography by David Berlin. Nikolais & Louis Dance Collection, Ohio University Libraries, premiered Dec. 28, 1950.

the worst part: dancing to phonograph records (laughs). That goes back a while (laughs).

Oh, that is the first dance of “Kaleidoscope,” called “Discs” (laughs). That was the prop. A piece of metal tied to our foot. We could stand up on it, but it would clank, and it made noise, and it was startling. But it has an interesting look when you see it.

TR Mm-hmm (affirmative).

GB But you had to find your own way to strap it on, so it wouldn’t loosen, and it was a big deal.

TR (laughs)

GB [Nik] had this idea that you could stomp with one foot and stand up on it, spin on it and do all sorts of tricks. But you had to tie it very well (laughs). And I think, he painted it so that the bottoms had a different color from the top. Yes, this was a trio, which was all part of “Kaleidoscope.”

Another section of it had these straps that were attached to the grid holding up the curtains and everything else. And they were actual straps. We could lean, and we could throw ourselves off center because of them (laughs). It was called “Straps.”

TR I love it.

GB Yeah, they all had a different prop. It was sort of interesting. So, you found these old photos?

TR Mm-hmm (affirmative). Yeah, I’ve gotten them from the [Libraries’] archives over the years.

GB Uh, huh.

TR I love this one with the bird.

GB That was another one of the children’s things. I don’t remember who played the bird. Is that Phyllis [Lamhut] down at the bottom? I think Murray and I were trying to catch the bird? No, it looks like someone [else]. Yeah, that was one of the children’s things too.

TR Mm-hmm (affirmative).

All right, well that’s all the questions that I have.

GB Okay. Well, you [have] to love those nice old [photographs].

TR Yeah.

GB And it was a good mix of the children’s [work] and the concert work.

TR Mm-hmm (affirmative).

GB It was interesting when you think back that the next group of students, who came through [the Playhouse] inherited the children’s works. Because those of us who were in the original company sort of graduated to the concert works. So, the young ones coming up could now do the children’s things. It was kind of wonderful. It’s like the old apprentice system, in a way.

TR Mm-hmm (affirmative).

GB You know, [when] they would take it on, [new students] would have a performing experience with the children’s works and so forth and so on. And then [when] we left, they would graduate up. There was a tier system, in a way (laughs). Like you do your apprenticeship and then you go on.

TR Right.

GB [Nik] made it work.

TR Yeah, he was so versatile. And he had so many different aspects to the work that he did, you know?

GB He did. He could manage the thing. He was a musician. He was a choreographer. He

“Kaleidoscope,” choreography by Alwin Nikolais. Nikolais & Louis Dance Collection, Ohio University Libraries, premiered May 27, 1953.

imagined stories. I mean, it was like working with a genius.

GB There are very few real geniuses around. And I feel so fortunate, in a way, that I had an opportunity to work with somebody who was so enormously creative in so many ways. To have just been a part of his working life was remarkable.

TR Mm-hmm (affirmative).

GB Plus, the fact that he was also a very good cook. One of the nice things that he did with the young company after a Friday night rehearsal, or something like that, he would say, “Come on over to my place.”

TR Mm-hmm (affirmative).

GB He lived in a loft, [which was] the first loft I ever saw. That was very unusual back in the 1950s. And he would just [make something to eat with] whatever groceries he had. He was a very good cook. He just made a lot of it, and he would invite all the young people over, and we would sit around and laugh, and eat and jitterbug (laughs).

TR (laughs)

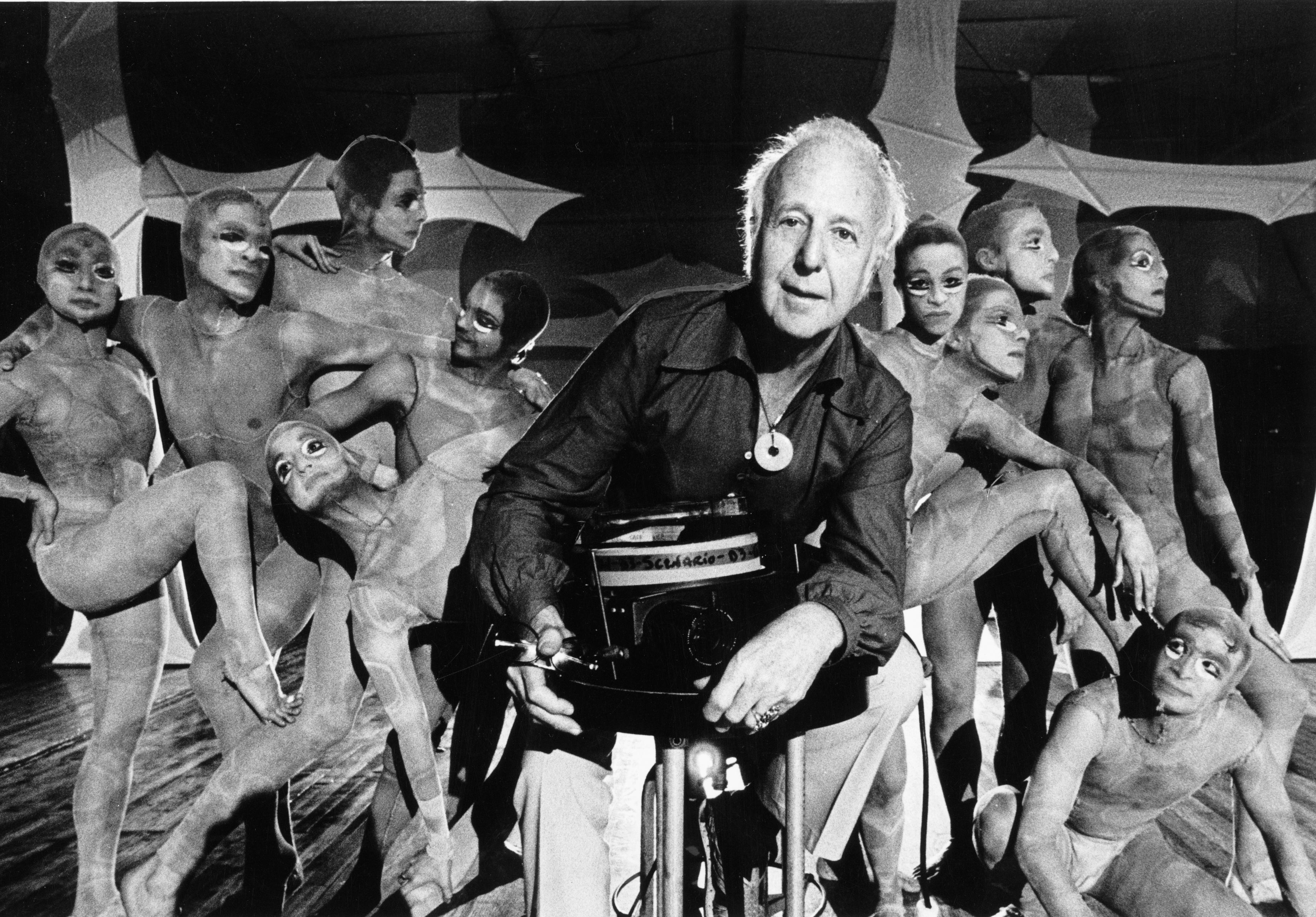

Alwin Nikolais. Nikolais & Louis Dance Collection, Ohio University Libraries.

GB And [we] put on those wonderful records that we liked. And then had a holiday and danced (laughs).

TR I’m sure it was like a family, right? It was like you were part of a family, being in a group like that.

GB It was. It became that. And he made it all happen because he would feed us, too (laughs). He was like a mother and a father to everybody. It was great. Murray [Louis] was always funny, you know? When Murray came along, he always had a lot of commentary that was hilariously funny.

TR (laughs)

GB [Murray] was a very good writer. [Have] you read some of his things?

TR Yeah, he is very [good]. Very witty.

GB Yeah, he’s a good writer. I’m so glad he wrote those books when he did.

TR Mm-hmm (affirmative).

GB Wow, we covered a lot of territory here (laughs).

TR It was perfect (laughs).

October 29, 2020

AW We are talking with two people. Would you like to introduce yourselves?

GB I’m Gladys Bailin.

TH And I’m Teresa Holland.

Gladys, hi. You came to Ohio University in 1972?

GB Correct.

TH Can you talk about what brought you to Ohio University, and your decision to join the School of Dance?

GB [I] got a call from Shirley Wimmer out of the blue. I didn’t even know how she [knew to] contact me, but I found out the dance world

is pretty small. Shirley [had] contacted Jean Erdman, who was a dancer and the first director of the School of Dance at Tisch. [Jean] actually started the school at Tisch at NYU. So, Jean knew me, and Shirley talked to Jean when she was looking for faculty, [and] Jean told Shirley, “Call Gladys.” So, I talked with Shirley on the phone, and I liked her enormously.

She was a very good phone person by the way (laughs). She had a lovely manner, and it was very inviting and without too much push I said I would come out and visit. I can’t remember what time of year she called me, but I think we came out in March at some point. I wanted [my spouse], Murray, to be able to come and [our son], Peter. So, if there was any possibility

that we would [need to] leave our apartment in New York, which was a horrendous idea to give up a [NYC] apartment, the whole family had to be sure that this was going to be a good fit.

Well, we did come out. We flew to Columbus, rented a car and [drove to Athens]. It was a gray day like [it is] today. It had snowed a little bit prior to this, [but] this is March [weather] now. So, there were traces of snow along the side [of the road], and it was cold, and it wasn’t particularly pretty. I thought the drive was forever, and I said, “Where is this place? Athens is so far from a city.” The landscape did get nicer, but there was [just] not a lot there, you know, very few leaves left, but there were still green hills and stuff.

Eventually, we arrived at Pat Welling’s house, who was going to be the host. Pat was the one who put this all together. I’d met Pat the previous summer at a workshop that I was teaching in Detroit. Pat, [who had] taken the workshop, told Shirley, “You know, call Gladys. Her workshop was great, and she may be a good fit.”

So, we did come, and Pat was lovely. We left [our son] Peter with Pat and her family at that time. All her kids were older than Peter. They were teenagers. But [all] Peter saw (laughs) [was] that they had a dog, and that’s all he cared about (laughs). He wanted a dog. He’d been talking about having a dog forever. And I

kept saying, “No, we can’t have a dog in the city, and we can’t have it in the apartment.” But I remember saying, “If we ever moved to a house, you could have a dog.” So, Murray [went] looking at real estate [with] Peter, [who] said, “Oh, we got to get a house, so we can have a dog” (laughs). I mean, he’s nine years old, and he’s fixated on that.

So that was sort of the setup for the whole thing. It turned out that I did meet with Henry Lin, [dean of the College of Fine Arts]. I think Shirley Wimmer set up the meeting with Henry. It was a weekend, so there were no real classes [in session], but Shirley had made sure that there were enough students around to interview me. So, I had the interview with Henry, and I had an interview with the students, and I saw the space, and it was kind of yucky in a way.

This is pre-Putnam Hall. [Instead], we had studios above Walgreens [in uptown Athens], which is now a Chinese restaurant. That building has a little side entrance that leads to a steep flight [of stairs before reaching] two studios and a little office. And that’s where I went. The big studio was quite nice. The small studio was pretty small, and [there was only] one bathroom for everybody. It was primitive, I would say (laughs), but it reminded me of New York City (laughs), and some of the places where I had taken class.

So, [the space] didn’t feel foreign at all. And Shirley was just a charmer. The students were just marvelous. We had one class [that] I taught. There were enough students around [to] interview me, and we sat around and chatted for a long time. [We] then spent the evening at Pat’s house, and then we went home on Sunday evening. During the week, Shirley called me.

And she said, “You have the job if you want it.” And I said, “I’ll call you back.” I talked to my husband, [and my son,] Peter, couldn’t wait. He said, “Yeah, let’s go because we can have a dog.” That’s all he talked about (laughs). He didn’t care about anything else. I said, “Well, I have to find out what the salary is going to be” (laughs). It turned out it was a pretty yucky salary, but I’d already interviewed at UCLA, and I didn’t like it. I didn’t like the atmosphere up there. And I also knew that the cost of living was going to be a lot cheaper living here [in Athens] than in Los Angeles. The salary was competitive, and I figured we could live on that [salary] here, [but we] couldn’t live on that in LA.

There was something about this place that it just seemed like an okay idea. I was curious. I needed to talk to my husband because he was without a job, but he was doing a lot of freelance work at that time. And so, it didn’t seem to matter as much to him about the steadiness. He wasn’t looking for a steady job.

[So,] we just came out [to Athens] and enjoyed the weekend a lot. And my husband said, “Let’s give it a try. We’ll give it three years.”

TH Mm-hmm (affirmative).

GB “If it doesn’t work out in three years, we’ll move on.” I said, “But we can’t go back to that apartment in New York because we [would have] given it up.” Well, my husband always took this very positive view, and said, “Don’t worry about it. You’ll never starve” (laughs). And I said, “I’m not worried about starving” (laughs). But he always took that view: “We’ll work it out.” And this [did] turn out to be a pretty good place.

One of the things that I rather liked were the students, who didn’t seem jaded. They seemed so open and eager. They were ready to just swallow up what I had to give them. It wasn’t that feeling, “Oh, I’ve heard this before,” or “I’ve seen it before,” or “I’ve done that.” There was a freshness about them. That was so nice.

And I thought, “Wow, you know, they’ll do anything I ask [of] them” (laughs). Not that I was asking for anything extraordinary, but it was the openness that attracted me. And the fact that Shirley was so willing to let me do my thing. She didn’t have any specifics or ideas of what she expected. [Instead,] she said, “I bring you [here] because you bring what you do.”

And that was very freeing for me. And I said, “Okay.”

I looked at the setup, and I said, “We have to change the curriculum” (laughs). If [dance] was going to be a major, it had to have a little more substance to it. [At that point, the curriculum] was too scattered.

So, I said, “Well, you know, they have to have a technique class every day, and they need to have this, and they need to have that.” And Shirley was willing to adjust the curriculum. There was just such a willingness to establish something firm. So, I said, “Yeah, let’s just go ahead and do it.”

[Shirley] had a pretty a good relationship with Henry Lin, who was the dean [of the College of Fine Arts] at the time. And that was fortunate because Henry was fussy. If Henry liked you, he would let you have money for your budget. If he didn’t like you, he would [with]hold money.

TH Hmm.

GB So, it was very important that Henry liked Shirley. She wanted me to meet Henry, and I got along with Henry also. So that was very helpful, but Henry was very controlling about the budget.

The budgets were very, very small. I didn’t know this [at the time]. I was wondering why Shirley was always going over [to Henry Lin’s

office]. [I learned] she’d make pleas for certain things. “I need money for a guest. I need money for this. I need…” and he would dole it out. I thought, “Oh dear, this is awful.” I mean, it is a way to control, and that happened for a while. Then at some point, I don’t know if I ever did it directly, I said, “We just have to have a bigger budget, so we can control it. [We should] not have to go and beg for it.” [Our relationship] was a very student-teacher or father-child kind of thing (laughs).

Eventually, we did get a budget, which was not very big, but at least we could control [it] ourselves. We didn’t have to go and make a case for every little thing we wanted to buy, or every person we wanted to bring in.

Anyhow, I think what kept me here, because certainly the facilities were not great, was really the students, and the people I worked with. They were just nice, open, willing people, and they were just drinking up what I had to bring. I was still fresh and young, and I had a lot of enthusiasm. [My work] was even fresh to me. So, it was a good match [and] worked out very well. It was during that time that we were able to move from the third floor of the [Walgreens] building to Putnam.

TH Hmm.

GB [Putnam] had to go through renovations, but it was so nice to suddenly have the gymnasium, which was a huge space. [In the Walgreens’

studios,] we really didn’t have a big enough space. You made two or three leaps, and you were across the room or [running] into the window (laughs). So, the gymnasium was great.

[For Putnam’s] third-floor studios, it took a while to get the sprung floors. But we managed, and it was nice having our building [shared] with the little daycare center. The students would peek in and watch what was going on. And a lot of the [students] would sit and watch those little [daycare children].

Pat [Welling] was also in charge of the [student] teaching program at the time. Pat was wonderful with little children. She went out to the [public] schools, I think, [when she headed the] teaching program, which was pretty good ...

TH Mm-hmm (affirmative).

GB at that time. And she took a lot of [students] out to [the public] schools to teach different [classroom] levels. They don’t do this anymore. I don’t even know if the schools [would] have it. Anyhow, all the [dance] students had to take the pedagogy classes, so that they could have a vocabulary in which to teach, which they could then adapt to older people as well. So, I think the curriculum was really good at that particular time. And lots of students came to dance. I mean, the 1970s were good.

I think one of the big motivators was the [Ohio] Arts Council. There was money for that. We used to have wonderful things come to the Performing Arts Series because there was money that was paid for through government [funding]. And it was a wonderful time for dance companies. I mean, they’re suffering terribly now. [With the COVID-19 pandemic,] nobody goes to the theater.

But dance began to flourish in the 1970s, because there were outlets for performances. There was subsidy money for performances, and there was money for teaching and getting out. And there was this great [big] push out into the schools. It was a really good time for dance.

[At that time] I think dance became one of the arts that was respected, along with music, [which] always had that because it is one of the oldest [arts]. Theater also became part of a

school’s [curriculum], music was always there, and now movement classes became part [of it]. And it wasn’t just a physical education class, [although] even the physical ed teachers were taking dance classes, so that they could [teach] other things.

The 1970s were good. It was probably the best [overall] time for dance, [and] it started to flourish. Companies started to take shape, and they could get bookings, and there were schools that would hire dance companies to perform.

The 1980s were still not too bad [either], but it started to dry up a little bit more. Now it’s completely dead. When you look back, [you can] see how this whole thing has petered off. The arts are [just] no longer important because they are not important to the government. It doesn’t seem to be important to our president at all. I mean, [Donald Trump] doesn’t even bring in artists to the White House. At least some of the previous presidents did that. They wanted to encourage American art. This one has nothing to do with art. He’s just [not] artistic.

TH As one of two or three dance professors under Shirley Wimmer, the former director of the School of Dance, what was your strongest asset you were able to offer to the dance program and the curriculum?

GB I think one of the things that I felt very strongly about was the fact that there would always be creative work. I had been able to see other [dance] programs [across the nation] and there were lots and lots of programs that turned out good movers, you know, good dancers, technical movers. And I thought if OHIO’s School [of Dance] could focus on the creative aspect of it, we would make a niche for ourselves. So that would become unique to this particular school.

[We] would make [the] Ohio University School of Dance stand out among the hundreds of other ones all over the country [by] pushing out creative work. That was the thing I really wanted to have happen.

If we could make a name for ourselves that way, it would attract certain kinds of students who wanted to have their own creative work encouraged in some way. There were tons of technical dancers. I mean, they were everywhere, and that was not unique. The fact that we had creative work as part of the curriculum rather than just an extracurricular activity, I thought, was something. It was tricky because many of the students who we were getting [into the program] didn’t have any background for that.

You had to sort of encourage it and tell them [that] there is a whole new way to look at things. It doesn’t mean that you’re going be a choreographer, but you are going to tap

something in yourself that is going to open up other doors, so that it’s the idea of thinking creatively. It’s not always what you necessarily accomplish, but if you become a creative thinker, you can use this in every aspect of your life and use it in other areas as well.

So, I pushed that a lot, and I was very happy that Shirley went along with it because it did become a part of the [dance] curriculum. [Choreography] was not a choice. It wasn’t something you would select to do, [but rather] you did it for four years, which was unusual.

At some later point in my life, I became an evaluator of other schools, and I visited schools pretty much all over the country. And [found] what we were doing [at Ohio University] was very unique [compared to other schools]. Most of their curricular choreography, or what I like to call creative work, [consisted of] two or three courses, or at the most four. It was really incredible. And then they expected the students to turn out a [choreographic] product at the end, but [students] didn’t have any experience in how to do it.

So, the fact that we [at OHIO] made [choreography part of the curriculum starting] from freshman year through improvisation, [which was] less formalized, and becoming more formalized [each additional year of the program] was one of the unique aspects of [our] school. And it did attract certain kinds

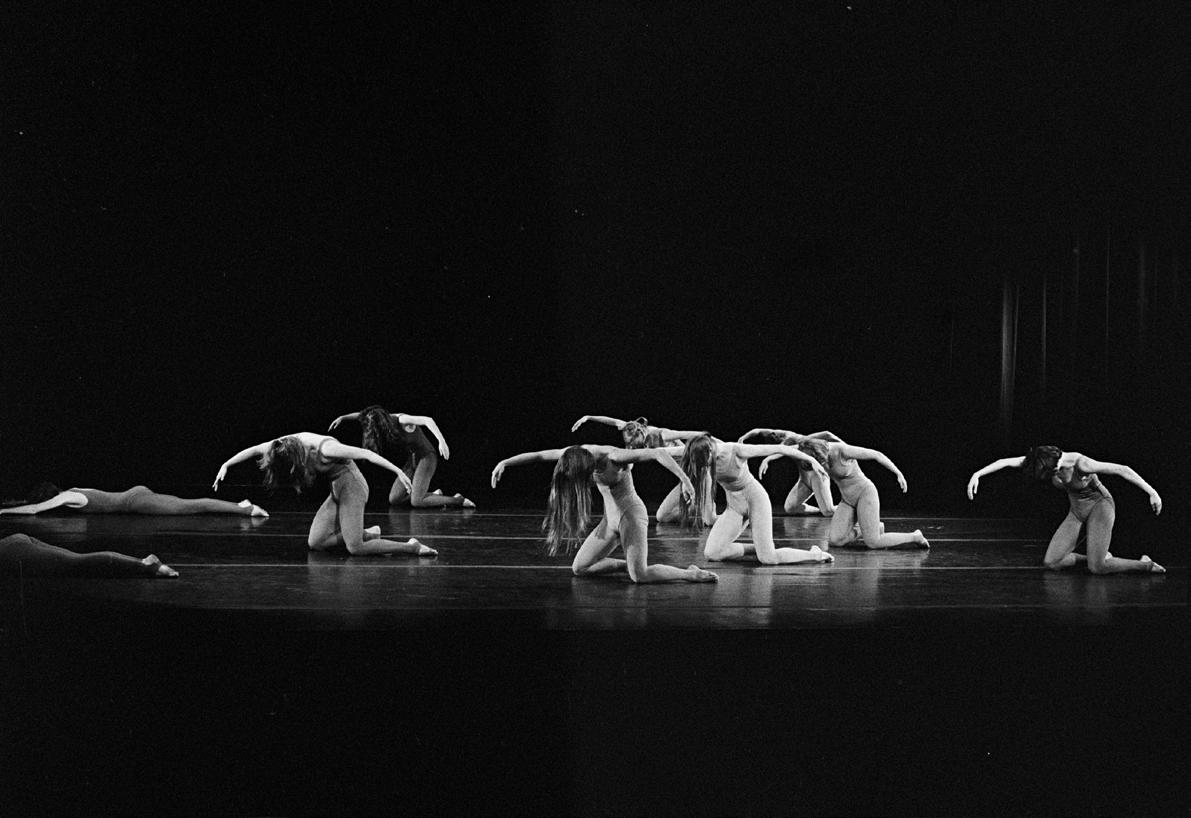

A student dancer performing.

University Photographer Archive, Ohio University Libraries, 1978.

of students who were interested in their own [personal] expression and [whose work] would be accepted and shown, not just put aside.

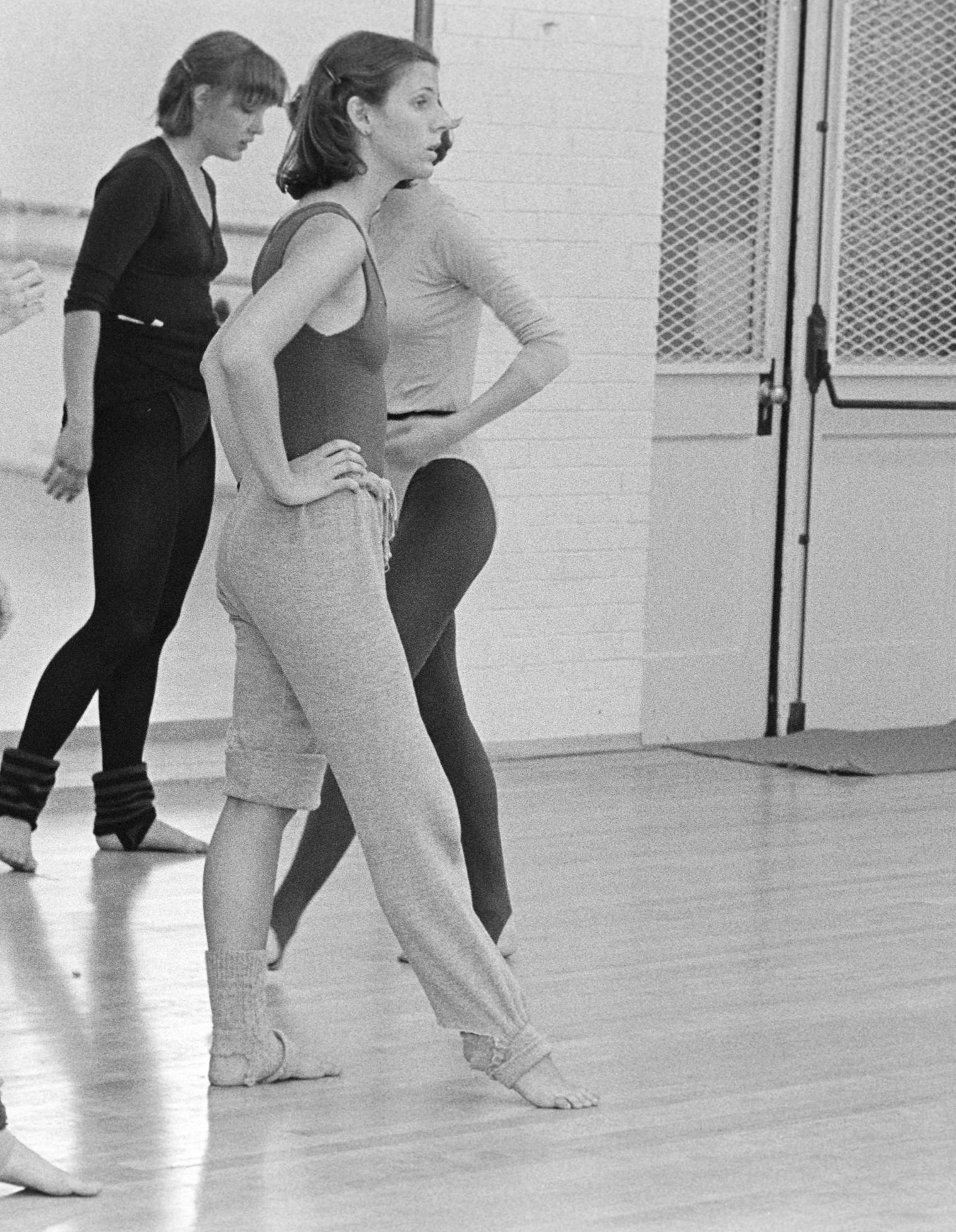

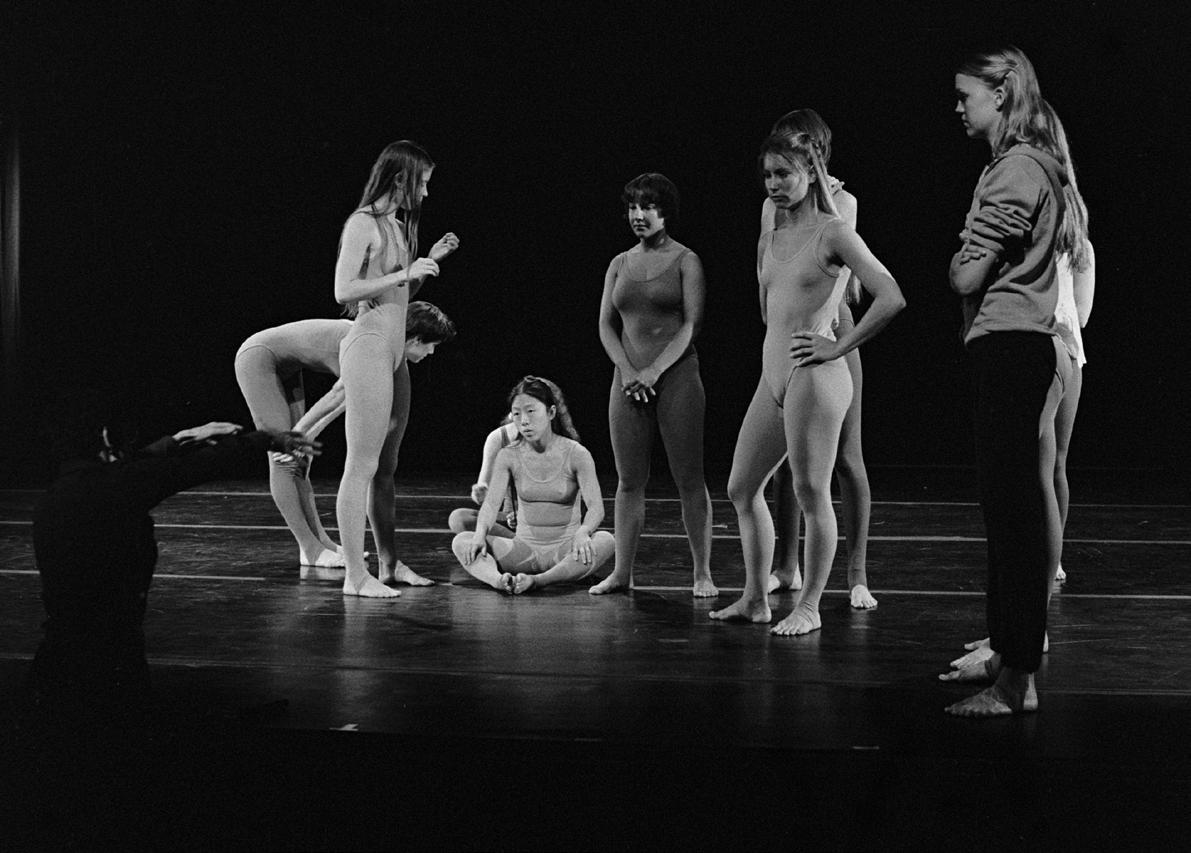

One of the things that I brought [to the program that] was not here before were the [Friday] workshops. That was something I brought from NYU that Jean Erdman picked up. [The workshop] was an opportunity for [students] to show what they were doing in class to other people. That’s really where it started. And I thought that was such a good idea, because even those who were shy, [who] got up [and performed] for classmates, were learning how to perform. Students were learning how to make their work visible to somebody else. They weren’t just keeping it to oneself or being shy about it. [As] performing artists [you have] to get it out. And if they didn’t have exposure to that, it became too precious, and it became too frightening. But if you performed on a regular basis, it was less frightening.

So, the Friday workshops became what students were doing in their composition classes. It also became very important for the other teachers to see what [students] were doing.

TH Mm-hmm (affirmative).

GB And it was interesting [to hear] students say, “Oh yeah, we did that when we were freshmen,

and now we’ve graduated, and we’re doing this.” And also, for the freshmen students, they could see where they could go when they would see the work of the [upper-class] students [and think], “My God, I could take this little study and develop it, and it could become something else.” So, I think the workshops were so important. And that Friday 3:00 to 5:00 p.m. [designated time] for the workshop became sacred. We would not do anything to interrupt that particular flow of the training.