ALEC NAKTIN PORTFOLIO

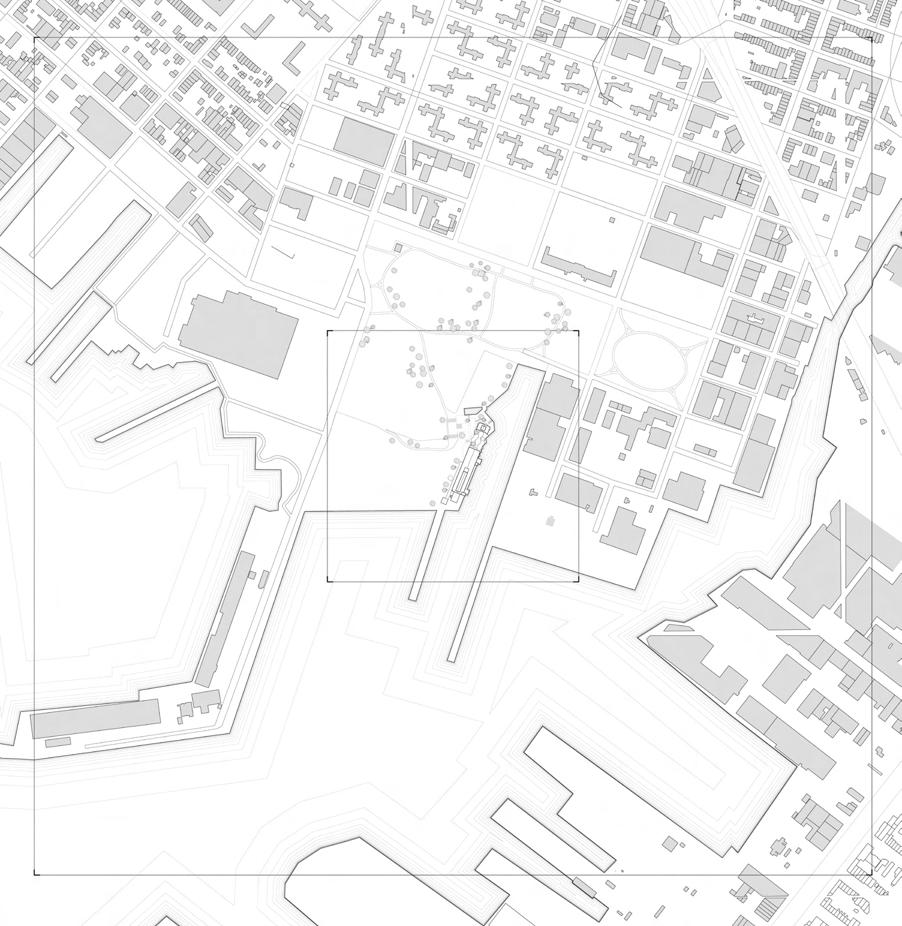

Adaptive reuse of an abandoned grain terminal in Red Hook, New York City posed crucial questions about equity in public housing projects and the need to satisfy the demands of the project’s rich and historically complex neighborhood. Inspired by the vulnerabilities of American housing projects to climate events like flooding, this proposal breaks apart the silos and completely opens up the space within to contrast with typical narrow, dark housing tower typolgy in the United States. These openings are screened by wooden facades of varying densities depending on the activity within.

The massive scale of the existing silo configuration allows plenty of room to address housing for diverse groups, from students to familiies to informal groups of two or three people. A variety of housing typologies are situated within the new silo configuration to accomodate each of these groups. Additionally, dedicated pockets of space between dwelling configurations are devoted to blue/green job training and workshop areas, preparing emerging professionals in the neighborhood to work on infrastructure projects that will help mitigate the escalating climate crisis impacting New York and other coastal American cities.

Situated in the industrial neighborhood These massive, 8” thick concrete silos retrain a diverse population that includes

neighborhood of Red Hook in Brooklyn, NYC, the housing complex takes advantage of the abandoned Gowanus Bay grain terminal. silos were used to store grain when shipping lanes still favored the neighborhood, but will be repurposed to help house and includes both families, low-income housing seekers, and Red Hook’s high concentration of artists.

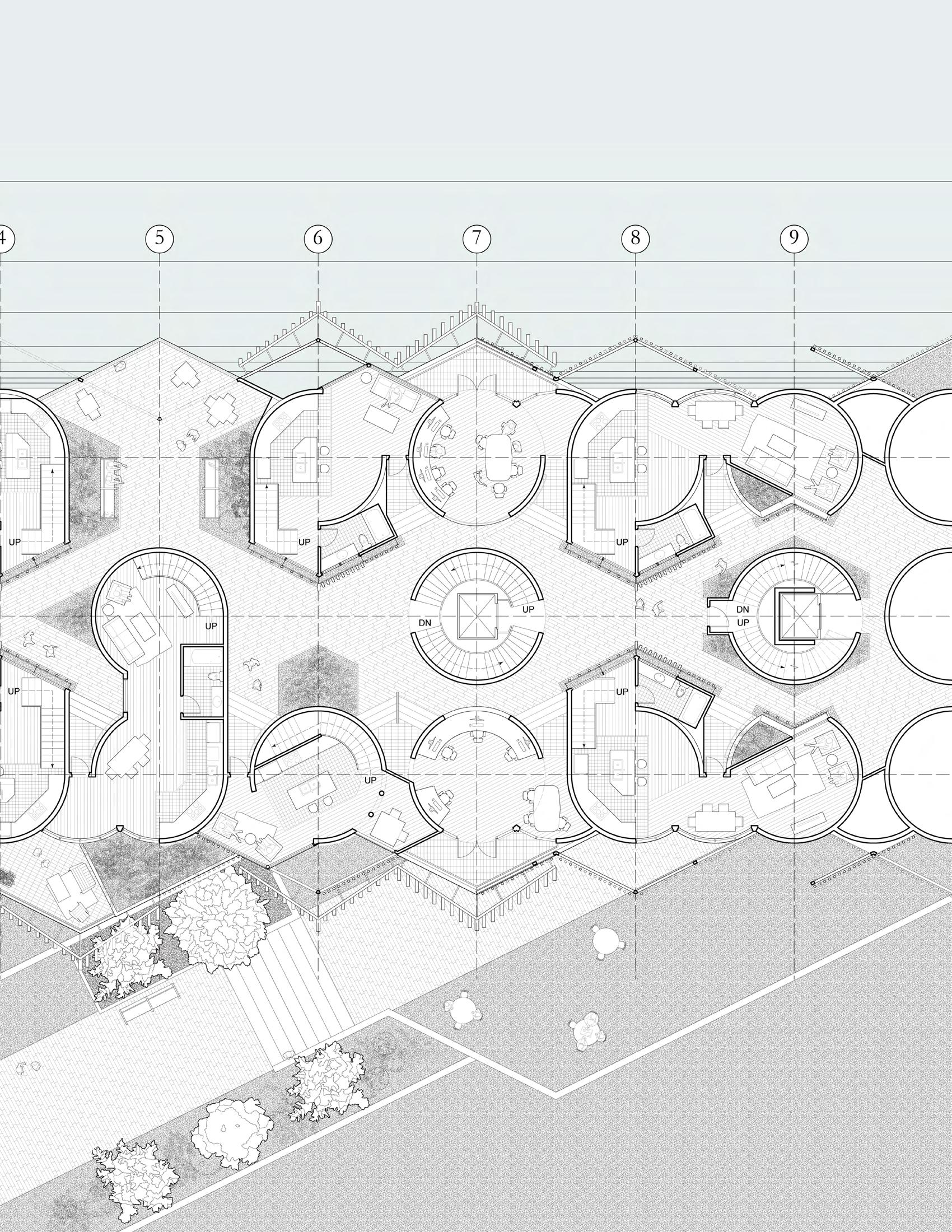

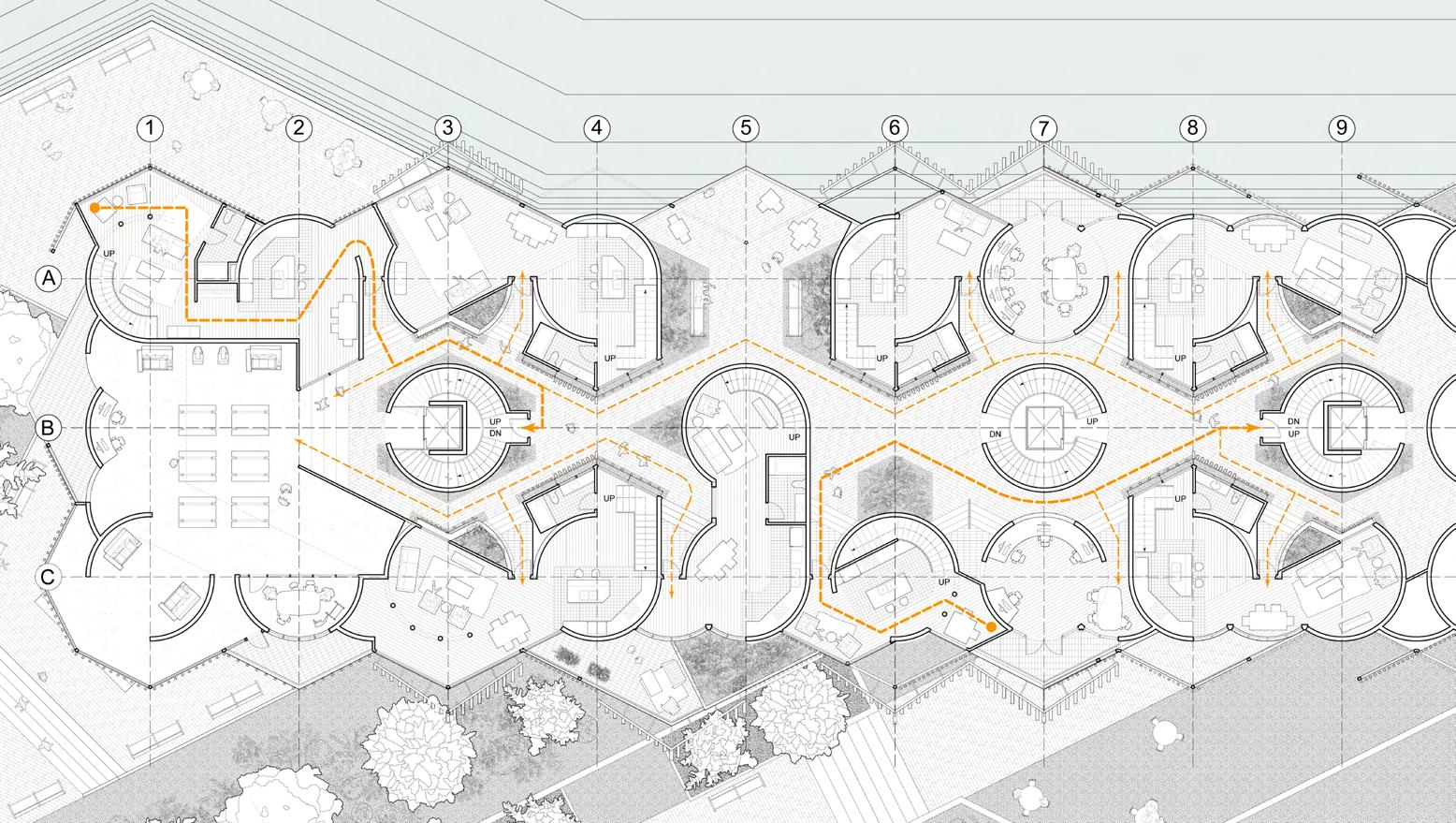

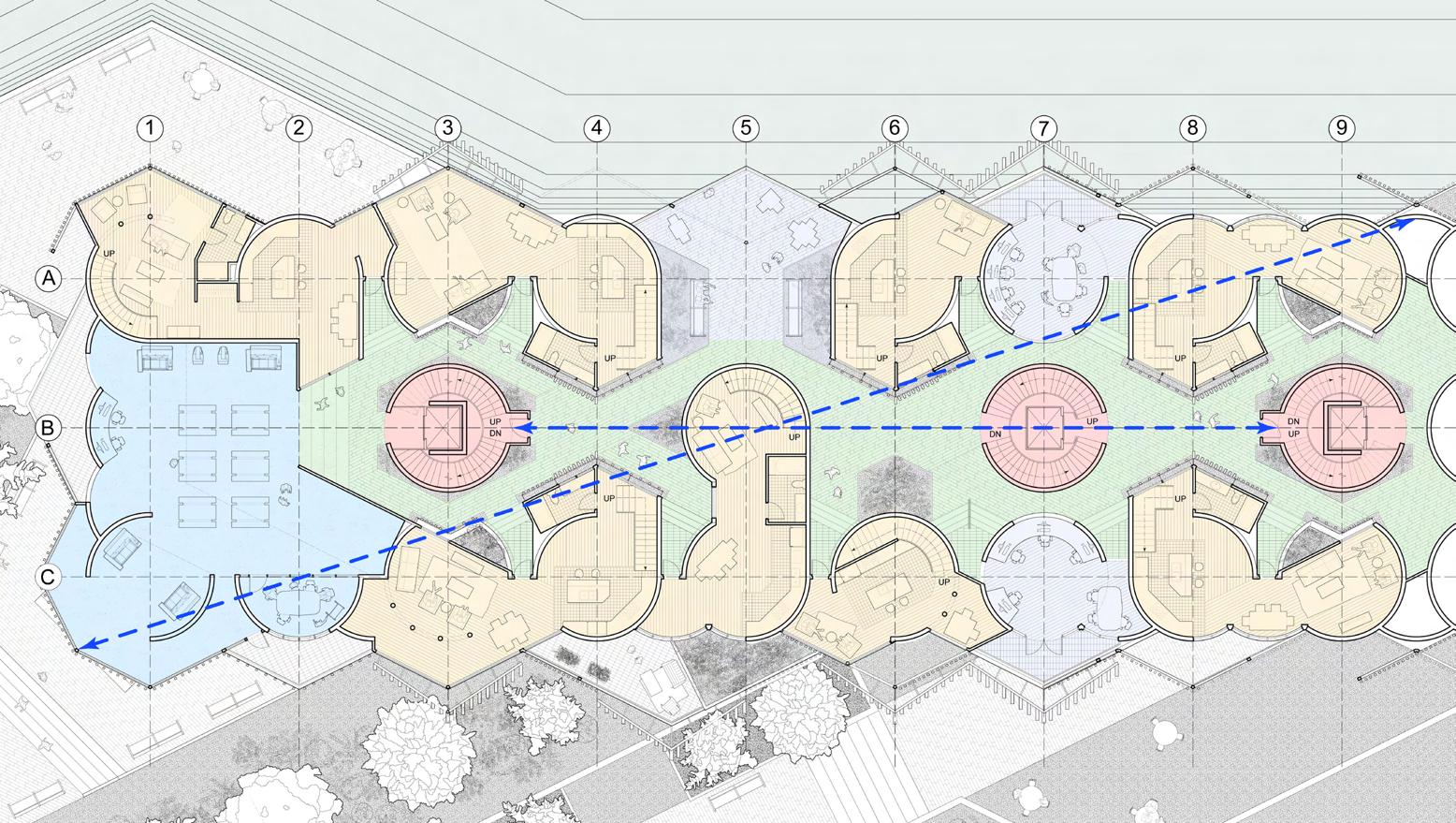

Below: Typical Floor Plan (first level)

Spaces between housing units are devoted to sustainable ‘blue-green’ job-training programs, which will help the community adapt to tomorrow’s ever-changing career landscape and attract a variety of tenants ranging from individuals to families. A similar variety of unit types will accommodate these tenants.

Below: Elevation (West)

All housing units are double-level and offset upwards from the interior circulation to differentiate them from a generic apartment condition. The living spaces emulate characteristics of homes rather than temporary dwellings, and are screened with differing densities to provide privacy as needed.

Because of the abundant space available to it, the project emphasizes openness and lightness to contrast with the usual condition of narrow, dark hallways employed by most apartment buildings while preserving feelings of privacy and security for the residents.

IBC 1005.1 Minimum required egress width. The total width of means of egress in inches shall not be less than the total occupant load served by the means of egress multiplied by the factors in IBCTable 1005.1 and not less than specified elsewhere in the code.

IBC 1014.3 Common path of egress travel is compliant for all spaces in the building. For every residence, the most remote point within the unit to its exit does not exceed 75 feet.

IBC 1016.1 Max Egress Travel Distance is compliant for all spaces in the building. For every residence, the most remote point to a fire exit lies within code allowable distances, even without a sprinkler system.

IBC 1015.21 Two exits or exit access doorways. The two most remote fire stairs in the building are placed a minimum distance apart of one-half the length of the maximum overall diagonal dimension of the building, even without sprinklers.

Max Egress

Travel Distance: 125’ - 3”

Max Egress

Travel Distance: 129’ - 9”

Left: Exit Access Code Analysis | Right: Egress Width Code Analysis

To explore the actual viability of this project in real life, a post-review code study was conducted on Pieces of Community to see if it satisfied IBC criteria for egress and fire safety. Although it did not meet some requirements, it passes others well, proving that the distinction between academic and professional work need not be so sharp.

In collaboration with Susie Dole

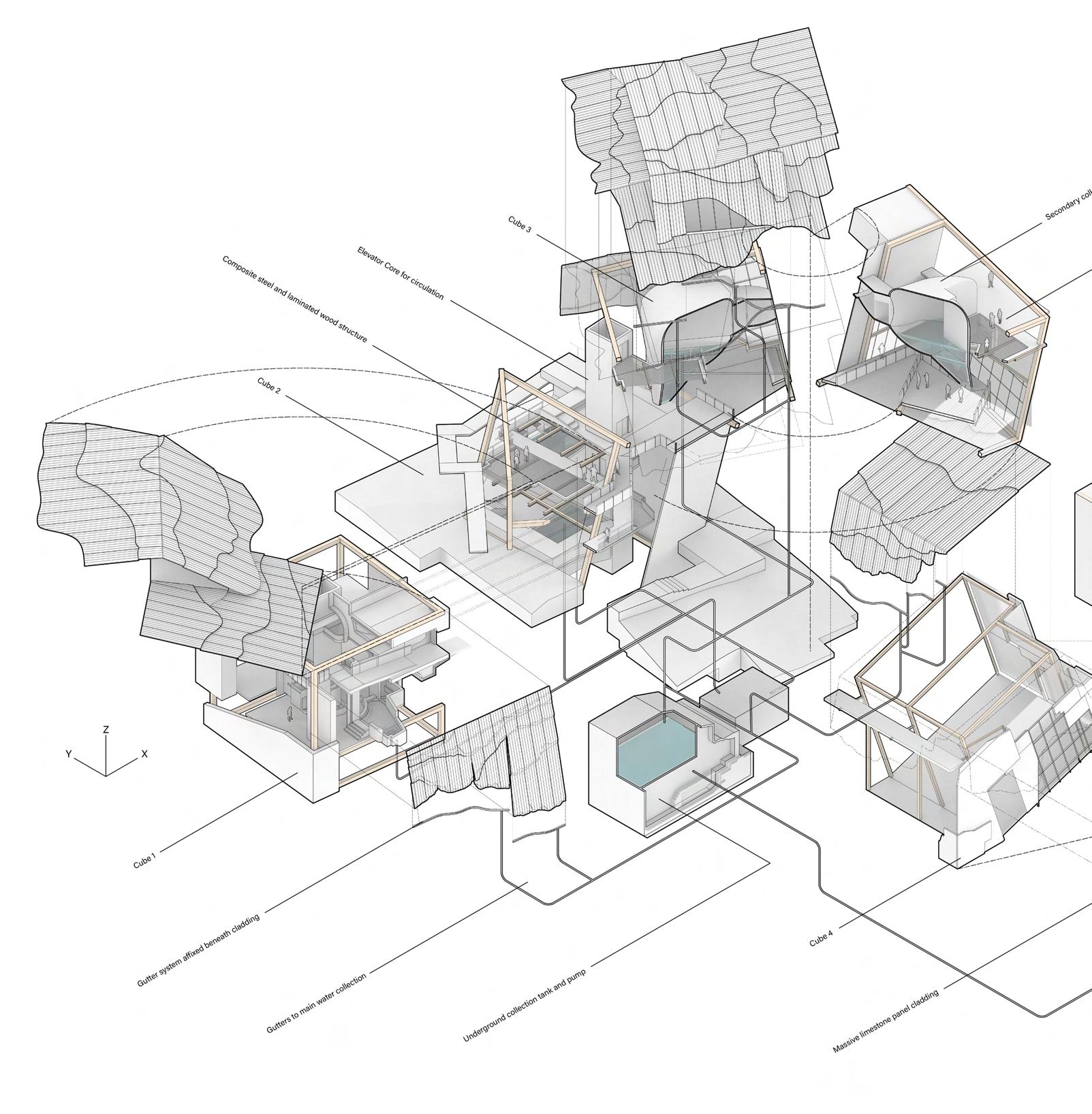

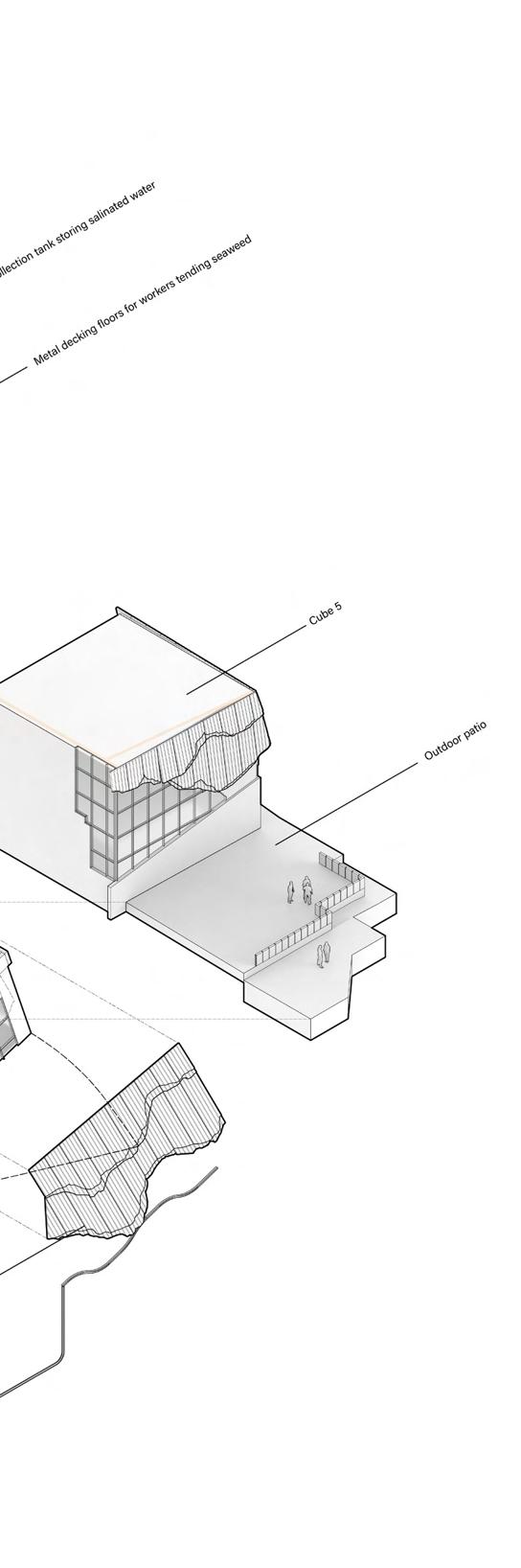

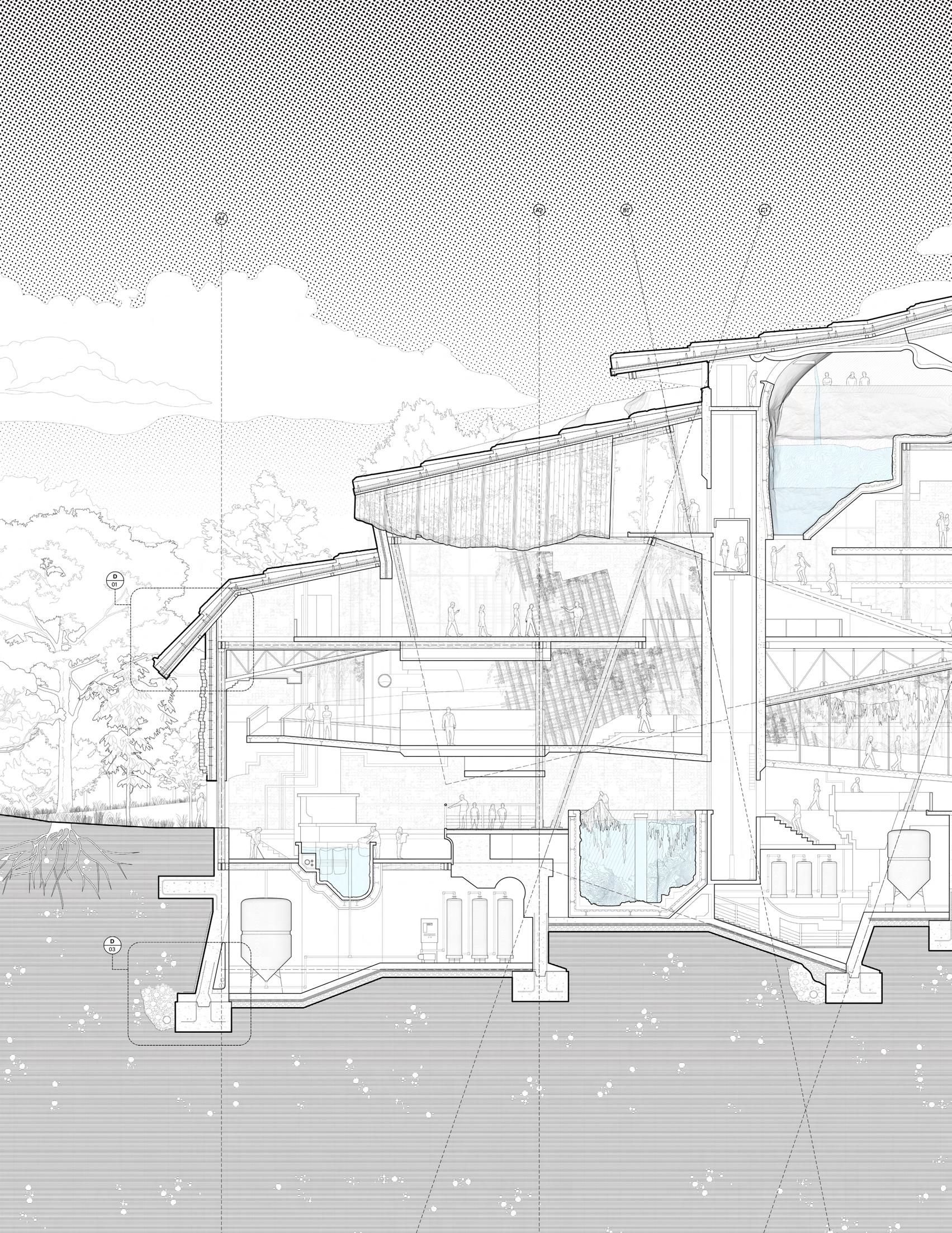

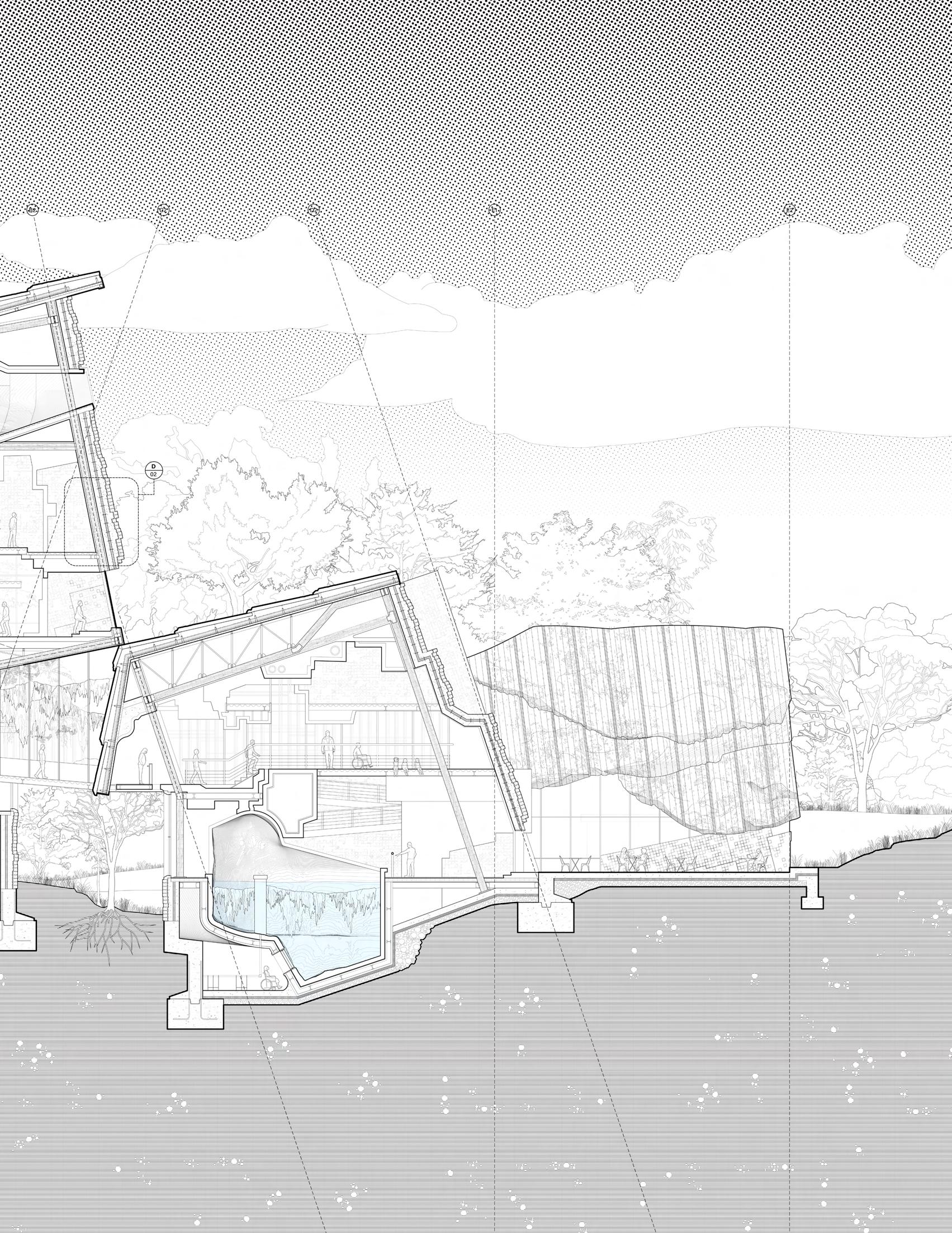

In a studio focused on dissecting advanced food growing technologies, we designed a seaweed growing facility adjacent to Philadelphia’s horticultural center. Although seaweed farming has existed for millennia, it has historically remained a lowtech and labor intensive process. Widespread in east and southeastern Asian countries, most operations consist of handplanted and harvested varieties of seaweed and kelp in shallow waters. Furthermore, seaweed farming is a nearly non-existent industry in the United States, with only a few recent enterprises beginning in Maine, Alaska, and New York to supply growing consumer demand. Some operations grow seaweed on land in a series of saltwater-supplied basins and tanks, while others make use of equipment to grow higher volumes in waters that are deeper than most farms but still close to shorelines.

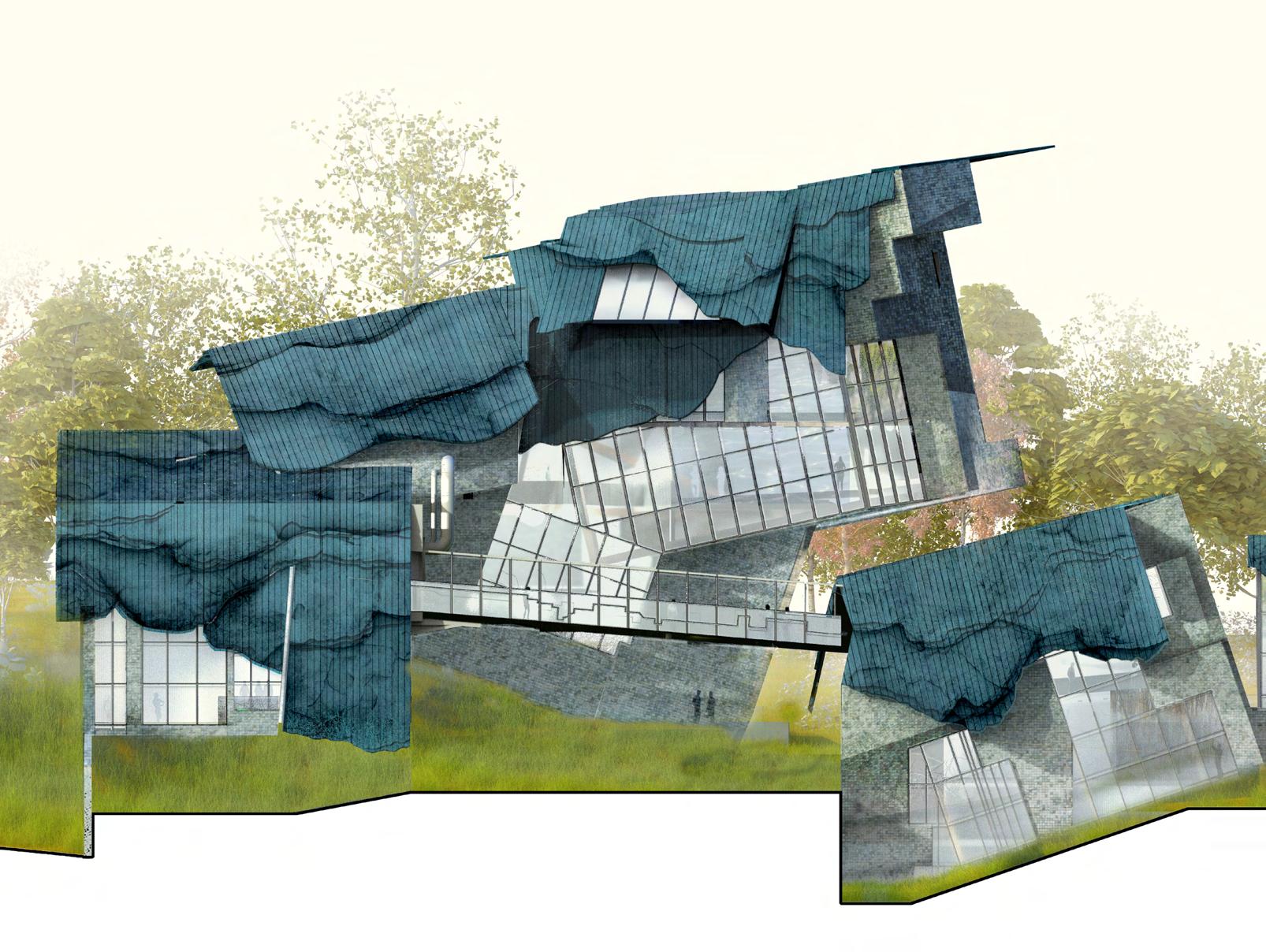

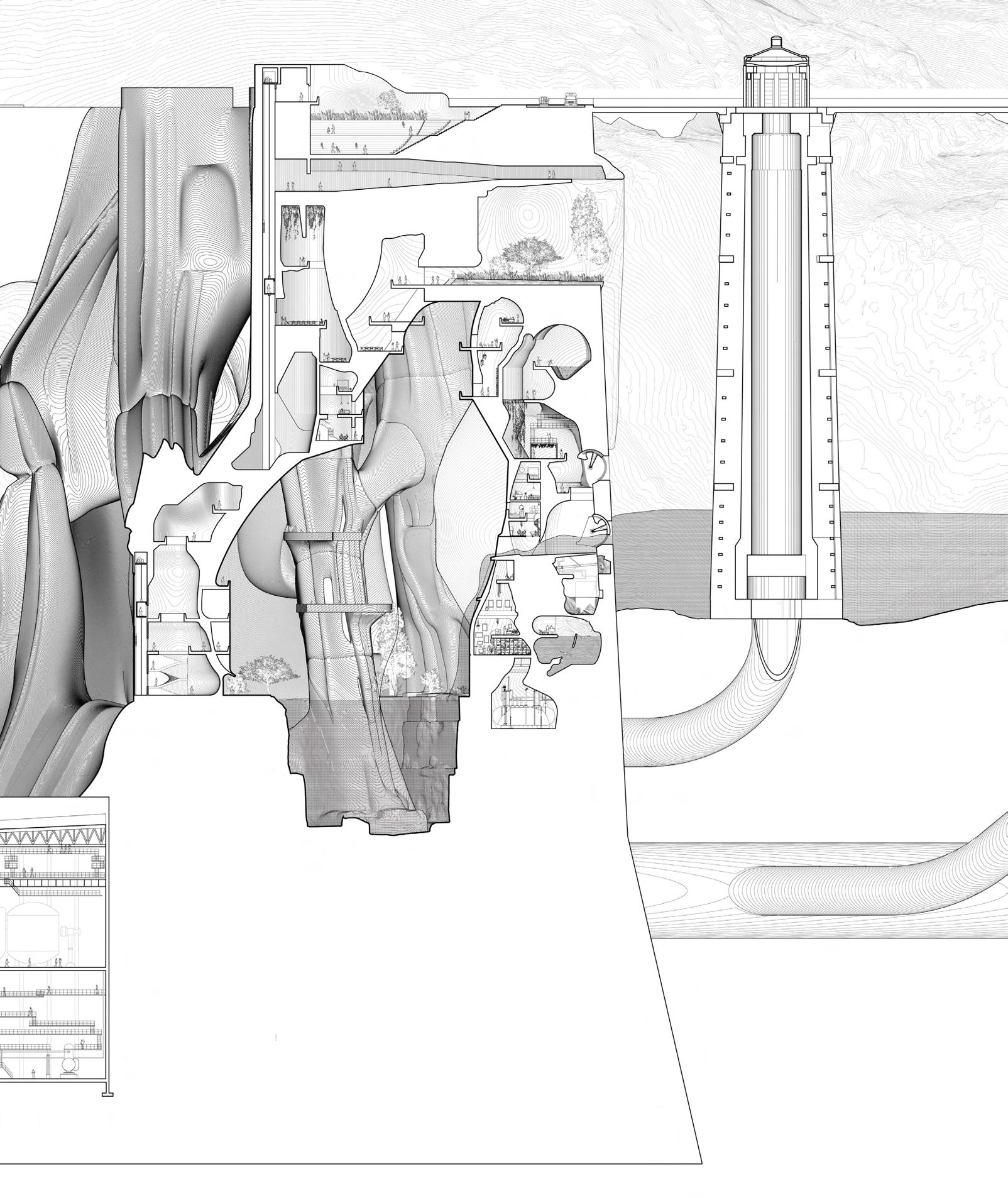

Because seaweed can grow with minimal food and equipment whether on land or in sea so long as it has salt water, we took liberties with the artistry of this process and made it the central experience of an aquacultural facility sited near Philadelphia’s Fairmount Park horticultural center. Drawing inspiration from the various figures in Louis Kahn’s castle sketches, artistically shaped, complex growing tanks are distributed throughout the building and generate interest for visitors receiving tours of the facility. These visitors are led throughout the space on a series of gently sloping lamps while workers cultivate seaweed below. The promenade terminates in a cafe where visitors are welcome to taste what they witnessed growing during their tour.

The experience of the facility winds its way through five interconnected cuboid masses. Spaces that serve workers tending the tanks of seaweed and visitors are disjoined, yet visible to each other throughout the facility. This allows visitors to witness the entire process of growing seaweed products at a safe distance.

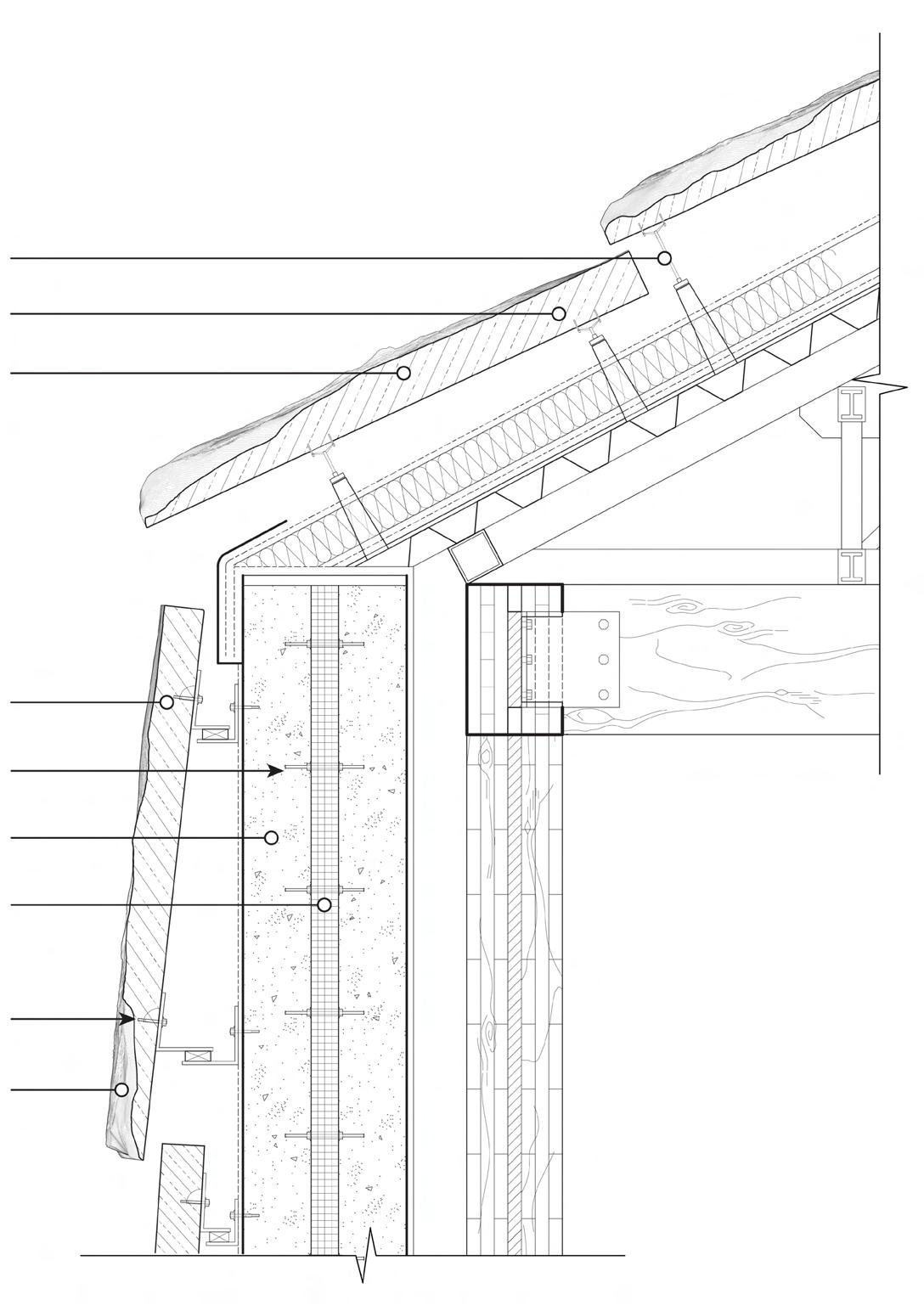

Standoffs to mount panels to roof assembly

Multi-axis connectors for panels

Limestone panels on sloped roof PVC or liquid applied membrane

6-10” Polyiso insulation

Densglass

3” Metal Decking Square tube steel Flashing

4-6” Limestone panels

Thermomass wythe ties, 18” O.C. Continuous composite concrete backup wall

4” rigid insulation

Fisher-style anchors, back-cut into stone panels

CNC-milled live edges of panels

Above: Stone Panel Detail | Right: Granite ‘Brick’ Wall Detail

Massive, heavy limestone panels create a monolithic facade that evokes the weight of water and paradoxically reverses the expected rustication of buildings. Special granite blocks cast into the walls of the facility further evoke heaviness, but to a lesser degree than on the facility’s roof.

Individual granite “bricks”

Continuous composite concrete backup wall

4” rigid insulation

Thermomass wythe ties, 18” O.C.

Clip angles to connect composite timber beams to steel substructure Steel framing to support slab edge

Weep holes between individual stones

Chisled-out key for concrete precast wall construction

Wedge insert box and steel angle supporting bottom of granite brick wall

In collaboration with Natalie Perri

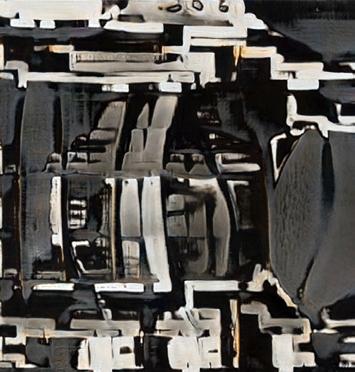

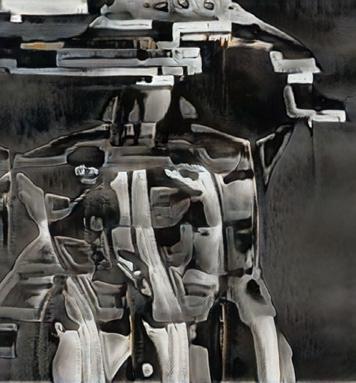

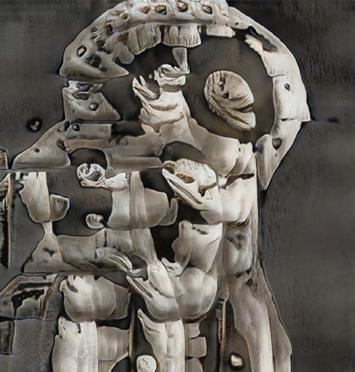

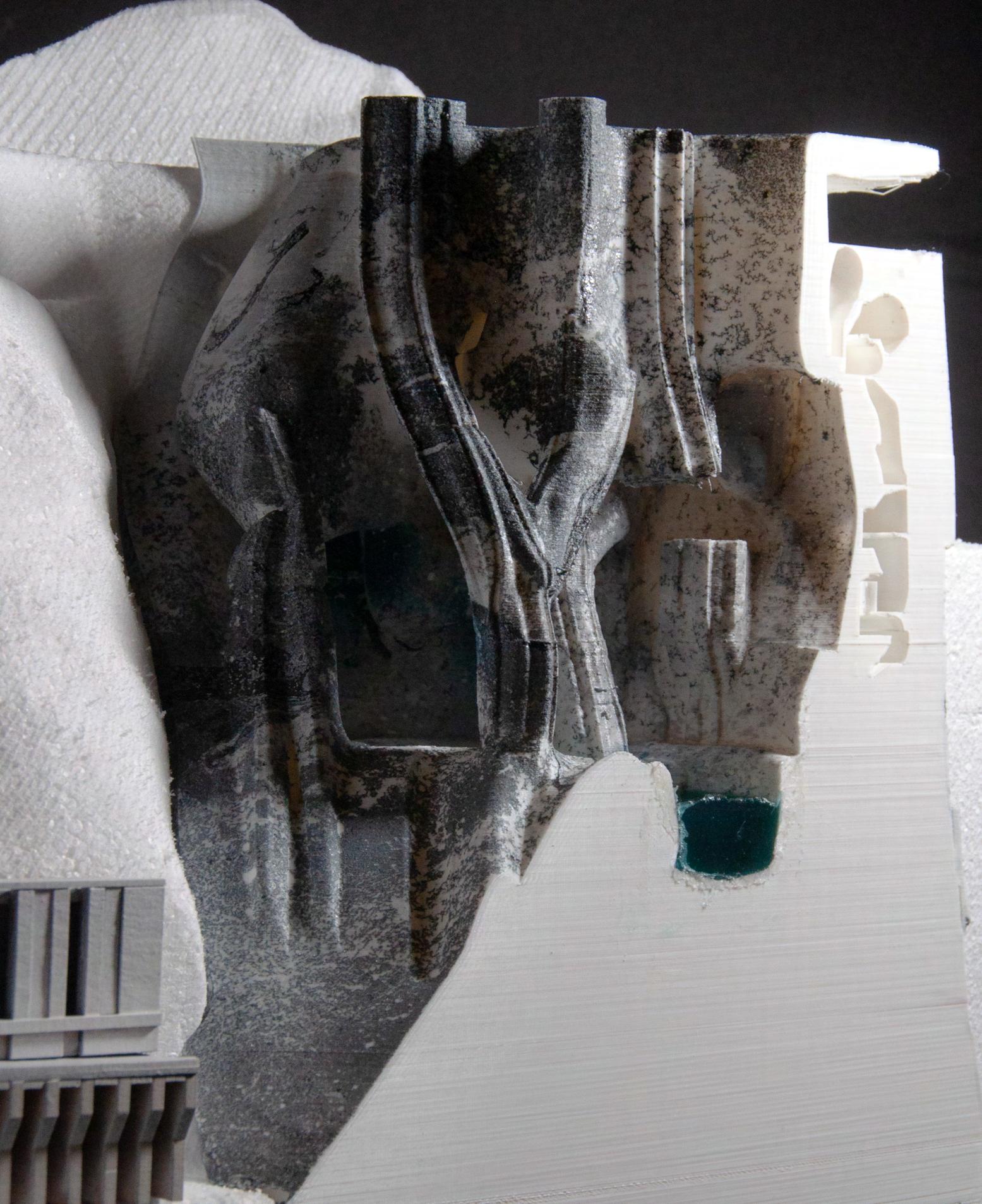

In examining the concept of the sublime through a contemporary lens, we turned to AI generated images as an incubator for ideas to approach the water crisis in the Southwestern United States. Our studio studied and visited the Hoover Dam, a monumental piece of American infrastructure that literally shaped the southwest. With the effects of climate change putting the Dam’s ability to distribute water and electricity in jeopardy, we were tasked with imagining an architectural approach to address the site’s future.

Inspired by the tectonic properties of our AI trainings, we imagined a future where the Dam is once again transformed into a gargantuan infrastructural project. In a future where the Colorado River can no longer sustain the needs of the five states it feeds, what is left is instead routed through a massive public park complex situated inside the structure. Flexible-use spaces are also nestled into the columns cast on the dam that support its new structure, which could conceivably serve as temporary worker’s housing during construction, facilities for state politicians to renegotiate water rights between the American Southwest, or any number of public programming initiatives.

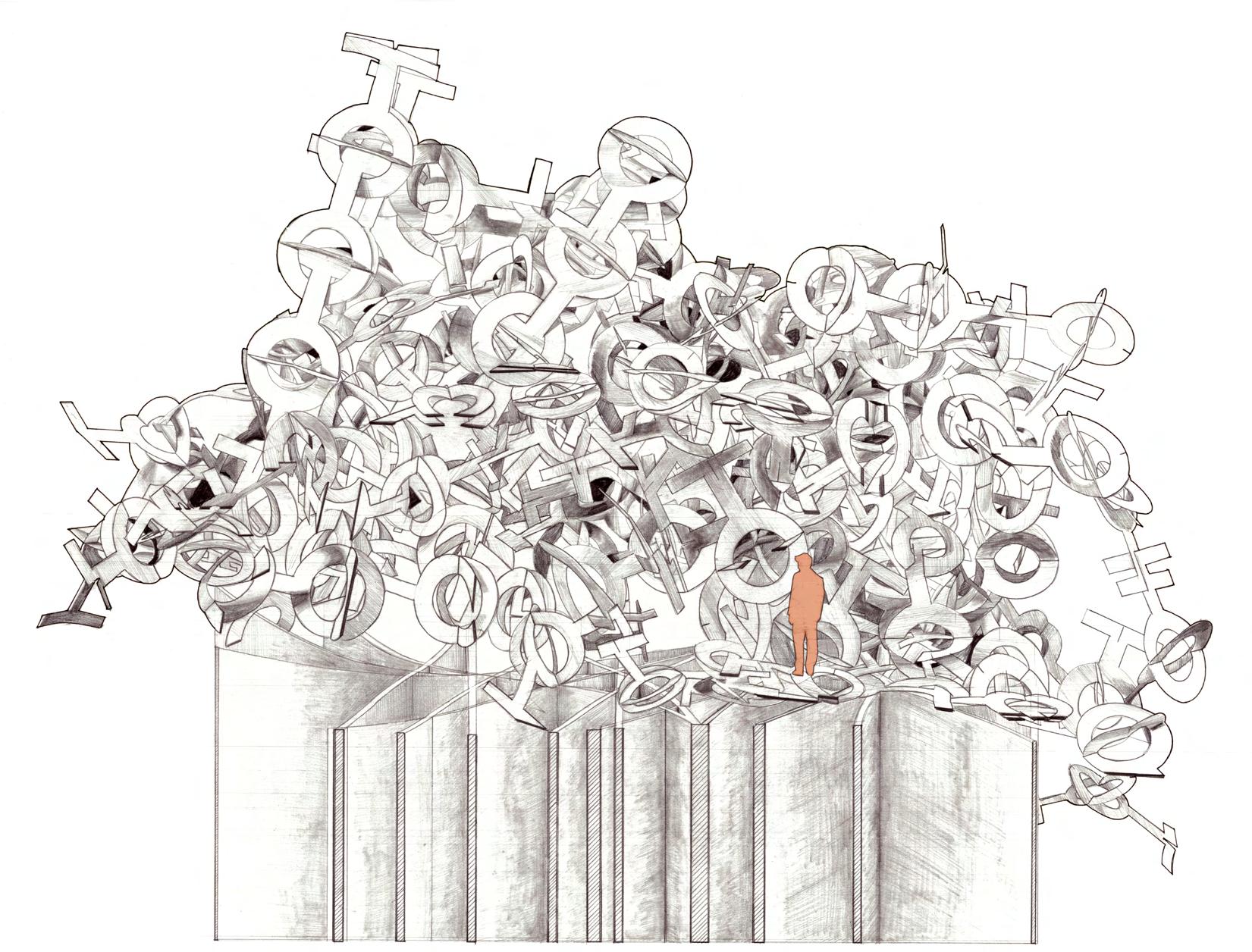

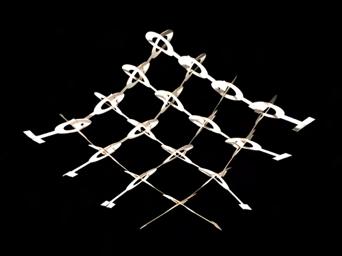

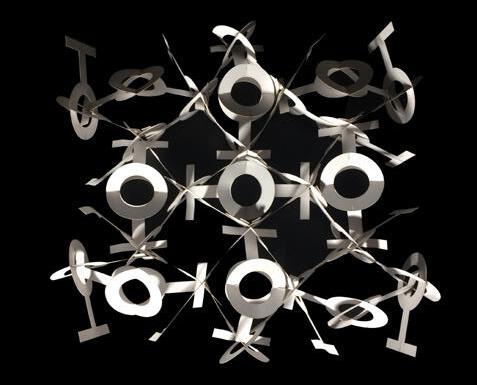

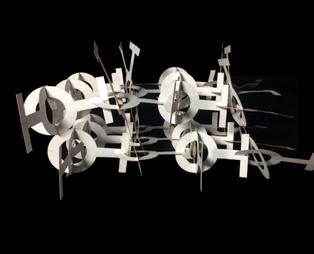

Using StyleGan AI trainings, we compiled images of objects with formal properties we wanted to iterate upon. Assemblages of corals and statues were mixed with the tectonic properties of machinery and camera cross sections, resulting in a spatial idea with separate pieces but a clear organizational logic and structural idea.

Excavating the dam opens up a massive space within, which will fill with water diverted from the Colorado River once Lake Mead inevitably reaches deadpool level. Like the lake, this space will provide opportunities for recreation, sport, and relaxation to visitors while couched existing dam infrastructure.

inevitably couched within the

Solo Work

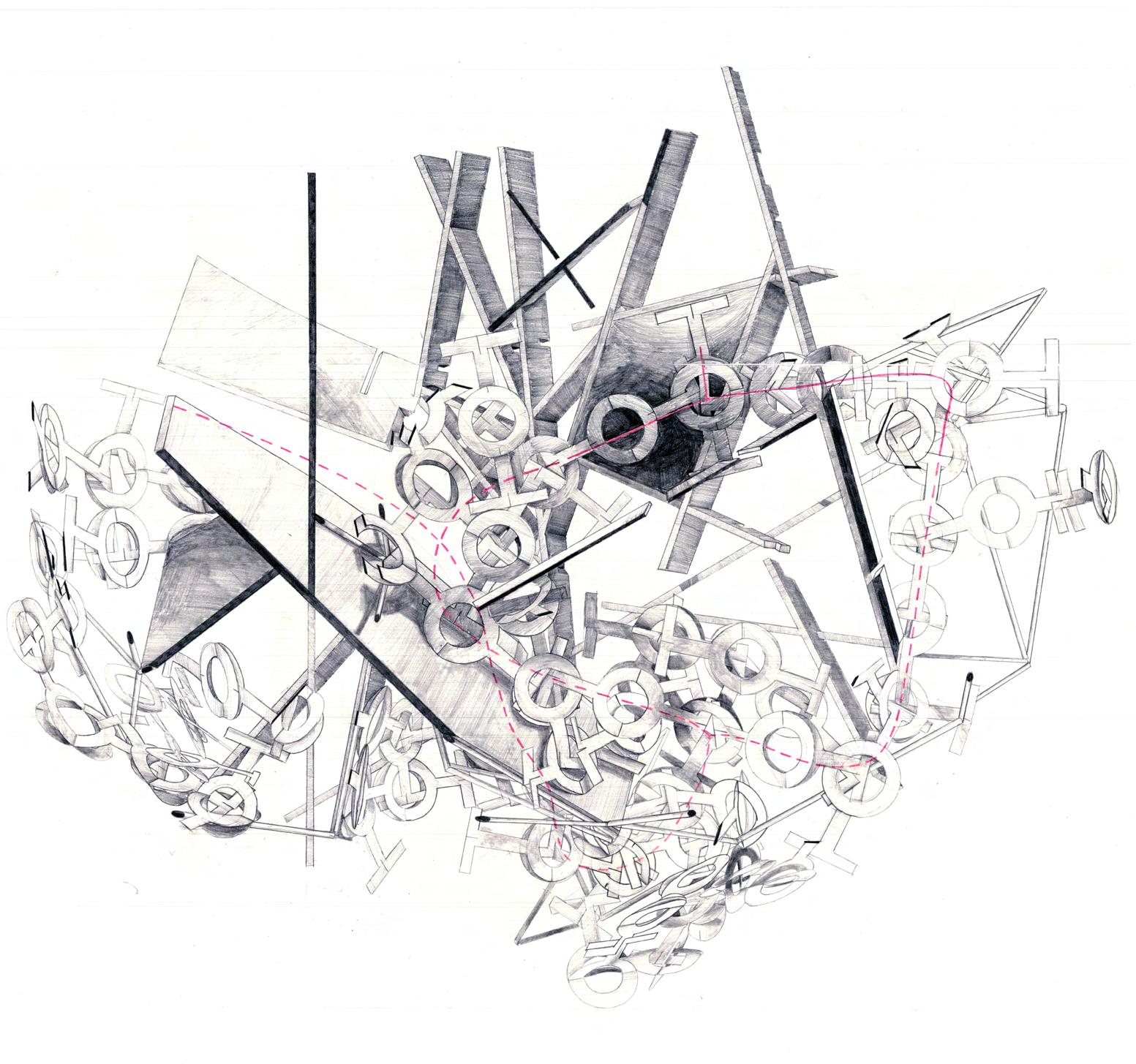

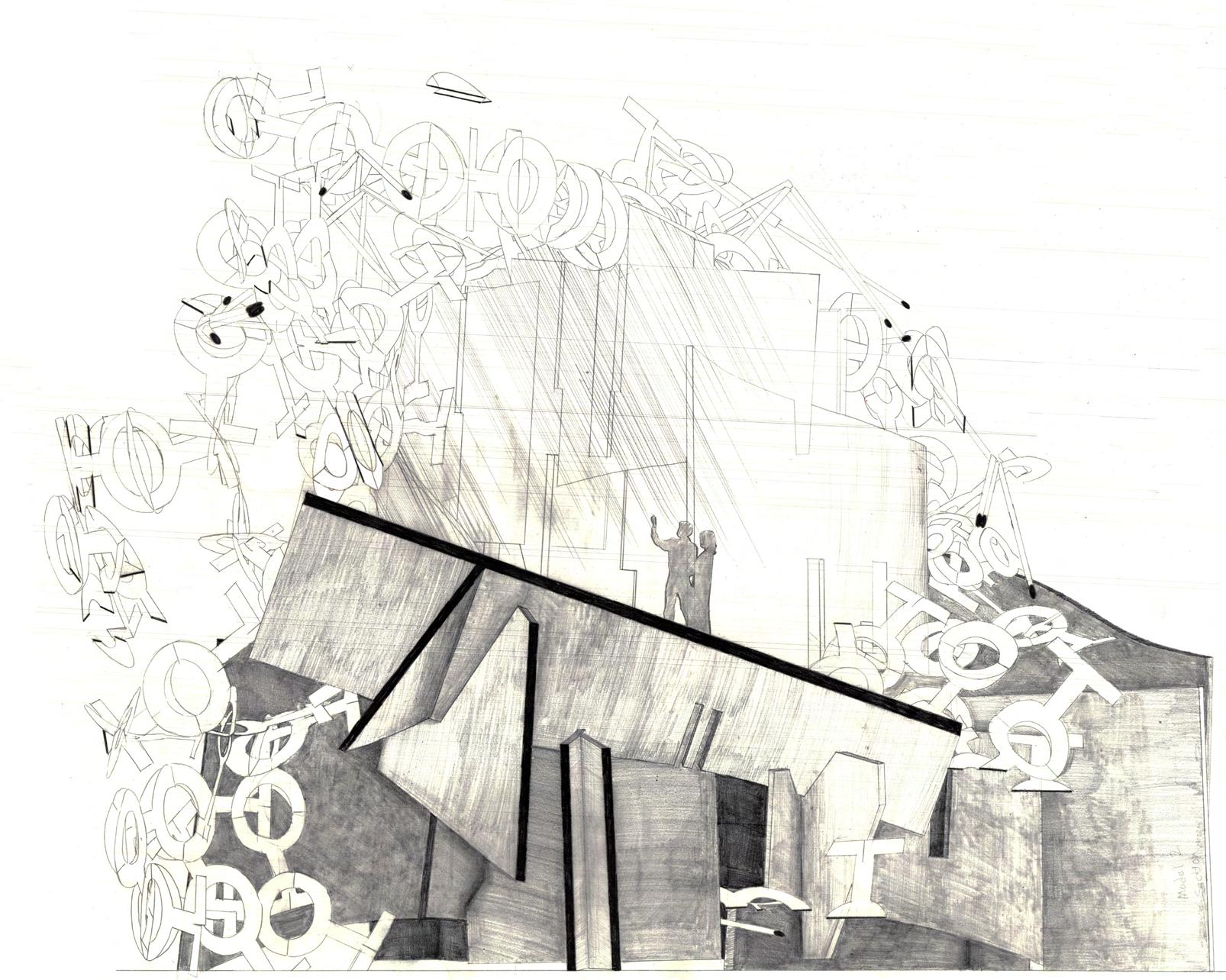

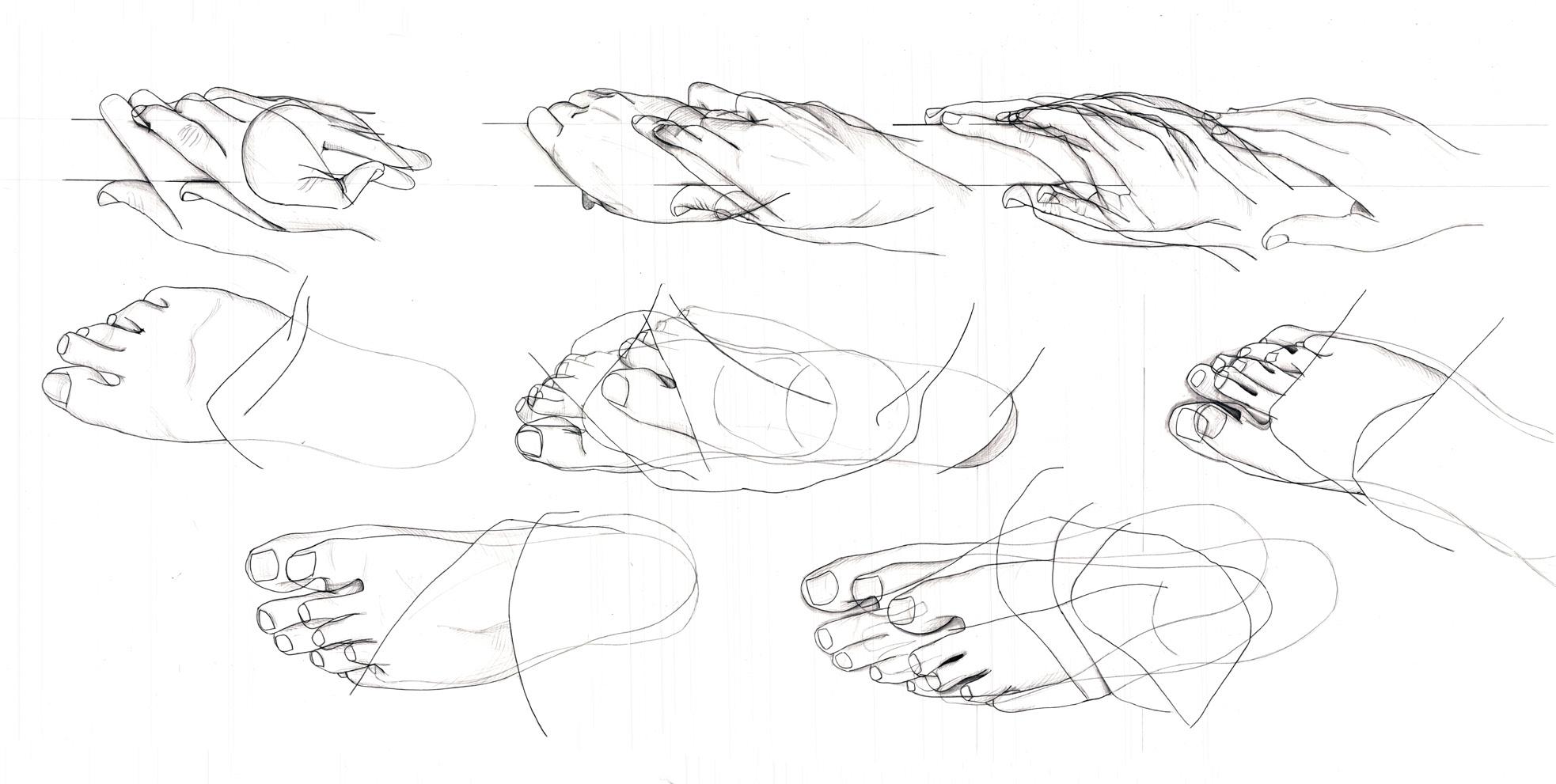

Many early undergraduate projects required the ability to render scenes by hand to describe the atmospheric qualities of space like light and darkness; movement; or to accurately depict the aggregation of small parts. A selection of these renderings is shown below, accompanied by descriptions of what they seek to convey. These hand sketches often served as the basis of further architectural explorations for undergraduate works. The works depicted here are intended to convey technical skill rather than conceptual rigor or architectural ideation.

of human bodies within the spaces themselves?

These studies sought to answer that question by carefully recording human movement on a staircase in Temple University’s Alter Hall.

The observations progressed from general to detailed, starting with sketches of the movements of passerby and our own physical bodies. Later, we undertook a group project in which someone performed a choreographed dance down the stairs, which was carefully measured and utilized for later model-making.

These studies recording University’s

The observations with sketches bodies. performed carefully

space defined by physical boundaries, or by the habitation of human bodies within the spaces themselves? studies sought to answer that question by carefully recording human movement on a staircase in Temple University’s Alter Hall.

observations progressed from general to detailed, starting sketches of the movements of passerby and our own physical Later, we undertook a group project in which someone performed a choreographed dance down the stairs, which was carefully measured and utilized for later model-making.

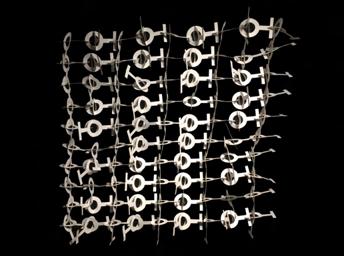

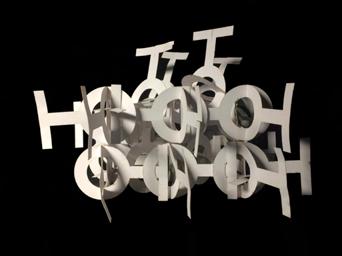

In this early studio at Temple, we created a system of paper modules and explored how they could form space with different atmospheric qualities. The above hand-drawn section on vellum speculates on qualities of light and darkness.