31 minute read

SPECIAL REPORT GBCSA CONVENTION 2020: NEAR POSSIBLE The GBCSA 2020 conference speakers articulate their perspectives on how to map the path to a sustainable built future

CONVENTION 2020: NEAR POSSIBLE

GBCSA CEO, Lisa Reynolds, says the time is now to develop a clear roadmap and an ambitious action plan towards a sustainable future. In this special report, +Impact uncovers green building thought leadership shared by the GBCSA 2020 conference speakers who explore and articulate their international perspective on how to decisively transition to a built environment on which people and planet thrive.

Advertisement

WORDS Mary Anne Constable

REGENERATIVE DESIGN: CONNECTING PEOPLE AND NATURE TO REVERSE CLIMATE CHANGE

AMANDA STURGEON Head of Regenerative Design, Mott MacDonald, Australia

What are your thoughts on developing a sustainable roadmap from a built environment perspective?

AS: We have known for decades that our buildings need to take a different course to reduce their impact on Challenge, Living Community Challenge and Living

climate change, biodiversity loss and the overall health of our planet, but we have made only small steps and our buildings are nowhere close to reaching the zero carbon targets that many cities around the world have adopted. A roadmap is much needed and overdue.

What does regenerative design mean to you?

AS: Regenerative design is about making positive during the day than they did in a standard office building.

impacts ecologically and socially with the buildings and communities that we design. Rather than reducing the impact of buildings, regenerative design is a design approach that starts right at the beginning of a project to identify how rejuvenating the ecology, culture and community of the specific place inform the design.

What kind of resistance have you come up against the concept of regenerative design during your career, and how have you overcome it?

AS: Regenerative design requires a systems-thinking approach that puts nature and ecology at the forefront of the design process. Typically, nature is not a consideration in the design of the project – it is ignored, or worse, destroyed completely. Many people have lost their connection to nature – they see money and economy and prestige as the only driving forces for creating a building and therefore too often economics are used as an excuse to not take a regenerative design approach. I also see pushback from design teams and clients who are only able to think about one issue at a time rather than the interconnectedness of every decision that we make, that is the way they have been trained to work. Connecting people to nature – reminding them of their childhood connections and the peace and tranquillity that they interconnectedness of the world’s ecosystems. We also

feel when immersed in nature has been successful for me in the past.

What are the most significant changes and transformations you have seen in attitudes towards regenerative design in your career?

we are at a critical time in our world, with so much of our biodiversity extinguished and climate change impacts becoming even more evident, more people are looking for ways to scale change rapidly. They are realising that creating buildings the same way as we have always done will not work, we need a different design process to create the radical change we need.

Describe a couple of examples of your work, which exemplify the principles of regenerative design.

AS: My career over the past decade has focused on creating programmes, awareness and education around regenerative thinking, for example, the Living Building Product Challenge programmes.

How have behaviours and attitudes changed during Covid-19? How do you think Covid-19 will mould things going forward?

AS: With many people working from home, they have become more connected to their families, their communities, and have had better access to the outside They have also had time saved from commuting and have been forced to slow down and face the stresses in their lives. I think people will want to maintain their connection to the outside, more time for themselves and their families and less travel into the future.

How has technology influenced regenerative design?

AS: Technology has helped us to understand the AS: I have noticed that people are acknowledging that

have access to the science that shows how the world is changing – there is no excuse to be blind to it and to carry on business as usual.

What is the key takeaway you would like people to gain from your keynote presentation?

AS: That we need to scale a different way of creating our buildings urgently.

JOHN ELKINGTON Co-Founder and Chief Pollinator at Volans, United Kingdom

What are your thoughts on developing a sustainable roadmap for our society to follow?

JE: There is no question that clear and well-supported roadmaps can drive change, but I am not sure that a lack of roadmaps is our main problem now. Our main problem is a lack of political will. And in a period of populism, even with all its increasingly obvious defects, science, goals and roadmaps are often treated as playthings, to be kicked around and discarded. To see populist leaders respond to the climate chaos of recent years (“it will get cooler”) is almost to despair of politics and of humanity. But you could also see such extremes as the last, desperate resistance of an old, unsustainable order that is dying.

What are the founding principles of sustainability

JE: At its simplest, to leave both the planet and our human world better off than we found them. That was the message in my Triple Bottom Line (TBL) agenda introduced back in 1994, followed up in 1995 with People, Planet & Profit. Sadly, over time the sustainability agenda has been misinterpreted as an incremental change rather than a system change agenda – as a nice-to-have agenda rather than as an existential requirement. The Sustainable Development Goals are an exponential change agenda rather than about incremental change, as too many people currently perceive them.

You’ve been described as the “Godfather of Sustainability”. What kind of resistance have you come up against the principles [stated earlier] during your career, and how have you overcome it?

JE: Since I have been working in this field, I have come up against pretty much every form of resistance known to man, short of imprisonment or assassination. I have been sued by ICI and McDonald’s, I have been attacked in the media, and I have been blocked in boardrooms. But overall, our agenda has gone from strength to strength. And the way in which business leaders think about all this has gone from “they’re really Communists” to “with Walmart now committing to regeneration, how can we catch up – and possibly

that you aspire to?

even overtake?”

Please tell us about Green Swans.

JE: All our work on corporate responsibility over the decades has been useful, foundational indeed but as our economic, social, environmental and governance systems begin to unravel, a process accelerated by the Covid-19 pandemic, resilience has shot up priority lists both in the public and private sectors. And the only way to ensure long-term resilience is to invest in the regeneration of such systems. This is the theme of my twentieth book, Green Swans: The Coming Boom in Regenerative Capitalism, published in April this year, by Fast Company Press.

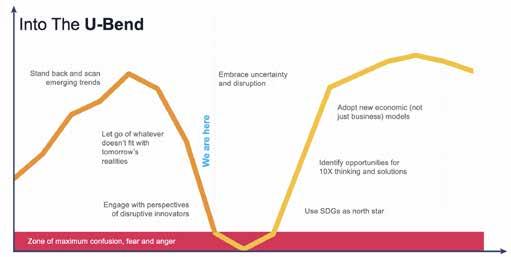

The first diagram in the book [shown on page 23] is one I had been using for a couple of years before Covid-19 hit arguing that the global economy’s bull run was masking a much deeper set of discontinuities. The bar at the bottom is where ordinary people experience the greatest confusion, fear and anger. If this analysis is anywhere near accurate, the era of populism is far from over.

Readers will not be surprised to learn that the Green Swan concept was informed by the “Black Swan”, one of the most successful memes of the past decade. Introduced by Nassim Nicholas Taleb in his 2007 book, The Black Swan, the concept spotlights events that take us totally by surprise, that have an off-thescale impact, and that we fail to understand afterwards – setting ourselves up to fail again. Interestingly, Taleb says Covid-19 is not a Black Swan – because we saw it coming but too many leaders failed to act.

By contrast, if most Black Swans take us exponentially to places we really do not want to go, my definition of a Green Swan embraces a profound market shift, generally catalysed by some combination of Black or Gray Swan (foreseen) challenges and changing paradigms, values, mindsets, politics, policies, technologies, business models, and other key factors. The link back to the TBL agenda is that a Green Swan delivers exponential progress in the form of economic, social, and environmental wealth creation.

In the book, I also talk about “Ugly Ducklings”, drawing on the fairy tale by Hans Christian Andersen. These are early-stage concepts, mindsets, technologies, or ventures with the potential to drive either Black Swan (driven by bad exponentials) or Green Swan (driven by good exponentials) market trends. For me, a potential Green Swan is the European Commission’s growing linking of its recovery plan with its Green Deal objectives.

The potential future evolution of an Ugly Duckling can be hard to detect early on, unless you know what you are looking for. Tomorrow’s breakthrough solutions often look seriously weird today. The net result is that we give them significantly less attention and resources than they need – or than the future of the 2030s and beyond would want us to, in hindsight.

Tell us about the shift in approach from responsibility to resilience and regeneration. How does that look in society today? How would you like to see this shift happen and what can we do better?

JE: The ‘3Ps’ of the Triple Bottom Line became central to the sustainable business debate from their launch in 1995. When we did the product recall of the TBL in 2018, we began the Tomorrow’s Capitalism Inquiry. One emergent framing was the ‘3Rs’, which emerged from the production of our new book, Green Swans: The Coming Boom in Regenerative Capitalism.

When the urgency is clear enough, people do act – though the continuing unwillingness of populist leaders to act on the climate emergency is a severe test for anyone who believes in human rationality.

The 3Rs are: Responsibility, Resilience and Regeneration. As we dug deeper, it became clear that almost all business effort in pursuit of sustainability had focused to date on the Responsibility agenda. • Responsibility: Typical platforms in this area have included the EcoVadis, GRI, IIRC, SASB and

WBCSD. Key activities have focused on voluntary standards encouraging greater transparency and accountability, stakeholder engagement, supply chain management and investor engagement. • Resilience: Unfortunately, all this effort has failed to head off a growing number of “wicked problems”, at the outer edge of which we see the

Black Swans spotlighted by Nassim Nicholas

Taleb. The Covid-19 outbreak is one such Black

Swan. Resilience activities include China’s growing number of “sponge cities”. Wuhan, which led in this field, has now signalled the need for very different forms of resilience. • Regeneration: The change agenda for Green

Swans requires a massive shift in thinking and investment, towards the regeneration of our economies, societies and environment. Among the new networks emerging in this space are those based on The Capital Institute (whose CEO, John

Fullerton, did the first Tomorrow’s Capitalism lecture at our Tomorrow’s Capitalism Forum on 10

January 2020), Eden Project International (whose founder, Sir Tim Smit, won one of the first pair of Green Swan Awards), the Alan Savory Institute and The Regenerators.

How have behaviours and attitudes changed during Covid-19? How do you think Covid-19 will mould the way forward?

JE: I chaired a conference session this autumn with several panellists who are CEOs of major financial institutions. One of them noted that things – and behavioural changes – that would have been unthinkable even last year have become possible, even inevitable, in 2020. When the urgency is clear enough, people do act – though the continuing unwillingness of populist leaders to act on the climate emergency in places like Australia, Brazil and the USA is a severe test for anyone who believes in human rationality.

What is the key takeaway you would like people to gain from your keynote presentation?

JE: I was originally trained as a city planner – and continue to find cities, urban regions and the built environment fascinating. And they are also where most of our species now lives, so putting our cities onto a very much more sustainable path is make-or-break for the future of our species – and all other species.

DESIGN WITH LOVE: ARCHITECTURE FOR JUSTICE AND HUMAN DIGNITY

KATIE SWENSON Senior Principal, MASS Design Group, United States

What are your thoughts on developing a sustainable roadmap from a built environment as well as an urban and cities’ perspective?

KS: The last six months of the global pandemic have revealed how interconnected we are, and how difficult it is currently for people to thrive, and for our planet to support human life. We cannot breathe freely, literally. In this pandemic, we are united by our global interconnectedness, and this conference brings out the best of that – we get to share in inspiration and commitments, to share in ideas and to craft a plan together. That said, a critical part of our plan must involve an emphasis on the local sourcing and production of buildings, using local labour, artisanship and creativity.

Architecture is never sustainable: it is either climate negative or climate positive. At MASS Design Group, in order to move our buildings toward climate positivity, we try to adopt a “Lo-Fab” building approach. Local Fabrication (Lo-Fab) is the practice of creating value through the construction process as much as the finished building itself. Lo-Fab is a commitment to supporting the local economy using local contractors and locallysourced materials – highlighting local innovation and ideas, bolstering and developing local craftsmanship, hiring local labour, and investing in local capacity building and job training. Through this focus on locallysourced material and labour, we can leverage the entire supply chain, minimising the environmental impact, and assuring that the majority of capital invested in construction flows to the community we are serving.

A good example of our Lo-Fab process in practice is the design and construction of The Rwandan Institute of Conservation Agriculture (RICA) in Bugesera, Rwanda. RICA’s mission is to train the next generation of leaders in conservation agriculture to attain healthy and sustainable food independence in Rwanda. The campus features innovative methods of power generation, water use, and green infrastructure, and is estimated to be carbon-positive by the 2040s. It has begun to achieve this by reducing the embodied carbon of the buildings, sourcing 96% of materials by weight from Rwanda, installing a 100% off-grid solar farm, sourcing and treating all water on-site, and offsetting the remainder carbon by restoring parts of the savannah woodland and reforesting key areas within the campus.

Design with Love: At Home in America Cover

Harry Connolly

What are the founding principles that you believe each design should aspire to? Please use examples of your work to illustrate this.

KS: MASS Design Group is a design collective dedicated to delivering architecture that promotes justice and human dignity. We were founded on the idea that architecture is never neutral; it either hurts or it heals.

Twelve years ago, MASS Design Group designed and built the Butaro District Hospital in northern Rwanda, an area where 400 000 people were not served by any medica; facility, and in an environment where many healthcare facilities lacked the necessary precautions to prevent the transmission of disease. Hospitals often had small, poorly ventilated waiting rooms in which a patient with an injury, such as a broken leg, would be waiting in proximity to a patient with Tuberculosis. Here, architecture and spatial care protocols were directly putting people at risk.

Butaro is a beautiful, medically-sound facility, with natural light, wide hallways, courtyards, and spaces for families to gather, oriented to take advantage of the beauty of this mountainous region. Thanks to projects like these and other investments in health infrastructure in Rwanda, average life expectancy has gone from less than 30 years to almost 70 over the last three decades.

I came to MASS to bring these same core principles – that our buildings should improve our health and wellbeing – to the design of homes that are affordable to people with low incomes. And that design happens locally, where residents are expert in community needs and stakeholders can work together to create the vision for a project.

The J.J. Carroll Apartments redevelopment project in Brighton, Mass., designed in partnership with 2Life Communities, a non-profit organisation dedicated to developing and managing safe, affordable, and dignified housing for older adults, is one such project. The current J.J. Carroll buildings, built in 1966, are a series of two-story brick townhouses right next door to 2Life’s Brighton campus buildings, with 64 units for an aging and disabled community. The development is now past its useful life and lacks the accessible design features required by residents with various physical abilities and ages.

When MASS Design Group began work with 2Life, designers hosted a workshop series with current J.J. Carroll residents to learn how they operate, what they most want in the new development, and how the design could best support 2Life’s goal to offer older adults the chance to thrive in a dynamic, supportive environment. At the top of everyone’s list was community. Loneliness and social isolation are two of the top health hazards

Iwan Baan Butaro District Hospital

for aging adults, associated with a variety of poor mental and physical health outcomes and a higher risk of mortality overall.

Covid-19, however, dramatically increased the urgency for thoughtful design to keep people safe, while creating opportunities for social interaction. People 65 years or older represent 80% of all deaths from Covid-19, but older adults also need to balance another threat to their health – social isolation.

Building on community feedback about what was most loved about J.J. Carroll – its neighbourliness – the design team came up with an approach to maintain this type of intimate connection and community while increasing the capacity to more than double the units on site. We created a series of “neighbourhoods” made up of apartment clusters of between five to eight units each, allowing residents to “pod” in smaller groups, while also enjoying a diversity of spaces and access to green space, views, natural light and ventilation.

MASS Design Group

Gun Violence Memorial Project

Over the past six months, MASS has created a series of guides that suggest how we can design buildings that make us healthier. Like Butaro did for doctors, patients and visitors, we can design non-medical environments – housing, schools, restaurants, offices and outdoor spaces – to prioritise user health, but not at the expense of their wellbeing.

How can one incorporate justice and human dignity into design and what does this really mean?

KS: To design with dignity, and for justice, is to bring one’s whole self to the understand the broadest implications of the work at hand, to consider the conditions which make design needed, to understand the ambitions of those partnered in the design process, to strive for the mission of the design of the project to guide its process, product and long-term outcome.

Justice and dignity must be fought for. In the U.S., we are confronting the power of memorials in the construction of public memory and identity, especially as we encounter the plethora of memorials dedicated to white supremacy. With the design of the National Memorial for Peace and Justice, we learned, among so many things, the power of truth telling, and creating space for truth and reconciliation to take place, in ways both intimate and collective.

Our Gun Violence Memorial Project collects and displays personal objects of victims of gun violence – and with them – the personal stories by those who loved them. The losses are multiplied, however, and the memorial shows the magnitude of shared loss, made more striking for its specificity. Architecture, in this case, can be healing, spatialised.

What kind of resistance have you come up against your design principles during your career, and how have you overcome it?

KS: So many of the market-based metrics for success – economic profit, gentrification of neighbourhoods, value engineering – are organised to create maximum benefit for the wealthier members of our society. I try to advocate for prioritising investing in the quality of life for people with limited means, for beautifying historically poor neighbourhoods, for providing stable and beautiful homes for everyone.

I think that resistance to these commitments is a failure of imagination. What is preventing us from creating a world where every person and family has a good home? I fear that it is a fundamental failure to care enough, or if we truly do care, then to turn that care into the policies, financial mechanisms, regulations and designs to make a more equitable society. Our systems are in fact designed, but are they designed to deliver the outcomes that we want?

How have behaviours and attitudes changed during Covid-19? How do you think Covid-19 will mould things going forward?

KS: I am optimistic about two important collective realisations we are having as a result of Covid-19.

The first is an understanding that our buildings need to do more to keep us healthy. At MASS, we believe that architecture is never neutral; it either hurts or it heals. We have learned that the design of buildings is essential to prevent the spread of infection, and that many of our contemporary building techniques which depend on mechanical ventilation can have a detrimental impact. We need to employ design for infection control principles.

The second is the realisation of the importance of home. We are all depending on our homes to be not only the places we live with our families, but also where we work, go to school, work out, perform all the facets of our lives. I hope that with this realisation will come a greater emphasis on the need for high quality homes for all people.

What is the key takeaway you would like people to gain from your keynote presentation?

KS: As design professionals, we can do so much more to create a just and sustainable world. Many of the structures of our practice orient us to participate in the perpetuation of the status quo, which is clearly taking us in the wrong direction. Breaking free is hard, leadership requires rethinking our role, and more importantly, our approach. I urge all of us to understand the true mission behind our work, and to commit to the critical work of bringing our whole selves – personally and professionally – to aspire to a world in which poverty, homelessness and racism are not tolerated.

J.J. Carroll Apartments

THE POST-COVID REVOLUTION IN THE WORKPLACE

CLIVE WILKINSON President/Design Director, Clive Wilkinson Architects, United States

What are your thoughts on developing a sustainable roadmap from a built environment as well as an urban and cities perspective?

CW: As we all know, things change very slowly in the world unless there are external forces like Covid-19 pushing change. However, it begins with some small voices crying out, and that gains momentum over time, until the voices are everywhere. At that time, people agree to change things. We still need voices to grow as the world is not yet feeling the pressure of change, but I believe that we are heading there – to a bright green world – and it is just a matter of time.

What does regenerative design mean to you?

CW: I like the phrase regenerative design – it is poetic and brings a kind of biological character to design, which in essence is just the act of drawing. Of course, it implies an ability to reconstruct itself which begs the question of what internal capacity drives the reconstruction. In my own home, I used a self-healing zinc material on the exterior – which is a kind of regenerative act.

What are the founding principles that you believe each design should aspire to? Please use examples of your work to illustrate this.

CW: Great design should touch the soul. It should also be in service to its duration of use with an appropriate use of resources. This is not to say that all design should be durable, but simply that it should devote an appropriate use of resources to its intended use. This can occasionally be a very short duration, like the structures or furnishings of an event. What touches the soul is also something that touches the earth lightly.

What kind of resistance have you come up against your design principles during your career, and how have you overcome it?

CW: The resistance we have experienced has mostly been a product of people undervaluing or not understanding the design process, which is a longstanding one. When we design, we need to have the time to mentally live in our designs, in order to develop and adjust them. We have had clients constantly change the brief on us, which is like being thrown out of bed every morning and sent to a different house. This inevitably leads to a poor outcome. A wise client once said to me, “you can’t take nine women and have a baby in one month”. He understood.

What are the most significant changes have you seen in attitudes towards transformation and sustainable design over your career?

CW: It is awesome to see how sustainability has moved from a marginal interest to a mainstream concern in architecture and design, including urban design. It is again the rise of small voices that propelled this. I don’t believe it has come full circle in addressing what we commission and construct in our cities, as there is still insufficient attention paid to adaptive re-use of the existing urban fabric. Innovative legislation could pave the way for truly prioritising the re-use of existing resources. Transformation is certainly where we are at this moment in time, as a combination of massive technological progress and a health crisis have made it impossible to return to the “old world”.

How have behaviours and attitudes changed during Covid-19? How do you think Covid-19 will mould things going forward?

CW: Covid-19 has proved something that no one could have proved before: that people can work productively from remote locations. This will change the nature of work irretrievably. The office will never be the same again. What is great is that it can finally move into the role of a community-shaped environment: a place for collective endeavours that prioritises collective work, while still accommodating private and focused needs. Hence, Covid-19 has acted as an accelerator and I think that is a good thing. I have always said that change does not happen except in a condition of stress.

What do you think the office space of the future is going to look like?

CW: Paradise. With a wealth of choice about how, where and with whom you work.

How has technology influenced workplace design?

CW: Technology is the primary driver for all change that has occurred in the workplace in the last two centuries. Most recently, the computer took over human routine work which led to the rise of the knowledge worker, and then rapid e-communications has led to true mobility in work. Since Covid-19 began, I have had some employees working remotely for long periods from Washington DC, Florida, Texas and Costa Rica!

RESPONSIBLE INVESTMENT: ENSURING A SUSTAINABLE AND RESILIENT FUTURE

SHAMEELA SOOBRAMONEY Chief Sustainability Officer, Johannesburg Stock Exchange (JSE)

What are your thoughts on developing a sustainable roadmap from a financial investment point of view? SS: A sustainable roadmap for financial investment is critically important. When you think about the adage: “Money makes the world go round”, effectively we’re talking about allocating capital in the right place when we're looking at sustainable development from a financial investment perspective. We need to allocate capital deliberately in a manner that achieves the most positive sustainability outcomes. We are referring to outcomes such as a green economy, decent jobs, and gender equality as examples. From a simplified peopleplanet-profit perspective, it’s effectively saying that businesses can’t survive in a society that is failing.

So a sustainable roadmap, from a financial investment point of view, fits into a broader notion of responsible investment and being able to be more responsible stewards for what we actually spend money on and invest in, and the impact that has on the environment and society.

What significant changes have you observed in the markets in relation to sustainability during your time at the JSE?

SS: There’s certainly been a tangible uptick in both awareness and the allocation of capital to responsible investment and responsible investment both the requirement for, and the interest in, credible institutions who can perform an external verification function – which is what the GBCSA does. This function brings credibility into the space and helps to mitigate the risk of greenwashing.

I have also seen an uptick in general societal awareness of sustainability-related matters – a growing acceptance that sustainability thinking is part of good governance – and increasing engagement by the investment community about bringing those considerations into investments.

What opposition have you come up against responsible investing ideas, during your time working at the JSE?

SS: In terms of sustainability, the past 15 years have seen a lot of changes in people’s thought processes. Some main oppositions have been that to be sustainable, you need to sacrifice return, and that there is always a significant upfront investment that doesn’t have an immediate monetary benefit. Another opposition is that there haven’t been regulations.

I have seen a common overarching narrative in sustainability that says: “If it’s not regulated, or there's no law or policy about it, then why should we do it? If it was important enough, there would be a law or a aims. Correspondingly, there has been an increase in

policy about it”. In the meanwhile, the shift to a more conscious capitalism is happening and in fact, there is mounting evidence that ESG funds and indices have been outperforming traditional market benchmarks. Using cost as the argument without real proper backing is something that is changing.

Why should we care about climate change when considering investing?

SS: The issues related to climate change are systemic in nature and have serious economic consequences. There is massive human impact in relation to exacerbating the challenges that we already have around poverty and inequality. The reality is that some of the world’s most vulnerable will be the worst hit by the impacts of climate change. Largely because their ability to adapt to those changes is almost non-existent.

When we consider that how we steward our money could either exacerbate or help mitigate some of the potential issues, then investing responsibly becomes more and more relevant. Investing in mitigation is showing to be more cost effective than having to bear the cost of the negative impacts of climate change in

the longer term. investing responsibly gives us the opportunity to try and lessen the future impact and costs – many of which we don’t even know. The reality is that some of the

How have behaviours and attitudes changed in the markets during Covid-19? How do you think Covid-19 will mould things going forward?

SS: There was a lot of volatility particularly during the early stages of lockdown in South Africa, but we have seen the market subsequently stabilised. Emerging markets often have a lesser ability to respond to crises which results in going into more debt to deal with the fallout, and the cycle continues. This means they enough to address those issues. If we really have learned anything from this, it is going to be, let’s tackle those gaps as a matter of urgency because the human impact is huge, and, as we have seen the costs to deal with crisis is staggering. It is the right thing

are often hardest hit. We’ve seen a significant decline in GDP as a country. But we were struggling before Covid-19. Going forward, I think we need to apply our minds to the “build back better” narrative.

What we’ve seen is that the inequalities in our society have been hugely exacerbated during this time. And it’s because historically we have not done a sum design process that

to do. The bottom line is that we need to invest in creating resilience.

What is the key takeaway you’d like people to gain from your keynote presentation?

SS: The evidence shows that investing responsibly doesn’t mean sacrificing returns.

THE UNPRECEDENTED DISPOSITION OF SUSTAINABILITY

PHILL MASHABANE Co-Founder, Mashabane Rose Architects, South Africa

What are your thoughts on developing a sustainable roadmap from a built environment as well as an

urban and cities’ perspective? PM: The articulation of the green building outcomes, actions, targets and policy development can enhance the desired intentions, only if the roadmap is simplified for the benefit of all members of society including those that question or may not realise the impact of green buildings ratings in response to the unprecedented global warming. The edges of the envelope are being stretched by technical developments that would need to be combatted by knowledge and application thereof. The founding principles of any design should show the embodiment of accommodating or responding to all possible opposing views and impacts thus leading to a sustainable solution.

What does regenerative design mean to you?

PM: Regenerative design represents a sum design process that encompasses all views including positive and non-positive to restore a common ground. This further revitalises all forms of energy and materials under consideration.

What are the founding principles that you believe each design should aspire to? Please use examples of your own work to illustrate this.

PM: The founding principles of any design should show the embodiment of accommodating or responding to all possible opposing views and impacts thus leading to a sustainable solution. This is exemplified in many of our projects wherein the client, the commissioned practitioner and the end user are considered, including various stakeholders who have a voice during design.

What kind of resistance have you come up against your design principles during your career, and how have you overcome it?

PM: The resistance we have come across, which of course gets ultimately resolved, is when a client or beneficiaries have preconceived outcomes of an undertaking. We have overcome this challenge by having extensive consultation with the relevant parties wherein we share a strategy that makes their desired outcomes realised. This process may take far too long, and threaten the viability of the project, but we’ll also recommend certain approaches and placements for the client, beneficiaries, and stakeholders.

What are the most significant changes you have seen in attitudes towards transformation and sustainable design over your career?

PM: The most significant changes in attitudes towards a transformative and sustainable design is the acceptance that most, if not all, matters need to be resolved or attended to at an early stage of concept development, no matter how long this process could be, even though this process could be time consuming with a risk of impeding on the timelines of the project.

How have behaviours and attitudes changed during Covid-19? How do you think Covid-19 will mould things going forward?

PM: Covid-19 has brought about varied behavioural and attitude changes to spaces and places that are meant for human beings. Covid-19 has successfully challenged any approaches that may have been deemed to be cast in stone. It has brought about an unassuming attitude for listenership.

How has technology influenced sustainable design?

PM: Technology evolves so rapidly that human attitude towards design solutions is also forced to adapt quickly. This has also created an opportunity for the designs to be adaptable and flexible to possible change.

What is the key takeaway you’d like people to gain from your keynote presentation?

PM: What I hope the audience will take away is that, until we learn and apply effective collaboration, and consideration of others, there will be nothing positive to offer future generations to come. Therefore, success is never achieved through singularity.

What are three takeaways you are personally hoping to get by attending and networking at convention?

PM: There are at least three takeaways that I hope for from this convention: 1. That humanity will learn to be considerate beyond financial gain. 2. That even the deemed to be insignificant voice should be heard for whatever it is worth. 3. That our voices are transformed into practical interventions to save planet earth.