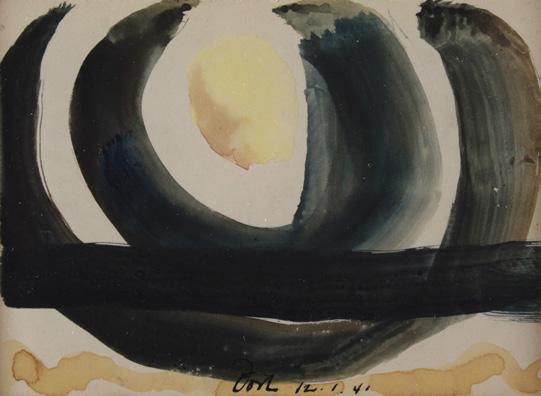

Arthur Dove

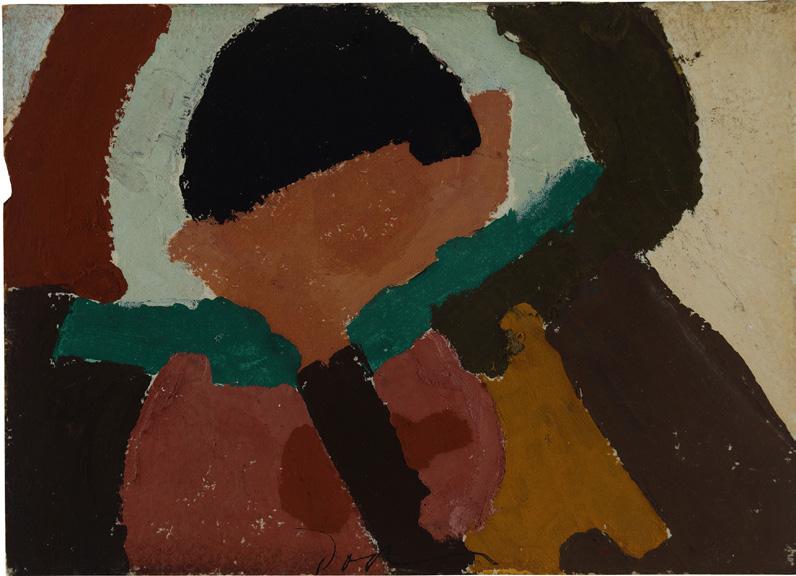

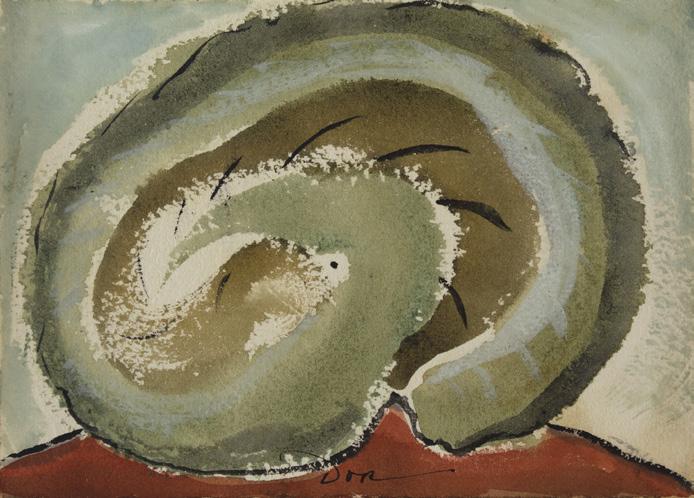

Moon, 1935

From the beginning, Dove placed a premium on intuition, an intangible source, that could buttress his scrutiny of nature’s vast inventory, its random rhythms, and intense meteorological dimensions. There had been a great deal of discussion on the role of intuition in the formation of art in the pages of Camera Work in 1912, most notably in the writing of the French philosopher Henri Bergson whose ideas imprinted Dove’s understanding that his emotional life was a viable origin for painting. This was a conviction that shaped the arc of his career and accounts for the ongoing sensuality and uplift of his work at every phase.

— Debra Bricker BalkenDove is the only American painter who is of the earth. You don’t know what the earth is, I guess. Where I come from the earth means everything. Life depends on it. You pick it up and feel it in your hands . . . No, Marin is not of the earth. He walks over the earth, but Dove is of it.

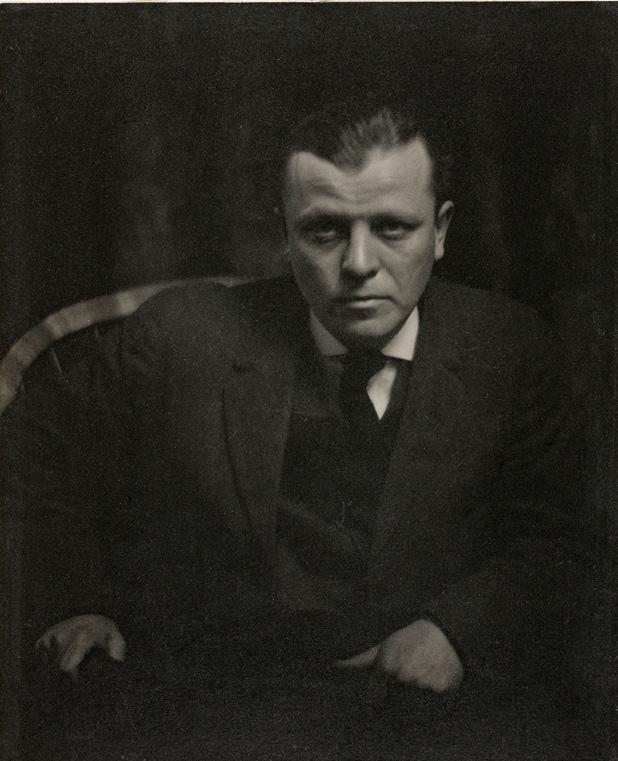

— Georgia O’Keeffe Arthur Dove, 1912, photographed by Alfred Stieglitz

Arthur Dove, 1912, photographed by Alfred Stieglitz

When Arthur Dove (1880–1946) proclaimed in 1916 that his goal was to elaborate on “the sensations of light from within and without,” his reputation as America’s foremost abstract painter of the early twentieth century had been gestating for almost five years. The distinction was remarkable, if not astounding, for an artist who was not only a late convert to painting but also to the modernist ethos in invention, its driving mechanism.

After graduation from Cornell University in 1903, Dove had got his start as an illustrator in Manhattan where he worked on a free-lance basis for mass media publications such as McClure’s, Scribner’s, and Cosmopolitan Magazine. Yet the requirements to enact his patron’s prescriptions for cartoons and line drawings that were alternatively topical or whimsical never satiated a desire to pursue his own subjectivity, or “inner consciousness” as one early writer put it. There were too many impediments to accessing his own creativity, Dove deemed, foremost among them illustration’s de rigueur need for figuration.

Dove’s first attempts at painting failed to augur or even hint at the astonishing abstractions that he embarked on around 1910 after returning from a fifteenmonth sojourn in France. There was little build-up, that is, to his series of small panels that grew from a honed study of nature. Not only do these abstract compositions dispense with the voluminous brushwork that had defined his sun-drenched agrarian scenes of France’s coastal regions but there is no lingering reference to a specific site and its unique topographies. For all their charm and allure, the landscapes that Dove produced abroad had been dependent upon the begone movement of Impressionism where nature was construed as an atmospheric wonder. Still, Impressionism’s preoccupation with light, with its resonant sensuality, would hold him over a lifetime. Back in the United States, his project became more disciplined and probing. While camping in the woods in 1909 near Geneva, New York where he grew up as a child, he began to examine the way in which the eye processes light sensations into color. He was overcome by a huge revelation that natural specimens—be they the bark of a tree, a flower, bird, or butterfly—proffered a world of chromatic variety that could be distilled into abstract statements that paralleled the vitality and thrust of modernist painting.

Dove admitted that his work in France had amounted to a “blind alley,” however welcome a diversion from the constraints of illustration. Yet, it took him exhibiting at Alfred Stieglitz’s 291 Gallery in Manhattan in 1910 to fully recognize that his work required greater rigor to bypass lingering aesthetic conventions, even the more advanced strategies of Post-Impressionism where the architecture of the picture plane was dismantled and reconfigured by figures such as Paul Cézanne whom Stieglitz had exhibited. Stieglitz, who had also shown the likes of Henri Matisse, Pablo Picasso, and the paintings of American artists such as Marsden Hartley, John Marin, and Max Weber—all before the landmark Armory Show in 1913—would claim that Dove’s bold advances beyond known representations of nature in pursuit of the “condition of light,” as Dove also phrased it, was without precedent, however. He averred that Dove landed in the precincts of abstraction “independently” of prevailing experimentations. As Dove himself later proclaimed, “I could not use anothers [sic] philosophy except to help and find direction any more that I could use anothers [sic] art or literature.” Not only does the declaration reinforce Stieglitz’s affirmation but it emphasizes the artist’s mandate to counter expectation, to chart new visual territory. Such would be his lifelong ambition.

Dove’s abstractions of 1910/11, however pictorially intrepid, were never exhibited during his lifetime. Nonetheless, they spawned a number of subsequent pastels that when exhibited first at 291, and later at the Thurber Galleries in Chicago, were critically acknowledged for their extraordinary assurance and singularity. One reviewer noted that they represented a first for an American artist and commented on their “absolute originality.” These works— authoritatively dubbed “The Ten Commandments” (most likely by Stieglitz)— along with the subsequent trajectory of his work were given to capturing the ephemeral processes of nature, such as growth patterns, the curvature of the earth, and “the misty folds of the wind,” as Dove described it.

It is unlikely that Dove knew of the work of Wassily Kandinsky in 1910, although he read his seminal tract, Concerning the Spiritual in Art, which was excerpted in Stieglitz’s quarterly publication, Camera Work in 1912, the year of Dove’s first and only solo show at 291. Kandinsky had been credited with producing the first abstract paintings in Europe—that is until recently when Hilma af Klint, who similarly mined her psyche for pictorial equivalents is recognized as the actual forerunner. Kandinsky, moreover, had exhibited in New

York, most notably at the Armory Show in 1913 (unlike af Klint). Yet, Dove’s abstractions, for all of their prescience, are not the outgrowth of metaphysical inquiry. They operate more as investigations of the myriad optical effects that nature proffers. To be sure, there are parallels with Kandinsky’s analogies of painting with music and their mutual abstract properties—a crossover that Dove gleaned from the older artist—but their formal investigations remain entirely separate. Nature would endure as Dove’s abiding subject, even late in his career when his analysis of organic form became non-objective, no longer an outgrowth of observation.

From the beginning, Dove placed a premium on intuition, an intangible source, that could buttress his scrutiny of nature’s vast inventory, its random rhythms, and intense meteorological dimensions. There had been a great deal of discussion on the role of intuition in the formation of art in the pages of Camera Work in 1912, most notably in the writing of the French philosopher Henri Bergson whose ideas imprinted Dove’s understanding that his emotional life was a viable origin for painting. This was a conviction that shaped the arc of his career and accounts for the ongoing sensuality and uplift of his work at every phase.

Part of Dove’s emphasis on feeling can also be attributed to his aversion to the rampant materialism that had begun to alter American culture in the early twentieth century. Like Stieglitz and writers such as Sherwood Anderson, Paul Rosenfeld, and Waldo Frank, who followed his work, Dove viewed the mechanization of the urban landscape, mass production, and new proliferation of commodity objects as a detriment to the engagement of feeling. Nature, by contrast, with its omnipresent fecundity, could serve not only as a wellspring but as an analogue for the creativity and generative powers of the artist.

In 1921, Anderson wrote to Dove, who had just come out of a fallow period and overly taxed by the demands of eking out a living as a chicken farmer— such had become his resistance to working as an illustrator: “There is some faint promise of rebirth in American art but the movement may well be a stupid reaction from Romanticism into realism—the machine. To be a real birth the flesh must come in. And, that’s why, I suppose, I have, since seeing the first piece of your work, looked to you as the American painter with the greatest potentiality for me.” Anderson’s reference to the “flesh” was potent and would set the tone for subsequent interpretations of Dove’s work. As the decades of

the 1920s and ’30s unfolded, and Dove’s painting was routinely exhibited at Stieglitz’s later showcases for art, numerous writers would frame his painting in Freudian and sexualized terms by linking the occasional phallic shafts of both vegetal and architectonic forms, as well as his surging cloud formations and rise of the sun at dawn as evidence of his “virile and profound talent.” Critic Elizabeth McCausland would later enlarge upon this metaphor, writing, “He sees life as an epic drama, a great Nature myth, a fertility symbol.”

Georgia O’Keeffe, with whom Dove would be critically paired by writers such as Rosenfeld, said it more succinctly when she announced that Dove “is the only American painter who is of the earth.”1 By that she meant his radiant distillations of nature, with their “sensations of light within and without,” were the outcome of a heightened intuition and abstract sensibility that stood out within American art in the first half of the twentieth century.

1 Arthur Dove, “Explanatory Note,” in The Forum Exhibition of American Painters, exh. cat., ed. Willard Huntington Wright (New York: Anderson Galleries, 1916; repr., New York: Arno Press, 1968), n.p.

2 Samuel Swift, “Review of Picabia Exhibition,” The Sun (New York), March 1913; reprinted as “Samuel Swift in the N.Y. Sun,’” Camera Work, nos. 42–43 (April–July 1913), 48–49.

3 I am paraphrasing Torr here. See Helen Torr, “Reminiscences,” n.d., Arthur and Helen Torr Dove Papers, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution (hereafter Dove papers, AAA).

4 Arthur Dove, quoted in Helen Torr, “Notes,” n.d., Dove papers, AAA.

5 Arthur Dove, quoted in Samuel Kootz, Modern American Painters (New York: Brewer and Warren, 1930), 37.

6 Alfred Stieglitz, quoted in Swift, 48.

7 Arthur Dove, “An Idea,” in Arthur G. Dove: Paintings, exh. cat. (New York: Intimate Gallery, 1927), n.p.

8 John Edgar Chamberlain, “Pattern-Paintings by A. G. Dove,” Evening Mail (New York), March 2, 1912; reprinted in “Photo-Secession Notes,” Camera Work, no. 38 (April 1912): 44.

9 Arthur Dove, quoted in H. Effa Webster, “Artist Dove Paints Rhythms of Color,” Chicago Examiner, March 15, 1912, 12.

10 See Debra Bricker Balken, “Continuities and Digressions in the Work of Arthur Dove from 1907 to 1933,” in Arthur Dove: A Retrospective, exh. cat., ed. Balken (Andover, Mass.: Addison Gallery of American Art; and Cambridge, Mass.: The MIT Press, 1997), 22.

11 Sherwood Anderson to Arthur Dove, late 1921, Sherwood Anderson Papers, Newberry Library, Chicago.

12 Paul Rosenfeld, “American Painting,” The Dial, no. 71 (December 1921): 665.

13 Elizabeth McCausland, “Dove’s Oils, Water Colors Now at American Place,” Springfield (Mass.) Sunday Union and Republican, April 22, 1934, E-6.

14 Georgia O’Keeffe, quoted in Susan Fillin Yeh, “Innovative Moderns: Arthur G. Dove and Georgia O’Keeffe,” Arts Magazine 56, no. 10 (June 1982): 69.

Arthur Dove in Paris, 1908–09

Arthur Dove in Paris, 1908–09

In May of 1908, Dove sailed for France with his first wife Florence Dorsey, a former neighbor from Geneva, New York where he had grown up as a child. Prior to this date, he had worked as a successful illustrator in Manhattan where he carved out a career producing line drawings and cartoons of topical subjects for publications such as McClure’s, Century, and Scribner’s. However, Dove soon tired of the medium, finding little opportunity to deviate from the thematic requirements of his patrons. Illustration was too bound to the figure, he reckoned. Moreover, as a child he had exhibited a deep propensity for nature.

As a sideline, he tried his hand at painting where he could better exercise his independence and creativity. The diversion, as it turns out, would soon become a life-long occupation.

Dove lived in France for almost fifteen months where he took to both the environs of Paris and the coastal regions of the Mediterranean such as Cagnessur-Mer to paint. There, he produced landscapes that are sun-drenched and comprised of fluid, loose brushstrokes that elaborated on late Impressionist techniques where subject matter is dissolved into the surrounding atmosphere.

As such, they represent a significant advance over the more clumsy, less assured

cityscapes that Dove painted in New York, revealing that his European sojourn had resulted in new-found pictorial authority.

Upon his return to Manhattan in late 1909, Dove was eager to continue to paint full-time. Yet, he was momentarily forced back into the marketplace for illustration even though it failed to satisfy him aesthetically. As he later wrote, “In France . . . I was free . . . Then back to America and discovered that at that time it was not possible to live by modern art alone.”

Landscape, 1908–09

France had been a liberating experience for Dove. Still, upon his return to the United States in 1909, he spent time in Upstate New York in the Finger Lakes region where he had been raised to assess the stylistic approaches that he had adopted such as Post-Impressionism. He knew that his output abroad did not stack up with current avant-garde tactics pursued by the likes of Henri Matisse and Pablo Picasso. In one of the most dramatic reversals in modernist art, Dove subsequently painted six small “abstractions,” as he dubbed them, that forged new aesthetic territory by abruptly countering the “dead end” he thought his luminous paintings of the French countryside represented. These small compositions forgo image-making entirely by focusing on the nature of light itself and the chromatic features that saturate landscape.

Helen Torr, an artist who met Dove in the late 1910s, and who subsequently became his second wife, later reminisced on the origins of the new pictorial direction that settled in his work, noting that he “lived in the woods . . . for some months working on three color theory. He tore bark off the trees, pulled up plants by the roots, always finding three colors (in different intensities, of course) in the roots, bark, flowers and leaves, birds and butterflies.” As a result,

Dove embarked on a life-long project that involved, as he put it, the revelation of the “sensations of light from within and without” that suffuse nature’s holdings. Radical, unprecedented visual statements, these paintings represent the first abstractions made by an artist in the United States.

Abstraction No. 1, 1910–11

Abstraction No. 4, 1910–11

Abstraction No. 6, 1910–11

Abstraction, 1914–17

That Dove made the leap into abstract painting around 1910–11 with little build-up or foreshadowing in his painting has been the subject of speculation. How did he relinquish late Impressionist techniques that emphasized bright, liquid brushwork, and idyllic agrarian settings in favor of more pondered studies of nature that grew from an analysis of color and quasi-scientific investigation? Part of any retelling of Dove’s reconceived project incorporates his new dealer and patron Alfred Stieglitz, who operated the 291 gallery, named for its address on Fifth Avenue in New York, and which operated from 1903 to 1917.

Dove met Stieglitz shortly after his return to the United States in 1909. The encounter occasioned an instantaneous affinity that was sustained over a lifetime. In Stieglitz, Dove located a patriarchal figure whose aesthetic program would eventually include American artists such as John Marin, Georgia

O’Keeffe, and Paul Strand while forgoing Europeans such as Henri Matisse, Pablo Picasso, and Auguste Rodin, who had once been part of his stable. By 1917, Stieglitz’s commitment to homegrown radicals who stretched the formal parameters of modernism was total: he embarked on a mission to tout the unique traits and originality of American vanguard art. It was most likely Stieglitz who

Abstraction Untitled, c. 1917–20

encouraged Dove’s daring break with representational imagery, that is, to surpass his earlier derivations of French painting.

In advance of his first solo exhibition at 291 in 1912, Dove gave up illustration, and a lucrative occupation, to live in Westport, Connecticut were he supported himself and family as a chicken farmer. However, the demands to make ends meet were daunting and his output as an artist drastically dwindled. By 1917, his sole artistic excursions consisted of drawings in charcoal that probed his avowed interest in disclosing the “sensations of light from within and without.”

Despite the perpetual setbacks that he experienced as a farmer, Dove became integrated into a vibrant community of intellectuals in Westport. These figures included some of the foremost writers of the early twentieth century, such as Sherwood Anderson, Van Wyck Brooks, and Paul Rosenfeld, in addition to artists such as John Marin and Paul Strand. Their conversations frequently centered on the intrinsic or defining aspects of American culture and its differentiation from European modernist expressions: a prevalent feature of contemporary literary discourse. Both Anderson and Rosenfeld, moreover, located a matchless sensibility in Dove’s painting that countered perceived notions that American art was dependent upon formal experimentation that emanated from Paris. They were also profoundly disaffected of the new invasion of the machine within American culture and the mechanized subjects adopted by contemporary artists such as Marcel Duchamp (who lived and worked intermittently in New York as of 1915) and May Ray. Nature, they believed, propounded the only means for the revelation of the artist’s subjectivity.

By 1921, Dove would renew his commitment to painting, and during this year, Anderson wrote to him, “There is some faint promise of rebirth in AmeriRiver Bottom, Silver, Ochre,

Carmine, Green, c. 1923

can art but . . . to be real the flesh must come in. I suppose, I have since seeing your piece of work, looked to you as the American painter with the greatest potential for me.” At the same time, Rosenfeld, who wrote for publications such as The Dial, a prominent literary magazine founded by the Transcendentalists in 1840, noted that Dove’s work exerted a certain “male vitality,” suggesting that Dove’s masculinity imprinted his renditions of the generative forces of nature. While Dove’s paintings would enact some of this interpretation, especially its phallic adumbrations, he remained equally committed to forging unforeseen stylistic languages.

Penetration, 1924

Colored Drawing, Canvas, 1929

Colored Drawing, Canvas, 1929

During the decade of the 1920s, Dove not only renewed his allegiance to modernist painting, but he left Westport, Connecticut and became involved with Helen Torr, an artist whose aesthetic thinking was aligned with his. Commencing in 1923, they made their intermittent home and studio on a fortytwo-foot yawl christened the Mona. Frequently docked in Halesite, a hamlet on an inlet on Long Island Sound near Huntington and Lloyd Harbor, the site yielded some of Dove’s boldest pictorial statements. Not only is his work of this decade typified by an upbeat sensuality that stems from his ongoing study of light and the ephemeral dimensions of nature, but his subjectivity pervades these ebullient paintings. No wonder that one critic, Henry McBride, would later announce that Dove’s entire corpus of work represented the fulfilment of transcendentalism that crested with Walt Whitman and Herman Melville.

In 1925, as he began to actively exhibit in frequent juxtaposition with Charles Demuth, Marsden Hartley, John Marin, and Georgia O’Keeffe, he wrote a poem—his preferred literary form—that he titled “A Way to Look at Things.” One section reads: “There is much to be done—/Works of nature are abstract./ They do not lean on other things for meaning.” That Dove spurned figuration in

his abstractions of flora and the diurnal passages of the sun and the moon was reinforced in a subsequent declaration, whereby he averred, “WHY NOT MAKE THINGS LOOK LIKE NATURE? BECAUSE I DO NOT CONSIDER THAT IMPORTANT.” In these emphatic pronouncements, Dove makes clear that nature alone provided the ultimate source for experimentation.

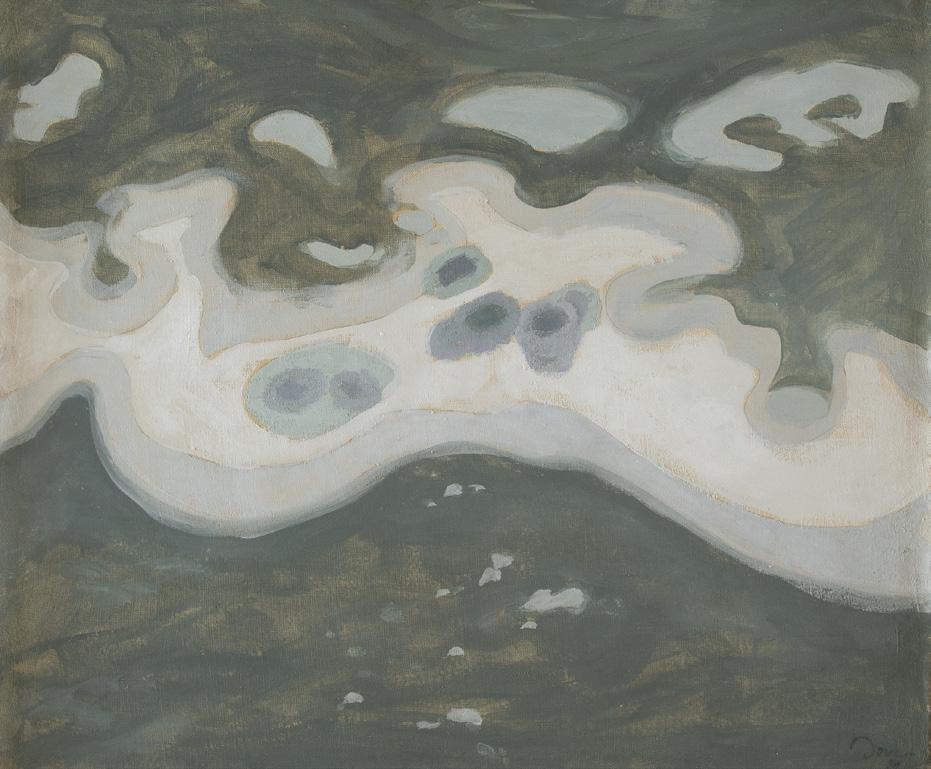

Snow on Ice, Huntington Harbor, 1930

Snow on Ice, Huntington Harbor, 1930

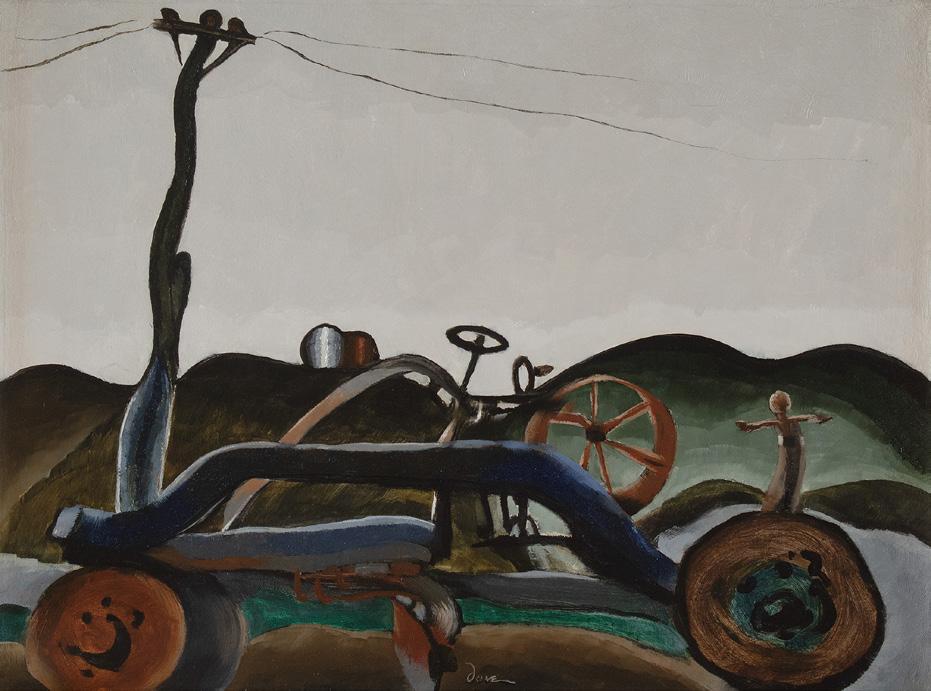

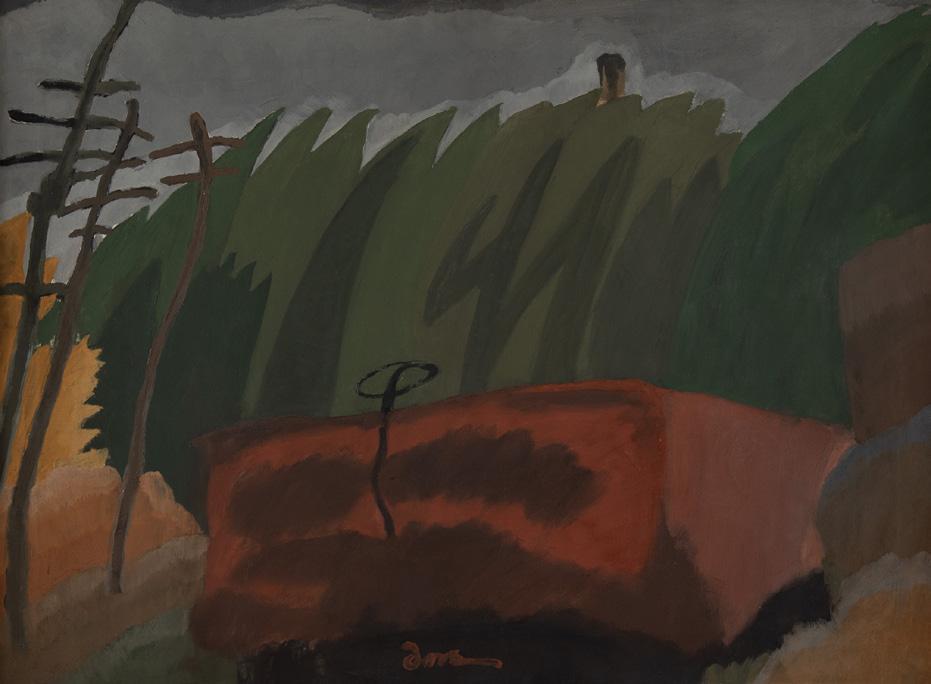

While nature was always Dove’s primary subject, he was also drawn intermittently to mechanical and architectonic forms. During the 1920s and early ’30s, especially, he painted numerous images of lanterns, gears, water mills, barges, telegraph poles, scraping machines, freight cars, and storage tanks that seemingly counter his stock inventory of natural forms. However, unlike the work of many of his contemporaries such as Marcel Duchamp—who was an omnipresent fixture of the New York avant-garde as of 1915—and American modernists such as Morton Schamberg, Dove approached these technological devices as objects of beauty that could yield to infinite abstraction rather than as deadpan, ironical representations of the commodities that issued from mass-production. Mining the absurdity of mechanized contraptions and their domestic offshoots was never Dove’s gameplan as it was for Duchamp whose aesthetic pranks and irreverence for modernism’s core investment in ingenuity augured the Dadaist movement internationally.

Dove’s allusions to industry in his work always co-exist in relationship to nature. Part of their transformation is realized by the pervasiveness of warm, saturated light, his ongoing visual conceit. This process of idealization was one that he shared with his friend Georgia O’Keeffe whose pictorial responses to the built

environment of New York and its new towering structures in the mid-1920s are fused with celestial orbs.

During the early 1930s, as Regionalism made inroads in American art in open distain of the modernist movement, and narrative painting made a comeback, writer Elizabeth McCausland, who would become one of Dove’s primary critical advocates during the Great Depression, noted that “He does not paint the American Scene.” What she meant, was that Dove was never drawn to mundane subjects, that natural phenomena and all of its transcendent possibilities remained his domain.

Town Scraper, 1933

Untitled (Coal Carrier), 1930

Coal Carrier II, 1930

Study for Cinder Barge and Derrick, 1931

Study for Cinder Barge and Derrick, 1931

Cinder Barge and Derrick, 1931

Cinder Barge and Derrick, 1931

Sunday, 1932

Alfred Stieglitz had been forced to close his 291 gallery in 1917, no longer able to maintain the rent and upkeep on the space. However, he never became inactive as a dealer: in the early 1920s, he staged exhibitions of American modernist art at the Anderson Galleries, an auction house located on Park Avenue. Thereafter, in 1925, he opened another showcase in the same building that he named the Intimate Gallery, a small space which he operated for four years until 1929 when he relocated to Madison Avenue and founded An American Place where he winnowed his stable of artists to Dove, John Marin, and Georgia

O’Keeffe. The “Place,” as it was affectionately known, with its austere white walls and no seating, set a new standard for subsequent exhibition spaces in New York, reinforcing that advanced or progressive vanguard art required deep reflection and looking, that its architectural confines had to be neutral.

Not only did Stieglitz’s last two ventures provide Dove with solo shows on an almost annual basis until his death in 1946, but they also secured his weight and reputation as the foremost abstract artist to emerge in the United States in the early twentieth century. In 1929, just as Stieglitz opened the Place, Dove wrote that he was “more interested now than ever in doing things about

things: pure paintings seem to stand out from those related too closely to what the eyes see there.” By that he meant, paring his pictorial elements to more simplified shapes that captured the innate dynamism of nature, such as the rise of the sun at dawn or its transit with the moon above the earth.

Three in a Boat, 1936

Three in a Boat, 1936

In 1933, Dove and Helen Torr returned to Dove’s family home in Geneva, New York for what amounted to a five-year stay. Despite his love of the water and sailing the Mona on Long Island Sound, the maintenance of the yawl had become prohibitive. Dove’s economic life had always been fragile but with the onset of the Great Depression there were even fewer sales for his painting. When his mother died in January of 1933, he and Torr sold their few effects and decamped to the family farm where they grappled with unforeseen back taxes and liens on the property. Prior to their departure, Dove conveyed to Stieglitz, “There is something terrible about ‘Up State’ to me…It is like walking on the bottom of water.” Dove’s parents had all but disinherited him given his chosen vocation as an artist; returning home was viewed as a setback whatever the financial necessity.

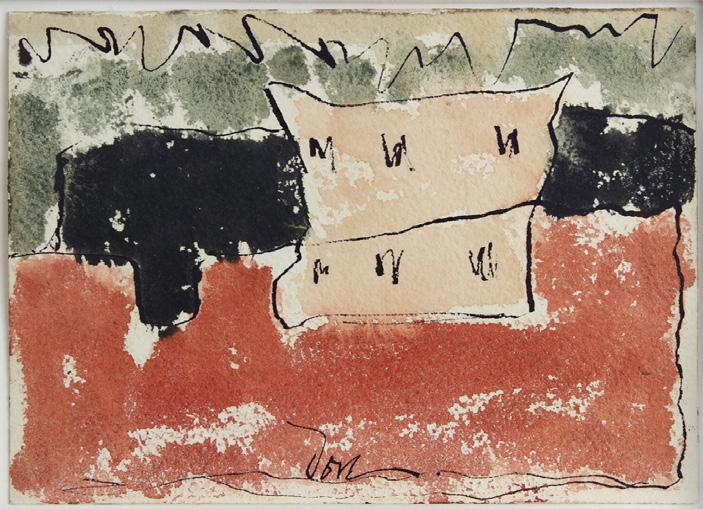

Still, Dove’s time as an artist in Geneva was prolific. He produced there some of his most jubilant, uplifting hymns to nature as well as occasional abstractions of industrial structures such as silos, flour mills, power plants, and bridges, in addition to farm implements, barns, and sheds. He also began to work more frequently in series by expounding on the increasingly spare, reductive shapes that now populated his universe of forms. Of this development, that purposefully eliminated any

reference to known, identifiable imagery, Dove wrote to Stieglitz in 1938 that his paintings “have more bite than last year, naturally. Life must have more than just the beautiful.” The pronouncement—an iteration of earlier statements—denotes that the ongoing thrust of his work pivoted on compositional invention rather than picturesque subjects.

Willow Tree, 1938

By mid-1938, Dove and Helen Torr were able to move back to the north shore of Long Island where they settled in a one room former post office in Centerport near Huntington. The small abode became Dove’s final home and studio. With the burdens of his family estate resolved, he resumed life on the Sound, albeit without a sailing boat such as the Mona. And, while his back porch had ample views of the inlet where he sat each day to take in the “sexy” wildlife, as he dubbed it, his work became increasingly more inward and more cerebral.

Prior to this date, Dove’s work, however abstract, was rooted in observation, especially of the cyclical rhythms of nature and their evanescent, luminous dimensions. Hence, his continuing upbeat revelations or depictions of the “sensations” of light and their animation of the landscape. Dove’s years in Centerport, however, were beleaguered by illness. Not only was he initially setback by pneumonia from which it took him months to recover, but also from a weak heart and a chronic kidney condition that kept him frequently bedridden. No matter his love of sailing; his earlier life on the Mona, particularly during the winter months, had caught up with him and taken its toll on his health.

In Centerport, Dove abandoned his early repertoire of natural referents for non-objective painting that was given, as he stated to “design arrangements” that have no analogies in the material world. They grew, that is, from pondering the ways to build composition through combinations of organic and quasi-geometric shapes that could be filled with resplendent color. His overall ambition became “to weave the whole into a sequence of formations rather than to form an arrangement of facts.” These audacious forays into unchartered aesthetic territory, at once rhythmic and lyrical, forecast some of the preoccupations of artists associated with the midcentury movement known as Abstract Expressionism or the New York School.

Green and Brown, 1945

Untitled #10, 1941

Untitled #11, c. 1941

Untitled #11, c. 1941

Untitled [5–30–42], 1942

Untitled [6–11–42], 1942

Untitled [6–3–42], 1942

Untitled (Sea and Sand), 1943

Moon, 1935

watercolor on paper

7 x 5 inches

Private Collection

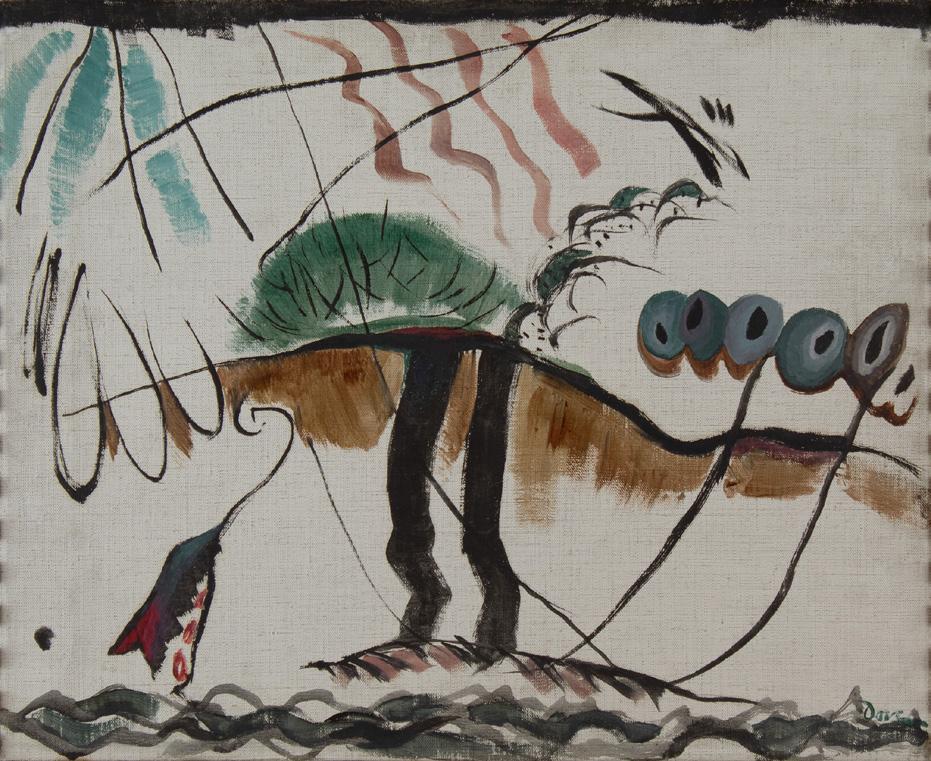

Tempera, 1938

tempera on board

5 x 7 inches

Private Collection

Landscape, 1908–09

oil on canvas

18¼ x 21½ inches

Private Collection

Abstraction No. 1, 1910–11

oil on panel

8¾ x 10½ inches

Private Collection

Abstraction No. 4, 1910–11

oil on panel

8 3/8 x 10½ inches

Private Collection

Abstraction No. 6, 1910–11

oil on panel

8 3/8 x 10½ inches

Private Collection

Abstraction, 1914–17

oil on canvas

18 x 22 inches

Private Collection

Abstraction Untitled, c. 1917–20

charcoal on paper

20½ x 17½ inches

Collection of Michael and Juliet Rubenstein.

Promised gift to The Metropolitan Museum of Art

River Bottom, Silver, Ochre, Carmine, Green, c. 1923

oil and metallic paint on canvas

24 x 18 inches

Private Collection, courtesy Agnews Gallery, London

Penetration, 1924

oil on panel

22 x 18⅛ inches

The Jan T. and Marica Vilcek Collection.

Promised gift to The Vilcek Foundation

Colored Drawing, Canvas, 1929

oil on canvas

18 x 22 inches

The Vilcek Foundation

Sun on the Water, 1929 oil, metallic paint and charcoal on paper mounted on bristol board

15 x 19½ inches

Private Collection

Untitled, c. 1929 oil on metal

28 x 20 inches

The Jan T. and Marica Vilcek Collection.

Promised gift to The Vilcek Foundation

Silver Log, 1928 oil on canvas

30 x 18 inches

Private Collection

Snow on Ice, Huntington Harbor, 1930 oil on canvas

18 x 21 inches

Private Collection

Town Scraper, 1933 oil on canvas

18 x 24 inches

Private Collection

Untitled (Coal Carrier), 1930

gouache on wove paper

3¾ x 4½ inches

Terry Dintenfass, Inc., New York

Coal Carrier II, 1930

oil on canvas

10 x 20 inches

Private Collection

Study for Cinder Barge and Derrick, 1931 charcoal, graphite and watercolor

5 x 7 inches

Private Collection

Cinder Barge and Derrick, 1931

oil on canvas

22 x 30 inches

Private Collection

Freight Car II, 1938

watercolor and ink on paper

5 x 7 inches

Private Collection

Freight Car, 1937

oil on canvas

20 x 28 inches

Private Collection

Sunday, 1932 oil on Masonite

15 x 19½ inches

Private Collection

Dawn I, 1932 oil on canvas

22 x 22 inches

Private Collection

Sun and Moon, 1932 oil on canvas

18½ x 22 inches

Private Collection

Three in a Boat, 1936

watercolor on paper

5 x 7 inches

Private Collection

Willow Tree, 1938

watercolor on paper

4⅞ x 6⅞ inches

Private Collection

Formation II, 1942 oil on canvas

24 x 32 inches

Private Collection

Polygons and Textures, 1943–44 oil on canvas

23¾ x 31¾ inches

Private Collection

Green and Brown, 1945 oil on canvas

18 x 24 inches

Private Collection

Partly Cloudy, 1941

watercolor and pencil on paper

5½ x 4 inches

Private Collection

Untitled #10, 1941

watercolor and ink on paper

5 x 7 inches

Private Collection

Untitled #11, c. 1941

watercolor and ink on paper

5 x 7 inches

Private Collection

Sunrise I (Set of Three), c. 1941

graphite, ink and watercolor on paper

4 x 5½ inches

Private Collection

Sunrise III (Set of Three), c. 1941

graphite, ink and watercolor on paper

4 x 5½ inches

Private Collection

Sunrise II (Set of Three), c. 1941

graphite, ink and watercolor on paper

4 x 5½ inches

Private Collection

Untitled [5–30–42], 1942

watercolor and ink on paper

3 x 4 inches

Terry Dintenfass, Inc., New York

Untitled [6–11–42], 1942 watercolor and ink on paper

3 x 4 inches

Terry Dintenfass, Inc., New York

Untitled [6–3–42], 1942 watercolor and ink on paper

3 x 4 inches

Terry Dintenfass, Inc., New York

Untitled, c. 1942 gouache on card

3 x 4 inches

Terry Dintenfass, Inc., New York

Untitled (Sea and Sand), 1943 mixed media

3 x 4 inches

Terry Dintenfass, Inc., New York

This catalogue is published on the occasion of the exhibition “Arthur Dove: Sensations of Light” on view from April 22 through May 25, 2023 at 25 East 73rd Street, New York 1001.

An expanded printed catalouge will be available from the gallery in June. Please contact the gallery for details.

Cover detail: Sun and Moon, 1932

Catalogue © Alexandre Fine Art Inc.

Photography © Alexandre Fine Art Inc.

Photography: Maria Stabio

Photographic Production: Maria Stabio

Editorial Production: Emma Crumbley

Design: Lawrence Sunden, Inc., Harrington Park, New Jersey

The exhibition is organized to celebrate Balken’s recently published Arthur Dove: A Catalogue Raisonné of Paintings and Things, distributed by Yale University Press in 2021. The catalogue raisonné—a key resource for this exhibition surveys the artist’s known paintings and assemblages, or “things,” alongside an incisive essay on his work’s critical reception, an illustrated chronology, and an extensive bibliography and exhibition history. Balken was the lead curator of the most recent Dove retrospective co-organized by the Addison Gallery of American Art and The Phillips Collection, which traveled to the Whitney Museum of American Art in 1998. On the occasion of this exhibition, Balken has contributed ten new short essays on various aspects of Dove’s career, which will be the basis for an exhibition catalogue published by the gallery.

No portion of this catalogue, images or text may be reproduced, either in printed or electronic form, without the expressed written permission of the gallery.