8 minute read

TO BOLDLY GO

It may seem interesting to introduce this month’s page with the news that the Star Trek actor William Shatner, at the grand old age of 90, will at last ‘boldly go where no man has gone before’, as he heads into space, a passenger on a Blue Origin rocket.

Yet on the same day that this story broke, a slightly less media focused story was in the news, one that should have attracted the attention of all keen yachtsmen. On 17 September, a group of Scouts were aboard the Thames Barge, the Lady Daphne, as it passed under Tower Bridge to head off downstream to celebrate the centenary of the fi nal departure of Sir Ernest Shackleton, who was setting sail for the still uncharted waters of the Antarctic.

The real difference in the two stories, of course, is that 100 years ago, Shackleton really was ‘boldly going where no man had gone before’, as most of Antarctica was still waiting to be explored. However, if there was one man alive who knew the frozen continent

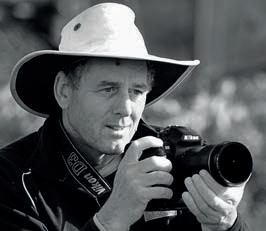

To Boldly Go… Whilst going into space is undoubtedly a bold adventure, daring quests have long been undertaken by brave explorers on our own seas and oceans. across all of the great oceans. The young Shackleton applied himself to the task of becoming an offi cer and, by the time he had reached his mid-20s, was already better than anyone else, it would have qualifi ed as a Master Mariner. to be Shackleton, a maverick traveller made in the same mould as other great Aboard Scott’s Expedition Victorian explorers. A chance meeting saw him seeking Ernest had been born in Ireland and out a berth on the National Antarctic throughout his life would remain proud Expedition that was being prepared in of his roots, but at an early age his family London, and in July 1901 he departed as moved to London. Despite a love for Third Offi cer aboard the Discovery, under the English romantic poets, Shackleton the leadership of Robert Falcon Scott. was not a great scholar and left formal Not only was Shackleton a popular schooling early in order to head out to sea. offi cer on the long voyage south, once With the family unable to afford the in Antarctica he would join Scott on a cost of taking up a cadetship with the further expedition across the ice, fi nally Royal Navy, he took the hard school reaching a latitude of 82° 17’ which, route, by shipping aboard a square- The chiselled features of Ernest Shackleton show a at that point, was the furthest south rigged cargo ship that would take him determination to succeed - and survive anyone had ever travelled. Their passage over the ice became fraught with diffi culties which would have a lasting effect on Shackleton’s health.

Once he had returned to public life after a period of convalescence, Shackleton’s long-standing aim, though he had numerous lines of employment, was to raise the fi nance needed for a second Antarctic expedition.

He would fi nally achieve this and in 1907 was back on the ice, where in another heroic feat of endurance he set a new record by getting to within 112 miles of the South Pole, with his route south including the fi rst ever ascent of the 3,800m high Mount Erebus.

Even though they failed to reach the South Pole, Shackleton was still feted as a hero on his return to London, which culminated in being knighted by King Edward VII. Plans for a further assault on the Pole were tempered by the news that Roald Amundsen had fi nally reached it on 14 December 1911, plus the tragedy that had befallen Scott’s own attempt.

BELOW: The 10 scouts who will be heading off to Antarctica line the rail as the Lady Daphne passes under Tower Bridge. What an incredible experience they will face during the opening days of 2022!

Thankfully today we can follow in the footsteps of Scott and Shackleton, gaining an understanding of the hardships that the crews experienced at the incredible Discovery Point Museum on Dundee’s waterfront. The centrepiece of the museum is the Royal Research Ship Discovery, which carried the brave men to the very bottom of the world and back. Image: Chris Lawrence Travel / Shutterstock.com

A New Goal Amazingly, in the same week that Great Britain declared war on Germany in 1914, Shackleton set sail once again, this time with a two ship expedition. Before departure Shackleton described their ultimate goal as “the last great object of Antarctic journeyings” that was left to him; the passage, on foot, across the continent from the Weddell Sea to the Ross Sea, via the Pole.

Once again, the severity of the weather conditions thwarted Shackleton’s plans, as the Endurance became trapped in the ice. This event had been planned for, with extra reinforcement - additional bracing for the hull - carried aboard, but even with this support the hull would still be crushed. The following spring, as the ice began to melt, the Endurance started to sink, leaving Shackleton and his men marooned on the remaining ice.

Eventually the crew, with their last supplies, reached land, but it would be far from salvation for them as they were now on Elephant Island, a lonely and inhospitable outcrop of land that offered them little chance of rescue. The nearest help was at the whaling station on South Georgia, but to reach that required a passage of more than 700 miles of the worst seas anywhere on the planet, and all Shackleton had at his disposal was an open 20ft long ship’s boat.

Rescue Mission Although Shackleton is rightly revered for his Antarctic expeditions, his seamanship in sailing the James Caird (named after the main sponsor of the expedition) northwards, through hurricane strength winds, must make this one of the most extraordinary passages at sea ever made.

Shackleton and the five crew members he took with him first raised the sheerline of their boat to give it more freeboard, then fabricated some decks to give a modicum of protection for the crew. It is almost impossible to even consider the hardships these men suffered, but in just 15 days the southern shores of South Georgia were finally sighted.

The conditions now were even worse than before and, rather than risk sailing on around the islands, Shackleton and some men set out on foot, with almost nothing in the way of supplies and equipment, to cross the steep terrain of South Georgia. Almost a month after leaving his trapped men on Elephant Island, they finally reached the Whaling station on the north coast and were able to raise the alarm, before getting a rescue mission sent out for the remainder of the crew.

Scouts on Board Five years later, after leaving London on 17 September, Shackleton would again be heading south, this time on the Quest, with his team on board including two young Scouts.

In early January 1922 the Quest would bring him once again to South Georgia, albeit under far more pleasant conditions. However, the years of hardship on the earlier expeditions had taken their toll on his health, plus it was later found that he suffered from congenital heart problems.

In the early hours of 5 January, Shackleton suffered a fatal heart attack and though moves were made to return his body to the UK for burial, Lady Shackleton decreed that her husband should be buried in South Georgia.

The ship’s doctor on the Quest, who had been with Shackleton at the end, said that the location for the grave was apt, with it “standing lonely in an island, far from civilisation, surrounded by stormy and tempestuous seas and in the vicinity of his greatest exploits”.

Shackleton’s death failed to capture the public spirit to the same extent that Scott’s had done, yet in so many ways his achievements can be seen as equalling those of his more famous friend (though in later years that friendship would become strained in the extreme).

As sailors, though, we should champion his memory for that extraordinary 720 mile voyage in an open boat, facing the worst that the Southern Ocean could throw at him.

Coming right back up-to-date, in December, 10 of the party of Scouts who helped celebrate the centenary of Quest’s departure will themselves be departing for their own expedition to Antarctica, a fitting tribute to a man who is surely one of the ‘greats’ of modern times.

We wish them well and look forward to hearing more of their adventure at the ‘bottom of the world’.

The bleak stone memorial that marks Shackleton’s grave in the Grytviken cemetery In South Georgia bears the simple inscription ‘Ernest Shackleton, Explorer’. Nothing more needs to be added, for that one word defines a man who went boldly where others had yet to go. Image: GTW / Shutterstock.com

A replica of the James Caird, the small boatthat Shackleton and his crew of five sailed over 720 miles to South Georgia to get help (that is from the Solent to the Fastnet and back to the Solent, in some of the worst seas and storms on the planet). Image: Michelle Sole / Shutterstock.com Shackleton and his crew ended up marooned on the desolate and inhospitable frozen wastes of Elephant Island. Far from any trade route, if they were to survive then the alarm would have to be raised - somehow! Image: Jo Crebbin / Shutterstock.com